|

Daylight Books, 2013

128 pages

56 color photographs

Essay by James Elkins

I’m staring at a blank white screen that awaits my text, but to type feels like a violation. What can be added to the sheer luminous emptiness in light (in the impossible violence of light) of the cataclysm of Hiroshima 1945? By taking on the incomprehensible destruction wrought by the atomic bomb in her book After Hiroshima, artist elin o’Hara slavick faces a void of annihilation that transcends expression, and yet, with meticulous care and consciousness, she produces photographic exposures that illuminate the unspeakable. Through works of troubling beauty, slavick enacts a temporal rupture, unearthing a moment that has been relegated to the historical past by saying, with stark but quiet clarity, that Hiroshima 1945 is not over.

– Amy White

The photographic images of Hiroshima, Japan, in After Hiroshima are attempts to visually, poetically, and historically address the magnitude of what disappeared as a result of and what remains after the dropping of the A-bomb in 1945. They are images of loss and survival, fragments, architecture, surfaces and invisible things, like radiation. Exposure is at the core of the photographic project: exposure to radiation, to the sun, to light, to history, and exposures made from radiation, the sun, light and historical artifacts from the Peace Memorial Museum’s collection. After Hiroshima engages ethical seeing, visually registers warfare, and addresses the irreconcilable paradox of making visible the most barbaric as witness, artist, and viewer.

– elin o’Hara slavick

To mark the publication of elin o’Hara slavick’s book, After Hiroshima, Amy White, arts writer and friend of the artist, talks with slavick about the photographic works she produced during the three months slavick spent in Hiroshima in the summer of 2008.

This interview is dedicated to Kyoko Selden (1936 – 2013), translator of After Hiroshima. She did not live to see the book, but she made it possible.

AW: When you knew you were going to go to Hiroshima, were you already beginning to plan the work that you were going to be doing there?

eos: Well, David Richardson, my epidemiologist husband who was going to Hiroshima to study the A-bomb data, had given me the idea of placing exposed, radioactive, A-bombed objects on x-ray film. He said I should see if those objects still have enough radiation to expose x-ray film, to make an autoradiograph. It was such a brilliant idea.

AW: Was that the first idea?

eos: Yes, along with the rubbings, because I had this incredible student – Lindsey Britt – who I taught for a conceptual photo class in Italy. I had the students make negative-less photographs and she did these rubbings on vellum of the letterboxes on people’s front doors in Florence at night, and then she brought her rubbing into the dark room and contact printed it. And I said, “Oh my gosh – how did you do this negative-less? Did you take a picture with a flashlight on a letterbox at night?” That’s what it looked like.

AW: I’m trying to imagine the process. Someone does a rubbing, and you take that paper with those marks and you place it directly onto photographic paper and you expose it? So the rubbing serves as a negative?

