Japanese version available here

Here is not the place for a comprehensive account of the deepening crisis of Japan-Okinawa-US relations. The forthcoming study by Satoko Oka Norimatsu and myself attempts to do that in a systematic way (Gavan McCormack and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa vs Japan and the United States, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012.)

Here, however, we present two Okinawan accounts of the events on which the year 2011 ended: one by Okinawa’s leading environmentalist,

By then, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) government, elected at the end of August 2009, was into its third Prime Minister and had abandoned or reversed almost all the key policies on which it had been elected: the commitment to substitute political for bureaucratic direction, the renegotiation of the relationship with the US on an equal basis, the promotion of an East Asian community, the maintaining of the current level of consumption tax, an end to the Liberal-Democratic Party’s long-entrenched “construction state” policies which would be symbolized in particular by the abandonment of the Yamba dam project, and, not least, the closure of Futenma Marine Air Station in Okinawa without substitution in the prefecture.

It is the latter, superficially a “local” issue, that increasingly seems to have the potential to bring the DPJ down and create

The fact is that the DPJ government today faces a level of resistance unprecedented in the history of the modern Japanese state, with the (conservative) Governor, the prefectural Assembly (Okinawa’s parliament), virtually all city, town and village assemblies and mayors, and all media groups and civic and labour organizations firmly opposed to the attempted relocation of the Marine base to Henoko.

The following accounts deal with the submission by the Government of Japan of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) designed to accelerate construction at the projected Henoko site. The story, told here from two different but closely connected viewpoints, reveals the depths to which the DPJ has sunk, its disregard for due process and law, its insistence on the priority that must be attached to service to the US over attention to the interests of its own citizens, its contempt for democracy, and

Just weeks before the “delivery” described here, the head of Okinawa’s Defense Bureau, the local section of the national Ministry of Defense, had to resign over his statement explicitly comparing the delivery of the EIS to rape. When about to commit rape, he said, you do not announce it to your victim in advance. The Government of Japan might have submitted to pressure to replace him in his post, but in the way it went about delivery of the crucial EIS in December, it showed the mentality of the rapist: violent, contemptuous of its victim, and moved by shame to commit its deed at the darkest hour of the night, when witnesses could least be expected.

Gavan McCormack

Canberra, 3 January 2012

The Fatally Flawed EIS Report on the Futenma Air Station Replacement Facility – With Special Reference to the Okinawa Dugong

Sakurai Kunitoshi

The delivery of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the Futenma Air Station Replacement Facility Construction Project was effected today (28 December) at the crack of dawn. At about 4 a.m., the staff of the Okinawa Defense Bureau (ODB) of the Ministry of Defense of the Government of Japan brought the EIS into Okinawa Prefectural Government Office Building. Two days earlier, the ODB had tried to hand it to the Governor but were blocked by a group of citizens opposed to the one-sided approach taken by the ODB in the conduct of the environmental impact assessment (EIA). On the 27th, they tried once again to send it to the Governor using a private courier service but were again blocked by citizens. This questionable submission of the EIS was symbolic of the abnormality of the whole EIA process.

This short note deals with the contents of EIS with regard to the Okinawa dugong. More precisely, it aims to clarify how deficient it is in showing the impact to be caused by the replacement project on the dugong.

According to the Judgment of U.S. District Court (Northern District of California) made on January 23, 2008, DOD (U.S. Department of Defense) is obliged under NHPA (National Historic Preservation Act) to “take into account” the impacts on Okinawa dugong to be caused by their undertaking (the construction and the use of Futenma Air Station Replacement Facility). The “take into account” process at a minimum must include

(1) identification of the protected property (in this case, the Okinawa dugong),

(2) the generation, collection, consideration, and weighing of information pertaining to how the undertaking will affect the historic property,

(3) a determination as to whether there will be adverse effects or not, and

(4) if necessary, development and evaluation of alternatives or modifications to the undertaking that could avoid or mitigate the adverse effects.

These are the obligations of DOD under section 402 of the NHPA. According to the Court, “satisfaction of these obligations cannot be postponed until the eve of construction when defendants (in this case, the DOD) have made irreversible commitments making additional review futile or consideration of alternatives impossible.” The DOD has taken the position that these obligations would be satisfied by Japan’s EIA. Therefore, it is crucial to check the contents of EIS regarding the Okinawa dugong and clarify whether its quality is good enough to satisfy these obligations.

