“The near universal conviction in Japan with which the islands today are declared an ’integral part of Japan’s territory‘ is remarkable for its disingenuousness. These are islands unknown in Japan till the late 19th century (when they were identified from British naval references), not declared Japanese till 1895, not named till 1900, and that name not revealed publicly until 1950.” Gavan McCormack (2011)1

Abstract

In this recent flare-up of the island dispute after Japan “purchased” three of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Japan reiterates its position that “the Senkaku Islands are an inherent part of the territory of Japan, in light of historical facts and based upon international law.” This article evaluates Japan’s claims as expressed in the “Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands” published on the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan. These claims are: the Senkaku/Diaoyu island group was terra nullius which Japan occupied by Cabinet Decision in 1895; China did not, per China’s contention, cede the islands in the Shimonoseki Treaty; Japan was not required to renounce them as war booty by the San Francisco Peace Treaty; and accordingly Japan’s sovereignty over these islands is affirmed under said Treaty. Yet a careful dissection of Japan’s claims shows them to have dubious legal standing. Pertinent cases of adjudicated international territorial disputes are examined next to determine whether Japan’s claims have stronger support from case law. Although the International Court of Justice has shown effective control to be determinative in a number of its rulings, a close scrutiny of Japan’s effective possession/control reveals it to have little resemblance to the effective possession/control in other adjudicated cases. As international law on territorial disputes, in theory and in practice, does not provide a sound basis for its claim of sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Japan will hopefully set aside its putative legal rights and, for the sake of peace and security in the region, start working with China toward a negotiated and mutually acceptable settlement.

Keywords

Diaoyu Dao, Diaoyutai, Senkakus, territorial conflict, sovereignty,

I Introduction

A cluster of five uninhabited islets and three rocky outcroppings lies on the edge of the East China Sea’s continental shelf bordering the Okinawa Trough, extending from 25̊ 40’ to 26̊ 00’ of the North latitude and 123̊ 25’ to 123̊ 45’ of the East longitude,2 roughly equidistant from Taiwan and the Yaeyama Retto. Both Japan and China lay claim to this island group. Known as the Senkakus, or Senkaku Retto, Japan claims the islands are “clearly an inherent territory of Japan, in light of historical facts and based upon international law.”3 Rich in fishing stock and the traditional fishing grounds of Chinese fishermen, China has called the islands Diaoyutai,4 meaning “fishing platform,” or Diaoyu Dao, meaning fishing islands, since their discovery in the 14th century.

|

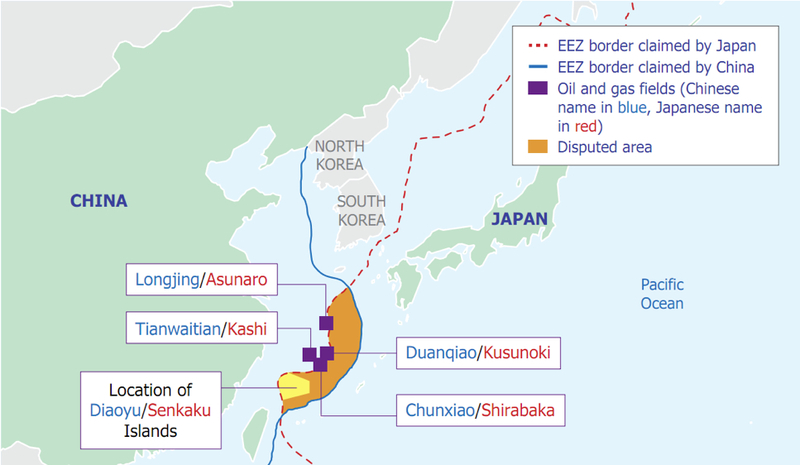

Location of Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, potential oil and gas reserves and interrelated EEZ disputed area (Source: Interfax) |

China claims a historical title to Diaoyu Dao on the bases of its discovery, its inclusion into its defense perimeter from Japanese pirates during the Ming dynasty, and its incorporation into China as part of Taiwan in the Qing dynasty. Japan, on the other hand, claims to have incorporated these islands as terra nullius in January 1895, while China maintains they were ceded to Japan at the end of the first Sino-Japanese War in April of the same year. From 1952 to 1972, the United States (US) administered these and other island groups under United Nations (UN) trusteeship according to the provisions of the San Francisco Peace Treaty (SFPT). In 1972 pursuant to the Okinawa Reversion Treaty, the US transferred administrative control of these islands back to Japan over strong protestations from China. At the urging of Japan, the US then inserted itself in the dispute by declaring any attack on the Senkakus to be equivalent to an attack on the US under Article 5 of the 1960 US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty. As China was not a signatory to the SFPT and is not bound by its terms, China continues to regard the islands as its own, citing as evidence the Cairo and Potsdam Declarations and the surrender terms Japan signed in 1945.t

The competing claims defy easy solution. The situation is complicated by the discovery of gas and oil reserves in the late 1960s, making it more difficult to disentangle the intertwining threads of irredentism, a territorial and Exclusive Economic Zone boundaries dispute, and the geopolitical considerations of the two claimants and the US.

In 1990 and again in 2006 China offered, and Japan turned down, joint resource development of the region surrounding the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. The offer was renewed as late as 2010, but Tokyo saw no reason for joint development as “China’s claims on the Senkakus lack grounds under international law and history.” 5 However, in the two countries’ maritime boundary dispute, China and Japan did reach an agreement in 2008 to jointly develop the gas deposit in the Chunxiao/Shirakaba field, although not much progress has been made since then.6 Up to mid-2012, both countries managed to skillfully tamp down occasional flare-ups of the sovereignty dispute to avoid jeopardizing Sino-Japanese political relations, the close intertwining of the two economies and the peace and security of the whole region.

|

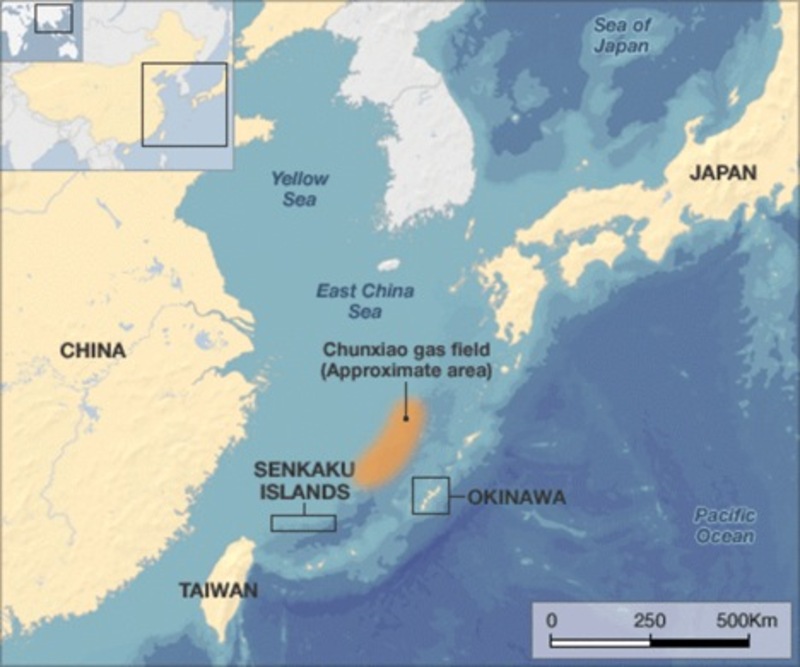

Map of Diaoyu Dao/Senkaku islands, Chunxiao gas field, Okinawa, Taiwan, China and Japan |

|

Meeting of Hu and Noda at APEC (Source: China Times) |

However, in 2012 a report began circulating that the Japanese government planned to purchase three of the Senkaku Islands, Uotsuri-jima, Kita-kojima and Minami-kojima, from a private Saitama businessman. Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko confirmed the planned purchase on July 7, attributing the move to the government’s desire to block a more disruptive attempt by Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintaro to buy and to develop the islets.7 On September 9, 2012, President Hu Jintao met with Prime Minister Noda on the sidelines of a regional Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Vladivostok to discuss the issue. Hu issued a stern warning that China was firmly opposed to the purchase plan as China also claims Diaoyu Dao as its own.8 The next day, on September 10, the Japanese Cabinet closed the purchase deal with the private owner for 2.05 billion yen.9

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs swiftly issued its own statement on the same day, stating: “Regardless of repeated strong representations of the Chinese side, the Japanese government announced on 10 September 2012 the ‘purchase’ of the Diaoyu Island and its affiliated Nan Xiaodao and Bei Xiaodao and the implementation of the so-called ’nationalization‘ of the islands. This constitutes a gross violation of China’s sovereignty over its own territory and is highly offensive to the 1.3 billion Chinese people.”10 China then took a number of steps to strengthen its own claim. On September 13, 2012, China’s Permanent Representative to the UN, Li Baodong, met with UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon to file with him a copy of the maritime chart outlining the territorial seas of China’s Diaoyu Dao and its affiliated islands. With this chart, China proposed to establish the basis on which to claim national jurisdiction over the Exclusive Economic Zone and continental shelf according to the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.11

Next, six Chinese marine surveillance ships were sent into the East China Sea on what China called a “patrol and law enforcement mission.” In the ensuing weeks, more of these non-military ships patrolled the seas around the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus, leading to Japanese and Western media reports of China’s relentless harassment of the Japanese Coast Guard,12 although these ships were doing no more than what the latter has been doing since 1972. In a new move aimed at re-affirming to the international community China’s sovereignty over Diaoyu Dao, the State Oceanic Administration and the Ministry of Civil Affairs jointly released on September 20, 2012 a list of standardized names for the geographic entities on the Diaoyu Island and 70 of its affiliated islets and their exact longitude and latitude, along with location maps.13 Finally, on September 26, 2012, the Chinese Government published a White Paper, captioned “Diaoyu Dao, an Inherent Territory of China.”14 As Global Times, published by the People’s Daily, opined, “backing off is not an option for China” now.15

Substantial segments of the international press have portrayed this flurry of acts on China’s part as unnecessary and excessive. However, China’s response can be traced to its growing knowledge of and confidence in operating in a world governed by Western rules. For example, under international law, Japan’s “purchase” is considered an effective exercise of sovereignty. Consequently, unless answered with equally forceful countermoves, Japan would have further consolidated its claim to the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. China’s policy of decisive response, in effect, keeps it in the ‘‘sovereignty game”16 and leaves open the ultimate question of who owns the islands.

