Therapy for Depression: Social Meaning of Japanese Melodrama in the Heisei Era

Yau Shuk Ting, Kinnia

Abstract: This paper examines the social meanings embedded in Japanese melodramas produced since the 1990s and their use by the public for comfort and healing in an attempt to deal with declining confidence, both personal and national, in the wake of the burst of the bubble economy. It notes, further, how the Japanese media has used similar tropes in an effort to rebuild morale in the aftermath of the March 11 earthquake.

Keywords: Japan, Heisei, bubble economy, melodrama, therapy

Introduction

After World War II, Japan was able to rise from the ashes like a phoenix to emerge as a superpower and a prosperous industrial nation. The death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989, however, marked the end of the Showa era and the start of the Heisei period. Heisei, however, began Japan’s prolonged political, economic and social decline, a period some have termed the Lost Decade(s).1 The bursting of the bubble economy not only triggered a host of social problems, but deeply shook popular confidence. During this difficult period, Japanese have sought ways to heal wounded personal and national pride. Attempts to boost national confidence has often taken the form of memorializing the good old days of Japan. Showa superstars such as Yamaguchi Yoshiko (aka Li Xianglan),2 Ishihara Yūjirō3 and Misora Hibari4

have been repeatedly memorialized.

Yamaguchi Yoshiko (Li Xianglan) exhibit |

Showa superstar Ishihara Yūjirō‘s memorial service |

Misora Hibari – the darling of the Showa era |

They represent a powerful Japan during World War II and the post-war economic miracle. Yūjirō, known as the “sun of Showa” and the “most lovable Japanese man in history,” is remembered for his confidence and exceptionally long legs (90cm). In 2000, a competition titled “Search for the twenty-first century Yūjirō” attracted as many as 52,500 contestants.

Apart from the Showa icons, Kimura Takuya is another figure frequently used to lift the country’s confidence. Since the mid-1990s, he has played in a number of TV dramas as a dreamer who refuses to give up during difficult times.5

SMAP member and top idol, actor Kimura Takuya |

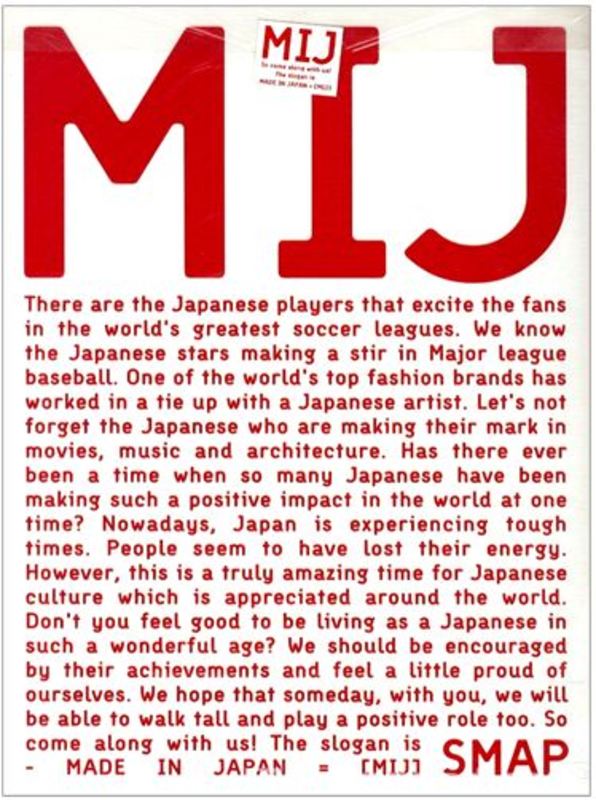

On June 16, 2003, Kimura Takuya and his group SMAP sponsored a full-page advertisement called “MIJ” (Made in Japan) in Yomiuri shimbun to promote their new album of the same title.

“Come On” and be the 21st Century Yūjirō |

Top boy band SMAP taking pride in “MIJ” |

They highlighted the remarkable achievements of Japanese people throughout the world. Their CD cover asks, “Don’t you feel good to be living as a Japanese in such a wonderful age?”6 In addition, sport stars such as Suzuki Ichirō, Nakata Hidetoshi, Asada Mao and Ishikawa Ryo enjoy unparalleled popularity mostly because of their international success.

