Becoming “Chinese”—But What “Chinese”?—in Southeast Asia

Caroline S. Hau

Over the past three decades, it has become “chic”1 to be “Chinese” or to showcase one’s “Chinese” connections in Southeast Asia. Leaders ranging from President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino of the Philippines to King Bhumibol Adulyadej, Prime Minister Kukrit Pramoj, and Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra of Thailand to President Abdurrahman Wahid of Indonesia and Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi of Malaysia have proclaimed their Chinese ancestry. Since 2000, Chinese New Year (Imlek) has been officially celebrated in Indonesia, after decades of legal restrictions governing access to economic opportunities and Chinese-language education, use of Chinese names, and public observance of Chinese customs and ceremonies.

Beyond elite and official pronouncements, popular culture has been instrumental in disseminating positive images of “Chinese” and “Chineseness.” In Thailand, for example, the highly rated TV drama Lod Lai Mangkorn (Through the Dragon Design, 1992), adapted from the novelistic saga of a penurious Chinese immigrant turned multimillionaire and aired on the state-run channel, has claimed the entrepreneurial virtues of “diligence, patience, self-reliance, discipline, determination, parsimony, self-denial, business acumen, friendship, family ties, honesty, shrewdness, [and] modesty” as “Chinese” and worthy of emulation.2 The critical acclaim and commercial success of another rags-to-riches epic from the Philippines, Mano Po (I Kiss Your Hand, 2002), spawned five eponymous “sequels.”3 In Indonesia, the biopic Gie (2005) sets out to challenge the stereotype of the “Chinese” as “material man,” communist, and dictator’s crony by focusing on legendary activist Soe Hok Gie. In Malaysia, the award-winning Sepet (Slit-eyes, 2005) reflects on the vicissitudes of official multiracialism through the story of a well-to-do Malay girl whose passion for East Asian pop culture leads her to befriend, and fall in love with, a working-class Chinese boy who sells pirated Video Compact Discs.

The term “re-Sinicization” (or “resinification”) has been applied to the revival of hitherto devalued, occluded, or repressed “Chineseness,” and more generally to the phenomenon of increasing visibility, acceptability, and self-assertiveness of ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.4 The phenomenon of “re-Sinicization” marks a significant departure from an era in which “China” served as a model for the localization of socialism and propagation of socialist revolution in parts of Southeast Asia in the 1950s and 1960s, and Southeast Asian “Chinese” were viewed and treated as economically dominant, culturally different, and politically disloyal Others to be “de-Sinicized” through nation-building discourses and policies.

For want of a better word, the term “re-Sinicization” has served as an expedient signpost for the variegated manifestations and revaluations of such Chineseness. Its use does not simply affirm the conventional understanding of Sinicization as a unilinear, unidirectional, and foreordained process of “becoming Chinese” that radiates (or is expected to increasingly radiate) outward from mainland China.5 Since the “Sinosphere”6 was inhabited by different “Chinas” at different times in history, the process of modern “Sinicization” cannot be analyzed in terms of a self-contained, autochthonous “China” or “Chinese” world, let alone “Chinese” identity. These “Chinas” were themselves products of hybridization7 and acculturation born of their intimate and sometimes contentious cultural, economic, and military contacts with populations across their western continental frontiers, most notably Mongols and Manchus, and with Southern Asia (India and Southeast Asia) across their southern frontiers.8 This Sinosphere began to break down in the mid-nineteenth century. In their modern articulations, “China,” “Chinese,” and “Chineseness” are relational terms that, over the past century and a half, point to a history of conceptual disjunctions and distinctive patterns of hybridization arising from the hegemonic challenges that the maritime powers of the “West” posed to the Sinocentric world. And in that world, social, economic, cultural, and intellectual interactions among many different sites were intense and largely enabled by the regional and global flows and movements of capital, people, goods, technologies, and ideas within and beyond the contexts of British and, later, American hegemony in East and Southeast Asia.

Without discounting China’s contribution to modern world-making9 over the past century and a half, this article complicates the idea of “Sinicization” as a mainland state-centered and -driven process of remaking the world (and the ethnic Chinese outside its borders) in its own image. Instead, it proposes to understand “Sinicization” as a complex, historically contingent process entailing not just multiple actors and practices, but equally important, multiple sites from which they, over time, have created, reinvented, and transformed received meanings associated with “China,” “Chinese,” “Chineseness.” Sinicization cannot be studied apart from the related concepts of re-Sinicization and de-Sinicization; taken together, they can best be understood as a congeries of pressures and possibilities, constraints and opportunities for “becoming-Chinese” that are subject to centripetal and centrifugal forces – as Wang Gungwu10 has noted for the cultural context of territorialization and de/reterritorialization.11 One crucial implication is that in this process of recalibration no single institution or agent, not even the putative superpower People’s Republic of China, has so far been able to definitively claim authority as the final cultural arbiter of what constitutes “Chinese” and “Chineseness” or even, for that matter, “China.”

Conceptual Disjunctions

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, Qing China confronted a hegemonic challenge, not from across its continental borders to the west, but from the maritime world to its east. A far-reaching consequence of this period is that the genesis of the modern term Zhongguo = China and related signifiers such as Zhonghua = “Chinese” and “Chineseness” (a term for which there is no exact Chinese-language equivalent) is characterized by reterritorializing as well as deterritorializing impulses that arise from conceptual disjunctions in the Zhongguo = China equation. Rising nationalist sentiments made “Chinese/ness” an issue of paramount importance for “China” in its multiple discursive, territorial, and regime manifestations, and for the so-called “Chinese” in Southeast Asia (the principal region of immigration from the mainland) and their host states and societies. This created multiple disjunctions between territory, nation, state, culture, and civilization – key concepts in the study of modern politics – in the signifiers “China” and “Chinese/ness.”

This is not to argue that the concepts of territory, nation, state, culture and civilization lack any referent; on the contrary, modern Chinese history is an account of the prodigious time and energy expended, not to mention the blood-sweat-tears spilled, on determining, fixing, or challenging and changing the proper cultural, political, territorial, and civilizational referents of “China”.12 The fact that “China” was and continues to be a floating signifier13 – that is, its referents are variable, sometimes indeterminate and unspecifiable – does not in any way suggest that “China” is purely a discursive construction; it only means that there is an irreducibly discursive dimension to the relationship of ethnic-“Chinese” with “China.” Taxonomic studies of ethnic “Chinese” political loyalty and orientations, and multiple manifestations of “Chineseness,” can best be understood as attempts at making sense of the multiplicity of assertions, commitments, persuasions, declarations, and expressions generated by the floating signifier “China.” They highlight the productive potential of the signifier “China” to be made to mean and do something, conditioning practices and claims made in the name of “China” and “Chinese.”

Between the late nineteenth and the mid-twentieth century, there was a political disjunction as various entities and movements at various times – from late Qing provincial and central authorities, to reformers such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, to revolutionaries such as Sun Yat-sen, and on to warlords, the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party – reached out to the “Chinese” in “China” as well as Nanyang (Southeast Asia) and elsewhere.14 Motivated by imperatives of mobilizing human, financial, and affective resources, each of these appeals to the “Chinese” accomplished two tasks. It drew on or tapped different wellsprings of attachment to and identification with native place(s), ancestry, and origins; and it articulated competing political visions of community, people, nation, and state. Political disjunction meant that there was no easy or necessary fit between nation and state.15 Different political movements, whose activities and mobilization sometimes took place outside of the territory of “China,” targeted specific “Chinese” localities and communities and competed to capture the state and remake society in the image of their visions of the nation. “China”-driven Sinicization thus represents various attempts on the part of different “Chinese” regimes and actors to propound their notions of Chineseness and mobilize “Chinese” capital, resources, labor, and specific talents/skills for economic, political, and cultural objectives inside and outside the territorial boundaries of “China.”

Such attempts to reterritorialize the “Chinese” in Southeast Asia were in some ways successful. They helped to create a new political, and more importantly, mobilizable entity called the huaqiao, a term that came into general use at the end of the nineteenth century but acquired its territorializing connotations only at the beginning of the twentieth.16 But these efforts often came up short against competing deterritorializations and reterritorializations of “Chinese” and “Chineseness” that had taken place for at least three centuries in the colonial states of Southeast Asia – especially the Spanish Philippines, Dutch East Indies, British Malaya, and French Indochina. Their regimes promoted, cemented, and reinvented specific forms of “Chinese” identification and identities while curtailing or repressing others.17

The “Chinese” had an important role in the Western colonies established in Southeast Asia. They were crucial agents and mediators in Spanish, British, Dutch and French attempts to insert themselves into, to regulate and rechannel, the flows and networks of the regional maritime trade between China and its neighbors. Moreover, colonial states adopted different policies toward the “Chinese” as part of the divide-and-conquer logic of governing their resident populations. These policies had different consequences.

