The Boat

Around 10pm on 5 October 1948 a small boat made its way along the coastline of Cape Sada Peninsula, the long finger of land that juts west from Ehime Prefecture on the Japanese island of Shikoku. The darkness was intense. It was a moonless autumn night, and the forested spine of hills above the jagged cliffs of the peninsula was devoid of lights.

|

Shikoku and the Tsushima Strait |

The boat – a 20-ton wooden vessel called the Hatsushima1 – had left the heavy swell of the open ocean and now moved slowly and quietly through the calmer waters of the Uwa Sea. No doubt the captain believed that his craft’s progress along this remote stretch of Shikoku coastline was unobserved. In the little fishing villages which dotted its rocky inlets the working day began and ended early, and most of the villagers were already asleep. But from the hills above, eyes were watching.

The people of Cape Sada Peninsula in October 1948 were still gradually recovering from the devastation of war. In the last months of the Pacific War the center of the nearest big city, Matsuyama, had been reduced to a burnt-out wasteland by allied fire-bombing.2 The villages had been spared the worst of the air-raids, but during the final stages of the war their fishing boats had been requisitioned by the military or lain idle, unable to venture out into the dangerous waters of war. Men who had been recruited to fight in China or Southeast Asia, and families who had migrated to Manchuria to help build Japan’s Greater East Asia Prosperity Sphere, were still trickling home, transformed by experiences which could seldom be put into words. Many would never return; many remained unaccounted for.

The end of the war had not meant the end of hardships for the people of Cape Sada, for the immediate postwar years had brought a series of disasters – typhoons followed most recently by flooding rains.3 Foreign troops from Britain and Australia now occupied their region, while in Tokyo the office of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), US General Douglas MacArthur, was issuing a bewildering stream of directives about economic and social reforms. But at least by the autumn of 1948 the threat of imminent death had retreated. A few goods were starting to appear in the shops; more were appearing in the black markets which had sprung up overnight around the railway stations of the region’s towns.

By 10.30, the Hatsushima had traveled almost the entire length of Cape Sada, and began to move silently towards the sheltered harbour of Kawanoishi at the eastern end of the Peninsula. The boat’s passengers must have sensed, from the calm of the water and quieter throb of the boat’s engine, that they were approaching shore. It would have been a moment both of fear and profound relief. Sixty-two of them, including five small children, had been crammed in the dark and noisome cargo-hold of this 19 foot boat for over a week, sharing the space with a cargo of shoes, leather, beans, soap, coffee and cooking oil, as their vessel crossed the notoriously rough stretch of sea between the southern tip of Korea and Japan. They have left no record of their journey, but I have spoken to others who made similar voyages. One man who made a much quicker crossing, concealed in the hull of a cargo vessel some seventeen years later, told me of the horrors of lying in the dark, confined space, without adequate food or water, as his boat ploughed through mountainous seas. “I wanted to die”, he said, “and I thought, ‘if I live, I will never, never do this again’”.4

|

Korean boat people arrested on arrival in Japan, 1946 |

But as the Hatsushima approached land, the quiet of the night was suddenly shattered. Alerted by the watchers on the hill, a police boat appeared from the harbour and sped towards the Hatsushima with engines roaring. Meanwhile a squadron of police accompanied by forty members of the local fire-brigade emerged from the darkness to line the water-front, the beams of their torches puncturing the darkness as they prepared to catch any of the boat’s crew or passengers who attempted to make it to shore.

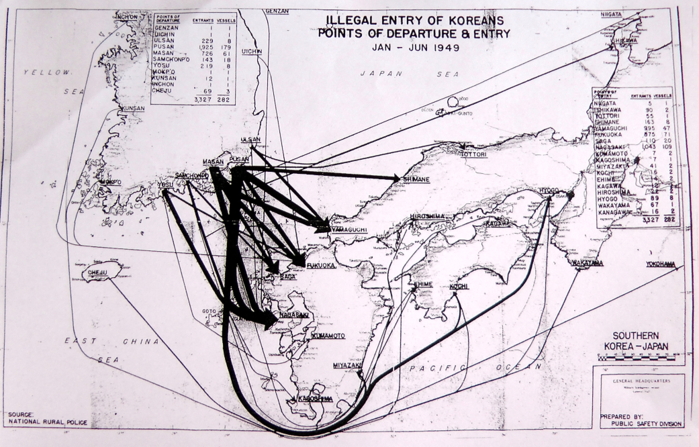

The Hatsushima was just one of many boats which made similar journeys between Korea and Japan in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Five other boats with a total of over 250 passengers were detained around the Cape Sada Peninsula in the first half of October 1948 alone. The following year the Allied occupation authorities in Japan produced a map depicting the “Illegal Entry of Koreans” for the period from January to June 1949.

This offers a graphic visual interpretation of statistics collected by the Japanese police. On the left-hand side is the carefully outlined contour of the southern end of the Korean peninsula, from which a tangle of aggressive black arrows flows eastward from Busan, Masan and Jeju Island in Korea into Kyushu, Shikoku and the western prefectures of Honshu in Japan. Each arrow traces an individual’s journey, and the thicker the arrow, the greater the number of known journeys – 3,327 in all.

By 1951, the last year of the Allied occupation, a total of 48,076 “illegal entrants” – 45,960 from Korea, 1,704 from the “Nansei Islands” (Amami and Okinawa), 410 from China and 2 from elsewhere – had been arrested, and it is likely that tens of thousands of others succeeded in slipping across the border without official permission in the late 1940s.5 The anxiety evoked by their arrival formed the environment for the creation of a border control system which, in broad outline, remains in place in Japan to the present day.

The concerns reflected in SCAP’s dramatic map of “Illegal Entry of Koreans” evoke contemporary echoes. Today, in many parts of the world, the unauthorized arrival of people in small boats arouses a mixture of powerful emotions, from sympathy to racist hatred. Today too (as in SCAP’s 1949 map) such arrivals are often depicted as something akin to an invading army descending upon the defenseless nation state. They are described as dangerous aliens. In fact, the language we use today seems uncannily similar to that of the Japanese government which, in 1949, expressed fears that many of the boat people arriving on its shores were “engaged in terroristic political activities.”6 Recent Japanese media reports have warned that a 21st century crisis on the Korean Peninsula could trigger the arrival of 100,000 to 150,000 boatpeople on Japan’s shores.7 Such images in turn fuel efforts to tighten entry controls and increase border surveillance. To understand how Japan’s existing border control system came into being, however, we need to return to the late 1940s and early 1950s – to the moment of official and media panic evoked by the arrival of boats like the Hatsushima.

The Hatsushima was just a small part of a much bigger picture. One minor historical accident, however, makes its journey distinctive. The local police on Cape Sada Peninsula and in the surrounding areas of Shikoku were so concerned at the repeated arrival of boat-people on their shores, and at other smuggling activities in the area, that they commissioned a special report on the problem. They also set in place a whole battery of special “anti-smuggling” measures to deal with the problem. Since Japan was still occupied by the Allied forces (and would remain so until April 1952) these measures required the co-operation of Allied troops stationed in Shikoku, who happened to be British and Australians; for Shikoku was one of the areas of Japan which had been assigned to the control of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), a force made up of soldiers from the UK, Australia, New Zealand and (until 1947) India.

