Nuke York, New York: Nuclear Holocaust in the American Imagination from Hiroshima to 9/11

Mick Broderick and Robert Jacobs

Discussed Manhattan (it is a success). Decided to tell Stalin about it […Believe Japs will fold up before Russia comes in. I am sure they will whenManhattan appears over their homeland.

-President Truman, Personal Diary, July 18, 1945

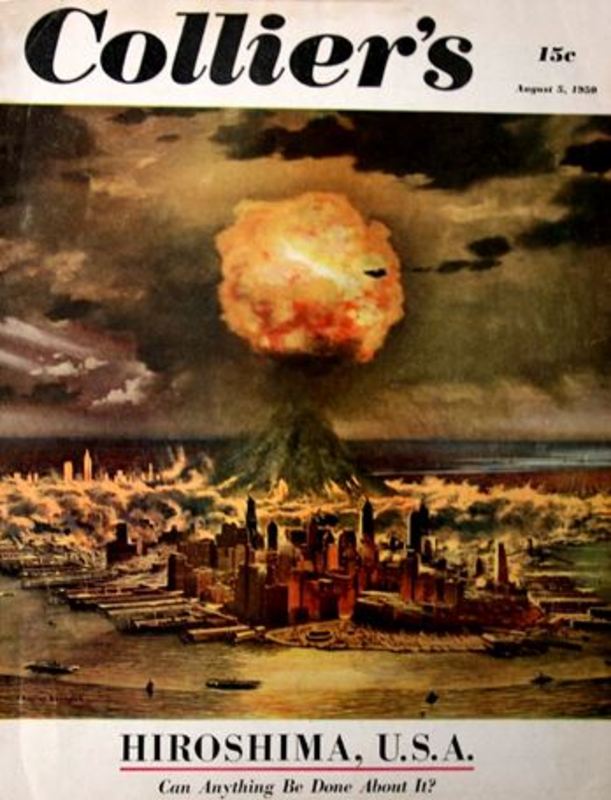

Collier’s, 5 August 1950. Cover art by Chesley Bonestell. |

Introduction

Almost immediately after 9/11, cultural tropes that had long been associated with the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were relocated to new roles as descriptors of the attack on New York City. Where once terms like “ground zero” referred to the detonation points of the nuclear weapons that were dropped in Japan, Ground Zero now refers to the site where the World Trade Center towers once stood in lower Manhattan.1 This appropriation of framing mechanisms from Hiroshima and Nagasaki to New York City was nothing new: it held true to an American tradition that began in August of 1945. When Americans felt that bifurcated sense of victory and vulnerability upon the news of the bombing of Hiroshima, it was a short journey for the word Hiroshima to take on a second, shadow meaning in American culture—it became shorthand for fears of an inevitable nuclear attack on America itself—and almost always the target of this imagined attack was New York City. While Lifton and Mitchell claim that, “Hidden from the beginning, Hiroshima quickly disappeared into the depths of American awareness,” we have found instead that it became ubiquitous in American culture and remained so throughout the Cold War and beyond, particularly as shorthand for America as nuclear victim, not nuclear perpetrator. 2 This same inclination can be seen in early press coverage of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan last year. A great deal of press coverage in the United States was focused on the dangers of radioactive contamination on the American West coast, on America as vulnerable and a victim.3 This inversion of the history of Hiroshima and Nagasaki took a firm hold on the American imagination once the former Soviet Union developed nuclear weapons of their own in late 1949. However, even with the end of the Cold War, the 9/11 attacks reinvented notions of an American Hiroshima as the inevitable follow-up to the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

On the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks we staged the first public showing of the Nuke York, New York exhibition at the Hartell Gallery, Cornell University.4Nuke York, New York exhibited of a broad range of depictions of a nuclear attack on New York City drawn from American popular culture from 1945 to 2011, including sources from newspapers, magazines, Civil Defense pamphlets, film, television, books, protest material, comics, computer games, online websites and material culture objects. This article presents

Superimposed image from the official pictorial history, Operation Crossroads, 1946. |

an overview of the material exhibited in the Nuke York, New York installation and its significance for reflecting on the bomb in American historical memory and representation.

In the years prior to the July 1945 Trinity test in New Mexico and the August 1945 atom bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the city of New York was already implicated. As Truman’s diary note attests, “Manhattan” was the ubiquitous code name designated for the top-secret $2 billion allied wartime research project. Terms such as ‘Manhattan Engineering Works’, ‘Manhattan District’ and the “Manhattan Project” quickly became synonymous with state secrets, big science, nuclear energy and atomic annihilation.5

In that terrible flash 10,000 miles away, men here have seen not only thefate of Japan, but have glimpsed the future of America.

-James Reston, New York Times, 12 Aug 1945

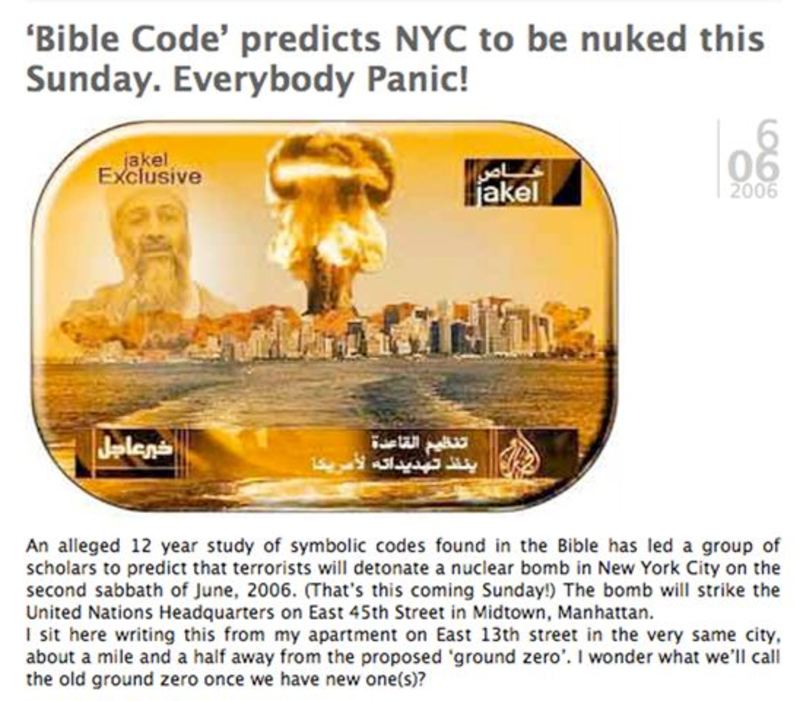

One of many post 9/11 blogs evoking nuclear terrorism. |

From the day of the atom bombing of Hiroshima, paradoxically, imagery of a nuclear attack on New York City became ubiquitous. It is and remains abundant in print, radio, music, movies, television programs, interactive video, computer and console games, internet sites and online blogs. The earliest image in our curated exhibition, Nuke York, New York, comes from a newspaper published on August 7, 1945, immediately after the first atomic strike. The most recent comes from post 9/11 websites that predict a terrorist executed “American Hiroshima.”