|

|

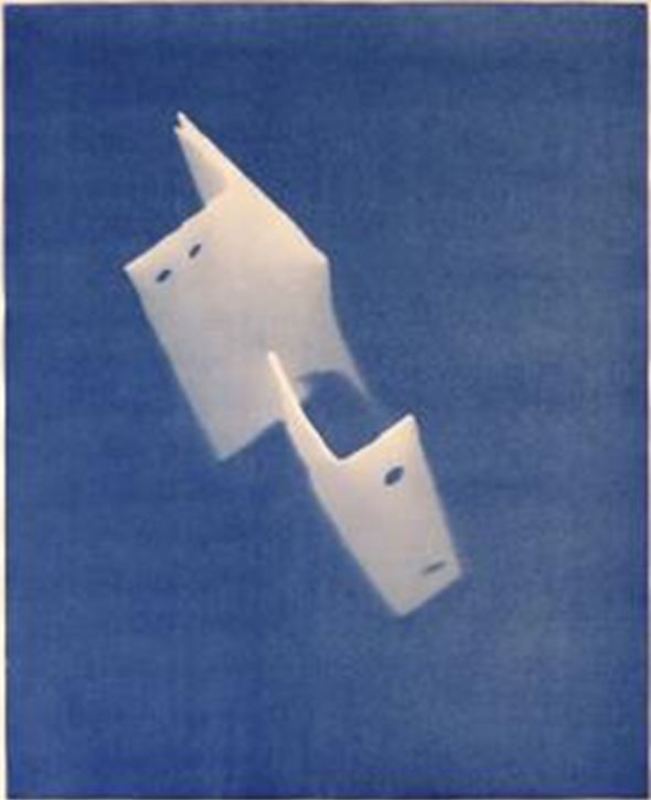

eos: Yes, the rubbing becomes the negative. The final result also looks somewhat like a negative, like an x-ray. It’s negative to positive and back again, which I love, because it’s all about exposing and tracing. I asked Lindsey if I could use her form, because other people have done rubbings – and probably other people have contact printed them in the dark room for all I know – but I’d never seen it. She said of course. So before I went to Hiroshima, I already knew I wanted to do the autoradiographs and rubbings of A-bombed surfaces. And then I got there and I re-read Carol Mavor’s essay in my book Bomb After Bomb, and I realized I had to do cyanotypes, especially re-reading her essay and going into the Peace Museum and watching the films.

AW: So the idea for doing cyanotypes came to you on site in Hiroshima?

eos: Yes. When you walk into the Peace Museum, you enter the lobby, and there’s this little film viewing room, and they show these two films all day long on the half hour. My first day there I watched those films and I just left the museum. I mean, I couldn’t even go in. It was terrible. I was just crying and crying. They’re amazing films. One is called Hiroshima and Nagasaki 1945, and the other is called A Mother’s Prayer, and they’re both amazing. And in those films – at least in one of them – there is footage that I’d never seen in the documentation – of grasses and plants, the shadows of them being left on walls – and the shadow of a ladder – after the bomb had been dropped. Some of them are white and some of them are black. And when I saw that and re-reading Carol’s essay, I knew I had to do cyanotypes.

AW: How were you able to achieve those exposures of radioactive materials like stump fragments from A-bombed trees?

eos: The x-rays?

AW: Yes.

eos: They are autoradiographs. An autoradiograph is an image produced by material that has been exposed to radiation, it is the registration of radiation onto radiation-sensitive film. Later I took the x-ray film and printed it on paper. I brought these heavy-duty, light-tight black plastic bags with me to Japan. I selected six fragments that could fit into the light-tight bags. The one autoradiograph (exposed x-ray film) that had the most visual registration (light specks, cracks and white markings) is of a fragment of an A-bombed tree stump. All of the others only registered little specks. The specks look like dust. There is something really important to me about there being actual physical contact. The same with the rubbings – like I’m rubbing the trauma, tracing and touching the trauma. So with the x-rays it’s actually the object that’s sitting on the x-ray film. Because people have suggested I could just do it digitally. You can plug these x-ray tablets into computers and you don’t even have the film – and you just have the image file. But it’s not the same.

AW: No, definitely. You lose that sense of contiguous, tactile, connectedness.

slavick handling a melted A-bombed bottle, 2008, photos by Madeleine Marie Slavick. |

eos: Yes. So I got the x-ray film, and in a very, very dark room I cut it up into smaller pieces and put the film into light-tight plastic bags. I was in the basement of the Peace Museum archive. There was this little room that they didn’t need to use for ten days. They let me use it to make the autoradiographs. I put the bags down flat on the table and placed the A-bombed tree bark onto the film and re-sealed the bags – I did six of them. My sister, Madeleine was there helping me. You have to wear gloves because a lot of the objects are fragile and crumbling. I left them in there for ten days. And then I returned and removed the objects and put all the x-rays in one big envelope and found this old man who ran a tiny photography shop to process it for me. When

I went to pick them up, there was this one, the one that’s in the book. It was the only one I printed. Because it had the most visual registration, the most evidence of radiation. And I have to say this – it was not really scientific. It could have been some of the oils from my fingers that made some of those marks. There could have been a light leak. It could be background radiation.