In recent years, movies with a strong sense of romanticized nostalgia for post-war Tokyo have become a trend in Japanese cinema. One of the best examples is Yamazaki Takashi’s Always: Sunset on Third Street (2005) and Always: Sunset on Third Street 2 (2007).7

Always film poster |

Poster for the Always sequel |

The story is set in 1958 in a poor but warm Japanese community where the residents are friendly and helpful. The 2005 film swept 12 prizes at the 2006 Japanese Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Screenplay. Other box-office hits like Memories of Matsuko (2006, Nakashima Tetsuya)

Tokyo Tower: Mom, and Me, and Sometimes Dad (2007, Matsuoka Jōji) and 20th Century Boys (2008, Tsutsumi Yukihiko) are also movies that project an innocent, warm and energetic Showa in contrast with the sinful, cold and frustrating Heisei.

Memories of Matsuko film poster |

20th Century Boys manga |

Many Japanese melodramas since the 1990s employ the theme of resurrection. They can also be seen as romanticized nostalgia for the past, especially the 1980s when the Japanese economy reached its historical peak. This paper proposes that melodrama serves as therapy for the national depression primarily caused by the burst of the bubble economy and the subsequent prolonged recession. It should be noted that the term depression applies not only to severe contraction but also to psychological damage including loss of confidence triggered by the prolonged financial crunch. Analysis of such classic Japanese melodramas as Love Letter (1995, Iwai Shunji), Be with You (2004, Doi Nobuhiko) and Crying out Love, in the Centre of the World (2005, Yukisada Isao), reveal that the directors seek to comfort audiences through re-experiencing a sweet past. Most importantly, these melodramas can boost Japanese confidence as they seek to pierce the gloom of the Heisei period.

Generation X directors

The movies discussed in this paper are primarily those directed by Japan’s Generation X or shinjinrui (new breed).8 Born between 1958 and 1967, they grew up in an environment free of war and poverty and were the prime beneficiaries of the country’s rapid economic growth generated by older generations. But they were also hit the hardest by the burst of the bubble economy. Frustrated with the current situation, they became nostalgic for the glorious Showa era. The deteriorating living standard of Japanese households also led to the creation of failed father figures, who are usually the breadwinners. Fathers or husbands who become unemployed as a result of company downsizing were even labeled dame oyaji (loser dads) and sodai gomi (oversized garbage).9 In the face of degrading masculinity, it is not surprising that Generation X directors, traumatized by Japan’s economic failure, became the most nostalgic for the 1980s. Japanese melodramas produced since the 1990s therefor often involve the death and resurrection of a loved one. In many cases, the beloved is a metaphor of Japan’s golden age. Among Japanese melodramas of this nature, Love Letter can be considered the original and most important classic.

Love Letter

Love Letter film poster |

Love Letter tells the story of Watanabe Hiroko (Nakayama Miho) who is unable to cope with the death of her fiancé Fujii Itsuki.

On the third anniversary of his death, Hiroko sends a letter to Itsuki’s old address. The letter is received by a female “Itsuki” (also played by Nakayama Miho) who writes back. It turns out that the two Itsukis were actually in the same class in high school. Flashbacks reveal that the male Itsuki (Kashiwabara Takashi) was in love with the female Itsuki (Sakai Miki) but she was never aware of it. Having realized that she is not her fiancé’s true love, Hiroko decides to move on with her life. A blockbuster, Love Letter was nominated for the Best Film Award at the 19th Japan Academy Awards, while Kashiwabara and Sakai received the Best New Actor Awards. Love Letter made the city of Otaru a famous tourist spot, but it has even more significant influence on post 1990s Japanese melodramas.

Post 1990s Japanese melodramas

Be with You and Crying out Love, as well as other post 1990s Japanese melodramas carry indelible traces of Love Letter.10 The most common plot of a Japanese melodrama involves the protagonist’s loss of a loved one. He or she cannot overcome the trauma until the deceased returns. Furthermore, the deceased usually returns to encourage those living in reality to look to the future. At the end, the protagonist generally lets go of the past to start a new chapter in life. However, these melodramas are more than just tear jerkers. They also convey nostalgia for Japan’s golden age, that is, before the burst of the bubble economy.