Our curated exhibition offers a wide sample of media and imagery produced over the past decades and each item serves to reflect the zeitgeist in which they were produced. Some are overtly political, some intend to effect shock or ridicule, some to entertain, and some to educate.

A leitmotif of American popular culture of the past two hundred years hasbeen the imagination of New York’s destruction […] No city has been moreoften destroyed on paper, film, or canvas, and no city’s destruction hasbeen more often watched and read about than New York’s.

-Max Page, The City’s End, 2008

Early Cold War depictions typically presented the vast scale of destruction if New York City was attacked with atomic weapons of the era. The Soviet explosion of a nuclear device in August 1949 resulted in an avalanche of such imagery evoking imagined attacks on the United States, often centered on NYC, the financial and cultural heart of the USA. Mainstream Hollywood films, for example, began depicting a nuclear war and a devastated New York as a fait accompli.6 Graphic magazine illustrations in Life, Colliers, ReadersDigest and Popular Mechanics, as well as lurid comic book artwork, frequently displayed nuclear cataclysm befalling the Big Apple.

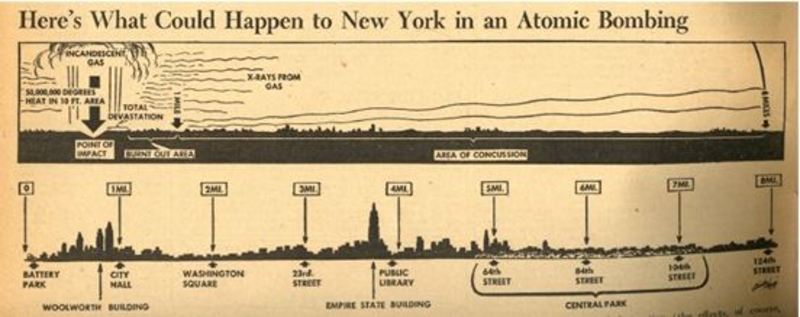

New York daily newspaper PM, 7 August 1945. |

As the American and Soviet arsenals grew, and the scale of nuclear weaponry and the reach of delivery systems increased (from A to H bombs, from bombers to ICBMs and from nuclear submarines to MIRVs), the depictions grew ever more dire. By the late Cold War many depictions assumed a camp or counter-culture sensibility often expressing derision or hostility towards American militarism.7

With the easing of superpower tensions in the post-Cold War era, the imagined nuclear aggressor increasingly became Arabic or Islamic terrorists, and as the enemy changed so too did the imagery, especially after 9/11. In computer games players can either fight, or become, invading armies or terrorists trying to nuke, or prevent disaster befalling, Manhattan. Recent network television programming depicts New York as falling victim to nuclear attack, often from ‘dirty bombs’ or ‘suitcase’ weapons. On websites warning of impending terrorist attacks on New York City one can detect enmity towards perceived “liberal elites” as well as patriotic fervor designed to stoke hostility towards America’s enemies.

“The Atomic Future” supplement, Chicago Sun, 3 May 1946. |

Expressing existential despair, patriotic fervor, technological fetishism, defrayed guilt, or apocalyptic voyeurism, depictions of a nuclear attack on New York City are as emblematic of the atomic age in the United States as is the mushroom cloud. We encourage visitors to NukeYork, New York to consider this sample of images from the Cold War, and beyond, and to draw their own conclusions.

|

Newspapers

The first images depicting a nuclear attack on New York City were published in newspapers to provide a reference so readers could grasp the scale of

destruction from the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These images appeared as early as the first edition after the bombing of Hiroshima on August 7th. PM, an evening newspaper published the first image of a nuclear attack on New York City on August 7th. The theoretical bomb was detonated above City Hall and the map of New York City below it showed areas labelled, “point of impact” “total devastation” “burnt out area” “area of concussion” and a vague area filled with “x-rays from gas.”8 Many of the same print motifs that had been so striking in describing the destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were far more grim when turned back to measure the potential impact of an enemy nuclear weapon on American cities: the concentric circles of destruction, the skyline measuring distances of impact.

Early Cold War depictions typically showed maps of NYC with indexes of corresponding destruction. Sometimes they showed graphics of the silhouetted Manhattan skyline showing the reach of detonations from strategic “ground zeros” such as the Empire State Building. These depictions served to educate the public about the scale of destruction of largely unimaginable weapons using a familiar and understandable model. Such depictions also functioned to shift the perception of the United States to that of potential victim of nuclear attack rather than the perpetrator of an actual nuclear attack.9 These fictional representations reveal an almost instantaneous sense of the vulnerability of Americans to nuclear weapons at a time when sole possession of nukes would be assumed to reassure American feelings of superiority and invulnerability.

In the late cold war the New York Post devoted an entire parody issue to fears of World War III and the obliteration of New York in a nuclear war. This November 1984 lampoon edition, including announcement of a 5,000-page obit section, belittled many Manhattan institutions, from Mayor Koch to the United Nations, while satirizing the real effects of such an attack.

“By the marble lions of New York’s Public Library U.S. technicians test the rubble of the shattered city for radioactivity,” Life 19 November 1945. |

In 2004 a New York Times op-ed titled “American Hiroshima” by Nicholas Kristof warned that, “If a 10-kiloton nuclear weapon, a midget even smaller than the one that destroyed Hiroshima, exploded in Times Square, the fireball would reach tens of millions of degrees Fahrenheit. It would vaporize or destroy the theatre district, Madison Square Garden, the Empire State Building, Grand Central Terminal and Carnegie Hall (along with me and my building). The blast would partly destroy a much larger area, including the United Nations.

