Introduction

From the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45 to the Communist Revolution of 1949, the onrushing narrative of modern China can drown out the stories of the people who lived it. Yet a remarkable cache of letters from one of China’s most prominent and influential families, the Lius of Shanghai, sheds new light on this tumultuous era. These letters take us inside the Lius’ world to explore how the family laid the foundation for a business dynasty before the war and then confronted the challenges of war, civil unrest, and social upheaval.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the Lius became one of China’s preeminent business families, presiding over an industrial empire that produced matches, woolens, cotton textiles, cement, and briquettes.

|

The Lius’ Match Factory in Shanghai, 1935 (Courtesy of Guoji Maoyi Daobao) |

At the same time, the father and mother in the family prepared for the future by giving international educations to almost all of their twelve children – nine boys and three girls – sending them not only to schools in China but also to Cambridge University, Harvard Business School, University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology, and other leading institutions of higher learning in the West and Japan. Moreover the father and some of his sons became politically influential, accepting appointments to high official posts and dealing in person with top leaders such as Chiang Kai-shek in the Nationalist government and Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai in the People’s Republic. Even during two of the greatest upheavals in twentieth-century Chinese history – the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45 and the Communist Revolution of 1949 – the Lius retained high positions in China’s economic, social, and political life.

The Lius of Shanghai is based on a lifetime of letters exchanged by the patriarch, Liu Hongsheng, his wife, Ye Suzhen, and their twelve children. Their correspondence offers a fascinating look at how a powerful family navigated the treacherous politics of the period. They discuss sensitive issues—should the family collaborate with the Japanese occupiers? should it flee after the communist takeover?—as well as intimate domestic matters like marital infidelity. They also describe the agonies of wartime separation, protracted battles for control of the family firm, and the parents’ struggle to maintain authority in the face of swiftly changing values. Through it all, the distinctive voices of the Lius shine through, revealing how each of them passionately engaged in family arguments, and at the same time held onto the ties that bound them together.

The book is divided into four parts to indicate how the Liu family’s debates varied in different historical contexts. Parts I and II are set in the late1920s and 1930s, a period of relative openness when Chinese traveled freely within and outside their country. During this time, the father’s business empire was expanding, and he seized opportunities to send his children abroad for their educations. He wanted them to learn how to operate throughout the capitalist world and succeed at perpetuating a multigenerational business dynasty based in China. His children set out from Shanghai on their educational ventures voluntarily and even enthusiastically, and once they settled into their schools and lives abroad, he and they argued about decisions with long-term implications, especially regarding their educations, careers, and choices of marriage partners.

|

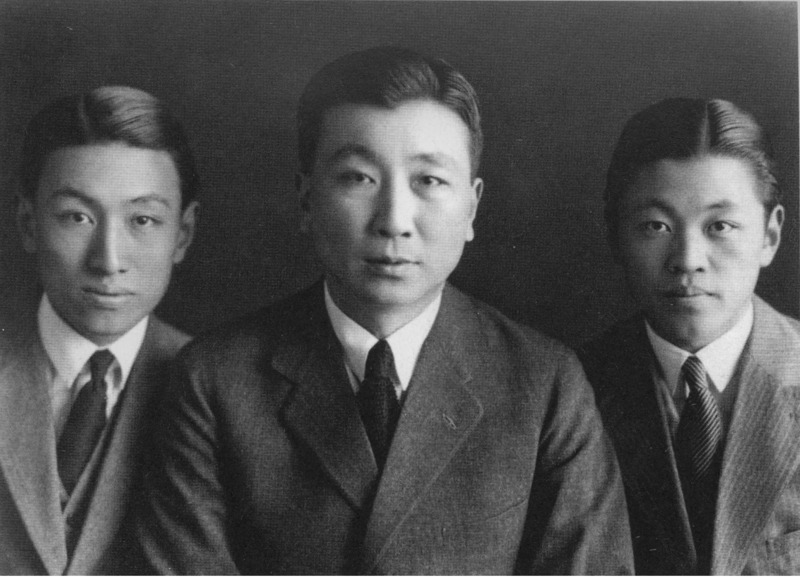

The eldest son, the father, and the second son at the beginning of the Sino-Japanese War shortly before the father fled from Shanghai leaving leadership of the family firm in the hands of these two young men, c. 1938. (Courtesy of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences) |

