This article examines the sinking of the Cheonan, a South Korean navy ship, on March 26 2010. Known as the Cheonan incident, it resulted in the deaths of 46 seamen and gave rise to subsequent political developments that provide a barometer of the current status and future prospects of Korea’s democracy and of North-South relations. From a military perspective, the incident involved a serious breach of national security for the ship sank near the northern maritime border with North Korea.

|

The Cheonan incident quickly emerged as an emotionally gripping issue as the sinking was followed by drawn-out rescue attempts, salvage operations and finally a forensic analysis. It gradually grew to become one of the most contentious political issues as the South Korean government’s handling betrayed curious inconsistencies leading the media and the public to raise questions. The simmering political tension boiled over after a government-appointed investigation team concluded that the sinking was due to a North Korean torpedo, leading to South Korean retaliatory measures including a call to halt all inter-Korean exchanges. The public quickly noted serious problems in the government’s report, and the government responded with legal and extra-legal measures to silence critical voices. What began as the sinking of a ship was thus transformed into a test of the health of Korean democracy.

We argue that the reactions by the government and civil society to the sinking of the Cheonan corvette revealed important aspects of Korea’s democracy. First of all, it became clear that the political progress of South Korea would have serious limits in the absence of a meaningful resolution of inter-Korean tensions. The incident showed that security threats —actual or otherwise— stemming from the existence of the North could convince South Koreans to compromise on, or even suspend some, democratic principles. Democratization in the South carries a seed of its own deformation in what Paik Nak-chung calls the “division system.”1 However healthy South Korea’s democracy becomes, the division system remains a genetic defect that can slow down democracy’s growth or deform its shape.

For example, although Korea has since 1987 made significant progress in procedural democracy, and electoral systems in particular, the incident showed that inter-Korean issues were still off limits to a public that had no independent access to information on them. The government remained the only source of legitimate information on which the media and public had to rely in order to grasp basic facts related to North Korea. Its power over knowledge was central to the “governmentality” that kept discourses on the North frozen in enmity and democratic procedures in the South suspended in an authoritarian mode. This could be clearly seen in the process by which the government’s torpedo explosion theory established itself as the official truth, contrary to all scientific evidence. In the process, the administration completely excluded the legislative branch from the investigation, and the National Assembly abdicated its responsibility to check and balance the administration by dissolving its Special Committee on the Cheonan without substantial activities. The judicial branch also failed to exercise its role as an independent body in the series of trials related to the incident. With the collapse of the system of checks and balances among different governmental bodies, the administration labeled as pro-North Korea those citizens who raised questions about its “truth” and restricted their freedom of expression. In short, the Cheonan incident showed that South Korea’s democracy could be short-circuited in the name of national security.

However, the Cheonan situation also revealed positive potentials for Korean democracy. Despite the above-mentioned challenges to democracy, civil society remained sufficiently resilient to weather the government’s exaggeration of the security threat from North Korea – the so-called “North wind” – as a means to shore up public support for the government and to weaken the opposition. After the sinking, the government took a series of measures to maximize the ”North wind”. For example, the official announcement that North Korea torpedoed the Cheonan corvette was made just two weeks prior to the 2010 provincial election, followed by the 5.24 measure that froze inter-Korean relations. The government’s maneuvers, however, proved ineffective. Voters did not respond to the “North wind” in the same way as before, but bestowed victory on the opposition party. Although conservative newspapers and many other media blatantly assailed North Korea for the incident, two thirds of the population did not believe the state’s torpedo explosion theory.2 Moreover, NGOs such as People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD) and Solidarity for Peace and Reunification of Korea (SPARK) issued influential independent reports that challenged the government’s claims. The PSPD even sent an open letter to the UN Security Council that cast doubts on the results of the government-led investigation.

This article analyzes the limits and potentials of Korea’s democracy revealed through the events surrounding the Cheonan incident. Its purpose is not to demonstrate contradictions in the report by the Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (hereafter JIG) or to investigate the cause of the sinking.3 It instead aims to assess the current status, both limits and strengths, of Korea’s democracy by reviewing political developments related to the incident. Finally, it concludes with some suggestions for rectifying the problems in the JIG’s investigation of the Cheonan incident so as to advance Korean democracy under the new government inaugurated in March 2013.

1. Democracy’s Failures in the Cheonan Investigation

On 31 March 2010, the Ministry of Defense initially formed a joint investigation group composed of 82 experts, and on 12 April it constituted a group of 73 investigators to investigate the cause of the Cheonan incident. The ministry-led investigation was justified on the ground that the incident occurred during the US-Korea joint military exercise, but from the beginning this imposed limitations on the investigation because the military itself was directly involved in the incident. Given the nature of the case, independent organizations, the judicial or legislative branches, or civilians should have led the investigation. The fact that the ministry took the lead limited its transparency and objectivity. The failure to ensure the independence of the investigation damaged its credibility from the start and reflected the reality that national security issues still remain beyond the reach of civilian supervision.

