Since the turn of the millennium, emphasis on bodily perfection has become increasingly central to the media industries of South Korea (henceforth Korea), and a focus on ideal bodies has permeated popular discourse more generally.1 Although views on physical appearance built on longstanding notions of its importance in announcing status continue to be informed by a patriarchal order, a palpably intensifying commodification of the body in Korea’s media-saturated, consumer capitalist culture is giving rise to newer concepts of corporeal self-discipline and reconfiguring not only of how ‘beauty’, ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ are represented, but how the modern national self is understood.

While Connell (2005) has argued that multiple “masculinities” are produced in relation to “femininities,” she also asserts that mechanics of power create hegemonic versions of masculinity and femininity. Such paradigms of gender performance are disseminated in manifold modes from everyday discourse to literary and screen narrative, but in this

In this paper we concentrate on two complementary phenomena that have surfaced in the last decade, a focus in popular media on both muscled male torsos and long, slender female

|

These changes in the cultural landscape have been impelled by Korea’s expanding transnational connections and

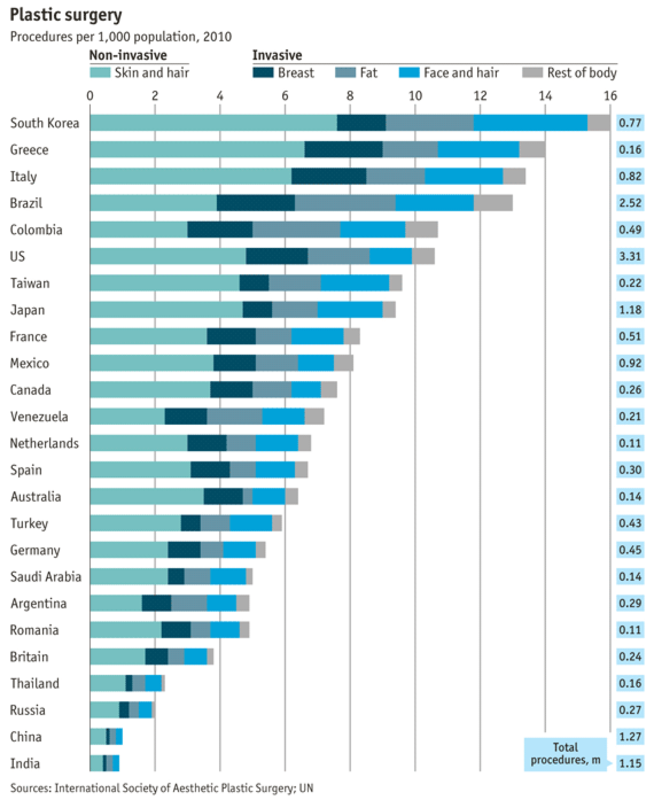

The graph at the right, which recently appeared in The Economist, details estimates on rates of cosmetic surgery in numerous countries, and reveals South Korea as having the highest national per capita involvement, if one takes into account both non-invasive (mole removal, Botox skin injections) and invasive procedures (blepharoplasty, breast augmentation, liposuction), as defined by the International Society

“Legs, Legs and More Legs”

In January 2011, Razor TV, a video outlet operated by Singapore’s Straits Times and self-described as stressing “hyper-local content,” uploaded a clip titled “Cleavage Out, Legs In?” Using a mélange of markedly Singaporean English and Mandarin, the clip focuses on the current attention to exposed female legs in Korean popular culture, opening with the following words:

Legs, legs and more legs. From Girls’ Generation to After School, 4Minute and Miss-A, it seems that no shorts or skirt is too tiny for these Korean girl groups. You can see them flaunting their long, flawless legs in music videos, concerts and TV performances, and even the cold winter didn’t deter them from doing so at these award ceremonies. These trend [sic] can also be seen in your favorite Korean dramas like ‘Swallow the Sun’ and ‘Personal Taste’, prompting a blogger to comment ‘Is anybody else concerned that this woman isn’t wearing pants?’ So what is this K-pop obsession with long legs all about? Find out on today’s Razor Pop. 5