Fatal Defect of the EIS

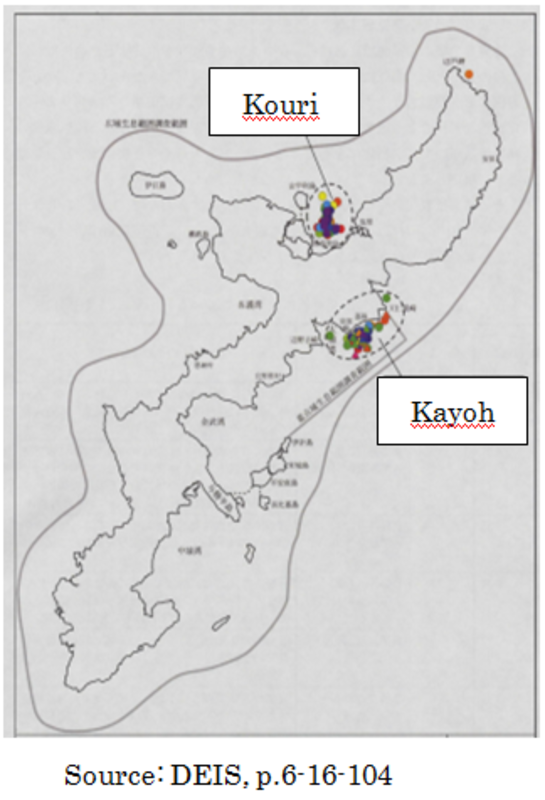

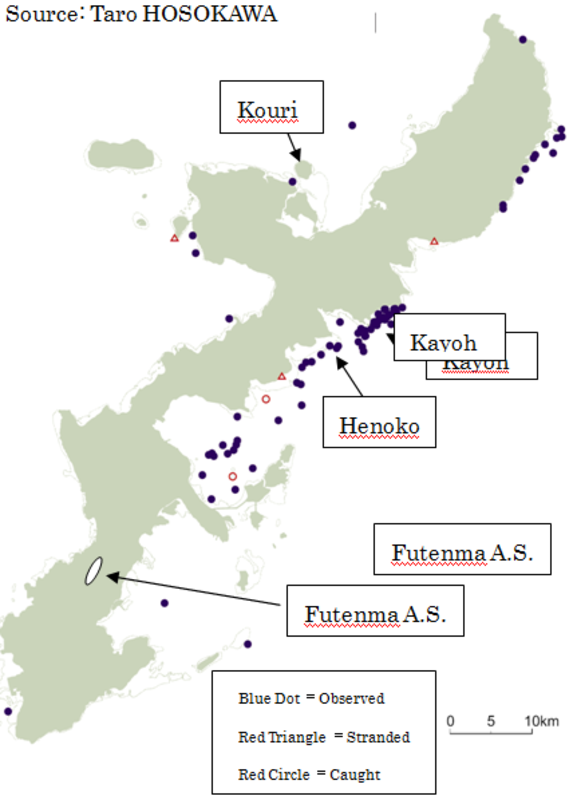

Based on studies conducted from light aircraft and helicopters done after the submission of the Scoping Document (SD) in August 2007, the ODB concluded in its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) submitted in April 2009 that there were three

|

Fig.1 Dugong Identified by DEIS Fig.2 Dugong Observed in the Period of January 1998 – January 2003 |