Beijing was not alone in this response. Taipei reacted likewise. The Republic of China (ROC) released a position paper on September 17, 2012, captioned “Summary of historical facts concerning Japan’s secret and illegal occupation of the Diaoyutai Islands.” The paper is similar to the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) White Paper in its arguments for the sovereignty of Diaoyu Dao and identical in the historical evidence presented.17 Then on October 10, 2012, the ROC published a full-page ad in the New York Times staking out the bases for its sovereignty claim and offering an initiative for joint development of the East China Sea.18

Japan’s “purchase” reopened the still festering wound of the aggressive wars Japan waged against China in its imperial expansionism. Mass protests against Japan’s island purchase erupted in as many as 85 cities across China on the weekend after the purchase announcement.19 Television broadcast indelible images of Chinese anti-riot and paramilitary police, several layers deep, forming a phalanx around the Japanese embassy in Beijing to hold back waves of enraged protestors seemingly trying to storm the building. Stores selling Japanese goods and Japanese cars were vandalized.

|

Demonstrations across China (Source: Kyodo News) |

|

Source: Russia Today |

Meanwhile, the “purchase” prompted an armada of over 70 fishing boats to sail from Yilan (Ilan) County, Taiwan, into the territorial waters around the disputed islands to assert Taiwanese fishermen’s rights to operate in their “traditional fishing grounds.”20 Ten Taiwan Coast Guard ships escorted these fishing boats, prepared to respond in kind should the Japanese Coast Guard try to drive them off, while Taiwanese air patrols over the islands were stepped up should any contingencies arise from the protest on the high seas. Nearly 1,000 people marched through the town of Toucheng in northeastern Yilan (Ilan) County, carrying banners and flags, and chanting slogans in support of the fishing boats from the area. 21

In anticipation of another flare-up of the dispute after Japan confirmed its intention to “buy” the islands on July 7, a reporter questioned the US stance in a State Department press conference on August 28, 2012. Spokesperson Victoria Nuland re-affirmed that the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus fall under the scope of Article 5 of the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty; she also reiterated that the US takes no position on the sovereignty issue. As to the competing claims advanced by China and Japan, she stated, “[o]ur position on that’s been consistent, too. We want to see it negotiated.” 22

Japan tried to split the uncoordinated but united front presented by Taipei and Beijing. Foreign Minister Gemba Koichiro called for a restart to the current round of fishery talks with Taipei which has been suspended since February 2009 due to differences over the island sovereignty issue.23 The talks were initiated in 1996 after Japan enacted a Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf, and Japanese Coast Guard ships started to harass and impound Taiwanese fishing boats, jeopardizing the men and threatening their livelihood. But 16 rounds of negotiations have failed to produce any results.

As in China and Taiwan, the domestic political climate in Japan has precluded any compromises on this issue since the purchase of the three Senkaku islands. On September 26, 2012, Prime Minister Noda delivered a speech at the UN General Assembly in an effort to rally the international community to Japan’s side in various territorial disputes with its neighbors. At a press conference after the speech Noda specifically denied a dispute exists about the Senkakus and asserted that the island group is “an inherent part of our territory in light of history and also under international law.” He continued, “[t]herefore, there cannot be any compromise that represents a retreat from this position.”24

|

Noda speaking at UN (Source: Kyodo News) |

Japan’s position that “there is no dispute” regarding the Senkakus may be one of those denials in line with its other denials of war responsibility, the Rape of Nanking, the comfort women and so on. If so, the contention does not require a serious effort at rebuttal.

Alternatively, Japan may mean that the basis of its claim is so solid as to be beyond dispute. China’s evidence to the title has been amply and capably documented by scholars.25 This paper proposes to assess Japan’s claim as presented in the “Basic View of the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands” (Basic View) on the Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) website. Under close scrutiny, is Japan’s claim so legally unassailable as to admit of no other result than a ruling in its favor should the case be brought before the International Court of Justice?

II Japan’s Claim of Sovereignty over the Senkakus through Occupation and/or Prescription

The Basic View states:

“[f]rom 1885 on, surveys of the Senkaku Islands were thoroughly carried out by the Government of Japan through the agencies of Okinawa Prefecture and by way of other methods. Through these surveys, it was confirmed that the Senkaku Islands had been uninhabited and showed no trace of having been under the control of the Qing Dynasty of China. Based on this confirmation, the Government of Japan made a Cabinet Decision on 14 January 1895 to erect a marker on the Islands to formally incorporate the Senkaku Islands into the territory of Japan.”26

In essence the Japanese government contends that in 1895, the islands were terra nullius, i.e., land without owners, when Japan decided to occupy them. Terra nullius does not necessarily mean “undiscovered” so much as unclaimed territory, the title to which can be obtained through occupation. The following sections first examine whether the island group per Japan’s assertion was truly terra nullius, then whether Japan could have gained sovereignty over the Senkakus through either occupation or prescription, two legal modes of territorial acquisition.

Context of Japan’s Claim of Terra Nullius

After using gunboat diplomacy to force Korea to open its ports in 1876, and annexing the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1879, Japan turned its eyes next to the islands lying in between Okinawa and Taiwan.27 Documents declassified in the 1950s include a report dated September 22, 1885 from the Okinawa Prefectural Magistrate who, on secret orders from the Home Minister, investigated three islands, the Uotsuri-jima (Diaoyu Dao), Kuba-jima (Huangwei Yu), and Taisho-jima (Chiwei Yu). The Okinawan Magistrate noted in said report that incorporating, i.e., placing markers on, the islands would present no problem. However, he also noted that the possibility existed that these islands might be the same ones that were already recorded in the Zhongshan Mission Records, used as navigational aids by the Qing envoys to the Ryukyu Kingdom, details of which were well known to the Qing dynasty. He concluded:

”…[i]t is therefore worrisome regarding whether it would be appropriate to place national markers on these islands immediately after our investigations…” 28

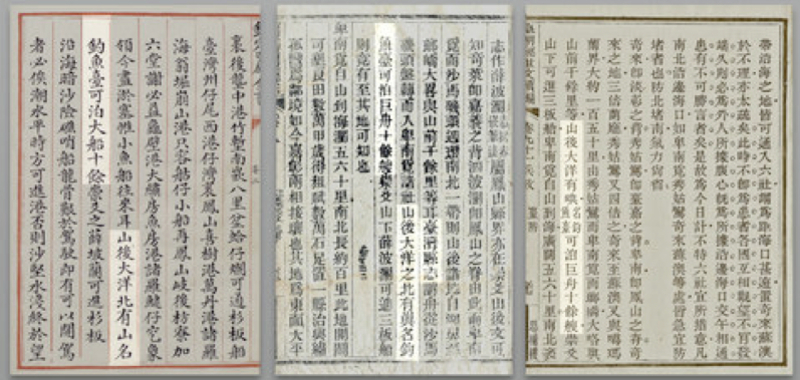

|

Record of Missions to Taiwan Waters (1722), Gazetteer of Kavalan County (1852), and Pictorial Treatise of Taiwan Proper (1872). National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. (Source: New York Times, September 19, 2012) |

Ignoring the Magistrate’s warning, the Home Minister proceeded with a petition to the Grand Council of State to install the national markers. Acknowledging that the islands might have some relation (emphasis added) to China, he nevertheless wrote:

“…[a]lthough the above mentioned islands are the same as those found in the Zhongshan Mission Records, they were only used to pinpoint direction during navigation, and there are no traces of evidence that the islands belong to China…” 29

However, when the Foreign Minister was asked for his opinion on the proposed project, he noted that Chinese newspapers were already abuzz with reports of Tokyo’s activities on the islands and of its probable intent to occupy these islands that China owned. Accordingly, he cautioned that placing national markers on the islands would only arouse China’s suspicion toward Japan and that “…it should await a more appropriate time.” He further urged the Home Minister to refrain from publishing the investigative activities on the islands in the Official Gazette or newspapers.30 A copy of the September 6, 1885, Shen Bao, carrying an account of Japanese activities on the islands has been found by Chinese scholars.31

For 10 years, Japan’s decision to tread carefully with respect to the islands held. During that time, declassified documents show two different Governors of Okinawa Prefecture requested that the central government place the islands under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture so as to regulate marine products and fishing activities around them. All these requests were denied.