The local headquarters of BCOF’s Division in the city of Takamatsu heard of the existence of the Japanese police report on smuggling problems around Cape Sada, and asked for it to be translated into English and sent to them in duplicate. After the end of the Allied Occupation of Japan, this report was filed away in the basement archives of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, where it lay undisturbed amidst the triumphal celebrations of Australia’s military past until I came across it during my search for material on the origins of Japan’s migration control system.

Similar reports were undoubtedly produced in many places, but (since the Japanese police are generally reluctant to open their archives to public scrutiny) it is not easy for historians to find them. So the 49-page typescript English translation entitled “Control of Illegal Entry into Ehime Prefecture” remains one of the most detailed publicly available accounts of the arrival of postwar immigrants on Japan’s shores, and of the way in which the Japanese and Allied authorities responded to their arrival. The report gives an account of the arrival of six boats, including the Hatsushima, on the western coast of Shikoku between 5 and 13 October 1948. It tells us where the boats came from, who was in them, and something about the motives of those who made this uncomfortable and dangerous journey to Japan. It also details the remarkably energetic mobilization of Japanese and Allied security forces and local people, who were determined to prevent the boat-people from setting foot on Japanese soil, or to apprehend them if they did manage to come ashore. From these six boats, I have chosen to focus on the case of the Hatsushima because it is particularly well documented. The report gives us the name of the boat, and it is possible to identify the place of origin of most of her passengers.8

Thanks to this historical accident, the voyage of the Hatsushima provides a starting point from which, many decades after the event, we can begin to reconstruct the story of migration and border controls in postwar Japan. Every journey, of course, was unique: the boats began from many starting points; the people they carried varied from penniless refugees to businesspeople and senior military officers. However, the example of the Hatsushima illustrates many of the key features which were repeated in other voyages of that time. Here I reconstruct its journey, its reception in Japan and the context of its arrival through material from the BCOF translation, combined with information from other occupation period documents, local histories and newspaper reports of the time.

The ship and its passengers are a microcosm through which to explore the many and troubled paths of migration which linked twentieth century Japan to the Asian mainland. To follow these paths, we need to find their starting points, and consider the complex web of forces that encouraged migrants to leave their homes and embark on uncertain journeys to Japan. We also need to consider the changing political landscape which determined whether the travelers were welcomed or arrested at their destination, and whether they came to be defined as “transient labourers” [dekasegi rôdôsha], “stowaways” [mikkôsha], “migrant workers” [ijû rôdôsha], “refugees” [nanmin] or even potential terrorists. At the arrival point, then, it is necessary to understand the background and perspective of the watchers on the shoreline, and of the police who hunted the boatpeople through the waters surrounding the Cape Sada Peninsula.

In my recently-published book, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era9, I have used stories like those surrounding the apprehension of the Hatsushima, to gain a perspective on Japan’s border controls that is missing from the bland reports on migration control produced in the ministerial offices of central Tokyo. Here I shall expand on this particular story as a way of exploring interconnected forces on both sides of the border that helped shape Japan’s postwar migration control system.

The Passengers

The Hatsushima had set off on its voyage to Japan at six o’clock in the morning of 26 September 1948, from Hallim on the west coast of the Korean island of Jeju. Its journey to Japan took eight days – an unusually long time; other boats which departed from the same area generally managed to reach Shikoku in five or six days.

Most of the people on board came from the town of Hallim itself, or from the surrounding villages, though a couple came from as far away as Jeju City in the north of the island. Today a rather sprawling industrial conurbation, Hallim in the 1940s was a quiet fishing port. The villages around it – Ongpo, Hyeopjae, Weollyeong – were little fishing and farming hamlets: huddles of thatch-roved cottages built around earthen courtyards. Jeju is a volcanic island whose forested slopes rise to the central peak of Mount Halla. Harsh soil and a lack of sizeable rivers make the island unsuitable for rice growing. In the villages which were home to the Hatsushima’s passengers, families earned a hard-won livelihood from the earth and the water: growing crops of millet and vegetables in small stone-walled fields, gathering seaweed and harvesting fish and shellfish from the sea.

The majority of the passengers, when questioned by the Japanese police who arrested them, gave their occupation as “agriculture”, though they also included a day-labourer, a tailor, a clerk and a Buddhist missionary. For many of the boat’s passengers, this was their second (or perhaps even their third, fourth or fifth) voyage to Japan. Their journey, in other words, was a continuation of the prewar history of sea-crossings linking Jeju and other southern parts of the Korean Peninsula to Japan. The police report which details the arrival of the Hatsushima notes that “as women divers were always coming over from the Cheju [Jeju] Islands to collect seaweed before the war, Cheju Islanders knew the geography of this Prefecture (especially the seas neighbouring South Ehime) very well.”10 The five other boats apprehended on the Cape Sada Peninsula in the same month also came from the western side of Jeju, and all but four of their 290 crew and passengers gave their registered addresses as towns or villages on Jeju Island.

Amongst the passengers who had made the journey to Japan in prewar days, some perhaps looked back with a certain nostalgia on that earlier, safer and more comfortable voyage. 35-year-old Ms. Yang, from a farming village near Hallim, (for example) had once lived in Tokyo. 17-year-old Ms. Koh had previously lived in Osaka, and her elder sister was still in that city, while their father was currently living in Tokyo. Mr. Soh, a young farmer from the northern part of Jeju Island was hoping to “meet an acquaintance whom he knew during his 3 years’ stay in Yokohama” and labourer Mr. Koh from Jeju City was planning to find a job in the company “for which he had once worked in Tokyo”.

Of the rest, almost all had family connections in Japan. The reasons they gave for attempting to enter Japan included: “to visit sister in Osaka”; “to visit husband in Kobe”; “to take back younger sister from Osaka”; “husband lives in Yokohama”; and, in the case of the Buddhist missionary (who had previously lived in Tokyo) “to visit grave”.11 The five children on board, who ranged in age from two to ten, were all described as being “accompanied by guardian”, and seem to have been taken by family friends to be reunited with parents from whom they had become separated. The ship’s captain himself was a man who originated from Jeju Island but lived on the Cape Sada Peninsula, where he dealt in second-hand goods and evidently also traded on the black-market. It seems very likely that he may have been related to some of the passengers whom he was bringing to Japan. The police concluded that, of the people arrested from the Hatsushima and the five other people-smuggling boats detected on the shores of Cape Sada that October, 78% had previously lived in Japan, and 24% had lived in Japan for more than fifteen years.12

The first time I encountered documents like the report on the Hatsushima, I was puzzled by a fact that also troubled the occupation authorities at the time. The boat appeared to be going in the wrong direction. When the Hatsushima set off from Jeju Island in the direction of Cape Sada, the Japanese economy lay in ruins – a shattered landscape vividly evoked by historian John Dower:

In 1948, women still scavenged for firewood and waited hours to buy sweet potatoes. Housewives still spoke bitterly of the indignity and exhaustion of standing in long lines with ‘dusty, dry, messy hair,’ as one wrote that February, ‘and torn mompe [baggy trousers], and dirty, half-rotten blouses, like animal-people made of mud.’ The homeless still starved to death. As late as February 1949, the press was still reporting that ‘only’ nine homeless people had died in [Tokyo’s] Ueno railway station that winter, in contrast to the hundred or more deaths in each of the previous thee winters.13

In Korea, on the other hand, thirty-five years of bitterly resented colonization had come to an end, and an independent South Korea had just held its first general elections. Why then were thousands of people risking their lives in overcrowded small boats in an effort to enter (or re-enter) the former colonial power?