Part III is set in a very different historical context – a period when China was largely cut off from the West and torn apart by the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45. The war threw the Lius on the defensive. Quite contrary to their original plan, the father and some of his children involuntarily fled from Shanghai during the Japanese military invasion, leaving behind the mother and the rest of the children. Throughout the war, they discussed short-term strategies for survival more than long-term plans for the future. They continued to debate with each other over family matters such as marital discord, psychiatric breakdown, and business policies, but their debates became inextricably bound up with political issues: whether to cooperate with the Japanese forces that were occupying the Lius’ hometown of Shanghai and later Hong Kong; or align with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government and relocate to his wartime capital of Chongqing 900 miles west of Shanghai; or join the Communist movement under the leadership of Mao Zedong at its base in Yan’an 750 miles northwest of Shanghai.

Part IV shows that the Lius found themselves in another radically transformed historical context as a result of the Communist Revolution of 1949. In the wake of this event, some of the Lius argued with others in the family about whether they should stay in China, flee from it, or return home from abroad. In May 1949, when the People’s Liberation Army took over Shanghai, the father left behind his wife and most of his children and moved to the British colony of Hong Kong. Over the next six months he debated with them whether he should rejoin them (as they and emissaries sent by Zhou Enlai from Beijing urged him to do) or stay abroad (as his business associates in Hong Kong counseled). After he finally decided to go back to Shanghai, he then urged the last two of his children who were still receiving educations in the West to come back to China once they had completed their degrees. In the early 1950s, his exchanges with one of his sons on this subject turned into a Cold War debate over whether freedom had been lost in China since the Chinese Communist Party had assumed power there.

In all four parts of the book, the Lius’ letters are cited and quoted as primary sources to convey the intimacy of the family members’ exchanges as they dealt with their most pressing disagreements in the historical contexts of their times. The excerpt below is based on one series of these exchanges in which the father and his eldest sons debated how to manage the family firm under the Japanese occupation during the Sino-Japanese War.

Sons Who Became Leaders in Wartime

I N L AT E June 1938, a year after the Japanese military invasion of China, Father fled Shanghai. Pulling his hat down and his scarf up to cover his face, he slipped onto the Canadian ship Empress of Russia, bound for Hong Kong, 760 miles southwest of Shanghai, where he arrived June

30. He left behind in Shanghai his business, his wife, and most of his children. By then, he had lost control of parts of his business (his match mills, cement plant, enamel factory, and wharves) because these had been seized by the Japanese forces under their occupation of Shanghai. But he still retained control over a considerable amount of property (his eight-story headquarters building, bank, insurance firm, and real estate agency) because these were located in the British-dominated International Settlement, which the Japanese left untouched until December 1941—the time of Pearl Harbor and the beginning of the Pacific War against Britain, the United States, and other Western countries.

With his family and these assets in Shanghai, he had good personal and professional reasons to remain in his hometown.

|

The Lius’ Cement Works in Shanghai, c. 1930s.(Courtesy of Shanghai Tan) |

Father left his family and his family firm behind and fled Shanghai because he was afraid of being assassinated by combatants on both sides of the Sino-Japanese War. From the Japanese side, a military official named Ueda Jiichiro had personally threatened Father. In a series of four or five meetings with Father and Second and Fourth Sons during June, Ueda had offered Father the presidency of the Japanese-sponsored Shanghai Chamber of Commerce and ominously declared that if Father declined the offer, Ueda could not guarantee the safety of the Liu family. From the Chinese side, pro–Chiang Kai-shek agents had

posed a less direct but equally dangerous threat to Father because they had already begun assassinating Chinese for accepting Japanese offers of posts exactly like this one. Caught in a crossfire, Father feared putting his family and himself in harm’s way whether he accepted or declined Ueda’s offer, so he avoided the issue by fleeing to the British colony of Hong Kong, which the Japanese refrained from invading between 1937 and 1941.