The main actors of Be with You |

Japan lost its magic power in the early 1990s while other Asian countries, notably Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, and of course

China were emerging as newly industrialized economies. South Korean conglomerates like Samsung and Hyundai became strong competitors for Japanese firms. Imitating Japanese management style, they successfully captured some of Japan’s market share. Rapid development of the Chinese economy also meant that China would surpass Japan in 2011 to become the world’s second largest economy,

though still a far less prosperous nation.11 Within East Asia, controversies over history textbooks, comfort women and Yasukuni Shrine isolated Japan, undermining relationships with Asian neighbors who remain heavily conscious of historical issues centered on Japanese colonialism and war.12 Inside Japan, an unstable political environment continues to overshadow the country’s future outlook. Although Koizumi JunIchirō held power for six years, his three successors were each forced to step down in about a year’s time, indicative of political instability.13 Confronted by internal and external problems, Japanese people are in need of therapy to infuse hope and courage. Post 1990s Japanese melodramas, this paper proposes, serve this purpose.

Be with You

Be with You is a melodrama filled with nostalgia for Japan’s golden age.

It tells the story of Takumi (Nakamura Shidō), a single father who cares for his son after his wife Mio (Takeuchi Yūko) dies. A year after Mio’s death, she reappears and the three again become a family once more. When the rainy season ends, however, Mio must leave and never return again. Typical of post 1990s Japanese melodrama,

Love Letter‘s Itsuki |

Mio is pure, caring and perfect.14 She provides comfort and therapy to people around her. On the other hand, Takumi is a pessimistic introvert who lacks self-confidence. An acute sickness deprives him of his talent at running, the only skill he took pride in. This heavy blow can be seen as a metaphor for the abrupt end to Japan’s glory days. Both Takumi and Japan find it difficult to stand on their feet again. Takumi’s son, who represents the younger generation of Japanese, is disappointed with his father. Before she leaves for good, however, Mio reminds her son that, “There was a time when Daddy was an incredibly fast runner, he looked really cool.” Her words can be interpreted as a message for young Japanese that their Japan was once an outstanding nation. Therefore, they should respect and take pride in their country even at difficult times.

Top 80s idol Matsuda Seiko |

Like Love Letter, Be with You also depicts the female and male protagonist falling in love. Judging from clues in the movie, Mio and Takumi probably went to high school in the 1970s or 1980s, that is, when Japan was at the peak of its success. Their teenage years were always blessed with sunny weather. The scene in which Mio and Takumi kiss in the middle of a sun-drenched sunflower field, in particular, is representative of this type of vibrant impression. Mio represents the good old days and her presence guarantees fine weather and bright skies.15 Her perfection means that even her death would not cause any disturbance. In much the same manner, the death of male lead Fujii Itsuki is also only briefly touched upon in Love Letter.

Notably, Itsuki is said to have sung Matsuda Seiko’s hit song Aoi sangoshō (Blue Coral Reef) moments before he dies. Coincidentally, Matsuda, recognized as Japan’s “eternal idol,” is one of the best known pop icons in the 1980s who was tipped to become the next Yamaguchi Momoe.

Mio, Itsuki and the golden age are badly missed because they are irreplaceable. Indeed, “love of life” is commonly used in post 1990s Japanese melodramas to symbolize the “golden age.” Other examples include Kazuya in Touch (2005, Inudō Isshin), Haruhi in The Angel’s Egg (2006), and Togashi Shin and Aoi in Rainbow Song (2006, Kumazawa Naoto).

Hit drama Angel’s Egg |

Protagonists of Rainbow Song |

As soon as these characters die, the film’s cheerful mood comes to a sudden end. It is as if all things bright and beautiful have disappeared with the loved ones. The remarkably glamorous Showa period dies and the depressing Heisei era sets in.

Crying out Love, in the Centre of the World

Adapted from a novel of the same title, Crying out Love tells a bittersweet love story between Sakutarō (Moriyama Mirai) and Aki (Nagasawa Masami).

