21st-Century Yakuza: Recent Trends in Organized Crime in Japan ~ Part 1 21 世紀のやくざ ―― 日本における組織犯罪の最近動向

Andrew Rankin

I – The Structure and Activities of the Yakuza

Japan has had a love-hate relationship with its outlaws. Medieval seafaring bands freelanced as mercenaries for the warlords or provided security for trading vessels; when not needed they were hunted as pirates.1 Horse-thieves and mounted raiders sold their skills to military households in return for a degree of tolerance toward their banditry.2 In the 1600s urban street gangs policed their own neighborhoods while fighting with samurai in the service of the Shogun. Feudal lords paid gang bosses to supply day laborers for construction projects. In the 1800s gambling syndicates assisted government forces in military operations.3 Underworld societies joined with nationalists to become a significant force in politics. For many years police colluded profitably with pickpocketing gangs before being ordered to eliminate them in a nationwide crackdown of 1912.4 In the 1920s yakuza bosses were elected to the Diet.5 In the postwar era police struggled to control violent street gangs. Business leaders hired the same gangs to impede labor unions and silence leftists. When Eisenhower planned to visit Japan in 1960, the government called on yakuza bosses to lend tens of thousands of their men as security guards.6 Corruption scandals entwined parliamentary lawmakers and yakuza lawbreakers throughout the 1970s and 1980s. One history of Japan would be a history of gangs: official gangs and unofficial gangs. The relationships between the two sides are complex and fluid, with boundaries continually being reassessed, redrawn, or erased.

The important role played by the yakuza in Japan’s postwar economic rise is well documented.7 But in the late 1980s, when it became clear that the gangs had progressed far beyond their traditional rackets into real estate development, stock market speculation and full-fledged corporate management, the tide turned against them. For the past two decades the yakuza have faced stricter anti-organized crime laws, more aggressive law enforcement, and rising intolerance toward their presence from the Japanese public.

1991 saw the introduction of the Anti-Yakuza Law, which imposed tight restrictions on yakuza activities, even to the extent of deeming some otherwise legal activities to be illegal when performed by members of blacklisted gangs.8 A multitude of additions and amendments have followed, most recently in 2008. Other relevant new laws have included the Anti-Drug Provisions Law (1992), the Organized Crime Punishment Law (2000), and the Transfer of Criminal Proceeds Prevention Law (2007). These last two target yakuza profits by suppressing financial fraud, money-laundering, and transnational underworld banking. The Criminal Investigations Wiretapping Law (2000) increased the range of surveillance methods available to investigators of gang-related cases. So-called Yakuza Exclusion Ordinances, implemented at prefectural level across Japan between 2009 and 2011, aim to ostracize the yakuza even further by penalizing those who cooperate with them or pay them off.

The ‘ultimate symbiosis’ between the yakuza and the police that Karel van Wolferen described in 1984 does not endure today.9 Police hostility to the yakuza has intensified, with more raids of yakuza offices and yakuza-run businesses, more arrests of senior rather than street-level gangsters, and more confiscations of illicit yakuza profits. ‘Yakuza eradication’ has become popular policy, with politicians, governors, mayors, and lawyers’ associations all proclaiming their resolve to destroy the yakuza once and for all. Anti-yakuza campaigning has recently extended beyond the traditional yakuza world to address a broader sphere of activities deemed to be undesirable or antisocial.

However, difficulties in defining the intended targets of these countermeasures, along with a tendency to link organized crime to minority groups or ethnicity, have led some commentators to wonder whether things have gone too far. The Japanese media reports resistance to burgeoning police powers and concern that some new anti-yakuza legislation may prove harmful to legitimate businesses. The 21st-century yakuza must also deal with competition from organized gangs of non-yakuza criminals and from foreign crime gangs active in Japan. Before examining these issues, let us first take a broad look at the state of organized crime in Japan today.

Yakuza membership and infrastructure

The Anti-Yakuza Law constrains and obstructs the yakuza, but does not ban them altogether. Yakuza membership is still not illegal. Unlike Sicilian mafia bosses and Mexican drug lords, yakuza bosses are not fugitives from the law. The addresses and telephone numbers of the major gang headquarters are publicly available. Underworld gossip is reported and analyzed in the popular Japanese press in much the same way as showbiz gossip. The legitimate status of Japan’s organized crime gangs continues to be one of their most distinctive features.

This legitimacy, together with some of the well-known peculiarities of yakuza culture, has earned the yakuza a high degree of international recognition that is arguably disproportionate to the scale of their activities today. A recent study of transnational organized crime devotes a chapter each to the Columbian drug cartels, the Italian Mafia, the Russian Mob, the Japanese yakuza, and the Chinese triads.10 But another distinctive feature of the yakuza is their insularity. Unlike those other organizations the yakuza have not established vast transnational criminal networks; they do not export drugs to the world, or sell weapons to terrorist groups, or threaten national security with anarchic violence. Though they have adjusted their methods and operations with great inventiveness over the decades, essentially the yakuza remain localized extortionists and enforcers, their rackets confined almost entirely to Japan.

According to statistics compiled by the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) and the National Police Agency (NPA), the core yakuza population has been decreasing steadily since the mid-1960s. This decrease has accelerated in the new millennium: in 2010 the total number of full-time and part-time members of yakuza gangs known to police fell below 80,000 (to 78,600) for the first time in fifty years.11 Since 2005 the number of part-timers (42,600) has exceeded the number of full-time gang members (36,000). Note, however, that this is only the number of known yakuza operatives. As explained below, there are reasons to suspect that an increasing number of unknowns are becoming active.

Western journalists who write about the yakuza often state that the yakuza population is many times the strength of the American Mafia at its peak.12 This is misleading, as it implies that organized crime is a bigger problem in Japan than in the US. In 2011 the FBI estimated the total US crime gang membership at 1.4 million, nearly twenty times the size of the yakuza, and while US crime gangs differ structurally and operationally from yakuza gangs in many ways, their principle activities (robbery, drug and gun trafficking, fraud, extortion, prostitution rings, etc.) are in Japan firmly within the yakuza domain.13 The size of Japan’s crime gang population is comparable with that of western European nations: in Italy and the UK, each of which has a population half that of Japan, organized crime gang membership is estimated at 25,000 and 38,000 respectively.14

The largest yakuza gangs in Japan today include: the Yamaken-gumi (based in Kobe, with an estimated membership of 7,000), the Kōdō-kai (Nagoya, 4,000), the Sumiyoshi-ikka (Tokyo, 2,200), the Takumi-gumi (Osaka, 1800), the Kōhei-ikka (Tokyo, 1,600), the Matsuba-kai (Tokyo, 1,200), the Kyokutō-kai (Tokyo, 1,100), the Kokusui-kai (Tokyo, 1,100), the Yokosuka-ikka (Kanagawa, 900), the Iseno-kai (Saitama, 900), the Dōjin-kai (Fukuoka, 850), the Katō Rengō-kai (Tokyo, 800), the Kudō-kai (Fukuoka, 630), the Kyokushin Rengō-kai (Osaka, 600), the Shōyū-kai (Osaka, 600), the Ōishi-gumi (Fukuoka, 600), the Kobayashi-kai (Tokyo, 600), the Kōgomutsu-kai (Tokyo, 500), the Kokusei-kai (Osaka, 500), the Aizu Kotetsu-kai (Kyoto, 410), the Shinwa-kai (Tochigi, 400), the Kyokudō-kai (Hokkaido, 350), the Kokuryū-kai (Okinawa, 300), the Sōai-kai (Chiba, 270), the Kōryū-ikka (Fukushima, 250), the Asano-gumi (Fukuoka, 230), the Tashū-kai (Fukuoka, 180), the Kyōdō-kai (Hiroshima, 170), the Gōda-ikka (Yamaguchi, 160), the Sakaume-gumi (Osaka, 160), and the Kozakura-ikka (Kagoshima, 100).15

As is typical of Asian crime gangs, yakuza gangs join together in large syndicates. In Japan there are three main syndicates: the Yamaguchi-gumi (headquartered in Kobe and comprising several hundred gangs around Japan with a total membership of around 34,900), the Sumiyoshi-kai (Tokyo, 12,600), and the Inagawa-kai (Tokyo, 9,100). The dominance of these three syndicates has grown steadily since the 1970s and today they account for nearly three-quarters of the yakuza population.16

Bosses of some of the major Yamaguchi-gumi gangs. |

The Yamaguchi-gumi currently maintains amicable relations with the Inagawa-kai syndicate, and with more than half the other blacklisted gangs; the gangs share information, conduct occasional joint ventures, loan each other territorial privileges, and try to avoid conflict. In effect this means that the Yamaguchi-gumi now has some sort of access to around 90% of the whole yakuza infrastructure. Law enforcement agencies have accordingly focused their recent investigations on gangs affiliated to the Yamaguchi-gumi, particularly the big gangs in western Japan. The Tokyo-based Sumiyoshi-kai, arch enemy of the Yamaguchi-gumi, has become rather isolated, though it has a longstanding alliance with the Kudō-kai in Fukuoka, another gang hostile to the Yamaguchi-gumi.

