War, War Crimes, Power and Justice: Toward a Jurisprudence of Conscience

Richard Falk

Ever since German and Japanese leaders were prosecuted, convicted, and punished after World War II at Nuremberg and Tokyo, there has been a wide split at the core of the global effort to impose criminal accountability on those who commit crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, and war crimes on behalf of a sovereign state. The law is always expected to push toward consistency of application as a condition of its legitimacy. In the setting of international criminality the greatest danger to widely shared values is posed by those with the greatest power and wealth, and it is precisely these leaders that are least likely to be held responsible or to feel threatened by the prospect of being charged with international crimes. The global pattern of enforcement to date has been one in which the comparatively petty criminals are increasingly held to account while the Mafia bosses escape almost altogether from existing mechanisms of international accountability. Such double standards are too rarely acknowledged in discussions of international criminal law nor are their corrosive effects considered, but once understood, it becomes clear that this pattern seriously compromises the claim that international criminal law is capable of achieving global justice.

Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Tribunals

In a sense the pattern of double standards was encoded immediately after World War II in the seminal undertakings at Nuremberg and Tokyo that assumed the partially discrediting form of ‘victors’ justice’ in the weak sense of the term. The strong sense of victors’ justice involves imposing punishment on those who are innocent of substantive wrongdoing beyond the misfortune of being on the losing side in a war. The weak sense is that the implementation of international criminal law is undertaken only against individuals on the losing side who are indeed responsible for substantive wrongdoing, while exempting seemingly guilty individuals on the winning side. This results in double standards that weaken claims to be acting on the basis of the rule of law. Nevertheless, the possibility often, but not always, exists of sentencing procedures that can be sensitive to different degrees of criminality. Some efforts can and should be made to close the gap between law as vengeance and law as justice. The prospects of securing justice vary from case to case and tribunal to tribunal, depending on the context and auspices.

The Atomic Bomb Attacks

Yet even a weak sense of victors’ justice is not a minor flaw, its unacceptable inequality of enforcement aside. It may act to exempt even the most severe and harmful forms of criminal behavior from legal scrutiny, and thereby badly confuse our understanding of the distinction between criminal and non-criminal activity. Surely the indiscriminate bombings of German and Japanese cities by Allied bomber fleets—no less than German and Japanese indiscriminate bombing of Britain and China—and the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were ‘crimes’ that should have been investigated and prosecuted if the tribunals had been truly ‘legal’ in the sense of imposing individual accountability on both victors and vanquished for their combat operations.

What is more, by refusing to prosecute victors, their substantive ‘crimes’ attained a kind of perverse de facto legality. There is little doubt that had Germany or Japan developed the atomic bomb first, and then used it, the individuals responsible would have been charged with and convicted of crimes against humanity and war crimes by the victorious allied powers, and their behavior stigmatized in the annals of customary international law.

The one judicial body to pass judgment on the atomic bomb attacks on Japanese cities was a lower Tokyo court in the Shimoda decision handed down on December 7, 1963, that is, with a subtle touch of Japanese humility, the exact day of the 22nd anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attacks.

|

US battleship sinks at Pearl Harbor |

The decision, relying on expert testimony by respected Japanese specialists in international law, did conclude that the attacks on large cities violated existing international law because of their indiscriminate and toxic characteristics. The case had been initiated by survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who sought nominal damages and lacked any legal standing to put forward criminal allegations.