The couple became attracted to each other when studying in the same class. Again, this mostly likely took place in the 1980s. Sakutarō considers Aki the love of his life, but she dies from leukemia at a young age. When visiting his hometown on the island of Shikoku, the now grownup Sakutarō (Ōsawa Takao) becomes mesmerized by memories of Aki. The thought of Aki dominates his life, almost costing him his fiancée Ritsuko (Shibasaki Kō). After listening to the last words Aki left behind, Sakutarō finally has the courage to walk out of the past and start a new life. This is precisely depicted in the film’s theme song Hitomi wo tojite (Close Your Eyes) by Hirai Ken, in which the last phrase says, “I shall search for you in my memory; that alone is sufficient, because you gave me strength to overcome the loss, you gave me that.”16

Aki, like Love Letter‘s Itsuki and Be with You‘s Mio, represents the good old days. Her death is accompanied by a rainstorm which foretells the arrival of a dark era.17 The frequent appearance of props such as Walkman and cassette tape locate the story takes place in the 1980s.

|

|

Invented by Sony in 1978, Walkman is a revolutionary device held to be representative of Japanese creativity. It is one of the proudest creations of Japan’s glory days. The 1980s, a period in which Aki lives, is characterized by warm and sunny weather. Fine weather prevails when she is healthy and energetic. One the other hand, severe weather such as typhoon and rainstorm occur as her health condition deteriorates. At the end of the film, the sun reappears when Sakutarō realizes he should leave the past behind and live the moment with Ritsuko. The most important purpose of the deceased’s return, then, is to encourage the living to look forward to a bright future. Therefore, these Japanese melodramas usually end with the return of fine weather

March 11 Earthquake and a Prouder Japan

The March 11th earthquake threatened Japanese confidence yet again. The humanitarian , social and economic crisis cast uncertainty over a nation still struggling to find its footing two decades after the burst of the bubble economy. Japanese artists are among those doing their part to heal the nation. Shortly after the earthquake, renowned actor Watanabe Ken18 launched a website called “Kizuna311″with writer Koyama Kundo. The website, which contains messages of courage, hope and love for victims of the disaster, calls for “Kizuna – Unity and Hope. Together we will prevail and overcome.” Apart from visits to quake-stricken area, Watanabe held advance screenings of his latest movie in Iwate and Miyagi, two hard-hit prefectures. The film, Hayabusa: Haruka naru kikan (Hayabusa: The return from afar) (2012, Takimoto Tokiyuki) tells of Japan’s development of an unmanned spacecraft aimed at retrieving a sample of material from an asteroid similar to the Earth.

Watanabe Ken stars in Hayabusa |

The actual Hayabusa project, headed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency(JAXA), was a milestone Japan’s aerospace technology.19 It symbolizes Japanese ability to overcome difficulties. Watanabe plays Professor Yamaguchi, a character modeled after Kawaguchi JunIchiō, Hayabusa’s project manager. Released in February 2012, the film’s tagline is, “‘Zettai ni akiramenai’ Nihon no gijutsuryoku ningenryoku ga sekai wo kaeru” (The persistent power of Japanese technology and people change the world). While it may not be an all-out melodrama, the film aims to boost morale and strengthen the nation by re-presenting a story of Japanese creativity and perseverance in space at a time when the country has been severely shaken.

In a similar sense, TV network TBS’s 60th anniversary drama Nankyoku tairiku (Antarctica) which was broadcasted between October and December 2011 can also be considered an attempts to boost Japanese pride in the aftermath of the March 11 earthquake.

Whatever the original reasons behind the drama’s conception, it has clearly been used to comfort a deeply shocked nation. Antarctica sends a message similar to Hayabusa: Haruka naru kikan, its tagline reads, “Sono yume ni wa, Nihon wo kaeru chikara aru” (That dream has the power to change Japan). In the drama, Kimura Takuya plays a member of Japan’s first Antarctic expedition team. The story takes place about 10 years after WWII when Japan was still struggling to regain confidence and international recognition. Trying to share in the exploration of Antarctica, Japan was largely condemned by other countries due to its defeated nation status. Kimura is portrayed as a man who strives to bring Japan back on track to become a major player on the world stage. The determination and charisma of one of Japan’s most beloved artists without doubt have a therapeutic effect on the audience.

A more direct attempt to address the March 11 earthquake is NHK’s drama Sorekara no umi (The Sea from Then On). The special drama, starring victims of the disaster, is scheduled to air on March 3, 2012. Shot in Iwate prefecture, it tells the story of a school girl who lives in the makeshift house with her father and grandfather after losing her mother in the tsunami. As Japan gradually recovers from the catastrophe, more films representing the March 11 earthquake should be expected.