The brief comments jotted down by the police who apprehended the Hatsushima give the first glimpse of answers to this question. 19-year-old Mr. Yang told police that he was planning “to work after visiting aunt in Osaka due to hard living condition in Korea”,14 while Mr. Cho, a young man in his mid-twenties, wanted “to visit Osaka as unable to live in native place due to difference in thought”.15 Behind these cryptic remarks, as we shall see, lies an entire history: the history of one of Asia’s most comprehensively forgotten mass migrations.

Locating the “Displaced”

Over the course of 1945 and 1946, more than a million Koreans had streamed homeward from Japan. This mass exodus had begun even before Japan’s capitulation to the allies. From late 1944 onwards, Japanese cities experienced devastating fire bombing raids, and those who could, fled to the relative shelter of the countryside. Workers who were unable to leave their jobs tried, where possible, to send their children to safety. For Japanese city-dwellers, “safety” generally meant the home villages where grandparents or other family members still lived. For Koreans in Japan, it meant home villages in Jeju, South Gyeongsang and elsewhere. Most families believed that the separations caused by this wartime evacuation would last a few months at most. None could have imagined the postwar drawing of lines, which for some, would make reunion perilous or even impossible.

Japan’s surrender on 15 August 1945 was long awaited by the Allies, but caught most ordinary Japanese people, and most of the people of Japan’s colonies, completely by surprise. As soon as Emperor Hirohito’s quavering voice had been broadcast across the Empire at midday on 15 August 1945, announcing Japan’s decision to “endure the unendurable” and accept defeat in war, a fresh wave of Koreans, Taiwanese and Chinese streamed towards the nation’s ports, seeking any boat willing to take them home. Needless to say, the most eager to leave were those who had been forcibly recruited for wartime labour, though in the first two months of the occupation some mine owners, desperately reliant on Korean labour, attempted to force them to stay, provoking strikes and riots at coal mines in Hokkaido and elsewhere.16 From September 1945, both SCAP and the Japanese authorities began to provide transport for returnees, and after the establishment of the US military government in Korea, ships used to repatriate Japanese residents in Korea were used on the return journey to transport Korean residents leaving Japan.

Conditions in the ports were crowded and confused, with desperate shortages of shelter and food: for, as they rushed to depart, Korean returnees crossed paths with throngs of Japanese soldiers and civilians returning from the lost colonial empire, and (as Lori Watt notes) contemporary reports suggest that Japanese officials treated departing Koreans much less favorably than returning Japanese.17 The official repatriation program was a massive logistical exercise carried out in very difficult circumstances. Its most remarkable achievement was to handle the return of more than five million Japanese to their homeland in a little over a year.18 Between the start of the Occupation and the end of February 1946, around 1.3 million Koreans had also left Japan either on their own initiative or on official repatriation ships.

To Japan’s Allied occupiers, the exodus was part of a process that would restore order to East Asia. The “displaced” were being put back in their proper places, the peoples were being “unmixed”,19 and SCAP both hoped and expected that almost all Koreans in Japan would return home. But as a secret report compiled from US intelligence sources noted, “these hopes failed to materialize”.20 In March 1946, the occupation authorities attempted to survey the number of Koreans, Taiwanese and Okinawans still living in Japan and the number seeking repatriation. A total of 647,006 Koreans were counted, of whom 514,060 stated that they wished to go home (9,701 requesting to be sent to the North of the Peninsula, and the rest to the South).21 On this basis, SCAP planned a massive evacuation exercise, which would have seen 1,500 people per day shipped out of the port of Senzaki, and 4,500 out of the port of Hakata.22 But by the middle of the year, it became clear that the numbers actually boarding the repatriation ships to Korea were much lower than expected. Ultimately, less than 100,000 Koreans were repatriated between April 1946 and June 1950 (when the outbreak of the Korean War put an end to the repatriation program). All went to South Korea apart from two small groups – totaling 351 people in all – who were repatriated to the North in March and June of 1947.23 Around 600,000 Koreans remained in Japan.

Meanwhile, to the even greater consternation of the occupation authorities, little boats like the Hatsushima were embarking on the journey in the opposite direction. The alarm was first raised some two-and-a-half years before the Hatsushima set off on its voyage from Hallim. In April 1946, Allied forces stationed on the west coast of Japan began to report “illegal entry into Japan by Koreans who have previously been repatriated. Most cases, however, are detected and the offenders re-shipped to Korea.”24 By the middle of the year, the initial confidence that “most are detected” was waning, and being replaced by the fear of a wave of migration rapidly slipping beyond the control of the authorities. In August, Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger, commander of the US 8th Army, reported that

Korean immigrants are illegally entering Japan by ship in large numbers. The rising incidence of cholera among those apprehended and the possibilities of its spreading, are a major threat to the health of the occupation forces and the Japanese population.25

Against this background, the occupation forces commissioned a Korean resident in Japan, Cho Rinsik, to examine the reasons for the influx of entrants from Korea. Cho’s survey of detained “illegal entrants” found that “these stowaways are all former residents of Japan”, and that 80% had come to Japan “on account of hard living” and to obtain “daily food”.26 Cho was critical of the tight restrictions which had been imposed by the occupation forces on Koreans being repatriated to their homeland from Japan. They were officially allowed only the luggage that they could carry with them and a sum of 1000 yen, and, as Cho discovered, “this means that they could not live a month with the money they had brought with them”.27 Not surprisingly, many promptly turned round and attempted to head back to Japan, where in some cases they had left behind houses, post office or bank accounts, and even small businesses.28

After protests from Koreans in Japan as well as from the head of the displaced persons’ section of the US Military Government in Korea, SCAP made small changes to its repatriation regulations, allowing departing Koreans to take a somewhat larger amount of luggage as well as bank and postal savings books and insurance policies.29 But since there was no legal way to send money between the two countries, this last concession meant little. The consequences of the policy were still being felt in 1948. As the police who intercepted the Hatsushima observed, people returning from Japan to Jeju had found that “they gradually use up their money and there are no arrangements for the assistance of repatriates such as there are in Japan so they are reduced to poverty and again yearn for Japan”.30

The impact of the policy went far beyond its effect on the lives of individual families. In the year following Japan’s surrender some 60,000 people returned from Japan to Jeju Island, many with nothing but the regulation 1000 yen and the goods they could carry on their backs. While the allied occupation authorities and the Japanese government were eagerly encouraging Koreans to return home, the US Military Government in Korea was doing little to prepare for their arrival.31 The influx of repatriated Koreans from Japan immediately followed the return of people who had been evacuated to the island in the final stages of the war to escape the bombing raids on Osaka and other cities. Within a couple of years, Jeju’s population had grown by around 25%. The emigrants who for years had regularly sent money home to their families in Jeju, helping to sustain the island’s economy, returned to become an impoverished burden on their communities.32

A crop failure in 1946 added to the misery, creating the environment for the epidemic of cholera which claimed the lives of 369 islanders and provoked panic amongst the occupation authorities at the possible spread of disease carried by unauthorized border-crossers.33 Because of its deep incorporation into the migration networks of the Japanese Empire, then, Jeju suffered particularly severely from a problem which beset the entire Korean Peninsula as some 4 million overseas Koreans (including around 1.4 million from Japan) headed home.34 And this background of unemployment, poverty and epidemic in turn was to foment an even greater upheaval: a disaster which led to the flow of a new wave of migrants, including the passengers on the Hatsushima, from Jeju and other parts of Korea to Japan.