As might have been expected Japan as a defeated state and one that remained subordinate to American military power and diplomatic influence, was not inclined to pursue the matter any further, and seemed precluded from doing so by the peace treaty with the United States. Not surprisingly the Shimoda judgment virtually disappeared down the memory hole of atomic diplomacy. In 1996 the International Court of Justice in an Advisory Opinion responding to a question put to it by the UN General Assembly narrowly defined the conditions under which it might possibly be lawful to resort to nuclear weapons in situations of extreme self-defense that if applied to the 1945 atomic attacks would definitely result in their criminalization. As far as is known no effort has been made by any nuclear weapons state to alter its doctrine governing threat and use, including the threat of nuclear annihilation, in light of this most authoritative assessment of the international law issues at stake by the World Court.

|

Firebombing of Tokyo MARCH 9-10, 1945 |

Had the defeated states used an atomic bomb and the perpetrators been charged and convicted, this might have made it somewhat more difficult for the victors to rely upon nuclear weaponry in the future, and might have encouraged them to work diligently and reasonably to negotiate a treaty regime of unconditional prohibition. Instead, the victorious United States Government has never been willing to express formally even remorse for these wartime atrocities that completely lacked the partially redeeming feature of military necessity. It has retained, developed, possessed, deployed, and threatened other nations with the use of nuclear weapons on numerous occasions, including the possibility of using weaponry with payloads many times the magnitude of those first bombs dropped on Japan. As well, having opened this ultimate Pandora’s Box, others have acquired the weaponry and relied upon its ultra-hazardous energy technology to produce nuclear power.

It is not just the inherent unfairness of victors’ justice, but its tendency to normalize unacceptable wartime behavior if done by the winning side in a major war, which nullifies the very possibility of a jurisprudence of conscience. The closest that the United States Government has come to acknowledge officially its culpability in relation to Hiroshima and Nagasaki was contained in a single line in Barack Obama’s speech of April 5, 2009 in Prague that envisioned a world without nuclear weapons: “…as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act.” Unfortunately, such a sentiment was neither a belated apology nor was it repeated in Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech a few months later, nor have any concrete steps been taken to initiate a nuclear disarmament process in the course of the Obama administration.

Fairness of Procedure

|

Tokyo Trial |

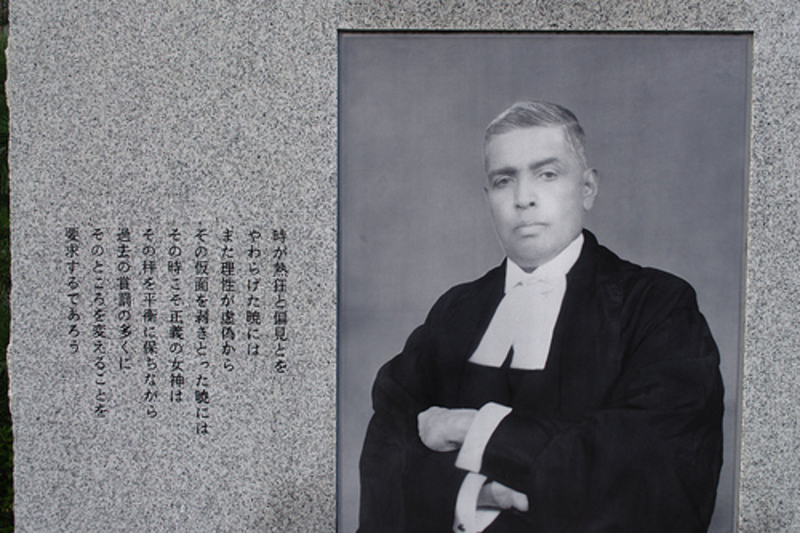

There are important matters of degree that either mitigate or aggravate the contention of victors’ justice. It was the case, especially in Tokyo, that the tribunal allowed defendants to be represented by competent lawyers and that the judges assessed fairly the evidence against defendants that alleged criminality. The Tokyo process even produced a celebrated dissenting opinion by the Indian jurist, Radhabinod Pal, and three Nazi defendants were acquitted by the Nuremberg tribunal. In short, there was a measure of procedural fairness in these trials. It seems clear that Justice Pal’s long dissenting opinion came as an unpleasant surprise to those who had arranged the tribunal. After all, Pal questioned in form and substance the overall legitimacy of what he believed to be a one-sided prosecutorial approach to the administration of criminal justice. He particularly lamented the failure of the court to take into account the Japanese rationale for recourse to war, especially the damaging impacts of coercive encirclement of Japan by American grand strategy, which was perceived by Japanese leaders, reasonably in Pal’s understanding, as threatening the viability of the country. Pal also did little to hide his contempt for colonial powers sitting in judgment of the behavior of an Asian country. I suppose it is part of the educative function of victors’ justice in a liberal society to note that it became almost impossible for many years to obtain a copy of Judge Pal’s exhaustively reasoned rejection of the major premise of the Tokyo war crimes tribunal.1