It was nevertheless a step forward that civilians were allowed to participate in the investigation. Given that initially only 6 out of 82 members of the investigation team were civilians, the increase to 27 through the reorganization of the team could have greatly contributed to promoting internal democracy. However, the independence of the ‘civilian experts’ was limited by their background – they were either from government research institutes such as the National Forensic Service or the National Oceanographic Research Institute, or from Samsung/Hyundai Heavy Industries, which, as the nation’s top military contractors, take orders from the military. There were a few experts from Chungnam National University and Ulsan University, who were recommended by either academia or the National Assembly, and they were relatively free from the influence of the military.4 However, they were obviously outnumbered by those who were subject to government influence. In addition, 24 foreign experts were military personnel or government officials under the guidance of their respective governments, and 82 out of 98 assistant agents were soldiers. In short, the JIG was dominated by experts under the influence of the government or the military, a structural limitation that conditioned the investigation and hindered its independence and integrity.

Several cases indicate flaws in the investigation. First, the data that each subordinate team of the JIG analyzed and reported contradicted the conclusion drawn by the JIG. For example, after the Evidence Collection Unit of the Scientific Investigation Team analyzed the evidence collected from the ocean floor and the hull of the corvette, it concluded that it “was not able to identify any pieces of composite metal, which are consistent with a torpedo sinking the Cheonan (JIG Report, 120).” It also reported that “there were no signs of burn, splinters or penetration from the survivors as well as the dead”, and “most of the corpses show (···) few external injuries but circumstantial evidence suggests that they died from drowning (132).” Furthermore, they acknowledged that a proximity explosion would have caused a number of hearing impaired patients, but there was no one with this problem. Neither heat-induced damage, created by a proximity explosion (77), nor broken holes with a floral pattern on the hull were found (84). In sum, the Scientific Investigation Team’s report indicated that they did not find any splinters, holes, traces of shock, and heat-induced damage – which a proximity explosion would surely produce. This clearly ruled out the possibility of a proximity explosion of a torpedo.

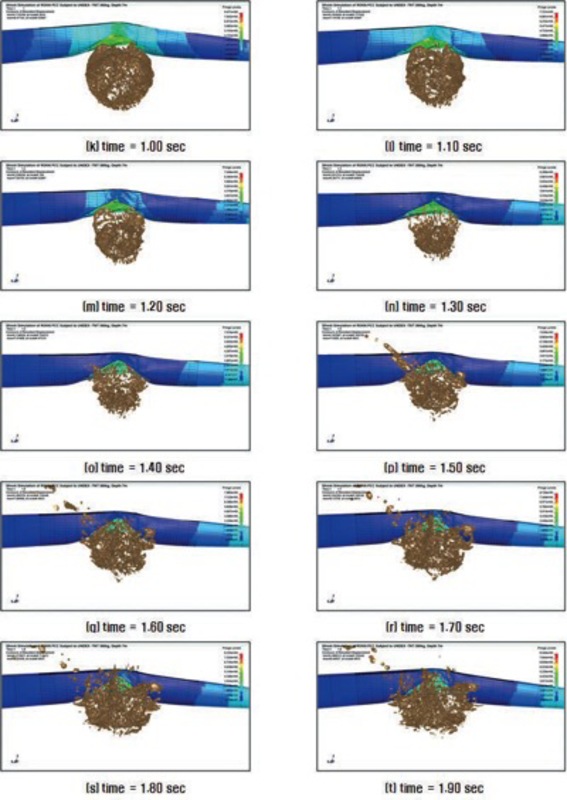

In addition, the analysis by the Hull Impact Analysis Unit of the Corvette Structure/Management Team contradicted the torpedo explosion theory. This team conducted an engineering simulation to demonstrate how the Cheonan would have been severed by the “bubble effect” generated by a torpedo, and reported its results from page 155 to 172 in the JIG Report. However, the team’s simulations showed that a torpedo explosion could make a hole in the middle of the ship but could not sever the Cheonan into two pieces. That is, the Hull Impact Analysis Unit proved through its own simulations that the Cheonan could not have been cut into two pieces by the bubble effect as the JIG concluded. The simulations showed that if there had been the bubble effect, the gas turbine room of the Cheonan would have been severed in the middle. But the salvaged ship revealed that the middle of the gas turbine room remained intact and only the front and rear parts were cut off. The only scientific inference that could be drawn from comparing the simulation results with the ship’s damage therefore would have been that no bubble effect had impacted the Cheonan.

Even though the data provided by different teams of the JIG strongly demonstrated no involvement of a proximity explosion such as a torpedo, the report concluded that a torpedo explosion destroyed the ship. Circumstantial evidence in the JIG report suggests that the undemocratic nature of the investigation team contributed to the contradictory nature of the report.