In the early years of colonial rule, for example, the Spanish in the Philippines relied on the category of mestizo (mixed blood) to administratively distinguish the Philippine-born offspring of sangley (“Chinese”)-native unions from their (China-born and Christian converted) sangley fathers. Their access to their fathers’ capital and their socialization in their mothers’ native cultures made the mestizos among the most socially mobile and hybrid strata of the colonial population. Acquiring economic clout by taking over the hitherto sangley-dominated trade during the prohibition of sangley immigration between 1766 to 1850, these mestizos were instrumental in appropriating the term “Filipino” (a term originally denoting Spanish creoles) and giving it a national(ist) signification. But while this resignification promoted hybridity as a nationalist ideal, it effectively occluded these mestizos’ “Chinese” ancestry and connections and codified the “Chinese” as Filipino nationalism’s Other. This double move helped to promote identification with “white” Europe and America.

Thailand exemplifies a different historical trajectory: at the turn of the twentieth century, cultural notions of Chineseness had been far less important in the eyes of the Chakri kings than the political fealty and economic utility of these “subjects” to the monarchical state. That preeminent symbol of Chineseness, the pigtail, as Kasian Tejapira18 has argued, at first signified identification with the Qing empire. Later transformed into a marker of cultural nativism among the jeks, it was mainly viewed by the Thai state as a signifier for a specific administrative category, a specific tax value, and opium addiction. Only later, when Chinese republicanism came to be seen as a political threat to the state, did the Thai monarch Vajiravudh (Rama VI) actively propound a racial conception of Thai-ness that was opposed to Chineseness.19 New urban middle classes emerged out of “state-centralized and supervised national education system, together with the rapid, state-planned, capitalist economic development”20 under Sarit Thanarat in 1961, and included a sizeable number of lookjin who were born and raised in Thailand, worked in the most advanced sectors of both economy and culture, possessed economic and consumer clout, but remained outside the state. These lookjin became politicized and were active in both militant and peaceful social movements, including the October 14, 1973 uprising, the communist armed struggle, and the uprising of the May Democratic Movement of 1992. The end of the Thai Communist insurgency (which, like its counterparts in the Philippines and Malaya, had strong links with Communist China), coupled with market reforms in China, and Deng Xiaoping’s visit to Thailand served to delink “Chineseness” from its associations with political radicalism and nationalist Other.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, intermarriages between Chinese and natives had produced a stable “third culture” of peranakan and baba, whom Dutch and British colonial policies classified as “Chinese” and whom the colonial systems of social hierarchy, privileges and incentives discouraged from assimilating into native society. Fresh waves of migration from China in the late nineteenth century created pressures to Sinicize on the part of the baba. As their political awakening preceded that of the successful anti-Manchu revolution in China, the peranakan worked through their modern identification as “Chinese” by means of active participation in Indies politics.21 In the 1950s up to the mid-1960s (particularly 1963-1965), China and Indonesia under Soekarno’s Guided Democracy enjoyed close relations which led to the coining of the term “Pyongyang-Beijing-Jakarta Axis”22. Suharto, however, viewed Communist China as the major foreign threat to his regime, and enacted a series of regulations to place ethnic Chinese of both Chinese and Indonesian citizenship under surveillance and to forcibly integrate the “Chinese.”

The most salient feature of the colonial Southeast Asian state’s treatment of the “Chinese” is the association of “Chinese” with commerce and capital, an identification that originated in the context of maritime trade and colonial economic enterprise but glosses over the existence of sizeable communities of Chinese laborers, especially in Malaysia. (The Qing and Nationalist states may have also reinforced this historical conflation of ethnicity and commerce/capital by treating the huaqiao primarily as sources of financial “contributions” to underwrite state-led projects and undertakings and as sources of remittances to help shore up the economy in China.) Such identification effectively conditioned the socialization of “Chinese” migrants as “material men” who played an indispensable role in the colonial and later post-colonial economies. Reproduced and perpetuated through social relations of production that were characteristic of “Chinese” enterprise in the region,23 this socialization enabled the “Chinese” to take advantage of the opportunities that were available in the colonial states and economies. But it also rendered them vulnerable to nationalist opprobrium that stigmatized “alien Chinese” as economically dominant and politically unreliable. “Chinese” participation in the national economies of Southeast Asia is significant and visible enough to lend anecdotal credence to the myth of “Chinese” economic dominance. This myth, however, is based on popularly disseminated statistics which, as Rupert Hodder shows, are often problematic in their calculations, if not their assumptions about who counts as “Chinese” and whether ethnicity is an issue: Chinese constitute 10 percent of the population of Thailand but allegedly command an 80 percent share of the country’s market capital; in Indonesia, the share of market capital of a mere 3.5 percent of the population is supposed to be 75 percent; in Vietnam, 3 percent of the population is responsible for 50 percent of Ho Chi Minh’s market activity; and in Malaysia, they constitute about one third of the population, but have a 60- to 70 percent share of the country’s market capital.24 The visibility and economic prominence of the “Chinese” made them ready targets of nationalist policies aimed at disentangling the link between ethnicity and class through domestication of “cultural” differences (via assimilation and integration) and redistribution of wealth.

Even though a combination of generational change and global/regional economic development has in recent decades produced sizeable urban professional middle classes that include not only “Chinese” but also non-Chinese Southeast Asians, economic regionalization has further cemented this identification of “Chinese” with capital. The crucial difference is that in the throes of economic and social transformation, post-colonial states and societies have generally re-valued the identification of Chinese with capital in positive terms. This continuing identification of Chinese with capital is the source of “Chinese” assertive self-empowerment but also of continuing vulnerability to popular-nationalist ressentiment in contemporary Southeast Asia. Oscillating between these two poles, popular media portray Chinese as “heroes” of regional economic development and “villains” in times of economic crisis (and easy targets of violence, as in the case of Chinese Indonesians during the Asian crisis of 1997-8).

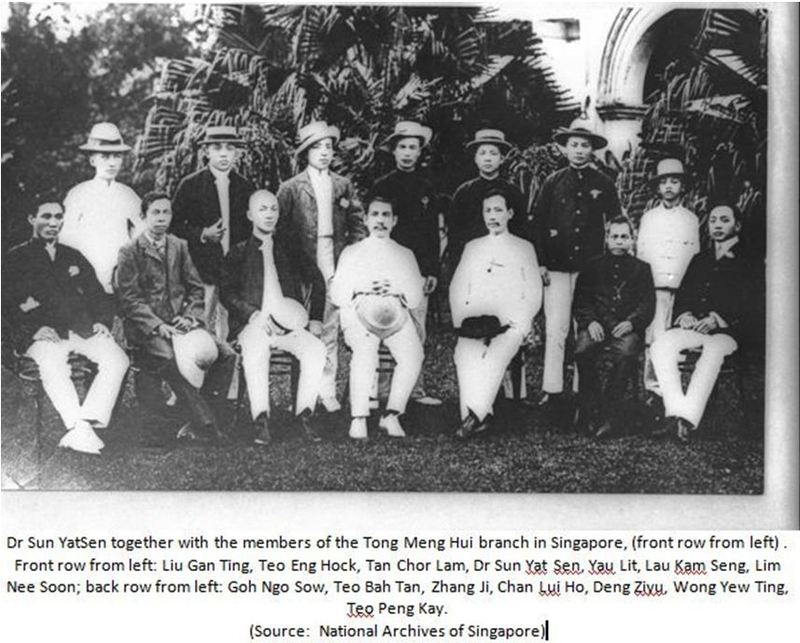

What constitutes “Chinese” culture in the modernist sense of the term is continually enriched by the development of hybrid “Chinese” cultures that owe a great deal to the local histories of settlement and cultural contacts in social spaces both within and outside the purview of the mainland state. The politicized huaqiao nationalism among “Chinese” immigrants and their descendants in Southeast Asia and elsewhere was a “peripheral” sort that was dependent and conditional on developments and contestations on the mainland. Physical and psychological distance from China gave it leeway to define its various “Chinese” cultures according to the pressures operating and opportunities open in the countries of residence.25 At the same time, huaqiao activities had an impact on the mainland. Overseas Chinese support for the nationalist movement led Sun Yat-sen to call the huaqiao the “mother of revolution” (geming zhi mu).

|

Southeast Asian Chinese provided substantial financial support for “national salvation” activities against the Japanese in the 1930s and 1940s. Moreover, in the decades since the re-opening of China, in deeply interactive processes, investment by ethnic Chinese from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, America and elsewhere has been crucial to the economic modernization of the mainland.26 In the past decade, mainland China has emerged as the dominant trading partner of countries in Southeast Asia and East Asia more generally. It is Malaysia’s biggest trading partner, Thailand’s second largest trading partner, and the Philippines’ third largest trading partner, with ASEAN being projected to become China’s largest trading partner by 2015.27 China’s deepening economic integration through trade and investment in the region we now call East Asia and its Pacific partners (notably America and Canada) is also crucially mediated by ethnic Chinese living and working in and across the region.

To complicate the issue, during the first half of the twentieth century the mainland “Chinese” state was not unitary, weakened as it had been during the late Qing and the Republican years. In the twentieth century, the threat of dismemberment and secession loomed large as China was subject to decentralized rule by competing warlords, occupation by imperial Japan, and a civil war between the KMT and CCP. The enduring myth of historical continuity that rests on the ideal of a unitary state28 belies the reality of fragmentation of power and authority, with the state(s) serving as object(s) of intense competition among different forces. Another disjunction arises from the modern state’s fraught and contested inheritance of the territorial boundaries established by the Qing (with precedents in boundaries set by the Mongols and claimed by the Ming). “China”’s internal division was not the only significant disjunction. Equally important was the physical fragmentation around the edges of the Qing empire, particularly the loss of Hong Kong to the British and Taiwan to the Japanese. These geopolitical “splits” were to have crucial consequences during the Cold War era, when the mainland was “closed” to the American-dominated “Free Asia,” and Taiwan and Hong Kong emerged as interlinked (but not necessarily overlapping) purveyors, respectively, of state-authorized and market-driven “Chinese” culture and “Chineseness” through the circulation of media and popular culture. In the post-Cold War era, the status of Taiwan remains a flashpoint as mainland China’s integration into (and increasing importance in) the “East Asian” trade system has proceeded alongside its continuing exclusion from the hub-and-spokes security framework.