|

Japanese Commemoration of Justice Pal |

Selectively Prosecuting the Guilty

Without doubt those who were accused of these international crimes at Nuremberg and Tokyo did engage in activity that could in many instances be properly be viewed as morally depraved, as well as criminal and deserving of punishment. And it was deemed relevant to constructing a peaceful world order at the time to send a clear signal to future political leaders and military commanders that they would be henceforth held criminally responsible for their behavior, and could no longer hide behind claims of sovereign immunity and superior orders. But such a signal as delivered conveyed, at best, an ambiguous message to the extent that it seemed that future victors in major wars were likely to continue to avoid accountability even if they appeared to be manifestly guilty of committing international crimes.

This split notion of accountability as between winners and losers remains descriptive of how international criminal law is currently implemented. Indeed, the gap has widened over time, or at least become more evident. This awareness is partly a result of increasing efforts by the inter-governmental system of states to hold losers and vulnerable political actors accountable while holding firm the exemption of the powerful and their friends. The NGO community has by and large been opportunistic, supporting efforts to hold officials accountable for their criminality without worrying too much about double standards and selective implementation, seeming to reason that a glass half full was to be preferred to an empty glass. This has had the unfortunate effect of seeming to legitimate the hierarchical character of world order. By ignoring the crimes of the powerful political actors on the world stage while applauding the criminal prosecution of weaker political actors, an attitude of normalcy or indifference becomes associated with double standards in international criminal law.

The recent trend has exhibited a gradual increase in the availability of international mechanisms to hold leaders accountable, including the establishment of a variety of special or ad hoc international tribunals, including those constituted by civil society initiatives, to address serious criminal allegations (former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, Japanese comfort women, indigenous peoples) relating to genocide and crimes against humanity.

Crimes Against Peace

A more permanent venue for some initiatives along these lines came into being in 2002 with the unexpected establishment of the International Criminal Court. For reasons relevant to the argument made here, the negotiations of the ICC had to stop short of incorporating crimes against peace into its claim of jurisdictional authority, reflecting the interest of major states in not acknowledging restrictions on their use of what geopolitically oriented diplomats call ‘the military option,’ which reflects a thinly disguised insistence on discretion to use force as an instrument of foreign policy despite the unconditional prohibitions of threats or uses of force in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. The recent Israel, American, and British military threats directed at Iran is a flagrant instance of relying on a non-defensive threat to use force against a sovereign state. By Nuremberg or Charter standards such threat diplomacy would appear to be a naked example of a crime against peace.

Again the issue of victors’ justice lurks in the background, but this time in a reverse relationship to that pertaining to the atomic bomb. Here the World War II tribunals were most intent at the time on criminalizing recourse to aggressive war, and were here on strong substantive grounds as both the European and Asian theaters of warfare were definitely initiated by the states that went on to lose the war and whose surviving leaders were being prosecuted. At Nuremberg, the judgment went out of its way to declare that crimes against peace are the worst possible offense against the law of nations, encompassing the lesser realities of crimes against humanity and war crimes, and except for Justice Pal, the judges in both tribunals had little trouble reaching such a legal conclusion.

It was this conclusion that underlay the original conception of the UN as being a war prevention institution (“to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” in the language of the preamble to the charter) whose charter restricted valid claims to use force to situations of self-defense against a prior armed attack or to occasions on which the Security Council mandated a use of force for the sake of international peace and security.