On a weekday some 500,000 people would be killed.”10

Magazines

In the wake of Hiroshima, American magazines rushed to fill the gaps in public understanding about the new atomic weapons. Much like newspaper articles that detailed the destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, magazines made use of their readers’ familiarity with the size, landmarks and relative distances in New York City in order to describe the damage. A November 1945 article in Life magazine titled “The 36 Hour War,” was the first of what would be many articles to use the location of the New York Public Library in an illustration of the damage done by a nuclear attack on New York City.11 In a Mechanics Illustrated article in 1946 we see the use of the ubiquitous concentric circles of destruction superimposed over a map of Manhattan.12 That same year Fortune magazine published a fictionalized account of a nuclear attack on US cities (including NYC) titled “Pilot Lights of the Apocalypse,” invoking biblical images of the end of the world.13 A 1946 Reader’s Digest article titled “What the Atom Bomb Would Do to Us,” invited readers to imagine what would happen if an atomic bomb was dropped directly onto the Empire State Building.14 To help readers understand “What the Atomic Bomb Really Did,” Collier’s magazine published an article in 1946 that describes the scale of destruction “if an A-bomb blasted New York.”15 The avenues of devastation are meticulously listed followed by the explanation that “the economic heart of the nation beats in that area.”

Illustration by Chesley Bonestell, “Hiroshima U.S.A.” Colliers, 5 August 1950. |

After the Soviet Union got the bomb in 1949 some American magazines further imagined New York City as victim to an enemy bomb. In 1950 Collier’s magazine published an article titled “Hiroshima U.S.A.” accompanied by several original paintings by Chesley Bonestell that envisioned New York City being attacked by multiple nuclear weapons.16 Many similar stories were accompanied by images of the New York Public Library, the Empire State Building, or the Bro

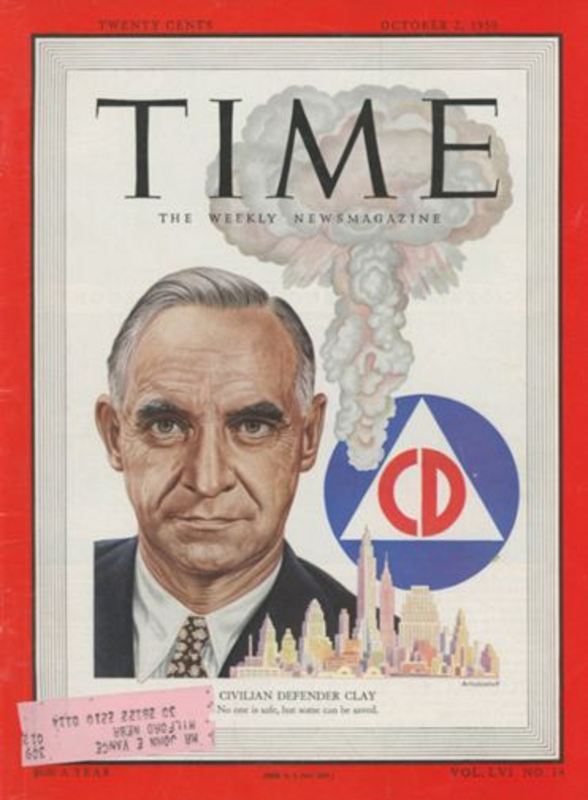

oklyn Bridge melting into a nuclear cauldron. These paintings relied on iconic buildings, cityscapes, and the shape of Manhattan Island itself to trigger fear at the destruction of such familiar architectures and landscapes. In October of 1950 Time magazine put Lucius Clay the Chairman of the New York State Civil Defense Commission on its front cover superimposed on an image of a mushroom cloud rising over the Empire State Building.17

|

In 1955, images of New York City with a mushroom cloud superimposed over it, even found their way into military magazines. A story in The Army Combat Forces Journal described the civil defense task of the armed forces and advocated stationing sufficient military forces near large urban centers to assist in recovery from atomic attack.18 These images, and the stories of attacks on New York City were part of a psychological shift in which Hiroshima, the nuclear victim, moved from being an enemy target attacked by the United States, to a nickname for America itself, the potential nuclear victim of the emerging Cold War.19 Labeling a New York City full of mushroom clouds “Hiroshima USA” was an expression of a deep sense of vulnerability to the new Soviet weapons.

Books

1945 and 1946 saw a flood of books about the atomic bomb and the nuclear future in American stores. Among these early works was an influential collection of writing by Manhattan Project scientists called One World or None (1946).20 The first chapter of the book, written by physicist Philip Morrison and titled “If the Bomb Gets Out of Hand,” describes a Hiroshima sized bomb being detonated above Manhattan: “Evidently there had been no special target chosen, just Manhattan and its people.” Morrison wrote that, “the streets and buildings of Hiroshima are unfamiliar to Americans,” and so he set his description somewhere more familiar to Americans readers. Morrison’s logic would be followed by dozens of other writers and artists who would choose to depict nuclear explosions in New York City to invoke its familiarity to Americans. Physicist Ralph Lapp wrote of Americans in his 1949 book Must We Hide? that “one person in twenty lives in New York City.”21 Lapp advocated dispersing both population and industry from urban centers in order for the United States to survive atomic attack.

“At the moment that we hear the shriek of the melting telephone in Moscow, I will order a SAC squadron which is at this moment flying over New York City to drop four 20-megaton bombs in precisely the pattern and altitude in which our planes have been ordered to bomb Moscow. They will use the Empire State Building for ground zero.”

