On ひろしま hiroshima: Photographer Ishiuchi Miyako and John O’Brian in Conversation

John O’Brian

Introduction

Installation Shot. Photograph by Viktor Munhoz |

In the fall of 2010, Linda Hoaglund visited British Columbia to screen her film ANPO: Art X War at the Vancouver International Film Festival. The documentary peels back the layers of deceit and controversy surrounding the renewal of the 1960 treaty that allowed the United States to continue operating close to 100 military bases in Japan. The photographer Ishiuchi Miyako, who grew up in Yokosuka, a port city near Yokohama where her mother drove a jeep at the U.S. navy base, has a major part in the film. The revelations in ANPO struck a sharp chord with audiences in Vancouver. The force of the film quickly led to conversations between Linda Hoaglund, Satoko Oka Norimatsu and Tama Copithorne. Acting on behalf of Ishiuchi, Hoaglund explained that she wanted to arrange an exhibition of the artist’s Hiroshima photographs in Vancouver – and to make the exhibition and its reception the centerpiece of a new documentary film she was directing on Ishiuchi. Anthony Shelton, director of the UBC Museum of Anthropology, agreed to mount the exhibition, Karen Duffek, curator, undertook its organization, and Hoaglund was present at the opening with a Japanese film crew.

ひろしま Hiroshima ran in Vancouver from October 13, 2011, until February 12, 2012. A diverse series of public programs was organized to accompany the exhibition by the museum in conjunction with Tama Copithorne. The Vancouver Chamber Choir performed Requiem for Peace: Reflections of Hiroshima by Larry Nickel, the Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (Centre A) organized a conference on Arts of Conscience: From Hiroshima to Vancouver, and the Bunkaza Theatre Company from Tokyo performed One Thousand Cranes by Ren Hisa, based on the original play by Colin Thomas. There were also illustrated talks, dance performances, film screenings and more. The exhibition and the programming generated an extended conversation in Vancouver about nuclear threat and catastrophe.

Museum of Anthropology. Photograph by Bill McLennan |

On August 4, 2011, two months before the exhibition opened, Ishiuchi Miyako and I taped a conversation in the Great Hall of the Museum of Anthropology, for which Linda Hoaglund acted as translator.

I began the conversation by talking about the city of Vancouver and Canadian nuclear policy, with the idea of providing a context for viewers of her work in this region. Her Hiroshima photographs have been exhibited in half-a-dozen venues in Japan, but they have not been shown previously in North America. I offered two major reasons why I think that Vancouver is an appropriate city for the work to be seen. One is a social reason: Vancouver is a city that once had a large Japanese population. Before being interned following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, 22,000 Japanese Canadians lived on the coast, and following the war were not permitted to return. The second reason is art related. Over the past 30 years, Vancouver has become a major center for producing and thinking about photography. One of the important early figures was the artist Roy Kiyooka, a Nisei, who moved to the city in the 1960s.

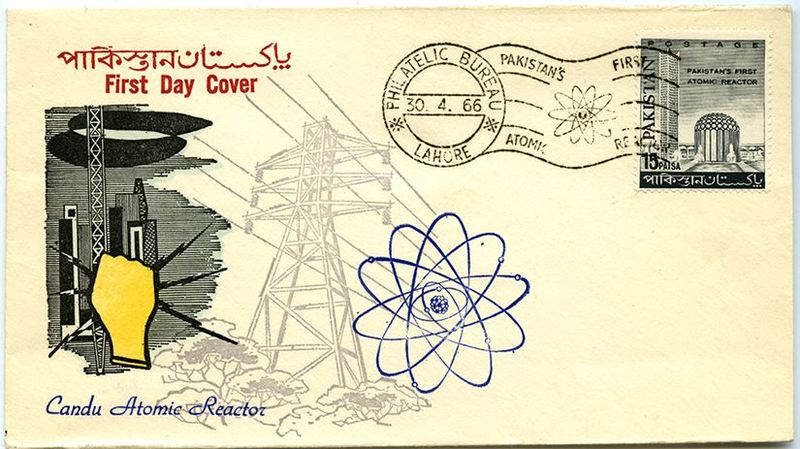

CANDU Reactor, Trombay, India, 1960 |

Canada generally thinks of itself, and is known in some international quarters, as a peacekeeping nation that has distanced itself from nuclear arms. The nation is smug about this reputation. In order to maintain the fiction of an anti-nuclear position, however, the country has had to disavow a significant part of its military and atomic history. Not only has Canada been at war for the past decade, but it was also a significant partner in the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb. One of its contributions was to supply the uranium for the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