On the international front, Taiwan and Mainland China competed, with varying degrees of success, for the attention and support (if not loyalty) of overseas Chinese during the Cold War era.29 (This does not mean, however, that these geopolitical sites of Chinese representations and contestations were totally discrete and mutually exclusive.) The opening of China after 1978 has seen further deterritorialization through large-scale migration from China as well as re-migration of ethnic Chinese from Northeast and Southeast Asia to mainly English-speaking countries of America and the Commonwealth of Nations. Simultaneously, reterritorializations have occurred as the crisis of faith engendered by the retreat of socialism and socialist thought created a vacuum filled by versions of nationalist and Confucianist discourses propounded by diverse states, markets, communities, and individuals inside and outside China.30 Various actors sought to fill the void through literature, mass media such as newspapers, films, and television shows, and cybermedia, as well as regime sponsorships of Confucianism, Taiwanese cultural nationalism, and other undertakings.

“Sino-Japanese-English” Hybridization in the Age of Collective Imperialism

Conceptual disjunction is not the only characteristic feature of the modern term “China” and its attendant signifiers. A specific pattern of hybridization has also been crucial to the emergence of modern “China” and its culture and politics. It has long been accepted that cultural inflows traditionally entered imperial China mainly through continental (particularly Inner) Asia and through the overland routes that brought Buddhism from India. Several times in its history, “China” was ruled by non-Han: the Mongols, who incorporated China into the first world-empire in history; and the Manchus, who presided over a multi-ethnic empire and cemented their legitimacy among the Han Chinese by selectively Sinicizing themselves (without, however, completely erasing their ethnic identification as Manchus) and acting as principal sponsors of state-propagated Confucianism.31

Rather than its lack of interest in exporting its institutions, social practices, and values,32 limits to the reach and might of the mainland state were instrumental in delineating its relations with neighbors to the east.33 Its relations with Korea and Vietnam, with whom it shared borders, were historically organized in terms of a China-centered tributary system, periodically backed by military power, allowing for a flexible range of appropriations of – and acculturation to – things Chinese by neighboring states.34 Even as Vietnam closely modeled its institutions and practices after China, it actively engaged in a form of appropriation that drew on “civilizational” notions shared among different polities in the East Asian region while abstracting the term for China from its geographical reference to the mainland.35 This abstraction enabled the Vietnamese court and scholar-officials to enthusiastically adopt Confucian institutions and norms while simultaneously resisting political domination by the mainland state.36 Farther removed from China’s reach, some polities in the region, such as Malaka and Butuan, sent tributary missions to China to secure economic benefits and accrue social prestige, without adopting wholesale Chinese institutions and social practices.

The hybridization that arose during the maritime period from the collision between China and the “West” entailed a different cultural politics. The flows of people and modes of transmission of new political and cultural ideas – as well as the new conceptions of community that entered and circulated in China from the West – ran through pathways and networks created in the East. Consequently, the making of “China” in the modern period is crucially mediated by two non-Chinese communicative spheres, Japanese and English (both British and American), which were created by the regional system in the East in which Britain, Japan, and the US competed for dominance. Between the late nineteenth century and the 1930s, the formation of an East-based system of collective imperialism linked the territories and economies of China, Japan, and Southeast Asia, providing the bridges and avenues through which peoples, commodities, languages, and ideas moved into China.

This pattern of flows to, through, and from China is nested in a specific regional structure of power and wealth. Although western powers dominated the international order that provided the institutional framework for “forced free trade” in the region, the economic impact of the West on China was confined mainly to the littoral regions.37 It was intra-Asian trade, mediated by western collective imperialism, that penetrated China’s hinterlands and connected China to the world market. In this sense, the impact of the West was principally mediated through intra-Asian regional links and connections among China, Japan, and the various colonies in Southeast Asia. Chinese merchants and the development of colonial economies, underpinned in part by Chinese labor, played a crucial role in this connecting process.38 This regional system, rather than the “West” per se, played a central part in China- and world-making. In its cultural matrix, Japanese was an important linguistic mode of transmission of western concepts, while English served as the de facto regional and commercial lingua franca.

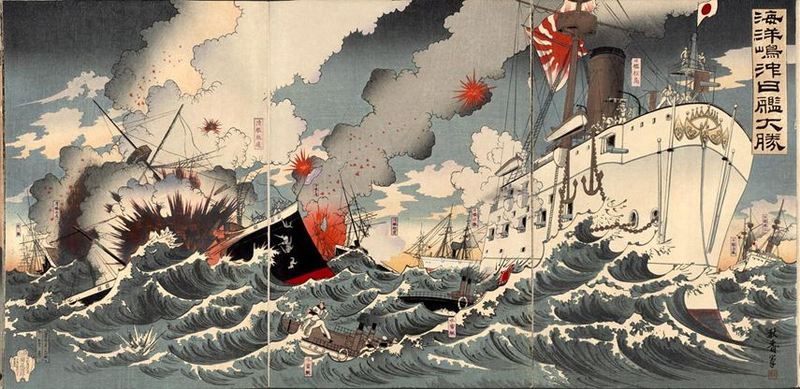

The relationship between China and the so-called “West” was crucially mediated by the reconfigured relationship between China and Japan. Japan’s victory over Qing China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5 was a spectacular reversal of traditional China-to-Japan unidirectional cultural flows.

|

|

From the final years of the nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth, the number of Chinese students who received their education in Japan surpassed the combined numbers of their compatriots in Europe and America.39 These Chinese ryugakusei/liuxuesheng were key agents in the “translingual practices” (to use Lydia Liu’s term) that decisively shaped the very terms by which, for intellectual and political purposes, the “West” was discursively constructed and deployed in a China-West binary.40 Through these practices, basic vocabulary such as politics (zhengzhi), economics (jingji), and culture (wenhua) entered the Chinese lexicon and circulated in China through “Sino-Japanese-English” translations in which not only Japan-educated Chinese and Japanese, but also western missionaries, played important roles.41 More than half of the loan words in the Chinese language are from Japanese;42 one Chinese scholar has gone so far as to argue that 70 per cent of the modern terms regularly used in the social sciences and humanities are imported from Japanese.43 Some of these Japanese terms were neologisms first coined by western missionaries and subsequently re-imported to China via Japanese texts. Others were either neologisms rendered in kanji (Chinese character) form by the Japanese, or old classical kanji/Chinese terms that were assigned new and modern meanings by the Japanese, and then re-imported into China.

An early political form taken by these translingual practices was Asianism, for which Tokyo/Yokohama served as the main hub, with smaller hubs in San Francisco, Singapore, Siam, and Hong Kong. Here, a kind of Sino-Japanese kanji/hanyu communicative sphere helped create a network that linked, at different times, personalities such as Kim Okgyun of Korea, Inukai Tsuyoshi and Miyazaki Toten of Japan, Sun-Yat-sen of China, and Phan Boi Chau of Vietnam.44 But it is also instructive to note that English became the second lingua franca of this Asianist network, connecting Suehiro Tetcho to Jose Rizal, and Sun Yat-sen and An Kyong-su to Mariano Ponce. Sun Yat-sen communicated with his Japanese friends and allies through Chinese (often in brush conversations or bitan/hitsudan) as well as English. He switched completely to English when communicating with Filipino nationalist Mariano Ponce, as did Japanese activists like Suehiro Tetcho and Miyazaki Toten.

In fact, along with his connections with Japan and Korea through the medium of written Chinese, Sun also exemplifies a specific kind of “modern Chinese” that first emerged in port cities such as Shanghai, Tientsin, Canton, and Amoy, as well as sites of Chinese immigration in Southeast Asia and America. The “Anglo-Chinese” (to use a term by Takashi Shiraishi45) were part of the British formal and commercial empire in the region in the nineteenth century.46 In Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, Anglo-Chinese – who, along with a smaller number of their Japanese counterparts, were often educated by Christian missionaries – staffed the bureaucracy and constituted the nascent middle classes of professionals (such as doctors) and scions of Chinese merchants. Educated in both Chinese and English and sometimes only in English, and interpellated as “Chinese” by the colonial policies of their respective domiciles, these Anglo-Chinese were proficient in local and colonial languages such as Cantonese, Hokkien, Malay, Javanese, Tagalog, Dutch, Portuguese, and French. Their multilingualism (and especially their proficiency in English, the commercial regional lingua franca) gave them the cultural resources to move across social and linguistic hierarchies in their polyglot colonial societies and beyond.47

These multicultural/hybrid Chinese include the Penang (Malaysia)-born Lim Boon Keng (Lin Wenqing, 1869-1957), a doctor by profession who was educated in Edinburgh. He was an associate of Sun Yat-sen and later president of Xiamen (Amoy) University, and a key figure in the propagation of Confucianism in Singapore, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies.

