[Figure 1] |

Manga is an art that should warn of or actively attack all things in the world that are unjust, irrational, unnatural, or incongruous with the will of the nation.

– Kato Etsuro, “Shin rinen manga no giho” (Techniques for a New Manga), 1942

Yasukuni Shrine is the final stronghold in defence of the history, spirit, and culture of Japan.

– Kobayashi Yoshinori, Yasukuniron, 2005

In 1992, just as Japan’s economic bubble was in process of bursting, a series of manga began to appear in the weekly Japanese tabloid SPA! under the title Gomanism sengen (Haughtiness or Insolence Manifesto).2 Authored by Kobayashi Yoshinori (b. 1953), this series blurred the line between manga and graphic novel to engage in forthright social and political commentary with an unabashedly nationalistic slant. Over the following two decades, Kobayashi and his works have become a publishing phenomenon. As of 2013, there are over thirty volumes of Gomanism (and Neo-Gomanism) manga, including several “special editions”—such as the best-selling Shin gomanizumu sengen special: Sensoron (Neo-Gomanism Manifesto Special: On War, 1998) and, more recently, Gomanizumu sengen special: Tennoron (Gomanism Manifesto Special: On the Emperor, 2009)—that have caused controversy and even international criticism for their revisionist portrayal of modern Japanese history. At its most general, Gōmanism is a graphic and rhetorical style marked by withering sarcasm and blustering anger at what is perceived as Japanese capitulation to the West and China on matters of foreign policy and the treatment of recent East Asian history. Its very success, however, warrants closer treatment, particular with the perceived rise in nationalistic feeling associated with the new Liberal Democratic Party administration of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō.

In 2005, Kobayashi published a graphic work entitled Shin gomanizumu sengen special: Yasukuniron (Neo-Gomanism Manifesto Special: On Yasukuni), which tackles the much-debated “problem” of Yasukuni Shrine, the militaristic religious complex that has become a lightning-rod for debates regarding Japanese historical memory—especially with regard to the military expansionism in East Asia that led to the Asia-Pacific War (1931–1945). Frequently overlooked in discussions of Yasukuni, however, are a number of complex issues related to its religious doctrines—in particular, the interpretation of Shinto presented at Yasukuni and the dominant ideology of Japan’s military era, so-called “State Shinto” (kokka Shinto). This essay examines the portrayal of the Yasukuni Issue within Yasukuniron, in order to: a) flesh out the characteristics of Kobayashi’s Gomanism in relation to the “theology” of State Shinto; b) examine the power and limits of manga as a representational form for teaching about the complex nexus of religion, politics and history in modern Japan. Finally, I connect this work with the more recent Tennoron, particularly with regard to the status of the emperor as a “god” (kami).

[Figure 2] Depictions of war dead as “heroic spirits” (from left to right, pp. 41, 19, 45, 137) |

[Figure 3] External others as “monsters” (from left to right pp. 14, 121, 138) |

Yasukuni and the Legacy of State Shinto

The shrine that would become Yasukuni was founded in 1869, a year following the Meiji Restoration, as a place for “pacifying” the spirits of all those killed in wars fought for the “nation.” Originally known as Tokyo Shokonsha (literally, Tokyo shrine for the invocation of the dead), the name was changed to Yasukuni Jinja in 1879 at the behest of the Meiji Emperor. As Kobayashi notes, “Yasukuni” was chosen to imply “pacify the nation,” and in a (State) Shinto context this was understood to mean that the primary if not sole purpose of this shrine was to pacify the spirits of the war dead, which would help bring tranquility (and protection) to the national body (kokutai).3 Administered directly by the ministries of the Army and Navy, by the time of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), Yasukuni had entered into popular consciousness as a symbol of Japanese imperial conquest and a focus for the state-sponsored cult of the war dead. Today, Yasukuni enshrines the “souls” of 2.5 million people, including roughly 57,000 women, 21,000 Koreans, 28,000 Taiwanese, at least three Britons and, most controversially by far, 14 individuals indicted as “Class A” war criminals.4 All of these men and women “offered their lives to the nation in the upheavals that brought forth the modern state” between 1853 and the present. As such, according to Kobayashi (and Yasukuni itself), those enshrined at Yasukuni are anything but “mere victims” (tan naru giseisha). They are rather “martyrs” (junnansha), “heroic spirits” (eirei), and “(protective) gods of the nation” (gokokushin). As we shall see, the intertwined tropes of martyrdom and victimhood play an important role in the attempt to “restore” Yasukuni—and by extension, the true Japanese spirit and identity.

In contrast to the coverage of the various political issues raised by Yasukuni, the more specific religious or “theological” elements are often overlooked in popular coverage as well as within scholarly analysis. Yasukuni is, after all, a “shrine,” and one that has played a central role in the formulation and expression of a particular religious ideology that is known today as “State Shinto” (kokka Shinto). While there remains much debate over the precise meaning of State Shinto, there is consensus that modern Shinto nationalism has roots in the so-called National Learning or Nativist School (kokugaku) of the mid- to late Edo period (1600–1867). While Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801) is the most significant early Figure in Shinto revivalism, it was his self-proclaimed successor, Hirata Atsutane (1776–1843), who transFigured nativist doctrine into a more “heroic” and populist form, focused on loyalty, patriotism and attunement to the spirits of the dead.

The basic “theology” of State Shinto, at least in its later, wartime incarnation, might be summarized as follows: (a) all Japanese belong to a single national body (kokutai), whose “head” is the emperor—not any specific person so much as the “unbroken” Yamato imperial line; (b) the Imperial House, by virtue of its lineal connection to the heavenly kami, as confirmed in the sacred classics, is sacrosanct and inviolable; (c) all Japanese, by virtue of being members of the national body, owe their complete allegiance and filial piety to the emperor, a living kami; (d) by extension, all Japanese must obey the directives of the (imperial) state, even to the point of giving their lives for the kokutai. This is also the theological foundation of Yasukuni Shrine—albeit with a greater emphasis on the glories of self-sacrifice and martyrdom. As I will show in this essay, while Kobayashi’s manga revisioningof Yasukuni also relies on this basic set of theological or ideological premises, Yasukuniron indicates a subtle but significant shift in focus away from the ancient period, the Imperial House and the state and towards a populist, modernist and possibly fascist rendering of “State Shinto.” I am using the term “revisioning” deliberately to refer to two things: (a) the technique of “revisionist” history—which Yasukuniron certainly engages in; and (b) the more literal sense of “making over” or “recreating Yasukuni in a visual way” via the evocative graphic techniques of manga.