Despite such a legal foregrounding of this war prevention priority, the Security Council veto given to the winners in World War II conferred a permanent exemption from accountability of a sort that continued and widened the failure to hold the winners criminally accountable at Nuremberg or Tokyo. The practice of the UN has confirmed the refusal of these five permanent members of the Security Council, along with a few other states, to live according to the precepts of the charter. Indeed, they would bring geopolitical pressures to bear so that the Security Council, as it did a few months ago, would mandate an interventionary use of force in Libya that was neither defensive nor necessary for the sake of international peace and security.2 Because of its challenge to militarism and geopolitical reliance on force, crimes against peace has been basically marginalized as an international crime, supposedly because there was no agreement among governments as to a definition of aggression, but more genuinely, because geopolitical actors refused to accede to any formal challenge to their discretion to threaten and use force to resolve international conflicts or impose their political will. Here the leverage of geopolitical pressure keeps the legal precedent set at Nuremberg and Tokyo after World War II from becoming a behavioral norm. That is, it was appropriate to criminalize the aggression of Germany and Japan, but it is not acceptable to hamper the activities of geopolitical ‘peacekeepers’ by the application of such a restrictive norm to their behavior. At present, for instance, the standard American approach to its efforts to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear bomb is to announce with due gravity that the military option remains on the table, that is, a threat to initiate a non-defensive war. This threat is reinforced by a series of other coercive measures, including UN sanctions and diplomatic pressures on third parties to forego economic relations with Iran or to increase oil production so that Iran’s oil revenues will diminish. Such a package of measures is designed to achieve the diplomatic goal of Iran’s renunciation of its nuclear enrichment program.

Tribunals and Historical Validation

There were other messages to the world arising from these seminal war crimes trials at the end of World War II. For instance, the presentation of the case against the defendants was a way of prosecuting the losing states while vindicating the winners. It was a matter of certifying the justice by way of an extended judicial narrative that strengthened the moral credibility of the battlefield outcome. The winning side by conducting trials of this kind takes advantage of the opportunity to reinforce claims as to the justice of battlefield verdicts by pronouncing on the criminality of losers while overlooking the criminality of its own actions. This attempt to control the judgments of history is more influential with short-run public opinion than it is with historians who over time look more objectively at the evidence except to the extent blinkered by their national or civilizational orientations. It also tends to make occupation seem reasonable, as well as imposing restrictions on the future sovereignty of the defeated country.

But there were also short-term consequences of such a validation of the outcome of the war that extended beyond securing the peace. The validation provided cover for the establishment of more or less permanent American military bases in the Asia Pacific region, including in Okinawa, mainland Japan, and South Korea, as well as establishing strategic claims over the entire region and exerting direct control over Micronesia and other Pacific Islands. In effect, geopolitical expansionism and a triumphalist American grand strategy that extended its reach beyond maintaining peace in the region after 1945. Undoubtedly, the unquestioned accompaniment of holding the losers accountable and writing without critical commentary the official history of the war enabled this geopolitical project to go forward without debate, much less criticism. In effect, the dynamics of establishing World War II as a ‘just war’ prepared the ground for constructing what in some respect is an ‘unjust peace’ that has endured despite its serious compromising of the sovereignty of several Pacific states.

The Nuremberg Promise

There was also another deferred effect of victors’ justice that was sensitive to its challenge to the legitimacy of the original legal process. It made an attempt to overcome the flaw of double standards by offering an informal commitment to being evenhanded in the future. This gesture to remove criminal accountability from the domain of geopolitics can be labeled as ‘the Nuremberg promise,’ and involves a commitment by the victors in the future to abide by the norms and procedures used to punish the German and Japanese surviving military and political leaders. In effect, to correct this flaw associated with victors’ justice by converting criminal accountability from rule of power to rule of law applicable to all rather than a consequence of the outcome of wars or a reflection of geopolitical hierarchy.