With the term “trend,” the video references changing sensibilities in the intersection of appropriate bodily display and fashion, as well as the controversies that such transformations can invite. It is worth recalling, for example, that when singer Yoon Bok-hee popularized mini-skirts in the socially conservative atmosphere of 1960s Korea, governmental concerns with a potentially corrosive effect on public morals led to an ordinance banning skirts that rose more than ten centimeters above the knee (Chung 2012). Moreover, attention to a Korean trend from a Singaporean source that titles it an “obsession” reminds us that what constitutes noteworthy exposure of skin can vary significantly even in societies with relatively lax attitudes in this

|

The RazorTV clip, of course, draws its key inspiration from the remarkable rise of K-pop idol bands internationally in the last few years. In particular, we should note the successes of the genre in East and Southeast Asia, and especially Japan, with the noteworthy debuts of KARA and Girls’ Generation (Sonyŏ Shidae) there in 2010, which have precipitated striking instances of Korean media triumphalism.7 As Razor TV remarks, the association of K-pop girl groups specifically with long legs and bare thighs derived an especial boost from the choreography and costuming of Girls’ Generation in their 2009 music video “Tell Me Your Wish” (Sowŏnǔl

“Chocolate Abs”

This circulation of imagery via the

|

In the last decade, the exposed nude torso has become a near requisite for male “talents”—not only relative unknowns attempting to promote themselves in commercial media through their looks, but also well-known male stars hoping to maintain their

A 2009 television commercial for Market O’s riŏl pǔrauni (“real brownie”) well exemplifies the visceral effect of such images. Two young women carrying a box of brownies encounter a life-size billboard in a subway arcade featuring shirtless members of the K-pop band 2PM. The women have a debate about whether their impressively contoured abdominal muscles are real, and the skeptical one reaches to touch the pictured flesh of band member Nichkhun.8 As her finger presses into the abs that she so admires, Nichkhun comes alive and states,

The advertisement thus promotes the popularization of the term “chocolate abs” by equating the authenticity of the band’s muscles with that of the chocolate in its product.9 But the role of touch in the ad and YouTube user fan reaction also demonstrate the haptic eroticism of torsos and their powerful ability to evoke fantasies to caress and consume:

Epiikhiigh: “Oh my goodness, the abs, oh the abs!~;_; ♥ Haha, I wish I poked a picture of 2PM and they came alive, LMFAO._ Oh man, that would be pretty sweet :D,”

vanderwoodsen 90:“I want to eat those

|

We may observe the incipient growth in influence of this physique in the disjuncture between the representation of former

Bae’s transformation responds to the burst in popularity of images of the male torso during the World Cup year of 2002 and a contemporaneous rise in the discourse of