All the organizations named above are among the 22 gangs and syndicates blacklisted under the Anti-Yakuza Law. But not all yakuza gangs are blacklisted: more than fifty gangs currently operate free from the Anti-Yakuza Law restrictions. Most of these gangs are small, with fewer than 100 members, and have won exemption by ensuring that the proportion of their membership with a criminal record never rises to the level at which the Anti-Yakuza Law would become applicable. These gangs strive to maintain peaceful relations with their local communities, confine their activities to small-scale traditional rackets, do not carry guns or sell drugs, and generally keep a low profile. Non-blacklisted yakuza gangs currently active include the Matsuura-gumi (based in Kobe), the Kumamoto-kai (Kumamoto), the Tachikawa-kai (Fukuoka), the Kaneko-kai (Yokohama), the once powerful Tōa-kai (Tokyo), and the tiny Takenaka-gumi (Shizuoka).

Trends in yakuza activity

The yakuza pursue money and power through extortion, intimidation, fraud, corruption, and a remarkably diverse range of criminal or near-criminal activities. Their main businesses are basically the same as those of crime gangs everywhere: drug-dealing, smuggling, prostitution, gambling, and protection rackets. The two most serious threats that the yakuza pose to Japanese society today are their potential to disrupt the mainstream business world through corporate frauds and extortion rackets, and their harassment of the general public through loan-sharking, aggressive debt-collecting, interference in civil disputes, and scams of all sorts.

Two trends in yakuza operations are apparent: a shift from traditional rackets toward white collar crime, and a shift from consensual activities (such as gambling and prostitution) toward more predatory activities (such as loan-sharking and theft). While the latter problem is responsible for turning public opinion against the yakuza, it is concern about yakuza infiltration of the business world, and of the finance sector in particular, that has been the primary galvanizing factor behind the anti-yakuza measures implemented over the last two decades. Yakuza activity in the corporate world will be discussed in detail below.

|

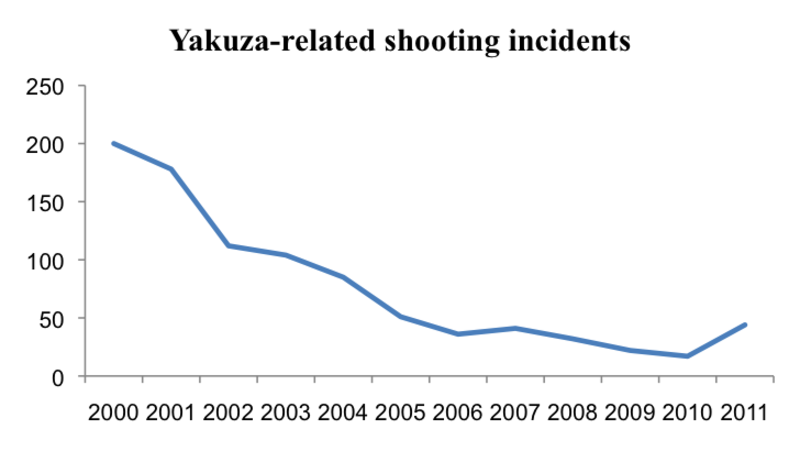

Perhaps the most unusual feature of Japanese organized crime today is that it is not increasing. During the past ten years or so most categories of organized criminal activity have either remained static or exhibited a slight decline. Given the greater secrecy of recent yakuza operations, discussed below, some of these declining figures must be viewed with caution. Nonetheless, there is no statistical data to show that organized crime in Japan is increasing. This fact alone sets Japan apart from almost all other developed nations, where organized crime is on the rise. In Japan, based on the number of yakuza gang members arrested and the number of yakuza-related crimes reported, the first decade of this century has seen declines in cases of intimidation, extortion, embezzlement, blackmail, illegal pornography, destruction of property, obstruction of public officials, arson, kidnapping, injury, rape, and murder committed by yakuza gang members. The crime categories where yakuza activity is increasing include drug-related offences, illegal money-lending, forgery, fraud, and theft.

It is no secret now that many yakuza are short of money, especially those at the bottom end of the yakuza hierarchy. The prolonged stagnation of the Japanese economy has hit some parts of the yakuza industry hard, and like mainstream businesses the gangs have had to streamline their operations, hence the slowly shrinking full-time yakuza membership. In 2009 one ex-yakuza told a journalist that roughly one-third of the middle-ranking men in his gang had been laid off for failing to pay their monthly dues.17 The press has run numerous stories about aging yakuza who live in poverty after being dismissed from their gang. Many gangs are currently on the move, looking for smaller and cheaper office space in order to cut costs.

But at the same time as they are dismissing low-earning older members, the yakuza are facing a manpower shortage. Many of the city-based gangs in particular are finding it harder to recruit new members. With some gangs clearly in financial straits, the yakuza lifestyle is a lot less attractive than it used to be. Joining a yakuza gang can mean hard work and little income, at least for the first few years. As social commentators frequently opine, Japanese youngsters today are less willing to submit to such hardships. Young Japanese men who might once have joined a yakuza gang are now opting for legitimate and more profitable jobs on the periphery of the underworld, as touts, bar hosts, managers of call-girl agencies and massage parlors, or in the pornography industry and the seedier parts of the entertainment industry. Some are establishing gangs of their own and trying to make money from online scams and credit card fraud, or by growing and selling cannabis. Since the entire yakuza industry is predicated on an ability to wreak decisive violence, a shortage of tough young men will seriously reduce the effectiveness of yakuza operations. Indeed, as will be described below, there are signs that this is already happening.

Traditional yakuza rackets

The original yakuza were gamblers, and the modern yakuza continue this tradition. While old-style yakuza gambling games are not extinct, baccarat and other casino-style games have become the norm. A dice game called tabu is currently very popular with gamblers in the Kansai area. Unlicensed slot machine arcades, where the machines offer payouts many times the legal limit, are hidden away in the back streets of most entertainment districts; yakuza gangs run the arcades directly or control them with protection rackets. Yakuza bookmakers take the majority of the bets on horseracing, bicycle racing, and speedboat racing.

On a busy night a yakuza gambling pit can take total bets exceeding ¥100 million, with 5% of each bet going to the gang: an easy profit of ¥5 million. With Japan mired in the economic doldrums, however, the gambling pits are suffering. Moreover, while police used to turn a blind eye to yakuza-run casinos and betting rings in return for underworld information, recently they have been cracking down heavily. A standard yakuza countermeasure is to hire a civilian as a ‘fake’ manager, to be sacrificed to the police in the event of a raid; the gang pays the fine incurred and, if necessary, pays the man to do jail time. Due to this practice, the police crackdown on yakuza gambling pits has not substantially increased the number of yakuza arrested for gambling offences; the damage done to the yakuza is in the loss of revenue and the rise in running costs. Some of the smaller gangs have simply gone bust. The Nibiki-kai, a gang of notoriously pugnacious gamblers based in Hachiōji, disbanded for lack of funds in 2001 after more than thirty years in business.

Due to these severe economic conditions, illegal gambling in Japan has become very corrupt. Cheating is rife on both sides of the table. Some casinos are now elaborate fraud operations, known in the underworld as ‘killing rooms’ (koroshi-bako), designed to fleece the super-rich. Everything about the casino is fake: the staff and the other ‘clients’ are all in on the scam, and the dealers are professional swindlers. Hostesses at nearby bars get potential targets drunk and lead them to the casino. In November 2011 Ikawa Mototaka, chairman of Daio Paper, resigned after he was found to have used ¥10 billion of company funds to cover personal gambling losses. Ikawa initially claimed that he had lost the money at casinos in Macau and Singapore. It did not take the tabloids long to find out that he had been a regular in the killing rooms of Roppongi and Kabukichō.18

In 2010 only 122 yakuza gang members were charged with offences relating to prostitution.19 This figure by no means reflects the extent of yakuza involvement in Japan’s commercial sex industry. Prostitution in Japan is a more diverse, competitive, and multiethnic business than it once was, and there are many ways for the yakuza to profit from it. Yakuza gang members generally avoid street-level pimping, though not always: a member of the Matsuba-kai was recently arrested in Tokyo for running a prostitution ring of 30 teenage girls; the gangster had been delivering the girls to hotel rooms at a charge of ¥20,000, from which he took ¥5,000 for himself, and had made nearly ¥6 million in eight months.20 More usually yakuza are involved in prostitution at the organizational level. This can entail finding and securing premises, forging documents to help human-trafficking gangs bring girls to Japan, and trying to cut deals with the police not to raid the brothels.