When the war forced Father to leave Shanghai, it marked a key turning point in the history of the Liu family. As he left, he expressed the hope that he would soon return. Contrary to his hopes, he did not come back until the end of the long war in 1945, seven years later. He did not leave the family entirely headless, because he tried to maintain his authority over it from a distance by regularly writing letters and periodically arranging for family members to visit and work with him. But his long absence had profound effects on decision making in the Liu family. During this time he was no longer available to provide face-to-face consultation and supervision in Shanghai, leaving far more responsibility for decision making in the hands of his wife and children there.

In the family firm, his four eldest sons were directly affected by his absence because they were catapulted into top executive positions. Before the war Father had warned them that they would need to spend several years learning about the business and working their way up the managerial ladder. In the wartime emergency, he waived this requirement and excused them from making further preparations. Though the four eldest sons were all still in their twenties, he gave them full responsibility for presiding over the family firm. He recognized that their youthfulness would spare them from the dilemma that drove him out of Shanghai because the Japanese authorities would never appoint such young men to high official positions under the occupation. But with their lack of experience, would his sons make sound business decisions, and in his absence, would they follow his orders? These questions arose as Father delegated authority to them, and each son seized the opportunity to take the initiative in his assigned sector of the family firm.

Eldest Son and Finance in Shanghai

After fleeing, Father recognized that his life was at risk, and while not relinquishing his authority over the family firm, he took steps to shift it all into his sons’ hands in the event of his death. Within a week of his arrival in Hong Kong, he sent his sons in Shanghai legal documents that would, if necessary, grant them power of attorney. As he wrote in a cover note to Eldest Son and his other sons on July 6, 1938, “I have signed 12 copies of powers of attorney & witnessed by 2 friends. I did it simply against any emergency. Nobody can be too careful. Please keep them locked & only use them when it is necessary.” Although straight-forward and matter-of-fact, Father’s handwritten note was a grim reminder that “any emergency” might well include an attempt to assassinate him. Even if he were to die, he believed that the family firm would live on because his sons had become mature adults and potential leaders. As he wrote from Hong Kong to Fourth Son in Shanghai on September 24: “I have grown up sons, whose minds have developed & matured, therefore I am always ready to take your opinions into consideration. In fact I have more faith in you boys than anybody else including myself.”

If, as he claimed, Father really did have greater faith in his sons than himself, this faith was severely tested during the war. Within the first year after Father had fled to Hong Kong, he clashed with Eldest Son over the handling of the family firm’s finances in Shanghai. In May 1937, just two years after Eldest Son had returned from his studies at Harvard and University of Pennsylvania and only a few months before the war broke out, Father had appointed Eldest Son as the general overseer and head of Liu Hong Ji, the family’s accounts office. In Eldest Son’s first year at this post, Father had closely supervised him both in person and indirectly through senior managers whom Father assigned to work with him.6 But after Father left for Hong Kong, Eldest Son did not heed his warnings or follow his senior managers’ advice as closely as he had when Father was in Shanghai. Instead, he began appropriating funds from Liu Hong Ji for real estate speculation and making decisions on his own.

When Eldest Son first neglected to consult Father about financial decisions, Father tried to reason with him. In April 1939, less than a year after Father had left Shanghai, he became annoyed with Eldest Son for putting the Liu family home up for sale without mentioning it to him, and he mildly chastised him and his brothers for it. Explaining to them that he had learned what they had done from the buyer, whom he had met by chance on a business trip, Father wrote from Hong Kong

to his sons in Shanghai on April 23: “I didn’t have any idea of this until he told me this time. I hope you can let me know of things like this next time before they are put into effect.”8 But Eldest Son and his brothers did not take this admonition to heart.