[Figure 4] Slavish politicians, p. 9 |

The Gomanist Truth about the Yasukuni problem

The title of the preface to Yasukuniron—“The Ignorance behind the Yasukuni Problem” (“Muchi ni yoru Yasukuni mondai”)5—is pure Gomanism. Here and throughout the manga Kobayashi asserts that the entire “problem” of Yasukuni is based on a widespread (at times, it would seem, universal) ignorance of the various issues involved, an ignorance willfully perpetuated by national politicians and the (“left-wing”) mass media. However, the Truth is out there (or rather, in here, i.e., the pages of Yasukuniron), and possession of that Truth will set us all free from our collective blindness. In short, do not expect to find here any postmodern prevarications about the nature of truth and reality. It can and will be uncovered, using “objective” methods of historical investigation (coupled, of course, with stark and frequently disturbing visuals).6

However, Kobayashi and his manga avatar (who I will refer to as K) are not only waging a battle against ignorance, for such ignorance is aided and abetted by cowardice and moral failure. We see this visualised on page 22, where K practically jumps out of the frame to declaim that, unless the nation “has the balls” to restore Yasukuni Shrine to its rightful place, there will be no hope of a “Japanese restoration” (or perhaps, a “revival of the Japanese people”).7 This is the underlying theme of the work, and makes for a narrative whose storyline is epic in structure, with the lone hero—the manga-fied everyman K—engaged in a quest against enemies of various sorts.8 The reader is invited to identify with the author via his avatar, and thus become a part of the battle for the restoration of Truth. This is visualized most clearly on page 12, where, after the formulaic query/call to arms: “Goman kamashite yoka desu ka?” (“Will you permit me to be a little insolent?”), the reader is explicitly invited to join the quest for the truth (shinjitsu) about Yasukuni, in order to help rescue the nation from its “shameful” state brought about by the misinformation of the unholy triumvirate of “politicians, scholars and the mass media.”

The argument of Yasukuniron works in piecemeal fashion, a form which is not only well-suited to manga format but also reflects a particular style of academic discourse in Japan, where linear structure tends to be considerably less important than in the West. As an opening gambit, Yasukuniron begins with a stark example of popular misunderstanding regarding Yasukuni—in this case, ignorance the Shinto doctrine and practice of bunshi (literally, “separation of worship,” but best translated as ‘the ritual separation and transfer of an enshrined kami to another shrine’).9 After noting, quite correctly, that politicians in the National Diet frequently call for the “separation” of the enshrined Class A war criminals at Yasukuni, K argues that the ritual process of bunshi in Shinto is akin to the transfer of a flame from one candle to another; in each case, nothing is lost of the original. On the contrary, the original flame/kami is by this means effectively multiplied (thus quite the opposite of our common-sense understanding of “separation”). Before coming to the conclusion of this mini set piece, K adds a personal anecdote. He too, we (literally) “see,” is briefly puzzled by the fact that a small shrine in his Tokyo neighborhood could be dedicated to Okununushi (a popular kami who plays a significant role in the early chronicles Kojiki and Nihon shoki), when this kami’s “home” is the grand Izumo Taisha in distant Shimane prefecture. The answer is, of course, that he/we/politicians do not get the true meaning of bunshi, in which is it quite reasonable to have a single kami enshrined in hundreds or even—with major kami like Inari, Tenjin and Hachiman—tens of thousands of shrines. And yet: “This is the Shinto idea.” Then the climax, with a mocking K pointing his finger: “If you were to ‘separate’ the Class A war criminals, General Tojo and the rest would remain in Yasukuni as well as appear in the new location . . . If this is what you want, then by all means, go ahead and ‘separate’!”10

This brief tableau bears analysis, since it is representative of the style that characterises all of Kobayashi’s Gomanist manga. While K’s presentation of the Shinto doctrine and ritual of bunshi is quite correct, it is here employed in a classic case of rhetorical bait and switch. When politicians, commentators or scholars call for a “separation” of Class A war criminals from Yasukuni, they are not referring to the “orthodox” doctrine of bunshi, but rather to the more elusive—and, it has been argued, palpably modern—idea of the souls of Yasukuni being enshrined as a collective unit; i.e., a mass tama without distinction.11 This, at least according to the shrine itself, is the primary reason that the souls cannot be “separated.” As Yasukuni head priest Matsudaira Nagayoshi (1915–2005) explained in 1987:

|

That [i.e., separation] is absolutely impossible. In this shrine there is something called a ‘seat’ (za), which acts as a cushion (zabuton) for the kami. In shrines other than Yasukuni, such a “seat” does not exist. The 2.5 million soul-pillars rest on the same cushion. It is impossible to separate them from this (hikihansu koto wa dekimasen).12

After a panel in which K notes that, in any event, only “atheists” and “materialists” would conceive of telling certain enshrined kami that they alone are a “bother” (jama) and need to placed elsewhere, this first salvo is quickly followed by an equally derisive rejection of the alternative proposal: to build a national “non-religious” memorial for the war dead (kokuritsu tsuito shisetsu). K’s point here is reliant entirely on emotion, based on a staple trope of Yasukuni war remembrance: the final promise of imperial soldiers to their comrades and loved ones that they would “meet again at Yasukuni.” He asks, with a sneer, whether politicians are prepared to say to these men (or their departed souls), just sixty years after the war’s end, that instead of Yasukuni they will have to settle for a posthumous rendezvous at the “National Memorial Facility.” This argument is continued throughout chapter four, in which K—surely aware of the irony given the historical connection between Yasukuni and State Shinto—accuses the Koizumi administration (and opposition) of attempting to create a “new religion” for the state, one that attempts to bypass the rituals of Shinto, Buddhism and Christianity, but ends up being merely a religion without substance.13

All throughout, the reader is peppered with images of various sorts: some realistic (K’s face, the neighborhood shrine), others comic (caricatures of various politicians), and still others abstract (tadpole-like souls swimming through the air, in search of their proper home) or palpably symbolic (a Shinto torii bathed in a bright glow). The author adds a panel above the images, in which he provides another layer of comment. Here, in the Gomanist equivalent of a scholarly footnote, we read that while Shinto forms the basis of an unconscious ethos for all Japanese, it has only weak prescriptions for regulating external behavior—this is why commentators are led to the mistaken conclusion that Shinto is “flexible” (yuzu ga kikumono) and therefore open to change at the whim of politics.14 While it is certainly true that premodern Shinto lacks the formality of doctrine found in most religious traditions, and is therefore, one might argue, more susceptible to political manipulation, the assumption that Shinto forms the unconscious core of the Japanese ethos is one that deserves more attention. I will return to this later in the essay.

Chapter one—“The Truth about Yasukuni Group Enshrinement, which is Unknown to National Diet Members” (“Kokkai giin ga shiranai Yasukuni gōshi no shinjitsu”)—picks up the theme of the ignorance of politicians in relation to the Yasukuni doctrine of “group enshrinement” (gōshi). The opening pages, however, are devoted to reflection on the nature of war (as a nearly-universal modern phenomenon, usually begun by Western powers), buttressed by a by-now familiar litany regarding the illegitimacy (i.e. “victor’s justice”) of both the Tokyo War Crimes Trial and San Francisco Peace Treaty. Noting that most of the contemporary debate on Yasukuni surrounds the issue of the 1978 enshrinement of the fourteen “Class A” war criminals, K boldly asserts that, in fact, this debate is based on a false premise: i.e., that these men actually were/are “Class A war criminals.” In fact, K asserts, citing the dissenting opinion of Indian Judge Pal, they—along with another 1850 or so “war criminals”—are rather collective victims, even “martyrs” (junnan shisha) of a “ceremony of savage retribution” (yaban na hōfuku no gishiki) waged by the victorious Allies.15