During the 1990s there was an exodus of Taiwanese to Japan, and brothels (disguised as massage parlors etc.) were heavily populated with Taiwanese girls. Today the Taiwanese have gone, and their places have been taken by women from other parts of the world, particularly South America and Eastern Europe. Korean women are also very popular in Japan’s sex industry, and traffickers can charge as much as ¥1 million for sneaking a girl into the country. Since drugs are often trafficked along with people, yakuza drug-traffickers are usually heavily involved in these operations.21

While the yakuza continue to dominate entertainment districts with protection rackets, they have been forced to lower their protection fees (mikajime). In Tokyo in the mid-1990s it was not unusual for brothels and mahjong parlors to pay ¥1 million a month to the yakuza. No one pays that today. Brothels now pay around ¥10,000 for each room, and few have more than fifteen rooms. Most small hostess clubs and karaoke bars are now paying about ¥150,000 per month; larger clubs may pay up to ¥500,000. The internet has triggered a proliferation of online call-girl agencies, a service which the Japanese mysteriously call ‘delivery health’. These are more difficult for the yakuza to monitor and control. A Yamaguchi-gumi gangster recently arrested in Shibuya had been taxing an illegal call-girl agency ¥40,000 per month. The owner of the agency, who was also arrested, explained himself to police with flawless underworld logic: ‘If I argue with the guy he’s gonna hassle me, and anyway if I don’t pay this guy some other yakuza guy will ask me for money, so what’s the difference?’22

In media interviews many yakuza complain that it has become more difficult to collect protection payments in the entertainment areas; bar owners are now more likely to dodge payments, haggle for reductions, or call the police. Outside the commercial sex industry and the entertainment areas, in particular, yakuza are finding stronger resistance from business owners and shopkeepers to their demands for kickbacks and protection fees.

Yakuza protection rackets are not always bogus. The custom among Japanese business owners of forming monopolistic guilds or entering into collusive price-fixing agreements, for instance, can easily generate a demand for effective yet unofficial enforcers. However, the hardening of public attitudes toward the yakuza in recent years suggests that more and more Japanese now see the yakuza as extortionists rather than as authentic protectors. Yakuza harassment of the public is a fairly serious social problem: during 2010 nearly 37,000 people contacted police or their local ‘yakuza eradication center’ (bōtsui sentā) in regard to yakuza-related difficulties. The most common complaints related to aggressive debt-collecting and various kinds of extortion attempts; the latter were usually disguised as attempts to sell items that the victim did not want or need, or as demands for compensation in regard to fabricated grievances.23

Some gang members who are desperate for cash have resorted to ‘ignoble’ types of crimes not traditionally associated with the yakuza, such as shoplifting, mugging, burglary, robbery, and pick-pocketing.24 Significantly, the old yakuza word tataki, meaning a ‘heist’, has recently made a comeback. A Yamaguchi-gumi gangster was among those arrested for an extremely violent robbery at a pachinko hall in Hachiōji in December 2009, and a Sumiyoshi-kai gangster has been arrested in connection with the robbery of a jewelry store in Tochigi in August 2011, in which the thieves beat one employee unconscious and broke another’s leg.25 In December 2011 two young Sumiyoshi-kai gangsters were among four men arrested for robbing the office of a company in central Tokyo; the robbers tied up a 68-year-old female employee, frightened her into telling them where the company safe was hidden, and made off with ¥3 million in cash and valuables.26 Reports of such crimes destroy the credibility of the yakuza claim that they try not to bother civilians, if indeed it was ever credible. In some other cases the pettiness of the crime suggests financial hardship. The 61-year-old boss of a gang in Kyoto was recently arrested for stealing wallets from lockers at a public bathing house, and in Sapporo a 71-year-old ex-yakuza was arrested for shoplifting four tins of beans (total value: ¥600) from a supermarket.27

The outstanding tataki of this century so far was the robbery of the Tachikawa office of security firm Nichigetsu in May 2011. Two men beat a guard to gain access to the firm’s vault and escaped with ¥600 million in cash, the largest cash robbery in Japanese history. Police have arrested twenty people in connection with the case. The mastermind appears to have been a senior gangster in the Yamaguchi-gumi, but neither of the men who actually carried out the robbery knew him personally and only one other conspirator had a yakuza connection. The robbers were only identified when one of the conspirators, a former Nichigetsu employee who had given them inside information, lost his nerve and confessed to the police. Police have retrieved less than half the stolen cash; the rest is no doubt in the hands of the Yamaguchi-gumi.28 Constructing a network of disposable civilians in this manner, so as to orchestrate the crime while maintaining distance from it, is becoming a common yakuza tactic, and needs to be taken into account when assessing NPA organized crime reports, which list only the arrests of known yakuza gang members.

Yakuza and politics

Yakuza influence in national politics has all but evaporated. For much of the last century the yakuza worked as enforcers for political parties, pressuring voters and silencing leftists with intimidation and violence. But the use of physical force in the Japanese political arena has declined greatly since the 1960s. Money has replaced violence as the primary means of coercion. Since the political scandals of the 1970s the Japanese public has grown intolerant of politicians who associate with yakuza. The slightest hint of an underworld connection can now be disastrous. One of the factors that led to the resignation of Prime Minister Mori Yoshirō in 2002 was the revelation that he had attended a wedding at which a yakuza boss was also present. There was no suspicion of corruption; the mere fact that Mori had been in the same room as the gangster was deemed inappropriate.29 If the yakuza still play an influential role as enforcers and mediators in local government affairs they are concealing their activities remarkably well. Investigative reporters who hunt for such scandals have unearthed little of substance in recent years.

The most common type of yakuza-related scandal involving politicians at both local and national level is the revelation of small political donations from yakuza-tainted sources. The tabloids have taunted Kokumin Shintō (People’s New Party) leader Kamei Shizuka about his alleged underworld connections since 2003, when it was revealed that a yakuza moneylender had donated ¥500,000 to Kamei’s election campaign; the fact that Kamei is a former policeman gives the story a bit of extra spice.30 In November 2011 a member of the Kagoshima Prefectural Assembly was found to have received a donation of ¥600,000 from a construction firm with strong ties to a yakuza gang.31 In January 2012 police investigating a yakuza-tainted businessman in Chiba discovered that he had made donations totaling ¥1.5 million to the office of Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko. The stock response of politicians to such revelations is to deny knowledge of the donator’s yakuza connection, apologize all the same, and return the money. In Noda’s case, a spokesman for the prime minister told reporters that the money was being returned ‘not out of legal obligation, but for ethical reasons’.32

A 2011 nationwide survey of yakuza harassment of local government officials yielded some encouraging results: 84% of respondents said that they had never received an ‘improper demand’ (futō yōkyū: a generic euphemism for intimidation, bribery, and extortion attempts of all kinds) from a yakuza-connected group or person. Among the 16% who had, the most common complaint was harassment in relation to welfare benefits, public works projects, permits of various kinds, and compensation claims. Many officials also complained of receiving improper demands for release of personal information relating to local residents; these would probably be from yakuza money-lenders, who are often hunting for absconded debtors. Respondents identified the most typical forms of harassment as ‘use of threatening language and demeanor’, ‘thuggish behavior such as slamming the desk or throwing an ashtray’, ‘persistently coming to the office’, and ‘refusing to leave’ (NPA 2011e:3).

The Yamaguchi-gumi was rumored to have pledged its support for the Democratic Party of Japan during the upper house elections of 2007 and in the general election of 2009. If so, it did the gangsters no good: an amendment to the Anti-Yakuza Law in 2008 had immediate and costly consequences for gang bosses everywhere, and after the DPJ’s landslide win in 2009 police arrested more senior Yamaguchi-gumi executives in 12 months than they had done in the previous five years combined.33 The barrage of anti-yakuza legislation passed in the last two decades highlights the political impotence of the yakuza. Veteran yakuza-watcher Mizoguchi Atsushi complains that foreign journalists exaggerate the power of the yakuza in Japan today and insists that the 21st-century yakuza are crime gangs with ‘almost no’ political influence.34 Yet yakuza-run right-wing groups are as noisy and unpleasant as ever, and acts of yakuza violence towards political figures do still occur. In 2000 a disgruntled businessman paid gangsters to firebomb the country home of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, which they did repeatedly.35 In April 2007 a gangster shot and killed the mayor of Nagasaki, Itō Icchō, apparently in frustration that a construction firm had failed to win a public works project despite having donated money to the mayor’s reelection campaign.36 In December 2010 a politically-minded gangster in Ibaraki drove a freezer trailer through the wall of a local assembly election office, killing one person.37

April 17, 2007: Police restrain a yakuza gunman seconds after he shot the mayor of Nagasaki |

Yakuza in the construction industry

The yakuza have a long history of involvement in Japan’s construction industry. Various well-known factors and conditions create roles for them: the common practice of leaking governmental budgets for public works, the extensive powers wielded by bureaucrats, the high cost of bureaucratic mediation in construction projects, the demand for a cheap and obedient labor force, and chronic bid-rigging. As with protection rackets, yakuza operations in the construction industry cannot always be classified as extortion, and sometimes constitute the provision of legitimate enforcement and policing services welcomed or requested by client companies.