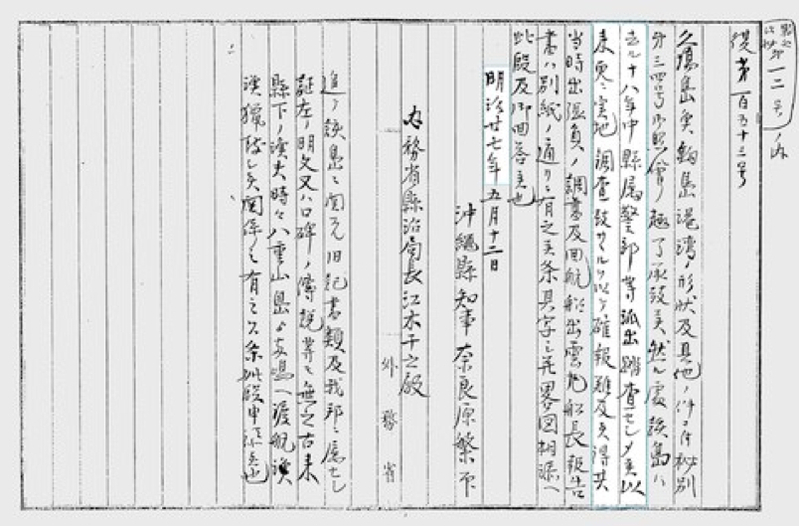

When the opportune moment came to proceed with incorporating the islands, it was not from having more surveys conducted as MOFA alleged, but rather from assurance of Japanese victory in the first Sino-Japanese War. No survey was performed following the initial investigation of 1885 as evidenced in an exchange between the Director of Prefectural Administration of the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Governor of Okinawa in the early part of 1894. In addition, the former explicitly acknowledged in said exchange the issue of placing national markers was tied to “negotiation with Qing China.” 32 Later in the same year, however, in a December 1894 document addressed to the Home Minister, the Director of Prefectural Administration inquired whether the Minister had reconsidered the matter of placing national markers as “the situation today is greatly different than the situation back then.” 33

|

Letter dated May 12, 1894, affirming that the Meiji government did not repeatedly investigate the disputed islands. Japan Diplomatic Records Office. (Source: New York Times, September 19, 2012) |

The situation had indeed changed as of late November 1894. The Japanese government was assured of victory after Japanese forces seized Port Arthur (Lüshun) in the first Sino-Japanese War. By then China was eagerly seeking a peace settlement.

Other internal documents of late 1894, such as the aforementioned Director’s summary of the so-called “investigations” of the islands and the December letter sent by the Home Minister to the Foreign Minister for endorsement of the project of installing markers, all point ineluctably to the same reason for Japan’s final decision to proceed with the project. Japan no longer feared incurring the wrath of Qing China for encroaching on its territory. No repeated surveys were done prior to the incorporation with the express purpose of ensuring the islands were terra nullius. Instead, Okinawa Prefecture conducted the first detailed land survey of some of the islands in 1901.34

Thus, on January 14, 1895, the Japanese Cabinet passed a resolution to annex the islands, a few months before the Shimonoseki Treaty which ended the first Sino-Japanese War was signed, in April 1895. Interestingly, in spite of the claim that repeated surveys were carried out, the Cabinet annexed only two of the three islands initially surveyed in 1885, Kuba-jima and Uotsuri-jima; the Taisho-jima islet was not annexed until 1921.35 As with all the aforementioned documents, the Cabinet Decision was kept secret until declassified in 1952.36 The actual placing of the physical marker did not take place until May 10, 1969, in the midst of a heated sovereignty dispute.37

Prior to 1972, the Japanese government referred to an official 1970 Ryukyu Civil Government statement, which referenced Imperial Edict No. 13 dated March 15, 1896, as further confirmation of Japan’s claim to title. This Imperial Edict presumably constituted an official proclamation of the incorporation act of January 14, 1895. However, the decree did not name the two islands.38 Neither were the islands recorded in a subsequent Okinawa official publication of districts placed under its administration pursuant to Imperial Edict No 13.

This point of ratification by Imperial Edict No. 13 was eliminated in the description of the 1972 Basic View later published on the MOFA website. However, regardless of whether MOFA references Imperial Edict No. 13 today or not, under the Meiji Constitution the emperor had the ultimate power over all legislation. A Cabinet act must be ratified by imperial edict to take effect. “Consequently, the decision of the Japanese cabinet to give permission to build a national landmark on April 1, 1896, cannot be considered a formal or valid law enacted by the state.”39

A comparison with Japan’s incorporation of other islands that it regarded as terra nullius at about the same time shows distinct differences in procedures between these cases and that of Kuba-jima and Uotsuri-jima. In these, every effort was made to follow the prevailing international standards: specifying the investigative surveys of the islands, the proclamation by Imperial Edicts and the public announcement in the Official Gazette, and expressly naming the islands and the administrative prefecture to which they belong.40

Thus the lack of diligent investigation, the postponement until the arrival of the “appropriate” moment, the irregularities in adhering to the customary practice of incorporating terra nullius, the lack of official sanction by the emperor, and the attendant secrecy before and after the incorporation all militate against the claim that Japan determined the Senkakus to be terra nullius in 1895. In fact, the present-day name of the Senkakus was bestowed on the island group by Kuroiwa Hisashi five years after its incorporation in a 1900 article he wrote for a geography journal.41 MOFA’s assertion that the Senkakus was confirmed to show “no trace of having been under the control of Qing Dynasty of China” directly contradicts the declassified documents discussed above. These documents repeatedly and specifically mentioned “Qing China” and conveyed Japan’s initial concern about arousing China’s suspicion. Such is the foundation on which Japan chooses to stake its claim to the islands.

Acquisition Through Occupation

Under international law, territories can be acquired through a mode known as occupation when certain conditions are met. The territory, to begin with, must be terra nullius. The acquisition of title over terra nullius must be consolidated through effective occupation, exhibiting both animus and corpus occupandi, that is, the intention to occupy, followed by the actual exercise of sovereign functions.42

In animus occupandi a state shows its intention to occupy through a formal announcement or some other recognizable act/symbol of sovereignty such as planting of a flag.43 An official Cabinet Decision to install a national marker for example would qualify as animus occupandi were the island truly terra nullius. But, as previously discussed, the Cabinet incorporation act cannot be considered official without formal confirmation from the emperor. Imperial Edict No. 13 and the attendant Okinawa publication cannot be counted as imperial approval and official notification when the islands were not specifically named. Further, the Cabinet Act was kept secret for years. Thus whether a secret and possibly unofficial Cabinet resolution is considered sufficient evidence of animus occupandi is open to question. That the Japanese government acted in bad faith seems clear. Certainly, the secretive implementation of animus occupandi deprived China of constructive knowledge and a chance to lodge a formal protest against Japan’s action.

MOFA cites in its English-language Questions and Answers section on the Senkaku Islands webpage (Q & A) a number of instances that allegedly fulfill the requirement of corpus occupandi. The “discovery” of Uotsuri-jima (Diaoyu Dao), the largest of the islands, was accredited to Koga Tatsushiro from Fukuoka in 1884. When Koga applied to Okinawa Prefecture for a lease of the islands in 1894, the prefecture turned him down, stating it did not know whether the islands were Japanese territory or not. Koga persisted. He filed another application on June 10, 1895, six days after Japan officially occupied Taiwan (Formosa), which China ceded to Japan in the Shimonoseki Treaty after the first Sino-Japanese War. Koga’s timing should be noted. As pointed out in a biography, he attributed Japan’s possession of the islands to “the gallant military victory of our Imperial forces.” 44 The Ministry of Home Affairs finally approved this application in September of 1896.

Koga was given a 30-year lease without rent to four islands, Uotsuri-jima (Diaoyu Dao), Kuba-jima (Huangwei Yu), Minami-Kojima (Nanxiaodao Dao) and Kita-Kojima (Beixiao Dao). He spent large sums of his own money to develop the islands, and brought over workers from Okinawa to gather albatross feathers and to operate a bonito processing plant on Uotsuri-jima. At its peak, there were more than 100 people working on the islands. In 1926, when the lease expired, the Japanese government sold the four islands to the Koga family for a nominal sum and they became privately owned land. No official record, however, could be found to show that Koga paid property tax on the islands; nor was there a building registration for the bonito processing plant.45 With growing China-Japan tensions, Koga closed his business in the islands in the 1930s. In 1978, the islands were sold for a nominal price of 30 yen per 2.3 square meters to the Kurihara family.46

The Q & A maintains, “[t]he fact that the Meiji Government gave approval concerning the use of the Senkaku Islands to an individual, who in turn was able to openly run these businesses mentioned above based on the approval, demonstrates Japan’s valid control over the Islands.” 47 This example of Japan’s “valid control” provides the proper context to view its recent purchase of three Senkaku islands from a private owner: the purchase could later be adduced as another display of Japan’s “valid control.” The purchase, however, is a provocative act under international law in the sense that it requires a vigorous response from a China who does not administer these islands if it wishes to maintain its claim. Otherwise China would appear to or be presumed to have acquiesced to Japan’s occupation. Thus China’s recent series of actions, i.e., diplomatic protest, filing China’s maritime chart with the UN and so on, probably constitute no more than is required to keep alive its claim to title.