Here the argument begins to turn away from the opinions of weak-kneed politicians and leftist media towards that of the Japanese people, who, K claims, stand squarely on the right side of truth. On the one hand, Kobayashi Gomanism leans heavily on the appeal of the author (and his avatars) as a lone crusader fighting for truth and justice, but in order to succeed he must also hearken to ethnic populism: “we” ordinary Japanese know the truth, even if our so-called leaders do not. As is familiar in contemporary conservative populism wherever it is found, a sharp divide is thus established between the elites (i.e., intellectuals, media, government) and the people (however vaguely defined). While there is thus recognition of a national “personality split,” it is one that may be healed over time, if we are willing to take the necessary steps.16

In Yasukuniron, this tension is resolved in the following fashion: postwar Japanese (including the bulk of politicians and media) were quite content with the postwar meaning of Yasukuni, but they have since either: (a) lost interest because caught up in a “materialist” culture; or (b) been negatively influenced by a few leftist politicians and the mass media, who since 1985 have effectively created the Yasukuni “problem.”17 In short, this is the story of a collective, and fairy recent, fall into ignorance—albeit one that is not primarily the fault of the people.18 The organic metaphor here is (disturbingly) familiar: the nation is sick, and requires a strong dose of medicine—i.e., Gomanism—to be brought back to health.

[Figure 6] Violence of the internal other, p. 12 |

[Figure 7] Violence of the external other, p. 46 |

Throughout this chapter, as elsewhere in Yasukuniron, the argument is broken up by episodes of unabashed sentiment, or what we might call “human interest” stories: first a one-page aside regarding an emotional song written by several “war criminals” in a Philippine jail cell, which not only became a hit in postwar Japan but had such an effect on the Philippine president that he was moved to release all Japanese prisoners of war; then a brief vignette regarding the author’s reception of a certificate (saishin no ki) from Yasukuni noting the posthumous “deification” of his own grandfather, who perished in Siberia during the war, and his decision in 1999 to contribute a manga-decorated lantern to Yasukuni for display during the annual Mitama Matsuri (several of which are reproduced in the manga).19

Finally, just prior to the chapter’s close with a rousing call-to-arms, K begins another counter-argument against those who claim that Yasukuni is in fact a modern and derivative version of (State) Shinto, a nationalist ideology that is not representative of anything in Japanese religion, tradition or custom. This point is further elaborated in chapter two, where it makes up a large part of K’s analysis of the Japanese public’s “fall” away from the truth about Yasukuni. As my analysis here is based primarily on the religious claims of Yasukuni and Yasukuniron, this is a “rebuttal” that requires further attention. After establishing the black and white scenario of “us” vs. “them” throughout chapter one, K gives us a very brief history of Shinto, in which he admits that what we call “Shinto” has ‘naturally transformed over the course of history’. In short, though “Shinto may have a ‘foundation’, it is not thereby ‘fundamentalist’.”

On the face of it, this seems a striking admission, since it runs against a common understanding of Shinto as the unchanging substructure (or, as K put it in the preface) “unconscious ethos” of the Japanese people. However, with recent trends in Shinto scholarship—notably after the work of Kuroda Toshio, and more recently in the writings of John Breen and Mark Teeuwen—which question the very existence of anything we can reasonably call “Shinto” prior to the eighteenth century, Kobayashi could hardly rely on such an uncritical ahistorical essentialism (K admits in particular the significant impact of Buddhism on Shinto, though the example provided is of architectural rather than doctrinal influence). K’s reply, here and in chapter two, is more subtle: (a) Yasukuni Shrine may be a “modern” creation, but this is simply because it is dedicated to the construction of Japan as a modern nation; since this is a set of conditions that never existed in the past, there was literally no need for such a shrine before the Meiji Restoration; (b) following on this, he asks, by what criterion do we call something a “tradition” or “custom”? Is Meiji Shrine, K asks, also a product of the modern period, not a traditional shrine? (c) on the other hand, Yasukuni is rooted in an ancient tradition, i.e., the longstanding Japanese practice of “ancestor worship” (sosen sūhai).20

Thus, K argues, while Yasukuni as an institution may have “modern” elements, it is squarely rooted in an ancient Japanese tradition of reverence for the spirits of the dead—whatever one might choose to call that tradition. Here we see a subtle but important shift away from “Shinto” to the practice of ancestor veneration as the root of Japanese spirit, culture and identity.

Envisioning (with) the Dead

Embedded within Kobayashi’s treatment is a portrayal of Yasukuni, and by extension, the enshrined heroes who sacrificed their lives to build a modern Japan, and whose souls continue to protect Japan, as “victims” of widespread (internal) ignorance and (external) violence. The violence of which the imperial army—and particularly the individuals judged as war criminals—is so often accused is here turned around against the accusers. This is dramatically visualized throughout Yasukuniron, in which every single image of the heroic dead is presented in a form that scholars of fascism would identify as kitsch—i.e., unambiguously sentimentalized, to the point of caricature (Figure 2), while the faces and Figures of the “others”—especially Chinese and Koreans—are generally rendered as ugly, cruel and vindictive monsters (Figure 3).

This applies to a lesser extent to the depiction of Westerners as well as “internal others”—i.e., politicians, the mass media and leftist activists and intellectuals—though the latter are more often depicted as being pathetic/slavish (politicians) or fanatics (leftists, media) (Figures 4 and 5).

In all cases, the emphasis is clearly on the violence, both literal and figurative, that has been and continues to be done to Yasukuni-qua-the heroic dead-qua-“the Japanese” by others. The menace of internal violence is perfectly encapsulated in a small frame (see Figures 6 and 7, below), which depicts two leering Figures with a newspaper representing the media, activists and politicians extending out of the Japanese islands to drop flaming torii on the heads of what are presumably ordinary Japanese people, who scramble about in a panic (Figure 6), while the spectre of external violence is dramatically depicted in several images on page 46, which show the “ethnic character” of Japan literally melting away (subete massatsu shite), while foreigners (holding their respective national flags) look on with disdain, egged on by Japanese leftists who call for increasing “globalization” (Figure 7).

Revisioning (State) Shinto as Peace

In order to support the claim that Yasukuni is a legitimate and traditional representation of Japanese spirituality and identity and not (simply) a political or nationalist symbol as it is so often represented, K presents the doctrine and practice of Yasukuni as being founded on Japanese ancestor veneration, which is itself a specific instance of a more general desire to bring peace and harmony both to one’s loved ones and to the community at large. Here the argument runs in several directions. First, it includes an attempt to render the Japanese practice of “comforting the dead” a natural and universal aspect of “national character”—i.e., an (inviolable) part of culture and tradition—and thus “completely distinct from a practice that is rooted in nation or ethnicity.”

At the same time, there are important differences between the various religious understandings of the afterlife. As opposed to Christianity, K asserts, where spirits are called home to be with the one God, in Japanese polytheism kami can be found literally anywhere and everywhere, and those who die are automatically considered to be kami or buddhas. Moreover, as opposed to the Christian separation of this world and the next, for “we Japanese,” the dead remain among us, even, as the accompanying graphic indicates, within the hustle and bustle of urbanized modern life. So far, this argument suggests that non-Japanese should understand and respect these differences in the Japanese understanding of the afterlife. There is also here an implication that the Japanese have a closer, more immediate relation to the dead, who live among them, than do Christians—and this difference plays a role in understanding the importance of Yasukuni to the Japanese national character and identity.

