In Mongolia today, hunger for coal, copper, gold and uranium wealth is at odds with democracy as the demands of international resource giants collide with a stubborn political culture of resource nationalism.

In time for the June 2012 parliamentary elections, Mongolia’s grand khural passed a law subjecting the purchase by “state-owned entities” of controlling interest in strategic Mongolian mining enterprises to government approval (as well as a host of other key industries).

The immediate provocation for the legislation was the sale by a Canadian company, Ivanhoe Resources, of its controlling interest in SouthGobi, an operator of coal mines in Mongolia, to a Chinese resource giant, the Aluminum Company of China, known as Chalco.

The legislation overtly targeted China. Vice Finance Minister Ganhuyag Chuluun Hutagt told Bloomberg that the country needed new investment laws to diversity its exports to countries other than China, which consumes a lion’s share of Mongolia’s coal and copper:

We don’t want to be faced with one sovereign … Our struggle to gain political freedom was a long one and we cherish that. We will not let foreign government-owned entities control strategic assets in Mongolia.

This is not an unambiguous win for non-Chinese international resource companies.

|

After all, there are two ways to make money from ownership of a mining concession. One is to engage in the arduous, expensive, long-term and risky enterprise of operating the mine. Another is to sell it. And the people who are willing to pay top dollar for a mine are the people who are already buying the product and have a powerful economic incentive for making a go of it … like the Chinese. So the Mongolian government’s involvement in strategic industries can be looked at in two different ways. On the one hand, it might hobble a deep-pocketed, overweening competitor to the benefit of other, grateful players; on the other hand, it might be seen as increasing the risk and diminishing the liquidity of investments in the so-called strategic industries, shaving precious points off the value of the assets, be they hard rock or financial paper. Unsurprisingly, the investment community, which is politely slavering at the prospect of profitable deal flows from Mongolian mining initial public offerings (IPOs) and mergers and acquisitions, is not amused by the strategic industry law. Dale Choi, of the pre-eminent Mongolia resource investment firm Frontier Securities, told Bloomberg:

Investors don’t like it when the rules of the game are changed after the game has started, and changed often at that … It would be in the interests of Mongolian people to make a decision based on commercial factors, rather than geopolitical factors. 1

The uncertain progress of the Tavan Tolgoi project illustrates the headaches facing Mongolia as it tries to reap its resource bonanza on behalf of its citizens even as the remorseless economic logic of globalization demands marginalization of their interests. Tavan Tolgoi, in the Gobi Desert less than 300 kilometers from the Chinese border, contains over six billion tons of coal reserves, including 1.8 billion tons of coking coal, a premium and profitable item used in the iron and steel industry.

|

Tavan Tolgoi (Five Hill) |

Nothing about Tavan Tolgoi is simple, except perhaps the physical process of digging the coal out of the ground (albeit with the usual environmental and cultural trauma). Chalco is already buying all the coking coal that Tavan Tolgoi produces. But it has to truck the coal to China since the Mongolian government has dragged its feet on approving the 300-kilometer railway that would connect to the Chinese rail system, thereby making China the only feasible buyer. Mongolia’s current anxiety about Chinese domination of its international trade channels (China accounts for perhaps 80% of Mongolia’s export and import trade) is buttressed by significant historical and political factors.