The Chief Prosecutor at Nuremberg, Justice Robert Jackson (who had been excused temporarily from serving as a member of the U.S. Supreme Court), gave this promise an enduring relevance in his official statement to the court: “If certain acts and violations of treaties are crimes, they are crimes whether the United State does them or whether Germany does them. We are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us.” Peace activists frequently quote Jackson’s words, yet political leaders who take no notice of either the original flaw at Nuremberg or the obligation to remove it consistently ignore them. Jackson’s promise at Nuremberg was made in good faith, but its irrelevance to what evolved over time suggests that the rhetoric at the time was not sufficient to generate a sense of obligation on the part of American leaders who subsequently acted on behalf of the United States.

A parallel issue arises in relation to the willingness of a defeated country to accept the criminalization of its leadership. The German philosopher, Karl Jaspers in his The Future of German Guilt argued that the acceptability of these convictions and punishments of German leaders would have to wait until it becomes clear in the future whether the Nuremberg promise was going to be kept by the victors. If the promise was broken then in retrospect the Nuremberg process should be treated as a legal form of vengeance rather than an expression of criminal justice. Taking Jaspers seriously in this respect would raise questions about the liberal embrace of international criminal law despite its incorporation of double standards.

Since 1945 crimes by the victors in conflict, along with other geopolitical actors of regional ambition, have continued to be overlooked by international criminal law, while prosecutions reflecting geopolitical leverage have been happening at an accelerating pace without any concerted intergovernmental or UN effort to correct the imbalance. Since the end of the Cold War implementation of criminal responsibility has been increasingly imposed on losers in world politics, including heads of state such as Slobodan Milosevic, Saddam Hussein, and Muammar Qaddafi each of whom were deposed by Western military force, and either summarily executed or prosecuted.3

Institutionalizing International Criminal Law

This dual pattern of criminal accountability that cannot be fully reconciled with law or legitimacy has given rise to several reformist efforts. Civil society and some governments have favored a less imperfect legalization of criminal accountability, and raised liberal hopes by extraordinary efforts of a global coalition of NGOs and the commitment of a group of middle powers in establishing the ICC despite the opposition of a geopolitical consensus. Fearful of losing or compromising their impunity, such geopolitical heavyweights as the United States, China, India, and Russia have refused to ratify the ICC, and the United States has gone further, pressuring over 100 countries to sign statements agreeing not to hand over to the ICC Americans accused at The Hague of international crimes.

The result is that this and other formal and informal initiatives have not yet seriously impinged on the hierarchal realities of world politics, which continue to exhibit an embrace of the Melian ethos when it comes to criminal accountability: “the strong do what they will, the weak do what they must.” Such an ethos marked, for Thucydides, unmistakable evidence of Athenian decline, but for contemporary realists a different reading has been prevalent. Underpinning political realism has been the premise that hard power calls the shots in history, and the losers have no choice but to cope as best they can. Double standards persist: those who are enemies of the West or evildoers in Africa are targets of global prosecutorial zeal, while those in the West who wage aggressive war or mandate torture as national policies continue to enjoy impunity as far as formal legal proceedings are concerned.

As suggested, the veto in the Security Council both complements the ‘naturalness’ of victors’ justice and is a prime instance of constitutionalizing double standards. The veto power, while sounding the death knell for the UN in its assigned role of ensuring war prevention based on law rather than geopolitics, is not without providing certain benefits to world order. This exit option for several major actors is probably responsible for allowing the Organization to achieve and maintain universality of membership even during times of intense geopolitical conflict. Without the veto, the West would have likely pushed the Soviet Union and China out the door during the Cold War years, and the UN would have lost its inclusive and universalist character in a manner similar to the discrediting of the League of Nations, an experience after the end of World War I that transformed Woodrow Wilson’s dream into a nightmare. Arguably the veto and victors’ justice are examples of Faustian bargains that enable a semblance of law and justice to be present in international life, and to convey the impression that there is a morally evolutionary process at work that introduces a gradually increasing measure of civility into the conduct of world politics. The question is whether this appearance of civility is to be treated as a form of moral progress, however slow or halting, or rather as the prostitution of law and institutions to geopolitical abuses and ambitions. There is no assurance that the evolution of international criminal law has any prospect of overcoming the current pattern of an open ended geopolitical right of exception.

