The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 9, No. 3, March 4, 2013.

Japan’s Rightward Swing and the Tottori Prefecture Human Rights Ordinance

日本の右傾化と鳥取県人権条例

Arudou Debito

Japan’s swing to the right in the December 2012 Lower House election placed three-quarters of the seats in the hands of conservative parties. The result should come as no surprise. This political movement not only capitalized on a putative external threat generated by recent international territorial disputes (with China/Taiwan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and with South Korea over Takeshima/Dokdo islands). It also rode a xenophobic wave during the 2000s, strengthened by fringe opposition to reformers seeking to give non-Japanese more rights in Japanese politics and society.

This article traces the arc of that xenophobic trajectory by focusing on three significant events: The defeat in the mid-2000s of a national “Protection of Human Rights” bill (jinken yōgo hōan); Tottori Prefecture’s Human Rights Ordinance of 2005 that was passed on a local level and then rescinded; and the resounding defeat of proponents of local suffrage for non-citizens (gaikokujin sanseiken) between 2009-11. The article concludes that these developments have perpetuated the unconstitutional status quo of a nation with no laws against racial discrimination in Japan.

Keywords: Japan, human rights, Tottori, racial discrimination, suffrage, minorities, Japanese politics, elections, xenophobia, right wing

Introduction

As has been written elsewhere (cf. Arudou 2005; 2006a; 2006b et al.), Japan has no law in its Civil or Criminal Code specifically outlawing or punishing racial discrimination (jinshu sabetsu). With respect to the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (which Japan adopted in 1996), Japan has explicitly stated to the United Nations that it does not need such a law: “We do not recognize that the present situation of Japan is one in which discriminative acts cannot be effectively restrained by the existing legal system and in which explicit racial discriminative acts, which cannot be restrained by measures other than legislation, are conducted. Therefore, penalization of these acts is not considered necessary.” (MOFA 2001: 5.1)

However, in 2005, a regional government, Tottori Prefecture northwest of Ōsaka, did pass a local ordinance (jōrei) explicitly punishing inter alia discrimination by race. What happened to that law shortly afterwards provides a cautionary tale, demonstrating how public fear of granting any power to Non-Japanese occasioned the ordinance to be rescinded shortly afterwards. This article describes the defeat of a similar bill on a national scale, the public reaction to Tottori’s ordinance and the series of events that led to its withdrawal. The aftermath led to the stigmatization of any liberalization favoring more rights for Non-Japanese.

Prelude: The Protection of Human Rights Bill debates of the mid-2000s

Throughout the 2000s, there was a movement to enforce the exclusionary parameters of Japanese citizenship by further reinforcing the status quo disenfranchising non-citizens. For example, one proposal that would have enfranchised non-citizens by giving them more rights was the Protection of Human Rights Bill (jinken yōgo hōan). It was an amalgamation of several proposals (including the Foreign Residents’ Basic Law (gaikokujin jūmin kihon hō)) that would have protected the rights of residents regardless of nationality, ethnic status, or social origin.

According to interviews I conducted with proponents of the law in Japan’s human-rights communities (2000-5),1 the Basic Law had been drafted in 1998 after years of fractious debate among proponents. Rather than being submitted to the Diet as a bill (chinjō or hōan), it was submitted as a “petition” (seigan) for consideration. The more comprehensive Human Rights Bill (which did not focus specifically on non-citizen protections against discrimination, and established clear oversight committees and a criminal-penalty structure) was submitted in 2002 by the first Koizumi Cabinet, but died in committee in October 2003 with the dissolution of the Upper House. When talk was raised of resubmission, it was shouted down by arguments opposing giving Zainichi Koreans, particularly those affiliated with North Korea, any political power; the proposal had been ill-timed, in light of the political capital being gained by rightists during a 2002-6 debate concerning geopolitical stances towards the rachi mondai (i.e., North Korean kidnappings of Japanese that had reportedly occurred between 1977-83). The Bill remains in limbo, with a different incarnation (the Human Rights Relief Bill, jinken kyūsai hōan) wending its way through committees as of this writing.2