In June, Eldest Son made another financial decision without considering advice from Father and the business’s senior managers, and this time Father lost his temper. Eldest Son made the mistake of keeping Liu Hong Ji’s funds largely in Chinese currency and buying only US$10,000 in foreign currency just before the value of Chinese currency suddenly dropped. Other senior managers of the family’s businesses, notably Xu Shihao, a lawyer and accountant at the Lius’ Great China Match Company in Shanghai, had followed Father’s orders to buy large amounts of foreign currency and had made substantial financial gains as a result of its rising value in relation to the fall in the value of Chinese currency. But Eldest Son and his brothers had gone their own way, bought too little foreign currency, and suffered heavy losses.

When Father learned that his sons had ignored his advice on currency exchange, he came down hard on them. Barely containing his anger, he reminded them that he had deliberately loosened their leash and allowed them to play a greater role in the decision-making process in Shanghai during his year in Hong Kong. Now, he declared, he would no longer grant them such latitude. “You are aware,” he wrote to his sons on June 25, “that in spite of the complexities in the affairs of my various companies in Shanghai, all along I have been endeavoring to keep things as quiet as possible, at least on the surface, by [the] method of compromise. Circumstances have convinced me however that I have now to take a more firm attitude.”

In these unequivocal words, Father ordered Eldest Son and his other sons to relinquish their authority over financial decision making to Xu Shihao. “Whatever development may come in future,” Father told them, “Mr. Hsu [Xu] will have full power to deal with it as he likes.” His sons, by contrast, were to play a strictly subordinate role. “I cannot emphasize to you too strongly,” Father told them, “that in all matters you should listen to his advice and not be too independent and do things on your own account. It is my wish that in case of any difference in opinions Mr. Hsu’s views shall prevail.”

Father made clear that he did not want Eldest Son and his other sons to become too independent until they had acquired more experience. “While you boys may be of some assistance to him in his work, you must bear in mind that in many respects you are as yet still entirely inexperienced.” In Father’s absence, all of his sons—even Eldest Son, who had held a high position longest—should conduct the business not on their own but under the tutelage of his senior business associates, like Xu.

In light of their financial losses, Eldest Son and his brothers could not deny that they had failed in this case. In fact, Third Son admitted in a letter to his brothers that Father was right about the mistakes they had made. At the time of Father’s tirade against them, Third Son was working with him in Hong Kong, and after hearing Father’s complaints in person, he conveyed them to his brothers in Shanghai. “This time,” he wrote, implicitly reminding them that it was not the first time, “Father is really justified in making his complaint as he has been asking us to buy foreign currency all the time and we did not carry out his instructions. From now on I hope you will read his letters carefully and give a little thought to his instructions.”

In making this criticism and recommendation, Third Son took his share of the blame, acknowledging that he, along with his brothers, had been wrong not to take Father’s advice seriously. “Please,” he told them, “do not think that I am shifting the blame on you. In fact I was in Shanghai myself at the time when his letters came and consider myself equally responsible. I think the practice of passing father’s letters along is not very good. Next time if he gives any specific instructions we must,” he emphasized, “consider what action we should take.”

But even as Third Son took the blame in this case and proposed to his brothers that they should be more attentive in the future, it is notable that he assumed that he, Eldest Son, and his other brothers would continue to hold ultimate decision-making authority in their own hands, as he implied in saying that they would be the ones to “consider what action we should take.” Despite the bad outcome in this one case in 1939, Third Son and his brothers had no intention of relinquishing their newly acquired authority in the family business at Shanghai for the foreseeable future.

These exchanges between Father in Hong Kong and Eldest Son and his brothers in Shanghai underscore the difficulty in wartime China of managing a business from a remote location. On the surface, it might appear that from his new base in Hong Kong Father could have easily managed his finances in Shanghai simply by relying on Eldest Son to do his bidding. In fact, Father could not exercise authority or supervise his sons as closely as he had done face-to-face in prewar Shanghai. Marooned in Hong Kong as an absentee father and manager, he had a difficult time persuading his sons to take his advice or even give him their attention. In Shanghai he had left a leadership vacuum, and his sons readily filled it.