Conclusion

During the Heisei period, in the wake of the burst of the bubble, resurrection of a loved one has become a trend in Japanese cinema. In the past two ‘Lost Decades’, Generation X directors have produced numerous melodramas with similar themes, setting and plot. Post 1990s Japanese melodramas allow the audience to re-experience Japan’s golden age. They bring back happy memories which many Japanese, especially those of Generation X, try desperately to preserve. At the same time, these melodramas also express the directors’ dissatisfaction with the present situation and deliver a positive message that encourages the audience to accept their loss and face future challenges with hope and confidence. Most importantly, audiences are reminded that their country can build an even greater miracle than before. A line from Mitani Kōki’s The Magic Hour (2008) says, “As long as there is tomorrow, there will always be a chance to come across the most beautiful ‘magic hour’ of the day.” Hope and faith, therefore, are crucial to rebuilding Japanese confidence.

In the wake of the March 11 earthquake, the Japanese entertainment industry has been doing its part to heal the nation and more films and TV dramas have been produced that depict love, hope and courage. How the disaster itself will be portrayed remains to be seen, but restoration of national confidence and pride in a wide range of media products appear to be the mainstream. It is possible that the disaster could help unite a nation that has somehow lost confidence. It offers a chance for Japan to reestablish its position as a leading world player. The production of films that assert Japanese achievements, in ways similar to the melodramas, could strengthen a nation severely traumatized by the tragedies.

Yau Shuk-ting, Kinnia received her Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo in 2003. She is Associate Professor at the Department of Japanese Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Kinnia is the author of Japanese and Hong Kong Film Industries: Understanding the Origins of East Asian Film Networks (Routledge, 2010), Chinese-Japanese-Korean Cinemas: History, Society and Culture (The Hong Kong University Press, 2010), and the editor of East Asian Cinema and Cultural Heritage: From China, Hong Kong, Taiwan to Japan and South Korea (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). Her latest book, An Oral History of Japanese and Hong Kong Filmmakers: From Foes to Friends (The Hong Kong University Press, 2012) will be published soon.

Email: [email protected]

Recommended citation: Yau Shuk-ting, Kinnia, ‘Therapy for Depression: Social Meaning of Japanese Melodrama in the Heisei Era,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 11, No 4, March 12, 2012.

Responding to Disaster: Japan’s 3.11 Catastrophe in Historical Perspective

Is a Special Issue of The Asia-Pacific Journal edited by Yau Shuk-ting, Kinnia

See the following articles:

• Yau Shuk-ting, Kinnia, Introduction

• Matthew Penney, Nuclear Nationalism and Fukushima

• Susan Napier, The Anime Director, the Fantasy Girl and the Very Real Tsunami

• Yau Shuk Ting, Kinnia, Therapy for Depression: Social Meaning of Japanese Melodrama in the Heisei Era

• Timothy S. George, Fukushima in Light of Minamata

• Shi-lin Loh, Beyond Peace: Pluralizing Japan’s Nuclear History

• Brian Victoria, Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima

See the complete list of APJ resources on the 3.11 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear power meltdown, and the state and societal responses to it here.

NOTES

1 In the years following the burst of the bubble economy, especially between 1991 and 1998, Japan’s GDP continued to drop at the rate of one percent every year. See Yoshikawa Hiroshi, Japan’s Lost Decade (trans. Charles H. Stewart), Tokyo: The International House of Japan, 2002.

2 Yamaguchi Yoshiko was born in Manchuria in 1920. Her father worked for the South Manchuria Railway and she was raised in China. Pro-Japanese figures Li Jichun and Pan Yugui who became her adoptive fathers and gave her alternative names Li Xianglan and Pan Shuhua. She made her debut in a Man’ei film Honeymoon Express (1938, Ueno Shinji) with the stage name Li Xianglan. Becoming one of the company’s top stars, she took part in numerous “national policy films.” Her works include Japanese films: Journey to the East (1939/Otani Toshio), China Nights (1940, Fushimizu Osamu), Eternity (1943, Bu Wancang and others) and Sayon’s Bell (1943, Shimizu Hiroshi); Hong Kong-Japanese collaborations: The Lady of Mystery (1957, Wakasugi Mitsuo), and The Unforgettable (1958, Bu Wancang). Yamaguchi’s Japanese identity was kept secret until Japan’s surrender when she was charged with being a “traitor.” After the war she starred in Japanese and American films, as well as Hong Kong’s Shaw and Sons’ musicals. Yamaguchi, who was once a superstar in China, provides an example of a Japanese who enjoyed immense popularity in a foreign country.