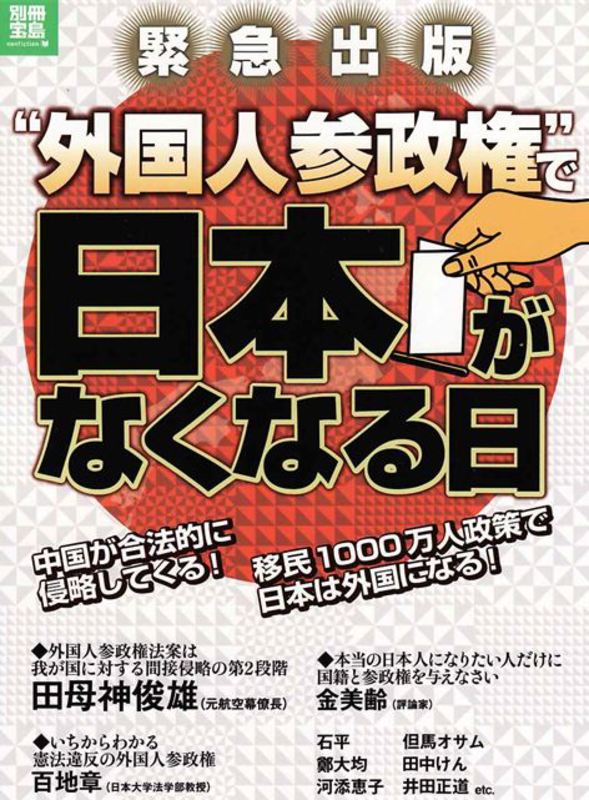

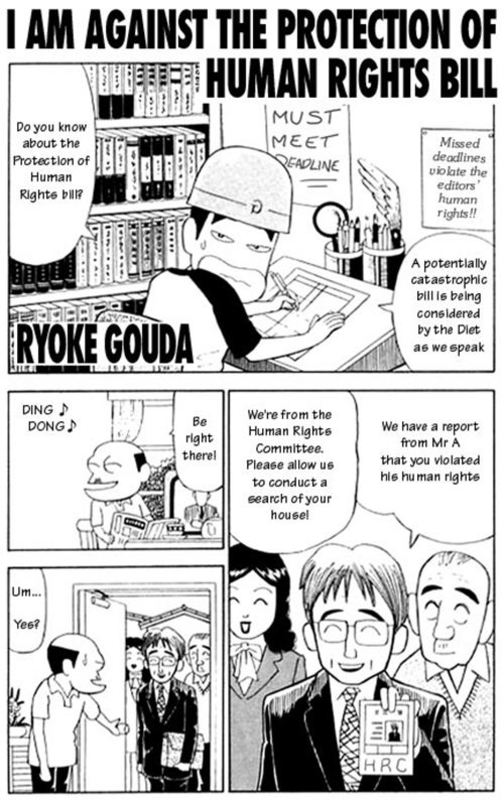

Germane to this research is the xenophobic discourse behind the defeat of this Bill. Consider one prominent book by a fringe publisher found on bookshelves nationwide that featured famous authors (including an outspoken Dietmember and a well-known journalist) opposing it:

Front and back cover of Danger! The Protection of Human Rights Bill: The Imminent Threat of the Totalitarianism (zentai shugi) of the Developed Countries (Tendensha Inc., April 28, 2006.). Note the connections being made in the top left corner between this Bill and the Foreigner Suffrage issue (see below): gender equality, the rights of children, the North Korean kidnappings, the treatment of history in educational textbooks, and patriotic visits to Yasukuni Shrine – all divisive issues of the day between rightists and leftists in Japanese politics. The back cover features prominent rightist spokespeople Member of Parliament (MP) Hiranuma Takeo and journalist Sakurai Yoshiko. Tendensha Inc.’s rudimentary website may be found at here. Within this book was an excellent manga that made the opposition’s arguments clearly (NB: Translated into English for the reader’s convenience by Miki Kaoru, original Japanese version archived here): |

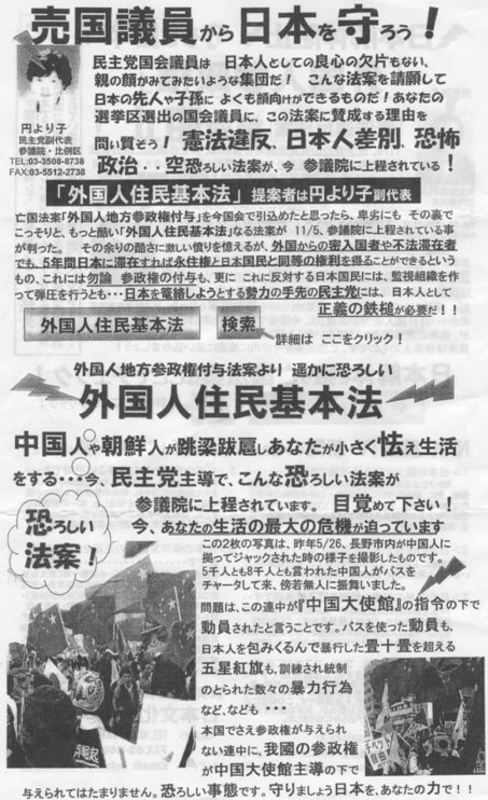

|

|

|

|

The Danger! book, pp. 37-39. Note the racialized allegations of abuses of power, where darker-skinned or narrower-eyed “foreigners” would become lazy, delinquent, or disobedient towards social contracts if granted any rights. Moreover, this law would also lead to abuses between Japanese in terms of personal revenge or crime-syndicate blackmail. The assumption is that members of the Human Rights Committee (as opposed to the existing system of Human Rights Protection Officers footnoted on page 37 of the Danger! book) would not investigate the validity of claims beforehand. Remaining unproblematized is the efficacy of people in positions of power (e.g., employer, renter, teacher, or business owner) retaining and enforcing their prejudices towards women and “foreigners.” As can be seen below, this claim of reverse discrimination and “victimization” of the discriminator is a common meme within counterarguments to liberalization proposals favorable to minorities in Japan.) |