Second Son and Industry in Shanghai

Just as Eldest Son took new authority over the Lius’ finances, Second son took new authority over their biggest industrial enterprise. In June 1938, when Father refused to collaborate with the Japanese and fled Shanghai, he resigned as general manager of his biggest industrial enterprise, Great China Match Company, and left Second Son in charge of it. For the next two years, Second Son did not have official authority over the company because it was located in Zhabei, a district of Shanghai under Japanese occupation, and the Japanese military authorities designated it “enemy property” and seized control. In May 1940, Second Son and the other members of Great China Match’s board of directors were notified that they might be able to regain control of the company if they would cooperate with a new Chinese regime that had been founded with Japanese approval under Wang Jingwei, a former member of Chiang Kai-shek’s government. Intrigued by this possibility, Second Son tried to talk Father into pursuing it.

In the summer of 1940, Second Son traveled to Hong Kong and had a series of meetings with Father face-to-face to present his proposal for regaining control of Great China Match Company in Shanghai by cooperating with Wang Jingwei’s collaborationist government. By then, Second Son no longer espoused ardent anti-Japanese nationalism as he had done during the Shanghai Incident of 1932, when he and his brothers had rejected Father’s proposal that they become British citizens. But in 1940, after returning to Shanghai, assuming a position of authority in the family business, and living under Japanese rule, Second Son was frustrated to discover that Father was more nationalistic than he was.

On his visit, Second Son was unable to talk Father into approving his ideas for cooperation with the Japanese, and he accused Father of allowing a nationalistic political bias to cloud his judgment as a businessman. On August 5, as he prepared to return to Shanghai after spending a month with Father, he vented his frustration. “While I had no intention of driving into your mind the wisdom of your early return to Shanghai,” he wrote to Father, “I must confess that your view on this matter has been a very great disappointment to me. While you are considering political complications of your return I stick 100% to business and industry.” By sticking strictly to business and industry, Second Son felt that he had set well-defined goals that were free of nationalism and other ideologies.

Second Son considered his own position pragmatic and flexible, and he complained that Father was being politically rigid. Confronting Father more directly by letter than he had allowed himself to do in person, he wrote: “I have found your own views so often totally contradictory that I completely gave up the idea of any personal persuasion on my part. It has been difficult for me as a son to express my inner feelings so I have deliberately avoided discussing this matter [with] you too often. I shall go back to Shanghai with renewed courage though somewhat puzzled and disappointed.”

Second Son was disappointed not only with Father but with the other émigré Shanghai business people who, in his estimation, were wasting their time remaining idle in Hong Kong merely for the sake of fleeing from the Japanese occupation rather than returning home now that they had the opportunity to regain control of their businesses under Japanese or Japanese-sponsored Chinese governments. “I can now only laugh,” he wrote sardonically to Father. “We are now in the process of making a great decision. We all take our respective chances. It puzzles me how so many big shots in Hong Kong can solve their dilemma by staying on and remaining inactive there.” He was unable to fathom why any Shanghai businessman would choose to waste time this way in Hong Kong.

Back in Shanghai, he tried to outmaneuver the Japanese controllers at Great China Match Company. “As the Japanese control over our company gets tighter and tighter, we have resorted to keeping a second set of books,” he wrote to Father on November 6. “So far, they haven’t been to our company to check our books.” Besides hiding financial records in a secret set of books, Second Son searched for other ways to keep funds out of the Japanese controllers’ hands. “I have been in close touch with our attorney about possible ways of protecting our money,” he wrote to Father. Under his management, this money had increased, he reported to Father on December 28. “The future of Great China Match Company is difficult to predict, but it is now doing quite well. Profit for this year will be 2,000,000 yuan. Please keep this a secret.”

Second Son took pride in his success at not merely preserving Great China Match Company but making it profitable under the Japanese occupation during his first years in charge, 1938–1940. Under Japanese restrictions, he could not take profits, give bonuses, or distribute dividends at the company, but he believed that he could overcome these restrictions if only Father would allow him to cooperate with Wang Jingwei’s government and the Japanese authorities in Shanghai. While Second Son favored this policy of cooperation, he could not pursue it without Father’s approval, which he was not likely to receive unless he won the support of others in the family not only in Shanghai but also in Hong Kong.