Yet even this realist world of unequal states has been embodied imperfectly within the United Nations. So conceived, even if the UN is judged by way of a geopolitical optic, the anachronistic character of the 1945 Security Council persists as a remnant of the colonial era. This is delegitimizing. 2012 is not 1945, but the difficulty of achieving constitutional reform within the UN means that India, Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia, Germany, Japan, and South Africa seem destined to remain permanent ladies in waiting as the UN goes about its serious geopolitical business. What this means for UN authority, including its sponsorship of the politics of individual criminal accountability, is that all that is ‘legal’ is more often than not ‘illegitimate,’ and lacking in moral force.

My argument seeks to make two main points: first, double standards pervade the treatment of war crimes eroding the authority and legitimacy of international criminal law; and secondly, those geopolitical hierarchies that are embedded in the UN framework lose their authority and legitimacy by not adapting to changing times and conditions, especially the collapse of the colonial order and the rise of non-Western centers of soft and hard power. In this latter instance, it is the inability to reflect the geopolitical ratio of power that partially hampers the legitimacy of the UN, not its realist tendency to express its legitimacy by exhibiting in its procedures and structures the relative strength of political actors. This durability of the original UN distribution of authority in the Security Council both reflects the difficulty of overcoming formally entrenched positions of status and the political sense that the existing five permanent members maintain a certain internal balance geographically (West versus Asia) that remains reflective of world power relations despite the hegemonic role played by the United States within and outside of the UN. Of course, even if the UN enhanced its geopolitical legitimacy by taking account of global shifts in capabilities and influence, this would not necessarily pose a challenge to hierarchy and double standards.

Universal Jurisdiction

There are different kinds of initiatives taken to close this gap between the legal and the legitimate in relation to the criminality of political leaders and military commanders. One move is at the level of the sovereign state, which is to encourage domestic criminal law to extend its reach to cover international crimes. Such authority is known as Universal Jurisdiction (UJ), a hallowed effort by states to overcome the enforcement weaknesses of international law, initially developed to deal with the crime of piracy, which being interpreted as a crime against the whole world could be prosecuted anywhere regardless of where the pirate operated. Many liberal democracies in particular have regarded themselves to varying degrees as agents of the international legal order as well as providing for the rule of law for relations within their national boundaries. This has led governments to endow their judicial systems with some authority to apprehend and prosecute those viewed as criminally responsible for crimes of state even if the criminal acts were performed outside of geographic boundaries. The legislating of UJ represented a strong tendency during the latter half of the twentieth century in the liberal democracies, especially in Western Europe to be proactive with respect to the implementation of international criminal law by escaping to some extent from the constraints of geography.

This development reached public awareness in relation to the dramatic 1998 detention in Britain of Augusto Pinochet, former ruler of Chile, in response to an extradition request from Spain where criminal charges had been judicially approved. The ambit of UJ is wider than its formal implementation as its mere threat is intimidating, leading those prominent individuals who might be detained and charged to avoid visits to countries where such claims might be plausibly made. In late 2011 George W. Bush cancelled a speaking engagement in Switzerland because of indications that he might be arrested and charged with international crimes if he ventured across the Swiss borders. Similar reports have suggested that high Israeli officials have changed travel plans in response to warnings that they could face arrest, detention or extradition for alleged crimes, especially in recent years those associated with either the Lebanon War of 2006 or the 2008-09 Israeli military attack on Gaza bearing the code name of Operation Cast Lead. In other words, the possibility of an assertion of UJ may have a behavioral and psychological impact even if the defendant is not brought physically before the court to stand trial.