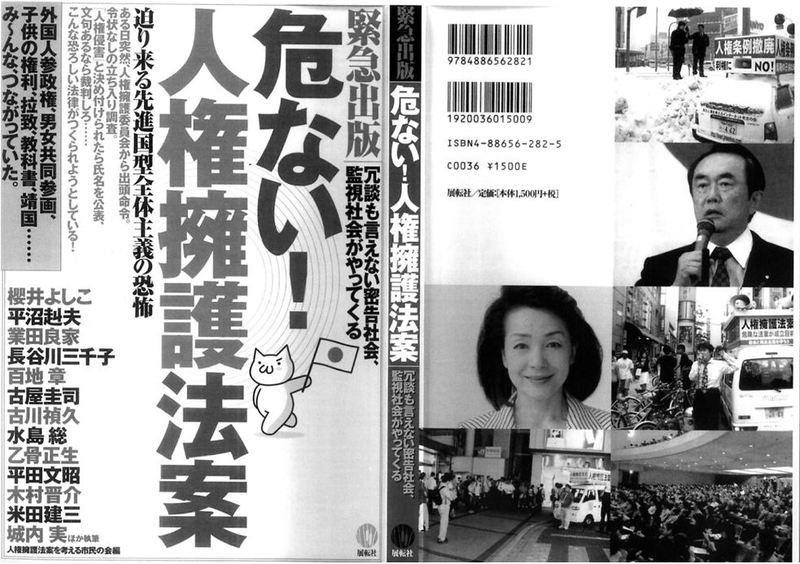

|

|

|

|

The Danger! book, pp. 143-45. This focuses on the potential official abuses of enforcement, where a person in a position of power is being victimized: being taken advantage of (as a landlord) by “Asian foreigners”, being caught in the pugilistic crossfire (as a business owner) of a violent racist “Western foreigner,” or being singled out in a crowd while exercising his right of public protest. The alarmism camouflaged by this absurdist humor neglects to mention that, a) no particular charge has been leveled against the victimized person; if this manga showed National Police Agency officers potentially doing the same thing, it would become an argument against any police forces – clearly a reductio ad absurdum; and, b) if anyone does something unlawful (such as violate a residential contract or cause a public disturbance), would it not be prudent for the person being victimized above to report it to the police (as a countermeasure to any perpetrator possibly cloaking his illegal activities as an extension of his “human rights”)? The assumption again is that the new Human Rights Committee will not be able to screen out nuisance cases from bona fide cases – again, an argument that could be made against any policing agency.) |

The thrust of these arguments is that changing the status quo to grant rights to people who were previously not in a position of power will necessarily result in those people abusing their newfound power and causing social disorder. In other words, if somebody does something that somebody else personally does not like, it will become a legitimate claim of a violation of human rights. Unproblematized, however, are the normalized and unchecked abuses of majoritarian power that are being defended and justified within this manga (as in the abovementioned underlying prejudices against and intolerance towards women and “foreigners”), not to mention the racialized and stereotyped prejudices of the author towards minorities in Japan.

Nevertheless, these arguments were made concisely and powerfully in a well-organized media campaign that stressed unassailable tropes such as freedom of speech and of the press (which allegedly were under attack by the Bill’s allegedly “vague” (aimai) definitions of “human rights”), grounded in an undercurrent of fear for Japan’s national integrity in the face of looming external threats (particularly North Korea). They were sufficient to defeat the Protection of Human Rights Bill. Similar fear-based counterarguments were also one reason why Japan had not hitherto succeeded in passing legislation against racial discrimination, and when a measure was passed at the local level – in Tottori Prefecture – a similar campaign arose to defeat it.

Tottori Prefecture’s Human Rights Ordinance

On October 12, 2005, after nearly a year of deliberations and amendments, the Tottori Prefectural Assembly approved a human rights ordinance (tottori-ken jinken shingai kyūsai suishin oyobi tetsuzuki ni kansuru jōrei) that would not only financially penalize eight types of human rights violations (including physical abuse, sexual harassment, slander, and discrimination by “race” – including “blood race, ethnicity, creed, gender, social standing, family status, disability, illness, and sexual orientation”), but also set up an investigative panel for deliberations and provide for public exposure of offenders.3 Going farther than the already-existing Ministry of Justice, Bureau of Human Rights (jinken yōgobu, which has no policing or punitive powers), it could launch investigations, require hearings and written explanations, issue private warnings (making them public if they went ignored), demand compensation for victims, remand cases to the courts, and even recommend cases to prosecutors if they thought there was a crime involved. It also had punitive powers, including fines up to 50,000 yen. Sponsored by Tottori Governor Katayama Yoshihiro, an advocate not just of human rights legislation but also of decentralized government,4 it was to be a trial measure – taking effect on June 1, 2006 and expiring on March 31, 2010. The carefully-planned ordinance was created by a committee of 26 people over the course of two years, with input from a lawyer, several academics and human rights activists, and three non-citizen residents. It passed the Tottori Prefectural Assembly by a wide margin: 35 votes to 3.

