Cambodian King Norodom Sihanouk was cremated on the fourth of February at the Meru field next to the royal palace in the capital, Phnom Penh. His embalmed body had been lying in state since he died of a heart attack in Beijing on 15 October 2012 at the age of 89. Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians, most of whom have not known life without the charismatic monarch in one capacity or another flocked to Phnom Penh, to pay their last respects as Sihanouk was given elaborate funeral rites on a scale not seen since the death of his father King Suramarit 53 years ago. With the passing of Sihanouk and decline in the significance of monarchy we will probably never see such elaborate funeral rites again in Cambodia.

Chariot carrying King Sihanouk’s gilded coffin being paraded in phnom Penh street, Friday, February 1, 2013. |

On 4 February the people witnessed the elaborate cremation in an outpouring of national mourning for the “King-Father”. After sundown, in religious ceremonies led by chanting monks, Sihanouk’s tearful widow Queen Monineath and son King Norodom Sihamoni both clad in white entered the inner chamber of the elabor $5 million 47 meter high fifteen story pagoda built specifically for the occasion and illuminated with thousands of tiny lights. King Sihamoni symbolically lit hhis father’s sandalwood oil-soaked body and smoke was seen rising into the sky from the crematory. It will be dismantled later in keeping with Cambodian tradition. A 101-gun salute echoed through the night and fireworks burst over the city.

The pyre being lit to cremate King Siihanouk body while fireworks lit up the sky. February 4, 2013. |

Prime Minister Hun Sen, who today holds all executive power, declared a seven day period of mourning from 1 to 7 February as a last tribute to the King father. After the cremation, some of Sihanouk’s ashes will be scattered where the Mekong, Tonle Sap and Tonle Bassac rivers meet. The remainder will be taken to the royal palace where they will be kept in a royal urn in accordance with the former king’s wishes. Political commentators believe that the elaborate cremation ceremonies were Hun Sen’s way of paying tribute to the king’s legacy as the father of the modern nation who led the campaign for independence from France until his overthrow in 1970 by a rightwing general.

Born in Phnom Penh on October 31, 1922, and crowned king by Cambodia’s French colonial rulerss in 1941, Sihanouk played a role in the country’s politics for over seven decades, variously as monarch, prince, head of state, prime minister, head of the Khmer Rouge government, chairman of the post-civil war coalition government, head of the Supreme National Council, and again as constitutional monarch from 1993 until he abdicated in 2004.

The list of dozens of foreign dignitaries who came for the cremation included those representing countries with special relations with the king and with Cambodia. They include senior Chinese official Jia Qinglin, Chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and former high ranking politburo member, French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault, Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung, Thai Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, Laos Prime Minister Thongsing Thammavong, Vice President of the Philippines Jejomar C. Binay, and Japanese Prince Akishino, brother of the crown price, as well as others from India and neighboring countries. According to a government statement, Jia Qinglin, Jean-Marc Ayrault and Prince Akishino were received in separate royal audience by Cambodian King Norodom Sihamoni and Queen-Mother Norodom Monineath at the Royal Palace.

The Chinese of course held a special relationship with King Sihanouk over many years. He spent a great deal of time in Beijing for medical treatment and, as will be shown below, in political exile in the 1970s and the 1980s. Today China has strong ties with the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen and is the largest donor to and investor in Cambodia.

The French crowned Sihanouk King in 1941 under their protectorate but he managed to gain independence from them in 1953. In the 1980s and 1990s France was important as the co-convener, with Indonesia, of the Paris Agreements which solved the political impasse of the 1980s in Cambodia. After the establishment of the new Royal Government of Cambodia in 1993, France. alternating with Japan, hosted the annual coordination meetings on foreign aid to Cambodia. Japan also played an important role as the major donor for years after the elections held by the United Nations in 1993.

The leaders from neighboring fellow ASEAN countries showed their solidarity with Cambodia as ASEAN is becoming increasingly important as a regional economic and political entity. Special mention should be made of the presence of Thai premier Yingluck Shinawatra, sister of exiled former prime minister Taksin Shinawatra, who is a close friend of Hun Sen. Taksin is the leader of the populist red shirts who battled the royalist yellow shirts for years. The King of Thailand has always been close to Sihanouk and his Royalist politicians long received protection in Thailand. Hun Sen gave a special audience to his Thai counterpart.