-The President of the United States, Fail-Safe, 196222

|

|

Political thrillers often positioned New York City like a piece on a giant chess board of Cold War politics. In Fail-Safe (1962) the President of the United States agrees to bomb New York City with American nuclear weapons after an accidental American bombing of Moscow, as a means to avert a larger crisis and more destructive nuclear escalation.23Thirty Seconds Over New York (1970), riffing on the 1944 Spencer Tracy film Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, depicts the detonation of a nuclear weapon over New York City by terrorists from communist China. Stories of the Cold War turning hot were stories of cities being attacked.24

New York City provided the perfect backdrop to stories of the destruction of cities and of human society. When well-known buildings are seen tossed about or dissolved by nuclear explosions, when the iconic skyline of New York City is seen to be the front line of the Cold War, all of America feels at risk. Few Were Left (1955) told the story of a small number of people, maybe the last people left alive, who were trapped in a New York City subway after a sudden unknown event.25 In Shadow on the Hearth (1950) Judith Merril shows the deterioration of the well being of families in the New York suburbs after the city is attacked and the father doesn’t return.26 Images of survivors of nuclear war crawling out of the rubble of New York City were images of Americans everywhere imaging themselves crawling out into the rubble of modern technological society.

Post 9/11 America saw a resurgence of interest in novels of nuclear attacks on the United States. This new wave of books relocates the threat to America to Islamic fundamentalism, and portrays a nuclear attack on New York City and the United States as fulfillment of biblical prophecy. In 2005 the novel The Nuclear Suitcase a terrorist attack on New York City uses a nuclear suitcase manufactured during the Cold War in the former Soviet Union, and purchased on the black market by jihadists.27 The King of Bombs, published the same year and with an image of Osama bin Laden in the mushroom cloud over New York City on the cover, imagines the downfall of the United States after an Al Qaeda detonation of an H-bomb in New York City.28 Behold, an Ashen Horse published in 2007 imagines a nuclear attack on five American cities, including NYC, as Islamic jihadist act as agents of an apocalypse straight out of Christian eschatology.29

Wire photo of anti-nuclear weapons protesters outside the United Nations Building, 1958. |

Protest

During the last few years New Yorkers have exhibited an attitude which might be called a ‘prime-target-fixation syndrome.’ This is an expression of apathy or fatalism often found among those who believe that their city or location would constitute a prime target in the event of a nuclear attack.

-Herman Kahn, Hudson Institute, July 18, 1964

Throughout the cold war policies of “massive retaliation” or “mutual assured destruction” acknowledged implicitly that New York City would be a prime target in any nuclear exchange. Total war in the atomic age would bring annihilation to civilian populations. By the late 1950s and early 1960s Manhattan was encircled by a ring of nuclear-tipped anti-ballistic defensive missiles such as Nike-Hercules stationed at batteries a few dozen miles from the metropolis.30

|

Some of the million+ anti-nuclear protesters in Central Park, 12 June 1982. |

At the same time President Eisenhower’s annual Operation Alert, nationwide defence drills from 1954-1962, met with growing alarm and drew increasing civil resistance. Campaigns by anti-nuclear activists led to popular, nonviolent protest. Pacifists Dorothy May of the Catholic Worker and Ralph DiGia of the War Resisters League were among the first to disobey a New York City law imposing one year in jail and/or $500 fine for non-participation in the Alert. Despite the draconian penalties, every year more protesters gathered, and progressive women with children assembled in defiance of authorities. By 1960 the young mothers group had drawn support from cultural commentators such as Norman Mailer.31 In 1961 over 2,500 joined the protest outside City Hall that then spread to east coast campuses. Later that year, Dagmar Wilson of Women Strike for Peace inspired 50,000 women in New York and 60 other U.S. cities to protest ongoing nuclear testing. Operation Alert was cancelled permanently the next year.

After the cessation of atmospheric tests in 1963 and the negotiation of the first arms limitations treaties in the 1970s, mainstream nuclear fears re-emerged late in the cold war.

|

With over 70,000 nuclear weapons globally, many on hair-trigger alert, strategic rhetoric turned towards “first-strike” and fighting a “winnable,” “limited nuclear war.” However, when scientists calculated in the early 1980s that global extermination would occur from a ‘nuclear winter’ after even a “limited” exchange of weapons, the notion of “prevailing” became deeply contested. Around the world millions marched in protest against the renewed arms race. On 12 June 1982 in New York over a million people gathered in Central Park to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the city’s largest single gathering of citizens and the biggest protest in U.S. history, dwarfing the massive No Nukes demonstration against nuclear energy in New York a year earlier.

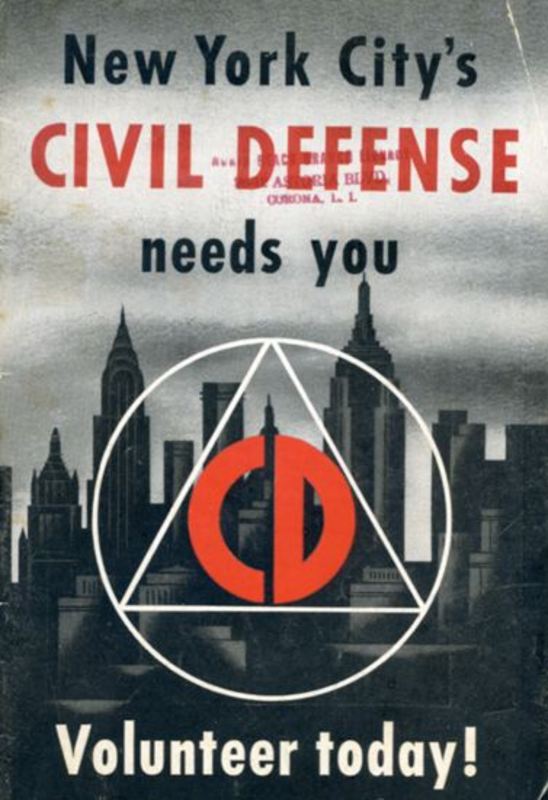

Civil Defense

The Federal Civil Defense Administration became a significant part of how Americans interpreted the nuclear threat after the acquisition of nuclear weapons by the Soviet Union in the fall of 1949.32 The first civil defense booklet printed, Survival Under Atomic Attack, was mailed to over 10 million American households in 1950.33 While this booklet didn’t include specific references to New York City, many pamphlets and booklets published in 1950 and throughout the rest of the Cold War did frequently refer to it. Some of these were printed and distributed directly by the federal government while others were reprinted and distributed by private businesses.

