More than two years after the triple disasters that included the meltdowns at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, between 160,000 and 300,000 Tohoku residents remain displaced, the power station teeters on the brink of further disaster, and large swathes of northern Japan are so irradiated they may be uninhabitable for generations to come.1 But today in Tokyo, it is as though March 11, 2011 never happened. The streets are packed with tourists and banners herald the city’s 2020 Olympic bid; the neon lights are back on and all memories of post-meltdown power savings seem long forgotten.

|

|

Given this mood of collective amnesia, the large poster on a wall near Shibuya Station comes as a surprise. It shows a little girl wearing a long red dress stenciled with the words “3.11 is not over” – nearby another poster depicts a Rising Sun flag seeping blood and the message “Japan kills Japanese.”

These posters – and dozens of others pasted around Tokyo – are the work of Japanese artist, 281_Anti Nuke. While the origins of his chosen name are murky, the way in which his subversively simple images force passersby to stop – and think – has led to comparisons with street artist, Banksy. But one major difference divides 281 from his British counterpart, whose works have been bought by Brad Pitt and Christina Aguilera: 281’s designs have incurred the wrath of Japan’s resurgent far-right who – goaded by the media – have branded him a dangerous criminal and urged the public to help put a stop to his activities.

This degree of controversy has forced 281 to wrap his true identity behind a veil of secrecy but after a convoluted series of negotiations, he finally agreed to meet for an interview in a Shibuya coffee shop. Throughout the talk, 281 wore a cotton face mask and dark glasses – anywhere else in the world, this would have made him stand out like a sore thumb but here among the capital’s fashion-conscious hay fever sufferers, he blended right in.

“On March 11 2011, I was in Tokyo when the earthquake hit. I’d never experienced anything like that before. It felt like a bad dream,” 281 explained in a soft-spoken voice belying the fury of his designs.

Like the other 30 million residents of Tokyo, he survived the initial quake unharmed but the following weeks triggered a seismic shift in his political outlook. “Before March 2011, I’d never been involved in activism of any kind. I’d trusted the Japanese government. But then the cracks started appearing,” he said.

First there were the revelations that the government had concealed the meltdowns, followed by news that they had hidden information regarding the dispersal of radiation – data that could have protected fleeing residents from exposure – and the fact that they’d allowed large volumes of tainted water to flow into the sea. 281 came to the conclusion that there was very little natural about this disaster – it had occurred as a result of ties between the Japanese government and the nuclear power station’s operators, TEPCO – both of which were determined to keep the truth hidden from the public.

Almost as disconcerting as the stories coming out of the crippled plants were the reactions of his fellow Tokyoites. “Everyone was acting the same. They were eating and drinking and going out as if nothing had changed. I wanted to let these people know what was happening in Japan.”

Around this time, 281 noticed that a handful of Japanese artists were beginning to produce works dealing with the meltdowns. One of these was the group Chim ↑ Pom who added a panel depicting the Fukushima accident to Okamoto Taro’s anti-nuclear mural Myth of Tomorrow in Shibuya Station.2 Artists like them made 281 realize that art could be used to spread activism. Despite having no background in art, he decided that the best way to spread awareness was to take his message to the streets.

Three months after the meltdowns – his anger with the government and TEPCO having reached critical mass – 281 felt compelled to take action.

The first design he created was a three-eyed gas mask with two mouth pieces and the word “Pollution” written below it.

The image satirized the logo of TEPCO, which was as recognizable to most Japanese residents as the golden arches of McDonalds or the Nike swoosh. 281 printed the gas mask onto 20cm-sized stickers then stuck them around central Tokyo on abandoned buildings and construction site barricades. He avoided private property – but had few qualms targeting the city’s ubiquitous TEPCO meter boxes and electric transformer units. “Anything owned by TEPCO was fair game. I felt no sense of guilt doing that.”