For example, the Scientific Investigation Team found high explosive chemicals such as HMX, RDX, and TNT on the Cheonan but did not reveal their origins. The report admitted that (we) “wanted to have the National Forensic Service conduct a chemical fingerprinting through an isotope analysis, comparing explosive chemicals from the US, France, Canada, Korea and the chemical residue from the corvette so that we can identify the origins of the chemicals. But, revealing their origins was prohibited (117).” The team did not provide further details – such as who, what, how, why – related to the ‘prohibition’, but it implied the existence of internal and external pressures imposed on their activities and reporting.

The existence of internal pressure can be inferred from other parts of the report. The JIG report includes six pictures (< 6-23> to < 6-28>), each of which shows only one side of the severed corvette, creating the illusion that the simulations resulted in the severance of the ship. To create the illusion, the simulation outcomes were cut into two pieces, and each piece was superimposed with the images of the respective part of the damaged ship. In other words, these pictures seem to have been doctored to fit the conclusion. They are significantly different from other pictures (< 6-14> to < 6-22>) that show no signs of manipulation and that rule out the bubble effect. The difference between these two groups of pictures suggests that there might have been two groups within the JIG – one experts’ group which carried out objective analysis and another which drew predetermined conclusions about the torpedo explosion – with the latter group dominating the JIG.

|

A simulation result, < 6-17> above shows that a bubble effect, even if one had hit the ship, would not have been able to sever it in the middle. |

This suspicion becomes stronger when it comes to the analysis of the so-called “adsorbed materials.” The JIG argued that the white powder lump found on the Cheonan’s hull and the propeller of the torpedo was “aluminum oxide and moisture” and presented the pictures (< 5-11> to < 5-12>) as evidence. However, while the data of the two materials were accurate, their interpretation was not. Professor Gi-young Jeong from Andong University, and Dr. Pan-seok Yang of the University of Manitoba in Canada examined the same ”adsorbed materials” and their additional experiments confirmed that the materials were a type of aluminum sulfate hydrate, a substance formed naturally at a low temperature. JIG experts were aware of the scientific conclusion,5 but someone in the JIG overruled the conclusion and added fabricated data from the test explosions in order to draw the conclusion that an explosion created those adsorbed materials. There was internal testimony that someone in the JIG played a leading role in forcing the interpretation that adsorbed materials resulted from the explosion.6

|

Figure 6-26 and Figure 6-23, however, created the illusion that the simulation showed: the severance of the ship in the middle. |

|

|

In conclusion, since the Ministry of Defense took the lead in investigating the case in which it was involved, the credibility of its findings was low from the start. In addition, according to the report and internal testimony, the JIG’s investigation was neither objectively nor fairly conducted due to the undemocratic character of the group. In essence, the process of the investigation on the Cheonan incident violated a core principle of democracy: civilian control of the military. It also violated the JIG’s organizational integrity as the independence and internal democracy of the JIG were not ensured.

2. Limits and Regress of Korea’s Democracy

While the Korean Constitution upholds the republican principle of the separation of powers and checks and balances among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the government, in reality so much power is concentrated in the hands of the president that there are few checks and balances from the legislative and judicial branches. Presidential authority is further enhanced by the president’s position as head of his political party. Given the hierarchical structure of political parties, the president’s position ensures that his policies will be supported by the party. If the party holds a majority of seats in the legislature, this all but guarantees that it serves as an instrument of the president’s policy implementation rather than a constitutional body that counterbalances the chief executive. The constitutional arrangement and party structure can combine to rear their anti-democratic face when the vibrancy of democracy recedes in society. And this was precisely the outcome during the Cheonan incident. When the incident took place, the president’s Grand National Party (GNP) had an overwhelming majority in the 18th National Assembly, and the parliament willingly abdicated its responsibility to keep the administration in check. Such willing acquiescence was a result of not only the political structures but also the characteristics of the issue—national security, as this section shows.

From the beginning of the incident, the National Assembly was entirely excluded from fact-finding efforts or formulating responses. As Chung-in Moon pointed out, “from the perspective of the trias politica principle, the announcement of the administration only covers half the truth.”7 Given that it was a crucial security issue and numerous suspicions arose surrounding the incident, the National Assembly should have taken responsibility to thoroughly investigate the incident, a responsibility that was all the more important because the incident involved the Ministry of National Defense, an executive body. Only an investigation by an independent body could ensure a degree of objectivity and neutrality, and it had to be the National Assembly. Its exclusion from the investigation process was a violation of the democratic and constitutional principle of the trias politica.