|

Pinochet brought to trial |

As might be expected, UJ gave rise to a vigorous geopolitical campaign of pushback, especially by the governments of the United States and Israel. These governments exhibited the most anxiety that their leaders might be subject to criminal apprehension by foreign national courts even in countries that were political friends. As a result of intense pressures, several of the European UJ states have rolled back their legislation in response to Washington’s demands, thereby calming somewhat the worries of travelers with records of public service on behalf of their countries that was potentially vulnerable to criminal prosecutions in foreign courts!

Civil Society Tribunals

There is another approach to spreading the net of criminal accountability that has been taken, remains controversial, and yet seems responsive to the current global atmosphere of populist discontent. It involves claims by civil society, by the peoples of the world, to establish institutions and procedures designed to close the gap between law and legitimacy in relation to the application of international criminal law. Such initiatives can be traced back to the 1966-67 establishment of the Bertrand Russell International Criminal Tribunal that examined charges of aggression and war crimes associated with the American role in the Vietnam War. The charges were weighed by a distinguished jury of private citizens composed of moral and cultural authority figures headed by Jean-Paul Sartre. The Russell Tribunal was derided by critics at the time as a ‘kangaroo court’ or a ‘circus’ because its legal conclusions were predetermined, and amounted to foregone conclusions. The critics condemned this initiative on several overlapping grounds: that its outcome could be accurately anticipated in advance, that its authority was self-proclaimed and without governmental approval, that it had no control over those accused, that its proceedings were one-sided, and that its capabilities fell far short of enforcement.

What was overlooked in such criticism was the degree to which this dismissal of the Russell experiment reflected the monopolistic and self-serving claims of the state and state system to control the administration of law, ignoring the contrary claims of society to have law administered fairly in accord with justice, or at least to expose its distortions and double standards. Also ignored by the critics was the fact that only such spontaneous initiatives of concerned persons and groups could overcome the blackout of truth on the matters of criminality achieved by the geopolitics of impunity. The Russell Tribunal may not have been ‘legal’ understood in the sense of deriving its authority from the state or from international organizations, but it was ‘legitimate’ in responding to double standards, by calling attention to massive crimes and dangerous criminals who otherwise might enjoy a free pass, and by producing a generally reliable and comprehensive narrative account of criminal patterns of wrongdoing and flagrant violations of international law that destroy or disrupt the lives of entire societies and millions of people. Such societal initiatives require great efforts that lack the benefit of public funding, and only occur where the criminality being legally condemned seems severe and extreme, and where geopolitical forces effectively preclude systematic inquiry by established institutions of criminal law.4

It is against this background that we understand a steady stream of initiatives that build upon the Russell experience in the 1960s. Starting in 1979, the Basso Foundation in Rome sponsored a series of such proceedings under the rubric of the Permanent Peoples Tribunal that explored a wide variety of unattended criminal wrongs, including dispossession of indigenous peoples, the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines, massacres of Armenians, and self-determination claims of oppressed peoples in Central America and elsewhere. In 2005 the Istanbul World Tribunal on Iraq examined contentions of aggression and crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, and war crimes associated with the U.S./UK invasion and occupation of Iraq, commencing in 2003, causing as many as one million Iraqis to lose their lives, and several million to be permanently displaced from home and country.5

In November 2011 the Russell Tribunal on Palestine, a direct institutional descendant of the original Russell undertaking, held a session in South Africa to investigate charges of apartheid, as a crime against humanity, being made against Israel. A few days later, the Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Tribunal launched an inquiry into charges of criminality made against George W. Bush and Tony Blair for their roles in planning, initiating, and prosecuting the Iraq War, to be followed a year later by a subsequent inquiry into torture charges made against Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Alberto Gonzales.6

Without doubt such societal efforts to bring at large war criminals to symbolic justice should become a feature of the growing demand around the world for real global democracy sustained by a rule of law that does not exempt from criminal accountability the rich and powerful whether they are acting internally or internationally.