Sometimes the pamphlets used Manhattan as a reference point to understand the impact of nuclear weapons, and sometimes the city was used to represent everytown USA. Atomic Bombing: How to Protect Yourself, an official booklet printed by the government in 1950, presented New York City as America’s hometown.34 Imagining a future war in which nuclear weapons were launched at America with rockets, the pamphlet portrayed a missile exploding over Manhattan Island with the familiar Manhattan skyline and Brooklyn Bridge described as “your town.” The 1955 booklet Facts About the H-Bomb published by the U.S. government, the New York City skyline is used as a scale to understand the width of the fireball from the Mike thermonuclear test conducted in 1952 in the Marshall Islands.35

|

Mushroom clouds superimposed over images of New York City frequently graced the covers of civil defense pamphlets. In 1950 both the booklet You Can Survive Tomorrow’s Atomic Attack and The Atom Bomb and Your Survival portrayed mushroom clouds over graphic depictions of New York City with many of the buildings and surrounding areas in flames.36 The booklet Live: A Handbook for Nuclear Survival (1962) showed the Manhattan skyline having experienced nuclear attack and significant fallout danger, with New Yorkers safely protected in a personal family fallout shelter underground.37

|

The Federal Civil Defense Administration had offices in every state and major city. The tri-state area had many civil defense offices charged with preparing the population to survive an atomic attack. Civil defense offices issued book covers to school children, stockpiled toe tags to mark corpses after a nuclear attack and stockpiled large quantities of food and other supplies for use after a nuclear attack. In 2006 workers upgrading the structural integrity of the Brooklyn Bridge found a cache of 350,000 boxes of food, blankets and other supplies that had been stashed in a room in the foundation of the bridge, to be used to feed and comfort New Yorkers after a large scale nuclear attack.38

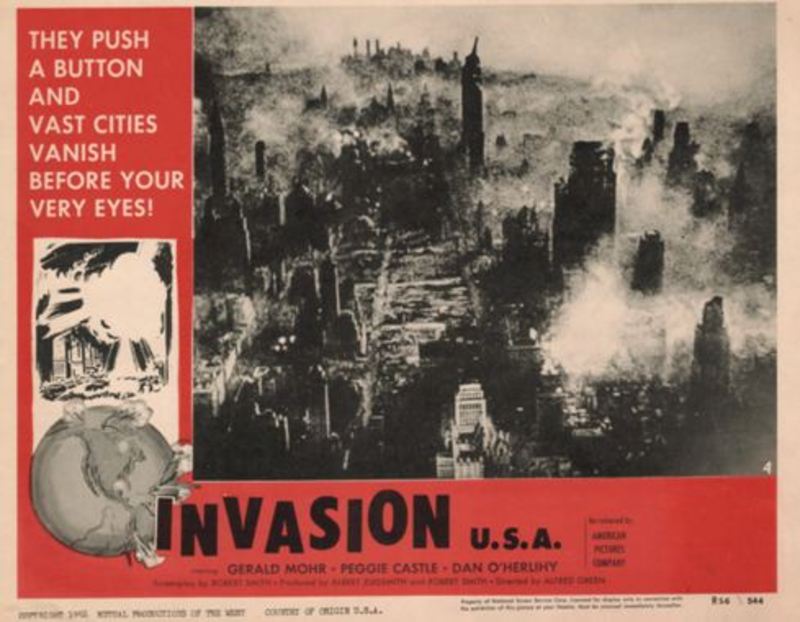

Film

Within a year of the Soviet A-bomb, Hollywood produced features reflecting fears of a catastrophic war. The now familiar trope of the deserted metropolis and a small band of survivors was a novel premise back in 1951 when Arch Oboler’s post-holocaust Five depicted a former Empire State barker describing New York’s destruction. By the end of the decade The World, The Flesh, and the Devil (1958) portrayed a trio of survivors wandering the deserted, but undamaged, Manhattan. In the cold war comedy The Mouse that Roared a tiny European principality “invades” New York during a citywide nuclear alert exercise and acquires a revolutionary Q-bomb, holding America ransom.39

A production still from Captive Women (RKO, 1952). |

The Planet of the Apes, 1968 |

Nuclear war or an imminent attack against New York was featured in the stridently anti-communist Invasion U.S.A. (1953) where patrons of a downtown bar are led to believe they are experiencing an all-out nuclear attack on America, including the A-bombing of Manhattan. With the ICBM launch of Soviet satellite Sputnik, American filmmakers responded to the dread of a potential missile war with Rocket Attack U.S.A. (1961) a low budget production that concludes with an American spy desperately trying to halt the launch of a nuclear missile against New York. Based on a best-selling novel, the film adaptation of Fail-Safe (1964) showed with forensic detail how an accidental nuclear war might occur, where the U.S. President sacrifices New York City immediately after Moscow has been destroyed in error.

A future, post-holocaust New York was envisioned as early as 1951 in Captive Women, set in the skeletal remains of Manhattan a thousand years after an atomic war, now populated by three tribes: the war-like Upriver People, the Mutates, and the Norms. New York’s annihilation was powerfully evoked at the finale of The Planet of the Apes (1968), where the iconic Statue of Liberty is discovered half-buried on a beach. The sequel, Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1971), continues the theme, revealing an advanced society of mutant humans living in New York’s devastated, subterranean remains. By the late cold war, a subgenre of low budget, post-punk European exploitation films depicted life after a nuclear war in New York, such as Endgame – Bronx lotta finale (1983) and 2019: After the fall of New York (1984).

Promotional artwork for The Divide, 2011. |

Film allegories of nuclear strikes on New York date back to The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) where a dinosaur, re-awakened by an American atomic test, ravages downtown Manhattan. The film inspired Japanese filmmakers to create Godzilla and, in Destroy All Monsters (1970), Godzilla emerges from the Atlantic Ocean to attack New York, destroying the U.N. building. The American remake of Godzilla (1998) also features the giant irradiated dinosaur, spawned from Pacific nuclear testing, devastating Manhattan.

Before the September 11 Al-Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the first Dreamworks movie, The Peacemaker (1997), depicted a White House nuclear analyst and special forces officer narrowly averting a Balkan terrorist nuclear blast in lower Manhattan. They prevent the device from going critical, but nevertheless it detonates as a “dirty” bomb. In the comedy-drama Bad Company (2002) a CIA agent works with a novice to save New York City from an imminent nuclear terrorist act.40 Most recently The Divide (2011) depicts a group of survivors contaminated by fallout trying to survive in a basement shelter after Manhattan has been destroyed by nuclear missiles.