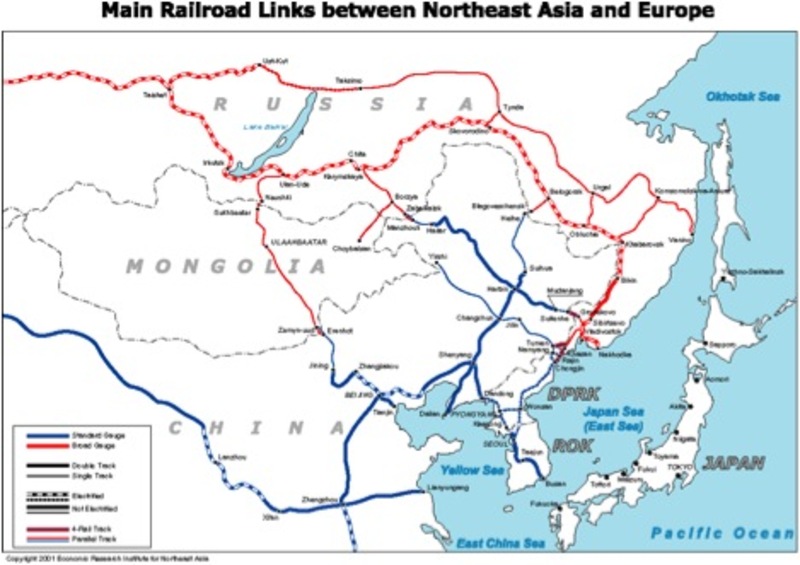

The Mongolian republic’s foundation myth, predating China’s Republican revolution, dates back to the eviction of a detested Manchu viceroy in 1911 and China’s political and ethnic domination of the parts of Mongolia it did retain – now the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region – is an affront and warning to Mongolian nationalists. Standing up to Chinese economic penetration is, therefore, good politics and may prove to be smart geopolitics. Economics, however, is another matter. Instead of simply linking Tavan Tolgoi to the Chinese railway system, Mongolia is trying to cobble together a coalition of Chinese, Russian, South Korean and Japanese concerns that will develop part of the mine jointly with Mongolia and, most importantly, build an integrated transport network 5,000 kilometers from Tavan Tolgoi to the Russian export facility at the port of Vanino.

|

Railroad map (2010) |

The objective of the Russian route is for Tavan Tolgoi coke to find a home in Japanese and South Korean steel mills, and to get to those mills through Russia (which has no coke import needs of its own) without being captive to the necessity of moving the product overseas through the shortest and most economical route-through Chinese railroads and ports. Total projected cost: US$5.2 billion. Additional transport cost per ton: perhaps $100. To bootstrap this diversification, the Mongolian government already requires that Chalco resell 30% of its current Tavan Tolgoi purchases to three Japanese and South Korean trading companies. Reportedly, this portion is delivered to Chinese ports for export. Somebody is enjoying a windfall, as Mongolian coking coal is apparently selling for a third of the price of the Australian product currently fueling Japanese and South Korean steel mills. Tavan Tolgoi itself is divided into east and west zones, East Tsankhi and West Tsankhi, each with its own challenges. West Tsankhi is the joint development mega project based on foreign operators investing in and operating the mine and paying royalties to the mine owner, state-run Erdennes Tavan Tolgoi. This is the piece wrapped up in the multi-national/railroad to Russia consortium idea. The Mongolian government announced a jumbled up award to an unwieldy collection of companies but has been unable to work out the deal it is trying to impose – which probably requires a hefty up-front payment that somehow has to be divvied up between the disparate partners, each of whom has different roles, profit expectations, and willingness and capacity to pay. East Tsankhi is the part of the mine that is already selling its output to China under the ownership and operation of state-owned Erdennes Tavan Tolgoi. Per government plan, Erdennes TT will go public in a multi-billion dollar global IPO that will sell a 30% share to fund the further development and exploitation of East Tsankhi by some combination of foreign and domestic construction, equipment, and service vendors.

Mongolia originally had ambitious plans to list the IPO on three stock exchanges simultaneously: Ulan Bator, Hong Kong, and London. The overseas exchanges are panting for the offering, which is expected to raise $3 billion. Underwriters are all clamoring for the business, leading to a fistfight between pinstriped antagonists in an Ulan Bator watering hole in 2010 and the generous decision of the Mongolian government to expand the number of underwriters to six in 2012. However, the IPO has been delayed several times, and the Hong Kong component has been dropped. The most recent prediction for the share sale is now mid-2013. Obstacles include uncertainty involving the award of West Tsankhi and the royalty revenue Erdennes TT would enjoy as a result.

A further complicating factor was a highly publicized exercise in resource nationalism: the sweeping decision to allocate 10% of the total stock of Erdennes TT to every one of Mongolia’s citizens and another 10% to Mongolian corporate entities. The government has also decided to give Mongolian citizens the opportunity to sell their Erdennes TT shares to the state for 1 million tugrik (approximately US $3000).2 The stock grant significantly complicated the business plans of Erdenes TT with respect to the IPO. The chief executive officer of Erdennes TT, B Enebish, explained the current state of play to the UB Post before he left his post in October 2012:

[T]he company that is going public should have a clear investors’ structure. But this is not the case for us. The Government made a decision to let the Mongolian public own 20% of TT. This means that the ownership of stocks are blurry because we do not know who will decide to keep or trade their stocks, or whether the Government will offer stocks to other companies or will they keep stocks themselves. We planned to resolve this in 2011 but the problem is still persisting even now. Two years ago, a resolution was passed from the State Great Khural on trading 30% of the company’s stake on stock exchanges. But another resolution [was] passed in January 2012 decreasing this percentage to 20%. On foreign exchanges, more specifically the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE), when a mining company is aiming to release on many different stock listings, it is required that at least 20% of the company’s stock is out. It means that we must determine exactly how many of our Mongolian citizens will return TT stocks for cash and make sure the stocks traded are more than 20% before proceeding to release TT stocks on foreign exchanges. 3

Enebish declared that Erdennes TT could boost its value in the interim by plowing more investment into production in East Tsankhi, thereby begging the question of where the money would come from – since it wouldn’t be coming from the IPO. The answer, at least in the near term, was China:

Since the IPO release has been postponed we see a definite need to find funding from a different source. We are discussing this with a number of investors, seeking to solve it through the sale of coal, presale of coal, and various loans.

Chalco, the same company that was subjected to the grand khural’s rebuke over its attempted purchase of South Gobi (which it subsequently abandoned), made a pre-payment of (depending who is talking, either $250 or $350 million dollars) to state-run Erdennes Tavan Tolgoi for coking coal. At the price Chalco is paying- less than US$70/ton, a far cry from the $200+/ton for Australian coking coal – that is over three years’ worth of exports. 4 However, it transpired that this cash transfusion was of virtually no help to Erdenes TT in funding its current operations, let alone financing its expansion. Erdennes TT is obligated to help fund Mongolia’s Human Development Fund. The Human Development Fund is funded by revenues from resource exploitation along the lines of the Alaska Permanent Fund and the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund. In other words, it is a non-renewable resource fund, albeit with Mongolian characteristics – i.e. it has become something of a piggy bank for politicians to curry favor with the electorate while slighting the restructuring of the economy against the day, admittedly far in the future, when all the ores are gone. In 2011, the payout from the fund accounted for 40% of the government’s budget, raising the specter of “Dutch disease” inflation the fund is specifically designed to avoid.

The 2012 payout was funded primarily by the Oyu Tolgai copper mine and the Chalco payment to Erdennes TT. 5 The Chalco payment to Erdennes TT amounted to about half of the value of the $500 to $600 million social welfare payout (in cash and services) that Mongolian politicians have promised to make from the nation’s Human Development Fund to Mongolia’s 3.1 million citizens in the runup to the June 2012 parliamentary election. In effect, then, Chalco got a bargain on coking coal while effectively bankrolling the Mongolian election-year giveaway meant to demonstrate the benefits of resource nationalism. 6 After the June 2012 parliamentary election the coalition led by the victorious Democratic Party apparently decided to push resource nationalism and determine what limits if any there were to the eagerness of foreign financiers, the tolerance of foreign mine operators, and the patience of the Chinese.

Unable to tap the bonanza of the longed-for Erdenes IPO, the government instead opted to issue $1.5 billion in government bonds. The issue—equivalent to 17% of Mongolia’s current GDP—was quickly oversubscribed by a factor of ten, which perhaps provides a misleading idea of the international appetite for Mongolian risk and respect for the wisdom of Mongolian fiscal management, especially since the government apparently had no concrete plans for how to use the funds and pay back the principal and interest.

Writing on his blog, The Mongolist, on January 16, Brian White observed:

The government has been criticized by the opposition Mongolian People’s Party (MPP) for not having a clear plan on how to spend the funds now that the government has received them. Prime Minister Altankhuyag has responded on behalf of his government that there is a plan in the works and a “Policy Council,” which he will chair, has been formed to ensure proper use of the funds. To me this is a far more frightening bit of news than the market scare brought on by MPRP. In the highly partisan and depressingly opaque environment of the Mongolian parliament, the current government has introduced USD 1.5 billion of revenue without a binding and clear statutory authority for how it should be spent. The government of Mongolia seems to have a tremendous amount of faith in the political system’s ability to produce a good outcome here. Moreover, the list of proposed projects for the revenue, which includes development of an industrial complex in Sainshand, expansion of the railroad, development of Tavan Tolgoi, and a potential subway system in Ulaanbaatar among other things, is shockingly broad when viewed in the context of reality. Just take the fact that Oyu Tolgoi (a single project) has required about USD 6 billion in financing thus far and it still has not begun full commercial production, and it is hard to imagine USD 1.5 billion going very far on the government’s wish list.

http://www.themongolist.com/blog/government/44-the-name-is-bond-chinggis-bond.html

In addition to funding some immediate investment needs, the Democratic Party coalition apparently hopes that it can gain leverage with investors by demonstrating it has the option of funding its resource development through the issuance of debt without giving away equity.