In 2007 the NPA conducted a survey of 3,000 construction firms on yakuza activity in the construction industry. Asked if they had received an improper demand from a yakuza-connected contractor within the past 12 months, only 5.7% of respondents said that they had; however, 34% said that they had received an improper demand from persons claiming to represent minority rights or social activist groups, both classic yakuza camouflages. The most surprising result was that two-thirds of respondents said they had not heard about any links between construction firms and yakuza gangs in their area within the last five years. Police welcomed these findings as indicating a decline in yakuza activity. The survey is surely flawed in that it does not recognize the possibility of non-extortionate yakuza activity.38 In any case a survey is not an investigation, and if the yakuza still have their claws into one-third of Japan’s construction industry, the potential for collusion and corruption remains enormous.

Up until the early 1990s it was not unusual for yakuza gangs to own and operate their own construction firms. Since then, stricter monitoring procedures have made it much more difficult for construction firms with known yakuza connections to win contracts for public works, and reports of yakuza-tainted firms being removed from the pool of designated bidders are frequent. Roughly half of the shooting incidents in Japan during 2011 occurred at construction companies: a construction company president in Fukuoka was murdered in November that year, and in January 2012 the deputy chief of the Fukuoka branch of the Federation of Civil Engineering Unions was gunned down outside his office. Analysts believe that this violence reflects yakuza frustration at the strengthened resolve of construction firms not to collude with them or pay them off.39

Accordingly, the yakuza have begun to focus more energy on different but related activities, such as demolition work, debris-removal, asbestos-removal, and waste disposal. These kinds of operations are subject to regulations relating to company licenses, safety measures, training for workers, permits to dump waste, and so on, all of which drive up the cost. Yakuza operators cheerfully ignore these regulations, often employing foreign migrant workers, who may be uninformed about the dangers of handling asbestos, and dumping potentially toxic waste illegally in remote rural areas. The yakuza firm can thus offer the same services as a legitimate firm, but at knockdown prices. Though no data is available, analysts say that the yakuza are more active than ever in these sorts of operations and that police are doing little to stop them.40

Yakuza response to the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami

After the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami of March 2011, yakuza from around Japan hurried to the stricken region with truckloads of emergency supplies. Their various good deeds, widely reported by news media, consciously imitated those of legendary outlaws of the past, such as Kunisada Chūji, a gambler who is said to have distributed food to starving villagers during the Tenpō Famine (1833-1838).41

We must not be so cynical as to discount the possibility that many yakuza genuinely wished to offer assistance and support after a catastrophic national tragedy. But there were also pragmatic reasons for gangsters to make the journey to Tōhoku. Firstly, the relief effort offered the yakuza a rare opportunity to show themselves in a good light, and thereby try to curb public hostility toward them. Perhaps people are less likely to report an improper demand, or call the anti-yakuza squad, or complain to their local yakuza eradication center, after hearing about acts of yakuza charity. Secondly, after destruction comes construction: plenty of money was sure to be made, both legally and illegally, from the cleanup effort and the vast rebuilding projects that would follow.

Fukushima had just passed its yakuza-exclusion ordinance earlier that month. But in the aftermath of the disaster there was little time to check the credentials of those applying for work, or emergency aid, or debris-removal contracts. The Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) did not announce the implementation of procedures to weed out yakuza operatives until mid-July.42 Long before then, yakuza labor-brokers (who call themselves tehaishi: ‘arrangers’) had gathered large numbers of workers for the cleanup effort.

There is no inherent scam in yakuza labor-brokering. In theory, the broker negotiates the wages with the industry recruiter, deducts a commission, and gives the rest to the laborer. In practice, labor-brokering is notorious for its deceptions and swindles – by everyone involved, not just the brokers. Recruiters typically dislike yakuza brokers because they push for higher wages, while police have traditionally ignored the whole situation since the yakuza keep the laborers orderly and docile. At Fukushima Nuclear Plant No.1 there was an urgent need for large numbers of men willing to work under extremely hazardous conditions. Rumors of very high wages at Fukushima spread round the Airin labor market in Osaka, and although anti-nuclear activists urged laborers not to go, many men eagerly followed the yakuza brokers. By early April there were 3,000 men inside the plant on any day, some working on very short contracts to minimize radiation exposure; many more men arrived during subsequent weeks and the cleanup force was thus constantly replenished. It is not known how many of these men arrived via yakuza brokers: one journalist suggests 10%.43 Yakuza brokers secured wages of ¥80,000 a day for men working inside the plant; there were reports that some men were paid over ¥200,000 a day.44

NHK reporters interviewed a yakuza broker who had supplied laborers to Fukushima No. 1. He explained, ‘There was nothing to it: we just picked up guys off the street and drove them to the plant’.45 The broker, who regularly supplied laborers to Fukushima, and also to nuclear plants in Fukui and Ehime, said that he would normally make around ¥80,000 a month off each man he supplied to Fukushima. After March 11 he claimed he was making ¥1.5 million a month off each man.

Although strict registration and monitoring systems for personnel are normally in place at nuclear power plants, at Fukushima No. 1 workers were able to enter and leave without photographs on their ID cards. Laborers supplied by unlicensed yakuza brokers mingled with those from legitimate subcontractors, and no one seemed to notice or care. A TEPCO subcontractor who admitted hiring laborers from yakuza brokers told NHK that skilled employees were kept in safe areas while unskilled laborers brought in by the yakuza were sent straight to the most dangerous spots: ‘It was a battle against time and we needed all the men we could get….The radioactive debris had to be cleared away before anything else could be done. There was no other option: we had to think of those workers as disposable’.46 He suggested that this arrangement was advantageous to TEPCO, since laborers trucked in by the yakuza tend to be the sort of men who disappear from the records. Sure enough, the NHK team confirmed that the whereabouts of 143 men who worked inside the plant between April and June were unknown.

Reports of other yakuza activities around Tōhoku were a mixture of good and bad. Gang bosses in areas as far away as Kyushu and Okinawa sent food and emergency supplies. Many of the yakuza teams that journeyed to affected regions arrived long before official aid agencies, and yakuza supply lines ran with impressive efficiency. Unable to use mobile phones or other communications networks, the gangsters quickly set up a runner system that enabled them to gather lists of supplies needed in each neighborhood and to deliver the requested supplies immediately from the nearest unaffected area. In Ishinomaki, one of the towns worst hit by the tsunami, men believed to be gangsters handed out envelopes, each containing ¥30,000, to survivors; however, the theatricality of this stunt led to some complaints.47 A freelance journalist who worked undercover at the No. 1 plant insists that three yakuza (or possibly, recently retired yakuza) were among the heroic ‘Fukushima Fifty’.48 Less heroic yakuza moneylenders visited the evacuation shelters on the lookout for new clients.49 A gang in Chiba rounded up groups of local homeless men, drove them to the stricken areas and showed them how to apply for emergency financial aid; by applying at multiple locations each man was able to claim up to ¥750,000, of which the gangsters took half.50 A yakuza team of corporate blackmailers was spotted in Fukushima taking measurements with Geiger counters, presumably to collect data for future extortion schemes and compensation claims.51 Many people around Tōhoku made payments to a fake online firm claiming to sell radiation gauges, which never arrived.52 Some gangsters simply intimidated victims into handing over their financial aid.53

Police have so far asked 260 yakuza who received aid to return it, and have arrested a dozen or so for ‘fraudulently applying for and receiving emergency aid’.54 Since members of yakuza gangs were banned from receiving aid under any circumstances, the ‘fraud’ in at least some cases may be only that the men applied for and received aid. The underlying assumption here (that applications from yakuza are sure to be fraudulent while applications from non-yakuza are sure to be authentic) seems questionable. The Sumiyoshi-kai and the Inagawa-kai both have sizeable memberships in the Tōhoku region and there is no reason to think that yakuza homes are immune to tsunamis. Similarly, since the Anti-Yakuza Law makes it an offence for yakuza to engage in labor recruitment, police have recently arrested several yakuza labor-brokers and charged them with ‘unlawful recruitment of labor’.55 This is the real function of yakuza labor-brokers: they are hired scapegoats, and any irregularities in recruitment practices that come to light are blamed on them, not on the industry bosses.

Yakuza drug trade

As mentioned earlier, yakuza operations outside Japan are negligible. During the bubble economy of the 1980s the yakuza were active in Australia and around Asia, and in the US there were fears of an imminent yakuza invasion. Nothing of the sort occurred. In the past few years Japanese gangsters have been refused entry to the Philippines, imprisoned for drug-dealing in North Korea, executed for drug-smuggling in China, and shot dead mysteriously in Thailand.56 Yakuza money-laundering schemes are highly sophisticated, and the big syndicates hide their profits around the world. In transnational criminal operations the yakuza tend to serve as financiers, rather than get directly involved. For example, the yakuza are said to pay gangs in South Korea to manufacture amphetamines, often in secret facilities in Thailand and China, and then smuggle it to Japan. Yakuza gangs also cooperate with other Asian crime gangs in trafficking people, pirated software, guns, drugs, and illegal chemicals, to Japan, and in smuggling stolen property (in particular, stolen vehicles) out of Japan for sale abroad. However, independent yakuza operations outside Japan are, as far as is known, limited to very small-scale operations: a few forged passports, some falsified marriage certificates, small quantities of drugs, etc. If yakuza gangs are still organizing overseas sex-and-gambling trips for wealthy Japanese clients, as they used to in the 1980s, none has recently been exposed. Overall, the yakuza have not exhibited anything like the transnational ambitions or capabilities of the Chinese triads, who now dominate the Asian drug- business while maintaining a vigorous presence in Chinese communities around the world.