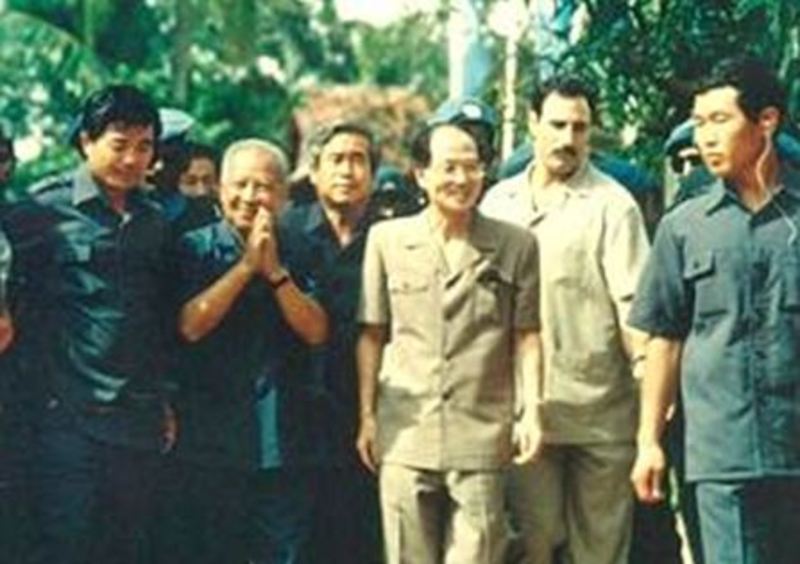

Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia welcomed back Prince Sihanouk in November 1991 from twelve years of exile as Head of the CGDK controlling border refugee camps. |

Conspicuously, the US was represented by their relatively low key ambassador in Phnom Penh, William E. Todd, raising questions given the long U.S. involvement in Cambodia. As will be shown below, during the turbulent period of civil wars in the 1960s and 1970s Sihanouk had a tempestuous relationship with the United States. Many Cambodians were upset when President Barack Obama, one of many leaders attending a regional summit in Phnom Penh in November 2012, did not to pay his respects before Sihanouk’s body. He also reportedly had a tense personal meeting with Prime Minister Hun Sen criticizing him for his handling of human rights and democracy issues.

I first met the flamboyant and versatile prince in New York in the

1980s. I was fortunate to be invited to Sihanouk’s much coveted annual song and dance parties held at the Helmsley Hotel near United Nations headquarters. While the king’s parties were colorful and lively, with the monarch crooning renditions of Tea for Two and That’s What Friends Are For, a note of gloom hung over the occasions while his country was torn by civil war.

After Vietnamese troops and rebellious ex-Khmer Rouge soldiers ousted the murderous Khmer Rouge regime in January 1979, and installed the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) government which soon gained control over 90% of the country, the United Nations instead recognized the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK). The coalition operated from refugee camps situated in neighboring Thailand and included elements of the Khmer Rouge and Sihanouk’s royalist FUNCINPEC movement.

With the Cold War in full swing, the Soviet Union and its communist allies plus India and a number of nonaligned countries recognized the pro-Vietnam PRK government. Sihanouk’s annual soirees in New York were held while he campaigned for the CGDK headed by him against the PRK at the UN General Assembly.

This stalemate of two governments continued until the Paris Peace Accords were signed in October 1991, establishing the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia. UNTAC was tasked with holding elections and paving the way for national reconciliation. In November 1991, shortly after signing the Paris Peace Agreements, PRK Prime Minister Hun Sen welcomed king Sihanouk back from twelve years of exile.

“I wish to thank you, Excellency Mr Yasushi Akashi, for sending another prince from Java to help bring peace to Cambodia,” Sihanouk quipped in August 1992 to UNTAC’s then senior-most administrator in reference to myself. This was my second encounter with Sihanouk. The occasion for the quip was the inauguration of UNTAC’s provincial headquarters in Siemreap, near the Angkor Wat temple, where I served as a shadow governor for UNTAC. Akashi was the Japanese head of UNTAC while Sihanouk served as head of the Supreme National Council, a symbolic authority that represented Cambodian sovereignty during the UNTAC-led transitional period.

Sihanouk (hands clasped), Widyono and Akashi surrounded by bodyguards opening the Siem Reap provincial headquarters of UNTAC, August 1992. |

While not a prince, I did indeed hail from Java, Indonesia. Sihanouk’s learned joke baptizing me as the second prince of Java had its origins in the year 802, when Prince Jayavarman II was proclaimed a universal monarch, or Deva Raja, (God King). According to inscriptions, Jayawarmnan II spent some time in Java. To this day, the peasants who make up the bulk of Cambodia worship Sihanouk as the last Deva Raja of Cambodia.