However, the counterattack was immediate.5 The major local newspaper in the neighboring prefecture, the Chūgoku Shimbun (Hiroshima), claimed two days later in an October 14 editorial entitled, “We must monitor this ordinance in practice,” that the ordinance would “in fact shackle (sokubaku) human rights.” Accusations flew that assemblypersons had not read the bill properly, or had supported abstract ideals without thinking them through. Others said the governor had not explained to the people properly what he was binding them to. Internet petitions blossomed to kill the bill. Some sample complaints (with my counterarguments in parenthesis, for brevity): a) The ordinance had only been deliberated upon in the Assembly for a week (though it was first brought up in 2002 and had been discussed in committees throughout 2005); b) The ordinance’s definitions of human rights violations were too vague, and could hinder the media in, for example, investigating politicians for corruption (even though the ordinance’s Clause 31 clearly states that freedom of the press must be respected); c) Since the investigative committee was not an independent body, reporting only to the governor, this could encourage arbitrary decisions and cover-ups (similar to the existing Bureau of Human Rights, which reports only to the secretive Ministry of Justice6); d) This invests judicial and policing powers in an administrative organ, a violation of the separation of powers (which means that no oversight committee in Japan is allowed to have enforcement power – but this calls into question many other ordinances in Japan, such as those governing garbage disposal, that mandate fines and incarceration).

The Japan Federation of Bar Associations (Nichibenren) sounded the ordinance’s death knell in its official statement of November 2, 2005: Too much power had been given the governor, constricting the people and media under arbitrary guidelines, under a committee chief who could investigate by diktat, overseeing a bureaucracy that could refuse to be investigated. This called into question the policymaking discretion of the committees that had originally drafted it, and the common sense of the 35 prefectural assembly members who overwhelmingly passed it. The government issued an official Q&A to allay public concern, and the Governor said problems would be dealt with as they arose, but the original supporters of the ordinance, feeling the media-sponsored and internet-fomented pressure, did not stand up to defend it. In December and January 2006, the prefecture convened informal discussion groups containing the vice-governor, two court counselors, four academics, and five lawyers (but no human rights activists). In addition to other arguments used to rescind the bill, critics now wondered how un-appointed untrained public administrators ostensibly could act as judges.

On March 24, 2006, less than six months after passing the ordinance, the Tottori Prefectural Assembly voted unanimously to suspend it indefinitely. “We should have brought up cases to illustrate specific human rights violations. The public did not seem to understand what we were trying to prevent,” said Mr. Ishiba, a representative of the Tottori Governor’s office.7 “They should have held town meetings to raise awareness about what discrimination is, and created separate ordinances for each type of discrimination,” said Assemblywoman Ozaki Kaoru, who voted against the bill both times.8 Governor Katayama resigned his governorship in April 2007, saying that ten years in office was enough.9 The ordinance was later resubmitted to committees in 2007, where it was voted down for the last time.10 As of this writing, the text of the ordinance, Japan’s first legislation explicitly penalizing racial discrimination, has been removed from the main Tottori Prefectural website and buried within a new link.11 It effectively remains preserved in amber as Japan’s only successful legislation against racial discrimination.

The aftermath: An emboldened xenophobia within Japan’s right wing12

When the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) took power from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in 2009, one of their liberalizing party platforms was granting non-citizen Permanent Residents (ippan eijūsha and tokubetsu eijūsha) the right to vote in local elections (Foreigner Suffrage, or gaikokujin sanseiken), in part because non-citizens, particularly the Zainichi Special Permanent Residents, had historically spent their lives born in, living in and contributing to Japan; moreover, they already had the vote on local referendums in some municipalities. Politically the proposal seemed advantageous to the DPJ at the time it was first proposed in 2008 (when the DPJ was the opposition party (yatō)), as it threatened to split the then ruling coalition by tempting away LDP partner Kōmeitō (a religious-based party founded by the Sōka Gakkai, which initially supported the proposal due to the group’s international following).13 A common counterargument to Foreigner Suffrage was, “If non-citizens want to vote, they should naturalize.” However, as seen in opponents’ arguments, there were cases of non-Japanese roots despite Japanese citizenship being problematized (including public statements by prominent elected officials like MP Hiranuma and Tōkyō Governor Ishihara Shintarō questioning the loyalties of political opponents due to their “mixed blood” or alleged “foreign roots,” rather than any logical or legal basis), mooting the efficacy of naturalization as an alternative.14