A recent shipment of Chinese amphetamines confiscated by Yokohama Customs |

One reason for this is that Japan imports almost all of its recreational drugs: yakuza dealers rely for this on drug gangs overseas. The main ports of transhipment to Japan are in other Asian countries, though the drugs may originate further afield. Amphetamine (crystal meth) remains the drug of choice for Japanese junkies, though cannabis, MDMA (ecstasy), and ketamine have also become popular. Yakuza drug-dealers are further restricted by the lack of demand for cocaine and heroin, drugs that have not caught on in Japan. The yakuza are therefore unable to profit from the sort of alliances with South American drug cartels that have enriched organized crime gangs in many other countries.

By international standards illegal drug use in Japan is not widespread: 14,500 people were arrested for drug offences in Japan in 2010, and nearly half of these were yakuza gang members arrested for possession or dealing.57 However, the very high street-level price of drugs in Japan (often 150-200 times the price at origin) means that drug-dealers can reap large profits from relatively small quantities. Hence yakuza drug-smuggling operations are often modest in scale. Two members of a gang in Nara recently arrested for drug-smuggling had mixed cocaine into a paste and applied it to the surface of sheets of paper, which they posted in letters from Argentina to Japan; the total amounted to a mere 600 grams.58 Yakuza gangs have also been known to place online advertisements for international couriers, whom they dupe into carrying small amounts of drugs to Japan. In October 2010 a 71-year-old Japanese woman was arrested at Osaka airport; she had carried 4 kilos of amphetamine from Egypt, apparently unwittingly.59

Most substantial amounts of amphetamine and other drugs enter Japan on foreign ships. To avoid port inspections operatives on the Japanese side head out in small boats to meet the smugglers just off the coastline. The drug-smuggling business appears to be stable, with overall seizure quantities roughly the same as in 2000. In 2010 police made arrests in 188 drug-smuggling cases; in 37 (17%) of these cases at least one yakuza gang member was among those arrested.60

Recently, drug shipments are getting smaller but more frequent; smaller shipments are, of course, more likely to go undetected. The largest ever customs seizures of amphetamines were in the 1990s, and the last major seizure of cannabis was in 2001, when 393 kilos were found hidden in beer cans shipped to Yokohama from the Philippines. Only MDMA, popular with the young Japanese clubbing crowd, is still being seized in large quantities: in 2007 customs found 688,000 tablets concealed in lumber shipped from Canada.61

A Kansai yakuza boss describes a popular smuggling technique as follows: ‘The Sea of Japan is too well-guarded right now to send drugs over by ship. So the guys on the foreign side dissolve crystal meth in water and fill plastic bottles with it; they attach a radio transmitter to a whole bunch of bottles, tie the bottles to a buoy and set them afloat on the night tide. Guys on this side track the signal, find the bottles and pick them up in a boat. That way nothing shows up on the satellites. Then they just boil away the water to leave the powder’.62

The yakuza do not have a monopoly on the drug trade in Japan. Chinese gangs in Japan cooperate with criminal syndicates in mainland China in independent drug-smuggling operations to Japan. Mainland Chinese gangsters were believed to be responsible for 300 kilos of amphetamine discovered on an Indonesian cargo ship in Mojikō Bay in Kyushu in November 2008.63 Iranian, Brazilian, and Philippine gangs in Japan also conduct independent drug-smuggling operations.64 The gangs either distribute the drugs through their own networks or sell them to yakuza distributors. The yakuza in turn often employ foreign nationals as street dealers, Iranians and Chinese in particular. Since Japanese public opinion is intolerant of illegal drugs, the yakuza try to hide their own involvement and give the impression that foreigners are to blame. Drug-dealing is one area of yakuza activity that has recently become busier. One senior gangster explains, ‘Right now every gang is having trouble finding ways of making money, so they’re short of cash…. One sure way of making money is drugs: that’s the one thing you can’t get hold of without an underworld connection’.65

The new century has also seen the rise of non-yakuza-related Japanese drug-dealing gangs, which have their own smuggling connections, or, in the case of cannabis, grow their own product. These gangs must hide themselves not only from police but also from the yakuza, who instantly muscle in on such operations and extort hefty taxes or simply steal the drugs. In January 2012 police arrested a gang of ten men who had been running a ‘drug delivery service’ from a hotel room in Osaka. The well-organized gang, which apparently was not connected to the yakuza, had installed security cameras outside their room and at various spots inside the hotel.66

Yakuza violence

As mentioned earlier, the yakuza are less violent than they used to be. Changing patterns in Japanese society have erased or diminished many opportunities for purveyors of violence. The trades unions are generally docile now; modern labor management has no need for strikebreaking thugs. Private security firms have replaced many yakuza protection rackets. Online dating sites have reduced the usefulness of yakuza pimps. So-called ‘smart crimes’ such as bank transfer fraud succeed without threats of physical violence.

Accordingly, the yakuza generally specialize in non-violent forms of coercion. Yakuza land sharks put pressure on tenants by sending them unpleasant objects in the mail or playing music at uncomfortably loud volume outside their buildings. Yakuza enforcers and blackmailers scrawl obscenities on debtors’ doors or embarrass them at their workplace. Businesses that refuse to pay protection money may have their premises vandalized: emptying the contents of a septic waste truck through a window is a trademark tactic. The yakuza operatives most likely to assault members of the public are debt-collectors, who often assume that their victims will not call the police. In 2010 yakuza gang members assaulted and/or injured roughly 5,000 members of the public, about half as many as in the 1980s.

In the late 1980s the yakuza were responsible for 30% of Japan’s murders.67 Today they are responsible for 15%.68 During the first decade of this century, yakuza gang members and yakuza-connected persons were arrested in connection with an average of roughly 170 murders and attempted murders each year. Almost all yakuza murder victims are civilians: according to the NPA, only 32 yakuza were murdered by other yakuza during the first decade of this century.69 These extremely low figures mean that the yakuza are among the least murderous crime gangs in the world today. The Neapolitan Mafia kills 100 people every year in Naples, a city with a population of less than 1 million, while Canada, which has a population roughly one-third that of Japan, averages 90 gang-related murders every year.70

Gun use by yakuza has declined markedly. This is due to the increased severity of legal sanctions, as many yakuza have acknowledged in media interviews. A 2004 ruling by the Supreme Court ended a long legal battle by the Yamaguchi-gumi and made yakuza bosses liable for certain criminal acts committed by their men, including violations of firearms laws. Yamaguchi godfather Tsukasa Shinobu spent six years in jail after one of his bodyguards was found to be carrying an illegal firearm. Many yakuza bosses subsequently banned the use of guns by their men. In addition, jail terms for gun users have increased. Up until the 1980s yakuza gunmen convicted of fatal shooting were usually serving jail terms of between 12 and 15 years. Three gangsters involved in a fatal gang-related shooting in Hiratsuka in 2009 (see below) received jail terms of 24 to 30 years each, while the gangster who shot the mayor of Nagasaki received the death sentence, though this was later revoked and reduced to lifetime imprisonment.71

|

It is not an easy matter to buy a gun in Japan today, even for yakuza; a special introduction to a smuggling gang is needed. In the 1980s guns were being smuggled to Japan in shipments of as many as 300 guns at a time, principally from the Philippines. By the 1990s seizures had dropped to fewer than 30 guns at a time, and there has been not been a seizure of more than 10 guns since 2006.72 Foreign crime groups active in Japan, such as Chinese and Iranian gangs, have easier access to guns than the yakuza. Guns circulating in Japan today are mostly old and expensive, and often unreliable. The going rate for a Soviet-era Makarov pistol is ¥500,000; Chinese-made copies can apparently be had for around ¥300,000. Grenades and rocket launchers obtained from military bases are also in circulation, but this is mainly because yakuza bosses like to show them off as trophies.

Recent changes to the Anti-Yakuza Law give police the power to close down the offices of gangs they suspect of involvement in intra-gang violence, and make yakuza bosses liable for compensation claims from civilians who are injured, or whose property is damaged, as a result of such violence.. This has made feuding a costly business, and yakuza bosses therefore try hard to keep the peace. One Tokyo yakuza acknowledges the effect of public opinion: ‘If we fight other gangs to the point where it affects civilians, the police and society take a much stricter attitude to us, and that makes it harder for us to run our rackets. Gangs know this, so they’re more careful’ (Nakano 2010:116). Consequently, violence between rival yakuza gangs is rare at the moment, though in the past decade there have been occasional bouts of bloodletting. The section on intra-gang violence in the latest NPA report consists of a single sentence: ‘This year there were no violent incidents involving rival yakuza gangs, a decrease of 1 from the previous year’ (NPA 2011a:12). One shooting incident is usually all it takes to excite Japanese journalists into proclaiming the outbreak of a ‘yakuza war’.