Third Son and Industry in Hong Kong

In the first years after Father’s flight from Shanghai in 1938, Third Son worked with him more closely than any of his other sons did. In 1939, at Father’s request, Third Son and his young bride, Liane, joined Father in Hong Kong, and in 1940 he became the manager of a new venture Father had founded, Great China Match Company of Hong Kong. Between the Lius’ registration of the company in June 1940 and the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in December 1941, Third Son made a promising start with the new business. Initially capitalized at HK$300,000, it earned between HK$500,000 and HK$600,000 in 1940 and 1941. In these years, Third Son was pleased to be working with Father and supporting the family firm through the new branch in Hong Kong, and he fully aligned himself with Father’s policies for Shanghai as well as Hong Kong. Before the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, he became the intermediary for conveying Father’s views— including his criticisms—to the rest of the family in Shanghai.

After hearing Father grumble about his sons’ lack of cooperation in Shanghai, Third Son told them that he thought this criticism was valid. “Now that I have been away,” he wrote from his post in Hong Kong to his brothers in Shanghai on July 22, 1941, “I can see more clearly the necessity of cooperation among us brothers more than ever. Unless we work hard and cooperate smoothly we shall not stand a chance against others.” They needed to cooperate, he pointed out to them, to justify Father’s decision to delegate authority to them during the war. “There must be perfect cooperation and understanding among us brothers before we can expect Father to have faith in us. He will simply say how can you expect to get on well with other people if you cannot get on well with each other.” If they were cooperating perfectly, Third Son implied, Second Son and the others in Shanghai would undeviatingly follow Father’s orders as Third Son himself was doing in Hong Kong.

He also passed along Father’s criticism of them for not working hard. “We must show complete devotion to our work before we can expect Father to look on us with approval,” Third Son told them. Father “has the impression that we are all having an easy and comfortable time in Shanghai and ought to work much harder,” and, Third Son had to admit, he had the same impression. “When I think that in Shanghai everybody leaves the office at 4 P.M. this is really not hard enough work for young men.” In Hong Kong, Third Son himself put in much longer days. “Without any exaggeration, I now work from 9 A.M. to 1 P.M. and from 2 to 6 or 7 P.M.” He added: “Father works even harder.”

Failing to rise to Father’s standards would cause the brothers to suffer in the long run, Third Son warned them. Even if Father had been forced to elevate them to high positions because of the war, they would be wrong to assume that he would pardon them or make exceptions for them merely because they were his sons. Third Son admitted that Chinese businessmen commonly practiced nepotism, but he reminded his brothers that Father did not. “There are two schools of thought among the leading businessmen of China. One will trust blindly everything in the hands of members of the family and relatives. The other will go out of his way to prove his fairness by not allowing members and relatives of the family to hold key posts unless they have really proved their worth. The latter school is comparatively rare, but our father belongs to that school.”

As an opponent of nepotism, Father would hold his sons to a high standard, and in Third Son’s estimation, even while Father was based outside Shanghai, he still retained the ultimate authority to determine all of the posts his sons would hold throughout the family firm. “I am telling you this,” Third Son wrote, “because I want you to realise that

we cannot expect father to lift us to any high post unless we can convince him of our ability to be able to do the job better than anyone else.” As Third Son envisioned the future in July 1941, five months before Japan’s invasion of Hong Kong, no matter where the family’s assets might be dispersed, Father would always have the authority to hire, promote, and fire the family firm’s managers.

Up to this point in the war, Third Son was aligned with Father and against his brothers, but after Japan’s invasion of Hong Kong in December 1941, his sympathies began to shift. By then Father had established a residence in Chongqing and was paying fewer visits to Hong Kong, and when Third Son had to face the prospect of a Japanese takeover of Great China Match Company in Hong Kong, he began to identify less with his father and more with his brothers in Shanghai on the issue of whether to cooperate with the Japanese and Wang Jingwei’s Japanese-approved Chinese regime.