At the end of World War II, Canada was one of three atomic powers in the world. Had it wished to build its own nuclear arsenal, it possessed the necessary scientific expertise and material resources to do so. The government opted against the pursuit of a nuclear weapons program, choosing instead to steer a wobbly course between building and banishing the bomb. Canada continued to produce uranium, selling it to the United States and Britain for nuclear weapons, and through long-term agreements turned over its coastlines and landmass to the United States for use as proving grounds for nuclear missile and submarine testing. It also accepted American nuclear-tipped Bomarc missiles on Canadian soil, and exported Canadian nuclear expertise around the globe in the form of the CANDU reactor. Canadian CANDU reactors were sold to India, Pakistan, and China, among other countries.

The uranium for the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945 was mined near the Arctic Circle with the assistance of the Dene people. Nobody in the far north knew what the uranium was for. Even though the Dene, too, were unknowing about what they were helping to mine, they felt complicit about their role in producing the bomb. In 1998, a Dene delegation went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to apologize to the Hibakusha, the survivors of the bombing, for having mined the uranium used in the bombs.

Miners, Port Radium, 1946 |

I recently discovered another story that connects Vancouver with the history of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the bomb. It concerns a nuclear physicist, Shuichi Kusaka, who was born in Osaka in 1915 and soon afterwards came to live in Vancouver.

Shuichi Kusaka, 1943 |

He went to the University of British Columbia, where he studied theoretical physics and was a brilliant student, before continuing on to complete his PhD at Berkeley with Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb. He was refused permission to work on the Manhattan Project because he was Japanese, or thought to be Japanese, even though he was a Japanese-Canadian. Osaka University invited him to Japan as a professor in 1940, but he declined the offer. He went instead to work with Einstein at Princeton. He later drowned in a swimming accident, and now seems to be largely forgotten. He should be remembered, as should Canada’s engagement with nuclear fission.

Conversation

John O’Brian: It is privilege to have you here and to know that your exhibition of Hiroshima photographs is showing at this museum. Do you think that the photographs in your exhibition will speak to the totem poles, and that the totem poles will speak to your exhibition—that they’ll have a conversation?

Ishiuchi Miyako: Yes, of course. I’m confident they can have a conversation.

JO’B: I think so, too, and I want to know whether you think this is an important place for your photographs to be seen. Would it be just the same to you if the exhibition were in Boston, Kansas City, San Francisco, or Seattle? Or, do you think there’s something special about having it in Vancouver?

IM: It’s different for me because it’s Canada and not the USA. Of course, ultimately I do have a goal of wanting to show these photographs in the USA, but I think Canada is the perfect place to start.

JO’B: You are showing the work in an anthropology museum that has an international reputation for presenting artifacts, such as the totem poles now surrounding us, as art.

Great Hall, Museum of Anthropology. Photograph by Ema Peter |

Still, this is an anthropology museum. Visitors sometimes have different expectations of what they’re going to see, and different responses, than they would in an art gallery. Do those implications interest or bother you—or, possibly, excite you?

IM: Before coming here, I actually had some doubts about my work being shown in an anthropology museum. But being here, those doubts have gone. My photographs are like the totem poles: they are things that have been left behind, and they’re clearly going to be exhibited as art. The one concern that I openly shared and that I think we will solve is how to seduce the throngs of people that come to the Great Hall into the more subdued, darker space where the gallery showing my work resides.

Ishiuchi Miyako, ひろしま, #5, C-type print, 2007-2008 |

JO’B: It strikes me that the poles and your photographs are both quiet, in the sense that you can’t look at them quickly. They take time to look at, and that’s a strong connection.