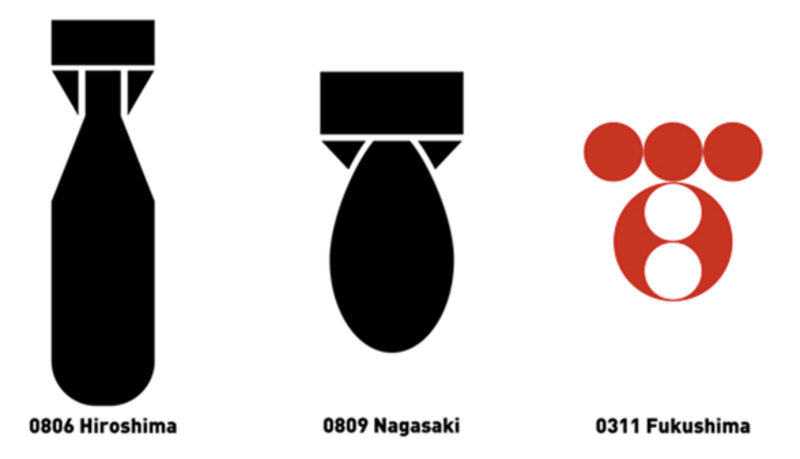

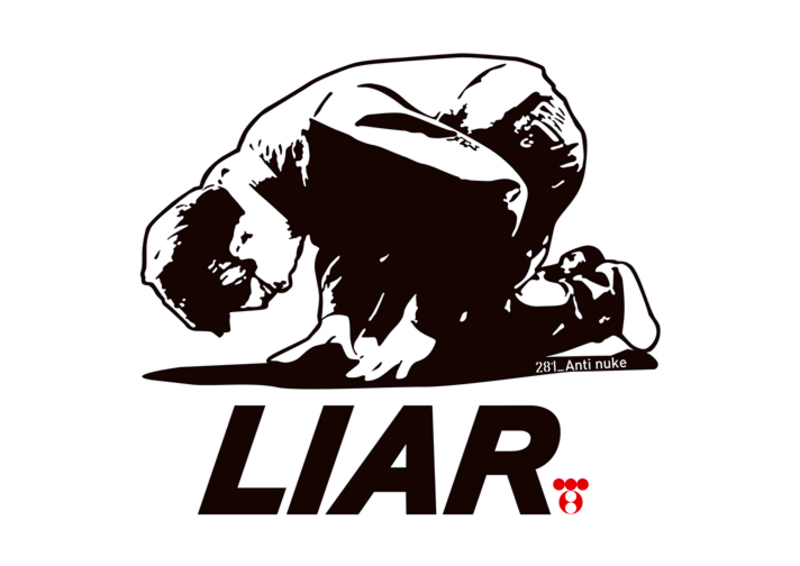

Over the following months, 281 put up hundreds more posters and stickers to remind the public what the Japanese government and TEPCO were conspiring to make people forget. One of them showed silhouettes of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs alongside the TEPCO logo. Another portrayed former TEPCO president Shimizu Masataka kneeling on the floor in his famous apology to evacuees in Fukushima in May 2011. 281’s message beneath the picture? Liar.

|

|

In contrast to the vitriol of these images, there is 281’s series of designs featuring a little girl wearing a poncho and rubber galoshes; below her feet are the words “I hate rain” punctuated with a triple-triangle radiation mark.

281 has created 200 different versions of this image. In some, her coat is made up of bright textiles, others use Hello Kitty wallpaper or a pattern of purple hydrangeas – the flower adopted by the nation’s post-3.11 anti-nuclear movement. 281 said he chose the different designs simply according to patterns that caught his eye and he wanted passers-by to find designs they liked, too.

The plan seemed to have worked.

Since 281 first designed the image in September 2011, it has been spotted the length and breadth of Japan – as well as in the U.S. and Europe. When he started to receive tweets to his account at @281_, he understood the reason for its viral spread. “The messages came from parents all over Japan. They told me they could see their own children in those prints.”

The same child in the “I hate rain” sticker features in other 281 designs. In one, she plays on a swing as radiation signs fall like snowflakes around her; in another, dressed in a swimsuit, she hugs an irradiated life-ring. Like all of 281’s work, the power of these designs lies in their simplicity. The radiation expelled by the twin meltdowns has tainted all aspects of children’s lives and cast doubts on the safety of everyday activities that used to be taken for granted.

The repeated image of the young girl raises the question of whether 281 has children of his own. Initially, he declined to answer but after some gentle persuasion, he conceded he was a father – but the girl was not based upon his own children. “Even before March 11, I’d had this image of a young child in my head.”