This is not to argue that the legislature did nothing. It did attempt to investigate, but its efforts were too feeble to produce any meaningful outcome. On 28 April 2010, the National Assembly passed a bill to form a Special Committee on the Sinking of the Cheonan, but that was its only tangible achievement. The committee failed to carry out any serious investigation – except for its reexamination of the so-called “adsorbed materials” – due to obfuscations by the GNP and the administration. Although the bill was passed on 28 April, the first meeting of the Committee was not held until 24 May because the GNP delayed submitting the list of members on the committee. Since the bill allowed operation of the committee only until 27 June, the GNP’s delay in effect left only a month. During that time, four official meetings were held, two of which were adjourned without any action because the GNP and the Ministry of Defense were absent on 26 and 28 May. As a result, the Committee composed of 20 lawmakers held only two meetings on May 24 and on June 11 before it was disbanded. Holding the two meetings was the only contribution that the National Assembly made to investigate the cause of the incident that involved the sinking of the corvette, the death of 46 soldiers, and the 5.24 measure that froze inter-Korean relations.8

It is not exceptional that the administration holds a dominant place in a security-related matter, but it is less common in other democratic countries that the legislature becomes so powerless. For instance, the bipartisan Church Committee formed by the US Senate investigated for two years in 1975 and 1976 intelligence gathering by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). While there have been many critics of the committee, it nonetheless released 14 reports and made recommendations to redress misconduct. Another case was that in 1989 when the Iowa turret explosion occurred, resulting in the death of 47 crewmen, the US Congress held hearings to inquire into the Navy’s investigation and had its General Accounting Office (GAO) review the results of the investigation into the explosions. In the wake of the September 11 attacks, the US created the bipartisan 9/11 Commission and for two years it investigated why the attacks could not be prevented. While these cases have received many criticisms, their activities bring into relief the paltry record of Korea’s National Assembly.

In contrast, there is no case in Korea in which any security issue, particularly an issue related to North Korea, has been investigated independently by the National Assembly. This can be explained by the structural problem of the government bodies and modern history. However, given that both factors can be attributed to the division between North and South within the Korean Peninsula, the issue of the division of the country is a structural constraint that severely restricts democracy.9

Under Korea’s presidential system, the President is entitled to submit a legislative bill, declare a national emergency, propose to amend the Constitution, hold a referendum, appoint the president and other judges of the Constitutional Court as well as the Chief Justice and Justices of the Supreme Court, and grant a general amnesty. That is, the President exercises “super-power”, which transcends that of the legislative and judicial branches.10 In addition, as a minister can hold a concurrent position as a lawmaker, the current structure does not ensure systematic and actual checks and balances between the executive and legislative branches. The outcome is also interlinked with the emergence of the Third Republic, the Yushin Constituton, and the Fifth Republic. However, the division of the country was a structural factor. That is, the gradual strengthening of the presidential system was justified on the ground that it was necessary for social stabilization and national security given confrontation between North and South Korea.

The independence of the legislature has been encroached upon since the Constitutional Assembly was formed in 1948. Although the Assembly enacted a Law for the Punishment of Anti-National Activities on 22 September 1948 to punish those who had collaborated with during Japanese colonial rule, it could not investigate, much less punish, such “anti-national activities”. The administration, within which former Japanese collaborators occupied many important posts, opposed the legislature’s initiative and interrupted the process; and outside the government some former collaborators threatened and assassinated members of the Special Investigation Committee for Anti-national Activities. The Committee was dealt a fatal blow by the “National Assembly Fraction Case,” and in effect stopped functioning. The case in which many lawmakers were charged with being agents of the Workers Party of South Korea resulted in the imprisonment of 13 lawmakers, even though there were neither witnesses nor objective evidence.11 The case left permanent trauma on lawmakers who challenged the administration. That is, it could be dangerous, even life-threatening, to be associated with a leftist organization. Later, the National Assembly attempted to investigate massacres of civilians committed by the military during the Korean War – again in vain.12

After those events took place, the National Assembly became weaker and less interested in checks and balances so that the executive as the president gained more power during the Yushin and the Fifth Republic. Because of history and structural weakness, the legislative body has developed a distaste to confront the executive on issues related to national security or North Korea. It may even have internalized self-censorship when it comes to these issues for fear of political liability or legal troubles. This may go a long way toward explaining why the National Assembly was so passive on the Cheonan incident, remaining dependent on the government.

More than a year after the Cheonan incident, the National Assembly became a scene of heated exchange during a confirmation hearing, a development that testified not only to the still explosive nature of the incident but also the decline of legislative independence. When a hearing was held on 28 June 2011 to confirm the appointment of Cho Yong-hwan as Constitutional Court justice, Cho, when asked about the incident, gave a politically correct answer: “It is highly possible that North Korea did it.” When Rep. Sun-yeong Park (Advancement Unification Party) further inquired, “You mean you are not sure that it was North Korea?” however, he crossed the red line. He answered “I accept the government’s explanation but since I did not witness it in person it is not appropriate to use the word ‘sure’.”13 Not only did that answer cost him his job, it also became the ground on which the National Assembly rejected a constitutional court judge appointment for the first time in its history. It was an unfortunate development for Korea’s democracy. Until the incident, the National Assembly had been slowly and carefully reclaiming its independence by taking measures to investigate past wrongs committed by the executive branch. For example, on 5.18, it held a hearing on the Gwang-ju Uprising that paved the road to the later imprisonment of former presidents Chun Doo-Hwan and Roh Tae-Woo, and created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that investigated civilian massacres and other wrong doings committed by the military and police during the Korean War. Now such progress seems in jeopardy or even in retreat as the National Assembly upheld the administration’s problematic claim as the absolute truth against which no shadow of doubt could be cast.