During my UNTAC tenure, I got to know Sihanouk intimately. At one point, I was asked by my UNTAC superiors to accompany him by helicopter to the headquarters of the Khmer Rouge to see how they were preparing for the upcoming elections. Because he was using UNTAC helicopters, Sihanouk requested that a senior UNTAC person accompany him.

Although he was put under house arrest during most of the Khmer Rouge’s 1975-79 rule – during which an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians perished – Sihanouk had earlier made common cause with the group after the pro-American general Lon Nol overthrew his neutral government in a 1970 coup. Sihanouk went into exile in Beijing and obtained China’s help for the struggle to overthrow the Lon Nol regime dominated by the Khmer Rouge. He was thus seen by the UN as an important interlocutor to the Khmer Rouge, which had fought an effective guerilla campaign after being toppled by Vietnamese forces in 1979.

We boarded a small six-seater French military helicopter in Siem Reap and landed at Pailin, the lugubrious Khmer Rouge headquarters which was off limits to UNTAC. The pro-Khmer Rouge population who were trucked in from surrounding villages gave Sihanouk a thunderous welcome. They were attired in colorful new dresses imported from neighboring Thailand and looked relatively prosperous compared with the poverty-stricken people in nearby PRK -controlled areas.

At lunchtime I was invited to join a banquet of Khmer Rouge top brass in honor of the royal couple. Top Khmer Rouge leaders, including Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary, and Son Sen, and I flanked the prince and princess. Pol Pot, the radical group’s leader, was apparently lurking in a nearby room watching. Ieng Sary’s daughter, who had studied in London, prepared a sumptuous Khmer nouvelle cuisine lunch washed down with Mouton Cadet, Sihanouk’s favorite French wine.

From my vantage point at the end of the table, I was able to observe first hand the bizarre relationship between Sihanouk and the Khmer Rouge’s leadership. Their strange conversation that day centered on the concept of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary and Friday the 13th as a Western superstition.

The Khmer Rouge top brass continuously teased Sihanouk that he had stopped his amorous escapades after marrying Princess Monique, (now Queen Monineath) his sixth official wife. Sihanouk turned to me and confirmed with his inimitable cackle that Princess Monique kept him in chains and would never again allow him to look at other women.

Perpetual crisis

After UNTAC successfully held the elections and left Cambodia, I was appointed as the United Nations Secretary-General’s representative to the new Royal Government of Cambodia. It was then that I truly got to know Sihanouk. I arrived in April 1994 in time to watch yet another tumultuous welcome for Sihanouk, who arrived from Beijing at that time. The king was nominal head of the Royal Government of Cambodia, the post-election coalition that was recognized by all global countries.

Underscoring unresolved tensions, the government was headed by two Prime Ministers, Prince Ranariddh, Sihanouk’s son, and Hun Sen, the PRK’s prime minister since 1985. The Khmer Rouge, however, maintained their arms and continued to challenge the new coalition government’s authority from the territories it controlled.

On May 1, 1994, I was granted an audience with the king. After exchanging formalities, we were led to a smaller room with a huge map of Cambodia. Here, Sihanouk went into great detail in outlining the crisis caused by the Khmer Rouge’s then ongoing counter-offensive, which dominated our conversation that day.

In highly animated fashion, Sihanouk predicted that the Khmer Rouge, buoyed by its recent military successes, would try to proclaim a separate state in an outer northern crescent of territory bordering on Thailand. The king cackled and told me that behind the room’s huge curtains many spies were lurking with secret microphones linked variously to the Khmer Rouge, Ranariddh and Hun Sen.

That day, he was thinking aloud about what to do to save Cambodia from yet another crisis. He complained that the coalition government did not take him seriously while expressing a striking lack of confidence in the co-premiers. It was quite evident from our conversation that Sihanouk was unhappy with his position as a king who reigned but did not rule. “They wanted me to be somewhere up in the sky above Cambodia,” he told me at a private dinner to bid frewell to the Indonesian ambassador where he lamented agreeing to the co-premiers’ push to create a constitutional monarchy.