From Liberation to Conflagration

The boat-people who arrived on the Cape Sada Peninsula in October 1948 spoke of the age-old causes of migration – poverty and hunger. But they also spoke of the darker forces propelling their flight across the sea. The fragments of their words preserved in written records depict a society riven by violence and gripped by fear:

“On Cheju Island,” one is reported as saying, “the communists have retired into pill-boxes in the mountains and come out at night to commit misdeeds,” adding enigmatically, “it is said that there is a fair number of Japanese with them.”

“There is a curfew imposed when a siren sounds after sunset,” says another, “if anyone goes out after the curfew he is thoroughly investigated by the police on suspicion of being connected with the communist party.”35

In the light of the events taking place on Jeju Island in September and October 1948, the words “thoroughly investigated” have a disturbing ring.

Jeju Island had always been a place apart, proud of its distinctive history and traditions. Once the independent Kingdom of Tamna, whose ships had traded widely along the eastern seaboard of Asia, from the 15th century onward Jeju had gradually been absorbed into the Korean Kingdom. The envoys of the central government, who ruled the island from their elegant walled compound in what is now Jeju City, attempted to impose their own vision of order on the island. But the authority of the center did not run very deep. The island’s villages preserved their own dialects and ways of life, their own shamanic rituals and the spiritual beliefs embodied in “stone grandfathers” (tol harubang): the basalt rocks carved in human form which even today stand guard over Jeju’s landscape.

This tradition of difference, together with the acute social and economic dislocation of the immediate postwar years, helps to explain why problems which beset all of US-occupied Korea erupted in Jeju in a particularly dramatic manner. Jeju, across the sea beyond the furthest end of the Korean Peninsula, was one of the last areas in the south to experience the arrival of US occupation forces in Korea. Like other Koreans, most islanders had welcomed liberation from colonial rule, believing that it would mean immediate independence. Local committees – known as “Nation-Building Preparatory Committees” [Geonguk Junbi Uiueonhui] – quickly began to spring up all over the country, taking over control from the departing Japanese colonizers and preparing for full independence. By 6 September, the central committee in Seoul, led by social democrat Yeo Unhyeong, had declared the founding of an independent Korean People’s Republic [Joseon Inmin Gonghwaguk]. On Jeju the local committees, which (after the proclaiming of the People’s Republic) had been renamed “People’s Committees”, replaced officials who had collaborated with the colonizers, organized patrols to fill the void left by the disbanded police and opened night schools to tackle problems of illiteracy.36 Built on the long tradition of communal village life, the People’s Committees were quickly able to establish their authority and were, in the early stages, driven more by nationalism and local pride than by any complex ideological agenda.37

But on 8 September 1945, two days after the declaration of the Korean People’s Republic, the US army of occupation landed at the port of Incheon, from where it marched to Seoul to establish the Military Government. With the Soviet Union rapidly imposing its influence in the north of the Peninsula, the US saw the both the national People’s Republic and the local People’s Committees as dangerously tainted by communism. They refused to recognize either, and instead began establishing their own preferred model of government in South Korea. This centred on the figure of Syngman Rhee, an elderly nationalist leader who had spent most of the past thirty years in the United States. At the local level, American occupation strategy in Korea involved retaining the services of many officials and policemen who had built their careers within the Japanese colonial system.

Effective US military control was not established on Jeju until the very end of 1945, and when it did arrive, efforts to dismantle the People’s Committees and reinstate those seen as “colonial collaborators” was bitterly opposed by much of the population. The result, perhaps predictably, was the very opposite of the US Military Government’s intentions: it increased support for the main pro-Marxist political grouping, the South Korean Labor Party. The influence of socialism and communism was also strengthened by the legacy of colonial migration. Some Jeju migrants had been active in labor unions in Osaka and other Japanese cities, or had come into contact with Marxist ideas through education in Japan (where Marxism remained an influence in universities well into the 1930s). Among them were figures like Yi Dok-Gu, who had studied at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto before returning to Jeju as a teacher, and who was to emerge as one of the main leaders of the uprising which occurred in 1948.

The direct antecedents of this uprising go back to 1 March 1947, when a large body of islanders gathered in Jeju City to celebrate the anniversary of the 1919 anti-colonial mass demonstrations, generally seen as the birth of Korea’s independence movement. By 1947, the United States was coming to see South Korea as a vital buffer protecting a gradually reconstructing Japan from the menace of communism. It was eager to establish an elected South Korean regime which would provide a strong bulwark against communism and (it was hoped) gradually take over the tasks of maintaining security from the US occupation forces. As Koreans became aware that the division of their country was going to be more than a passing temporary phase, the prospect of the creation of a separate government in the South, rather than a single, united independent Korea, aroused fierce opposition. In Jeju, anger towards the policies of the occupiers was intensified by a crop requisition scheme, introduced to deal with the chronic food shortages but (to local farmers) horribly reminiscent of hated wartime Japanese policies.

On March 1 1947, it is estimated that as many as 30,000 people – about one-tenth of the island’s population – marched through Jeju City to the square in front of the old government building where the police headquarters was located, and where a large contingent of police was waiting to confront the marchers. According to some accounts, trouble began when a child in the crowd was knocked down by a police-horse.38 Some of those who witnessed the incident began to throw stones at the police, who panicked and fired into the crowd, killing six people.39 One of those killed was a fifteen-year-old schoolboy, another a woman carrying a small baby in her arms (the baby survived).

|

4.3 Memorial in Jeju erected more than six decades later |

The response to these killings was a massive island-wide strike, in which bank clerks and government officials, as well as factory workers, farmers, students, teachers and others took part.40 The strikers demanded an enquiry into the shootings, and the dismissal of those responsible. The US Military Government conducted an investigation, and expressed “regret” at the incident, but also portrayed it as the result of communist agitation by the South Korean Labor Party. Further police reinforcements were brought into the island, along with a detachment of the much-feared North-West Youth League – an anti-Communist vigilante organization formed from those who had fled south from the Soviet occupied northern half of Korea.