Such regression of democracy was also found in the relationship between the government and citizens. In the wake of the Cheonan incident, the government released contradictory information regarding the time, the location, and the cause of the sinking without reliable evidence or firm confirmation, and thus discredited itself. Hence it was natural that the press and citizens raised many questions about the incident and the government’s accounts. However, not only did the government refuse to provide reasonable responses and to communicate with critics, it also tried to use its authority to intimidate them into silence.14 In order to prevent any attempt to raise suspicions, the government used legal measures such as a libel suit in one case and utilized surveillance and pressure in another.15 As a result, “the government has failed in its central task to unite the nation”16 when such leadership was sorely needed. Instead it relied on repressive measures to restrict freedom of expression and conscience.

In May 2012 President Lee Myung-bak on radio referred to the citizens who raised suspicions about the Cheonan incident as “a pro-North Korean group inside the South who repeat the argument of (North Korea).” Such statements showed that the government lacked understanding of democratic principle or at least was willing to sacrifice it for political gain. However, it is also a legal reality that if people “literally repeated the argument” of North Korea, it would constitute a violation of the National Security Law, potentially resulting in a prison term. While some right-wing groups charged some of those who questioned the JIG for violating the law, however, the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office dismissed all those accusations in relation to the Cheonan incident. Yet the president as the head of the administration ignored the decision by the prosecutors and publicly accused those citizens of being ”pro-North Korea,” an act that bent the rule of law and compromised the principle of the presumption of innocence. Furthermore, under the circumstance in which the judicial branch did not render any verdict on charges based on the National Security Law (because no case was brought to the court), the president’s accusation of critiques as ‘pro-North Korea’ was a serious encroachment of the democratic principle of the separation of powers.

3. Civil Society Resilience and Democratic Space

As discussed above, the Cheonan incident shows the regression and limitations of Korean democracy, but also elements of progress. The government sought to heighten tensions between North and South Korea and to create a security political situation, but failed to gain the intended results. Civil society and some media raised suspicions and disputed the government’s explanation. Despite government efforts to repress such voices, a large number of citizens remained skeptical of the government’s argument. That is, the incident ironically had the effect of demonstrating the maturity of democracy in Korea.

On 20 May 2010, the JIG released a report accusing North Korea of sinking the Cheonan corvette. Four days later President Lee Myung-bak issued a statement that condemned North Korea’s military provocation. In addition, the government linked the issue directly to a security agenda by emphasizing the importance of the military in a series of fund-raising events for victims of the incident. Previously, such government efforts had led people to accept its argument as fact. Even when suspicions arose, there were few organizations that could dispute the government’s stance with substantive information. And, if so, they were incapable of communicating effectively with the public.

However, this time it was different. NGOs such as the PSPD raised crucial questions revealing weaknesses in the government’s argument. The PSPD, for the first time among NGOs, issued an official statement criticizing the Ministry of Defense for being too secretive about its investigation and continued to examine problems in the government’s response to the incident. They pointed out that the government was not even able to figure out the exact time of the sinking and also questioned claims of an underwater bubble-jet-explosion, whether North Korea had launched a torpedo attack, and the very existence of Yono class submarines in North Korea and their infiltration. They organized multiple debates to draw public attention. The organization submitted a request for disclosure of Cheonan-related information along with Lawyers for a Democratic Society, and when the request was denied, they filed administrative litigation to reverse the decision on behalf of 1160 citizens. Furthermore, when the international community solely relied on the Korean government’s announcements for its understanding of the incident, the PSPD sent a letter to members of the UN Security Council raising questions pertaining to the government-led investigation.17 For its part, the government was prudent in its approach toward the PSPD. Given the importance of the matter, the government chose not to be overtly repressive toward the organization. This absence of overt repression illustrates that a political space for NGOs has expanded in the past three decades.

The development of the political capacity of NGOs such as the PSPD is closely related to the freedom and influence of press. It is obvious that for NGOs to effectively deliver their messages to the public, a strong independent press is crucial. In addressing the Cheonan incident, the conservative press advanced the torpedo theory even before the government, but some others exercised a significant level of independence from government pressures. For example, an investigative TV show called “Investigation–60 Minutes” of the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) broadcast the findings of its own experiment and analysis that had failed to discover oxide, which is a natural byproduct of a torpedo explosion. Pressian, a respected online press, also played a significant role in raising questions about the government’s conclusion by introducing numerous in-depth analyses by civilian scientists. By presenting different views of scientists based on evidence, Pressian helped readers to learn about out the unscientific nature of the government’s argument. They provided clear and comprehensible explanations on such abstruse issues as adsorbed materials and the nature of a torpedo explosion so that the public could understand and even raise questions concerning the government’s stance. In addition, Hangyore 21, a weekly magazine, and “News Desk”, a major TV news show, of the Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) critically examined the government’s announcements and raised suspicions among the public. These efforts by the mass media were particularly valuable given the pressures from the government. In the case of “Investigation—60 Minutes,” pro-government high-ranking officials directly and indirectly intervened in the production of the program18 and at one point it was even unclear whether the completed program could be broadcast.19 Moreover, after the program was aired, the Broadcasting and Communications Commission issued a warning to the producer and staff about broadcasting “unconfirmed contents”.20