AW: But there’s such a burn to it.

eos: I know. [See Lingering Radiation, pictured at start of interview.]

AW: It somehow looks convincingly like radiation. It’s not a smudge of light. It’s more of a burn of light.

eos: I know. And there’s this crack of light, too.

AW: Yes. What do we do with that? We’re all excited from an aesthetic point of view, that we think the burn we see in the paper is so gorgeous and sparkly and looks like a super-nova or something – but the implications for the human beings who have to be around those objects…

eos: But then again [lifting a pen] you might put this on a sheet of x-ray film and it would register something. There is a

lot of background radiation. I did go to Japan with a Geiger counter. And for the first ten days I would carry it around.

AW: That’s so interesting, elin. I didn’t know that.

eos: And it would go off at times. It would probably go off here and many other places too. And finally I thought, I don’t want to walk around with this thing. It’s too weird. But, you know, there’s this really old cemetery up behind the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) where we lived, which was there before the bombing. The hill we lived on had been considered a safe zone. It was where a lot of people went after the bombing because it wasn’t on fire or destroyed – well, some of it was. It was even mentioned in John Hersey’s book, Hiroshima. He talks about people going to the temple at the base of the hill where I lived, that I by walked everyday, that survived. That was the line. After that, you were considered safe – or at least safer. But that cemetery up there would set the Geiger counter off like crazy.

AW: What you’re describing is very helpful. I’m trying to gauge your process, which I consider to be performative, or at least which can be construed as being performative. So your walking around with a Geiger counter in a cemetery is pretty rich, pretty intense. I see it that way anyway. I don’t think you designed it as a performance, per se, but it is performative. These gestures are really meaningful.

eos: I should show you this one picture. It’s from when I was doing the cyanotypes in the garden – there’s this little courtyard at the Peace Museum that’s only open to staff. They can eat their lunch out there. It’s called the Sunshine Garden.

|

|

AW: Sunshine Garden!

eos: It was right near the archive where I was working. So I’d come down the hall and I’d lay them out there and this wonderful woman from the museum, Mari, would help me and she took some pictures of me where I’m putting the objects down. And I’m in this green outfit, these crazy French pants with this Day-Glo green top and the cyanotypes were on the ground. and I’m like this: [demonstrates]. And I’m not posing.

AW: Of course not.

eos: I’m just moving something and it looks like such a dance piece. You know, you’re the first person to suggest performativity – I’ve never thought of it that way. But I felt like I was in a film so much of the time, like when I was in the basement at the Rest House (previously an office building for the city, the Fuel Hall) at Peace Museum Park. It was where a man went down to get paperwork when the bomb went off and he survived.

elin o’Hara slavick, Survival Basement Wall, 2008 |

AW: Is that where you saw the drips on the wall?

eos: Yes. He comes up. Everyone is dead. The city is on fire. He’s in living hell. And he survived and lived until his mid-80s. Mr. Nomura Eizo. And they left that basement as it was. And you have to get special permission to go down and you have to wear a hard hat. But no one is with you. So you’re by yourself and you go down the steps that he went down, holding the same banister, and you have this hard hat and there’s standing water and there’s cords hanging because they’ve got these industrial lights shining. And there are paper cranes and paper drawings covered in plastic that people leave as a memorial for him that are leaning against a wall.

AW: You had a cinematic feeling there.

eos: Not all the time, but yes. It’s a combination of things. Maybe a mix of performance and science. Exposing the autoradiographs. I felt like I was on stage when I was doing the rubbings because I was out in public.

AW: I’d like to know about the process of acquiring and handling the objects that you used for your cyanotypes – were they also from the Peace Museum?

eos: They’re all from the Peace Museum – except for the pieces of bark and leaves and flowers. They’d just fall off the tree and I’d pick them up and bring them home.