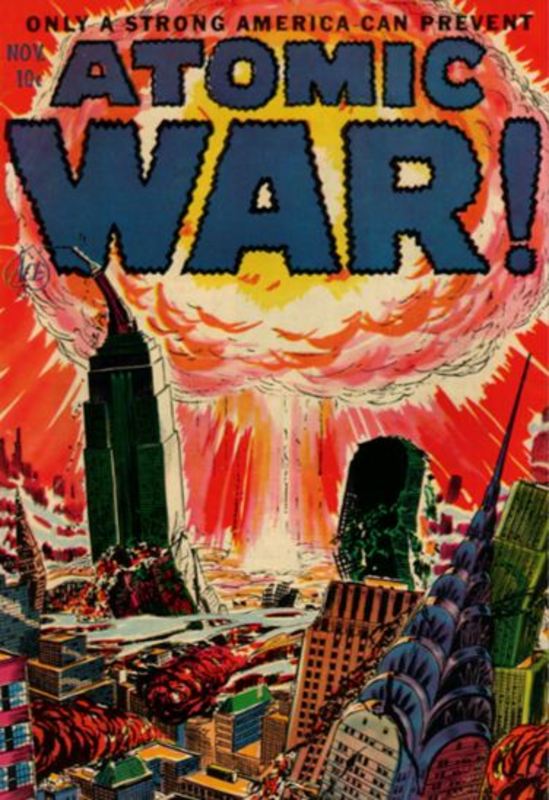

Comics

Before the Comic Book Code Authority was introduced in late 1954, artists and editors could create lurid and violent graphic works for children and teenagers without industry self-regulation. A few of these controversial comics directly addressed fears of a nuclear attack on New York. Perhaps the most arresting image was Al Feldstein’s January 1952 cover for EC’s Weird

Fantasy that depicts an incoming nuclear missile above a devastated Manhattan, with the Hudson River draining into a massive ground zero crater. Issues of Ace comics’ Atomic War! (1953-54) repeatedly depicted mass destruction with mushroom clouds towering above the New York skyline, or “to avenge what the Reds did to New York…”41

Atomic War! No.1, 1953 |

Weird Fantasy, No. 11, January 1952 |

Mighty Samson, No 2, June 1965 |

By the early to mid-1960s, comics increasingly adopted fantasies set in a post-holocaust world where nuclear war was a fait accompli long since passed. The serial adventure of the “Atomic Nights” ran in Strange Adventure comics from 1960-64 and featured a group of survivors, protected by radiation-resistant armour, exploring the post-nuclear remains of New York. Similarly, Gold Key’s popular Mighty Samson ran for 32 issues from 1964-82 portraying a partially blind, he-man mutant who scouts amongst the ruins of “N’Yark”, looking for atomic batteries and other pre-war goods. The cold war comic construct of an inevitable nuclear holocaust destroying the Big Apple remained resilient throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Like Mighty Samson, Kamandi “the last boy on Earth” is set in a partly flooded future New York. During these decades of détente, a battered and submerged Statue of Liberty frequently featured on comic covers to iconically convey a future atomic war, evident in Doomsday + 1, and The Planet of the Apes series. Marvel’s Godzilla, King of the Monsters also appeared across 24 issues, portraying the monster attacking New York with his fiery, nuclear breath.

A mutant toys with the idea of destroying Manhattan in Heroes, using the nuclear force literally in the palms of his hands. |

After 9/11 several comics concerned a post-nuclear Manhattan, some adopting postmodern irony, as in the From the Ashes “speculative memoir.” Others imagined scenarios in parallel or alternative universes, such as Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Dark Horse publishing’s Zero Killer, both series retrospectively set in “other” New Yorks of the 1980s and 1990s.

Television

Television programming has entertained similar disaster scenarios. In 1950, the Motorola TV Hour broadcast Atomic Attack, based on Judith Merill’s Shadow on the Hearth, featuring a suburban New York housewife learning that Manhattan has been obliterated.

|

While simulating a nuclear attack against New York, Edward Murrow’s advocacy documentary One Plane, One Bomb (1953) calls for civilians to volunteer as aircraft spotters. Throughout the 1950s newsreels and live TV broadcasts of the annual Operation Alert civil defence exercises regularly showed preparations for an attack by “five or more H-bombs” on Manhattan. Testimonial TV advertisements by real New Yorkers encouraged citizens to build their own bomb shelters and were funded by local civil defence authorities.

In The Twilight Zone episode “One More Pallbearer” (January 1962) a millionaire constructs an elab

orate bomb shelter under a Manhattan skyscraper but is driven insane, acting out his fears in an imagined missile strike.

With the end of the cold war, actor George Clooney nostalgically created a live television broadcast of Fail Safe (2000) screened in black and white and set like the novel in the early 1960s, culminating in the nuclear destruction of New York. Following the September 11 terrorist attacks, television programming returned to scenarios of nuclear disaster. In Jericho (2007), survivors in a small mid-west town piece together news of multiple nuclear explosions across America with New York City assumed to be among the targets. In Heroes (2006) a mutant artist with precognitive powers prophetically paints a nuclear explosion devastating New York City while another superhuman physically absorbs the ability to achieve critical mass. The episode, “Meditations in an Emergency” from Mad Men (2008) revisits the Cuban Missile Crisis and the preoccupation Madison Avenue advertising executives have with nuclear war. Preventing the terrorist use of “dirty” nuclear bombs in New York remains prominent in television scenarios, including the two-part episodes “Set Up” and “Countdown” of Castle (2011), and through much of the final series of 24 (2010), where CTU agent Jack Bauer races to prevent an Islamist strike against Manhattan using stolen nuclear fuel rods.