But the discussion of religious differences does not end there; on pages 42 and 43 K presents a sharp contrast between the peaceful and tolerant Japanese afterlife (where everyone is automatically raised to the status of a kami or buddha), and the Chinese belief, “in which the flesh of the dead is torn off their bones by their bitter enemies, and the bones are ground to a powder, which is then consumed.”21 In short, while Yasukuni Shinto is based on a universal need to comfort the dead, the unique elements of the traditional Japanese concept of the afterlife provide a tenor of tolerance and peace that is in stark contrast to that found in countries such as China (Figures 8 and 9)—which, hypocritically but perhaps unsurprisingly, practices the very same form of posthumous violence on the Japanese war dead as they imagine happens in the Chinese afterlife!

[Figure 8] Chinese afterlife, p. 42 |

[Figure 9] Japanese afterlife, p. 42 |

Without getting into the fact that both Chinese and Japanese understandings of the afterlife are extremely varied (largely as a result of both countries having complex and highly syncretic religious histories), we might note that K’s analysis leaves out the deeply rooted Sino-Japanese conception of the dead as “restless” and potentially “wrathful” spirits (onryo or goryo) caught in a state of limbo—a popular belief that has roots that date to the ninth century, and very much continues to this day (as witnessed by the success of recent Japanese horror films like The Ring (Ringu) and The Grudge (Juon). More to the point, it would appear that this belief in wrathful spirits was the primary instigation for the establishment of Yasukuni Shrine itself as a place to “pacify” the spirits of the war dead. In other words, the shine may have originally been intended not to protect the souls of the heroic dead, but rather to protect the living from their unsettled wrath!22 While this is clearly not an idea promoted by either Yasukuni or the associated Yushukan museum today, it does relate, however unintentionally, to Kobayashi’s implication that his heroic spirits have every right to be wrathful. Throughout the manga, K frames the act of pilgrimage to Yasukuni in terms of both honoring and pacifying the spirits—albeit less for their violent deaths in battle as for what they have suffered since the war.

Individuation and Nationalization of the “Heroic Spirits”

One of the central tensions in Yasukuni Shinto is that between the deceased spirits as individuals—with distinctive personalities, ambitions and family relationships, and as subjects—i.e., embodiments of the national spirit of heroism, loyalty and sacrifice to the Emperor and nation in the face of near-certain death. Within State Shinto logic, this was normally glossed with the notion that the Imperial State is an extension of the family, and thus all individualized feelings and duties must be sublimated (or sacrificed) to the higher calling of national loyalty. In practice, what we see is an accommodation to individuation of the heroic dead, at least within certain limits. On a practical level, of course, it would be impossible to deny the emotional connection between the war dead enshrined at Yasukuni and their loved ones left behind—not least because of the fact that this is (unsurprisingly) a central theme of so many of their letters and diaries. Moreover, the emotional bond is what brings many to the shrine itself; family members go to Yasukuni to “meet” and “pray for/to” their deceased kin. The “doctrinal” facts that these individuals have been posthumously elevated into mikoto or kamigami, and thus separated from all worldly ties, or rendered into a single mass tama/kami that protects the nation, hold little resonance for Yasukuni visitors, who approach the dead as they would at any Buddhist temple or family altar. And this extends even to those without enshrined family members. Indeed, the final chamber of the Yushukan museum, which displays the personal letters of hundreds of these young men, is by far the most moving part of the museum. Whatever one’s politics, it is hard not to be stirred by the words of these men—particularly when they speak of their parents and children. What is missing, of course, is any sense that these men may have been divided in their loyalties, or hesitant to sacrifice themselves for the Emperor and “family-state.” While they are thus individuated in terms of the specifics of their letters, these same letters take on a standard form that serves to erase any trace of resistance. It goes without saying that a more comprehensive analysis of the writings of the Japanese military during the war—including the tokkotai or kamikaze pilots—provides a much more diverse field of perspectives.23

Manga as Tool for Revival of the Japanese “Spirit”

Though Kobayashi’s manga are presented as expressions of his own personal (and self-consciously “insolent”) opinions, their very popularity betrays a receptive audience of like-minded readers, and renders them worthy of study as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Moreover, Kobayashi’s personal links to the revisionist Liberal Historiography Study Group (Jiyushugi Shikan Kenkyukai), the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashii Rekishi Kyokasho o Tsukurukai), as well as the Japan Conference (Nihon Kaigi) suggest a larger goal of educational, social and religious—if not outright political—transformation. The reader is explicitly invited to join the fight for a revival of the true Japanese spirit or culture—rooted in the virtues of respect, filial piety, national pride, self-sacrifice and, last but not least, a sense of “heroic history.” To do so, however, they/we must first identify with Yasukuni, which both symbolizes this spirit and literally “embodies” the victimhood of the nation’s heroes to the continuing violence of “others.” Thus, what is aimed for here is more than simply a “closed community of mourning,” since the process of individuated and collective mourning is conceived as a form of self and communal realization.24

In short, though it thrives on a bombastic method of “insolence,” Kobayashi’s Gomanism is, at bottom a technique of subjectivity; i.e., an ideology that looks to reconstruct a (national) identity via individual conversion. Crucially, this conversion takes place through identification—which is at least as much a visual and emotive process as a cognitive one. And it is a conversion that can only effectively take place at Yasukuni Shrine. In all of these senses, Gomanism here, as elsewhere, is committed to the paligenetic imperative, which Roger Griffin has argued is central to fascism; i.e., the myth of the a “purifying, cathartic, national rebirth.”25

The trope of (national-cum-individual) sickness, humiliation and victimhood followed by an apotheosis of rebirth is visually encapsulated in the final page of chapter seven (previously published in Sensoron II), in which K stands, Christ-like, in front of the mass of ordinary Japanese, urging “us” to recognize that the very world in which we live has been constructed on the pillars of those who sacrificed their lives in the war (Figure 12). Here, the visual turns things around, so that the invited reader is placed in a position behind the spirits (who appear in their usual ghostly, benevolent form), facing K and those who have already realized the truth.26

In its unspecified promise of both communal healing and individual redemption, here, as elsewhere, the imagery resonates with Griffin’s analysis of the fascist mythos, which attempts to “unleash strong affective energies” through a vision of reality by positing an organic nation in a state of decay that, because it possesses a life cycle, can be revitalized through the manipulation of a group psyche. What is distinctive here, however, is that rather than “appealing to individuals to sacrifice themselves for a destiny that will bring them greatness,” the reader is invited to simply identify with those who have done the “work” of sacrifice; i.e., those who remain unsettled due to our lack of recognition.