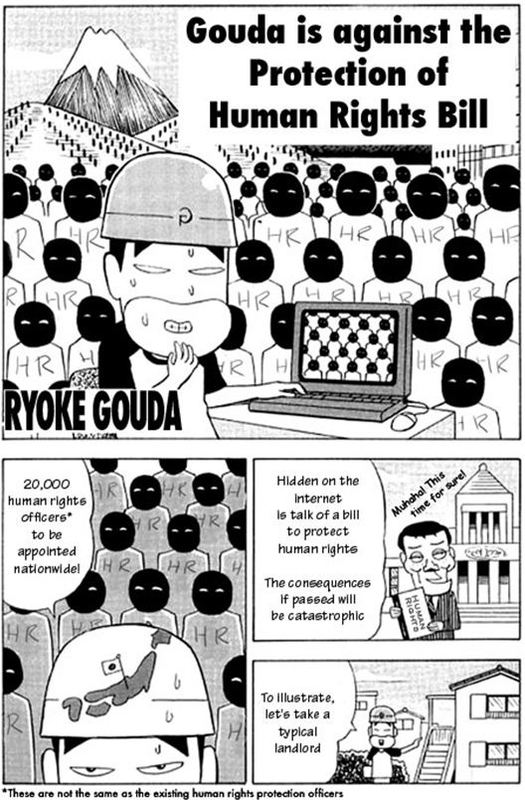

Further, Japanese representatives both outside and within the DPJ, not to mention fringe-rightist elements within Japanese politics, found the sanseiken proposal a convenient means to decry external and internal “foreign” influences over Japanese society. As can be seen below, public fears were stoked by frequent public meetings, demonstrations, and billeting that argued that granting any more rights to non-citizens would be “the end of Japan,” with alarmist invective including North-Korean or Chinese-controlled representatives being elected to Japanese office, secessions of parts of Japan to China and South Korea, and even alien invasion:

Note that it is not a large leap from the officially-sponsored imagery and invective involving invasions of Japan by “foreign criminals” to imagery of invasion and subversion of Japan through the electoral process. There was even formal linkage made to it within the debate:

In order to gain leverage against the fledgling DPJ Hatoyama Administration (see other rightist protest flyers archived here and here), rightist elements made formal linkages with other DPJ proposals that would have protected the rights of non-citizens, such as the aforementioned Foreign Residents Basic Law (which by then was a moribund Bill):

Even though proponents (including the Asahi Shimbun of July 6, 2010, citing an opinion poll of 49% of respondents in favor of non-citizen suffrage and 43% against) took a stand, the lack of a minority opposition voice (not to mention their political disenfranchisement), media access, and the inability to choose sympathetic political representatives – a vicious circle), plus a DPJ already deeply-divided over the Foreign Suffrage Bill, allowed it to be shouted down. The DPJ formally “postponed” the bill by February 2010, and dropped it from the DPJ Manifesto entirely by the July 11, 2011 Upper House Elections.15

However, the reactionary social movement that had crystallized around this bill maintained its momentum: The protests against “foreign rights” were then leveraged as a template into successful protests against other DPJ rights-based liberalizing measures, such as separate surnames for married couples (fūfu bessei) (which LDP head Tanigaki Sadakazu claimed, in similar now-normalized apocalyptic invective, “would destroy the country”).16 Even after the DPJ had dropped the foreigner suffrage proposal, the issue was raised repeatedly in public demonstrations, with an anti-suffrage rally on April 17, 2010 in the Budōkan (organized by Sassa Atsuyuki, the former Secretary General of the Security Council of Japan) attracting a reported 10,257 attendees.17 Rightist grassroots activists also successfully pushed several local and prefectural assemblies nationwide to pass formal resolutions in opposition to it.18

Meanwhile, nationalistic and xenophobic media used the attention garnered by this movement to create a self-sustaining media presence,19 legitimized by prominent politicians/pundits (such as former – and now current – PM Abe Shinzō, MP Hiranuma Takeo, MP Kamei Shizuka, former Air Self-Defense Forces Chief of Staff General Tamogami Toshio) basking in the attention. Thus, by the end of the 2000s, “foreigners” in Japan had become a political football within a whirlwind of time, money, organization, and energy devoted to nationalistic, xenophobic, and exclusionary causes20 (including, of course, geopolitical disputes over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands with China/Taiwan, and the Takeshima/Dokdo Islands with South Korea, leading to xenophobic rallies within Japan’s ethnic neighborhoods, and the resignation of Tōkyō Governor Ishihara to prepare for reelection to national office).21

Conclusion

The normalization of racialized and exclusionary invective in Japanese politics has enabled political language to shift perceptibly into xenophobia, with claims of widespread “foreign crime” (Arudou 2007) being connected with contemporary domestic and geopolitical issues to justify an enforced political disenfranchisement of minorities in Japan. As political discourse focused upon “foreign” issues, invective turned from exclusionary to apocalyptic, mutating isolated cases of a few Japanese victims of crime into an image of Japan as a nation under siege from the outside world. One underlying argument has been, in effect, “more foreigners means less Japan,” making any form of compromise (such as granting liberalized rights protections not only to foreigners, but also to multiethnic Japanese citizens) impossible without Japan “coming to an end.” In the rightist media, proponents began looking for issues upon which to hang and propel a conservative and exclusionary agenda. This has caused rights-oriented reforms and legislation not only to be shelved, but also abrogated, which to some degree explains why a perpetually-disenfranchised minority in Japan will find it difficult, despite constitutional guarantees, to garner sufficient public support behind protecting non-Japanese from discriminatory language and behavior.