|

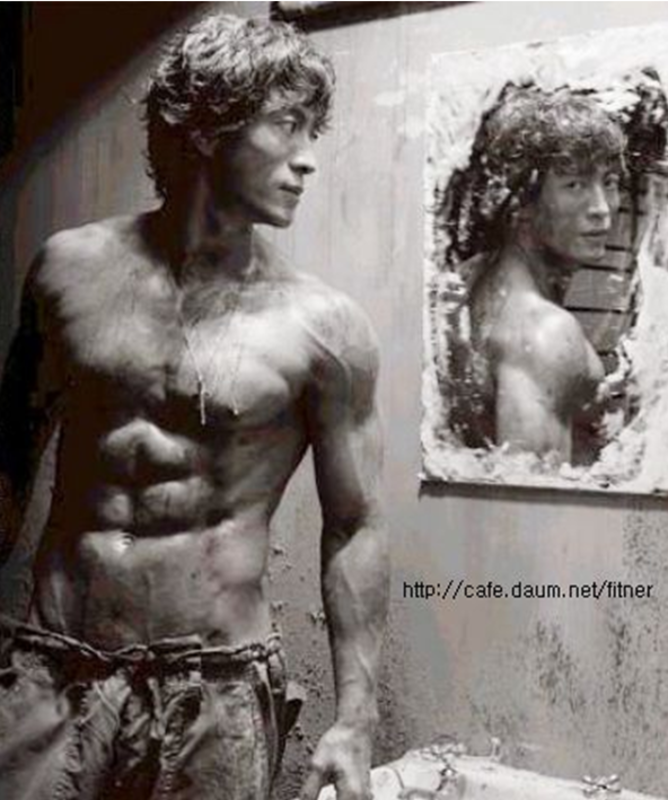

The trend for exposed torsos can also be linked with the rise to superstardom of K-pop performer Rain (Bi),10 whose image is intimately associated with the display of his naked abdomen, and whose physique played a role in propelling him to crossover success in dramas and film. At the climax of Rain’s concerts, the heavens appear to burst forth from above the stage, showers careening over him as he assumes an intense, broodingly heroic, and, to be sure, semi-nude posture.

|

The global popularity of Rain and his shirtless torso contributed to generating a new standard for K-pop’s male performers, transforming the body itself into the primary stage prop. Likewise, the performances of boy bands in music videos, as they expose their “chocolate abs,” often include choreographed stripping and abdominal waves or “popping” moves that direct the gaze to the torso in order to maximize and extend viewer excitement.11 One may readily chart this change in K-pop by comparing the appearance of boy band H.O.T., reigning princes of the genre from the latter half of the 1990s until they broke up in 2001, with that of current favorites 2AM.