281’s comment touches on what makes cartoons as an art form so powerful. From simple smiley faces through Peanuts to modern manga, these images allow people to project onto them their own feelings. The more abstract the image, the easier this becomes. If 281 had chosen a real photograph for his “I hate rain” series, this would inevitably have created an empathy gap between ourselves and the viewer – but the generic nature of his image transforms the child from a girl into any girl.3

In order to spread his work, 281 has adopted a very democratic approach. The images are available for free to download from his website (listed at the end of this article). He has also harnessed the power of Japan’s convenience stores to spread his work – in the same way as you can order concert tickets, you can now walk up to a 7-11 printer, type in a code tweeted by 281 and print out an A3 poster of his designs for 100 yen. 281 said this system allowed both sides to remain anonymous – himself and people who want to print out (and presumably post) his designs.

The issue of anonymity is very important to 281. Notwithstanding the questionable legality of posting his designs on public property, the risks were elevated in December 2012 when the right-wing tabloid newspaper, Tokyo Sports, ran an article condemning his work.4

Sparking the outcry was one of 281’s posters depicting politician Abe Shinzo – then the leader of the opposition Liberal Democrat Party but today the nation’s Prime Minister – with a radiation-emblazoned bandana over his face and the message, “Don’t Trust”. The image was found by Tokyo Sports during national election season and it accused 281 of initiating a smear campaign. (They needn’t have feared, Abe went on to win by one of the biggest landslides in Japanese history.)

The story set the internet ablaze. On bulletin boards, Japan’s rightists – the so-called net uyoku5 – demanded 281’s immediate arrest for interfering with the election. Such commentators seemed oblivious to 281’s previous designs, which had been equally critical of Abe’s rivals.

|

|

One of his most scathing posters, for example, depicted Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko and Katsumata Tsunehisa, another former president of TEPCO, locking tongues in a deep French kiss. Beneath it was the slogan, “Kizuna” (bonds) – a word used by the Japanese government to promote a sense of national solidarity following the 3.11 earthquake.

In addition to online comments accusing 281 of interfering with the election, others claimed to reveal his true identity as a Korean artist living in Japan (he isn’t). Historically, Japan’s right has been quick to create scapegoats of resident Koreans – including the massacre of thousands of resident Koreans following the 1923 Tokyo earthquake. Recently such antagonisms have resurfaced due to maritime disputes between Seoul and Tokyo over control of Dokdo-Takeshima Islands. Right-wing protesters have taken to picketing Tokyo’s Korea Town in Shin Okubo and there was a large contingent of rightists present at January’s Okinawan rally in Hibiya to accuse island leaders of being stooges for both Korea and China.6

In response to the (mistaken) outing of 281 as a Korean, some of the commentators urged the killing of all Koreans residing in Japan. In spite of the violence spouted by some of the online commentators, 281 was keen to downplay the problem.

“Even if people hated the Abe poster, at least it created public debate. It went beyond just being a poster and made people think about the issue of politicians’ roles in the nuclear disaster. Something good came out of it.”

Asked whether he worried about his personal safety, 281 gave a quiet laugh, “The only protection I took was to buy myself a pair of sunglasses. I could begin to understand why Spiderman feels the need to wear a mask.”

281 had meant the comment as a joke but there was more truth to the superhero comparison than this modest man would ever admit. Science fiction is full of stories where radiation transforms the destinies of normal men. Following the apocalyptic disaster at Fukushima, this mild-mannered father was forced to take the law into his own hands to protect the life of his child – and the lives of children all over the nation.

The analogy seemed justified by 281’s next comment. “The meltdowns showed us that the Japanese government might not help us in the future. We need to save ourselves. Even after I die, it’s important to look after the next generation – and the generation beyond that.”

This sense of mission motivated 281’s latest series of works which targets the three key problems he believes Japan currently faces: the ongoing nuclear crisis, the rise in militarization and the planned entry into the Trans-Pacific Partnership. One of his new designs depicts three images of PM Abe wrapped again in bandanas – the first has the same nuclear symbol that sparked last year’s online outrage, the others, military camouflage and the American flag.

Recent calls by the Japanese government to amend the constitution worries 281 – along with millions of other people – that this is a first step away from the nation’s peace constitution towards rebuilding the nation into a military force. Equally worrying are moves to join the TPP which, 281 fears, would put Japan at the mercy of large U.S.-based multi-nationals such as Monsanto – the world’s leading producer of genetically-modified seeds.

Inevitably, works such as these will plunge 281 into the limelight once more. Some of his designs will move from the street to an art-space in Tokyo for his first show in June and 281 has just been signed up by a London management company. British filmmaker, Adrian Storey, has also just completed a documentary about his work titled “281_Anti Nuke.”