“Land of Kami, Land of the Dead”

This brings us back to the issue of death, deification, and pacification in relation to the intertwined theologies of State Shinto, Yasukuni Shrine and Yasukuniron. The concluding chapter to the manga—“The Land of Kami is the Land of the Dead” (“Kami no kuni wa shisha no kuni demo aru”)—provides us with an effective re-entry point. It begins with several questions, posed as a challenge to the reader: Have we Japanese become a-religious (mushukyo)? Have we Japanese embraced materialism (muibutsuron)? After a few short vignettes depicting key events in the author’s life, each of which concludes with the familiar image of a deceased spirit hovering above, K begins to “pay attention to the glance” of the spirits of the deceased—who are very much “living with us.” In order to more fully hear what the spirits are trying to convey to him, he decides to pay homage to the dead at Yasukuni Shrine, where he becomes enveloped with a feeling of “public spirit” (koteki na kimochi).

If it were not already evident, by the final chapter of Yasukuniron the basic “theology” of Yasukuni—at least in Kobayashi’s interpretation—becomes clear. The shrine is a place in which we the living can go to meet with the dead. By paying homage at the shrine (in “traditional” manner), and by simply “paying attention” to these spirits via an exchange of glances, we confirm our own history and establish both our individual and national identity. In short, we are engaging in a populist version of “spirit pacification” (tamashizume or chinkon), a ritual that dates back to the original “State Shinto” instituted under Emperor Tenmu in the late-seventh and early-eighth centuries CE. As Naumann has argued, state cult ceremonies of this time seem to have been centered on petitions, thanksgiving and warding off evil. Pacification of Spirit ceremonies were among the most important rites for imperial-cum-state protection. Performed near the winter solstice, the primary goal of chinkonsai was the restoration of the vital power (tama) of the emperor in analogy to the sun (and the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu).27 In a later context, the pacification of spirits took on a quite different sense, with the introduction (from the continent) of the belief that once a person dies, their soul or spirit (tama) lingers in an unsettled state until it is correctly “addressed” by the proper funeral rituals and appropriate period of mourning.

[Figure 10] K inviting us to see the spirits, p. 146 |

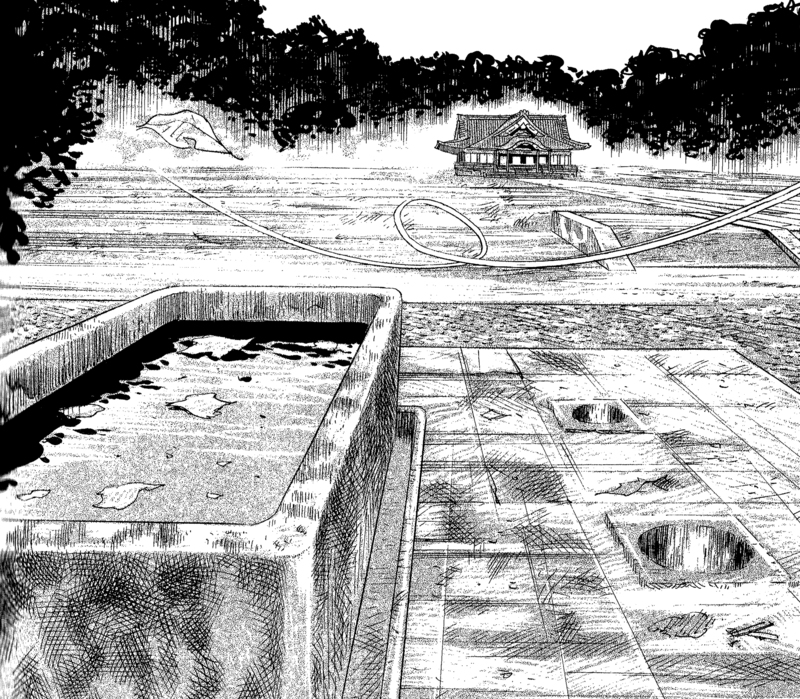

[Figure 11] Yasukuni, if left unprotected, p. 196 |

From the mid-Heian period, a belief in onryo or “vengeful ghosts” became widespread among both elites and commoners. According to this idea, unsettled spirits—those wronged in life, or whose death came under less than ideal circumstances—would cause all sorts of trouble to those left behind, especially but not exclusively their enemies. The classic instance of this is the posthumous deification of the courtier Sugawara no Michizane (845–903) as Tenman-tenjin in the tenth century. In any event, due to an early Shinto sense of death itself as a form of impurity and pollution, in Japan Buddhism has largely been the tradition responsible for dealing with matters of death, and specific rituals (kuyo) were developed in order to appease and pacify these spirits.28 Interestingly, though these ideas about death and the afterlife seem to elide well—even sharing key terms—with certain aspects of State Shinto, the Buddhistic focus on individual spirits who are or may be unsettled runs against several other elements of State Shinto and Yasukuni doctrine and ritual practice—in particular the understanding that the process of divinization is one in which the souls of the dead heroes are enshrined en masse, as a collective and inseparable unit. As we have seen, in Yasukuniron, as in the Yushukan museum, the emphasis is squarely placed on the human side of the story, with the dead heroes visualized clearly by the bereaved (and the reader) as idealized, peaceful and individuated spirits, chagrined only by the lack of respect that is given them in contemporary Japan.

Finally, a key aspect of Yasukuni theology—again, as interpreted through the lens of Yasukuniron—is the importance of pilgrimage. Although Kobayashi makes note of the Mitama Festival, held in mid-July at Yasukuni for the “consolation” (nagusameru) of the souls of the dead, he places greater emphasis on the necessity of regular visitations to the shrine as the most effective way of consoling the heroic spirits, via a process of memorialization and identification. But pilgrimage can also be understood as a means of self-purification on the part of the pilgrim. As Brian Bocking notes, in Japan this concept dates back to the medieval Watarai priestly lineage, who promoted pilgrimage to the Outer (Gekū) Shrine at Ise as a form of “self-purification, progress towards enlightenment and the uncovering of the inborn spiritual values of purity, honesty and compassion.”29 In Yasukuniron, it is through an exchange of “glances” that the consolation-qua-identification-qua-purification takes place, and this requires that the spirits be individuated as much as possible, even while conforming to a particular “type.” Though the rhetoric of their day called on these young men and women to “extinguish themselves through service to the state” (messhi hōkō), at Yasukuni and in Yasukuniron they are invoked as individuated spirits still very much among us. It is only our neglect of Yasukuni that puts them (and by extension, us) in danger of being extinguished. According to Kobayashi, Japan is indeed a “land of kami,” but, even more importantly, it is a “land of the (living) dead.”

An Imperial Absence

It is interesting to note that for all of the emphasis on sacrifice and heroism found in the pages of Yasukuniron, the Figure who, in State Shinto ideology, is the presumed focus for such loyalty—the literal and figurative “head” of the national body—is virtually absent. Indeed, just as he has not been seen at Yasukuni Shrine itself for thirty years, the emperor is hardly even mentioned in Kobayashi’s tribute to Yasukuni.30 With respect to the theology of Yasukuni/Yasukuniron, we might conclude from this that: (a) the emperor, just as he did during the period of ultra-nationalism (and before), functions more as an “empty” symbol than a real presence;31 or (b) the lack of the Emperor suggests a turn towards a more populist appeal to the war dead as “our heroic ancestors”—and the “pillars” (hashira) upon which the modern state has been constructed. In other words, though this could hardly be admitted, perhaps this absence masks an understanding that we have reached the stage where the national body no longer needs a head in order to function.