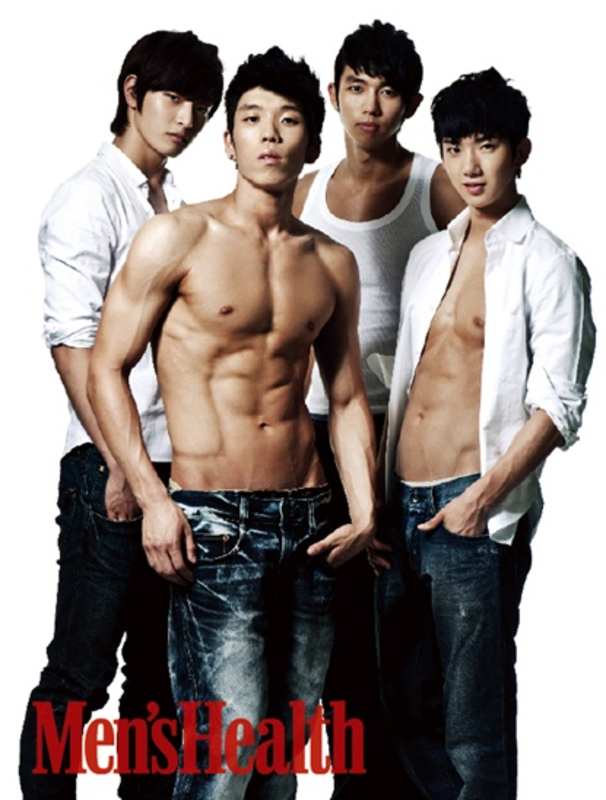

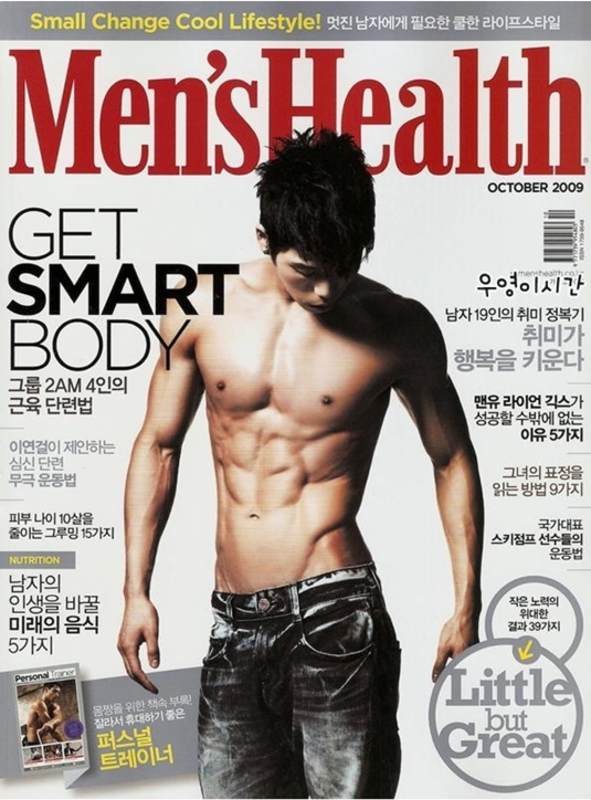

Whereas H.O.T.’s oversized shirts cover lithe torsos from which skinny arms protrude, 2AM releases pop confections that seem designed above all to showcase strutting shirtless bodies. A feature on the band in the October 2009 issue of Men’s Health details their workout regimen, which comes to be seen as a central aspect of their celebrity value.

In addition to Changmin, depicted to the right below, each of the group’s other members has had his torso featured on the cover of Men’s Health in the last few years, which indicates how the commercialized culture of stardom itself is becoming critical to defining the ideal male physical form.

|

These changing body ideals index changing socio-economic contexts in South Korea. Dyer (1982) has argued that the power of the body in the sporting realm represents economic might in demonstrating that people have more leisure and financial resources to care for the self.12 Jesook Song (2009) connects a rising industry of concern for health (

|

National Erotics

The naked torso and exposed legs thus operate as consumer fetish, encouraging desires to both

Global sport offers an important example of the connection between the sculpted torso and the nation, as the physique of the Korean athlete comes to serve as a metonym for the collective “body public.” The well-developed frames of Korean baseball players and swimmer Park Tae Hwan offer proof of physical supremacy on the putatively meritocratic field of global competition. These athletes not only put their bodily attributes on display, they are challenged to show dominance in international events through strength, skill, and endurance. Competitive sports are often thought to establish a “real,” “proven,” and “useful” masculinity as opposed to one achieved through steroid use, excessive gym time, photoshopped images, or stage paint. Representations of the hard male

The current ideological force of this body also responds to a century’s worth of emasculating representations of Korean masculinity arising from Japanese colonial power and American military occupation. Having finally “caught up” to other nations, in terms of not merely economic, but also physical power, hard male musculature symbolizes Korean global might. During the build-up to the 2002 World Cup semi-final match against Germany, a height comparison of the teams revealed that the Koreans were nearly a foot shorter on average than the Germans. A jocular but heartfelt riposte to this discrepancy was “smaller peppers are spicier,” with a reference to the common Korean meaning of pepper (

In a country whose government and institutions have been focused on achieving status at a global level, the popularity of the nude masculine torso readily lends itself to interpretation within evolutionary discourses of economic development. As athletic Korean male bodies resemble counterparts from the “West,” the “Rest” serves to represent an earlier stage in Korea’s history.13 The muscled abdomen attests to the achievements of Korean masculinity within an era of international competition and thus conveys Korea’s global might. In appealing to local consumers, the toned Korean male physique generates excitement for the nation (see Joo 2012, Chapter 3; Kim 2004). Swimmer Park Tae Hwan’s gold medal performance in the 2008 Beijing Olympics intensified national excitement over his powerful physique not only because he won Korea’s first medal in the sport, but also because his exposed body offered visual proof that Korean men could compete equally in terms of size and strength with elite swimmers the world over.

What, then, of female legs? Whereas we have drawn on transnational explanations for the increased focus on the nude male torso within Korea, we now shift discussion towards reception outside Korea in looking at this “transnational economy of erotic desire,” for a nuanced view of these phenomena also urges consideration of how these changing ideals are perceived from locale to locale and audience to audience. Although the Razor TV clip discussed above goes on to state that K-pop girl groups’ long legs have “captured the hearts of male and female fans alike all across Asia,” one may reasonably assume a varied response to bodily display according to such factors as national provenance, gender, age, religious background, sexual orientation, and so on.