In fact, in 2012, when this wave of xenophobia crested into a mainstream territorial dispute with China/Taiwan and South Korea, any policymaking legacy supporting “foreigner” issues became part of a poisonous invective that contributed to the resounding defeat of the DPJ in December 2012. Given this political climate, any public support for universal “human rights issues” in Japan will remain political poison for any legislator as long as there is any alleged benefit to “foreigners.” Japan’s formerly exclusionary, now xenophobic, status quo will hold for the foreseeable future.

Arudou Debito is a writer, activist, blogger (www.debito.org), and columnist for the Japan Times. He is the author of Japanese Only, the Otaru Hot Springs Case and Racial Discrimination in Japan (Akashi Shoten, English and Japanese), and coauthor, with Higuchi Akira, an administrative solicitor in Sapporo who also is qualified as an immigration lawyer by Sapporo Immigration, of the bilingual Handbook for Newcomers, Migrants and Immigrants to Japan (2nd edition). Find more details on the book and other books by Arudou here.

Recommended Citation: Arudou Debito, “Japan’s Rightward Swing and the Tottori Prefecture Human Rights Ordinance,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 9, No. 3, March 4, 2013.

Articles on related subjects

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Freedom of Hate Speech; Abe Shinzo and Japan’s Public Sphere

•Narusawa Muneo, Abe Shinzo, a Far-Right Denier of History

• Gavan McCormack, Abe Days Are Here Again: Japan in the World

• Okano Yayo, Toward Resolution of the Comfort Women Issue—The 1000th Wednesday Protest in Seoul and Japanese Intransigence

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Out With Human Rights, In With Government-Authored History: The Comfort Women and the Hashimoto Prescription for a ‘New Japan’

• Lawrence Repeta with an introduction by Glenda Roberts, Immigrants or Temporary Workers? A Visionary Call for a “Japanese-style Immigration Nation”

• Yoshiko Nozaki and Mark Selden, Japanese Textbook Controversies, Nationalism, and Historical Memory: Intra- and Inter-national Conflicts

• Arudou Debito and Higuchi Akira, Handbook for Newcomers, Migrants, and Immigrants to Japan

• Wada Haruki, The Comfort Women, the Asian Women’s Fund and the Digital Museum

• Arudou Debito, Japan’s Future as an International, Multicultural Society: From Migrants to Immigrants

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki “Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’: It’s time for the truth (in the ordinary, everyday sense of the word)”

• Arudou Debito, The Coming Internationalization: Can Japan assimilate its immigrants?

• Rumiko Nishino “The Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace: Its Role in Public Education”

References

Arudou, Debito. 2005. “‘Gaikokujin’ Nyūten Kinshi to iu Jinshu Sabetsu” [“‘Foreigners’ Excluded from the Premises” as Racial Discrimination], in Okamoto Masataka, Ed., Nihon no Minzoku Sabetsu: Jinshu Sabetsu Teppai Jōyaku kara Mita Kadai, [Japan’s Ethnic Discrimination: Topics from the view of the UN CERD], pp. 218-29. Tōkyō: Akashi Shoten.

Arudou, Debito. 2006a. Japanīzu Onrī: Otaru Onsen Nyūyoku Kyohi Mondai to Jinshu Sabetsu. 2nd ed. Tōkyō: Akashi Shoten.

Arudou, Debito. 2006b. Japanese Only: The Otaru Hot Springs Case and Racial Discrimination in Japan. 2nd ed. Tōkyō: Akashi Shoten.

Arudou, Debito. 2007. “Gaijin Hanzai Magazine and Hate Speech in Japan: The newfound power of Japan’s international residents.” Japan Focus, March 20.

Kaihō Shimbun. 2005. “‘Jinken Shingai Kyūsai Jōrei’ o seitei: Zenkoku de hajimete Tottori Ken de” [Establish a human rights ordinance: Tottori to be the first in Japan]. October 24, available online here. (accessed January 24, 2013).

Keiō University. 2012. “Keio in Depth: Research Frontier: Interview with Yoshihiro Katayama, Professor, Faculty of Law.” Translation of article in Kenkyū Seisenzen by Keiō University, dated January 16, 2012. Available online here. (accessed January 24, 2013).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2001. “Comments of the Japanese Government on the Concluding Observations adopted by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination”. October.