AW: But the bottles and comb and so forth –

eos: Those are all from the Peace Museum archive. The archive has over 90,000 artifacts. They bring them out in these plastic tubs. They’re all wrapped in white acid-free tissue, and sometimes they open one and, for example, with the pieces of rusted metal, there are bits all over the paper. They’re not going to last forever. They’re deteriorating. And you have to wear white gloves. Mari, who helped me, would handle the object, but I needed to put it down on the paper myself. Because I knew which way I wanted it. The first time I did a cyanotype, she handled the object and moved it a couple times while placing it down – but then she agreed that I had to do it. Because if you move it just after ten seconds there’s a trace –

|

|

AW: A blur –

eos: Yes. So she would let me put it down. And then I would expose it for ten minutes and pick the object up and give it back to her. And she would wrap it up. They have file cabinets full of images of each object in the archive. They do not have any ladders. That’s why I used an American ladder, because all of the Japanese ladders of the period disappeared. They were all made of wood in 1945 – so they were all incinerated. Or perhaps nobody gave one to the museum. Most of the objects in the Peace Museum were donated by families or survivors – or people who found them.

AW: So they were all contributed.

eos: Yes. So you go into these file cabinets – most of the objects are indexed as images, which are mounted on cardboard with all of the information about them, such as who donated the object, what it was, where it was found, and any other information they might have. And Mari would pick out the ones that I could work with – because I couldn’t have access to all of them.

|

|

AW: I think it’s important that we acknowledge Felix Gonzalez-Torres in this interview.

eos: If I had to choose one influential artist to name, it would be Felix Gonzalez-Torres, an artist who visually manifested loss, disease and death with post-minimal aesthetics and without a studio. For example, to speak of the perfect radical union of two lovers – Felix and his lover Ross (who was dying of AIDS) – Gonzalez-Torres hung two identical utilitarian clocks side by side and called it Untitled (Perfect Lovers). Aesthetics, politics and life are one. I think it’s interesting – the merging of domestic life and art – but I also felt deeply troubled in Hiroshima – by the fact that we were living in this dormitory building where doctors and scientists and military people had lived – just to study the victims – not to help them – but to study the victims of the A-bomb. It was built in 1947 by the U.S. Government.

AW: You were living and making your work in this space where American Military Medicine had studied – in a cold, detached way – the victims of the atom bomb?

eos: Yes.

AW: That’s significant.

eos: It’s where they lived. There was this huge industrial kitchen and a dining room, which was like living in The Shining hotel. Nobody was there. I mean the kitchen was dead. The dining room was empty. When our kids had friends over they’d bike around the dining room. I don’t know how many people once lived there, but it was weird. The research place was literally right down the driveway, a one-minute walk.

AW: You inhabited their domestic space – the domestic space of the American military/medical/industrial complex.

eos: I find it both symbolic and significant that I am an American making work about Hiroshima, in opposition to what the U.S. did (and continues to do with drone strikes, uranium tipped missiles, etc), and in the spirit of apology, international solidarity and historical understanding so that we do not repeat our mistakes. The Japanese people I have come to know through this project have all been incredibly grateful for my work, while simultaneously suffering through the representation of incalculable loss.

Amy White (@parallelarts) is a regular contributor to Indyweek, Art Papersand other publications. She has received numerous awards for her art criticism and has been shortlisted for the Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. She is also a practicing artist and lives and works in Carrboro, North Carolina.

Excerpts from After Hiroshima:

Tread Lightly, Please

Junichi Mizuno

This whole town by the river,

Where many new buildings now stand,

Was once, long ago,

One big graveyard.

Under this road,

Where many cars now pass,

Was once a little boy

Who crouched on the ground all day.

His heart broken, recalling his mother,

Who died, infested with maggots,

And burnt.

So I ask you,

Who now tread the streets of Hiroshima,

Please, tread lightly,

Walk with care, I beseech you.

For even now,

Many who were badly burnt

Still lie in the hospitals.

Even now, suddenly, somewhere,

A strange-looking person with crooked fingers,

Hiding an irregular twitch in the face

With dark black hair,

May be dying, right this minute.