Therefore, much as we engage with a legacy of emasculating representations of Korean males, let us also consider a parallel fascination with the legs of Girls’ Generation (Sonyŏ Shidae, or SNSD) in their 2010 debut in Japan. Given Korea’s fraught colonial history with Japan, and the presence of such hot-button issues as ongoing Japanese sex tourism in Korea and the unresolved matter of compensation for comfort women (see, e.g., Dudden and Mizoguchi 2007), the sexualized representation of Korean women in a Japanese context becomes almost ipso facto problematic. Indeed, the adulation that Girls’ Generation experienced in Japan as icons of desirable femininity appears at first glance to resuscitate sexualized (neo)colonial images of Korea, yet a closer look suggests instead, we would argue, shifting relationships of power in Northeast Asia’s cultural marketplace.

Translations of Japanese tweets that were uploaded on the popular English-language website allkpop.com immediately after the Tokyo debut of Girls’ Generation in August 2010 made it clear that many among the Japanese audience were extremely impressed with the performance in itself, albeit often from a position of self-confessed prior ignorance (cf. Yamanaka 2010): “This morning I was shocked by the high quality of the Korean idol group SNSD. They have a whole different presence”, wrote one user, while another asked very simply, “Is

As made evident by this latter comment, though, and another that states “as u read here, most of their fans are girls—so that that [sic] haterz~”, this transnational sexual attraction is rendered complex. Contrary to the expectations of SM Entertainment, whose CEO Lee Soo-man has gone on record as saying that they targeted men in their thirties and forties in marketing the group,14 SNSD’s predominant fan base in Japan has been females in their teens and early twenties. The Korean media have been particularly keen to report on both Japanese media accounts of Korean girl group success within Japan generally and to note this latter unanticipated feature in particular: a Sports Seoul piece details not only the rivalry among Japanese press outlets to cover the showcase debut of Girls’ Generation, carefully enumerating several of the major players involved, but the overwhelming prevalence of young females in the event’s audience, accompanying the article with shots of numerous fans clad as members of Girls’ Generation, frequently wearing the group’s signature hot pants.

|

|

In a similar piece of self-reflexive reportage, the

The celebration of Korean girl groups’ success in Japan extends from

Of course, it is hardly astonishing that Korean girl groups’ upper thigh exposure may thus also fuel prurient fantasies, and one can find business interests in the Japanese market happy to capitalize on them, as in a local adult video entitled “Beautiful Legs Legend” which plays off of Girls’ Generation’s nickname and outfits for “Genie”, and whose PG-13 rated opening sequence is available on YouTube. It remains unclear, however, to what extent or in what combinations the inspiration for the more risqué activity that follows in the film draws on a fetishization of a formerly colonized nation’s women, the eye-catching uniforms worn by Girls’ Generation in the music video, legs as an erotic body part, or simply Japan’s common faux-celebrity pornographic genre. An epigone of the notorious 2005 Kenkanryu [“Hating the Korean Wave”] manga (Allen and Sakamoto 2007) suggested that performances on the casting couch had brought Korean girl group members to their current popular status. Unsurprisingly, anger was a common reaction among the Korean media and public, especially to this latter affront, all the more so in that an ongoing feature of Korean popular discourse about Japan (Epstein 2010) involves scandalized reactions to its “debased” sexual culture and a concomitant expression of national moral superiority. A message arises that not only are the nation’s girls sexier and more attractive, they also are more wholesome; in this contradictory moralizing discourse, colonial haunting becomes manifest.

Within the larger Asian

“The K-pop assault on European shores was trumpeted by a front-page story in the culture sections of the left-of-centre Le Monde and the right-wing Le Figaro. The latter made much of the ‘interminable legs’ and ‘mini-mini’ skirts of Girls’ Generation and, in less frivolous mode, said they signalled a kind of “total” pop: an impeccably executed mixture of relentless rhythms, choreography and fashion. (Slattery 2012)

Just as the hard male body conveys ideas of a “global and powerful Korea,” so too then have “interminable” bare female legs become a marketing tool and branding technique for an enticingly toned and “impeccably executed” Korea. The varied responses outlined above in the dissemination and reinterpretation of Korea’s national erotic power—triumph conjoined with anger at perceived slights in the context of Japan, a sense of superior liberalism vis-à-vis Thailand, and pride over Western acceptance that welcomes Korea to the company of advanced nations (sŏnjin’guk)—indicate the shifting comparative ideologies of moral and sexual standards that work in the service of proving Korea’s talent in multiple spheres.