Spurred by his exposure to English texts on China and Chinese classics, and the colonial dispensation that labeled him “Chinese,” his attempt at creating a “modern Chinese identity” entailed the elevation of Confucianism to a national as well as a universal philosophy and religion comparable to, and on a par with, Christianity.48 His idea of an emergent Chineseness was not rooted in outward or physical signs of Chineseness (for example, costume or hairstyle), but rather in a personal code or morality that prepared the Chinese for progress. At the same time, as Wang Gungwu has pointed out, Lim’s advocacy of Confucian education was complemented by his support for a modern curriculum that included the teaching of science. Famously delivered in English at his presidential address at Xiamen University49 on 3 October 1926, his vision of revivified Confucian teachings for the present time offered a distinctive platform for modernization in China. Despite differing sharply from the anti-tradition Chinese modernity envisioned by the Sino-Japanese hybrid Lu Xun, it was in all respects as modern as Lu’s.50

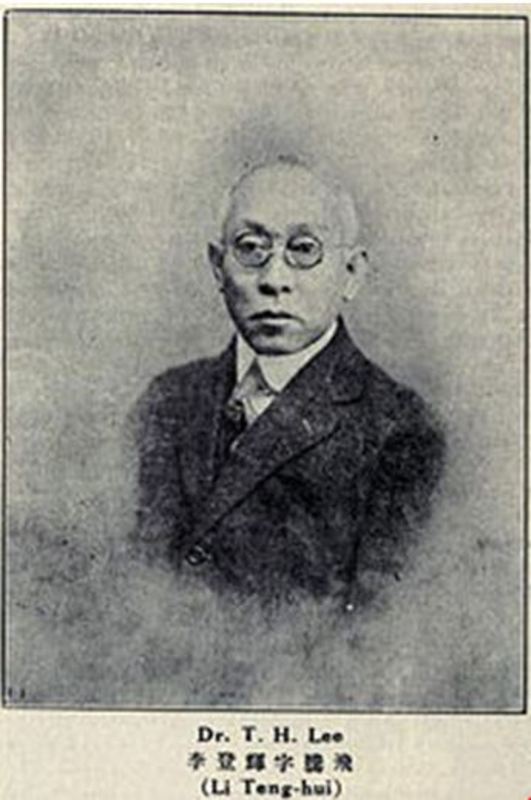

Two other exemplary Anglo-Chinese from opposite ends of the political spectrum are conservative Ku Hung-ming (Gu Hongming, 1857-1928) and May 4th activist Lee Teng Hwee (Li Denghui, 1872-1947).

Like Lim Boon Keng, Ku Hung-ming was born in Penang and educated in Edinburgh, but he also studied in Leipzig and Paris. Fluent in English, Chinese, French, and German, among other languages, he translated Confucian and other classic texts into English, worked for the Qing government, and advocated a form of orthodox Confucianism that, counterposed to European civilization, proved to be unpopular even among Chinese.51 Lee was born near Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) and educated at the Anglo-Chinese School in Singapore and Yale University in the US. He founded the Yale Institute, taught at the Tiong Hwa Hwee Koan in Batavia, and later became the first president of Fudan University in Shanghai.52

The impact of political Asianism was limited and eventually curtailed by Japanese imperialism. It spurred the development of Chinese nationalism by providing Chinese nationalists with an identifiable enemy against which the Chinese people could be mobilized. Sino-Japanese-English translingual practices arguably had a far wider influence especially on Chinese culture, politics, and military organization.53 Such translingual practices transformed Chinese institutions and practices, bearing out the discursive and dispositional aspects of Sinicization. Their political impact is readily apparent in the crucial role they played in the introduction of socialist thought into China, via translation from Japanese. Ishikawa Yoshihiko’s54 study reveals that, between 1919 and 1921, 13 out of 18 Chinese translations of texts by Marx and Engels, as well as other Marxist figures – including The Communist Manifesto – were based on Japanese translations. Writings by Japanese anarchists and Marxists such as Kotoku Shusui, Osugi Sakae, and Kawakami Hajime also were read in China, Korea, and Vietnam, and influenced the development of socialism in these countries.55 Where political surveillance of and crackdowns against Bolshevism restricted its transmission from Japan to China, Bolshevist thought, including its visual imagery, entered China via translations from English (many of them published in America) through the treaty port of Shanghai. Shanghai itself is a spatial representation of this Sino-Japanese-English hybridization: the British provided the policing and administration; the Japanese constituted the largest foreign contingent; and the gray zones created by the administratively segmented International Settlements enabled nationalists and communists from Asia and beyond to flourish, allowing figures such as Tan Malaka, Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh), Hilaire Noulens, and Agnes Smedley (who communicated with each other in English, a lingua franca of the Comintern) to meet, mingle, and organize their respective political projects in the name of the nation and international solidarity.

Beyond mainland China, the Sino-Japanese-English cultural nexus was an enabling ground not only for the revolutionary movement in the Philippines, but also for the political awakening of the Indies Chinese, whose activities would provide models and inspiration for Indonesian nationalist activism. Tiong Hwa Hwee Koan, the first social and educational association established in 1900, recruited staff from Chinese ryugakusei in Japan to teach not only Chinese but also English.56 Its textbooks, which were published in Japan and later in Shanghai, had originally been designed for use by Chinese students in a Yokohama school run by a Yokohama Chinese; that school’s opening had been graced by Sun Yat-sen and Inukai Tsuyoshi.57 The Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer would memorialize the Chinese influence on Indonesian nationalism through the revolutionary Khouw Ah Soe – a graduate of an English-language high school in Shanghai. Although Soe does not publicly acknowledge this, he had in fact lived for some years in Japan before being sent to do political organizing among the Indies Chinese. In Anak Semua Bangsa (Child of All Nations, 1980),58 the protagonist Minke learns from Soe about anticolonial struggles in the Philippines and China. In a little over one generation, this political awakening and educational trend would produce Anglo-Chinese Indonesians such as Njoo Cheong Seng (1902-62), whose popular Gagaklodra series of martial-arts fiction features an eponymous half-Chinese, half-Javanese protagonist. Njoo typified a new generation of Indonesian Chinese who were comfortable not only with Indonesian (and Dutch), but learned some English as well. In imagining an Indonesian nationalism that was not incompatible with Chinese patriotism, he drew inspiration from both British and American literary traditions and popular cultures (especially American comics and Hollywood films).59

|

Thailand offers another interesting case study, of a different path of transmission of radical nationalism through the regional circulation of people and transmission of ideas. Communism came to Thailand not from the West, but via the East through Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants. Considered part of the Communist Party of Malaya, Thailand’s communist party would in turn make Siam a strategic base and hub for the establishment of communist cells in Laos and Cambodia by Ho Chi Minh.60 Although gifted Sino-Thais were able to obtain their education in England and, less frequently, in France, English education at the time was limited to Thai aristocrats, bureaucrats, and the nascent middle class. Sino-Thais received their education in China or in nearby Straits Chinese schools. The bilingual Thai-born lookjin, who were instrumental in translating socialist texts into Thai, bonded with their Thai counterparts in prison. During the American-led Cold War period, they achieved proficiency in English, enabling them to work on translation along with Thai radicals. This pattern of increasing proficiency in the language of British and later American regional domination would be of great consequence in the post-Cold War period.

The Rise of the Anglo-Chinese under American Hegemony

Japan’s primacy as a translingual hub was undermined by Japanese imperialism and its failed attempt to establish hegemony in the region. After its defeat, Japan was incorporated into the American-led “Free Asia” through a hub-and-spokes regional security system (anchored in the US-Japan alliance and bilateral treaties between the US and its Southeast Asian allies) and a triangular trade system involving the US, Japan, and the rest of “Free Asia” that officially excluded Communist China.61

Of equal import was the fact that for the first quarter century of this new regional arrangement, ethnic Chinese migrants faced a great deal of pressure from postcolonial nation-states in Southeast Asia to de-Sinicize. This pressure reached its apotheosis in the anti-Chinese discrimination practiced in Indonesia, which actively sought to erase all visible (and auditory) signs of Chineseness. Along with the postcolonial states in Malaysia and the Philippines, Indonesia aimed to regulate if not restrict the economic activities of ethnic Chinese through economic nationalism and affirmative-action programs favoring bumiputera (“sons of the soil”). While these de-Sinicizing policies and the absence of direct contact with mainland China succeeded in nationalizing the Chinese minority, erasing Chineseness by granting the Chinese Indonesian a form of second-class citizenship ironically reinforced and perpetuated the treatment of the ethnic Chinese as “alien” nationals.62 The situation of the Chinese in the Philippines, however, shows how changing diplomatic and economic imperatives led to shifts in state policies, as the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the Philippines and China in 1975 paved the way for the mass granting of Filipino citizenship to large numbers of Chinese. The hitherto alien Chinese, through college education, were drawn into closer and more frequent social contact with Filipinos and came to identify themselves as “Filipino,” thus facilitating their incorporation into both the national imaginary and the body politic.