“281 is asking questions that must be asked. He puts his liberty at danger to reach out to people and show that art can be used to question our beliefs about society,” Storey explained. “I decided to make the documentary about him because his work deserves to be seen by a much wider audience. This kind of direct artistic activism is so valuable for societies everywhere and I hope it empowers other artists.”

People have been quick to dub 281 Japan’s very own Banksy – but such comparisons do him a disservice. Banksy’s art takes a scattershot approach to condemning capitalism – a viewpoint best summed up by his quote, “We can’t do anything to change the world until capitalism crumbles. In the meantime we should all go shopping to console ourselves.” 281 does not have the luxury of voicing such droll sound-bites. For him, the enemies of Japan are not amorphous big businesses or “the system”. 281 knows his enemies – they are TEPCO and the politicians who put and keep them in power; they have names and they have faces and – he believes – they are endangering the children of his country for profit. 281 is Banksy with a mission – and he knows that time is running out.

“Japan is at a changing point in its history. I want this country to find a better path. If we don’t give up, then I’m confident we’ll succeed in changing it.”

Very special thanks to Erina Suto – without whom this article would have been impossible. A trailer for Adrian Storey’s documentary can be seen here. More of 281_Anti Nuke’s designs – plus details of his upcoming show – are here.

Jon Mitchell is a Welsh-born writer based in Japan and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. In November 2012, “Defoliated Island”, a TV documentary based upon his research into the U.S. military’s usage of Agent Orange on Okinawa was awarded a commendation for excellence by Japan’s National Association of Commercial Broadcasters. The English version can be watched here. This is an expanded version of an article that first appeared in The Japan Times on 28 May, 2013.

Recommended citation: Jon Mitchell, “281_Anti Nuke: The Japanese street artist taking on Tokyo, TEPCO and the nation’s right-wing extremists,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 11, Issue 24, No. 5, June 17, 2013.

Related articles

• Sawada Shoji, Scientists and Research on the Effects of Radiation Exposure: From Hiroshima to Fukushima

• David McNeill, Life and Death Choices: Radiation, children, and Japan’s future

• Kerstin Luckner and Alexandra Sakaki, Lessons from Fukushima: An Assessment of the Investigations of the Nuclear Disaster

• Richard J. Samuels, 3.11: Comparative and Historical Lessons

• elin o’Hara Slavick, After Hiroshima

• Sumi Hasegawa, Paul Jobin, An appeal for improving labour conditions of Fukushima Daiichi workers

• Asato IKEDA, Ikeda Manabu, the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and Disaster/Nuclear Art in Japan

• Anders Pape Møller and Timothy A. Mousseau, Uncomfortable Questions in the Wake of Nuclear Accidents at Fukushima and Chernobyl

• Iwata Wataru, Nadine Ribault and Thierry Ribault, Thyroid Cancer in Fukushima: Science Subverted in the Service of the State

• Gabrielle Hecht, Nuclear Janitors: Contract Workers at the Fukushima Reactors and Beyond

• Paul Jobin, Fukushima One Year On: Nuclear workers and citizens at risk

• David McNeill, Crippled Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant at One Year: Back in the Disaster Zone

• Cara O’Connell, Health and Safety Considerations: Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Workers at Risk of Heat-Related Illness

• Matthew Penney, Nuclear Workers and Fukushima Residents at Risk: Cancer Expert on the Fukushima Situation

Notes

1. For a compelling summary of Fukushima’s problems two years after the meltdowns, read “Fukushima residents still struggling 2 years after disaster,” The Lancet, Volume 381, Issue 9869, Pages 791 – 792, 9 March 2013. Available here. For the debate on raising the bar on habitable levels, see here. As of June 2013, TEPCO maintains that decommissioning the reactors at Fukushima Daiichi will take between 30 and 40 years. See here

2. See Linda Hoaglund’s article on Chim ↑ Pom.

3. For further reading on the power of comic books, see Scott McCloud, “Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art”, William Morrow Paperbacks, 1994.

4. See: 安倍氏を風刺する“いたずらポスター”増殖中 , Tokyo Sports, December 8, 2012. Available here.

5. For a wider exploration of the trend, see: Xenophobia finds fertile soil in web anonymity, The Japan Times, January 8, 2013. Available here

6. For the weekly demonstrations at Shin-Okubo, see here. For the anti-Okinawan demonstration, see here.