Acquisition through Prescription

As can be seen from the preceding section, Japan may not have satisfied the initial requirement of terra nullius; nor has it fully met the condition of animus occupandi. Recognizing the claim of title by occupation may not stand however, some Japanese and American scholars and commentators have contended that Japan could have acquired sovereignty under the modality of prescription.

Prescription comes into play when the territory is of unknown, uncertain or questionable ownership. It consists of two distinct requirements. First, the state must show “immemorial possession” of the territory in question to justify the present status quo, i.e., its current occupation or possession.48 Japan certainly fails this bar. Even according to Koga’s claim, the “discovery” of the islands occurred in 1884 while Chinese records of the islands date back to the Ming dynasty in the 14th century. The difference in alleged “possession” time from thereon is great between Japan and China.

The second requirement for prescription shown to be the more important in arbitral and judicial decisions, refers to a process of acquisition akin to adverse possession in civil property law. It involves, on the one hand, a period of continuous, peaceful and public display of sovereignty by the adverse possessor state to legitimize a doubtful title. It demands, on the other hand, acquiescence by other interested or affected states, either in the form of a failure to protest or actual recognition of the change of title. 49

It is unclear whether the Japanese government adopts this line of reasoning but elements of the argument appear in MOFA’s Q & A webpage. For example, it maintains that “…the contents of these documents (Chinese historical documents) are completely insufficient as evidence to support China’s assertion (of sovereignty) when those original documents are examined,” 50 implying that China’s claim to ownership of the Senkakus’ is uncertain. MOFA’s Basic View further states, “[t]he Government of China and the Taiwanese authorities only began making their own assertions on territorial sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands in the 1970s, when the islands attracted attention after a United Nations agency conducted an academic survey in the autumn of 1968, which indicated the possibility of the existence of petroleum resources in the East China Sea.” 51 This last purportedly shows China’s prior acquiescence, simultaneously raising questions of motivation for current non-acquiescence.

Conceptually, occupation and prescription, the two modes of acquiring territory, may be distinct but operationally the two overlap and can be applied to the same set of data.52 As modern-day territorial disputes are adjudicated on the merits of competing claims with sovereignty going to the better right to title, Heflin, among others, concludes Japan has the more colorable (plausible) claim.53

That Japan’s claim is more colorable is debatable. In civil law, the legal doctrine of adverse possession is highly problematic for a system based presumably on equity and justice. Defined as the acquisition of a legitimate title to land actually owned by another, it requires certain stringent conditions to be met and for the length of time as determined by the statute of limitations.54 Otherwise few rationales could justify a wrongful possession ripening into a legitimate one and a legal transfer of land from owners to non-owners without consent of the former. Therefore, to lessen the chance of a possible miscarriage of justice, the possession must be actual, hostile, open and notorious, exclusive, and continuous for the period of the statute of limitations.55 The requirement of “open and notorious,” for example, calls for the possession to be carried out visibly to the owner and others, thus serving notice of the adverse possessor’s intent while “actual” possession provides the true owner with legal recourse for trespassing within a period of time. Still, the principle’s mere existence may work as an incentive to theft, requiring constant monitoring by the true land owner and for this reason may be unfair.56

As for the principle of prescription, though widely recognized by scholars and included in textbooks as one of the modes of territorial acquisition, it too is of “very doubtful juridical status.” 57 Nonetheless, Japan’s possible acquisition of the Senkakus through prescription will be evaluated next.

The first question to consider is whether Japan has satisfied the condition of a long, uninterrupted and peaceful display of sovereignty. Only the period between 1895 and 1945 can be counted as one of peaceful display of Japan’s sovereignty unchallenged by China. A plausible explanation for China’s silence will be considered in the later section on treaties relevant to the dispute. Regardless, the period is probably too short to validate an adverse claim. Japan resumed direct control of the islands again from 1972 to the present, but during this period it has been repeatedly confronted by China whenever attempts were made to exercise acts of sovereignty. Despite considerable efforts, Japan could not persuade the US in 1972 to turn over sovereignty to Japan. For reasons of its reasons, the US government’s position was and continues to be that only administrative control of the islands was transferred under the Okinawa Reversion Treaty.

As to the condition of acquiescence, Japan claims that by failing to protest at critical moments, China showed acquiescence. However, MacGibbon points out that “[r]ights which have been acquired in clear conformity with existing law have no need of the doctrine of acquiescence to confirm their validity.”58 Only where rights are suspect does the doctrine come into play. Accordingly, “acquiescence should be interpreted restrictively.”59 It should be applied to cases where the acquiescing state has constructive knowledge of the prescriptive state’s claim. Given the secrecy surrounding Japan’s incorporation process, China was denied that constructive knowledge.

MacGibbon discusses another situation where acquiescence cannot be assumed, one in which “the question (of the claim) has been left open by the disputing parties.”60 China’s tacit agreement with Japan to “shelve” the issue of the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus falls into such a category. The first recorded instance of this agreement occurred in 1972 during normalization talks between the two countries. Pressed by Tanaka Kakuei, Prime Minister of Japan, on the island issue, Zhou Enlai, Premier of the PRC, said he did not wish to talk about the issue at the time because it posed an obstacle to normalization of relations. According to Chinese records, Tanaka agreed, saying he had to raise the issue because the Japanese public expected it.61 Then in 1978, PRC Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping again talked about shelving the issue, commenting that “[o]ur generation is not wise enough to find a common language on this question. Our next generation will certainly be wiser. They will find a solution acceptable for all.”62

In an interview published in October 2012, Professor Yabuki Susumu charged MOFA with excising the minutes of the Zhou-Tanaka exchange from the MOFA website along with Tanaka’s solemn apology for Japanese aggression in the Asia-Pacific War.63 But MOFA denies that such an agreement ever existed: ”…it is not true that there was an agreement with the Chinese side about ‘shelving’ or ‘maintaining the status quo’ regarding the Senkaku Islands.” As of December 2012, a translation of the conversations between Zhou and Tanaka and between Deng and Prime Minister Fukuda Takeo was posted on its Q & A webpage presumably to substantiate MOFA’s point.64 Assuming the MOFA posting to be a full disclosure, note in the first conversation that it was Tanaka who brought up the subject of Senkakus with Zhou. Were there no controversial issue and no possible dispute, why would Prime Minister Tanaka raise the issue at all? And did not the silence (lack of response) from Fukuda in the 1978 conversation indicate assent or acquiescence? And would Fukuda not have protested immediately if Deng was not summarizing the situation correctly per Japan’s reasoning? The tacit agreement to shelve the sovereignty question is surely not a figment of China’s imagination. The Deng statement is something scholars have written about approvingly and has been extensively covered in the global media.

Prior to September 2012, both China and Japan had engaged in active dispute management.65 For instance, both governments attempted to limit activists’ access to the islands. Japan had not only enacted measures to restrict access but had also not developed or made use of the islands to any great extent. Japan had not, for example, erected any military installation on the islands, a move that would consolidate its control but would surely provoke Chinese countermeasures.66 China, too, had done its part: it “refused to support private sector [the Baodiao or “Defend Diaoyutai” movement] activities.” Nor did China condone “fishermen who traveled to Diaoyu Island waters to catch fish,” and it also “refrained from conducting maritime surveillance.”67 Although the American media and politicians repeatedly blamed Beijing for mobilizing Chinese opinion against Japan on the island dispute, in actuality, for many years, China had officially or unofficially tried to minimize media coverage of the conflict. Further, as Fravel points out, “the Chinese government ha[d] restricted the number, scope and duration of protests against Japan over this issue.”68

Thus Japan and China had both abided by this informal agreement until recently, leading the Japan Times to observe that “[p]revious governments under the LDP, which was ousted from power by the DPJ in the 2009 general election, had respected (this) tacit agreement Tokyo allegedly reached with Beijing in the 1970s.” 69 One consequence of Japan’s current repudiation of the tacit agreement to shelve the Senkaku/Diaoyu Dao issue has been to alert China of the need to match Japan’s exercise of state functions, i.e., to conduct regular patrols of the disputed areas to sustain China’s claim. Unfortunately, the regular patrolling now is seen by much of the American media and public as evidence of the rise of a more “assertive” or “belligerent” China.

Although Japan does not officially claim the Senkakus under prescription, a closer look into the practical requirements of this mode may provide an explanation for Japan’s curious statement that there is no territorial dispute. According to Sharma, the prescribing state which is in control “should not…by its own conduct admit the rival claim of sovereignty of any other state; otherwise it will be precluded or barred from claiming the prescriptive title to sovereignty.”70 Admitting China’s competing claim may be an obstacle to acquisition by prescription and may, in addition to Japan’s unshakable confidence in the righteousness of its own claim based on international law, serve as an impetus to Japan’s denial.