So I ask you,

All who visit the city of Hiroshima,

When you walk the streets here,

Please tread lightly

Walk with care,

I beseech you, please…

Mizuno Jun’ichi is a Kobe-born author and advocate of Pax Turistica (peace through tourism). The family moved to Hiroshima in the fall of 1944. He was fourteen when he was exposed to radiation and lost his parents and all three younger siblings to the bomb. After a long search he located his mother. She died on September 14, 1945. According to a prose poem he wrote, she died while he was away briefly. Upon his return to Hiroshima, a friend took him to the river bank. In a little hollow under a tin plate were bones. He picked a few and put them in a brown envelope, and his friend wrapped it in white cloth. “Do Walk Quietly” is the final poem in his Symphonic Poems: Hiroshima, a verbal symphony in four movements.

|

|

From James Elkins essay On an Image of a Bottle:

To my eye, what makes this image immediately arresting is that it is a dim, bluish remnant of one of the most intense fluxes of light that people have ever produced. These images are shadowy, but they recall brilliance.

My claim is that the images in this book are shadows of shadows of shadows of shadows.

Each shadow was produced by a different light.

The first shadows were cast by the objects preserved in the museum in Hiroshima when they were struck by the radiation of the atomic explosion. The light that cast those shadows included eight kinds of radiation:

(i) Infrared, microwave, and radio waves. They would have caused the heat that started to melt the bottle.

(ii) Visible-wavelength light. It would have been blinding.

(iii) Ultraviolet light. Like the first two, its intensity would also have been blinding.

(iv) Alpha rays. The water in this bottle—if it had water—would have stopped the α rays, casting a shadow.

(v) Beta rays. The β rays would also have been stopped by liquid in this bottle, casting a shadow.

(vi) Gamma rays, would have passed right through the bottle, casting no shadow.

(vii) X-rays. The higher energy x-rays would have passed through the bottle; the lower energy x-rays would have been partly absorbed, possibly casting a shadow like the one in the image.

(viii) Neutrons, produced by the fission of uranium and plutonium. They would have passed through the bottle without interacting with it.

But that is not elin’s subject. The object in this case is only glass.

I have already made several errors. I should not have said that the visible-wavelength light and ultraviolet light would have been blinding, because a person near that bottle would have been instantly incinerated. I should not have said that the α rays and β rays cast shadows, because they are not visible to the human eye, and because any eye in the area of the bottle would have been incinerated.

This bottle probably did not cast a “death shadow,” and if it did, there is no record of it. And at the time, there were no eyes to see the other kinds of shadows this bottle may have cast.

A second set of shadows was cast by the objects preserved in the museum in Hiroshima when elin put them out in the sun, on cyanotype paper. LoneBlueBottle is a shadow. The light that cast that shadow included the same eight kinds of radiation, but in very different intensities and proportions. The only radiation that was registered by the paper was:

(iii) Ultraviolet light, which reduced the Iron in the paper from ferric oxide to iron monoxide. The result, after intermediate steps, is known to painters as Prussian blue.

The light that cast this shadow was not itself visible; therefore there was no shadow at the time. Or to be precise: the shadow elin might have seen when she prepared the cyanotype was not the shadow that was recorded on the cyanotype.

The cyanotype documents a shadow that was never visible, and that shadow recalls a shadow that was never visible.

These shadows of shadows of shadows of shadows—these pictures, in this book—also cause shadows on your retinas as you turn the pages. Those faint, curved shadows are also not visible to you: as Descartes first pointed out, we do not see the shadows in our eyes. We aren’t aware of what they look like. We are only aware that they exist. I have seen shadows in a person’s eyes, looking through a slit-lamp microscope. It is an astonishing experience, but it has nothing to do with ordinary vision.

The shadows of shadows of shadows pass across your retinas invisibly.