4.3 Korean War and the Invisible Refugees

In a pattern which was repeated across the country during the lead up to South Korea’s first elections, large numbers of suspected “subversives” were arrested, and some were tortured and killed: among them a young man from the village of Keumneung near Hallim, home to at least one of the Hatsushima’s passengers.41 In response to this escalating violence, some prominent local members of the Korean Labor Party decided to strike back. A group of several hundred activists withdrew into the forests of Mt. Halla, where they set up base camps from which, on 3 April 1948, they issued a call to arms to their fellow islanders, and launched an attack on police stations and the homes of prominent right-wing officials, killing twelve people. The date was to become enshrined in Korean history: the uprising on Jeju, and the massacres which followed, are known today as the “4.3 Incident” [Sa-Sam Sageon].

|

Wall surrounding a Jeju concentration camp for those arrested during the uprising |

By the time South Korea’s first election was held on 10 May 1948, then, Jeju Island was already in a state of civil war, and sporadic violence was widespread throughout the country. The election was held in an atmosphere chillingly depicted in the reports of the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK), which was brought in to oversee the process. Despite threats from the left to disrupt the elections and even to kidnap or kill officials, the day was described as being generally quiet, but the quiet was an ominous one. In Busan, the major port on the southern tip of the peninsula, for example, polling booths were guarded by members of the local youth group “armed with heavy sticks and long pointed bamboo pikes.” In the nearby city of Ulsan, the observers were informed on the eve of the poll that the chairman of the local election committee “had been shot that day and his head cut off by a Japanese sword.” Elsewhere, a Canadian observer discovered that one of the candidates had been tortured to death by the police, while other observers reported that “police reinforcements were sent to drive out a raiding force of about one hundred. A number of police, civilians and raiders were killed in this raid, but voting continued.”42 Further information was left out of the official reports of the mission, but passed on by word of mouth. The Australian delegate on UNTCOK, S. N. Jackson, recounted to a fellow senior diplomat “a rather hair raising story of how an American military observer was kept awake in a small village on the night of election day by the screams of tortured prisoners who had been picked up by police.” The diplomat went on to report that “Mr. Jackson dismissed this as part of the normal Korean life, but said he believed some enquiry was being made.”43

Delegates from the UN Commission also visited Jeju in the month before the election but found the island in a state of siege, so that “it was not possible for the group to carry out any independent enquiries.”44 In fact, election day on Jeju was marked by boycotts, arrests, kidnappings and attacks on polling stations in which 29 people were killed. As a result, voting on the island was first postponed, and then abandoned altogether. Astonishingly (in the light of these events) on 25 June 1948 the UN Temporary Commission on Korea, which was under intense pressure from the US government to endorse the elections, proceeded to pass a resolution certifying the South Korea election as “a valid expression of the free will of the electorate.”45

Following the official establishment of the Republic of Korea, under the presidency of Syngman Rhee, on 15 August 1948, reinforcements of police and security forces were sent to Jeju, and draconian restrictions on the movement of islanders were imposed as the government prepared for a major offensive. It was at this point that the six boats apprehended by police on the Cape Sada Peninsula slipped out of Jeju ports under cover of darkness carrying people who hoped to find refuge in Japan.46

The historical evidence suggests that the “4.3 Incident” had begun as a largely spontaneous uprising emerging from a spiral of violence between local activists and heavy-handed security forces. As the uprising turned into a prolonged guerilla campaign, however, leading insurgents developed closer links with fellow-communists in the northern half of Korea, and in August 1948 key leaders of the Jeju movement traveled to Haeju, north of the 38th parallel, where they took part in a secret congress of the South Korean Labor Party. However, the American military (who retained overall command of the South Korean security forces throughout) interpreted the events in Jeju as being, from start to finish, an international communist conspiracy orchestrated from Moscow and Pyongyang. Significantly, they believed that “there is also connection with the Japanese Communist Party through the intermediary of agents who ply between Masan and Pusan and unknown Japanese ports.”47 This belief helps to explain the extreme alarm with which occupation authorities both in Korea and Japan viewed the movement of small boats across the sea between the two countries.

The voices of the Hatsushima passengers as they explain the motives for their flight across the sea – words transcribed by police, translated into English, and typed up for the occupation forces’ records – echo strangely over the decades. Those whose statements have names attached to them speak of Communist violence, and of themselves as its victims. “If the influential people of the villages co-operate with the police in the present attacks on the Communist Party,” says one, “they are persecuted by the Communists. Also, the Communists are active in seizing smuggling ships coming from Japan and carrying out a careful search for arms.” Rather surprisingly, the speaker goes on to identify himself as a member of the right-wing Northwestern Youth League, an organization which, at that moment, was organizing itself for a major assault on those it identified as its opponents. “We have fairly good weapons,” he says, “and while the actual strength of the organization is not known it is said that there are about 200,000 members throughout South Korea.”

All this raises delicate questions about the statements which refugees leave in the hands of the authorities who detain them. The Hatsushima passengers were desperate to be allowed into Japan, and were undoubtedly aware that their chances of winning a sympathetic hearing from the Japanese police were greater if they were seen as victims of the “Red menace” than if they were suspected of communist sympathies. Their chances might also be helped if they could present themselves as bearers of valuable information; for the Japanese police and occupation authorities saw the unauthorized arrivals not only as a threat to security, but also as a valuable source of intelligence about events in Korea. The coming together of these motives, compounded by translation and transcription, surely helps to explain the slightly surreal air that surrounds some of these statements.

And yet, their words convey a message of fear which seems both unmistakable and genuine. “The people are caught between two fires,” says one anonymous boat-person, “if they take the side of the police against the Communists or that of the Communists against the police, they are oppressed by the other side.” The precise number of people killed in the aftermath of the 3 April rising is still unknown, but is estimated at between 20,000 and 30,000: some police and other officials killed by the insurgents; a greater number insurgents killed by the police and vigilante groups, but the greatest number of all were those caught in the middle of this scorched-earth policy, which by the middle of 1949 had utterly transformed the human geography of the island.

The flow of boat people from Korea to Japan was, of course, further greatly expanded from the middle of 1950 when the Korean War broke out, and refugees from all over the country fled the fighting, overwhelming the capacity of refugee camps set up to receive them in the far south of the Peninsula. The Allied occupiers evacuated their own nationals from Korea to Japan when the Korean War broke out, but refused to allow the entry of Korean refugees into Japan. Meanwhile, the first acts of the Japanese government in response to the outbreak of the Korean War on 25 June 1950 were to tighten controls against “illegal entry” from Korea and to institute “a close watch over approximately 800,000 Koreans resident in Japan, to prevent any uprisings.”48 Political events on the Korean Peninsula, in other words, added fuel to the fire of longstanding colonial prejudices against the Korean community in Japan, heightening perceptions (on the part of both of the Japanese government and the occupation authorities) of the community as a hotbed of subversion. These fears reached a peak in the final months of 1951, following protests demonstrations by Koreans living in Kobe. Although the immediate cause of the demonstrations were issues of taxation and access to welfare, the Japanese police were quick to link the events to rumours of a North Korean plot to “organize the Korean underground” in support of the Communist side in the Korean War.49 In response, Chief Cabinet Secretary Okazaki Katsuo announced that “increasing disturbances and subversive activities by Korean Communists in this country made it necessary for the Japanese government to deport them.” The deportation plan drawn up by the government in December 1951 reportedly envisaged a mass deportation of 60,000 Korean residents “who are alleged Communists or engaged in subversive activities in Japan.”50