State-driven attempts at de-Sinicizing the Chinese and more recent market-driven re-Sinicization of the Chinese occurred with novel forms of hybridization. Anglophone education in the region and abroad and the acquisition of linguistic proficiency in English (or more accurately, englishes) became a widespread phenomenon that reached beyond the elites and professionals and scions of rich merchants of the earlier period to encompass the growing middle classes and urban populations. This hybridization also involves nationalization that incorporates elements and languages of Southeast Asia’s indigenous cultures. The product and agent of this process is the “Anglo-Chinese” (and, in the case of the Southeast Asian Chinese, “Anglo-Chinese-Indonesian,” and so on). The term “Anglo-Chinese” was originally applied to schools (sometimes western missionary-run) where sons (and later daughters) of ethnic-Chinese businessmen received the kind of education that prepared them for business and/or professional careers. A version of the Confucian classics was taught in Chinese (Guoyu), alongside English and practical subjects such as accounting. Such “hybrid” schools were established in the Nanyang territories (mainly in the British colonies of Singapore and Malaya, but also in Indonesia and the Philippines), and in the port cities of Hong Kong, Tientsin, Canton, Amoy, and Shanghai; some of their graduates went on to pursue higher education either in China or, more commonly, in England and America.

A term that originated in the maritime-Asian world under British hegemony can thus be fruitfully applied to the contemporary regional context of the East Asian hybridization of Chinese under American hegemony. The crucial linguistic continuity from British to American English marked the transition from British to American hegemony and promoted the use of English as a regional and commercial lingua franca. What followed was the widespread dissemination of Hollywood films and, eventually, the Americanization of bureaucratic elites and professional middle-classes and their worldviews. Like their forefathers in this region, the Anglo-Chinese tend to have the following characteristics: they are at least bilingual (with English as one of their major languages); they received a western-style education (which normally includes secondary, tertiary or graduate education in America or Britain);63 they have some grounding in the school systems in their respective countries and intend to educate their children in the same way; they are well-versed in “international” (mainly Anglo-American) business norms and values; and they have relied on their hybrid skills (whether linguistic or cultural) and connections to enter business and work as entrepreneurs and professionals. One can also speak of comparable processes of Anglo-Japanization of Japanese, Anglo-Koreanization of Koreans, Anglo-Sinicization of Taiwanese, and comparable phenomena among segments of Southeast Asian middle and upper classes.

Far removed from the context of anti-imperialist nationalism that was the engine of “China”-driven Sinicization in the first half of the twentieth century, “re-Sinicization” is today more a component of, rather than an alternative to, ethnic Chinese Anglo-Sinicization. Now primarily market-driven, it is propelled as much by economic incentives for learning Mandarin Chinese and seeking jobs in a rapidly growing China and East Asian region as by the desire to learn about “Chinese” culture in a more hospitable political environment. Wang Gungwu64 calls this the new huaqiao syndrome, in which the mainland Chinese nation state is an increasingly important, but by no means the only, source of economic opportunities and cultural identification and validation. This process may entail a form of Sinicization that involves the Mandarinization of erstwhile provincialized/localized huaqiao identities, as the pressures and incentives among Anglo-Chinese to learn putonghua (as well as the simplified Chinese script) increase with China’s economic rise. But it is not likely to happen at the expense of ongoing Anglo-hybridization, and may very well complement it. Moreover, the process of selective Anglo-hybridization involves not only ethnic Chinese, but also non-Chinese Southeast Asian elites and middle classes. It prepares the ground for the creation of an encompassing and inclusive cultural frame of reference and communicative meeting ground for interaction among the Southeast Asian middle and upper classes, and between these classes and their counterparts in other areas of the world. Along with fellow Anglo-hybrid elites in their respective countries, Anglo-Chinese parlay their proficiency in the global lingua franca and their familiarity with Anglo-American norms and codes into cultural, social, and material capital.

Ethnic Chinese were erstwhile subject to pressures to declare loyalty to their respective country of residence. During the Cold War, their lack of direct access to mainland China meant that the elder generation, who considered themselves sojourners, could no longer dream of returning to China. The younger generation grew up with the firm notion that their home was in the Philippines, Thailand, or other parts of Southeast Asia. “China” remained for them a geographical and symbolic marker whose image was now mediated by Taiwan and Hong Kong in the form of films, music, television programs, newspapers, and news reports. In the age of collective imperialism, and especially in conjunction with anti-Japanese nationalism, this condition of extended absence from the mainland had already created the phenomenon of “abstract” or “taught” nationalism among the so-called huaqiao.65 In the 1930s to 1940s, this type of nationalism inspired some of them to return to China during the Sino-Japanese war. In postcolonial Southeast Asia across the Taiwan straits, a bitter rivalry between two governments claiming to speak in the name of a legitimate “China” played out in Chinatowns across Southeast Asia, America, and elsewhere. This, despite the fact that younger generations, increasingly rooted in their countries of birth, looked to Southeast Asia for their identities. Some chose assimilation. Others, still identifying themselves as Chinese, practiced a form of abstract nationalism that enabled identification with (an often imaginary) “China” without necessarily supporting either the mainland or the Taiwanese state.66

Moreover, Taiwan and especially Hong Kong emerged as hubs for the popular cultural dissemination of images of and knowledge about China, in the form of newspapers, books, movies, television shows, and pop music. This development was conditioned in large part by the potentials and restrictions inherent in the regional system created in America’s “Free Asia.” The example of Hong Kong cinema in the postwar period is instructive of how conceptual disjunction and historical hybridization influenced the development of the film industry. In the early postwar era, the production of Hong Kong films relied heavily on financing by overseas Chinese and pre-selling to distributors in Southeast Asia. Replacing prewar Shanghai as the “Hollywood of the East,” Hong Kong had a preeminently regional cinema. Starting in the 1950s, during the Cold War, Taiwan emerged as the Hong Kong film industry’s main market and a leading source of non-Hong Kong financing. Hong Kong’s ability to capture the regional market of American-led “Free Asia” was made possible in part by Taiwan’s ruling Kuomintang Party. By classifying Hong Kong films as part of its “national cinema,” it promoted exchanges between Hong Kong and Taiwan (as well as “Free Asia” overseas Chinese communities). This made Hong Kong films eligible for consideration by Taiwan’s film-awarding organizations, and offered incentives for import and production of Mandarin-language films through subsidies and preferential taxation.67 The intensification of indigenous nationalism in Southeast Asia in the late 1960s and 1970s had an adverse impact by restricting the circulation of Hong Kong films as well as Southeast Asian Chinese investment in the Hong Kong film industry. This led to a shift in focus from serving émigré-community markets to developing domestic along with national markets in the region and beyond. Hong Kong’s regional émigré and overseas market in turn defined Hong Kong’s film tradition, genres, and conventions. Mandarin and other Sinophone films of the 1950s drew from the folk opera tradition and prewar Shanghai film conventions of featuring songs, historical themes and settings, and love and martial arts genres68 – conventions on which even mainland Chinese filmmakers had to draw during the past decade when, in collaboration with their Hong Kong and Taiwanese counterparts, they began producing films for the international market.

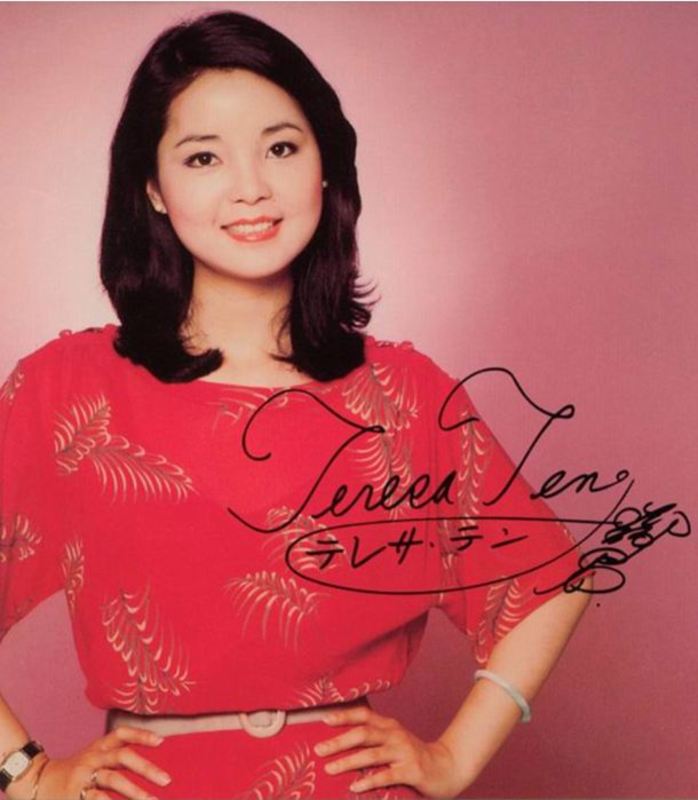

Through the “Free Asia” regional system, Japan also became connected to Hong Kong and Taiwan. In line with the Sino-Japanese-English hybridization of modern China, Shanghai’s film studios in the 1920s and 30s were modeled not only after Hollywood, but also after Japan.69 The postwar period witnessed an increase in popular culture flows from Japan (through film, music, manga, and anime) into Taiwan and Hong Kong. Jidai-geki (pre-Meiji historical drama) films from Japan, for example, inspired Hong Kong filmmakers to create their own swordplay movies. Taiwanese popular music has historical roots in Japanese enka, with superstars such as Teresa Teng (Teng Li-chün, who has a huge fan base in China) cementing their domestic and international reputations by making it big in Japan, and going on to record songs not just in Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese, and English, but also in Korean, Vietnamese, and Indonesian.

|

|

Film technicians were trained in Japan, and Japanese talent was hired in Hong Kong. In the early 1950s, Japanese filmmakers initiated the establishment of the Southeast Asian Motion Picture Producers’ Association and the Southeast Asian Film Festival. This move would eventually lead the expansion of a regional film network under the designations of “Asia” and “Asia-Pacific.”70 Hong Kong films were shot on location in Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines; co-productions and talent inflows were initiated with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand;71 and from the 1970s onward, Hong Kong’s domestic as well as other national markets (rather than just émigré-community markets) in Asia, America, and other areas became an important source of Hong Kong film revenues.