Why are the images calm, nearly empty, lovely, and soft? I am concerned that the simplicity of the beauty of her images is in an unproductive contrast with the storm of affect and pain in the original Hiroshima images. In other words: what concerns me is this particular use of beauty to answer something that is not beautiful, this particular absence of explicit pain, this disparity between the formal interests of her images and the ravaging content of photographs and films made in the days following the disaster.

Here is how I think of it. Making images of ladders, bottles, combs, and leaves is a way of saying: I cannot represent what happened to people in Hiroshima, because I cannot re-present it as art. It’s not that the people who suffered could not, cannot, or should not, be represented: it is that they cannot be re-presented in a fine art context. All that is left for art is to look aside, at other things, at surrogates, at things so ordinary and empty that they evoke, unexpectedly but intensely, the world of pain. I am not sure if this is ethically sufficient, but I think in this case it feels ethically necessary.

James Elkins’s writing focuses on the history and theory of images in art, science, and nature. His books include: What Painting Is; On Pictures and the Words That Fail Them; The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing; Art Critiques: A Guide; and What Photography Is, written against Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. He is E.C. Chadbourne Chair in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Translator’s Note

Kyoko Selden

While attempting to translate elin o’Hara slavick’s beautiful essay as well as James Elkins’s “ridiculously brilliant” introduction, I was made to think of light, shadow, reflection, projection, form, memory, flash, exposure, radiation, and development. In elin’s writing, light and shadow seem to merge into an artistic sphere of forms emerging from light and shadow of

the past and of memories arrested in re-enacted photographic images. The intricate conceptual and linguistic play passing between light and shadow was challenging but not impossible

to render into Japanese. The Japanese word kage, to begin with, means light, shadow, or form, though it normally means “shadow” or “shade.” The word sometimes means “light” as in a compound word tsukigake, moonlight, and at other times “form” as in another expression hitokage, a human presence detected from some distance. The word kage, in other words, means that which projects, and that which is projected. More difficult to handle were photographic terms like exposure and development, which carry multiple meanings, and of course the

keyword photography, recording by light. The Japanese word for photography, shashin, simply means “copying the truth,” or faithful-to-life reproduction, which contains no reference to

light. I sensed verbal awareness of photography as connected to light and exposure everywhere in elin’s essay. It was a pleasurable learning experience to try to reflect as much of those things as possible in the translation. In doing so, I saw elin’s photography as the art of speaking through light and shadow about what humans can do to and for other humans and things.

Kyoko Selden was coeditor of More Stories by Japanese Women Writers: An Anthology that is the sequel to Japanese Women Writers: Twentieth Century Short Fiction. Her other translations include Kayano Shigeru’s Our Land Was a Forest; The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki; Honda Katsuichi’s Harukor: An Ainu Woman’s Tale; and Cho Kyo’s The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty. She taught Japanese language/literature at Cornell University until her retirement.

From elin o’Hara slavick’s essay After Hiroshima:

How can I, an American citizen born twenty years after the dropping of the atomic bombs Little Boy on Hiroshima and Fat Man on Nagasaki, attempt to make art in response to Hiroshima? Like many, I have struggled with Adorno’s claim that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”. Adorno continued to write after Auschwitz, inspiring many to fight, write, and make art against the barbarism of war. Working from within conflict to reveal it is what many artists do, exploring the clash between: representation and reality, genocide and humanity, beauty and the wreck of our world, form and content, visual pleasure and criticism, the “sailing vessel and the shipwreck.”

Exposures to Hiroshima include seeing the film Hiroshima mon amour in high school and reading John Berger’s essay “The Sixth of August 1945: Hiroshima” in college. Berger speaks of Hiroshima as a calculated tragedy:

The whole incredible problem begins with the need to reinsert those events of 6 August 1945 back into living consciousness…What happened on that day was, of course, neither the beginning nor the end of the act. It began months, years before, with the planning of the action, and the eventual final decision to drop two bombs on Japan. However much the world was shocked and surprised by the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, it has to be emphasized that it was not a miscalculation, an error, or the result (as can happen in war) of a situation deteriorating so rapidly that it gets out of hand. What happened was consciously and precisely planned…There was a preparation. And there was an aftermath.