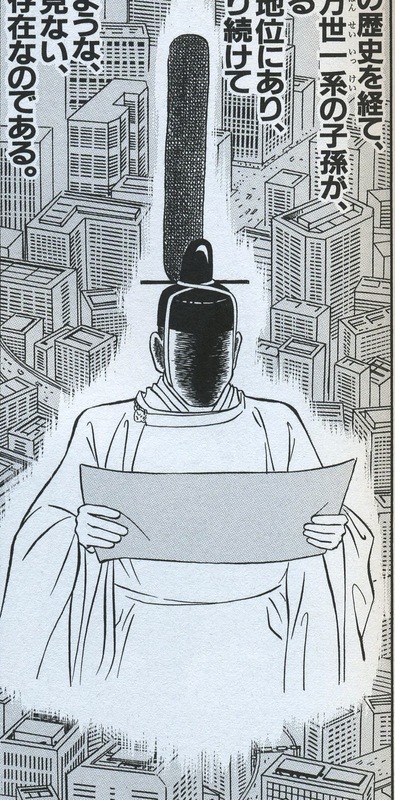

This is not to say that Kobayashi has been silent on the issue of the Emperor and his relevance to contemporary Japan. As if to make up for the lack of attention paid to the tenno in Yasukuniron, in 2009 Kobayashi published a new “Gomanist Special Edition” entirely dedicated to correcting “our” mistaken notions about the Imperial household. This work is structured much like Yasukuniron, in that it unfolds the “truth” of the Emperor and Imperial Household for Japanese history, culture, and religion—with the intent of provoking within a sympathetic reader a “conversion” away from a mistaken and “dangerous” disregard to a healthy and informed embrace of the subject in question. The various chapters, interspersed with personal anecdotes and historical minutiae, tackle the issue from a wide variety of angles, albeit all coming to the same general conclusion: i.e., the Emperor and Imperial Household symbolize the historical and cultural essence of the Japanese people (kokumin) and Japan as a “national body” (here Kobayashi has no qualms about invoking the largely discredited term kokutai). In this last respect, against those who would criticize the Emperor for “elitism,” Kobayashi argues that, in fact, the Imperial line has always acted as an “empty vessel” representing the people, taking on, as it were, their sufferings and anxieties without complaint. Indeed, K argues, the Emperor in his unrelenting commitment to the people is ultimately “without personality” (mujikaku)—a notion graphically expressed by showing the Emperor in full sacred regalia, without a face (Figure 12).

[Figure 12] The “empty” Emperor, p. 37 |

[Figure 14] An invitation to collective Imperial “revisioning,” p. 379 |

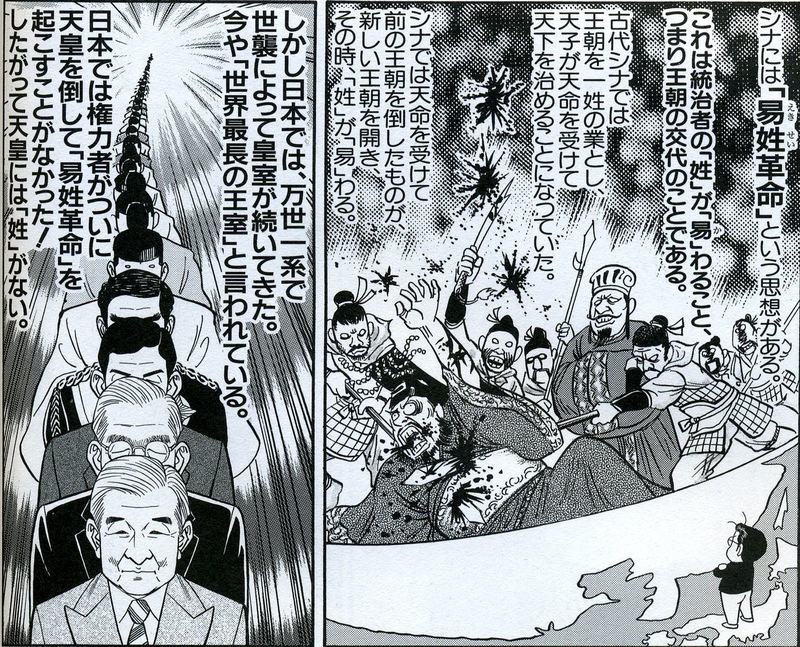

As with Yasukuniron, an explicit contrast is made with China.32 Whereas Chinese imperial history is rooted in a perpetual series of violent dynastic changes (see Figure 13), in which elites asserted their own claims to power while mercilessly slaughtering those who they intend to replace, Japanese imperial history has been peaceful, by virtue of have the “world’s oldest” continual dynastic succession.33 In short, the Chinese imperial system was rooted in the desire for power and materialistic gain, whereas the Japanese imperial system was born out of precisely the opposite feeling; i.e., the desire to protect and preserve the people. Of course, scholars have questioned the idea of an unbroken Yamato line for decades, but here, as usual, Kobayashi is making a point based on a “fact” accepted by most Japanese, and repeated in Japanese textbooks and standard histories.

Declaration of Humanity?

Most interesting with regard to the present essay, however, is the way that Kobayashi frames the Emperor in relation to religion—and specifically the notion that, immediately after the Second World War, the Imperial Household was forced to renounce in perpetuity its former “status” as a “god” (kami). This issue is dealt with in some detail in chapter nine: “Was the Emperor a ‘God’?” (“Tenno wa ‘kami’ datta no ka?”). As usual, K begins with an anecdote, in which he laments the fact that so many Japanese have bought into the notion that, prior to the so-called “Humanity Declaration” (ningen sengen) in January 1946, the Emperor believed himself and was believed by the populace to be a “god”—and that this was a cause for the war. It is not true, he avers, that people prior to and during the war thought of the Emperor as a god, though some did believe that he was a person who should be treated as if he were a god(“kami no yo ni taisetsu ni shinakereba ikenai hito”).34

Here K makes the interesting (and plausible) argument that those postwar commentators who have been so insistent on the idea that prewar Japanese held the Emperor to be a god are largely if not entirely of the generation that was raised on strict nationalist education (i.e., those who were exposed to school textbooks from 1939–1945), only to face a sudden, dramatic (and traumatic) change in what they were being taught in the occupation period, which caused them to flip to the other extreme in the postwar period.35 What was taught during this brief period, K argues, deviates from the ancient texts Kojiki and Nihon shoki, which make clear that, while the imperial line is descended from the gods, the “first Emperor” Jimmu was in fact a human being, not a kami—at least not in the same sense as the heavenly kami. Moreover, continuing the populist theme we saw in Yasukuniron, this is true not only for the imperial line but for all Japanese, who are said to be the descendents of kami, but not kami themselves. Thus, K concludes, the Emperor is the “head” (shuka) of the “national family” (kazoku kokka) rather than a being of a different species entirely.36 To his credit, Kobayashi admits that the ultranationalist ideal of the Emperor as a “god” was a modern construction—though he places the blame not on the late Taisho and early Showa ideologues who developed the idea but rather on the spread of communism in the wake of the First World War, which “forced” them to come up with a more potent nationalist ideology.37 Indeed, this half-decade “deviation” was perfectly understandable given the tremendous anxieties and pressures the nation faced.38 In short, K concludes, in the words of the Showa Emperor himself: “The Emperor is the supreme organ (saiko kikan) of the national body (kokutai)”.39