Without Papers

The police report on the arrival of the Hatsushima in 1948 contains one particularly puzzling sentence: “Among the illegal immigrants,” it says, “there were many who had previously been registered in Japan and were returning to Japan.” If these were people who were legally registered in Japan and were returning to homes there into escape a de facto civil war in their birthplace, what was it that made them “illegal immigrants”? To understand the fate of these sixty-two people and many others like them, then, we need to consider the complex and confused state of nationality in occupied Japan. As colonial subjects, Koreans and Taiwanese had possessed Japanese nationality under international law until 1945, and until the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty former colonial subjects who remained in Japan retained that nationality, in legal theory at least. In the words of SCAP’s legal section, after the annexation of Korea in 1910 “the Japanese government has long regarded Koreans as having the status of Japanese nationals and during the Occupation to date has enacted no Diet legislation modifying or changing that status”.51 Koreans who had continued to live in Japan since colonial times “will continue to retain the status quo of Japanese nationals until such time as a definitive settlement can be made by Japanese Diet legislation and a mutual understanding legally concluded through official negotiation between the Japanese government in a sovereign capacity and the Republic of Korea.”52

In practice, however, matters were much less clear-cut than these statements suggest. In December 1945, for example, the occupation authorities had acquiesced in the introduction of a new Japanese voting law which, as part of Allied policies to democratize Japan, extended the franchise to women, but also removed the franchise from Koreans and Taiwanese in Japan (who had been eligible to vote under the old imperial system).53 The change apparently came about because of pressure from Japanese politicians, who feared the radical tendencies of newly liberated former colonial subjects. Four months later, in March 1946, SCAP informed the Japanese government that “non-Japanese” who were repatriated to their homelands would not be allowed back in Japan without the express permission of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.54 Most of the “non-Japanese” in question were Koreans.

On 11 June 1946, the Japanese government, with the blessing of the Allied occupation authorities, issued “Imperial Ordinance 311”, a decree which imposed a punishment of up to ten years imprisonment on anyone found guilty of “acts prejudicial to the objectives of the Occupation Forces.” (The police who apprehended the Hatsushima carefully appended a copy of this Ordinance to their report, since it provided the legal basis for their actions in detaining its passengers.)55 The ostensible reason for this draconian measure was an upsurge of trade union activity following a May Day demonstration in Tokyo. But it was very quickly applied to the very different problem of controlling cross-border movement. Just over a month after the Ordinance was issued, the headquarters of the US 8th army had advised British Commonwealth troops engaged in border-patrol duties in Japan that “illegal entry of repatriated Koreans is considered an act prejudicial to the Occupation Forces and Provost Courts may take jurisdiction.” The punishment included deportation.56 These restrictions on cross-border movement were in fact applied retrospectively, so that any Korean resident in Japan who had returned to Korea and re-entered Japan after the start of the occupation on 2 September 1945 was now deemed to be an “illegal entrant”.

Alien Registration and the Migration Control Law

|

1946 Tokyo demonstration by Koreans against Occupation policies |

It was against this background of ambiguous nationality and fears of subversion that the two major cornerstones of Japan’s migration control system – Alien Registration and the Migration Control Law – were put into place. After some debate between SCAP and the Japanese authorities, on 2 May 1947, the Japanese government issued an Ordinance for Registration of Aliens, which required all foreigners in Japan (with certain exceptions) to carry registration cards. The exceptions were members of the Occupation force, their spouses and employees, and anyone in Japan on the official business of a foreign government – in other words, the great majority of Allied nationals in Japan during the Occupation years. Other foreigners in Japan were required to carry Alien Registration certificates at all times, and those who failed to produce them for inspection when asked to do so by the police could be sentenced to a 10,000 yen fine or one year’s penal servitude. People imprisoned for this offence could also be deported.57

Despite SCAP’s official view that Koreans who had remained in Japan since colonial times retained their Japanese nationality, the Alien Registration Ordinance specifically included in its scope ‘those designated by the Minister of Foreign Affairs among Formosans [Taiwanese], and Koreans’.58 There was, however, a distinction between the two groups: three months earlier, the Chinese Nationalist government had reached an agreement with Japan which ensured that all Taiwanese who registered as Chinese with their Tokyo Mission would be treated as United Nations nationals. As a result, though Taiwanese were required to carry Alien Registration documents, they benefited from the advantages of being allies of the occupier in an occupied country: better rations and immunity from Japanese taxes and criminal jurisdiction.59 Koreans, however, continued to be treated as ‘Japanese’ in most respects (except the right to vote), while also facing widespread discrimination and constituting by far the largest group forced on pain of arrest to carry Alien Registration certificates. Understandably, this policy generated considerable resentment amongst the Korean community in Japan, aggravating the tensions between them and Occupation forces.

These policies, in other words, fuelled a cycle of political antagonism. The vast majority of Koreans in Japan (well over 90%) came from the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, but some had anti-colonial and left-wing political views, and many were disturbed by the establishment of separate regimes in South and North Korea. During the early stages of the Occupation, the main Korean community organization, League of Koreans Residing in Japan [generally known in Korean by the abbreviation Choryeon, Japanese as Chôren, and in English as “the Korean League”], had cooperated with the allied occupiers in helping to keep law and order.60 As time went on, however, the organization became increasingly critical of the occupation authorities, and the allied occupiers in turn increasingly saw it as a hotbed of subversion. In 1949, following major demonstrations sparked by Japanese government efforts to close down the Korean community schools which had been set up for minority children after the end of the war, MacArthur’s occupation headquarters declared the Korean League a prohibited organization and ordered its assets to be confiscated. In the years that immediately followed the banning of the League, some left-wing Koreans in Japan responded by cultivating closer links with the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), and both the JCP and left-wing members of the Korean community took part in protests against the use of Japan as a staging post for US involvement in the Korean War.61

The politics of nationality indeed became a topic of particularly heated debate as internal conflict in Korea gave way to full-scale war. Some seven months after the outbreak of the Korean War, in January 1951, serious work on the creation of Japan’s first national migration control system began when Nicholas Collaer, a senior official who had recently retired from the US Immigation and Naturalization Service, arrived in Tokyo to advise on the drafting of a Migration Control Ordinance. Collaer had begun his career as an INS officer on the Mexico-US border, and from 1942 on, had been in charge of the wartime internment camps in which the US held ethnic Japanese from Peru and other Latin American countries deported to the US as suspected “subversives”.62 His robust attitudes to border security are evident from an article published in a popular US magazine in 1949. In terms that have an oddly contemporary ring, Collaer describes the US border as “10,000 miles of trouble” besieged by people-smugglers who include the “human coyote”: “a particularly cunning type of alien smuggler”. The article concludes: “Aliens who try to crash our borders may be subversive, criminal or even diseased. But, in any event, all are breaking U. S. immigration laws and must be stopped. I can assure you that your Border Patrol is meeting the challenge. Day and night you’ll find us keeping vigil over America’s 10,000 miles of trouble.”63