Woman with burns through Kimono, 1945. |

|

Another clear memory of Hiroshima involved my mother, who as a high school German teacher, had gone to Japan to teach English to schoolchildren. She traveled to Hiroshima and visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum where she bought a copy of Tsuchida Hiromi’s Hiroshima Collection, an unforgettable book of black and white photographs of artifacts from the Museum’s archive. Each object – a tattered school uniform, a deformed canteen, melted spectacles, and a girl’s slip – is photographed in a field of white. The surfaces of the objects are like charred earth, topographies of destruction and loss. I asked my mother for that book and she gave it to me.

I did not know that I would end up in Hiroshima years later, in 2008, making images of the same objects from the Peace Museum’s archive. I placed these artifacts on cyanotype paper (paper treated with potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate) in bright sun and then rinsed them in the tub in the RERF apartment provided through my epidemiologist husband’s research on the studies of atomic bomb survivors. (RERF, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, originally the ABCC, Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, was built by the U.S. Government in 1946 to study – not treat – the victims and survivors, and became a joint operation with the Japanese in 1975.) I watched as white shadows of deformed bottles and leaves from A-bombed trees appeared in fields of indigo blue.

The history of the atomic age is intertwined with that of photography. Uranium’s radioactivity was discovered through a photograph. In 1896, physicist Henri Becquerel placed uranium on a photographic plate to expose it to the sun. Because it was a cloudy day, he put the experiment in a drawer. The next day he developed the plate. To his amazement he saw the outline of the uranium on the plate that had never been exposed to light. He correctly concluded that uranium was spontaneously emitting a new kind of penetrating radiation and published a paper, “On the invisible rays emitted by phosphorescent bodies.”

The process and problem of exposure is central to my project. Countless people were exposed to the radiation of the atomic bomb. I expose already exposed A-bombed objects on x-ray film, but it is the radiation within them that causes the exposure. The cyanotypes of A-bombed artifacts render the traumatic objects as white shadows, atomic traces. The photographic contact prints of rubbings resemble x-rays, luminous negatives.

As of 2007, there were over 250,000 hibakusha (“explosion-affected people,” A-bomb survivors) in Japan, 78,000 still living in Hiroshima. Hibakusha Okada Emiko gave her harrowing account of survival as an eight-year-old girl. She concluded, “There are now over 30,000 nuclear weapons in this world. Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not past events. They are about today’s situation.”

elin o’Hara slavick is a Professor of Visual Art, Theory, and Practice at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and her BA from Sarah Lawrence College. Slavick has exhibited her work internationally and is the author of Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography (Charta, 2007), with a foreword by Howard Zinn and essay by Carol Mavor and After Hiroshima (Daylight Books, 2013), with an essay by James Elkins. She is also a curator, critic, and activist.

Recommended citation: elin o’Hara slavick, “After Hiroshima,”The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 11, Issue 19 No. 3, May 13, 2013.

Articles on related subjects

• Asato Ikeda, Ikeda Manabu, the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, and Disaster/Nuclear Art in Japan

• On Uranium Art: Artist Ken + Julia Yonetani in Conversation with Asato Ikeda

• Mick Broderick and Robert Jacobs, Nuke York, New York: Nuclear Holocaust in the American Imagination from Hiroshima to 9/11

• John O’Brian, On ひろしま hiroshima: Photographer Ishiuchi Miyako and John O’Brian in Conversation

• Yuki Tanaka, Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro – Confronting Images of Atomic Bomb Survivors

• Kyoko Selden, Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Messages from Hibakusha: An Introduction

• Robert Jacobs, Whole Earth or No Earth: The Origin of the Whole Earth Icon in the Ashes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

• Richard Minear and Nakazawa Keiji, Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen

• elin o’Hara slavick, Hiroshima: A Visual Record

• Hayashi Kyoko, From Trinity to Trinity