In June 1942, after living under the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong for six months, Japanese business associates representing Mitsui Company in Hong Kong approached Third Son. He listened to their proposals, and he began to reconsider Father’s wartime policy of dividing the family business between Shanghai and Hong Kong. “The Mitsui Company here,” he wrote to Eldest and Second Sons on June 22, “has repeatedly invited us to return to Shanghai to revive our old enterprises there.” He urged his brothers to take this proposal seriously, and he assumed that they would react favorably to it, as long as it was carefully carried out after “making sufficient preparations” to avoid “any rash decision so that we’ll have no regrets in the future.”

On the same day, Third Son sent Father a version of the same proposal and admitted in his cover letter that he was apprehensive about Father’s reaction to it. “We are afraid that you will not approve our request,” he wrote, “and then there will be a deadlock.” He pleaded with Father to consider the proposal carefully, give approval, and avoid a deadlock because the time was right for a change in the family’s policy. Third Son warned Father that if the Lius did not accept the Japanese invitation to move from Hong Kong back to Shanghai and form new Sino-Japanese joint ventures immediately, they would miss their chance. Referring to conversations with his Japanese business associates at Mitsui, he wrote: “Now that they have already shown an interest in us, it would be easy for us to push the boat in the direction that the current is flowing. If we don’t accept, they will certainly find others [who would take advantage of the Japanese invitation to cooperate]. After they succeed in finding others, it will be impossible for us to put our hand in.” With a sense of urgency, he told Father: “Time is not on our side, and the opportunity mustn’t be lost. It is apparent that we should carefully consider this matter from all sides and come to a decision soon.”

While calling for action in the immediate present, Third Son noted the long-term significance of this decision for the future. He predicted: “There are only two possible outcomes in the future. Either A [Japan] wins, and if that’s the case, our making a move now will not cause any problems. Or B [the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek] wins, and as it’s now going, that won’t happen for several years.” In case the Japanese won, the Lius should begin cooperating with them as soon as possible. Even if the Nationalists were to win, it would take so long for them to do so that the Liu family would not benefit from having allied with them. “By then,” Third Son lamented to Father, “it would be impossible for us even to begin a revival of our business.” So the Lius should accept the invitation to cooperate with the Japanese in either case.

Anticipating Father’s political objection to this plan, Third Son addressed the question whether it was unpatriotic. He dismissed as hypocrites those Shanghai business people currently based in Hong Kong who now claimed that they refused to form Sino-Japanese joint ventures in Shanghai because of their patriotic principles. “Those big shots owning property in Hong Kong and Shanghai may sing sweet melodies to please the ears in public,” he told Father, “but in private they are doing everything in their power to protect their enterprises.” Privately, if not publicly, these Shanghai capitalists had already set precedents for cooperating with the Japanese. “Many others have done so before us, and no one will criticize us for it.”

In resisting the temptation to collaborate with the Japanese, the Lius had held out longer and adopted a more principled position than any of the other Shanghai business people, Third Son maintained. “We have suffered great pain and made great sacrifices during the past five years,” he reminded Father in 1942. “We can honestly face Heaven in good conscience.” If one viewed their decision in strictly nationalistic terms, he admitted, the Lius faced a difficult choice “between the bad and the worse,” but he claimed that his proposal for cooperating with

the Japanese was not devoid of patriotic value. “Saving the enterprises,” he wrote to Father, “would mean preserving the national spirit.”

In June 1942 Third Son placed his proposal in the hands of a trusted business associate whom Father had sent from Chongqing to Hong Kong to serve as a personal envoy and courier. Third Son also sent a copy to his two eldest brothers in Shanghai and urged them to bring it to the attention of other members of the family and senior managers in the family firm. Confident that they would support the idea, he deferred to their judgment. “We have been away from Shanghai for a long time,” he wrote to Eldest and Second Sons in 1942, three years after he had left Shanghai and four years after Father had done so. “You brothers have been there, and what you have seen and heard must be closer to the truth.” Now fully aligned with his elder brothers in Shanghai, he did all that he could to win Father over to their side.