Games

In a pre-9/11 version of Flight Simulator for the personal computer, a Soviet FSX TU-95 could be modified to enable a player to fly over New York and drop two nuclear bombs. For the Play Station console PS2, Sony’s Godzilla Unleashed (2007), encouraged gamers to select various international cities, including New York, and battle kaiju ega foes (movie monsters) from the film series and do battle across a recognisable cityscape, using Godzilla’s radioactive breath and dinosaur tail to level skyscrapers and bridges such as the Empire State, Chrysler and Met Life buildings. The PC game World In Conflict (2008) featured an elaborate attack on Manhattan by Russian forces who storm the city. Gamers could target the Statue of Liberty for nuclear annihilation and watch an incoming missile obliterate the icon, and then pan about in real time to view its destruction from multiple angles.

Flight Simulator detonating two H-bombs over Manhattan. |

DEFCON 4 enables players to simulate a nuclear attack on the U.S. |

Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Double Agent (2006). |

A number of computer strategy games, such as Cuban Missile Crisis (2004) and Nuclear Strike (1997) rendered their imagined World War III to include strikes against New York. In DEFCON 4 (2006) multiple scenarios can be modelled to include attacks on Manhattan from submarine ballistic missiles, ICBMs and bombers, each registered on a geographical War-Room style chart, where detonations are accompanied by statistics such as “New York hit 10.6 million dead.” Other games create parallel or alternate histories to narratives and game play. In the first-person shooter X-Box 360 game Turning Point: Fall of Liberty (2009) the Nazis have won World War II and your mission is to prevent a Zeppelin from exploding an atomic weapon over New York in 1953.

A chilling cut scene informs the FPS game Splinter Cell: Double Agent (2006). If the player fails in the attempt to thwart a terrorist plot, downtown Manhattan is shown vaporised in a mushroom cloud, with the smouldering ruins then viewed from the air. In contrast, expert gamers could also modify (mod) narratives and action to create their own “prod-user” content, such as a popular mod of Grand Theft Auto 4 (2008), uploaded to YouTube, where the criminal protagonist calls in a nuclear hit on New York from his cell phone, shown from atop a skyscraper, which blasts him off the roof.

Online

When Nicholas Kristof wrote his “American Hiroshima” op-ed he was merely bringing into mainstream visibility a right-wing cultural meme that had been festering on the internet since the 9/11 attacks in 2001.42

|

Survivalist online communities had long been abuzz with stories of an imagined “American Hiroshima” being planned by Osama bin Laden that would target many American cities. However, as well as expressing their fears, such fantasies allowed them also to imagine their domestic enemies perishing. In these depictions of terrorist attacks on New York City one can detect hostility towards perceived “liberal elites” as well as patriotic fervor designed to stoke hostility towards America’s enemies.

One website offered the following declaration alongside an image of a mushroom cloud photoshopped onto a picture of the New York City skyline, “There is no question, based on captured documents and captured al-Qaida leaders that Osama bin Laden has been planning his “American Hiroshima” for many years—long before Sept. 11, 2001.”43

|

Another website claims that, “Al-Qaida is now putting out the word that they want to create an American Hiroshima. Then, while the entire country scrambles in reaction to the first bomb going off, a second one goes off a few days later—just like Nagasaki. In order to make this continue to appear like a religious war the proposed plan is to attack US cities with large Jewish populations (i.e. New York, Chicago, Miami, D.C, & Las Vegas).”44

These images present a postmodern, online, crudely photoshopped vision of American vulnerability. However they also present a voyeuristic fantasy about the incineration of imagined “east coast” elites and ethnic minorities.

Since 9/11 many videos have appeared on YouTube that depict a nuclear explosion on New York City. Some of these are crude attempts to create compelling video effects by people working with video software programs, but many are further fantasizing about the dangers of imagined attacks by jihadists and the imagined annihilation of multi-ethnic American urban centers. Additionally, many survivalist websites began to provide online “Ground Zero calculators” which would allow visitors to estimate the extent of the effects from imagined nuclear attacks on American cities.45 These sites allow the viewer to enter the location and size of the bomb and the local weather conditions and view maps with concentric circles of destruction and fallout plumes, allowing visitors to personalize the illustrations of the Cold War era in which readers were collectively presented with such images in newspapers or magazines.

Conclusion

|

It is clear from the diversity and longevity of these cultural manifestations, both state sanctioned and independent, that an “American Hiroshima” emphasizing New York City as the locus for an “inevitable” nuclear attack has penetrated deep into the American psyche. Justifying heightened national security measures at the expense of civil liberties, senior staff in the Bush Administration’s Defense and State Departments publicly foregrounded such an attack, not as an “if,” but as a “when.”46 Adopting this prognosis as a policy fait accompli reinforces a complex and contradictory sense of guilt and betrayal, where U.S. culture perversely projects a preemptive sense of outrage as a nuclear victim, not a nuclear perpetrator.

As Max Page has shown, New York City has long been emblematic of American progress, prestige and profit and regarded as a national and international site for both awe and envy. Visions of New York’s destruction resonate with “some of the most longstanding themes in American history”, where each generation finds reason to imagine the city’s end.47 This ambivalence towards the Big Apple also informs conflicting post 9/11 sentiments. Following Tom Engelhardt’s incisive work, Victory Culture, historian John W. Dower has argued powerfully in Cultures of War that the euphoria of victory over Japan was extraordinary, but also fragile and ephemeral.48 “The underside of triumph was profound anxiety—a presentiment that making and using the atomic bomb had birthed not peace but vulnerability of a sort inconceivable just a few years earlier […] When the twin towers of the World Trade Center were taken down on September 11, this suppressed or diluted dread erupted, certainly among Americans, as full-blown collective trauma.”49 In its assembly and display of a variety of mass mediated forms, our Nuke York, New York exhibition seeks to give witness to the lingering expression of these anxieties, from the atomic strikes against Japan in August 1945 to post 9/11 America.

Mick Broderick is Associate Professor and Research Coordinator in the School of Media, Communication & Culture at Murdoch University, where he is Deputy Director of the National Academy of Screen & Sound (NASS). Broderick’s scholarly writing has been translated into French, Italian and Japanese, and his major publications include editions of the reference work Nuclear Movies (1988, 1991) and, as editor, Hibakusha Cinema: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Nuclear Image in Japanese Film (1996, 1999). Recent co-edited collections include Interrogating Trauma: Arts & Media Responses to Collective Suffering (2011) and Trauma, Media, Art: New Perspectives (2010).