The reopening of China in the late 1970s marked the beginning of China’s economic reintegration with the regional system. Hong Kong, Taiwan and ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs, professionals, and companies in Southeast Asia, America, and other regions played an important role in this process. In sharp contrast, on questions of security, China remains outside the US-led hub-and-spokes system. A look at the cooperative and collaborative connections and networks in and around Hong Kong cinema reveals how the patterns and densities of regional exchanges have changed over time.72 Although China had opened and embarked on reform, in the late 1970s and early 1980s it was still in the process of being integrated into the regional system. The integration of “Free Asia” was already very much in place, as illustrated by the prominent presence of Taiwanese and the importance of Southeast Asian financing and distribution networks in Hong Kong films. Japanese inflows of money and talent peaked at the height of Japan’s bubble years in the 1980s, when the country led the flying-geese pattern of regional development. As China became more integrated into the regional system and emerged as the locomotive of regional development after the Asian financial crisis of 1997-8, mainland Chinese financing and talent inflows gained importance in Hong Kong films. Taiwanese actors/actresses have always formed an important contingent in Hong Kong films; in the 1990s, mainland actors came to constitute an equally important group and overtook their Taiwanese counterparts by the early 2000s.

Large-scale flows and exchanges between Hong Kong and China have resulted in a form of re-Sinicization, defined by Eric Ma as “the recollection, reinvention and rediscovery of historical and cultural ties between Hong Kong and China.”73 Despite the rise of cultural nationalism that has sought to articulate a uniquely Taiwanese national identity (entailing a reassessment of Japan’s role in Taiwan’s modernization), post-Cold War contacts and deepening economic ties with the mainland engendered a “Mainland Fever” in Taiwan that was fed by books, films, and music from and about mainland China.74 In the meantime, the “porous” nature of the regional system has enabled people and capital to go transnational.75 This trend has become clearer in recent years through an increase in the “unclassifiability” of East Asians such as the actor Takeshi Kaneshiro. He holds a Japanese passport, and his father is Japanese and mother Taiwanese. Conversant in Mandarin, Hokkien, Japanese, English, and Cantonese, he debuted as a singer under the Japanese name “Aniki” and gained fame first in Taiwan before appearing in Hong Kong and Japanese films.

The cultural impact of ongoing regionalization is far less understood and remarked upon. Japanization, which reached its peak in the 1980s and 90s as Japan-led economic growth planted the seeds for regional economic integration, has now been subsumed under a broader process of East Asian regionalism and regionalization that has created variegated sources of cultural flows going well beyond Japan and Greater China. It is subject to novel recombinations, as when increasing numbers of mainland Chinese students opt to study in Japan rather than in America, Taiwanese manga artists begin publishing their works in Japan, mainland Chinese produce films using East Asian pop culture formats, Singaporeans follow Hong Kong and Taiwanese fashion trends, Filipinos fall in love with Taiwan’s pop-idol band F4 and Japanese with Korean teledramas, and Koreans learn English in the Philippines rather than in America or Britain. “Re-Sinicization” and Japanization are but two streams of this multi-sited, uneven process of hybridization.76

Some Implications of Multi-Sited “Chineseness”

The conceptual disjunctions and historical hybridizations that make “China” a floating signifier create multiple meanings of and identifications with “China,” “Chineseness,” and “Chinese culture/civilization.” In practice, no single political entity/regime embodies or exercises ultimate authority on “China,” “Chinese,” and “Chineseness.” Although its importance has greatly increased in economic and geopolitical terms, the mainland has so far not emerged as the preeminent cultural arbiter of Chineseness. Indeed, China is distinguished by a relative lack of soft power compared to America.77 Nor have the economic rise of China and the market-driven Mandarinization of “Chineseness” substantively reduced or simplified the multi-sited claims and belongings exercised by the ethnic “Chinese” in Southeast Asia.

What we see, instead, are multiple instances of cultural entrepreneurship that do not necessarily affirm the primacy of mainland China as the cultural center and arbiter of (Mandarin) Chineseness. An example is the Dragon Descendants Museum, located northwest of Bangkok in Suphan Buri Province.

A brainchild of former Thai prime minister (and himself Sino-Thai) Banharn Silpa-archa, the museum was conceived to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Thailand and China. Launched in late 2008, its celebration of “5,000 years” of Chinese history illustrates just how much ideas of China and Chineseness owe to the incorporation of a standardized version of Chinese history, taught in Thai Chinese schools, into the narrative of “Chinese” contribution to the development of Thailand. More telling is its subscription to a version of Chinese history that is mediated by Taiwan’s and Hong Kong’s culture industries. One striking example of this Hong Kong/Taiwan pop-cultural mediation of Chineseness is the prominence accorded to the historical figure of Judge Pao (Bao Zheng), whom Thais came to know through the Taiwanese TV mini-series that was a huge hit not only in Taiwan, but also in Hong Kong and mainland China.78 It was in fact the enormous popularity of the Judge Pao series among Thai viewers that made Chineseness “chic” in the 1990s.79

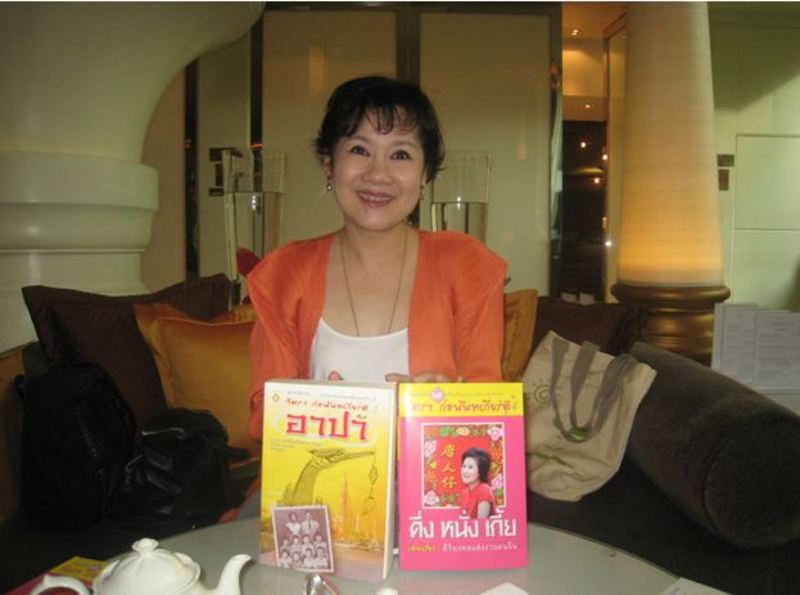

Cultural entrepreneurs like Malaysia’s Lillian Too (born in Penang) and Thailand’s Chitra Konuntakiet (born in Bangkok) have turned Chineseness into a profitable business venture. Lillian Too has built her career on a curriculum vitae that emphasizes her MBA from the Harvard Business School; her position as the first woman CEO from Malaysia to head a publicly listed company, the Hong Kong Dao Heng Bank; and her self-reinvention as founder of the World of Feng Shui. Her Web site sells her English-language geomancy (fengshui) books, which target the “30 million English-speaking non-Chinese Asians” worldwide.80 Educated in an elite school in Thailand before obtaining her master’s degree in the United States, Thailand’s Chitra Konuntakiet overcame her experience of anti-Chinese racism in school by becoming a successful columnist, radio personality, and novelist.

Her books on Chinese culture (as filtered through her Teo-chiu upbringing) – Chinese Knowledge from the Old Man, Chinese Children, Nine Philosophy Stories, and most recently the novel A-Pa – have sold more than 600,000 copies to date.81 Both Lillian Too and Chitra Konuntakiet propound notions of Chineseness that fall beyond the purview of state-sanctioned and mainland-originating discourses: in the case of Lillian Too, through access to a belief system that is not accorded official recognition in mainland China but is part of folk beliefs and practices in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Chinatowns elsewhere, and Mainland China; and in the case of Chitra Konuntakiet, through access to familial memories and ideas of Chinese customs and practices that were rooted primarily in her father’s immigrant experience in Thailand rather than in received notions of Chineseness promoted by the mainland and Taiwan’s China scholarship.82

Enforced for much of the twentieth century by the political turmoil on the mainland, “Chinese” migrants and their descendants’ experiences of extended physical absence from their putative places of “origin” have meant that political contestation over the meanings of “China” extended across the mainland and into Nanyang and Hong Kong. Yet there were important limits to the deterritorialization of these struggles, as illustrated by “the China factor” in the Hong Kong riots of 1967 coinciding with the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.83 Even when political and cultural movements succeeded in capturing the state, their ability to use the state to propound their vision of the “Chinese” nation remains constrained by the limited reach of the “Chinese” state. Through competing strategies of territorialization, deterritorialization, and reterritorialization, authorities and institutions impose constraints on ethnic Chinese, within both Chinese and non-Chinese territories. The spatial, political, cultural, and economic disjunctions that inform the different processes of Sinicization have lent an irreducibly “imaginative” dimension to “Chinese” identification without predetermining the practical consequences and outcomes of these identifications and projects.