And yet, though the Emperor may not be a “god” in the Western (or Chinese) sense, he is certainly a very special person, one who deserves treatment “as if a god” by virtue of his status as the “supreme organ of the national body.” Just as with Yasukuni, in a strong sense the Emperor is the people. K develops this argument in the succeeding chapter: “The Emperor is a kami!” (“Tenno wa ‘kami’ de aru!”). After beginning by correctly pointing out that the traditional Japanese term kami never implied an omnipotent creator being along the lines of the monotheistic “God,” K, borrowing from Edo-period National Learning scholar Motoori Norinaga, notes that kami is better understood as a term denoting a measure of auspiciousness, and is frequently applied to human beings, even today (such as Tezuka Osamu, the “kami of manga”). And yet, Japanese people themselves do not always understand this distinction, due in large part to the linguistic confusion caused by the fact that the Sino-Japanese character 神 is employed for Chinese shin as well as the Abrahamic “God.”40 Unsurprisingly, this confusion was passed on to the American occupation leaders, who thus forced the Emperor to “renounce” his divinity—which ironically served to perpetuate the myth of prewar Imperial divinity.

In addition to—or rather as one aspect of—his status as the “supreme organ” of the kokutai, the Emperor functions as the “chief priest” (saishio) of the kami, in that he is the vehicle for transmission of the “spirit of benevolence” from the heavens to the earth. K notes that this is not the “superficial concept” of any particular Emperor being an individual of elevated moral character, but rather a function of the Emperor’s status as an akitsumikami, which he glosses as vehicle for the transmission of spiritual power.41 Indeed, K admits that there have been at least a few emperors that have not lived up to the standards of virtue or benevolence, a fact duly noted in the ancient texts themselves. But this actually helps him make his point that “virtue is not a condition for the position of Emperor”—if it were, it would only be used by power-hungry elites as an excuse for dynastic change (as in China). And yet, it so happens that the two thousand-year tradition of separation of “authority” (ken’i) and “power” (kenryoku) allows the Emperor to use the imperial throne as a conduit for the construction of benevolence.42 Ultimately, K argues, although not a “god” in the Western sense, the Japanese Tenno falls into a unique category, one that does not exist in any other nation or culture.43 “The Emperor, who holds authority (gen’i) without an ‘I’, is a public being (ko no sonzai) whose work is to pray for the people (min).”44

[Figure 13] Japanese vs. Chinese Imperial histories, p. 82 |

In short, although the Emperor is virtually absent from Kobayashi’s treatment of Yasukuni Shrine, Tennoron makes it clear that, in fact, the Imperial line functions in exactly the same way as Yasukuni; i.e., as an “empty vessel” that: a) preserves the essence of the Japanese spirit (in particular, the spirit of benevolence) and b) is willing and able to take on the burdens of the people, but consequently c) must be protected from external and internal foes, in order to d) ensure the survival of “Japan” and the “Japanese” (which are ultimately one and the same). Of course, one cannot actually “enter into” the Emperor in the way that one can and should “enter into” Yasukuni, but the basic principle outlined above still applies: an emotionally-charged focus on the Emperor/Yasukuni—an exchange of glances—will go a long way towards fulfilling the goal of personal-cum-national reconstruction (see Figure 14). “It is through the Emperor,” K forcefully reminds us, that “we [Japanese] are able to see our own sanctuary.”45

Conclusions

Although State Shinto was officially “disestablished” after the war, and has, along with ultra-nationalism and militarism, come to be repudiated by the vast majority of the Japanese people, the institutionalized form of Shinto as embodied in the postwar Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honcho) contains more than a few hints of its more obviously politicized forerunner.46 This is most clear in the promotion (and widely accepted notion) of Shinto as a cultural (if not “ethnic”) form that is somehow inherent to being “Japanese” (a belief that often goes hand-in-hand with a reluctance to label Shinto a “religion”). Indeed, Shinto-consciousness—or, since the word “Shinto” itself is not commonly employed in Japanese, kami, jinja, or matsuri-consciousness—plays a significant role in contemporary Japanese national identity, though only when reframed in terms that make it appear “cultural” rather than religious or political.47 Explicitly anti-political and anti-religious, this “folkism” or ethno-nationalism (minzokushugi) as a general pattern of thought remains strong in contemporary Japan, and can be readily tapped into by those whose aims are in fact political.48

Recommended citation: James Mark Shields, “Revisioning a Japanese Spiritual Recovery through Manga: Yasukuni and the Aesthetics and Ideology of Kobayashi Yoshinori’s “Gomanism”,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 47, No. 7, November 25, 2013.

Related articles

• John Breen, Popes, Bishops and War Criminals: reflections on Catholics and Yasukuni in post-war Japan

• John Junkerman, Li Ying’s “Yasukuni”: The Controversy Continues

• Yasukuni: The Stage for Memory and Oblivion. A Dialogue between Li Ying and Sai Yoichi

• Akiko Takenaka, Enshrinement Politics: War Dead and War Criminals at Yasukuni Shrine

•Takahashi Tetsuya, Yasukuni Shrine at the Heart of Japan’s National Debate: History, Memory, Denial

•Takahashi Tetsuya, The National Politics of the Yasukuni Shrine

•Utsumi Aiko, Yasukuni Shrine Imposes Silence on Bereaved Families

•Mark Selden, Japan, the United States, and Yasukuni Nationalism: War, Historical Memory, and the Future of the Asia-Pacific

•Matthew Penney, Nationalism and Anti-Americanism in Japan – Manga Wars, Aso, Tamogami, and Progressive Alternatives

•John Breen, Yasukuni Shrine: Ritual and Memory

•Yomiuri Shimbun and Asahi Shimbun, Yasukuni Shrine, Nationalism and Japan’s International Relations

•Andrew M. McGreevy, Arlington National Cemetery and Yasukuni Jinja: History, Memory, and the Sacred

Notes

- Parts of this essay have been previously published under the title: “‘Land of Kami, Land of the Dead’: Paligenesis and the Aesthetics of Religious Revisionism in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Neo-Gomanist Manifesto: On Yasukuni,” in Manga and the Representation of Japanese History, edited by Roman Rosenbaum, pp. 189–216. London: Routledge, 2012. Special thanks to Routledge for permission to republish this chapter in its present, significantly revised form.

- Kobayashi Yoshinori, Shin gomanizumu sengen special: Yasukuniron. Tokyo: Gentosha, 2005, p. 12. All manga images that appear in this essay are “quoted” for purposes of analysis; all copyrights are held by the original artist and publishers.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Ibid.; these facts (save the mention of the Britons) are all noted in the “overnote” to page 7.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- As Sharon Kinsella notes, “neo-conservative” seinen manga as a whole tend to rely on a realistic and objective narrative that effectively masks their ideological content; Sharon Kinsella, Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2000, pp. 112–113. While this applies to Kobayashi, who relies heavily on realistic (as well as photographic) images, it is important to note that Gomanism also employs caricature (Figures 4 and 5) and symbolism (Figure 6), as well as a form of kitschy sentimentalism that verges on “fantasy” (Figure 2). Also, whereas Kinsella critiques neo-conservative manga for (deceptively) striving to eliminate the authorial function, this would be hard to apply to Kobayashi, who fairly revels in making himself (as K) the hero of his own works.