Another important element was the advance of citizen consciousness. Despite various government efforts, citizens were not swayed by the security political situation as much as the government wished. According to a poll on the credibility of the government’s announcement explaining the Cheonan incident in 2010 when the sinking took place, only 32.4% of respondents answered either “fully trust” or “somewhat trust”. On the other hand, 35.8% answered “do not trust at all” or “somewhat do not trust”. It is noteworthy that the trend remained the same in 2011 (33.6% vs. 35.1%).21 The 2011 poll was taken around the time of the Yonpyeong incident, when North Korean shelling of the island caused casualties. Therefore, a worried public was in a situation in which it could have been highly susceptible to the government’s argument that North Korea was to blame not only for the Yonpyeong incident but also for the Cheonan incident. However, citizens remained surprisingly suspicious of government explanations of the Cheonan incident.

Public doubt over the government’s explanation of the Cheonan incident surprisingly contributed to a crushing defeat of the majority party, the Grand National Party (GNP) in the provincial election in June 2010. The security politics based on fear of the North Korean threat not only failed to help the GNP to win the elections but adversely impacted the party.22 A majority of people (69.3%) believed that the government’s apparently clumsy explanations of the Cheonan incident was politically motivated. Almost half of the supportsof the majority party (41.2%) as well an overwhelming majority of supporters of the Democratic Party (90.3%) shared such a suspicion. Moreover, the public paid less attention to the incident than the government and the GNP might have hoped. Less than half the supporters of each party (40.1% and 48.2% respectively) report taking the incident into consideration when voting. In addition, 70% of voters did not change their support for a candidate due to the incident, and those who did change their support from the majority party to an opposition party (12.7%) were overwhelmingly more numerous than those who changed support from an opposition party to the majority party (2.4%). In other words, the Cheonan incident did not create the political diversion often called the “North Wind” in South Korea but resulted rather in a ‘reverse wind’, signaling that Korean democracy has greatly progressed.

4. Remaining issues and the prospects for Korean democracy

Nevertheless, the Cheonan incident reflects both the limitations and the potential of Korean democracy. On one hand, the government’s investigation was marred by its manipulation of power, revealing the shortcomings of Korean democracy. On the other hand, the government failed to control the public, testifying to the growth of civil society including independence in some sectors of the media. Should further political development in South Korea result in addressing the sources of doubt over the incident, it would mark a a major step for Korean democracy to expand into the security sector. It would also involve a step toward overcoming the legacies of hot and Cold War on the Korean Peninsula. But for the moment, the Cheonan incident helps identify the urgent task confronting the political leaders of South Korea: the easing of tensions between North and South Korea. Why? Here are three reasons.

First, the inter-Korean confrontation is the cause of tension in the regional politics of Northeast Asia, which, in turn, takes political space away from civil society and undermines democracy. For example, amid rising tensions in a series of crises such as the Cheonan incident and the Yeonpyeong Island incident, the US government dispatched the aircraft carrier George Washington off the Yellow Sea near Korea in late 2010. North Korea and China regarded this naval maneuver as a threat to their national security and raised their alert levels. Meanwhile, some Japanese citizens abandoned the campaign opposing the expansion of a US Marine base on Okinawa. At the same time, the return to power of the LDP under Abe Shinzo, has given impetus to the move to revise the Peace Constitution within Japanese politics. Such tensions in regional security impose structural pressures on South Korean democracy.

Second, inter-Korean tension has the effect of strengthening the rationale for the National Security Laws and providing a pretext for their implementation. As long as there is a law which punishes people’s fundamental freedom – freedom of thought and consciousness – as the security laws do, Korean democracy is not only incomplete but also carries the danger of regression in the event that security issues arise. For example, in January 2012, photographer Park Jung-geun was detained on charges of violating the security laws . The charges against Mr. Park were highly controversial. The government denounced him for retweeting the tweets ‘Uriminzokkiri,’ a twitter account run by the North Korean government even though he claimed that he retweeted them in order to mock the North Korean regime. It is impossible to expect a healthy democracy to flourish on a legal foundation where freedom of expression can be repressed simply because North Korea is involved as the security laws dictate