Case unproven, it seems, by the $1.5 billion issue. Foreign bond buyers were probably willing to take a flutter on a small issue of an exotic bond whose failure could not sink a diversified portfolio, a minor risk justified by the attractive theoretical fundamentals of Mongolia, namely its low baseline GDP and the potential for enormous growth of its resource sector.

However, an economic pundit ran the numbers in the UB Post (and also looked at the possibility that the government might turn to another $3.5 billion bond issue, in part to help pay for the first $1.5 billion) and drew the conclusion that Mongolia’s total foreign indebtedness had already reached worrisome levels:

As for Mongolia, the ratio of the total amount of our debt (USD 10.9 billion) to the GNI (USD 14.1 billion as the sum of GDP USD 8.5billion +USD 277 million transferred from abroad + USD 5.3 billion FDI) is 77 percent. And, the ratio of the total amount of debt to our export income, which was USD 3.8 billion, is 300 percent. When compared to average developing country, it is three times higher than the GNI and four times higher than the export income, which shows that the external debt of Mongolia is completely enormous.

http://ubpost.mongolnews.mn/?p=1600

Can the government keep its fiscal and business house in order—and continue to attract foreign investment and grow the economy at the 17.5% rate that caused all the excitement in the first place? In the new year, signals have been decidedly mixed, for reasons that are not entirely related to the weakening of Chinese demand.

On January 9, 2013, Erdenes TT management gave the Mongolian government the bad but not unexpected news that it was facing a shortfall of $200 million thanks to the election-year giveaway:

Earlier, “Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi” JSC has been financed first with 350 million USD in the form of advanced payment under the agreement established with Aluminum Corporation of China Limited (CHALCO), later received additional 131 million USD from GOLOMT Bank (Mongolia) and another 100 million USD from Development Bank (Mongolia), comprising a total of 581 million USD investments to date…only 270 million USD were utilized for Company’s activity from the total of 581 million USD invested, whereas the rest of 311 million USD was distributed to civilians accounting into Human Development Fund.

As to how the requested $200 million bailout will be used, management had this to say:

If to receive the 200 million USD investments, the activity will be normalized and citizens are able to receive their dividends from 1,072 shares distributed by the Government of Mongolia.

http://www.infomongolia.com/ct/ci/5469

To rephrase this rather fractured passage, some of the funds will be used to pay dividends to those Mongolian citizens who decided to hold onto their ETT shares (1072 per person) instead of selling them to the state.

Dividends have become an important issue because the new government repudiated the previous regime’s promise to buy back the 1072-share Erdenes distribution, making the payment of dividends something of a political imperative.

The government placed the blame for the financial shortfall squarely on the contract price negotiated by Erdenes TT (whose previous chief, B. Enebish had been forced to retire “for personal reasons” in October 2012 while being criticized by sources inside the government for “overspending” and “slowing the project down”) and the previous government with Chalco.

According to a deal that the former Government signed with CHALCO, Erdenes TT LLC sells high quality coking coal for 70 US dollar per ton to China. But the deal causes loss to the company.

And the inevitable corollary:

Therefore Erdenes TT LLC is trying to re-negotiate with China over the deal.

http://www.business-mongolia.com/mongolia/2013/01/10/erdenes-tt-llc-needs-additional-investment/

Whether or not Erdenes is actually selling coking coal to Chalco below its marginal cost (it recently claimed it was losing $8/ton) is an interesting question that is difficult to answer. All that can be said with confidence is that the government wants more money from the Chalco deal.

Presumably, Chalco, in light of the fact that it 1) prepaid for the coke which is as yet largely undelivered and 2) is aware that virtually all of the prepayment was transferred out to the Human Welfare Fund, is perhaps not eager to agree to pay more for the coking coal it hoped to get.

Bloomberg’s headline on January 17, 2012 revealed:

Mongolia’s Erdenes TT Halts Coal Exports to Biggest Buyer China

Erdenes TT’s new chief explained:

Exports to customers including Aluminum Corp. of China Ltd. stopped on Jan. 11 as Erdenes TT couldn’t pay Altangovi, said Yaichil Batsuuri, who has led the company since October. Altangovi provides warehousing services at the border with China, the biggest buyer of Mongolia’s steelmaking coal.