To sum up, Japan’s claim to sovereignty of the Senkakus is less firmly grounded in international law than it maintains. Nor are international courts necessarily the appropriate venue for resolving a territorial dispute as entangled as that of the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. International law demands displays of sovereignty to consolidate a title; further it penalizes the state that appears to acquiesce. Japan’s rationalization of its claim on the basis of international law not only provides it with a powerful rhetoric for its assertions, but also with an incentive to make assertions of sovereignty. This could provoke a response in kind from China in a cycle of escalation, leading possibly to armed confrontations in the region.

Aware of this danger, China had in the past made offers of joint development of the area when tensions subsided after a flare-up of the dispute or in a more relaxed atmosphere in which it would not be seen as conceding. Clearly then, China’s position is not all about making a unilateral claim to the oil and gas reserves in the seas surrounding Diaoyu Dao.71 It is unfortunate that Japan repeatedly refused such offers for the PRC has an enviable record of settling most of China’s fractious border disputes derived from a legacy of Western colonialism. China has even accepted unfavorable agreements for the sake of peaceful neighborly relations.72 Japan probably thinks it has such firm backing from international law that it can ignore China’s proactive gestures. But certain precepts of international law seem to have encouraged Japan’s bizarre insistence that there is no territorial dispute regarding the Senkakus and its denial of the existence of a tacit agreement with China to shelve the issue.

III Treaties that Japan Claims Govern the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus Dispute

As evidence to support its claim of sovereignty over the Senkakus, Japan invokes the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty (SFPT) which stipulates disposition of its acquired and annexed territories. Japan rejects the Chinese assertion that the Senkakus were ceded to it in the 1895 Shimonoseki Treaty. Finally it points to the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Treaty for the return of the Senkakus into the sovereign fold of territories that had been temporarily placed under US administration. Together these treaties presumably substantiate Japanese claim to title. Yet none of these specifically addresses the issue. All demand a “treaty interpretation” giving rise to the disputants’ claims and counter-claims. Treaties that may be relevant to the dispute will be examined next.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki

In August 1894 the first Sino-Japanese War broke out over control of Korea. A militarily modernizing Japan, seeking to detach Korea from Chinese suzerainty as a tributary state, embarked on its first war of expansion. After defeating China’s naval fleet, Japan invaded China in late October of the same year. By November China sued for peace after Japan won a decisive victory at Port Arthur. The war was formally concluded with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed on April 17, 1895. According to Japan:

“. . . the Senkaku Islands were neither part of Taiwan nor part of the Pescadores Islands which were ceded to Japan from the Qing Dynasty of China in accordance with Article 2 of the Treaty of Shimonoseki which came into effect in May of 1895…” 73

The pertinent portion of Article 2 of the Shimonoseki Treaty states:

China cedes to Japan in perpetuity and full sovereignty the following territories, together with all fortifications, arsenals, and public property thereon:-

(b) The island of Formosa, together with all islands appertaining or belonging to the said island of Formosa.74

As there is no specific mention of Diaoyu Dao in this Article, Japan asserts that the island group was not ceded through this Treaty. China maintains otherwise.

The controversy centers on the interpretation of the clause “all islands appertaining or belonging to the said island of Formosa (Taiwan)” as to whether it includes Diaoyu Dao. Both Beijing and Taipei point to the same historical documents as proof that the island group had been under the jurisdiction of Taiwan during the Qing dynasty, with Taiwan itself incorporated into Chinese territory in 1683. For instance, among others, the same document known as “Annals” in Beijing’s reference75 and a “gazetteer” in Taipei’s76 is cited to support China’s contention.

Local gazetteers (Annals) were an important source of evidence as to what constituted Chinese territories even before the emergence of the island dispute. For example, when Japan invaded Taiwan in the 1874 Taiwan Expedition, purportedly in retaliation for aborigines killing shipwrecked Ryukyuan fishermen, China used local gazetteers to try to convince Japan that Taiwan was not terra nullius per Japan’s assertion. Japan, China declared, had in fact invaded Chinese territory.77

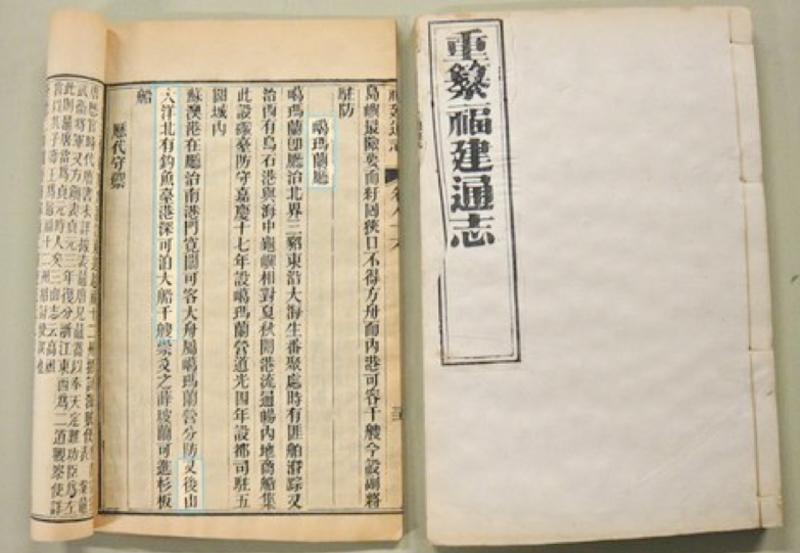

China cites the Annals/gazetteer type of historical documents to support the contention that “[f]rom Qing China’s perspective, the disputed islands became Japanese territory as a spoil of war and was legalized through the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki.”78 These documents lend credence to China’s claim that in Chinese usage and common understanding, at the time and also now, the term “appertaining islands” includes Diaoyu Dao since the islands were recorded under Kavalan, Taiwan, in the Revised Gazetteer of Fujian Province of 1871 before the start of the first Sino-Japanese War. (See photo below.) Thus China is invoking the cardinal rule per the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) of interpreting “in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning (emphasis added) to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context (emphasis added) and in the light of its object and purpose”79 to justify its position, while Japan claims the non-inclusion of the specific name of Diaoyu Dao as its rationale.

|

Diaoyu Island is recorded under Kavalan, Taiwan, in Revised Gazetteer of Fujian Province (ROC) or Gamalan, Taiwan in the Recompiled General Annals of Fujian (PRC) in 1871. (Source: New York Times, September 19, 2012) |

From China’s interpretation of this treaty, i.e., that it did cover Diaoyu Dao, may flow a plausible explanation for its silence from 1895-1945. These two factors, treaty interpretation and subsequent silence, cohere to form a plausible explanatory scenario of China’s so-called acquiescence. China did not know that Japan had secretly incorporated the islands; it believed that it had ceded the islands after the first Sino-Japanese War and was observing the maxim of pacta sunt servanda, i.e., fulfilling its treaty obligations in good faith without protest.

The fact remains, however, that although Diaoyu Dao was not expressly mentioned in the Shimonoseki Treaty, the Pescadores Group was, with specific geographic boundaries in Article II of the same treaty: “The Pescadores Group, that is to say, all islands lying between the 119th and 120th degrees of longitude east of Greenwich and the 23rd and 24th degrees of north latitude.”80 To be sure, Diaoyu Dao cannot be compared with the Pescadores in terms of size or strategic importance to China, and might not have merited a specific mention in 1895. It was, at the time in question, an insignificant group of islands, uninhabited and of limited economic value other than providing rich fishing grounds for the locals’ livelihood.

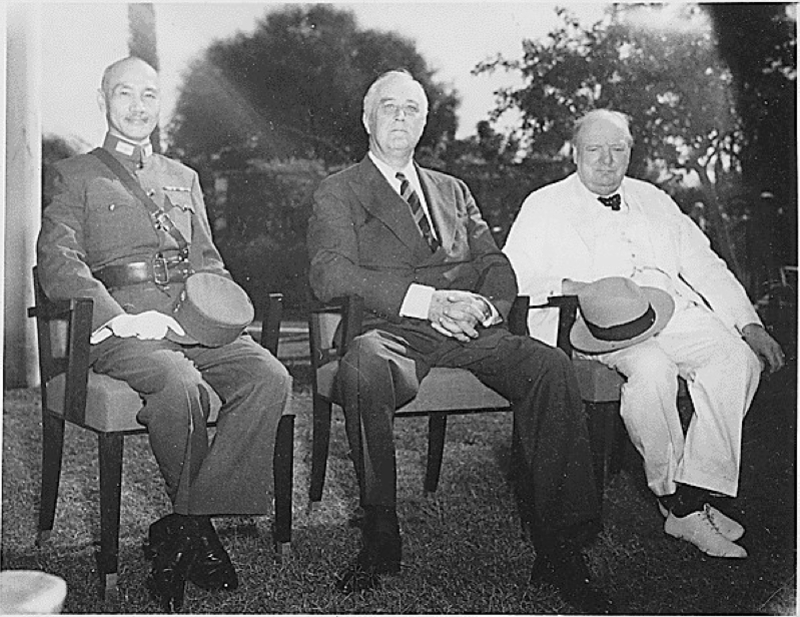

China also maintains that when the Shimonoseki Treaty is considered and interpreted as an integrated whole with other relevant written legal agreements, then Diaoyu Dao should have been returned to China after World War II. The Cairo Declaration states that “…all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China.”81 Note that this provision is not particularly careful in outlining specifics; Formosa was written with the controversial “appertaining islands” while the geographical co-ordinates of the Pescadores were not given. Nonetheless the intention to revert the territorial concessions of the Shimonoseki Treaty to China is clear.