Similar views were reflected in Collaer’s proposals for Japan’s first national immigration control law, in which he emphasized the need to give the state extensive discretionary powers to exclude or deport foreigners, particularly those deemed likely to engage in sabotage or subversion. As a stop-gap measure before the introduction of this law, the Japanese government “with the energetic assistance and advice of Mr. Collaer” also drafted an ordinance which would officially have reclassified Taiwanese and Koreans as “aliens”, and created swift and simple procedures for deporting “subversive or undesirable aliens or criminals within specified classes.”64 This approach coincided with the views of SCAPs Military Intelligence Section which, in July 1951 proposed that the powers given to occupation force to detain Japanese civilians suspected of war crimes should now be deployed to arrest and deport “subversive” Koreans.65

But both of these proposals ran into firm opposition from SCAP’s Legal Section, which pointed out that arbitrary attempts to redefine Koreans in Japan as “aliens” could, amongst other things, “be interpreted by the world at large as discrimination against a racial minority.66 In the end, Collaer’s recommendations for extensive and discretionary deportation powers were incorporated into the Migration Control Ordinance which came into effect in November 1951;67 but the nationality status of Koreans and Taiwanese remained ambiguous and undefined until 28 April 1952 – the day when the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect and the occupation of Japan ended.

|

Legacy: Japanese Patrol boat guarding the Tsushima Straits against illegal Korean entry. The gree sign on the side of the boat say “dial the hotline if you see or hear of illegal entrants or smuggling!” Photograph by Li Narangoa. |

On that day, the Japanese government unilaterally rescinded the Japanese nationality of former colonial subjects living in Japan. However, since the nationality of Koreans and Taiwanese in Japan had still been ambiguous when the Migration Control Ordinance was drafted, the terms of the Ordinance offered no means by which they could regularize their residence status in Japan. Instead, a regulation was introduced stating that Koreans and Taiwanese who had entered Japan before the start of the Allied Occupation would be “allowed to remain in Japan, even though they still had no official residence status, until such time as their residence status and period of residence has been determined.”68 In other words, they possessed no legally-defined right to live in Japan, but were merely there on the sufferance of the authorities until the government decided what to do with them. Herein lay the source of problems which were to beset the Korean community in Japan for decades, and whose legacies have yet to be wholly overcome. And although the Allied occupation authorities baulked at the Japanese government’s 1951 proposals for a mass deportation of 60,000 “subversive” Koreans, the desire of some sections of Japanese officialdom to rid the country of people viewed as shiftless “subversive aliens” was later to exercise an important influence on the mass repatriation of Koreans from Japan to North Korea, which began in 1959.69

Unhappy Returns

In the meanwhile, what had become of the sixty-two passengers apprehended on the Hatsushima in 1949? Their fate is not entirely clear, but it seems that they were all transported to Hario Detention Centre, and thence deported to South Korea. I wonder what they found when they arrived there.

One of the passengers, 22-year-old Ms. Kang, from Donggwang village, had boarded the Hatsushima in the hope of returning to Osaka, where she had once lived. Six weeks after she arrived at Kawanoishi on the Cape Sada Peninsula, the authorities on Jeju introduced a scorched-earth policy under which all villages on the middle slopes of Mt. Halla were to be evacuated and burnt to the ground. Donggwang was one of the 130 villages chosen for destruction. About 150 of its villagers were killed, and many of the survivors spent the winter months living in caves in the mountains.70 I have visited the site where parts of Donggwang village once stood. It is very peaceful now. Tall grass grows over a few tumbled boulders on the hillside, and as you look at the landscape, you would never guess that a village had stood there at all.

Recommended citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Guarding the Borders of Japan: Occupation, Korean War and Frontier Controls, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 8 No 3, February 21, 2011.

Notes

1 “CSDIC Translations BOl Entry intoū, held in the Australian War Memorial, Canberra, file no. AWM 144, 417/1/27, p. 11.

2 Ehime Ken, Ehime Ken Shi Gaisetsu, vol. 2, Matsuyama, Ehime Ken, 1960, p. 2.

3 Ibid., p. 540-541.

4 Interview with O. Y., former undocumented migrant to Japan, Tokyo, 12 January 2007.

5 Hōmushō Nyûkoku Kanrikyoku ed., Shutsunyûkoku Kanri to sono Jittai – Shōwa 39-nen, Tokyo, Ōkurashō Insatsukyoku, 1964, p. 16.

6 Ibid.

7 See for example Asahi Shimbun, 5 January 2007.

8 Identifying place names in Occupation period documents is sometimes a difficult task. Korean place names have generally been transcribed by Japanese officials, who give the Japanese (rather than the Korean) pronunciation of the characters which make up the place name. These names have then been transcribed (sometimes inaccurately) into the Roman alphabet, adding a further layer of complexity to the process.

9 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

10 “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948” op.cit., p. 5.

11 Ibid., pp. 23-27.

12 Ibid., p. 14.

13 John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, New York, W. W. Norton, 1999, p. 101.

14 “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948”op.cit., p. 27.

15 Ibid, p. 26

16 Kim Tae-Gi, Sengo Nihon Seiji to Zainichi Chōsenjin Mondai: SCAP no Tai-Zainichi Chōsenjin Seisaku 1945-1952, Tokyo, Keisō Shobō, 1997, pp. 134-135.

17 Lori Watt, When Empire Comes Home: Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan, Cambridge Mass., Harvard East Asian Monographs, 2009, pp. 92-93.

18 Dower op.cit., p. 54.

19 Watt, When Empire Comes Home, p. 195.

20 “Korean Minority Problems in Japan (from US Intelligence Agencies)” in BCOF Quarterly Occupation Intelligence Review no. 2 (secret), August 1948, in file “Intelligence Reports, Quarterly Occupation Intelligence Review”, series no. 1838/283 control symbol 481/1/6, held in Australian National Archives, Canberra.

21 Ōnuma Yasuaki, Tan’itsu Minzoku Shakai no Shinwa o Koete: Zainichi Kankoku- Chōsenjin to Shutsunyûkoku Kanri Taisei, Tokyo, Tōshindō, 1986, p. 38; see also Hōmushō Nyûkoku Kanrikyoku ed., Shutsunyûkoku Kanri to sono Jittai – Shōwa 39-nen, Tokyo, Ōkurashō Insatsukyoku, 1964, p. 14.

22 Hōmu Kenshûjo, Zainichi Chōsenjin shogû no suii to genjō, Tokyo, Kohokusha, 1975, p. 59.

23 Hōmushō Nyûkoku Kanrikyoku op.cit., p. 14.

24 2 NZEF (Japan) Op. Report no. 2, 5 April to 12 April 46, in Archives of New Zealand, Wellington, file. ref. no. WA J 6815 6512, “Operation Reports – Mar. 46 – Mar. 47”.

25 Memo from R.L. Eichelberger, “Suppression of Illegal Entry of Korean Immigrants to Japan”, 10 August 1946, held in Australian War Memorial, Canberra, file no. AWM 114/1/27, “Illegal Entry of Koreans into Japan”.

26 “Report on Stowaways”, attached to the memo “Korean Stowaways in Japan” from Lt. Col. Rue S. Link, Kyushu Military Government Headquarters, Fukuoka, to Commanding General, I Corps, APO 301, 19 August 1946; in GHQ/SCAP Records RG 331, Box no. 385, Folder no. 014, “Civil Matters, Binder #1, 2 January 1946 thru 19 January 1948 (Japan, Korea, Miscellaneous), p. 1.