Robert Jacobs is an associate professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University. He is the author of The Dragon’s Tail: Americans Face the Atomic Age (2010), the editor of Filling the Hole in the Nuclear Future: Art and Popular Culture Respond to the Bomb (2010), and co-editor of Images of Rupture in Civilization Between East and West: The Iconography of Auschwitz and Hiroshima in Eastern European Arts and Media(2012-forthcoming). His book, The Dragon’s Tail,will be released in a Japanese language edition by Gaifu in April. He is the principal investigator of the Global Hibakusha Project.

Recommended citation: Mick Broderick and Robert Jacobs, ‘Nuke York, New York: Nuclear Holocaust in the American Imagination from Hiroshima to 9/11,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 11, No 6, March 12, 2012.

Notes

1 On transposing and conflating Hiroshima and “ground zero” with 9/11, see Antoine Bousquet, “Time zero: Hiroshima, September 11 and apocalyptic revelations in historical consciousness,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 34:3 (2006): 739-764, and Mick Broderick, “Waiting to Exhale: Somatic Responses to Place and the Genocidal Sublime,” IM: Interactive Media 4. (Summer 2008), here.

2 Robert Jay Lifton and Gregg Mitchell, Hiroshima in America: A half century of denial (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1995): xv.

3 Gary Andrew Poole, “On the West coast, a paranoid run on iodide pills,” Time (March 17, 2011): http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,2059408,00.html

Dennis Romero, “Japan Earthquake: Could nuclear power radiation reach LA?” LA Weekly (March 17, 2011): here; Mark Clayton, “Traces of Japanese radiation detected in 13 US states,” Christian Science Monitor (March 28, 2011): here.

4 link.

5 Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986).

6 See Mick Broderick, “Surviving Armageddon: Beyond the Imagination of Disaster,” Science Fiction Studies, 62, (1993): 362-382.

7 Jeff Nuttall, Bomb Culture (London: HarperCollins, 1970).

8 “Here’s what could happen to New York in an atomic bombing,” PM (August 7, 1945): 7.

9Robert Jacobs,”Reconstructing the perpetrator’s soul by reconstructing the victim’s body: The portrayal of the “Hiroshima Maidens” by the mainstream American media,” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 24 (June 2010): here.

10 Nicholas D. Kristof, “An American Hiroshima,” New York Times (August 11, 2004): here.

11 “The 36 hour war: The Arnold Report hints at the catastrophe of the next great conflict,” Life 19:21 (November 19, 1945): 27.

12 “Peace or else,” Mechanics Illustrated (February 1946).

13 Louis Ridenour and Louis Nicot, “Pilot lights of the apocalypse,” Fortune (January 1946): 13-15.

14 Robert Littell, “What the atom bomb would do to us,” Reader’s Digest (May 1946): 125.

15 Robert De Vore, “What the atomic bomb really did,” Collier’s 117:9 (March 2, 1946): 19.

16 John Lear, “Hiroshima U.S.A.: Can anything be done about it?” Collier’s (August 5, 1950): 11-15.

17 “Civilian Defender Clay,” Time (October 2, 1950).

18 “Another job for the Army,” Armed Combat Forces Journal 5:8 (March 1955): 32.

19 Robert Jacobs, “Domesticating Hiroshima: American Depictions of the Victims of the Hiroshima Bombings in the Early Cold War,” in Urs Heftrich, Bettina Kaibach, Robert Jacobs and Karoline Thaidigsmann, eds., Images of Rupture in Civilization Between East and West: The Iconography of Auschwitz and Hiroshima in Eastern European Arts and Media (Köln: Böhlau, 2012) forthcoming.

20 Dexter Masters and Katherine Way, eds., One World or None: A Report to the Public on the Full Meaning of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Federation of American Scientists, 1946).

21 Ralph E. Lapp, Must We Hide? (New York: Addison-Wesley Press, 1949): 141.

22 Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler, Fail-Safe (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962): 262.

23 Burdick and Wheeler, Fail-Safe (1962).

24 Robert Burchard, Thirty Seconds Over New York (New York: Morrow, 1970).

25 Harold Rein, Few Were Left (New York: John Day, 1955.

26 Judith Merril, Shadow on the Hearth (New York: Doubleday, 1950).

27 Henry Williams, The Nuclear Suitcase (Self-published: iUniverse, 2005).

28 Sheldon Filger, King of Bombs: A Novel About Nuclear Terrorism (Self-published: Authorhouse, 2005.

29 Lee Boyland, Behold an Ashen Horse (Self-published: Booklocker, 2007).

31 See “Operation Alert” here.

32 Robert Jacobs, “Survival of self and nation under atomic attack,” The Dragon’s Tail: Americans Face the Atomic Age (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010): 61-83.

33 Federal Civil Defense Administration, Survival Under Atomic Attack (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950).

34 Federal Civil Defense Administration, Atomic Bombing: How to Protect Yourself (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950).

35 Federal Civil Defense Adminstration, Facts About the H-Bomb (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1955).

36 Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Survive Tomorrow’s Atomic Attack (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950); Federal Civil Defense Administration, The Atom Bomb and Your Survival (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950).

37 Roger S. Cannell, Live: A Handbook for Nuclear Survival (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1962).

38 Sewell Chan, “Inside the Brooklyn Bridge, a whiff of the Cold War,” New York Times (March 21, 2006): here.

39 For a complete list, see Mick Broderick, Nuclear Movies (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1991).

40 Mick Broderick, “Is this the Sum of Our Fears? Nuclear Imagery in Post-Cold War Cinema,” in Scott C. Zeman & Michael A. Amundson, (eds) Atomic Culture (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2004): 127-149.

41 See Ferenc M. Szasz, “Atomic Comics,” in Scott C. Zeman & Michael A. Amundson, (eds) Atomic Culture (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2004).

42 Kristof.

43 “An American Hiroshima”: here.

44 Major Van Harl, American Hiroshima?: here.

45 Truth is Treason: here.

46 See “Terrorist nukes are ‘inevitable,’ Rumsfeld says“, London Free Press (Canada), here.

47 Max Page: 4.

48 Tom Engelhardt, The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation, (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008).

49 John W. Dower, Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9-11, Iraq, (New York: Norton, 2010): 224.