Violence between yakuza gangs has become largely rhetorical: pipe bombs detonated outside rival gang offices, bullets fired into walls, vehicles set on fire. In July 2002 members of a Sumiyoshi-kai affiliate in Gifu expressed their feelings towards a rival Yamaguchi-gumi gang by reversing an 11-ton dump truck through the wall of the gang’s headquarters.73 In 2009 gangsters in Fukuoka similarly used a dump truck to crush a rival gang boss’s car.74 Most disputes between gangs are now settled speedily through arbitration after a few rhetorical flourishes of this kind.

Police investigate a shooting incident at the home of a yakuza boss |

The most violent yakuza gang of this century so far is the Kudō-kai in Fukuoka. The Kudō-kai was responsible for the attacks on the house of Prime Minister Abe. In addition, over the past ten years the gang has vandalized, firebombed, shot at, and thrown grenades into the offices and homes of numerous companies and individuals that have refused its demands. When citizens of Fukuoka organized a group to protest against the Kudō-kai, the gang shot and wounded the chief organizer and threw a grenade into the group’s office. Despite all this, the Kudō-kai has not yet been punished: other than the arsonist in the Abe case, whom the gang voluntarily surrendered to authorities, no member of the Kudō-kai has yet been brought to justice in connection with these attacks.75 When prosecutors tried to put together an extortion case against the gang’s leadership in 2008, all but one of the witnesses soon changed their minds about testifying, for reasons that are easy to guess. For the 2010 trial of two Kudō-kai members charged with murdering a member of a rival gang, the Fukuoka District Court office deemed the danger of jury intimidation to be so great that it entrusted the trial to a single presiding judge, the first case of its kind since the reintroduction of the jury system in Japan in 2009; both men were acquitted all the same.76 On June 22, 2011 Fukuoka police seized 14 illegal firearms, including submachine guns, from an apartment belonging to a member of the Kudō-kai.77 So troublesome is the gang that there is even talk of amending the Anti-Yakuza Law to include a new ‘dangerous gang’ category especially for the Kudō-kai.

The Yamaguchi-gumi

Characteristically, the Kudō-kai refuses to join the Yamaguchi-gumi. But in these hard times many other gangs have opted to submit to the giant syndicate, which now dominates the Japanese underworld. This has been the trend of the past fifteen years or so, as yakuza bosses from around Japan have swallowed their pride and traveled to Kobe to perform the solemn ritual of kyōdai sakazuki (brotherly bonding symbolized by the sharing of a saké cup) with the Yamaguchi-gumi godfather. Thereafter the smaller gang pays monthly dues to the syndicate in return for information, advice (legal and tactical), access to valuable underworld resources, and protection from other gangs – above all, from the Yamaguchi-gumi itself.

The leading gang within the Yamaguchi-gumi at the moment is the Nagoya-based Kōdō-kai. Tsukasa Shinobu, boss of the Kōdō-kai, is godfather of the Yamaguchi-gumi syndicate. The main activities of the Kōdō-kai are gambling, protection, loansharking, and corporate-level fraud and extortion. The gang also runs a more extensive range of legitimate businesses than do most yakuza gangs. The Kōdō-kai is unchallenged in Nagoya, and virtually every bar, club, and restaurant in the entertainment districts there pays protection money to the gang. The leaders of the Kōdō-kai are among the most conspicuous gangsters in Japan. Tsukasa’s chief advisor, Takayama Kiyoshi, whom many in the Japanese underworld revere as a sort of criminal genius, never travels with fewer than eight bodyguards, and when he rides the bullet train scores of his henchmen guard the station. Though this suggests many enemies, Takayama is said to be adept at yakuza diplomacy and is credited with building and maintaining peaceful relations between the Yamaguchi-gumi and rival gangs around Japan that have not joined the syndicate.

Kōdō-kai chairman Takayama Kiyoshi reputedly lost his right eye in a youthful knife-fight |

The Kōdō-kai is said to contain a secret section called the Jūjin-kai, whose members never visit the gang’s offices and are unknown to other gang members. The Jūjin-kai specializes in covert operations such as infiltrating companies and institutions, spying on rival gangs, and gathering information on police detectives and their families to be used for intimidation purposes. Rumor has it that some Jūjin-kai members also receive special training overseas and thereafter work as hitmen, though this may be the gang’s own propaganda.

Strange though it may seem, the Kōdō-kai is highly litigious. The gang has repeatedly challenged new anti-yakuza legislation in the courts, and has brought civil claims against the police. In May 2010 the Kōdō-kai successfully sued the Osaka Police Department after detectives assaulted one of its members during an interrogation. Though the officers responsible went unpunished, a judge ordered the OPD to cover the victim’s medical expenses and legal costs. A week later the NPA Commissioner General announced that his anti-yakuza squads would henceforth be focusing their investigations on the Kōdō-kai. During the next 12 months police arrested more than 1,000 members of the gang, including Takayama Kiyoshi himself, who is now in detention awaiting trial on an extortion charge.78

Gangs in the Kantō region have traditionally been more cooperative with police, and also more cordial to each other, since their shared fear of the Yamaguchi-gumi acted as a powerful bonding agent. This situation changed dramatically in 2005 when the Kokusui-kai, one of Tokyo’s oldest gangs, announced that it was joining the Yamaguchi-gumi. For years the Kokusui-kai had been sharing its territories in Tokyo with the Sumiyoshi-kai, main rival of the Yamaguchi-gumi. These profits now flow to Kobe. Tension between the Yamaguchi-gumi and the Sumiyoshi-kai has been boiling since then. The Yamaguchi-gumi was thought to be behind a series of shootings in central Tokyo early in 2007, in which a Sumiyoshi-kai boss was assassinated.79 If the Sumiyoshi-kai cannot halt the Yamaguchi-gumi invasion, it will eventually crumble and the lucrative Tokyo entertainment districts of Ginza, Kabukichō, Akasaka and elsewhere will be controlled and taxed by men from Kansai.

Yakuza to mafia

Critics of the Anti-Yakuza Law contend that, although the law has been effective in suppressing many yakuza protection rackets, it has triggered a rise in other, more harmful criminal activities. Miyazaki Manabu, an advocate of the rights of yakuza gangs to exist and operate, says, ‘By reducing the range of legal activities available to the yakuza, the Anti-Yakuza Law has actually had the effect of encouraging them to evolve into mafia-like syndicates’ (Miyazaki 2007:349). The Japanese tabloids have devoted considerable space to the ‘mafia-ization’ (mafuia-ka) of the yakuza. The idea is that the gangs have maintained their traditional facades while diversifying their activities and channeling their energies into more covert and insidious crimes. The new breed of gangsters is believed to be virulently rapacious, as indicated by the rise of aggressive loansharking schemes, white collar crimes, robberies, and financial scams that directly target the public. The activities and tactics of the Kōdō-kai, in particular, are said to exemplify this trend.80

The yakuza/mafia distinction is perhaps a dubious one. There is no doubt, however, that the yakuza phenomenon has changed considerably in recent years. Yakuza were once not shy about standing out from the katagi (non-yakuza civilians). Now they strive to blend in. Vernacular changes reflect the new climate of secrecy: common underworld terms today are burakku (black, i.e. not legitimate), yami (shady), ura (hidden) and angura (underground). Aside from the bosses and their security teams, who still like to put on a show, yakuza operatives today generally avoid making their presence known except when they consider it advantageous to do so.

The move towards invisibility has intensified since 2008. Since Japan does not have an organized criminal conspiracy law resembling the US RICO Act, gang bosses cannot be tried for criminal acts they may have ordered or planned. A 2008 amendment to the Anti-Yakuza Law went some way towards remedying this situation by making yakuza bosses liable to civil compensation claims for damage resulting from criminal acts committed by their subordinates. In a landmark case the following year, the owner of a Thai bar in Tokyo brought a law suit against Tsukasa Shinobu, leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi. The bar owner, a Thai national, had been secretly running a gambling ring without paying the traditional dues to her local yakuza gang, a Yamaguchi-gumi affiliate. When a team of gangsters arrived to administer yakuza justice, they assaulted the staff, wrecked the interior of the bar, and made off with fistfuls of cash from the register. Taking advantage of the 2008 amendment, the owner sued Tsukasa for compensation. Defense attorneys argued that Tsukasa could not reasonably be held accountable for the actions of every member of every gang affiliated to his syndicate – a nationwide total of nearly 40,000 men – and that in any case he was in jail at the time of the incident. But the court ruled in favor of the plaintiff and ordered Tsukasa to pay damages of ¥15 million.81