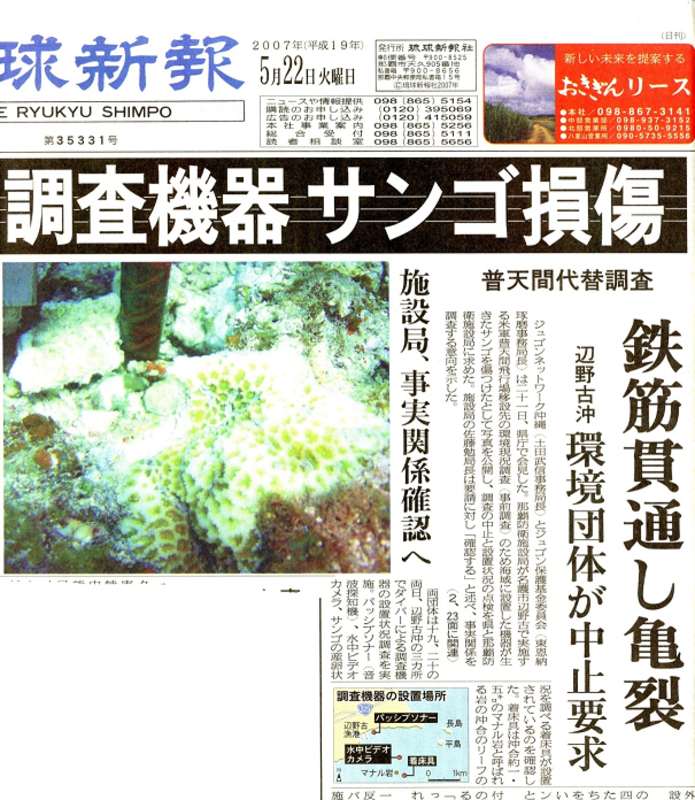

This deduction is quite illogical. As shown in Fig.2, Okinawa dugong used to be observed very frequently along the east coast of Okinawa Island including offshore Henoko. Therefore, DEIS should clarify why they were not observed in the Sea of Henoko during ODB study conducted in the period of August 2007 – April 2009. DEIS, however, made no analysis of this topic. One possible reason they did not appear is the effect of the massive study conducted by ODB at the offshore Henoko area prior to the EIA process that started in August 2007 with the submission of the Scoping Document (SD). The study cost more than 2 billion yen (more than 25 million dollars). The study of coral and

|

Fig.3, Ryukyu Shimpo, May 22, |

It may also be necessary to consider the negative impact on the behavior of dugong of landing drills carried out frequently by (US) marines from Camp Schwab in the Henoko area. Camp Schwab faces the Sea of Henoko which, according to DEIS, is rich in sea grass, the food of dugong. The offshore sea grass area at Henoko is about ten times larger than that of offshore Kayoh. Therefore, there must be some reason why dugong did not visit the offshore Henoko area during ODB study conducted in the period from August 2007 to April 2009. It may well be that the dugong

This massive study was conducted prior to the submission of SD in August 2007, making it very difficult to know what the situation would have been like without the project, and it contravened the spirit of EIA Law that demands the project proponent consult with interested parties at the stage of submission and before the conduct of any large-scale study. Ever since the submission of the DEIS in April 2009, the Okinawan Defence Bureau has been conducting studies in the Sea of Henoko saying that they are collecting additional information including data on typhoon conditions. Many people suspect that ODB is trying to drive away the dugong from the Sea of Henoko in order to maintain their claim that the dugong generally live offshore from

In the Scoping Document, the ODB said that it would forecast qualitatively the impact of the project on dugong studying similar cases and existing information. After the revision of EIA procedures made on March 30, 2006, project proponents were requested to carry out quantitative forecasting and must provide justification when they do not carry it out. In the case of

As for the study of similar cases, on September 13, 2007 when the SD was made available for public inspection I sent my written opinion to ODB asking whether they had any concrete idea about the existence of similar cases anywhere in the world where a dugong population on the brink of extinction was facing the impact of any similar project. I emphasized in that opinion that if they did not have any concrete case in mind, then they were merely copying the Japanese Government’ EIA technical guidelines and their assessment was completely useless. The ODB neglected my opinion and neither the DEIS submitted on April 1,

On April 28, 2009, when the DEIS was made available for public inspection, I sent my written opinion to the ODB asking them to give a rational explanation for the no-appearance of dugong in the Sea of Henoko during the ODB study conducted in the period of August 2007 – April 2009 because the DEIS had nothing to say on that topic. It made no analysis of the impact caused by the massive pre-EIA study on dugong behavior. It did not mention either the impact of

Conclusion

As long as the ODB cannot give any rational explanation for the non-appearance of dugong in the Sea of Henoko during the time of its study from August 2007 to April 2009, it is reasonable to consider that the Okinawa dugong population’s survival chances will be higher if the replacement project is abandoned and the segmentation of Okinawa dugong habitat along the east coast of Okinawa Island avoided.

I hereby declare that the EIS submitted by the Okinawa Defense Bureau does not fulfill the requirements set

Sakurai Kunitoshi

28 December 2011.

Pre-Dawn Surprise Attack: The “Drop-off” of the Environmental Impact Statement

Translation by Gavan McCormack

Urashima Etsuko

I could not believe my ears.

“This morning after 4 a.m., staff of the Okinawa Defense Bureau (ODB) arriving in several station wagons brought in cardboard boxes containing the Environmental Assessment Statement through the Okinawa Prefectural Office tradesman’s entrance to the porter’s room.”