IM: Until now, the only photographs we had of Hiroshima were either imbued with an intentional social meaning or they were documentary records of an historical event.

What I’ve done with my Hiroshima photographs is that I’ve pushed them much farther into art. And so, ironically, I feel that it is very appropriate for them to be shown here along with the totem poles.

JO’B: Perhaps that’s because there’s a tension between documentary and fine-art photographs.

There is always a little bit of documentary in the fine-art photograph and a little bit of art in the documentary image—in the same way that there’s art in these objects as well as in the artifacts of anthropology. There’s a productive tension. So I’m very interested in your answer. It recognizes that tension.

IM: You get it, don’t you?

JO’B: I’m trying! Now I want to ask some specific questions about the Hiroshima series of photographs. They were first shown in 2008 in the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. That museum has a long history of commissioning works of art that relate to the nuclear era: Yoko Ono, Henry Moore, Simon Starling, Muraoka Saburo. Were you commissioned by the museum?

Postcard of Aioi Bridge, Hiroshima, 1945.Hiroshima, 1945 |

IM: No, an editor at a publishing house who saw my work, Mother’s, approached me and said, “Could you please photograph Hiroshima for a book?”

I had never been in Hiroshima in my life, and I knew that it had already been photographed by so many photographers. I really anguished over whether it was appropriate for me to take photographs of Hiroshima. And then it was very important to me that my Hiroshima photographs start their way into the world in Hiroshima, so that I could gauge the temperature of the local people’s reaction.

JO’B: Do you think that your photographs bring the past into the present? Or do you think it’s possible that they reverberate between the past and the present—that they move back and forth?

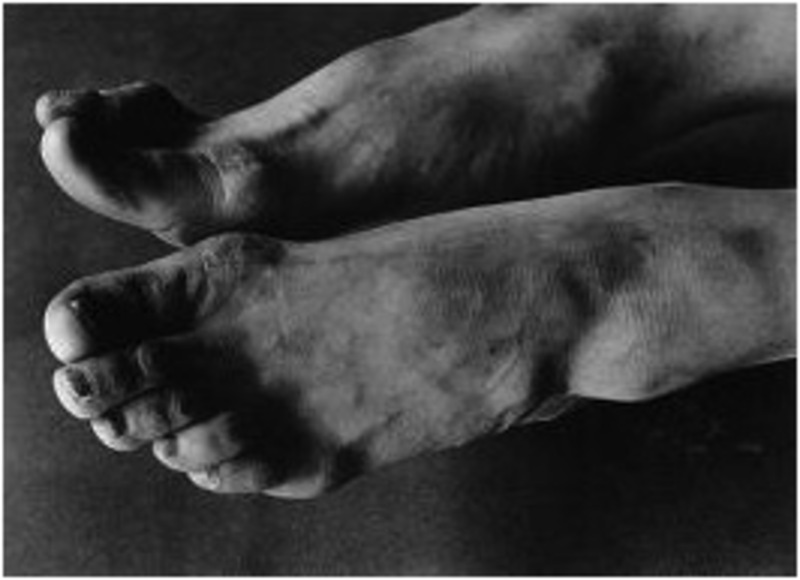

Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s, #63, silver gelatin print, 2000 |

IM: I can’t photograph the past, but what I can do is photograph the present. It’s up to the viewer to bring to my images of the present whatever memories they want. In Japan—especially in Japan—Hiroshima is so catastrophic that there’s a kind of taboo about having any kind of intimate or personal reaction to it. It’s always supposed to be something bigger, something overwhelming. But for me, all I’ve done is record my personal, individual reaction in those photographs. If I had been a young woman there, 66 years ago, I might have worn that dress, or I might have been in that skirt that day. That’s the way I see those images. That’s the way I see those objects.

JO’B: The Hiroshima photographs have a kinship with your Mother’s series that was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2005. I did not see the Biennale that year, which was my loss, but I did see a selection of photographs from the series at the International Center of Photography, New York, in 2009. That was my first encounter with your work, and I had a chance to look at the photographs carefully.

Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s, #52, C-type print, 2003 |

By the time the series was finished, you have written, “My Mother’s series, consisting of personal items left by my late mother, had established itself as a distinct body of work and had lost its private connotations.”

IM: I wrote about what I experienced: that by exhibiting my Mother’s series in Venice, my mother moved on. She left me behind, and she became art; she stopped being my private mother and became everyone’s mother. I saw so many women in the exhibition hall crying at my photographs, and that’s when I realized that she wasn’t mine anymore. She belonged to everyone.

JO’B: In Mother’s would you consider yourself a “portraitist”—a portraitist of someone who is no longer alive?

IM: Portraits. Yes.

JO’B: The photographs seem to distance the presence of your mother at the same time that they assert her trace. This is an interesting paradox. How do you explain it?

IM: It’s very difficult for me to take pictures from the perspective of the viewer. I can only be the one providing the photographs. This year for the first time I showed a small exhibit of Mother’s and Hiroshima photographs in southern Japan, and there was a man who was crying at one of the Mother’s photographs; he had just lost his wife. My photographs seem to emit meanings I never intended, and so they move away from me.

JO’B: Photographic historians and critics have observed that since the 1960s—since the Vietnam War and the development of the 24-hour news cycle—photography has been forced to develop new modes of practice. It is much more difficult to make convincing photographs of the kind produced by Yamahata Yosuke and Matsushige Yoshito in 1945.

Matsushige Yoshito, Hiroshima After 4.00 p.m., 5 August 1945 |

That kind of work continues, but it has lost a lot of its force. So, photography has entailed a retreat from documenting unfolding events. Photographic historians and critics have called this “late photography.” They are saying that instead of proximity, we now have distance. Instead of quick reactions, we have reflection. Instead of the jittery snapshot, we have the unhurried stare. Do you think that you have become a “late photographer” of this kind? Your early work wasn’t this way, but do you think that with Mother’s and Hiroshima, you’ve become that kind of photographer?

IM: I don’t think you can categorize my work that way. I have to say that whether it’s late photography or early photography, honestly all I do is capture what’s in front of my eyes. It’s extremely straightforward.

JO’B: That’s the answer of an artist! Refuse to be pigeonholed.

IM: Hiroshima had been pigeonholed. All those images of Hiroshima represented a pigeonhole that I am trying to break out of. Hiroshima has calcified into “History.” Hiroshima itself is much more free. I wanted to set it free, put it at ease, so that we can really look at what we’re seeing.

JO’B: There’s one other reason why you don’t fit comfortably into the “late photography” category. You continue to use a handheld, 35-mm camera without a tripod. When I saw the Mother’s photographs and then the Hiroshima photographs, I thought you were using a large-format camera on a tripod.

IM: No, it’s the only camera I own. I find tripods constricting.

JO’B: In recent decades, much photography in Vancouver has become highly deliberated, not only in conception but also in execution. Big cameras, tripods, choreographed lighting.

Ishiuchi Miyako, ひろしま, #82, C-type print, 2007-2009 |

IM: I want to take as few images as possible as quickly as possible. I don’t want to shoot a lot because I want to remember every object, every image. If I take too many, then I can’t memorize every image.

JO’B: Your images, when you print them and show them, are different sizes. Some are large, some quite small. And you install them at different levels on the wall. What is the aesthetic logic behind these decisions in presentation?

IM: To me, the exhibition space is an organic space. So I let my physical reaction guide me. I try to make the clothes as close to their real, actual size as possible. Shoes and gloves I tend to print smaller.

JO’B: In the Hiroshima series you photographed against the light—putting clothing on the light box—or with the light in terms of natural light flowing through the windows in the Hiroshima Peace Museum. Did you ever think that in the light box, with the light piercing through the clothing, there was a parallel to the flash of the atomic bomb?