Tsukasa Shinobu, sixth godfather of the Yamaguchi-gumi |

This ruling opened the way for similar cases, and Tsukasa is now bombarded with lawsuits. In February 2011 a court ordered him to pay ¥4 million to the owner of a bar in Gifu who had been assaulted by members of a Yamaguchi-gumi gang after refusing to pay protection money; in June Tsukasa paid ¥42 million to a taxi firm in Hyōgo from which gangsters had attempted to extort money; in July a Nagoya man successfully sued Tsukasa for damages of ¥10 million after having his arm broken by yakuza debt-collectors; and in September Tsukasa had to pay another ¥14 million in damages to a Tokyo man from whom gangsters had extorted money.82 One would think that the most powerful yakuza boss in Japan could easily silence potential plaintiffs with intimidation; apparently he cannot. Tsukasa’s predicament underscores the paradoxical status of the modern yakuza as ‘legitimate crime gangs’. In contrast, foreign crime gangs in Japan, discussed below, and non-yakuza organized criminals (gangs of thieves, drug-dealers, fraudsters, unlicensed money-lenders, etc.) are not subject to the restrictions of the Anti-Yakuza Law, and therefore have an advantage over the traditional yakuza gangs. As one analyst says, ‘Being a yakuza has become an economic liability’.83

The response of the Yamaguchi-gumi since 2008 has been to start dismissing members in even greater numbers than it was already doing: about 2,000 every year. In accordance with standard yakuza protocol, the gang sends details of each dismissed gang member to the police and to other gangs, and requests that they treat him as a civilian henceforth. Police say that the Yamaguchi-gumi is shrinking, and claim a victory. But some analysts suspect that a great many of these dismissals are fake, and that the men are continuing to work covertly for the syndicate or plan to do so in the future.

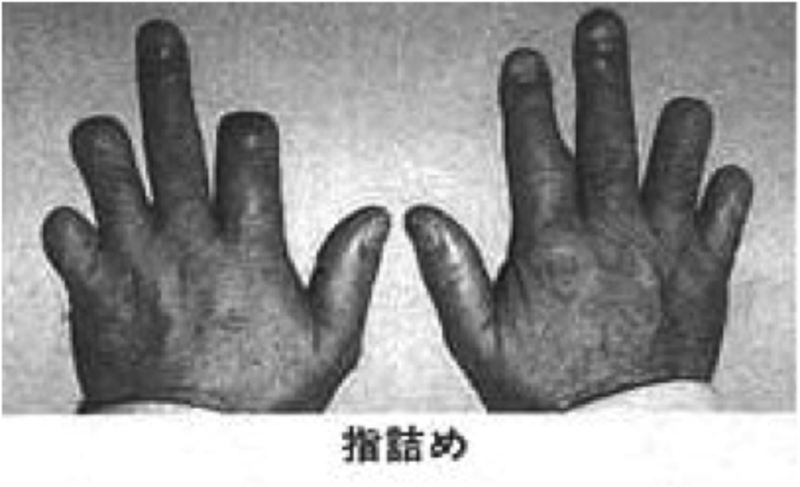

In accordance with this trend towards secrecy and invisibility, some of the most conspicuous aspects of yakuza culture are in decline. The practice of severing a finger joint to atone for mistakes (yubi-tsume) is rare now; head-shaving has taken its place. Yakuza who cut their fingers today mostly do so involuntarily. In October 2008 a young member of a Tokyo gang was bullied into cutting off the little finger of his left hand after he requested permission to leave the gang, and in December 2010 a young member of a Kobe gang was forced to do the same after failing to repay a small loan to one of his seniors. In both cases the victims called the police, who arrested several men and charged them with coercion and intimidation.84 The main form of punishment in yakuza society today is a financial penalty and/or expulsion from the gang.

Yakuza hands, c.1970. Finger-cutting today is rare. |

The rise in popularity of tattoos among Japan’s younger generation means that the tattoo is no longer an exclusive yakuza signifier. In the 1980s the horishi (traditional-style tattoo artists) seemed a dying breed; today they do good business, though their clients are as likely to be club touts and barmen as gangsters. Full-body tattoos are less popular now, especially among yakuza operating in urban areas; many young yakuza limit their tattoos to their upper arms and backs, or do without tattoos altogether. Nonetheless, some recent evidence suggests that the yakuza still take their tattoos seriously. In July 2009 during the Tanabata Festival celebrations in Hiratsuka, a fight broke out after a young member of a Sumiyoshi-kai gang exposed his tattoo in a part of town controlled by the Inagawa-kai. A few hours later he was found dead: he had apparently been kidnapped, tortured, and stabbed with a long blade. A few hours after that, three gunmen attacked the Hiratsuka headquarters of the Inagawa-kai and fatally shot one member. Gangsters from both syndicates were arrested and charged with the murders.85

Yakuza in the corporate world

During the boom period of the 1980s, yakuza muscle reinforced the intimidation tactics of sōkaiya (corporate blackmailers) and jiageya (enforcers hired by real estate developers to persuade landowners to sell their property). Today, however, yakuza are more likely to be involved directly as financial backers for teams of predatory speculators. The so-called kinyuya (corporate moneylenders who accept shares as collateral for abnormally large loans, sometimes lending as much as ten times the value of the shares) often receive financial backing from companies that serve as fronts for yakuza gangs. Other new types of financial racketeers who may have ties to the yakuza include keizai goro (extortionists who offer supposedly valuable investment tips and then make aggressive demands for payment) and yakara (speculators who artificially inflate stock prices in order to reap short-term profits). Financial racketeers conceal their yakuza connections in the first instance but reveal them when needed.

The central role played by the yakuza in poisoning Japan’s banking and financial systems during the 1990s is today a matter of common knowledge, as is the fact that financial regulators colluded with banks and their yakuza clients in concealing bad loans rather than writing them off.86 In 2002 the Resolution and Collection Corp (RCC), the descendant of the former Housing Loan Administration Corp that is now responsible for buying bad loans from the banks, reported that 18% of the loans they had bought so far were yakuza-related. In December 2006 the Tokyo Stock Market and the NPA announced the establishment of a joint committee to eradicate the yakuza from the stock market. Investigators now closely monitor trading accounts, trying to sift out names that they think might have underworld connections.

But it is a challenging task, as one investigator admits: ‘These days it’s very difficult for us to spot the yakuza operators. They disguise themselves as ordinary companies and infiltrate the corporate world in all kinds of ways. On the surface they’re just normal businessmen, making deals like everyone else’ (NHK 2008:86). For camouflage the gangs set up front companies, which do legitimate business, or dummy companies, which do no business at all. The gangs use these companies to build corporate relations, to win credibility with banks, to filter criminal profits into the upperworld, or to evade tax. Front companies enable the yakuza to operate their extortion rackets at corporate level. Having established a business relationship with a legitimate firm, the front company will soon start to act unreasonably, e.g. by demanding large sums of compensation for slight delays or minor oversights. If the other firm resists, the front company hints at or reveals its yakuza identity and adopts a much more threatening attitude. Investigators believe that several thousands of these yakuza front companies are active at any one time, and new ones are constantly appearing, making it almost impossible to monitor them and identify them promptly.87

The yakuza are also engaging in high-level corporate swindles. In March 2008 US investment bank Lehman Brothers was one of several companies that fell victim to fraudsters working on short-term contracts for trading house Marubeni. The fraudsters approached Lehman Brothers and claimed to be seeking funds to provide hospitals with state-of-the-art medical equipment. Lehman Brothers invested $320 million in the equipment, which, it later transpired, did not exist.88 In 2010 police arrested the owner and manager of a Tokyo real estate firm who had used a dummy company to conceal profits of ¥2.6 billion from a sale of property in Ginza. The owner of the firm was exposed as a gang boss in the Inagawa-kai.89

One gangster explained to reporters how much the switch to financial and corporate rackets has transformed the yakuza experience: ‘I once did time in jail for trying to shoot a guy. I’d be crazy to do that today. There’s no need to take that kind of risk any more….I’ve got a whole team behind me now: guys who used to be bankers and accountants, real estate experts, commercial money lenders, different kinds of finance people. Just because I’m a yakuza, that doesn’t mean I can boss them around – they’re more like my advisors. There’s so much you can do with the knowledge these guys have’ (NHK 2008:163-4).

A popular yakuza trick for channeling criminal profits into the finance sector is to recruit homeless people, who are offered an apartment and a steady job in return for the use of their jūminhyō (residence card); with this card the gangsters can open an online trading account in the homeless person’s name and immediately start buying shares. Some yakuza offices today even have a ‘dealing room’ – a room of computers used for stock-trading under multiple fake identities. Journalists gained entrance to a yakuza dealing room manned by a young graduate who was making day-trades to a total of around ¥300 million every day, with an average monthly profit of 10-15%.90 Via this route, illicit profits from extortion and protection rackets, loan-sharking, gambling, and drug-dealing flow smoothly and silently into the stock market from yakuza offices around Japan.