The words of the announcer of the

The Noda government, clinging desperately to “submission of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before the end of the year,” the stance it had adopted to show to the US “progress on the Henoko relocation plan,” was reported to be preparing to submit the report on 26 December, the first day of the last working week of the year. At a cabinet meeting on 24 December, the last day of the preceding week, the Cabinet had decided on the sum of 293.7 billion yen for the Okinawan development budget for 2012, almost the full amount sought by the prefecture and a 27.6 per cent increase on 2011, of which 157.5 billion was to be in the form of direct grant. The Ryukyu

“With budgets being reduced for the prefectures because of the priority to recovery of the areas suffering from the Great East Japan Earhquake Disaster and measures to deal with the nuclear reactor accident, such a substantial increase is unparalleled.

This budget is profoundly coloured by the government’s “concern,” while delaying submission of the EIS, to secure the understanding of Okinawa for the Henoko base transfer.”

In the context of intensive secret negotiations with the government and the democratic party leaders from the beginning of December, with Governor Nakaima publicizing his view that “under the law receipt of the EIS could not be refused,” the suspicion arose that a scenario might have been drawn up with the government for him to agree to the Henoko transfer in return for the budget. The Okinawan media adopted a cautious stance, but sections of the mainland mass media soon began to report that “the Governor is inclining towards acceptance of the transfer” (which might have been what they hoped was happening.).

We members of “Iinagukai” (the Women’s Association for support of Mayor Inamine’s Nago City Government), after an emergency meeting on the night of the 25th, sent a letter of request to the Governor asking him to “please make clear your intention to reject the Henoko environmental assessment” before the opening of business on the 26th. Even if unable by law to refuse to take delivery of the EIS, there was a big difference between silently accepting it and having the government press it on him irrespective of any intent on his part to “reject” it, so we wanted the Governor, in his position as representative of the Okinawan people, to make clear his intent to reject it. We said that such would be a clear indication to the

From the 26th to the 28th, the last day of business for the year, the “Okinawan Association opposed to

On the 26th, with people lined up outside the

|

Protesters at Prefectural Office, Naha, 27 December 2011. Photo: Arakaki Makoto |

Because my health has not been good, I participated just on the 27th (when the delivery by mail was anticipated). Setting off from Henoko at 7 a.m., by the time we of Iinagukai together with comrades from the Henoko Tent Village arrived at the prefectural office after 8 a.m. the watch had already begun over the two entrances for delivery of postal goods and parcels (with civic groups and labour groups dividing the labour) and the underground car park entrance. Pep

|

The Prefectural Office, 27 December 2011. Photo: Arakaki Makoto |

Whenever mail or parcel delivery vehicles appeared we asked them to stop at the entrance from the road so we could check the items they were carrying. Since each copy of the EIS was 7,000 pages and according to law there had to be 20 copies, and since deposit at a Post Office would mean the ODB losing control, and since the Okinawan people knew from previous experiences that the government was renowned for its outrageous lies, we were suspicious of the statement about “postal despatch.”

It must have been quite a nuisance for people making deliveries that day to the Prefectural offices but, perhaps because the submission of the EIS had been widely reported in the media, most were cooperative.

Cardboard boxes were observed on a private delivery company vehicle that arrived just after 11 a.m., and without being able to count them there seemed to be about 20, so everyone gathered around saying, “it must be the EIS.” Shiroma Masaru of the Okinawa Peace Liaison Council, who was the responsible member of the civic groups maintaining the watch,

Perhaps because of fear of a disturbance, the vehicle immediately withdrew, but it came back about 15 or 20 minutes later, most likely ordered by the ODB to make the delivery. As we feared, they made use of a private contractor, over which they could exercise control, rather than the Post Office. People gathered once again around the vehicle. When we pressed the people in the vehicle to move a little further into the Prefectural Office precinct so as to avoid blocking the passage of other vehicles, the driver said, “this is where we have been ordered to be” and switched off his engine. Despite everyone saying “Take it back to the ODB,” he made no move. After about 20 minutes of arguing back and forth, the members of the Prefectural Assembly called the prefectural chief of the accounting section. He borrowed the contractor’s phone, called the ODB and, after confirming that the vehicle contents were indeed the EIS, requested “recall of the vehicle to the ODB because of the dangerous situation.”

At around 12:30, the vehicle withdrew from the Prefectural Office, the assessment document still intact, and applause broke out. However, we remained on guard because of information that the vehicle had stopped at the contractor’s car-park nearby, and fear that it might come back or that the report might be sent in a different vehicle. However, by the close of business at the Prefectural offices, it had not done so. Most likely the contractors were upset at being treated hostilely by their Okinawan compatriots.