In June 1994, Sihanouk unveiled yet another plan to retake the reins of power. From self-exile in Beijing, where he would spend much of the rest of his life, he summoned veteran Far Eastern Economic Review journalist Nate Thayer for a long interview in which he accused the coalition government of being incapable of halting the deterioration of the country’s politics. “How can I avoid intervening in a few months’ time or one year’s time if the situation continues to deteriorate?” he asked during the bombshell interview. When Hun Sen wrote him a letter sharply criticizing him for the interview, the King vowed to retire from politics.

However, Sihanouk was never fully marginalized. He published his writings regularly in his Bulletin Mensual de Documentation (Monthly Bulletin), which can now be read on-line. He often handwrote biting letters, commentaries and annotations to newspaper and magazine articles on Cambodia in English and French, lavishly decorated by multiple exclamation marks and underlinings. The bulletin provided an outlet to criticize the governance of the co-premiers and wield influence.

When the coalition government became internally strained, the writings of a certain Ruom Rith suddenly appeared in his bulletin. Ostensibly, Ruom Rith was an old friend of the king; he was his exact age and supposedly lived somewhere in the French Pyrenees. They shared identical writing styles, alive with exclamation points and multiple—up to four or five in a row—question marks. Whereas the king was restrained in criticizing Hun Sen, Ruom Rith was quite outspoken.

It was commonly believed in Phnom Penh that Ruom Rith was a pen name for the king himself – although the monarch vigorously denied it. Later, during tense periods leading up to the bloody 1997 confrontation that left Hun Sen as the only prime minister, other alter egos of the king appeared. In some instances, they even began to argue with each other in the bulletin. The king appeared to enjoy this role play, choreographing with obvious amusement his own private puppet show.

Since 1997, Hun Sen has consolidated his power as prime minister and his political party, the Cambodian People’s Party, won increasingly larger majorities. In the latest elections, in 2008, the party took 90 seats in the 123 member legislature. It appears almost certain that Hun Sen will easily win another five year term in the forthcoming elections in July 2013.

Due to poor health, and perhaps realizing that his political role was over, Sihanouk abdicated the throne for a second time in 2004. He handed down the crown to his unmarried and childless youngest son Norodom Sihamoni. King Sihamoni is a 59-year-old former ballet dancer who had spent most of his life in European artistic circles and has proven a low-keyed constitutional monarch in a country dominated by Prime Minister Hun Sen. Sihanouk had one life long ambition that remained unfulfilled: to rule over a prosperous and peaceful Cambodia. After Sihanouk stepped down, the National Assembly bestowed the title of “the Great King Hero, Father of Independence, of Territorial Integrity and National Unity” on the former monarch and politician. He spent most of the rest of his life in Beijing undergoing treatment for various illnesses. Today, the government bestowed a new title on Sihanouk, “Preah Borom Rattanak Koat”, while a new 1,000 riel note (about 25 US cents) bears the image of the golden funeral carriage.

At the cremation ceremonies, most Cambodians will indeed remember Sihanouk as the father of Cambodia, the man who gave them independence, strived for peace and reconciliation and ultimately saved their small, but distinct country from disappearing from the map. Many believe that while the royals remain highly revered by many elderly Cambodians, the monarchy is growing less relevant in the eyes of the younger generation. Today, under the strong rule of prime minister Hun Sen, the country is enjoying two decades of fast economic growth and in Phnom Penh, the sky is dotted with skyscrapers, with more under construction. The youth of Cambodia today; like their peers in neighboring ASEAN countries, appear to be more interested in graduating from college and getting a job than in politics.

Benny Widyono is a retired United Nations civil servant from Indonesia. His last position was the UN secretary-general’s representative in Cambodia, 1994-97. He is the author of Dancing in Shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge and the United Nations in Cambodia. (Rowman and Littlefield, 2007).

Recommended Citation: Benny Widyono, “The Sihanouk Era: The King and I,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 11, Issue 6, No. 1, February 11, 2013.

Articles on related themes

• Geoff Gunn, The Passing of Sihanouk: Monarchic Manipulation and the Search for Autonomy in the Kingdom of Cambodia

• Fred A. Wilcox, Dead Forests, Dying People: Agent Orange & Chemical Warfare in Vietnam

• Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism

• Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen, Roots of U.S. Troubles in Afghanistan: Civilian Bombing Casualties and the Cambodian Precedent

• Nick Turse, A My Lai a Month: How the US Fought the Vietnam War

• David McNeill, Suffer little Children: Legacies of War in Cambodia

• Taylor Owen and Ben Kiernan, Bombs Over Cambodia: New Light on US Air War