Identifying yakuza operators is one thing; successfully prosecuting them is another. Stock manipulation is extremely difficult to prove under Japanese law and the yakuza have become adept at covering their tracks. In November 2009 Osaka police arrested the head of investment group Union Holdings, together with an eight-man team of speculative traders thought to have extensive underworld connections, on suspicion of various acts of fraud including fictional underwriting and unlawful manipulation of share prices. Prosecutors eventually dropped the case for lack of evidence.91 In February 2010 the CEO of systems-developer Trans Digital was arrested, along with four business partners, and charged with arranging illegal transfers of company assets in which some ¥3 billion had gone missing. Prosecutors alleged, but could not prove, yakuza involvement. All five men received suspended sentences.92

Despite the various countermeasures, then, the situation remains dire. Experts argue that the continuing success of yakuza predators in Japan’s finance sector is at least partly due to deficiencies within the sector itself, blaming greed among speculators and irresponsible measures by the government, such as the repeated issuing of deficit-covering bonds (akaji kokusai). One analyst says, ‘In a stock market like this, which is starting to look like a crazy gambling den where there are no rules or logic of any kind, the yakuza are bound to be the strongest players, since not only do they have plenty of money to invest, they also have a failsafe method of collecting their debts: the threat of violence’ (Matsumoto 2008:222).

Yakuza activity in real estate and land development does not appear to be as rampant at the moment as it was in the 1990s. Nonetheless there are still some high-profile cases. In 2008 it was revealed that construction firm Suruga Corp had hired an Osaka real estate firm, which was really a yakuza front company, to evict tenants from five office buildings occupying land that Suruga wanted to develop. The gangsters used various non-violent intimidation methods to persuade the tenants to vacate the buildings, and collected ¥3.7 billion from Suruga in return. Police charged several employees of the real estate firm with violations of real estate laws, but with no other crime. No one from Suruga was arrested, although the firm’s CEO offered his resignation the day the story broke.93

Andrew Rankin lived in Japan for nearly twenty years and studied at Tokyo University. He is currently in the Japanese Department at Cambridge University, writing up a PhD dissertation on Mishima Yukio’s non-fiction. He is the author of Seppuku: A History of Samurai Suicide (Kodansha International, 2011).

Recommended citation: Andrew Rankin, ’21st-Century Yakuza: Recent Trends in Organized Crime in Japan – Part 1,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 10, Issue 7, No 2, February 13, 2012.

References

Some of the information in this article was obtained discreetly from underworld sources.

Akahata 2004: Shinbun Akahata shuzaihan, Uragane: keisatsu no hanzai (Secret Money: The Crimes of the Police). Shin Nihon Shuppansha.

Botsui senta 2003: Botsui tomin senta, 10-nen no ayumi (Ten years of the Citizens Center for Eliminating Organized Crime). Boryokudan tsuiho undo suishin tomin senta.

Friman 1996: Friman, H. Richard, ‘Gaijinhanzai: Immigrants and Drugs in Contemporary Japan’. Asian Survey, Vol. 36 No. 10, 1996.

Goto 2010: Goto Tadamasa, Habakari-nagara (I don’t mean to be rude, but…). Takarajimasha.

Hill 2006: Hill, Peter, The Japanese Mafia: Yakuza, Law, and the State. Oxford University Press.

Ino 1993: Ino Kenji, Yakuza to Nihonjin (The Yakuza and the Japanese). Gendai Shokan.

Ino 2008: Ino Kenji, Yamaguchi-gumi gairon (A Summary of the Yamaguchi-gumi). Chikuma Shinsho.

Ishida 2002: Ishida Osamu, Chugoku no kuroshakai (The Chinese Underworld). Kodansha.

JC 2009: Japan Customs and Tariff Bureau, Trends in Illicit Drugs and Firearms Smuggling in Japan (2009 Edition). Ministry of Finance.

JFBA 2004: Japan Federation of Bar Associations, Q&A Boryokudan 110-ban: kisho chishiki kara toraburu jirei to taio made (Q&A on Yakuza: from basic knowhow to examples of trouble and countermeasures). Minjiho Kenkyukai.

JFBA 2010: Japan Federation of Bar Associations, Hanshakaiteki seiryoku to futo-yokyu no konzetsu e no chosen to kadai (Challenges and Problems involved in Eradicating Antisocial Forces and Undue Claims). Kinyu Zaisei Jijo Kenkyukai.

Kaplan & Dubro 1987: Kaplan, David E., and Dubro, Alec, Yakuza: Japan’s Criminal Underworld. London: Queen Anne Press.

Kitashiba 2003: Kitashiba Ken, Nippon higoho chitai (Japan’s Illegal Zone). Fusosha.

Koishikawa 2004: Koishikawa Zenji (ed.), Muho to akuto no minzokugaku (Folk Studies on Outlaws and Villains). Hihyosha.

Koizumi 1988: Koizumi Tesaburo, Suri daikenkyo (The Great Pickpocket Crackdown). Tokyo Hokei Gakuin Shuppan.

Limosin 2007: Limosin, Jean-Pierre, Young Yakuza (French-subtitled documentary movie).

Lyman & Potter 2000: Lyman, Michael D. and Potter, Gary W., Organized Crime. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Mandel 2011: Mandel, Robert. Dark Logic: Transnational Criminal Tactics and Global Security, Stanford University Press, 2011.

Matsumoto 2008: Matsumoto Hiroki, Kyoseisha: kabushiki shijo no kuromaku to yakuza mane (Collaborators: Yakuza money and the Dark Side of the Stock Market). Takarajimasha.

Mediax 2008: Rokudaime Yamaguchi-gumi kanzen deta BOOK 2008 nenban. (Complete Data on the Sixth Yamaguchi-gumi in 2008). Mediax.

Miyazaki 2007: Miyazaki Manabu, Kindai yakuza kotei-ron: Yamaguchi-gumi no 90 nen (A Positive Theory of the Modern Yakuza: 90 Years of The Yamaguchi-gumi), Chikuma Shobo.

Mizoguchi 2005: Mizoguchi Atsushi, Pachinko 30-choen no yami (Pachinko: ¥3 trillion darkness). Shogakkan.

Mizoguchi 2011a: Mizoguchi Atsushi, Yamaguchi-gumi doran!! (Turmoil in the Yamaguchi-gumi!!). Take Shobo.

Mizoguchi 2011b: Mizoguchi Atsushi, Yakuza hokai: shinshoku sareru rokudaime Yamaguchi-gumi (Yakuza Collapse: The Erosion of the Yamaguchi-gumi). Kodansha.

Mizoguchi 2011c: Mizoguchi Atsushi, Boryokudan (The Yakuza). Shincho Shinsha.

Mizoguchi 2011d: Mizoguchi Atsushi, Yamaguchi-gumi doran!! (Turmoil in the Yamaguchi-gumi!!). Revised Edition. Take Shobo.

MOJ 1989: Ministry of Justice (MOJ), Heisei gannen hanzai hakusho (White Paper on Crime 1989).

MOJ 2011: MOJ, Heisei 23-nen hanzai hakusho (White Paper on Crime 2011).

Mook 2005: Mook Y Henshubu, Yamaguchi-gumi Tokyo senso (The Yamaguchi-gumi’s Tokyo War). Yosuisha.

MPD 2011: Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), Tokyo-to boryokudan haijo jorei (Tokyo Yakuza-Exclusion Ordinance).

Nakano 2010: Nakano Jiro, Ura-shakai: uwasa no shinso (The Truth about the Underworld). Saizusha.

NHK 2008: NHK yakuza mane shuzaihan (NHK Investigative Team), Yakuza mane (Yakuza Money). NHK.

NPA 2007a: National Police Agency (NPA), Heisei 19-nen kamihanki boryokudan josei (The State of Organized Crime in the First Two Quarters of 2007).

NPA 2007b: NPA, Kensetsugyo ni okeru futo-yokyu nado ni kansuru jittai chosa (Survey of Extortion in the Construction Industry).

NPA 2010a: NPA, Heisei 21-nen boryokudan josei (Yakuza Crime in 2009).

NPA 2010b: NPA , Heisei 21-nen soshiki hanzai no josei (Organized Crime in 2009).

NPA 2011a: NPA, Heisei 22-nen boryokudan josei (Yakuza Crime in 2010).

NPA 2011b: NPA, Rainichi gaikokujin hanzai no kenkyo jokyo: Heisei 22-nen kakuteichi (Crimes by Foreign Nationals in Japan).

NPA 2011c: NPA, Heisei 23-nenban keisatsu hakusho (NPA White Paper 2011).

NPA 2011d: NPA, Heisei 22-nenchu no yakubutsu/toki josei (Crimes related to Drugs and Guns during 2010).

NPA 2011e: NPA, Heisei 23-nendo gyosei taisho boryoku ni kansuru anketo (2011 Questionnaire relating to Violence against Governmental Bodies).

RFSS 2011: Shakai Anzen Kenkyu Zaidan (Research Foundation for Safe Society), Nicchu soshiki hanzai kyodo kenkyu, Nihon-gawa hokokusho: Boryokudan jukeisha ni kansuru chosa hokokusho (Survey of Incarcerated Yakuza Gang Members), June 2011.

Senba 2009: Senba Toshiro, Genshoku keikan ‘uragane’ naibu kokuhatsu (A Serving Policeman Exposes ‘Secret Money’), Kodansha.