Once the Prefectural Office closed, the civic group and the labour organizations moved to the Okinawa People’s Square (in front of the Prefectural Office), led by the group of members of the Prefectural Assembly with raised fists shouting “We stopped them again today,” and “Let’s hold fast for one more day!” A burst of applause rang out when it was reported that representatives of all parties and factions in the Prefectural Assembly, including the LDP and New Komeito, had met that day and issued a “Statement of Protest” against the submission of the EIS. The Statement protested strongly that it was “extremely regrettable” and “absolutely unforgivable” for the government to have completely ignored the 4 November resolution adopted unanimously by the Prefectural Assembly, the representative of the Okinawan people, that called for the submission of the EIS to be abandoned, and instead had been pushing forward by force, using devious measures. It demanded that “relocation within the prefecture be abandoned.” I should also mention that on 19 December, 19 prominent figures, including former Governor Ota Masahide and former Governor Inamine Keiichi (who in his term as Governor had approved the base project) had issued a statement backing the November resolution and calling for it to be widely supported.

Before dawn on the 28th, when Okinawans were still sleeping soundly thinking “Another day and we will have blocked the submission of the EIS before year’s end,” Yamashiro Hiroji, secretary-general of the Okinawa Peace Movement Centre, noticed movement while napping in his car parked near the main gate. Like thieves, the Defence Bureau staff were carrying the report through the side entrance. When he leapt to see what was going on, there

Shouting “What are you up to? Stop!” in an attempt to stop them, Yamashiro was hopelessly outnumbered and 16 cartons were carried to the porter’s room. People gathered quickly in response to the emergency call and sat down in front of the guard room to prevent the report being carried to the appropriate department and “accepted.”

Restlessly, I watched these events unfold from my home, through email and on the television and radio news. It was the top news that day even

“I have said I will not allow construction of a base on land or on sea. So far as Nago City is concerned, this Environmental Impact Assessment is meaningless.”

Okinawan people maintained their sit-in at the Prefectural Office to show that they could not agree with the Prefecture and Governor’s “taking delivery (

“Although as an administrative formality I could not but take delivery I am sticking to my pledge that the base should be transferred to somewhere outside Okinawa.”

In addition, the relevant department head indicated that “The EIS has not been delivered in full and we cannot accept delivery (

We were unable to prevent Governor Nakaima and Okinawa prefecture “taking delivery” of the assessment. Still, I think it can be described as an 80 per cent victory. The reason I say this is because the combined efforts of civic groups and labour organizations had made the staff of the Prefecture and the Governor shift ground. National Diet members and members of city, town and village assemblies all played their part splendidly and could be relied on for liaising with prefectural authorities, relaying requests to the Governor, maintaining a picket line to prevent the EI report being moved from where it had first been carried in, and taking part physically in blocking activities. The combined opposition strength was able to smash the ODB’s scheming and to expose under the light of day just how shameless and wicked (or stupid) it was. As a result the Henoko base transfer became “even more impossible.” Without doubt, the US government, being not as stupid as the Government of Japan, understood this.

Even so, I was really angry that we had to spend year’s end thinking in this vein. Over the past 14

The year 2011, in which human civilization and values were shaken to the core by the catastrophe in Northeast Japan and the nuclear accident, was for Okinawa a year in which confrontation with the Government of Japan’s discrimination continued right up to almost year’s end (while for me

|

Author Urashima, Henoko, 2008. Photo: Gavan McCormack |

Authors

Sakurai Kunitoshi is a member of the Okinawan Environmental Network, professor (to 2010 President) of Okinawa University, and a Councilor of the Japan Society of Impact Assessment. For an earlier essay at this site see his “Okinawan Bases, the United States and Environmental Destruction,” November 10, 2008.

Urashima Etsuko is an environmental activist, author, and chronicler of Okinawan people’s movements of resistance against bases and hyper-development and for nature conservation. The Japanese text of this article was written (dated 29 December 2011) as her regular essay in the monthly Impaction.

Her most recent book (in Japanese)

For her previous article on this site, see: “The Nago Mayoral Election and Okinawa’s Search for a Way Beyond Bases and Dependence.”

Gavan McCormack is a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, Sakurai Kunitoshi, Urashima Etsuko, ‘Okinawa, New Year 2012: Tokyo’s Year End Surprise Attack,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 10, Issue 2 No 1, January 7, 2012.