27 Ibid., p. 1

28 Ibid, p. 2

29 Richard Hanks Mitchell, The Korean Minority in Japan, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1963, p. 161.

30 “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948”op.cit., p. 17; on the problems of repatriation, see also Mark E. Caprio and Yu Jia “Legacies of Empire and Occupation: The Making of the Korean Diaspora in Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 37-3-09, September 14, 2009.

31 Kim Tae-Gi op.cit., pp. 262-263.

32 Heo Yeonson, Cheju Yonsan, Seoul, Minshuka Undō Kinen Jigyōkai, p. 28; see also Hyun Moo-Am, “Mikkō, Ōmura Shûyōjo, Chejudō: Ōsaka to Chejudō o Musubu ‘Mikkō’ no Nettowâku”, Gendai Shisō, vol.35, no. 7., June 2007, pp. 158-173, particularly p. 165.

33 Heo op.cit., p. 30.

34 See Moon Gyeong-Su, Chejudō Gendaishi, Tokyo, Shinkansha, 2005, p. 25.

35 “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948”op.cit., p. 15.

36 Moon op.cit., pp. 34-35.

37 Ibid., pp. 38-41.

38 Heo op.cit., p. 41.

39 See memo by D. W. Kermode, “Korean ‘Independence Day’ Disturbances – Statement by Director of Police Dpeartment to M. Kermode and Mr. Bevin (received 28th April”, 28 April 1947, in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no. A1838, control symbol 506/1, “Quelpart Island – Cheju Province”.

40 See memo by D. W. Kermode, “Korean ‘Independence Day’ Disturbances”, 24 April 1947, in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no. A1838, control symbol 506/1, “Quelpart Island – Cheju Province”; also Heo op.cit., pp. 45-57.

41 Heo op.cit., p. 59; see also “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948”op.cit., p. 23.

42 “Report of the Work of the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea”, by S. N. Jackson, Australian Delegate, August 1948, held in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no A1838, control symbol 852/20/4 Part 3, “Korean Commission”, 1948.

43 Confidential dispatch no. 107/1948 from Australian Mission in Japan, 19 May 1948, in in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no A1838, control symbol 852/20/4 Part 4, “Korean Commission”, 1948.

44 Confidential dispatch no. KJ17, from the Australian Representative, United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea, 19 April 1948, in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no A1838, control symbol 852/20/4 Part 4, “Korean Commission”, 1948.

45 United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea, “Elections of 10 May 1948 – Resolution Adopted at the Sixty-Ninth Meeting, 25 June 1948”, in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no A1838, control symbol 852/20/4 Part 4, “Korean Commission”, 1948.

46 “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948”op.cit., p. 11.

47 Departmental dispatch no. 230/1948 from Australian Mission in Japan to Department of External Affairs, Canberra, “US Intelligence Information on Korea”, in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no. A1838, control symbol 852/20/4 Part 5, “Korean Commission”, 1948.

48 See “Precautions against Illegal Entry of Koreans”, 26 June 1950, and “No Official Japanese Statement on Korea”, 26 June 1950, wire reports held in National Archives of Australia (NAA), Canberra, series no A 1838, control symbol 3123/7/27, “Korean War – Japan – Policy”, 1950-1953.

49 Departmental Dispatch no. 74/1950, “Disturbances in Japan Created by Koreans”, in NAA, series no. A1838, control symbol 3127/7/27 op.cit.

50 “Move to Deport Koreans from Japan”, 27 December 1951, wire report in NAA, series no. A1838, control symbol 3127/7/27 op.cit.

51 Legal Section Memorandum for Chief of Staff, “Deportation of Subversive Aliens”, 17 July 1951, in GHQ/SCAP Records, Box no. LS-1, folder no. 3, “Top Secret File no. 3”, Jan. 1950-Nov. 1951, held in National Diet Library, Tokyo, microfiche no. TS 00327-00329, p. 5. Interestingly, the Legal Section argued that in terms of international law the Alien Registration Ordinance (discussed below) which SCAP itself had proposed, and which was applied to Koreans, did not and could not alter the Japanese nationality of Koreans in Japan; Memorandum from Legal Section to Chief of Staff, “Deportation of Subversive Aliens”, op.cit. p. 6.

52 Memorandum from Legal Section to Chief of Staff, “Deportation of Subversive Aliens”, op.cit., p. 1.

53 See Watt, When Empire Comes Home, op.cit., p. 95.

54 Kim op.cit., p. 263.

55 “CSDIC Translations BCOF – Illegal Entry into Japan 1948”op.cit., p. 46.

56 Memo from Lt. Col., Military Government Liaison Section, to HQ BCOF 29 July 1946. See also Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “An Act Prejudicial to the Occupations Forces: Migration Controls and Korean Residents in Post-Surrender Japan”, Japanese Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, May 2004, pp. 4-28.

57 Imperial Ordinance no. 207 of May 2, 1947, ‘Ordinance for Registration of Aliens’, in GHQ-SCAP Records, Box 2198, folder 16, ‘Immigration’ Feb. 1950-Mar. 1952, microfilm held in National Diet Library, Tokyo, fiche no. GS(B)-01603.

58 Ibid.

59 Eiji Takemae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (trans. Robert Ricketts and S. Swann) (London, Continuum, 2002) p. 451.

60 See for example Brindiv Fortnightly Intelligence Review for fortnight ending 21 January 1946, part 2, p. 2, held in Australian War Memorial, file no. AWM 114, 423/10/63.

61 See for example Nishimura Hideki, Ōsaka de Tatakatta Chōsen Sensō: Suita Hirakata Jiken no Seishun Gunzō, Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2004.

62 See Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan, op.cit., pp. 103-105.

63 Nicholas Collaer, as told to James Neville Miller, “10,000 Miles of Trouble”, Mechanix Illustrated, September 1949, pp. 62-65, quotations from pp. 64 and 75.

64 Memorandum from Legal Section to Chief of Staff, “Deportation of Subversive Aliens”, op.cit. p. 13.

65 Memorandum from the Military Intelligence Section, General Staff to Cief of Staff, “Sentence of Deportation by Occupation Court in Spy Ring Trial”, in GHQ/SCAP Records, Box no. LS-1, folder no. 3, “Top Secret File no. 3”, Jan. 1950-Nov. 1951, held in National Diet Library, Tokyo, microfiche no. TS 00327-00329.

66 Memorandum from Legal Section to Chief of Staff, “Deportation of Subversive Aliens”, op.cit. p. 10.

67 This ordinance was renamed the Migration Control Law after the end of the Allied occupation in 1952.

68 Quoted in ibid., p. 207; see also debate of the Lower House of the Japanese Diet, 28 April, 1952, in Parliament of Japan, Kokkai Kaigiroku Kensaku Shisutemu, (accessed 4 January 2008)

69 See Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Lanham NJ, Rowman and Littlefield, 2007; also Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan, op. cit., pp. 197-222.

70 Heo, Cheju Yonsan, op.cit., p. 123.