- Kobayashi, Yasukuniron, p. 12.

- Throughout Yasukuniron, and the Gomanist oeuvre more generally, Kobayashi paints a portrait of himself as an astute, angry, but otherwise ordinary middle-aged everyman.

- To Kobayashi’s credit, he does not, like many commentators, avoid the trickier religious aspects of the Yasukuni problem; indeed, these become a centerpiece for his argument about the “criminal ignorance” (hanzaiteki muchi) of politicians, scholars and the mass media. Of course, much of what he says is either incorrect or grossly oversimplified.

- Ibid., p. 6, emphasis in original.

- See Matsumoto Ken’ichi, Mikuriya Takashi and Sakamoto Kazuya, “War Responsibility and Yasukuni Shrine,” Japan Echo 32:5, 2005, p. 26.

- Quoted in Takahashi Tetsuya, Yasukuni mondai. Tokyo: Chikuma Shinsho, 2005, p. 74.

- Kobayashi, Yasukuniron, p. 89.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Ibid., pp. 13–14.

- As shown by Takahashi Tetsuya, this way of thinking about the Japanese—as a single “we” that has lost its prior unity—continues to play a role in shaping debates about history and culture. Takahashi takes critic Kato Norihiro to task for extending this “nationalist” assumption, even while presenting himself as a “moderate.” Unsurprisingly, Kobayashi has attacked Kato from the other direction, accusing him of a “masochistic” approach to history (an accusation which is also applied to Takahashi’s own Yasukuni mondai, mentioned several times within the pages of Yasukuniron); see Takahashi, Yasukuni mondai, pp. 194–197.

- Prior to his “official” visit to Yasukuni on 15 August 1985, Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro explained that he would not follow the “traditional” Shinto practice of two bows, two claps, and one bow but would simply make a single bow before the honden. According to K, in thus bowing to left-wing media pressure, Nakasone inaugurated the sad legacy of the Prime Minister’s “private” vs. “public” visits to Yasukuni; Kobayashi, Yasukuniron, pp.32–35.

- Ibid., pp. 15–22.

- Ibid., pp. 16–19.

- Ibid., p. 21.

- The idea of misunderstandings of Yasukuni based on cultural differences regarding the afterlife, particularly with respect to Chinese versus Japanese views of death, is fairly common. Prime Minister Koizumi and Foreign Minister Machimura Nobutaka both raised the same point in response to foreign criticism of Koizumi’s 2004 visit to Yasukuni; see Takahashi, Yasukuni mondai, pp. 152–153.

- See Klaus Antoni, “Yasukuni-Jinja and Folk Religion: The Problem of Vengeful Spirits.” Asian Folklore Studies 47, 1988, p. 133; also Takahashi, Yasukuni mondai, pp. 58–59.

- See, e.g., Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanee History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- I have borrowed this term from Takahashi Tetsuya; see Takahashi Tetsuya, “Japanese Neo-Nationalism: A Critique of Kato Norihiro’s ‘After the Defeat’ Discourse,” in R. Calichman, ed., Contemporary Japanese Thought. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, p. 205.

- Roger Griffin, Roger, The Nature of Fascism. London: Pinter, 1991, p. xi.

- Kobayashi, Yasukuniron, p. 146.

- See Nelly Naumann, “The State Cult of the Nara and Early Heian Periods,” in J. Breen and M. Teeuwen, eds, Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. London: Routledge, 2000, pp. 54–55.

- The notion of death as “pollution” (kegare)—as one finds, for example, in the Kojiki—seems worlds away from Yasukuni theology, which is premised on death (for the emperor/state) as the highest act of nobility; indeed, as a virtual act of transcendence. And yet, even after the Restoration, Hirata School loyalists within the newly reconstituted Jingikanwere appalled by the Okuni faction’s support for “Shinto funerals”; see Helen Hardacre, Shintō and the State, 1868–1988. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 36.

- Brian Bocking, “Changing Images of Shinto: Sanja Takusen or the Three Oracles,” in J. Breen and M. Teeuwen, eds, Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. London: Routledge, 2000, pp. 167–185.

- The exception is several panels on page 177, in which K “rebuts” the misunderstanding about the emperor as a living “god,” and points out (fancifully; see Tim Barrett, “Shinto and Taoism in Early Japan,” in J. Breen and M. Teeuwen, eds, Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. London: Routledge, 2000, pp. 13–31) that the term tenno was deliberately chosen to make the Japanese emperor equivalent to the Chinese emperor, thus asserting Japan’s “independence” from the Middle Kingdom. Of note here is K’s reference to the Kojiki and Nihonshoki as “fables” (monogatari) that the Japanese people have the “magnanimity” (doryo) to hold onto, despite their “marvelous” (kisekiteki) character. This is another reflection of the modernist character of Kobayashi’s work.

- Of course, “empty,” as any East Asian Buddhist would know, need not imply powerless or ineffective; see Takashi Fujitani, Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996, p. 24.

- See especially chapter 17 of Tennoron: “Shina no odo, Nihon no nodo,” pp. 277–300.

- In chapter 17, K blames the bloody legacy of Chinese imperial history on the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven as established by Mencius, according to which “Heaven” (Ch. Tian) grants favor upon a particular Emperor—and can remove that favor if and when he is not acting with “benevolence.” This, K rightly notes, was frequently employed as a justification for “regime change,” and was not an idea that found favor in the transmission of Confucianism to ancient Japan.

- Kobayashi, Tennoron, p. 154.

- Ibid., pp. 154–57.

- Ibid., p. 160.

- Ibid., p. 161.

- Ibid., p. 164.

- Ibid., p. 168.

- Ibid., p. 170.

- Ibid., p. 173.

- Ibid., p. 186.

- Ibid., p. 37.

- Ibid., p. 195.

- Ibid., p. 186.

- See Murakami Shigeyoshi, Kokka Shinto. Tokyo: Iwanami Shinsho, 1970, pp. 216–222; also see the Jinja Honcho website: http:// www.jinjahoncho.or.jp/, accessed 12 July 2012. Thanks to John Breen for bringing to my attention the different portrayals of Shinto on the English and Japanese versions of the website.

- See Nishikawa Nagao, “Two Interpretations of Japanese Culture,” in D. Denoon, M. Hudson, G. McCormack and T. Morris-Suzuki, eds, Multicultural Japan: Palaeolithic to Postmodern. London: Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 248. Also see Takahashi’s critique of Eto’s use of “culture” (bunka) to mask Yasukuni’s political agenda; Takahashi, Yasukuni mondai, pp. 173–178.

- See Kevin Doak’s argument with respect to a postwar continuation of “fascism unseen”; Kevin M. Doak, “Fascism Seen and Unseen: Fascism as a Problem in Cultural Representation,” in A. Tansman, ed., The Culture of Japanese Fascism. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2009, pp. 33–34.