The Narcissistic Turn

Nonetheless, such enthusiastic focus on physical form as a demonstration of national power has consequences. As the media concentration on the fashioning of Korean stars into icons of internationally desirable femininity indexes changing ideals of the body under the influence of capitalist consumerism, so too does it pressure individual females to manufacture themselves into objects of desirability within a competitive environment. Likewise, the bombardment of images of muscled male torsos in conjunction with underlying discourses of comparative economic development urges men toward emulation.

Because of the gendering of the public gaze, however, the pressures inculcated by the pervasive portrayal of these bodies in a media-saturated society have worked in rather different directions. Certainly for female stars themselves, display of attractive legs transmutes from a selling point to a point of constant surveillance.16 Calculated display and “showing off” for the international gaze become repeated tropes and we encounter a “

Furthermore, when curious fans and casual consumers are given “special” insight by commercial media into how the members of girl groups maintain their striking

The Daum café site

Nonetheless, Korea’s current interest in the built male body and the remaking of the self should be seen within the context of shifting gender roles: the last two decades have witnessed increased rates of higher education and rising consumer power for females, as well as a legal dismantling of gender discrimination with significant changes in family law. One might compare the earlier mainstreaming of competitive

|

Indeed, female consumers are now clearly a significant media target group, and women’s sexual desire is assumed in the marketing of fantasy and desire through the haptic image of the shirtless torso. Sex scenes in Korean films increasingly foreground the male body. For example, in the remake of The Housemaid referred to earlier, the pregnant wife fellates her husband, and while her body remains covered, his naked body is fully on display as her head covers his genitals. When he has intercourse with the title character, his nude figure (sans penis) serves as the focus while the housemaid’s nudity is minimized: the primarily eroticized part of her body is her back. In such scenes, female sexual longings are equated with a wish to be dominated and to service the object of desire: the exposed male represents phallic power.

Many current films, images, and videos feature the shirtless male body as both the object of narcissistic desire and a sign of individual accomplishment. The Good, the Bad, and the Weird

This glorification of narcissism in images of men preening for themselves has troubling implications for both individual emotional development and gender relations more broadly. The DSM-IV (2005) asserts that essential features of Narcissistic Personality Disorder are an exaggerated sense of self-importance, need for admiration, and lack of empathy.25 Much discourse about the Korean nude torso suggests precisely these traits. A studied ambivalence toward the viewer appears in these images. The men convey the impression that

How Healthy Are Those Legs, Anyway?

To conclude, let us consider briefly, in contrast, a video broadcast on Arirang, Korea’s international public relations cable channel, which became notorious in chastising certain female

The clip consists of an excerpted translation of a piece that appeared on Korea’s network Y-Star in its tabloid entertainment show “Ranking High 5.” The original segment discussed five top actresses and girl group members whose striking facial and upper body beauty is paired with lower halves that in the network’s view do not conform to the current domestic ideal, and thereby suggested that bodies deviating from the prescribed norm were unsightly. The Arirang video went further and infuriated viewers via clumsy inattention to linguistic nuance. In translating kŏn’ganghae poinǔn

The segment also highlights an important contrast in the propagation of these images: while both are coercive, men are largely urged to an additional empowerment through strengthening their physical selves, but women, even extremely attractive ones, find that not meeting extraordinarily exacting standards exposes them to public censure. Furthermore, whereas both six-pack abs and long, slender legs are each outwardly directed as symbols of national attractiveness, lingering patriarchal structures allow nude torsos to convey individual phallic power, whereas feminine beauty, though meant to entice, becomes the property of the national collective. As a member of Super Junior teases SM Entertainment stablemates Girls’ Generation on the boy band’s talk show “Kiss The Radio,” “SNSD can’t get hurt without permission. Their bodies aren’t their own. They’re treasures of the nation.” 26