However, even in the same article, Batsuuri makes it clear that the real reason for the stoppage is not the relatively miniscule debt to Altangovi:

The halt comes as Erdenes TT seeks a government loan for as much as $500 million to repay debts and fund infrastructure construction, Batsuuri said last week. The mining company wants to raise prices and cut shipments, changing the terms of the $250 million contract it signed in July 2011 to supply companies including Chalco. . .

“The government made a resolution to make a new agreement with Chalco,” Batsuuri said…

In another phone interview with Bloomberg, Batsuuri took a further step toward burning his bridges to the Chinese by publicly revealing the price Erdenes TT was getting for delivering coke to the Chinese border–$53/ton—thereby earning a rebuke from Chalco, which would like to keep its cost figures under wraps in order to protect its resale margin (Erdenes TT’s previous statements had valued the deal at a considerably higher $70/ton).

The key question is whether the renegotiation represents a desperately-needed reordering of Erdenes TT’s finances and operations in order to get the China export business on a solid business footing—something that foreign investors might greet with a considerable degree of enthusiasm—or reflects a resource-nationalism strategy that is pummeling the Chinese for now, but might be turned against other foreign partners in the future.

Here is a relevant data point: The Mongolian parliament finally approved the construction of the railway from Tavan Tolgoi to China, the key infrastructure project that would allow Erdenes to stop the endless and costly caravan of 40-ton trucks heading to the Chinese border, unloading, and deadheading back to the mine.

The catch, as Charles Hetzler reported for AP:

Citing national security, the government ordered the rails be laid 1,520 millimeters apart, Mongolia’s standard gauge inherited from the Soviets. The width ensures that the rails cannot connect to China’s, which are 85 millimeters (about 3 1/2 inches) closer together. So at the border, either the train undercarriages will need to be changed or the coal transferred to trucks, adding costs in delivering the fuel to Mongolia’s biggest customer.

When it comes to China, Mongolia will only go so far and no further.

“This is a political decision,” shrugs Battsengel Gotov, the tall, boyish-looking chief executive of Mongolian Mining Corporation, which is building the railway from its prized coal mine…

http://www.northjersey.com/news/Mongolia_finds_China_can_be_too_close_for_comfort.html?page=all

Another data point is the furor over the new Mongolian resource law.

At the same time that the Mongolian government is, for lack of a more polite term, sticking it to the Chinese, it chose to alarm foreign investors with a proposed bill that would allow the Mongolian government to take free stakes in a number of “strategic” mineral projects.

Bloomberg reported on the clamor this proposed ox-goring raised among Mongolia’s resource development partners:

The legislation, which will give the state the right to a free stake in many mineral projects, will take the country away from the free-market principles practiced there since the early 1990s, Mongolia’s largest business group [the Business Council of Mongolia] said in a four-page letter sent to President Tsakhia Elbegdorj’s office on Jan. 7.

In addition to the general chilling affect that the law would have on investment in the mining sector, the business council raised the specter of Tavan Tolgoi:

“The draft minerals law will hurt all investment in mining in Mongolia, local as well as foreign,” Jim Dwyer, the executive director of the business group, said in an e-mail. “This would include the government’s huge Tavan Tolgoi coal project and Mongolia’s largest publicly-owned mine, Energy Resources.”

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-08/mongolia-group-says-draft-law-hurts-foreign-investment.html

However, it looks like the Tavan Tolgoi card, with its Chinese export focus, its muddled West Tsankhi consortium negotiations, and its faltering Erdenes TT IPO, is becoming increasingly tattered and devalued, at least in the eyes of the Mongolian government.

If Tavan Tolgoi becomes a dilapidated monument to the government’s resource-nationalist dreams, expect to hear more about another mine—Ovoot.

Ovoot reportedly contains coking coal reserves of a magnitude similar to Tavan Tolgoi. Its primary attraction, at least to the Mongolian government, is that it is situated in northern Mongolia, near the existing east-west rail line, and therefore can be integrated into the rail network connecting to Russia for the relatively modest cost of $1 billion.

The mine’s foreign investor, Aspire, has a railway construction subsidiary purposed to build the line, and is minority-owned by Noble, the gigantic Asian commodity house, which owns the rights to construct a coal export terminal in eastern Russia.