Moreover, mainland China has not remained immune to the appeal of these different sources and centers of “Chineseness.”84 An important example of spirited debate on China’s identity in the post-Mao era was sparked by the controversial six-part TV documentary series Heshang (River Elegy, 1988), which relied on the spatial metaphors of land-versus-sea to contrast the isolationism of so-called “traditional” “Chinese” culture, symbolized by the Great Wall, with the openness of the maritime-world “blue” ocean into which the Yellow River flows.85 Some enterprising companies have embarked on making films, set in China, that showcase China’s regional connections and participation in shared urban regional lifestyles. One example is the successful mainland Chinese production of the East Asian romantic comedy genre Lian Ai Qian Gui Ze (My Airline Hostess Roommate, 2009) which deals with a Beijing-based flight attendant who falls in love with her roommate, a Taiwanese visual artist who creates a cute cat character modeled after Japanese anime. Another example is the persistence and continuing popularity of the traditional Chinese script, despite government attempts to impose and propagate a simplified system; traditional script continues to proliferate in China via the Internet, overseas news media, movies, books, and even shop signs (despite government prohibition). Thus it retains its usefulness as a means by which mainland Chinese can communicate with Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities.86 The Chinese government is even promoting the production of cartoon animation, drawing in part on the visual language and conventions of Japanese anime that were popularized through Taiwan and Hong Kong. One example of a successful venture is Xi Yang Yang yu Hui Tai Lang (Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf), a television cartoon series produced by the Guangdong-based Creative Power Entertaining, whose 2009 movie version broke box office records for a Chinese animated film.87 The cartoon series is now aired in 13 Asian countries and regions.88

By erasing their revolutionary past and in its place highlighting local and regional identities that carry traces of “traditional” or “folk” elements, and with the rise of regional/local identities, China’s provinces in the hinterlands have sought to transform themselves into revenue-generating tourist attractions, thus challenging the “ultrastable spatial identity of Chineseness.”89 Nor have coastal provinces been remiss in self-promotion. Tourist-service companies in Xiamen, for example, have turned hybridity into a cultural asset as a way of attracting tourists from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia, with which Xiamen has close historical connections. For example, a tourist brochure put out by the Xiamen Min’nan Tourism and Culture Industry Co. invokes international as well as local contexts to package Xiamen’s attractions. Published in Chinese, English, and Japanese, the brochure features a series of stage shows that celebrate, through song and dance, the heritage of “Magic Min’nan” (Southern Min).90 Min’nan is presented as a hybrid culture, a product of the historical position of Fujian as the “starting point” of the Maritime Silk Road, a “hotbed of reform” that played an important role in the reopening of post-Maoist China, and a “pioneer in the Western littoral of the Taiwan Straits.” Alongside its ancient South China (Guyue) heritage, this brochure plays up Xiamen’s shared cultural links with Taiwan and Inner Asia and its free-port access to the “West” and the world, thus laying simultaneous claim to western-oriented modernity and classical Chinese civilization.

Moreover, the highlighting of a hybrid South China culture with multiple traditions and connections rewrites the narrative of Chinese civilization, stressing its heterogeneity and, in particular, the openness and hybridity of the “south” as opposed to the “north”.91 It affirms an idea first propounded by Fu Ssu-nien (Fu Sinian) and Ku Chieh-kang (Gu Jiegang) in the 1920s and 30s92 and revitalized during the past three decades by new archeological findings that prove the existence of a number of regional cultures (other than the one along the Yellow River in the Central Plains). These regional contacts formed a “core” which, by 3000 BC, linked a geographic area consisting of Shaanxi-Shanxi-Henan, Shandong, Hubei, lower Yangzi, the southern region from Poyang to the Pearl River delta, and the northern region by the Great Wall that would subsequently be called “China.”93 This idea of multiple sources and origins of Chinese civilization decenters the traditional claim of the Yellow River as the cradle of Chinese civilization without relinquishing altogether the idea of a civilizational “core.”

The centripetal and centrifugal forces of territorializing and de/reterritorializing China and Chineseness thus define ethnic-Chinese attitudes and responses toward claims to cultural authenticity by mainland Chinese. The outcry in Hong Kong and Guangzhou against a proposal by the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Guangzhou Committee to increase the ratio of Mandarin-language to Cantonese content in Guangzhou Television’s programming – an attempt to proscribe Cantonese-language coverage of the 2010 Asian Games – indicates that there are limits to how much restriction mainland authorities can impose on the use of local “dialects.”94 Sometimes derided as “culturally inferior” to their fellow “Chinese” on the mainland, some Southeast Asian Chinese have responded by claiming access, via their own local “Chinese” culture, to an authentic “ancient” China that survives through centuries-long, transplanted Chinese customs and rituals no longer practiced – or, for a time, proscribed by the government – in their places of ancestral origins in mainland China.95 Negotiating between their self-identifications as “overseas Chinese” (huaqiao) and “ethnic Chinese” (huaren) has on occasion enabled Southeast Asian Chinese to lay claim to speaking, not in the name of China and Chinese unification, but as the voice of China itself. This happened, for example, in the coverage of Hong Kong’s turnover and the Taiwan Question by the Malaysian Chinese newspaper Kwong-Wah Yit Poh.96 In other cases, the response may take the form of a compensatory gesture of defensive ethnocentrism. An Internet document circulated by and addressed to the “49 million Hokkien-speakers” all over the world, for example, valorizes the Minnan “dialect” as “the imperial language” of the Tang Dynasty and “the language of your ancestors.”97 Advocating a Han-Sinocentric approach while denying the equation of Chineseness with the state-promoted national language, Mandarin, the anonymous author appeals to “all Mandarin-speaking friends out there – do not look down on your other Chinese friends who do not speak Mandarin – whom you guys fondly refer to as ‘Bananas.’ In fact, they are speaking a language which is much more ancient & linguistically complicated than Mandarin.” Mandarin is characterized as an alien tongue spoken by a non-Han minority, “a northern Chinese dialect heavily influenced by non-Han Chinese.” In attesting to its ancient Chinese lineage, this argument is grounded in a comparison of vocabulary and pronunciation, not with other local Chinese “dialects” but with foreign languages such as Japanese and Korean that were part of the “Golden Age” of the Tang China-centered Sinosphere. Such an argument conveniently overlooks the complex ways in which ethnic identity and differences were constructed during the Tang dynasty, and the fact that the ancestry, cultural practices, and geographic focus of the Tang elites were in large part already oriented toward Inner Asia and “barbarized” northern China.98 The above example is revealing of “pressures” brought to bear on Southeast Asian Chinese to learn and speak putonghua/Mandarin, when their “dialects” had long been the basis of their claim to a Chinese ethnic identity. This “Mandarinization” of Hokkien-, Teochiu-, or Cantonese-based “Chinese” identities, however, also constitutes proof of an internal contestation over what “Chinese” means, who can claim Chineseness, who counts as Chinese, and who can “represent” it.