Although in the last decade Korean citizens have clearly been subjected to accelerating regimes of corporeal discipline with the heavily mediated penetration of self-commodification into daily life, these images of male torsos and female legs ultimately offer a variety of interpretive possibilities. (Perhaps most notably absent here are queer readings, especially given the highly homoerotic nature of much boy band imagery.) We have highlighted how these images contribute to the shaping of everyday practices and ideas around ideal bodies. In

These images undeniably offer visual pleasure for their audiences and in doing so can promote greater openness about sexuality more generally. Nonetheless, the enjoyable play of imagination still takes place within a context of power relations as the terms are primarily set by commercial interests. Even as much recent discussion of women’s images has suggested (an admittedly problematic) empowerment through sexuality, the discourses we analyze above treat distinctions between men and women as a binary opposition rooted in biology, exacerbating differences and allowing them to continue as a basis for arguments that justify gender inequality. The potentially regressive social effects of such images urge a tempering note of caution for any who might rush to celebrate them as an empowering expression of individual self-making.

Stephen Epstein is Associate Professor and the Director of the Asian Studies Programme at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. He has published widely on contemporary Korean society and literature and has translated numerous works of Korean and Indonesian fiction. Recent publications include “The Axis of Vaudeville: Images of North Korea in South Korean Popular Culture” (The Asia-Pacific Journal, link) and Complicated Currents: Media Flows, Soft Power and East Asia (co-edited with Daniel Black and Alison Tokita Monash University Publications). His most recent novel translations are The Long Road by Kim In-suk (MerwinAsia, 2010) and Telegram by Putu Wijaya (Lontar Foundation, 2011). He is currently working on a book tentatively titled Korea and its Neighbors: Popular Media and National Identity in the 21st Century.

Rachael Miyung Joo is an Assistant Professor of American Studies at Middlebury College. Her work investigates the connections between sport, nation, and gender in transnational Korean contexts. Her new project on the sport of golf brings together cultural studies of sport and environment to explore ideas of nature and nation in Korean and Korean American communities. She is the author of Transnational Sport: Gender, Media, and Global Korea published by Duke University Press in 2012.

Recommended Citation: Stephen J. Epstein and Rachael M. Joo, “Multiple Exposures: Korean Bodies and the Transnational Imagination,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 10, Issue 33, No. 1, August 13, 2012.

Notes

1 This article grows out of the meshing of two papers presented at the 2012 Association

2 The increased rise in

3 See this February 2012 post from popular English-language K-pop website allkpop.com for anecdotal evidence about the relationship between

4 Not only are so-called “Korean nose lifts” widely advertised in Vietnam and Thailand, a website for the plastic surgery clinic,SP Cosmetic Surgery based in Bangkok, Thailand, offers “Facial extreme makeover as you’ve seen in Korea.” The site is translated into seven different languages and accepts major credit cards.

5 The clip is available at both here and here.

6 Reproduced with permission from the original source: here. An amusing counterpart to this cartoon may be found at 4:20ff of the YouTube clip how to attract a Korean boyfriend.

7 For a particularly egregious example, see Kang (2010).

8 The presence of Nichkhun, a Thai-American, offers an example of how several K-pop groups are including non-Korean members to appeal to a broader audience. Such international members are equally subjected to, and propagate, the bodily ideas we describe in this paper.

9 “Pretty Boys with Abs” posted on 26

10 Several Korean hip hop groups had members who showed off their torsos prior to Rain, but they never achieved the latter’s iconic status in a domestic or international arena.

11 While the term “chocolate abs” refers primarily to the resemblance of the abdominal muscles to the scored sections of a chocolate bar, a racial subtext invoking black male muscularity appears present, all the more so given that many male K-pop groups draw from the aesthetic choices of African-American hip-hop stars for their fashion sense,

12 Kim (1997) and Spielvogel (2003) have written, respectively, about Korean and Japanese fitness clubs and their connections with local practices of consumption, attitudes toward the body and gender, and economic development.