Sakurai, Yoshiko et al. 2006. Kinkyū Shuppan: Abunai! Jinken Yōgo Hōan: Semari kuru Senshinkoku Kei Zentai Shugi no Kyōfu [Urgent Publication: Danger! The Protection of Human Rights Bill: The Imminent Threat of the Totalitarianism of the Developed Countries]. Tōkyō: Tendensha.

Tamogami, Toshio et al. 2010. Kinkyū Shuppan: “Gaikokujin Sanseiken” de Nihon ga Nakunaru Hi Urgent Publication: Doomsday for Japan due to Foreign Suffrage]. Tōkyō: Bessetsu Takarajima.

Tanaka, Hiroshi. 2006. In Kim Geduk, ed. Nichi/Kan “Kyōsei Shakai” no Tenbō [A view to a Japanese/Korean “Coexistence Society”]. Tōkyō: Shakansha.

1 See for example the Gaikiren (now Gaikikyō) group website on these subjects at http://gaikikyo.jp. This Catholic group was the main proponent of the Bill until the events that transpired in the next section.

2 See for example “Minshu bumon kaigi, jinken kyūsai hōan o ryōshō; hantaiha no iken oshi kiri.” Sankei Shimbun, August 29, 2012.

3 See “Tottori rights law a first but irks critics.” Japan Times, October 13, 2005. See the text of the ordinance (from a dead-link archive).

4 Why did Gov. Katayama make such a bold move to establish Japan’s first comprehensive human rights ordinance? Part of the reason is due to his background: A graduate of Tōkyō’s elite Faculty of Law, Katayama had a steady rise first as a bureaucrat in the Ministry of Home Affairs, then other posts including an administrator in the National Tax Office, Secretary to the Minister of Home Affairs, and head of the Tottori Prefecture General Affairs Department, before becoming Tottori Governor in 1999 and being re-elected in 2003. According to an interview (Keiō University, 2012), Katayama is a firm believer in decentralized local governance and, after first floating the idea of a local human-rights ordinance in June 2002, probably felt that his re-election provided a mandate to achieve “real democratic local government” through a landmark human-rights ordinance. (He also stated in 2005 that leaving the creation of human rights laws to the Ministry of Justice alone was not a good idea, and that local governments should also work in conjunction with the national Protection of Human Rights Bill mentioned in the previous section (Kaihō Shimbun, 2005)). Indicatively, Katayama’s ordinance is never mentioned in the Keiō interview. After its repeal, Katayama did not run for reelection, but after a break went on to become Cabinet Minister of Internal Affairs and Communications 2010-1 under the Kan Administration, and is currently a professor of law at Keiō University.

5 Adapted from Arudou, “How to kill a bill: Tottori’s Human Rights Ordinance is a case study in alarmism.” Japan Times, May 2, 2006.

6 See “Watching the detectives: Japan’s human rights bureau falls woefully short of meeting its own job specifications.” Japan Times, July 8, 2003.

7 Phone interview, Tottori Prefecture Governor’s Office, April 25, 2006.

8 Phone interview, April 25, 2006.

9 See “Katayama chiji ga sansen fushutsuba hyōmei.” San-in Chūō Shimbun, December 26, 2006.

12 A thoughtful overview of this debate may be found in “Disenfranchised: Japan weighs up whether to give foreign residents the vote.” Metropolis Magazine, June 17, 2010.

13 See inter alia “Komeito leader welcomes Ozawa’s proposal to give foreigners voting rights.” Mainichi Shimbun, January 24, 2008; “Minshuto to push foreign suffrage.” Asahi Shimbun, January 25, 2008; “DPJ holds opposing meetings on foreigners voting in local elections.” Kyodo News, January 31, 2008, which notes that there was allegedly a feeling of international movement in support of suffrage liberalization, reporting: “The South Korean government has repeatedly called on Japan to allow permanent residents of Korean descent, who make up the bulk of foreign residents in Japan, to vote in local elections. South Korea allowed foreigners who have lived in the country for more than three years after obtaining permanent residency to vote in local elections for the first time in June 2006.” See also “FYI: Suffrage; Expats won hard-fought battle but suffrage still eludes foreign permanent residents.” Japan Times, June 3, 2008; Tanaka (2006: 76-7), translated here, with a list of 25 other developed countries that allow permanent resident non-citizens to vote under certain circumstances, showing Japan as the absolutist outlier.