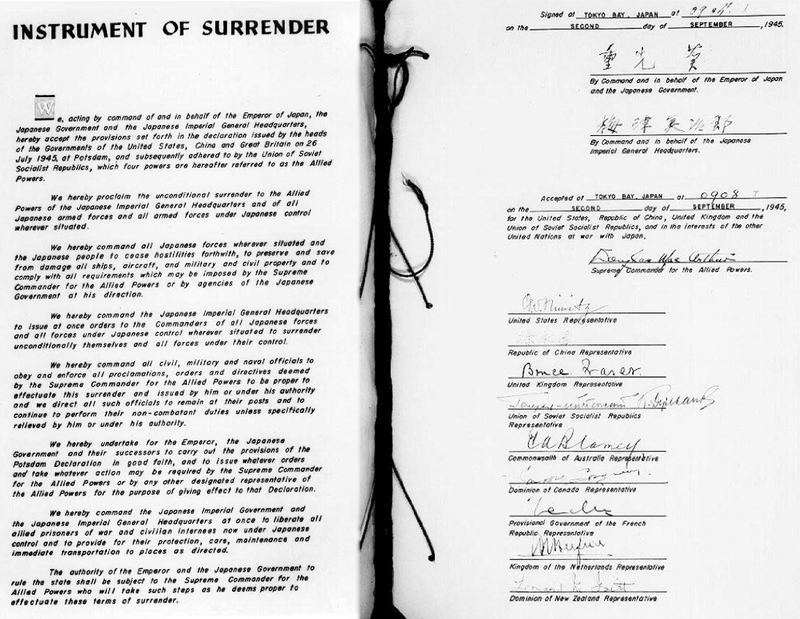

The instrument of surrender that Japan signed in 1945 pledges to accept the provisions of the Potsdam Proclamation. This latter not only affirms the terms of the Cairo Declaration but is more specific as to the territorial delimitation of Japan to “the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine.”82 These “minor islands” were listed in the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers’ Memorandum for the Imperial Japanese Government, No. 677 (SCAPIN-677), dated January 29, 1946. Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus was not on this list of Japanese “minor islands.” However, in anticipation of a peace treaty, SCAPIN-677 did insert a caveat stating that “[n]othing in this directive shall be construed as an indication of Allied policy relating to the ultimate determination of the minor islands referred to in Article 8 of the Potsdam Declaration.”83

|

Chiang, Roosevelt, and Churchill at the Cairo Conference, Egypt, November 1943 (Source: http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=68) |

The San Francisco Peace Treaty: Article II

Japan relies on the San Francisco Peace Treaty (SFPT) as the final arbiter on postwar settlement of its claims and disposition of its acquired and annexed territories. This treaty, it holds, bolsters Japanese claims since:

“…the Senkaku Islands are not included in the territory which Japan renounced under Article II of the San Francisco Peace Treaty which came into effect in April 1952 and legally demarcated Japan’s territory after World War II.”84

The Senkaku islands are indeed not mentioned in Article II (b) which stipulates:

“Japan renounces all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores.”85

The intent in the early drafts of the San Francisco Peace Treaty might have been to define the postwar territory of Japan and to codify principles expressed in such prewar agreements as the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation. Article II would then have specified the reversion of territories to China which were ceded to Japan through the Shimonoseki Treaty. But the Article as stated omitted the controversial phrase “together with all islands appertaining or belonging to the said island of Formosa (Taiwan).” The careful geographic delineation of the Pescadores group was also missing. Finally, the recipient of those renounced territories, China, was not named and left intentionally unspecified. Why?

In 1949, China’s civil war ended with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) establishing firm control over mainland China and the Republic of China (ROC) retreating to Taiwan and its outlying islands. Nations were divided in their recognition of the legitimate representative government of China. The United Kingdom (UK) established diplomatic relations with the PRC in January of 1950 while the US and many of its allies stood by the ROC at that time.

|

Japanese Surrender Document (Source: http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/japanese_surrender_document/) |

|

Oil painting by Chen Jian. Surrender Ceremony in Nanjing. Japanese representatives offer the surrender document and their swords to the Chinese representative, September 9, 1949 (Source: http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2005-05-28/19126776619.shtml) |

Also by 1949, the US with UK backing began to assume control and eventually came to monopolize the preparation of the peace treaty. When Wellington Koo, the ROC’s ambassador to Washington, learned of the SFPT terms, he strenuously objected to the fact that no reparations were demanded of Japan. More importantly, he insisted that Taiwan should be ceded back to China, as the ROC at the time was recognized by the UN as representing all of China, rather than leaving its sovereignty status indeterminate.86 John Foster Dulles, who oversaw the drafting and the passage of the SFPT, rejected Koo’s demand. Dulles reasoned that with the Korean War in progress from June 1950 and the dispatch of the US Seventh Fleet to Taiwan, the use of the fleet in the area might then “constitute an interference in China’s internal problems.”87 Koo indicated that the ROC could not accept the terms, but would not publicly remonstrate against the treaty. Neither the ROC nor the PRC was represented at the conference, and neither was among the signatories of the SFPT.

When a treaty itself gives no indication as to the disposition of a contested territory, its drafts may be used as a supplemental means for interpretation per the Vienna Convention of the Law of Treaties (VCLT).88 In the first available draft of the SFPT dated March 19, 1947, the territorial limits of Japan were defined as “those existing on January 1, 1894, subject to the modifications set forth in Articles 2, 3…”89 Had the phrasing survived the re-drafting process, the implication for the disposition of Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus would be clear since the Cabinet Decision to incorporate took place on January 14, 1895. In the same draft, however, a clause reversing the Shimonoseki Treaty provided a list of adjacent minor islands to Taiwan and the Pescadores without naming Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus.90 Accordingly, some scholars conclude on examination of this draft that the US had not intended to return Diaoyu Dao to China.

However, if the aforementioned SCAPIN-677 is taken into account, this view is not necessarily borne out because Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus was not on the list of islands SCAP considered to be under Japanese sovereignty. Alternatively, the ambiguity and conflict in the two provisions of the same draft may be attributed to the drafters’ lack of knowledge about the geography of the area and the insignificance of the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus at the time, as well as ignorance of the Chinese historical claim and Japan’s secret incorporation of the Senkakus. Thus nothing conclusive can be gathered from this draft. In later drafts Japanese territory was delimited to the four main islands and other unspecified minor islands as expressed in the Potsdam Proclamation, but again, none of those provisions survived with the changing geopolitical climate and the onset of the Cold War.

The San Francisco Peace Treaty: Article III

Japan also refers to Article III of the San Francisco Peace Treaty which stipulates:

“Japan will concur in any proposal of the United States to the United Nations to place under its trusteeship system, with the United States as the sole administering authority, Nansei Shoto south of 29 deg. north latitude (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands), Nanpo Shoto south of Sofu Gan (including the Bonin Islands, Rosario Island and the Volcano Islands) and Parece Vela and Marcus Island. Pending the making of such a proposal and affirmative action thereon, the United States will have the right to exercise all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction over the territory and inhabitants of these islands, including their territorial waters.”91

Consequently Japan concludes:

“…[t]he Senkaku Islands were placed under the administration of the United States of America as part of the Nansei Shoto Islands, in accordance with Article III of the said treaty…”92

Like Article II, Article III is silent on the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. Ambiguity also surrounds the interpretation of the phrase “Nansei Shoto (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands).” Taira Koji observes that two possible meanings can be attached to the usage of the above-mentioned phrase. Geographically, and historically, “Nansei Shoto” refers to island groups such as the Tokara, the Amami, the Okinawa and the Yaeyama, but does not include the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus or the Daito Islands. Administratively, the islands were attached to Okinawa Prefecture shortly after incorporation. Therefore “[t]he absence of mention of the Senkaku Islands in the Treaty definition of Nansei Shoto is a geographically correct usage of the term.” 93 Thus the application of the “ordinary meaning” to this phrase per Article 31 (1) of the VCLT arguably implies Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus is not part of the territory to be placed under US administration.

However, Article 31 (3a) of the VCLT also permits “any subsequent agreement between the parties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or the application of its provisions” to be taken into account. The subsequent agreement in this case is the proclamation of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyus (USCAR) No. 27 issued on December 25, 1953. It defines the geographic boundaries of the area under US administration per Article III of the SFPT, with Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus located within the defined area of US control.94 Thus USCAR 27 could be said to have clarified the phrase of “Nansei Shoto (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands),” indicating it should be interpreted in an administrative sense. However, being a declaration drawn subsequent to the treaty, it does not have the same weight as a treaty provision, especially when the reason or motivation for the inclusion of Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus by the USCAR 27 is challenged. It follows that the “administrative” interpretation of Article 3 is by no means definitive.