13 Fabian (1983) refers to this

14 “Who is the Real Midas in Korean Showbiz?”, The ChosunIlbo,

15 Indeed, the bare legs, costuming and choreography of Korean idol groups appear to have, very literally, “engendered” different consumer responses in Japan from the latter’s domestic counterparts. YouTube view count statistics indicates that the popularity of AKB48, Japan’s top idol girl group, remains overwhelmingly domestic and that their music video viewers are males in, respectively, the 45-54, 35-44 and 25-34 age brackets. Although Kim

16 See here.

17 See here; here. The

19 See here.

21 See here.

23 See here.

24 We thank Maud Lavin for drawing this point to our attention.

25 See here.

26 See youtube video here. The remark occurs at 21:30 of the clip.

Bibliography

Chung, Ah-Young. “K-pop Takes European Fans By Storm,” 6

Chung, Suzy. “Hey, Where’s Your Skirt?”, 2012.

Connell, R. W. Masculinities. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005.

Debord, Guy. Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books, 1995.

Dudden, Alexis and Kozo Mizoguchi. “Abe’s Violent Denial: Japan’s Prime Minister and the Comfort Women”, Asia-Pacific Journal, 2007.

Dyer, Richard. ”Don’t Look Now.” Screen 23, no. 3-4 (1982): 67-68.

Epstein, Stephen. “Distant Land, Neighbouring Land: Japan in South Korean Popular Discourse” in Complicated Currents: Media Flows, Soft

Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes It Object. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Holliday,

Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

Joo, Rachael. Transnational Sport: Gender, Media, and Global Korea. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Jung, Sun. Korean Masculinities and Transcultural Consumption: Yonsama, Rain, Oldboy, K-Pop Idols, Transasia Screen Cultures. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

Kang Kyŏng-nok, “Han

Khang, Y. H. and S.C. Yun. “Trends in General and Abdominal Obesity among Korean Adults: Findings from 1998, 2001, 2005, and 2007,” Journal of Korean Medical Science 25:11 (2010): 1582-1588.

Kim, Eun Shil, “Yŏsŏng ǔi kŏn’gang

Kim,

Kim, Hyun Mee. “Feminization of the 2002 World Cup and Women’s Fandom.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5, no. 1 (2004): 42-51.

Kim,

Klein, Alan. Little Big Men: Bodybuilding Subculture and Gender Construction. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1993.

Lee, Robert G. Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999.

Ling, L. H. M. “Sex Machine: Global Hypermasculinity and Images of the Asian Woman in Modernity.” positions: east

Mankekar, Purnima, and Louisa Schein. “Introduction: Mediated Transnationalism and Social Erotics.” Journal of Asian Studies 63, no. 2 (2004): 357-365.

Metz, Christian. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychanalysis and the Cinema. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Moon, Seungsook. “Carving Out Space: Civil Society and the Women’s Movement in South Korea. Journal of Asian Studies. 61, no. 2 (2002): 473-500.

Park, Judy. “The Aesthetic Style of Korean Singers in Japan: A Review of Hallyu from the Perspective of Fashion,” International Journal of Business and Social Sciences 2.19 (2011): 23-34.

Puzar, Aljosa. “Asian Dolls and the Western Gaze: Notes on the Female

Rose, Nikolas. ”The Politics of Life Itself.” Theory, Culture & Society 18 (2001): 1-30.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1978.

Sakamoto, Rumi and Matthew Allen. “Hating ‘The Korean Wave’ Comic Books: A Sign of New Nationalism in Japan,”

Slattery, Luke. “Girls’ Generation are the Seoul Sister of the Korean Wave,” 3

Song, Jesook. South Koreans in the Debt Crisis: The Creation of a Neoliberal Welfare Society. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

Spielvogel, Laura. Working out in Japan: Shaping the Female Body in Tokyo Fitness Clubs. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Williams, Linda. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure and the Frenzy of the Visible. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989.

Yamanaka, Chie. “The Korean Wave and Anti-Korean Discourse in Japan: A Genealogy of Popular Representations of Korea” in Complicated Currents: Media Flows, Soft