14 See “Gaikokujin sanseiken ‘Senzo e giridate ka: Ishihara chiji ga yoto hihan.” Asahi Shimbun, April 18, 2010; “Tokyo governor calls ruing party veterans ‘naturalized’.” AP, April 19, 2010; “Fukushima shamin tōshu ga Ishihara tochiji no hatsugen no tekkai motomeru.” Sankei Shimbun, April 19, 2010; “Natural born voters?” The Diplomat, April 20, 2010; “Ishihara snubs SDP retraction request.” Japan Times, April 24, 2010. See also “’Motomoto nihonjin ja nai:’ Hiranuma shi ga Renhō shi o hihan.” Sankei Shimbun, January 18, 2010; “Ex-minister Hiranuma says lawmaker Renho is ‘not originally Japanese’.” Kyodo News, January 18, 2010; “Non-Japanese suffrage and the racist element.” Japan Times, February 2, 2010. On a related note, Hiranuma has a history of xenophobic, not to mention misogynistic, statements. On February 1, 2006, he stated that Emperors should only be male because females might marry a “foreigner:” “If [Princess] Aiko becomes the reigning empress and gets involved with a blue-eyed foreigner while studying abroad and marries him, their child may be the emperor. We should never let that happen.” Why females are innately more susceptible to the seductive wiles of “foreigners” than males are was left unclear. See “Female on throne could marry foreigner, Hiranuma warns.” AP, February 2, 2006.

15 See “DPJ holds opposing meetings on foreigners voting in local elections.” Kyodo News, January 31, 2008; “Parties split on foreigner suffrage.” Japan Times, August 18, 2009; “DPJ postpones bill to grant local voting rights to permanent foreign residents.” Mainichi Shimbun, February 27, 2010; “Editorial: Foreigners’ voting rights.” Asahi Shimbun, July 6, 2010. As they poignantly argued, in excerpt (official translation), “Some say foreigner suffrage goes ‘against the Constitution.’ However, it is only natural to construe from the Supreme Court ruling of February 1995 that the Constitution neither guarantees nor prohibits foreigner suffrage but rather ‘allows’ it. The decision on foreign suffrage depends on legislative policy. In an age when people easily cross national borders, what kind of society does Japan wish to become? How do we determine the qualifications and rights of people who comprise our country and communities? To what extent do we want to open our gates to immigrants? How do we control social diversity and turn it into energy?” In a counter editorial, the Yomiuri argued in October 2009: “It is not unfathomable that permanent foreign residents who are nationals of countries hostile to Japan could disrupt or undermine local governments’ cooperation with the central government by wielding influence through voting in local elections.” (ibid, Metropolis Magazine, June 17, 2010)

16 See “Foreigner suffrage, separate surnames stir passions in poll run-up.” Japan Times, July 3, 2010. “Japan split over maiden names, foreign suffrage.” Kyodo News, July 9, 2010.

17 Archive of further protests and flyers here. See also “Foreigner suffrage opponents rally: Conservative politicians express outrage at DPJ plan.” Japan Times, April 18, 2010; “Lawmakers oppose giving foreign residents right to vote.” Kyodo News, April 18, 2010.

18 See inter alia “14 prefectures oppose allowing foreigners to vote in local elections.” Kyodo News, February 9, 2010; this includes eight prefectures that once supported the measure, but changed their stance under pressure;“8 ken gikai ga ‘hantai’ ni tenkō.” Mainichi Shimbun, February 9, 2010. See also template opposition resolution “Eijū gaikokujin e no chihō sanseiken fuyo no hōseika ni hantai suru ikensho (an),” passed by Tsukuba City Assembly December 2010, archived here, courtesy of Tsukuba City Councilor Jon Heese.

19 See for example very active Internet channel Nihonbunka Chaneru Sakura. When last accessed in July 2012, a very prominent interview with current PM Abe was featured.

20 See inter alia Cabinetmember Kamei Shizuka’s xenophobic comments as Financial Services Minister in “Foreigner suffrage can fuel nationalism: Kamei.” Japan Times, Feb. 4, 2010; “New dissent in Japan is loudly anti-foreign.” New York Times, August 28, 2010; “A black sun rises in a declining Japan.” Globe and Mail (Canada), October 5, 2010; “Japan: The land of the rising nationalism.” The Independent (London), November 5, 2010.

21 See for example “Nationalists converge on Shin-Okubo’s Koreatown.” Japan Today.com, September 17, 2012. It reports that there have also been threats of violence towards Zainichi minority shopkeeps, citing Shūkan Kin’yōbi Magazine: “’It appears that the Zaitokukai (short for Zainichi Tokken wo Yurusanai Shimin no Kai or group opposed to special rights for Koreans in Japan) thinks it can build momentum for its movement by harping on the Takeshima and Senkaku issues,’ says journalist Yasuda Koichi, who authored a book titled ‘Pursuing the darkness of Internet patriots, the Zaitokukai’ (Kodansha), about the noisy group that has been boosting its membership through skillful use of the Internet. ‘While I don’t see any signs yet that they are increasing their influence, they still bear watching,’ Yasuda comments. ‘As far as they are concerned, discriminating against the zainichi (Koreans in Japan) is everything, and they aren’t terribly concerned about what will become of the disputed territories in the future. But they can use the timing of the dispute as a pretext for pushing their own agenda.’”