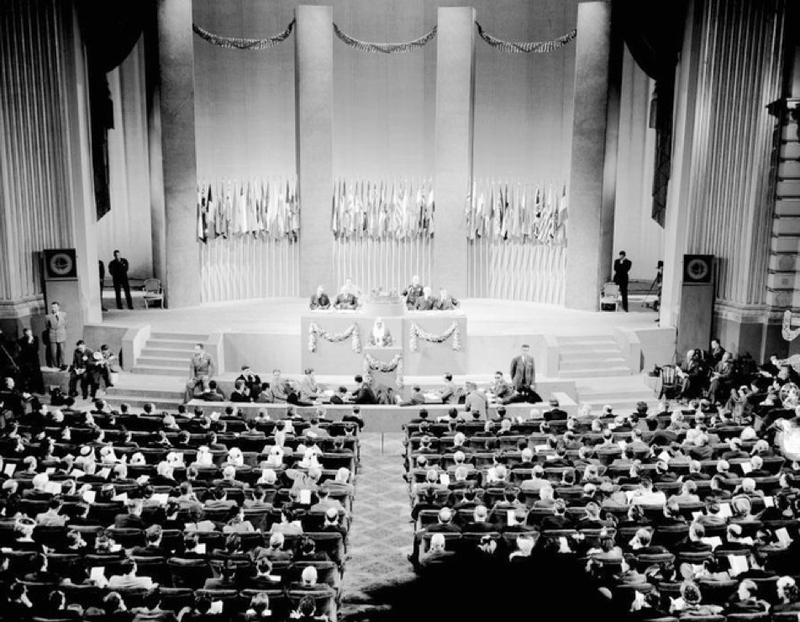

While the terms of the treaty were generous to Japan, the SFPT was drafted so as to reflect the geopolitical and strategic interests of the US with little attention devoted to the problem of settling territorial disputes of rival claimants in Asia. Therefore a review of the treaty shows that none of its provisions includes an explicit reference to Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. Despite Japan’s statement that “[t]he facts outlined herein (Articles II & III in SFPT) clearly indicate the status of the Senkaku Islands being part of the territory of Japan,” these clauses have no implication for the sovereignty of the islands. Apart from considerations of whether the treaty was just,95 and whether it “served as a sweetener for the less equitable [US-Japan] security treaty” that followed,96 the SFPT, in essence, sowed the seeds of Japan’s postwar territorial disputes, roiling relations with its neighbors and jeopardizing the peace and security of the region.

|

The San Francisco Peace Treaty, 1951, signed by 48 nations. China was not one of the signatories. (Source: http://cdn.dipity.com/uploads/events/7d7968b16dd64715e1d08893f2fd90f6_1M.png) |

Finally, Japan’s treaty interpretation is clearly inconsistent and self-serving. First, it asserts that as an administrative territory of Nansei Shoto Islands, the Senkakus should be understood to be included in Article III of the SFPT while denying that Diaoyu Dao, administered by Taiwan, should be recognized as a territory ceded in the phrase “islands appertaining to Formosa” of the Shimonoseki Treaty. Second, it argues for opposing conclusions based on the same fact, i.e., non-inclusion of Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus in treaty language. Without being mentioned, Diaoyu Dao is not ceded to Japan per the Shimonoseki Treaty; at the same time without express inclusion, the Senkakus’ sovereignty is validated through the SFPT.

Protest from Beijing and Taipei

In the Basic View, Japan goes on to say:

“The fact that China expressed no objection to the status of the Islands being under the administration of the United States under Article III of the San Francisco Peace Treaty clearly indicates that China did not consider the Senkaku Islands as part of Taiwan.”97

The statement is flawed, first, because neither the PRC nor the ROC was a signatory to the Treaty, and second, the SFPT was silent on the status of Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. On both counts it is unreasonable to expect either Beijing or Taipei to raise a specific objection as to the island group’s disposal.

In fact Zhou Enlai, Premier of the PRC, objected to the whole treaty. In a statement published on August 16, 1951, he declared that the SFPT violated the spirit and letter of the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942, which states, “[e]ach Government pledges itself to cooperate with the Governments signatory hereto and not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.”98 “China,” Zhou stated, “reserves [the] right to demand reparations from Japan and would refuse to recognize the treaty.”99 But the PRC did not have diplomatic relations with either the US or Japan at the time, and it was locked in combat with the US in the Korean War. Its protest went unheeded.

|

The United Nations Declaration, January 1, 1942, stating “Each Government pledges itself to cooperate with the Governments signatory hereto and not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.” (Source: http://www.un.org/en/aboutun/charter/history/declaration.shtml) |

As noted in the aforementioned Koo-Dulles exchange, the ROC kept silent about its rejection of the SFPT, being dependent at the time on the US for diplomatic recognition and economic and military assistance. In addition, while it may have recognized the SFPT in the 1952 Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty, Taipei did not consider the SFPT to have any bearing on the question of sovereignty of either Diaoyu Dao or any of the islands placed under US administration pursuant to Article III of the SFPT. When it realized too late this mistake in November 1953, Taipei raised diplomatic objections to the American decision to “return” the Amami islands to Japan.100 However, over Taipei’s objections, the US returned these islands as a “Christmas present” in December 1953.

The Okinawa Reversion Treaty

Japan goes on to state in the Basic View that:

“…[the Senkaku Islands] were included in the areas whose administrative rights were reverted to Japan in accordance with the Agreement between Japan and the United States of America Concerning the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands, which came into force in May 1972.”101

Again, the Senkakus is not explicitly named in the Okinawa Reversion Treaty. Instead the treaty refers to the “Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands,”102 although at the signing of this treaty a number of US officials affirmed that the Senkakus were included in the territories reverted.

Under the UN international trusteeship system, the Senkakus and other island groups of Article III, SFPT, fall into the UN Article 77 (1b) category of territories detached from Japan after World War II. The status of such territories is not altered under trusteeship per UN Article 80(1).103 This means that whatever legal status the Senkakus has at the beginning of the trusteeship, it retains the same status upon reversion.

Indeed, this is what Secretary of State William Rogers affirmed at the Okinawa Reversion Treaty Hearing in Congress, while Acting Assistant Legal Adviser Robert Starr explained in greater detail:

“The United States believes that a return of administrative rights over those islands to Japan, from which the rights were received, can in no way prejudice any underlying claims. The United States cannot add to the legal rights Japan possessed before it transferred administration of the islands to us, nor can the United States, by giving back what it received, diminish the rights of other claimants. The United States has made no claim to the Senkaku Islands and considers that any conflicting claims to the islands are a matter for resolution by the parties concerned.”104

Contrary to what Japan desires, the US then and since has maintained neutrality with regard to the sovereignty issue and declares that it transferred only administrative rights in the Okinawa Reversion Treaty. However, the US State Department simultaneously assures Japan that the Senkaku islands are protected by Article 5 of the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty of 1960, which obliges the US to come to its aid if territories under Japanese administration are attacked.105

The US arrived at this convoluted position following backroom pressure from both China and Japan. On the surface the US remains neutral. Nevertheless, the US position guarantees that “Japan enjoys – albeit circumscribed – effective control over the islands, which China could only overturn with the use of force.”106 This obvious tilt to Japan did not pass unnoticed. State Department documents show that on April 12, 1971, Chow Shu-kai, the then-departing ROC ambassador, raised the issue of the impending reversion of the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus with President Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor. Chow asserted that for the Chinese, the return of the islands was “a matter of nationalism,” pointing to the groundswell of anger from the intellectuals and people on the street in Taipei and Hong Kong, as well as the educated Chinese Diaspora in the US.107

Kissinger promised to look into the matter and asked the State Department to report back to him on the issue. When the report came back the next day with a statement of the US Department of State’s convoluted position, Kissinger wrote in the margin, “[b]ut that is nonsense since it gives islands to Japan. How can we get a more neutral position?”108 The more “neutral position” that Kissinger asked for did not materialize although his concern was explored. For in another message on June 8, 1971, the President’s Assistant for International Economic Affairs told the US Ambassador to the ROC in Taipei that “[a]fter lengthy discussion, the President’s decision on the Islands (Senkakus) is that the deal (of reverting back to Japan) has gone too far and too many commitments made to back off now.”109

|

Ethnic Chinese of the Baodiao Movement rallying against the Okinawa Reversion Treaty in Washington, D.C., in 1971. (Source: http://www.dushi.ca/tor/news/bencandy.php/fid11/lgngbk/aid27036) |

The strategic ambiguity the US maintains with regard to the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus apparently worked for decades. But after Japan announced its intention to “buy” and nationalize three of the islands, the US State Department was repeatedly questioned about its position on the issue. Finally a report was ordered by the US Congress during the escalation of the dispute to clarify US treaty obligations. The September 25, 2012, report re-validated the position of US neutrality on the question of sovereignty and US protection of the Senkakus under Article 5.110 Additionally, the Webb Amendment reaffirming the commitment to Japan under Article 5 of the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty was for the first time attached to a bill, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013, and officially approved by the Senate on November 29, 2012.111

However, the inherent contradictions posed by this US position became much more apparent after Japan’s purchase. If the purchase is legal, and the US recognizes the islands’ protection to be required under the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty itself, as with other territories of Japan, this would contradict the historical US stance of neutrality it has carefully maintained all these years.But, if, as the US still affirms, the Senkakus remains merely under the extended deterrence of Article 5, this means the US does not recognize the actuality and legality of the purchase, since Article 5 covers only “territories under the administration of Japan.”Thus the US is in danger of reducing Japan’s acquisition to a “farce,”112 a word the PRC uses now to describe the purchase or the nationalization act.