3 Ishihara Yūjirō (1934-1987) was born in Kobe. He debuted in Season of the Sun (1956, Furukawa Takumi), a film adaptation of his elder brother Ishihara Shintaro’s novel. Subsequent films such as Crazed Fruit (1956, Nakahira Kō) and Man Who Causes a Storm (1957, Inoue Umetsugu) made him a superstar and icon of the “sun-tribe” culture. Yūjirō’s rebellious and energetic character made him one of the best loved Japanese actors of the Showa period. However,plagued by illness during the last year of his life, he died of liver cancer at the age of 52. The Ishihara Yūjirō Memorial Museum opened in June 1991 in Hokkaido’s Otaru, a city where he spent part of his childhood.

4 Misora Hibari (1937-1989) was born in Yokohama. Her singing talent was recognized at a very young age. At 12, she began her career in a movie called The Age of Amateur Singing Manias (1949, Saitō Torajirō). Her performance in Dancing Dragon Palace (1949, Sasaki Yasushi), a film in which she also sang the theme song, captured national attention. Throughout her career she played in over 160 films including Sad Whistling (1949, Leki Miyoji), Tokyo Kid (1950, Saitō Torajirō), Hibari’s Lullaby (1951, Shima Koji) and The Dancing Girl of Izu (1954, Nomura Yoshitaro). A best-selling singer, she was also a frequent guest of NHK’s annual kōhaku music show. Her death at the age of 52 was widely mourned. The Misora Hibari Museum was opened in Kyoto’s Arashiyama in 1994.

5 Some of his best known TV dramas are Long Vacation (1996, Fuji TV), Beautiful Life (2000, TBS), Pride (2004, Fuji TV), The Grand Family (2007, TBS), Change (2008, Fuji TV) and Mr. Brain (2009, TBS).

6 Just as SMAP tried to boost the country’s confidence with their album, Hirai Ken’s latest album is titled Japanese Singer. Released in June 2011, three months after the March 11 earthquake, this title carries special meaning to Hirai because he is often mistaken for a foreigner due to his Westerner-looking face. In an interview with CNN, he spoke of his insecurity for not looking like typical Japanese. See “Hirai Ken Talk Asia Interview,” February 28, 2007. Available here (accessed 7 September 2011). Furthermore, Japanese Singer can also be seen as emphasizing national identity. The CD cover features him holding a red ball, which can immediately be associated with Japan. See “Hirai Ken sannen buri no furu arubamu ga ririsu kettei” [Hirai Ken’s new album in three years to be released], Cinema Today, May 10, 2011. Available here (accessed 6 September 2011). In fact the “rising sun,” usually accompanied by slogans like “Nippon ganbare, Tōhoku ganbare” (Don’t give up, Japan; don’t give up, Tohoku), has frequently appeared in the Japanese media since the earthquake. In the same manner, The Economist features an illustration by Jon Berkeley which shows rescuers struggling to stop a giant red ball from rolling downhill. See “The Fallout,” The Economist, March 17, 2011. Available here (accessed 6 September 2011). In an attempt to raise funds for quake-stricken Japan, designer brand Kate Spade released a limited edition tote bag. It features a “spade,” a “heart” and a “rising sun.”

7 The latest of the series Always: Sunset on Third Street ’64 is scheduled for release in early 2012. The story takes place in 1964, the year of the Tokyo Olympics.

8 Examples of Generation X directors include Sasabe Kiyoshi (1958), Inudō Isshin (1960), Togashi Shin (1960), Shiota Akihiko (1961), Shinohara Tetsuo (1962), Iwai Shunji (1963), Doi Nobuhiro (1964) and Yukisada Isao (1968). Original authors from this generation include Katayama Kyōichi (1959) who wrote Crying out Love, in the Centre of the World, Ichikawa Takuji (1962) who wrote Be with You and Heavenly Forest, Murayama Yuka (1964) who wrote The Angel’s Eggs, Asakura Takuya (1966) who wrote The Gift and, Tanaka Wataru (1967) and Matsuhisa Atsushi (1968) who co-wrote Heaven’s Bookstore.