Third, inter-Korean tensions impede not only freedom of individuals but also debates and development of consciousness in society as a whole. It is easy to find cases in which inter-Korean tensions suppress freedom of social consciousness. In South Korea, people do not use the word tongmu, which means friends. Even though the word was once popularly used, since North Korean communists began to use it to address each other it became taboo in South Korea. People also demonstrate overly negative and emotional reactions to anyone or anything associated with communism or socialism. In fact, as we know, all capitalist societies have adopted and adapted such elements of socialist- or communist-inspired programs as social security and other welfare programs. South Korea is no exception. Yet, South Korean society’s allergic reactions have impeded systematic studies of theoretical and substantive contributions of such systems and prevented open debates. It is timely to consider the political outlook of South Korean politics following the inauguration of Park Geun-Hye as president in February, 2013. Ms. Park’s remarks thus far suggest that she may lack the needed understanding or the willingness to open a full and genuine investigation of the incident. Right after the incident she commented that there were many aspects of the episode that people could not understand and the government and military must leave no room for doubt.23 However, her flexibility quickly evaporated as the government issued its formal report on the incident in which it identified a North Korean torpedo attack as the cause of the sinking. She supported president Lee Myung-bak’s decision to terminate all exchanges with the North, including humanitarian aid although excluding those with the Kaesung Industrial Complex.24 Unlike President Lee, who extinguished all possibility of talks between North and South, President Park opened the possibility of conversations, but on one condition: an apology from North.25 Especially after the Yonpyeong incident, her approach toward the North hardened.

As Congressional elections and the Presidential election of 2012 approached, she began to put more weight on deterrence and retaliation than on conversation with North, even while recognizing the latter as a necessity.26 For example, she recognized the need of peace and stability in the Korean Peninsula and called for the establishment of a liaison office for inter-Korean cooperation, support for international investment in the North, and South Korean investment in special economic zones in Najin and Sunbong.27 However, her suggested policies for better ties with the North seem bound by a desire to appeal to her conservative supporters. Ms. Park, for example, strongly condemned the call for reinvestigation of the sink of the Cheonan, rejecting the critiques of the government. In the larger picture of inter-Korean relationships, she has refused to discuss with the North the Western sea border, the Northern Limit Line, even though disputes over the line have resulted in repeated clashes and occasional casualties on both sides. All in all, her potentially productive approach to the North seems limited by an inability to address the security issues without which any progress will be hard to gain or maintain. The lack of discussion of security issues has already heightened tension in the area. Without any security guarantees from the US and its allies in Northeast Asia, North Korea continues to develop nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles. This puts heavier pressure on Park not to yield to the North and strengthens the voice of conservatives in South Korea.

This article has examined the limitations and prospects of Korean democracy in light of the Cheonan incident. Democracy is not a purely domestic issue. Korean democracy is not complete and can be jeopardized by the lack of political stabilization and economic development in North Korea, by North Korean isolation in the international community, and by the failure to ease tensions in Northeast Asia. It is possible that a new socio-political paradigm will appears as a new president takes office. However, any social and political development will be incomplete and limited without easing tensions between North and South Korea.

* This is a translated and revised version of Sǒ Chaejǒng Nam T’aehyǒn, “Ch’ǒnanham sagǒni poyǒjun han’guk minjujuǔiǔi hyǒnjaewa mirae,” Ch’angjakkwa pip’yǒng No. 157 (Fall 2012). We gratefully acknowledge Narae Lee’s assistance in translation.

Recommended citation: Jae-Jung Suh & Taehyun Nam, “Rethinking the Prospects for Korean Democracy in Light of the Sinking of the Cheonan and North-South Conflict,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 11, Issue 10, No. 1, March 11, 2012.”

Jae-Jung Suh is Associate Professor at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. He is the author of Power, Interest and Identity in Military Alliances. He may be reached at [email protected].

Taehyun Nam is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Salisbury University in Salisbury, MD, USA. His research focuses on mobilization and domestic conflicts. With Robinson Leonard he is the author of Introduction to Politics. His email address is [email protected]

Notes

1 Paik, Nak-chung. 2011. The Division System in Crisis: Essays on Contemporary Korea. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

2 Kang Wǒnt’aek, “Ch’agidaesǒn’gwa taebukchǒngch’aek [Next Presidential Election and Policies toward the North],” 2011 T’ongilǔisikchosapalp’yo, Institute for Peace and Unification, Seoul National University, 2011, p. 104.

3 Seunghun Lee and J.J. Suh, “Rush to Judgment: Inconsistencies in South Korea’s Cheonan Report,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 28-1-10, July 12, 2010.

4 Ministry of National Defense. The Joint Investigation Report on the Attack against ROK Ship Cheonan. Seoul: Ministry of National Defense of the Republic of Korea, 2010, 38-42 [in Korean]. This is referred to as the JIG Report hereafter.

5 “Ǔimunǔi ch’ǒnanham, nonjaengǔn kkǔnnana? [Questionable Cheonan, is the debate over?],” Ch’ujǒk60pun [60 Minutes of Investigation], KBS, November 17, 2010.