IM: No, the light box was inspired by the way I photographed the Mother’s series, where I hung her personal effects onto the glass windows in her living room. But if you just do that, you can see the outside view through the window. So I put up tracing paper on the window and taped the objects onto it. The light box was just a bigger version of that. I couldn’t exactly start taping Hiroshima’s personal effects onto a window, so I had to create the light box.

Ishiuchi Miyako, ひろしま, #69, C-type print, 2007-2008 |

JO’B: What’s so interesting to me about your answer is that the how of making the photographs, which is what we’ve been talking about—the camera you use, the light box you use, the number of images your take, the size of the images you print—reflects the thinking behind the photographs. Always. The thinking reflects the how.

IM: I want to keep it simple.

JO’B: You are fusing the how with the what in the photographs. You try to keep it simple, but it involves a complex set of relationships. That is how good photographs get made.

IM: In turn, I actually want to ask you a question. What inspired you to think there might be a parallel, in my mind, between the light box and the atomic flash?

JO’B: At the heart of the atomic bomb is light, energy, power, heat. That is what damaged the clothing. You may not have been conscious of this, and it may just be my interpretation. I wouldn’t insist on the matter too hard, but I think there is a connection worth considering.

IM: All I can say to that is “thank you.” The light box is a man-made sun. I took a new man-made sun to Hiroshima. We can’t take photographs without the sun—without light.

JO’B: Do you think that objects, and then the representations of individual, personal objects—like those of your mother and the clothing you photographed—can tell stories? Audiences make stories from them. I don’t think that is necessarily your intention, but the work leaves a space for that to happen.

IM: Yes, yes.

JO’B: Your Hiroshima series strikes me as allegorical. The images represent themselves not as wholes but as fragments that need to be seen against the work of other representations of Hiroshima and nuclear catastrophe: for example, against the five photographs taken by Matsushige Yoshito on August 6, 1945, and those taken at Fukushima Daiichi earlier this year.

Fukushima Daiichi, Unit No. 4, February 2012. Photograph by Matsumura Akio |

Does allegory interest you? Do allegorical readings of your work seem justified?

IM: Yes, my Hiroshima photographs follow in the wake of the other photographers’ work. My photographs are connected with Matsushige’s.

JO’B: They also speak to Fukushima. By means of allegory, they relate to the meltdown. The photographs are part of a larger whole.

IM: Yes, because Fukushima is a very critical question for the world today, and for Japan. Obviously I had no such intention when I was taking the photographs, and my own approach to those photographs hasn’t changed. But clearly there is now a difference in the way people react to them—to the very same images. Honestly, what these events have taught me is that nothing has changed since the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. I, too, have remained ignorant of the extent of our dependence on nuclear energy and on the hazards of nuclear energy. And so my reaction is to say that nothing really has changed since 1945—and conversely, that it’s suddenly newly important to look at Hiroshima again.

Ishiuchi Miyako, ひろしま, #9, C-type print, 2007-2008 |

JO’B: Above all, to look more slowly. Your Hiroshima series encourages a different kind of viewing response than media images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki or of the meltdown at Fukushima. The series resists an instantaneous response from viewers, and instead encourages reflection and interpretation. The work strikes me as deeply evocative—an effect provoked by the sense of loss signaled by the remaining trace of clothing—and demands that viewers mull over what they are looking at.

John O’Brian is Professor of Art History at the University of British Columbia. He has published extensively on modern art history, theory, and criticism, and is currently researching the engagement of photography with the atomic era. His most recent book, co-authored with Jeremy Borsos, is Atomic Postcards: Radioactive Messages from the Cold War (Intellect Books, 2011).

Japanese-English translation of Ishiuchi Miyako’s words by Linda Hoaglund. Producer-Director Linda Hoaglund is working with Ishiuchi Miyako on a film, Things Left Behind, documenting her photography and the Museum of Anthropology exhibit in Vancouver.

http://www.thingsleftbehindfilm.com/

Recommended citation: Ishiuchi Miyako and John O’Brian, ‘On ひろしま hiroshima: Photographer Ishiuchi Miyako and John O’Brian in Conversation,‘ The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, issue 10, No 7, March 5, 2012.“