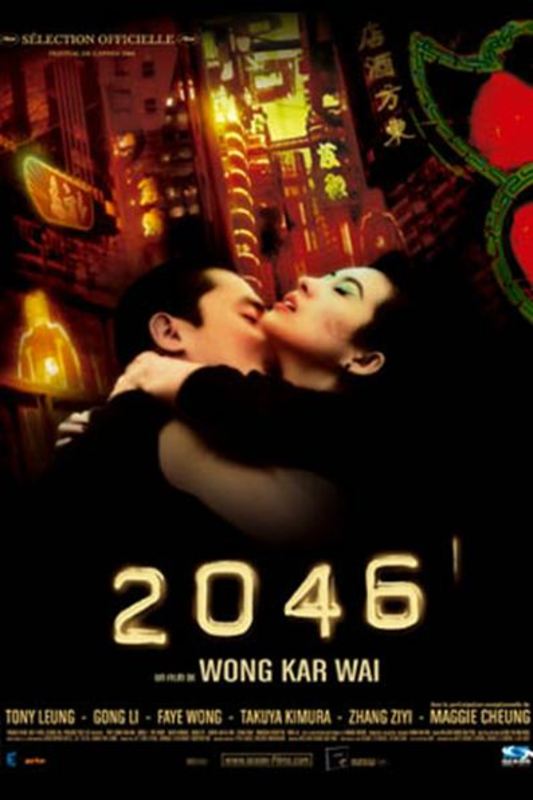

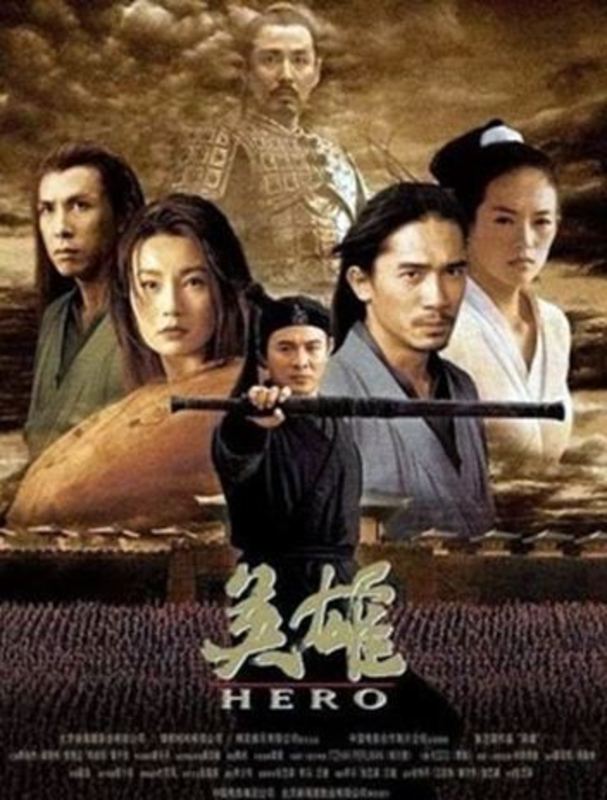

Multiple cultural sites and centers of Chineseness produce different, at times competing, visions of Chineseness. Two opposing views are laid out in Shanghai-born and Hong Kong-based director Wong Kar-wai’s 2046 (2004) and mainland China-based Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002).

Wong Kar-wai’s 2046 (2004) |

Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) |

Set in 1960s Hong Kong, 2046 tells the story of a young author of erotic newspaper serials. Among the women with whom this writer falls in love is his landlord’s daughter, whom he eventually helps to reunite with her Japanese lover. In this movie, Wong not only imagines the possibility of a Japanese-Chinese rapprochement, couched in the language of romantic love and family reconciliation – a vision that stands in stark contrast to the worsening of China-Japan relations owing to Prime Minister Koizumi’s 2001 and 2002 visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. More important, he lets his characters speak to each other in the language with which they are most comfortable, even though Cantonese, Mandarin, and Japanese are in reality mutually unintelligible. The lingua franca is not found in the movie, but rather on the movie, in the form of subtitles, the language of which varies from one market or set of audiences to another. In this way, the film evades the politically charged hierarchy of languages based on the assumed standard set by Mandarin or Putonghua that is audibly rendered in such films as Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2003) and, more problematically, Zhang Yimou’s Hero.

Writes critic and scholar Gina Marchetti,99

In Hero, mainland Chinese director Zhang Yimou also takes a chance, through his proxy Nameless (Jet Li), that the world is ready for the return of the wandering hero. Nameless/Jet Li travels from the PRC to Hong Kong, to Hollywood and back again to China. Hero also repatriates Hong Kong’s Tony Leung (as Broken Sword) and Maggie Cheung (as Flying Snow) as well as Chinese-American Donnie Yen (as Sky) who sacrifice themselves to maintain the Chinese nation-state. The diasporic Chinese from the far edges of the world symbolically capitulate to the central authority of the Emperor Qin (Chen Daoming)/Beijing/the PRC/Chinese cinema.100

Conclusion

Scholars who look at China from a broader, international perspective have generally been wary of subscribing to culturalist arguments. Wang Gungwu,101 for example, offers an important refutation of cultural essentialist arguments about “Chinese” economic success. Such scholars have highlighted instead the importance of the specific situatedness and locations of the “Chinese” in China, Southeast Asia, and beyond. Questions of “roots” and “routes”102 are of paramount concern and have real consequences – including life-and-death ones – for the “Chinese” in Southeast Asia. In making sense of the historical construction of “China,” “Chinese,” and “Chineseness,” in their modern articulations, their concern has been to emphasize the importance of both structure and agency.

Tu Wei Ming’s103 notion of symbolic universes that make up “cultural China,” and Jamie Davidson’s104 attempt to explain the restructuring of Southeast Asian countries by economic globalization as a form of “Chinese-ization” or becoming “structurally Chinese” of urban, middle-class, capitalist Southeast Asian societies, are useful reminders that asserting the heterogeneity and historical variability of “becoming-Chinese” is the starting point, not the concluding statement, of any inquiry into questions and issues of “China,” “Chinese,” and “Chineseness.” The propensity in overseas Chinese studies for taxonomic essays that classify ethnic Chinese according to their political orientations and loyalty is both an instructive symptom of the uneasy fit among the core concepts of territory, people, nation, culture, state, and civilization, and a valiant attempt to catalogue the various manifestations of their critical disjunctions. “Transnational” approaches that purport to move beyond the strictures of nation- and state-centered analysis to stress the “different ways of being Chinese”105 or “deconstruct modern Chineseness”106 offer nuanced case studies. Because they invoke “China” as a self-explanatory straw figure against which transnational or diasporic difference is then asserted, however, they overlook the broader implications of critical disjunctions and historical hybridization. William Callahan’s sophisticated study of “Greater China” is rightly critical of binary thinking in China/West and center/periphery studies, advocating “an understanding of China and civilization in terms of popular sovereignty, heterotopia, and an open relation to Otherness.”107 Yet Callahan’s analysis is marked by aporia with regard to Japan’s mediating role in “Chinese” modernity, be it historical or contemporary. This is apparent in his exclusion of Japan on methodological grounds. Although for Callahan it “is very important to regional economics and is crucial to a geopolitical understanding of East Asia, it is not included here, since Japan is peripheral to the transnational relations and theoretical challenges of Greater China.”108

The “problem of clarifying what ‘China’ is”109 is hardly novel. This article suggests that looking into the pressures and opportunities for “becoming Chinese” by colonial, “China”-driven, post-colonial (national), and market-driven processes of Sinicization in East Asia (a term that now includes Southeast Asia) enables us to specify not just individual differences across time and space, but just as importantly, identify patterns of differences that are historically identified and lived as “Chinese” in China, Southeast Asia, and beyond. Among the most important of these patterns of differences is the identification of “Chinese” with commerce and capital in Southeast Asia; a comparable process happened also in Hong Kong and to the benshengren in Taiwan. Another pattern of difference is the regional circulation of socialist ideas and creation of revolutionary networks in Southeast Asia. The historical incarnation of economic capital by “Chinese” bodies is a personification by which capital, and the “pragmatic” values, habits, and practices associated with it, are actively/passively/forcibly incorporated by living beings as “second nature.” This process cannot be understood apart from the cultural matrices that embed two historical processes: Sino-Japanese-English hybridization after the middle of the nineteenth century; and the Anglo-Sinicization, regionalization, and globalization of the ethnic-“Chinese” in China and Southeast Asia, especially in the second half of the twentieth century.

Patterns of differences also account for the complexity and diversity of “Chinese” responses to, and perceptions, of power and authority in China and elsewhere, which range from enthusiastic accommodation with the mainland state on the part of so-called “Red Capitalist” taipans of Hong Kong, to militant challenges against the colonial state posed by the Communist guerrillas of Malaya, to hedging by Chinese-Filipino businessmen who contribute to the campaign coffers of all presidential candidates. “Chinese” identification with capital has meant a greater awareness of and sensitivity to the arbitrary exactions of the state and the vicissitudes of business. Anglo-Chinese who are safely nationalized and whose citizenships are not in question are under less pressure to be “apolitical” compared to earlier generations of “overseas Chinese.”110 Long distance nationalism, however, continues to shape overseas Chinese responses to mainland China.

The existence of multiple actors, acts, and sites of Chineseness foregrounds the importance of lived experiences in complicating commonsense notions of “Chinese” identity. Civilizational notions of “Chineseness” continue to be haunted by race, nation, and territory. Cultural, political, and circumstantial ideas of “Chineseness” are often articulated as Han-Chinese ethnic identity; and Han-Chineseness as ethnic identity is, in turn, inflected by modern ideas of race.111 Yet these ideas actually encompass older notions of patrilineal kinship that are concerned less with racial purity than with often mythical origins. The genealogy they construct is flexible and capable of transcending place, disregarding physical appearances, encompassing intermarriage and adoption, and incorporating diverse cultural practices, including “non-Chinese” ones.112 Patrilineal kinship may be linked to the ideology of “Confucian culturalism” and its (ethnocentric) claims to absorb “outsiders” and Sinicize them. But as lived experience – and despite the pressures exerted by colonial, “China”-driven, post-colonial and market-driven Sinicization – becoming Chinese is neither preordained nor unidirectional or assilimational.

Rather, Sinicization entails an interactive and dialogical process capable not just of blurring the lines between “self” and “other,” but of transforming them across territorial boundaries and civilizational divides. Viewed in these terms, the phenomenon of “re-Sinicization” might be better understood not as recovery or revival (implied by the prefix “re-”) of long-occluded Chineseness, but as a process of “becoming-Chinese” whose origins are traceable neither to the “core” nor to the “periphery” of so-called “Cultural China,” but to the vicissitudes of the broader phenomena of multi-sited state-, colony- and nation-, region-, and world-making.