9 Battle Royale (2000, Fukasaku Kinji), Ju-on: The Grudge (2003, Shimizu Takashi) and Death Note (2006, Kaneko Shusuke) are works that blame incompetent fathers. By contrast,, Poppoya Railroad Man (1999, Furuhata Yasuo), Departures (2008, Takita Yōjirō) and Tokyo Sonata (2008, Kurosawa Kiyoshi) are movies that stress contributions by fathers.

10 Collage of Our Life (2003, Tsutsumi Yukihiko), Yomigaeri (2003, Shiota Akihiko), A Heartful of Love (2005, Shiota Akihiko) and Heavenly Forest (2006, Shinjo Takehiko) are other examples of post 1990s melodrama.

11 Cary Huang. “Bigger than Japan – now what?” South China Morning Post, August 17, 2010.

12 On September 7, 2010, Chinese fishing boat captain Zhan Qixiong was arrested by Japan after his boat collided with two Japanese Coast Guard patrol boats. The Japanese Ambassador to China, Niwa Uichirō, was summoned by the Chinese government on several occasions in protest against what the Chinese side argued was the illegal detention of Zhan. The arrest sparked anti-Japan protests across China and anti-China protests subsequently broke out in Japan. Sino-Japanese relations hit an all-time low. The two countries did not resume ministerial exchanges until late February 2011.

13 Following Abe Shinzō, Fukuda Yasuo, Aso Tarō and Hatoyama Yukio, Kan Naoto became the latest Japanese prime minister to resign. Noda Yoshihiko succeeded him as Japan’s prime minister.

14 Takeuchi Yūko also played in Yomigaeri, Night of the Shooting Stars (2003, Togashi Shin), Heaven’s Bookstore (2004, Shinohara Tetsuo), Spring Snow (2005, Yukisada Isao), Closed Note (2007, Yukisada Isao), Flowers (2010, Koizumi) and Wife and My 1778 Stories (2011, Hoshi Mamoru). She is regarded as one of the iyashi kei (healing type) representatives. The iyashi kei phenomenon originated from Iijima Naoko’s 1995 canned coffee commercial which was said to be a “spiritual retreat” to the audience. The term iyashi kei, however, first appeared in 1999 when Sakamoto Ryuichi’s EP Ura BTTB was described as “iyashi ongaku” (healing music). From then on, whoever (for example Yūka and Bae Yong-joon) or whatever (cute soft toys) is soft and carries “healing” power can be appreciated as iyashi kei.

15 Likewise in Love Letter, the young male Fujii Itsuki is always showered in sunlight.

16 The original lyrics are 瞳を閉じて 記憶の中に君を探すよ それだけでいい なくしたものを 越える強さを 君がくれたから 君がくれたから

17 Nagasawa Masami is another icon of Japanese melodrama. She also features in Touch, a film that depicts a period characterized by unity and harmony. Both Touch and Rough (2006, Ōtani Kentarō), also starring Nagasawa, are adaptations of Adachi Mitsuru’s comic. Touch is a 126-episode comic series published between 1981 and 1987. The young characters are energetic and their parents are warm-hearted. The series is a symbol of the 1980s, and the perfect picture it portrays is in sharp contrast with the dysfunctional families in Japanese films produced after the 1990s.

18 Watanabe Ken is one of Hollywood’s best known Japanese actors. Some of his works include The Last Samurai (2003, Edward Zwick), Memoirs of a Geisha (2005, Rob Marshall), Letters from Iwo Jima (2006, Clint Eastwood) and Inception (2010, Christopher Nolan).

19 Having overcome a series of troubles and accidents, the spacecraft finally returned to earth in June 2010. The story caught the attention of filmmakers and four films about it have already been produced. Apart from Watanabe’s film, documentary Hayabusa Back to the Earth (2011, Kōsaka Hiromitsu), Hayabusa (2011, Tsutsumi Yukihiko) starring Takeuchi Yūko, and Okaeri, Hayabusa (2012, Motoki Katsuhide) starring Watanabe Ken’s daughter Anne, are also inspired by the event.