By the end of 1942, Third Son and his brothers in Shanghai finally had their way. On December 1, the Lius’ Great China Match Company and the Japanese Central China Match Company signed a formal agreement creating a joint venture. On paper the Chinese side held a majority of the stock, but the Japanese side, which was a subsidiary of a huge Japanese holding company known as the Central China Development Corporation, retained control over raw materials and sales of matches. Second Son served on the joint venture’s board of directors, and by giving it two of Great China Match’s plants, he became free to make use of profits from the firm’s other four operations in Shanghai.

While Third Son’s proposal for forming joint ventures in Shanghai was carried out, his plan for disposing of the family’s Hong Kong match company and moving back to Shanghai was not. The Lius retained ownership of it, and Third Son stayed on as its manager in Hong Kong. After the Japanese occupied Hong Kong, he kept control of it for eleven months, from December 1941 to November 1942, and when he lost control of it, he tried to regain it by petitioning Japanese officials not only in Hong Kong but also through his family’s contacts in Shanghai. He notified his uncle (Father’s brother) in Shanghai that the Japanese authorities in Hong Kong “strongly believe that our factory has hostile connections and have handed our case over to the enemy properties committee.” He explained that “hostile connections” meant “Chongqing colors”—loyalty to the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek,

whose wartime capital was in Chongqing. To exonerate the Hong Kong company from these charges, Third Son had his family members in Shanghai apply to the Wang Jingwei government for certificates indicating that he and Father “were merely merchants without any connection to hostile forces.”

With help from his family in Shanghai and his Japanese business associates in Hong Kong, Third Son regained control of Great China Match Company of Hong Kong in August 1943. His success at resuming control so quickly—only ten months after he had lost it—was attributable to his and his brothers’ improved relations with the Japanese authorities in Shanghai since they had formed their first Sino-Japanese joint venture in December 1942.

In retrospect, it is clear that Third Son preserved the family business in Hong Kong by following a precedent that had been set by Second Son in Shanghai. Second Son had initially joined with Father in rejecting the policy of cooperation with the Japanese in Shanghai in 1938 and 1939 and then had begun to urge Father to approve this policy beginning in 1940. Taking the same steps slightly later, Third Son initially joined with Father in rejecting the policy of cooperation with the Japanese in Hong Kong in 1940 and 1941 and then began to urge Father to approve this policy in 1942. Both sons came to the conclusion that only by adopting this policy could they regain control over the family business and keep it operating under the Japanese occupation.

Second Son and Third Son both had difficulty persuading Father that cooperation with the Japanese authorities and Wang Jingwei’s government would bring control over management, profits, dividends, and bonuses back into the family’s hands and would cause the family businesses in Shanghai and Hong Kong to prosper. He refused to adopt this policy while he resided in Shanghai in 1937–1938 and Hong Kong in 1938–1940, and he only acquiesced to it after he had left his sons in charge in those cities. Fleeing first from Shanghai to Hong Kong in 1938 and then from Hong Kong to Chongqing at the end of 1940, he was not physically present to preside over any of the family businesses in these cities under the Japanese occupation. But in Chongqing, which was never occupied by Japan, he did personally establish new enter- prises as part of the family business, and he recruited Fourth Son to help him there.

Excerpt from Sherman Cochran and Andrew Hsieh, The Lius of Shanghai, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013, pp. 165-177.

Sherman Cochran is Hu Shih Professor of History Emeritus at Cornell University. He and Andrew Hsieh are co-authors of The Lius of Shanghai, which was published earlier this year. Of Cochran’s previous books, the most recent is Chinese Medicine Men: Consumer Culture in China and Southeast Asia (2006).

Andrew Hsieh is Professor of History Emeritus at Grinnell College. He has been co-author with Sherman Cochran of not only The Lius of Shanghai but also an earlier book, One Day in China: May 21, 1936 (1983).

Recommended citation: Sherman Cochran and Andrew Hsieh, “The Lius of Shanghai: A Chinese Family in Business, War and Revolution,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 34, No. 2. August 19, 2013.