Conclusion

The problems of victors’ justice and double standards pervade and subvert the proper application of international law. As long as power, influence, and diplomatic skills are unevenly divided, there will be some tendency for this to happen. Civil society is seeking to increase the ethical and political relevance of international law in two ways: by illuminating the geopolitical manipulation of law and by forming its own parallel institutions that focus on the criminality of the strong and the victimization of the weak. There remain many obstacles on this road to global justice, but at least some clearing of the geopolitical debris is beginning to take place. By geopolitical debris is meant this opportunistic reliance on law when it serves the interests of the powerful and victorious, and its determined avoidance and suppression whenever it restrains or censures their behavior. Until international law has the capacity to treat equals equally the corrective checks of progressive civil society are a vital ingredient of a jurisprudence of conscience despite their lack of governmental legitimacy.7

Richard Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law, Princeton University, and United Nations Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur for the Occupied Palestinian Territories. His recent books include Richard Falk and Mark Juergensmeyer, eds., Legality and Legitimacy in Global Affairs and Richard Falk and David Krieger, The Path to Zero: Dialogues on Nuclear Danger.

Recommended citation: Richard Falk, ‘War, War Crimes, Power and Justice: Toward a Jurisprudence of Conscience,’

The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 10, Issue 4 No 3, January 23, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

Yuki Tanaka and Richard Falk, The Atomic Bombing, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and the Shimoda Case: Lessons for Anti-Nuclear Legal Movements

Daniel Ellsberg, Building a Better Bomb: Reflections on the Atomic Bomb, the Hydrogen Bomb, and the Neutron Bomb

Marilyn B. Young, Bombing Civilians: An American Tradition

Peter J. Kuznick, The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb and the Apocalyptic Narrative

Mark Selden, A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq

Notes

I would like to thank Mark Selden for his editorial and substantive contributions this text, and to Ayca Cubukcu for her most thoughtful comments on an initial draft.

1 International Military Tribunal for the Far East: Dissentient judgment of Justice R. B. Pal (Calcutta: Sanyal, 1953).

2 The authorizing resolution of the Security Council seemed limited to providing humanitarian protection to the civilian population of the Libyan city of Benghazi,

but was operationally expanded by NATO to include a full-scale military air effort

to tip the balance in an internal civil war in favor of the anti-Qaddafi forces. UN Security Council Resolution 1973, 17 March 2011 was officially delimited as establishing a ‘No-Fly-Zone’ over Libya, although there was accompanying language that should never have been accepted by the five abstaining states to the effect that ‘all necessary measures’ were approved.

3 In Qaddafi’s case he was brutally killed by the military forces that captured him in his home town of Sirte on 20 October 2011.

4 Investigative journalism does act as a partial complement to these efforts of citizens’ tribunals. In Vietnam, for instance, Seymour Hersh made a notable contribution by exposing the execution by American military personnel of Vietnamese villagers. See Seymour M. Hersh, Mylai 4: a report on the massacre and its aftermath (New York: Random House, 1970)

5 See Müge Gürsöy Sökmen, ed., World Tribunal on Iraq: making the case against the war (Northhampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2008)

6 I have written blog posts on both of these initiatives. Falk, “Israel and Apartheid? Reflections on the Russell Tribunal on Palestine Session in South Africa,” Falk, “Kuala Lumpur War Crimes Tribuanal: Bush and Blair Guilty.”

7 There is a need to clarify what is meant by ‘a jurisprudence of conscience’ beyond the narrow claim of this article that law should treat equally all offenders of norms of international criminal law. It is true that many who subjectively act on the basis of their conscience engage in behavior that from other societal perspectives constitute crimes. For instance, the assassination of doctors who perform abortions by right to life advocates offers one clear illustration.