On the occasion of Noble boosting its stake in Aspire to 15%, Aspire told Bloomberg:

“Mongolian coking coal is largely being sold to Chinese steel producers,” Aspire said. “It is a key part of Mongolian development policy to establish access to seaborne markets for Mongolian coal, to provide pricing tension with Chinese customers and establish seaborne price benchmarks for Mongolian coking coal.”

The current Mongolian government, without a doubt is advancing a strategy of resource nationalism—and retreating from a “Mongolia is open for business” open investment policy– to increase its leverage in negotiating the extraction of its mineral wealth with foreign investors.

By this strategy, the most logical buyer of Mongolian coal, China, will be squeezed by increasing the costs and decreasing the margins associated with its sources in southern Mongolia. The government will do its best to exploit the negatives it has imposed on the China business to encourage the development of the Russian rail link from Tavan Tolgoi and /or the Ovoot mine to promote the viability of an otherwise significantly more costly route to market through Russia.

If all goes as planned, Mongolian coke will replace Australian coke in Japanese and South Korean, as well as Chinese, steel mills and Mongolia will leverage its expanded market access to capture a bigger share of the profits instead of giving them away to middlemen. Foreign investors, however, will not be unreservedly grateful to the Mongolian government for unleveling the playing field at China’s expense, for a variety of reasons that relate to the government’s attraction to overt resource-nationalist policies.

First, if foreign investment and resource companies acquiesce to the rough handling meted out to China, there is no guarantee that the same measures will not be applied to them in the future, either by this administration or the next victors at the Mongolian polls.

In this context, the proposed revision to the mining law—which gives the government the right to uncompensated shares in Mongolia’s biggest deposits—looks like a self-inflicted wound, administered, in the eyes of the foreign business community, by President Elbegdorj in order to endear himself to the electorate prior to the June 2013 presidential poll.

Second, the biggest operating and therefore investment payday is shoveling coal and copper into the maw of the Chinese industrial machine and/or using the Chinese railway system to transport coal to Chinese export ports for shipment to South Korea and Japan. Developers and investors will be less eager to pursue a Mongolian resource play that compromises the current bottom line and creates a down-the-road strategic risk by effectively subsidizing a less-competitive Russian export channel.

Third, governmental resource management has the potential to turn into a counter-productive carnival of politics, extravagance, and corruption, as the precedents of the Tavan Tolgoi welfare fund giveaway and the seemingly cavalier issuance of Chingghis bonds may appear to anxious investors.

On the one hand the Mongolian government is reducing the rate of return foreign investors can expect; at the same time it is increasing the uncertainty of those returns. From the point of view of Net Positive Value, the investor’s lodestar, the math is all heading in the wrong direction.

It remains to be seen if the promise of the Mongolian bonanza is rich enough to overcome these obstacles and attract the investment—and/or sell the debt– needed to develop the mines. The problems shadowing Mongolia’s coal export projects are a sign of the difficulties of reconciling the tension between globalization and resource nationalism, and a warning signal for Mongolia’s future.

Peter Lee writes on East and South Asian affairs and their intersection with US global policy. He is the moving force behind the Asian affairs website China Matters which provides continuing critical updates on China and Asia-Pacific policies. His work frequently appears at Asia Times. This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared at Asia Times.

Recommended citation: Peter Lee, “Mongolian coal’s long road to market: China, Russia and Mongolia,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 3, January 28, 2013.

Notes

1 Chalco Targeted as Mongolia Seeks to Limit State Deals, Bloomberg, May 17, 2012.

2 The 666,000 MNT will be distributed to elders and disabled civilians from next week, Info Mongolia, May 18, 2012.

3 Click here for the UB Post story.

4 Click here for a story by Info Mongolia.

5 Mongolia’s Quest to Balance Human Development in its Booming Mineral-Based Economy, Brookings, January, 2012.

6 Chinese, Mongolian companies sign $250m coal deal, China Daily, Jul 29, 2011.

Articles on related subjects

• Peter Lee, A New ARMZ Race: The Road to Russian Uranium Monopoly Leads Through Mongolia [here]

• Miles Pomper, Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, Stephanie Lieggi, and Lawrence Scheinman, Nuclear Power and Spent Fuel in East Asia: Balancing Energy, Politics and Nonproliferation [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Sino-Russian Alliance Comes of Age: Geopolitics and Energy Politics [here]

• Geoffrey Gunn, Southeast Asia’s Looming Nuclear Power Industry [here]

• MK Bhadrakumar, Russia, Iran and Eurasian Energy Politics [here]