6 Hwang Junho, “Sǒjaejǒng Isǔnghǒn, ‘Ch’ǒnanham habjodane chojak chudohan inmul itta’ [Suh, Jae-Jung & Lee Seunghun, ‘Someone led the JIG’s fabrication’],” P’ǔresian, April 3, 2012.

7 Hwang Pangyǒl, I Kyǒngt’ae, Kwǒn Usǒng, ‘Mun chǒngin kyosu intǒbyu 2 ‘puk, kimjǒngil yugo ttae kukpangui ch’ejero umjikilkǒt’,” Omainyusǔ, June 14, 2010.

8 Kukhoisamuch’ǒ [National Assembly Management], Che290-291hoikukhoi(imsihoi), “Ch’onanham ch’mmolsagǒn chinsangjosa tǔkpyǒlwiwonhoi hoiǔirok,” vol 1-4, May 24-June 25, 2010.

9 Paik, Nak-chung. 2011. The Division System in Crisis: Essays on Contemporary Korea..

10 Chǒng Chonguk, “Hankuk taet’ongryǒngjeǔi sǒnggongǔl silhyǒnhagi uihan unyǒng model,” Sǒuldaehakkyo pǒphak 43:3, 266.

11 Pak Wǒnsun, “Kukhoi p’ǔrakch’I sagǒn, sasilin’ga [National Assembly Fraction Case, is it true?],” Yǒksabip’yǒng, fall 1989, 228.

12 Chǒn Kapsaeng, “1960nyǒn kukhoi ‘yangminhaksalsagǒnjosat’ǔkpyǒlwiwǒnhoi’ charyo [Materials on 1960 National Assembly Special Committee to Investigate the Massacres of Civilians],” Chenosaidǔyǒn’gu 1 (February 2007), 253.

13 Kang Pyǒnghan, “Ihan’gu, ‘idonghǔp in’gyǒksalin, tosaljangch’ǒngmunhoi’ saenuriǔi makmal todun,” Kyǒngyang sinmun, January 22, 2013.

14 When the KBS 9 O’clock News reported on April 7, 2010 that Warrant Officer Han Juho died near a “third buoy,” the Ministry of National Defense immediately denied the report and demanded that KBS correct and remove the report from the website, which it did. Navy Headquarters filed a media mediation request against 8 newspapers, and Korea Communications Commission handed down a heavy penalty to the KBS’s Ch’ujǒk60pun [Investigation-60 Minutes] for its program on the Cheonan.

15 The Minister of National Defense accused Pak Sǒnwǒn of spreading false information, the Joint Chiefs of Staff Representative I Chǒnghui of libel, and the Navy’s Sin Sangch’ǒl of a violation of the law on electricity and communication. The police arrested a college student who was distributing flyers raising questions. Conservative groups such as Right Korea, Association of Families of Kidnapped Persons, and Association of Bereaved Families of 6-25 filed a National Security Law violation suit against Kim Yongok, and a violation of the law on electricity and communication suit against 12 bloggers who raised questions on the internet. Right Korea and Agent Orange Victims League accused the PSPD and SPARK of defamation and violation of the National Security Law.

16 Song Minsun, “Ch’ǒnanham, kukkaanborǔl saenggakhamyo,” April 30, 2010.

17 PSPD, “The PSPD’s Stance on the Naval Vessel Cheonan Sinking,” June 1, 2010.

18 Cho Hyǒnho, “Kyoyangp’rogǔraeme kimyunok yǒsa miwha changmyǒn nǒǔra chisi,” Midiǒonǔl, March 27, 2012.

19 Ch’ae Ǔnha, “

20 “Pangt’ongsimǔiwi,

21 Kang Wǒnt’aek, “Ch’agidaesǒn’gwa taebukchǒngch’aek [Next Presidential Election and Policies toward the North],” 2011 T’ongilǔisikchosapalp’yo, Institute for Peace and Unification, Seoul National University, 2011, p. 104.

22 Kang Wǒnt’aek, “Ch’ǒnanham sagǒnǔn chibangsǒn’gǒǔi pyǒnsuyǒnna? [Was the Cheonan incident a factor in the local elections?]” Tongasiayǒn’guwon (EAI) Op’inion ribyu 1, June 22, 2010.

23 Song Yoon-kung, “Most Citizens Do Not Understand the Sinking of the Cheonan.” Kyung-Hyang Daily (April 1, 2010)

24 Kim Ki-hyun, “Ms. Park, the Former Leader of Party, Stays in Her Electoral District.” Dong-A Daily (May 21, 2010)

25 Hong Soo-young, “Park Goes to Security Meeting, Not the Party’s Annual Meeting.” Dong-A Daily (September 2, 2011)

26 Kim Gwang-ho, “Park Will Put More Efforts for Dialogue, Easing Tension with North.” Kyung-Hyang Daily August 23, 2012.

27 Park Min-gyoo, “Ms Park Hope for Meeting with North Korean Leader to Better the Tie.” Kyung-Hyang Daily (November 6, 2012)