The Question of Residual Sovereignty

Despite the fact that this Treaty does not resolve the sovereignty issue, Japan believes it retains “residual sovereignty” over the Senkakus, a view that was seemingly corroborated by Dulles during the SFPT negotiations. Dulles, of course, did not talk about residual sovereignty of the Senkakus in particular so much as that of “Nansei Shoto” as a whole. Rogers at the Okinawa Reversion Treaty Hearing in 1971 sought to explicate what Dulles meant: the term “residual sovereignty” referred to the US intention and policy of returning all territories that it administered to Japan pursuant to Article 3 of the SFPT.113 Rogers’ explication was not necessarily an ex post facto rationalization. Even before the congressional hearing and the reversion, it was the US position that “the treaty alone is not necessarily the final determinant of the sovereignty issue.” 114 Therefore, if residual sovereignty pertaining to the Senkakus exists, Japan needed to have had indisputable title over the islands at the beginning of the trusteeship in 1952.As Japan has not definitively established it ever had sovereignty over the Senkakus, it must be concluded that the island group’s status remained indeterminate at the transfer of administrative control.

IV Effective Possession/Control Revisited

As the preceding discussion demonstrates, Japan cannot firmly establish grounds for the claim to the Senkakus based on modalities of territorial acquisition or principles of treaty interpretation in international law.In fact, while it declares international law to be on its side, there is much to show that Japan does not adhere to the bedrock principle of applying international law in good faith, tailoring, instead, the interpretation of legal concepts and doctrines to fit its needs and to bolster its position.In this section, pertinent cases of adjudicated international territorial disputes will be analyzed to determine whether Japan’s claim has stronger support from case law.115

Justifications for territorial claims before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) can generally be grouped into categories, with “effective control” being one Sumner finds in an overview to be highly determinative in judicial decisions.116 Most scholars too believe effective control to be “…the shibboleth – indeed, the sine qua non – of a strong territorial claim.”117 Analyzing island disputes only, Heflin arrives at a similar conclusion, i.e. that effective control is not only determinative but may be dispositive in these cases.118 As the concept coincides with and is indistinguishable from the previously discussed concepts of effective occupation and effective possession, the terms effective control, possession and occupation will be used interchangeably in this section.

Japan’s claim to “valid control” of the Senkakus begins at the incorporation date of January 14, 1895.This is the date it has chosen to mark the origin of the claim and therefore of the dispute.Whether the ICJ would focus on this “critical date” in a legal sense, in which acts occurring subsequent to the date “will normally be held as devoid of any legal significance,”119 is uncertain. The date, however, conveniently divides the dispute into two distinct periods, namely, pre- and post-January 14, 1895, and an examination of one without the other would be incomplete.

The Permanent Court of International Justice’s (PCIJ) decision in a 1933 case most resembling the island dispute in the period leading up to the date of January 14, 1895, is the Eastern Greenland Case.120 Although the case does not involve uninhabited islands, Greenland falls into a class of territories that are barren, inhospitable and not conducive to settlement, in this respect similar to the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus or the Arctic and Polar regions. In such disputes, much less is required to demonstrate intent to occupy and exercise effective control/possession.

In this Case, both Norway and Denmark claimed sovereignty over Eastern Greenland.Norway occupied the territory following a royal proclamation on July 10, 1931, asserting the territory was terra nullius. It argued that Eastern Greenland lay outside the boundaries of Denmark’s other occupied colonies in Greenland. Denmark, on the other hand, maintained it had sovereignty over all of Greenland and that Norway’s proclamation was invalid because it violated the legal status quo.Denmark contended that its title up to 1931 was “founded on the peaceful and continuous display of State authority over the island,” uncontested by any other state.121

The Court in its deliberations notably established a “critical date” which was determined to be the date of Norway’s royal proclamation. At this critical date, the dispute was not one of competing sovereignty claims. Rather as Sharma points out “[i]t was a case where one party was insisting upon a claim to sovereignty over the territory in question, whereas the other party was contending that the disputed territory had always remained ‘no man’s land’.”122

The PCIJ ruled in favor of Denmark. In essence, the Court concluded that Denmark’s demonstration of sovereignty over Greenland as a whole for the period preceding the critical date in 1931 was sufficient to establish its valid title to Eastern Greenland.123 In other words, in sparsely settled land sovereignty need not be displayed in every nook and corner of the territory so much as over the territory as a whole. Thus the criterion of effective possession/control was applied and was not set aside by the Court in this case so much as adapted to the conditions of a different environment and circumstance. In inaccessible Greenland, effective occupation was essential but very little display and exercise of state authority was required to satisfy this principle.

Norway’s claim that the land was terra nullius did not convince the Court since Norway had made little effort to claim Eastern Greenland prior to the critical date. And although Denmark might not have been in actual and effective control of Eastern Greenland or even Greenland as a whole, Norway had shown even less control, having hardly any activity through different historical periods.124 In the absence of any competing claims up to 1931, one scholar commented that Denmark “succeeded largely by default.” 125

Scholars examining arbitral and judicial decisions pertaining to island disputes generally consider the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus controversy to be a case of competing sovereignty claims. The question follows as to whether this characterization of competing claims is appropriate or whether, like the Eastern Greenland Case, the characterization of the dispute to be a claim of sovereignty versus one of terra nullius is more appropriate. If the latter, then perhaps China has the more colorable claim. For China can furnish evidence of the exercise of state authority over Taiwan, which administered Diaoyu Dao during the pre-January 14, 1895, period; the islands’ being administered by Taiwan in turn was arguably established in the aforementioned historical documents of gazetteers/annals. The Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus dispute, however, was not submitted for arbitration shortly after the dispute arose as in the Eastern Greenland Case. The succeeding period from 1895 on, during which Japan has had de facto control of the Senkakus, would have to be evaluated as well for applicable judicial rulings that may provide a better guide for analyzing the dispute.

According to most scholars the most authoritative case law on title creation and preservation can be found in the 1928 Island of Palmas Case.126 In this Case the US and the Netherlands each laid claim to a sparsely inhabited island off the coast of the Philippines. The US claimed it had acquired a historical title through Spain’s cession of the island and the Philippines in a treaty after US victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898.Spain, in turn, had discovered the island in the 16th century. The Netherlands, on the other hand, claimed the island on the basis of effective possession and exercises of state functions beginning in 1677 or even earlier.

The Netherlands was awarded the title, with the Permanent Court of Arbitration stressing that not only must title be acquired, it must also be sustained through effective possession/control according to standards developed since the acquisition of title. This means “[t]he existence of a right must be determined based on the law at the time of the creation of the right and the international law applicable to the continued existence of that right.”127 The contemporary standards of effective possession, derived from this Case and embossed in later rulings, regard the “continuous and peaceful display of territorial sovereignty (peaceful in relation to other states)” as crucial to title acquisition and preservation.128 This principle may have more weight in judicial and arbitral decisions on sovereignty claims than a title that was previously acquired. Some scholars, however, find the principle questionable, opining, “[e]very state would constantly be under the necessity of examining its title to each portion of its territory in order to determine whether a change in the law had necessitated, as it were, a reacquisition.”129

A crucial difference exists when comparing this case to that of the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus. Beginning in 1677, the Netherlands had exhibited over a century of state functions up to 1906 when the dispute arose, while the US had not. Japan had not exercised sovereignty over the Senkakus until its supposed incorporation in 1895, and its control of the Senkakus thereon was not continuous but was interrupted by the US administration of the islands between 1945 and 1972.Japan claims to have had “direct” control only from 1895 to 1945 and then again from 1972 to the present.130 That initial period would probably not be considered long enough to acquire title given that Japan displayed little or no activity before the incorporation date. However, according to the Court in the Island of Palmas Case, stipulating the exact length of time is less important than ensuring it should be long enough for a rival claimant to realize “the existence of a state of things contrary to its real or alleged rights.” 131 In theory and in case law, then, the importance of the claimant having constructive knowledge of a rival claim converges. Thus Japan’s secrecy which helped facilitate initial annexation of the islands might actually work against it in court.

The period 1972 to the present is even shorter. The question then becomes one of whether Japan exercises effective control/possession and whether the exercise is peaceful, without protest from China during this time. In order to answer this question, the activities which comprise administrative versus effective control/possession must first be explored. An analysis reveals that the definition of effective control/possession in international law overlaps considerably with the concept of the administration of a territory. For example, in the case of Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan, Indonesia and Malaysia presented competing claims to the islands of Litigan and Sipadan based on a number of factors such as history, treaty law and so on.132 The International Court of Justice found Malaysia’s exercise of effective control which consisted of “legislative, administrative or quasi-judicial acts” sufficient to award it the title.133 Thus, effective control may be said to include administrative acts and a range of other activities, while the exercise of administrative functions comprises part of effective control/possession/occupation. As a result of this overlap, the two, i.e., administrative and effective control, may appear on the surface to be interchangeable. But they are qualitatively different in the Diaoyu Dao/Senkakus dispute.In effect, the type of administrative control Japan has over the Senkakus cannot be equated with the type of effective control judicial courts used in the past to award sovereignty in other territorial disputes, as can be seen from the analysis below.