North, Iran-Contra, and the Doomsday Project: The Original Congressional Cover Up of Continuity-of-Government Planning

Peter Dale Scott

If ever the constitutional democracy of the United States is overthrown, we now have a better idea of how this is likely to be done. That may be the most important contribution of the recent Iran-contra congressional hearings.

— Theodore Draper, “The Rise of the American Junta,” New York Review of Books, October 8, 1987.

In 1989 I published the following article, “Northwards without North: Bush, Counterterrorism, and the Continuation of Secret Power.” It is of interest today because of its description of how the Congressional Iran-Contra Committees, in their investigation of Iran-Contra, assembled documentation on what we now know as Continuity of Government (COG) planning, only to suppress or misrepresent this important information in their Report. I was concerned about the committees’ decision to sidestep the larger issues of secret powers and secret wars, little knowing that these secret COG powers, or “Doomsday Project,” would in fact be secretly implemented on September 11, 2011. (One of the two Committee Chairs was Lee Hamilton, later co-chair of the similarly evasive 9/11 Commission Report).

|

Oliver North at Iran-Contra Hearings |

Recently I have written about the extraordinary power of the COG network Doomsday planners, or what CNN in 1991 described as a “shadow government…about which you know nothing.”1 Returning to my 1989 essay, I see the essential but complex overlap between this Doomsday Committee and the Iran-Contra secret “junta” or cabal described by Theodore Draper and Senator Paul Sarbanes within the Reagan-Bush administration.

The original article provides detailed information that draws attention to what we have since come to know as COG planning or the Doomsday project, and documents the use of “terrorism” as a pretext to justify it and other abuses of constitutional government.

Specifically, the article demonstrates how North and George H.W. Bush (a far more central figure) used the rubric of “counterterrorism” to

a) fight an undeclared proxy war against Nicaragua in defiance of congressional opposition

b) plan for massive warrantless detention

c) create a special network for developing policies at odds with official White House policies (notably the sale of arms to Iran)

d) use publicly generated funds to defeat opponents of the Contra proxy war in Congress

e) use publicly generated funds to propagandize the American people

f) use publicly generated funds to interfere with a witness to real Contra terrorism

g) falsely claim that the witness himself was a terrorist

h) cover up contra drug trafficking and thwart Senator Kerry’s investigation of this.

Not all of these excesses can be alleged of the surviving COG Committee after Iran-Contra. But one is extremely relevant to what happened on 9/11: the plans for massive warrantless detention. Also relevant is the protection of drug traffickers who were both active terrorists and CIA assets.

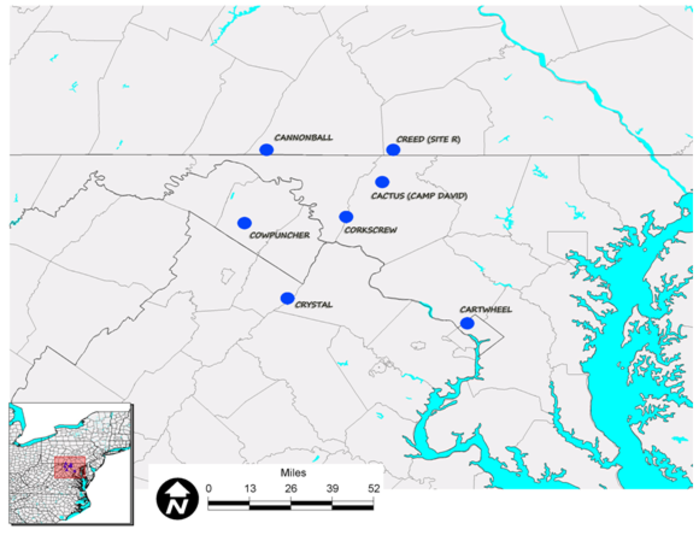

|

Presidential Emergency Facilities. Map by David S. Rotenstein |

The article quotes from two relevant parts of Oliver North’s testimony to the Select Committees. In the first, North explains why he (and other forces in government) were so obsessed with on-going plans to detain large numbers of anti-war protesters: “In Vietnam … we won all the battles and then lost the war …. I would also point out that we didn’t lose the war in Vietnam. We lost the war right here in this city.” My article points out that North was not alone in this obsession:

North was speaking for a large consensus among both policymakers and Cold War academics who believe that “the most pressing problem is not in the Third World but here at home in the struggle for the minds of people.”2 His complaint also echoed that of the French colonels who believed (in the words of a sympathetic American observer) that “France was not defeated in Algeria; de Gaulle chose to retreat.”3 This belief in France led the [resentful] colonels, almost all of whom were veterans of political warfare in the colonies, to direct government funds into “parallel hierarchies” for the manipulation of political opinion in the home country. That practice was uncomfortably close to the use of government funds by North, Carl Channell, and Richard Miller via the Channell-Miller network (and with the support of rightwing contributors and North’s Office to Combat Terrorism), in their attempt to elect a Congress more willing to vote for contra aid.4

(In the decade and a half since Iran-Contra, the use of government funds to target congressional opponents has been replaced by another practice: the outsourcing of government contracts to Private Military Companies and Private Intelligence Companies who then channel some of the funds to elect pro-war congressional supporters and defeat their critics.)5

The second excerpt from the North Hearings concerned North’s role in COG planning:

On July 5, 1987, the Miami Herald reported that North “helped draw up a controversial plan to suspend the Constitution in the event of national crisis such as nuclear war, violent and widespread internal dissent, or national opposition to a U.S. military invasion abroad.” The plan allegedly envisaged the round-up and internment of large numbers of both domestic dissidents (some 26,000) and aliens (perhaps as many as 300,000-400,000) in camps such as the one in Oakdale, Louisiana. …

In the televised Iran-Contra Hearings, North was asked by Congressman Brooks to discuss the alleged contingency plan to suspend the American constitution. Senator Inouye, the committee chairman, twice intervened, ruling that the question was “highly sensitive and classified,” and should only be discussed in executive session. The next day North told Senator Boren, a much more pliant questioner, that to his knowledge the United States had no such plan “in being,” and that he had not participated in [creating such a plan].6

We now know that North’s carefully phrased answer to Senator Boren’s carefully phrased question was deliberately misleading. COG planning continued without interruption, until it was finally implemented on 9/11.

Drawing in part on the extensive supplementary exhibits to the superficial Iran-Contra Report, my article was able to point to the mechanism whereby so-called counterterrorism planning could be used to mask a number of unrelated activities, some of them clearly illegal:

By creating a counterterrorism network with its own secure system of intelligence communications, channels were created from which bureaucrats with opposing viewpoints could simply be excluded. The counterterrorism network even had its own “special worldwide antiterrorist computer network, codenamed Flashboard,” by which members could communicate exclusively with each other and with their collaborators abroad [to the exclusion of their nominal superiors]. Those involved in the Iran arms deals appear to have used “flash” messages on this secure system as late as October 31, 1986.7

Perhaps the most serious limitation to my essay was my misassessment of the secret Iran-Contra cabal as consisting “largely of … middle-level operatives:”

The true cabal appears to have consisted largely of those middle-level operatives brought together by their responsibility for counterterrorism, a group including not only North and Poindexter but also Duane Clarridge and the quintet who moved from developing and reviewing the “counterterrorist” policies with North at the Bush Task Force Senior Review Group to executing them with North through the Operations Sub-Group. (The five were Charles Allen of the CIA, Robert Oakley of the State Department, Noel Koch of the Defense Department, Lt. Gen. John Moellering from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Oliver Revell of the FBI.) Some of these men survived in the Reagan administration unscathed, despite having responsibilities for the Iran-contra affair that would seem at least comparable to North’s.8

My article correctly stressed the centrality of Vice President George H.W. Bush to the group. I was unaware in 1989 that Bush was also directing the on-going Doomsday COG planning project, which continued to meet under three presidents over two decades.9 Nor did I know then that Charles Allen, one of the chief figures in the Iran arms sales scandal, was serving under Bush as the deputy director of the Doomsday project (where a colleague quoted him as saying during a COG meeting, “our job is to throw the Constitution out the window”).10 An advocate as early as 1998 of re-invading Iraq, Allen would rise under President George W. Bush to become Under Secretary for the Office of Intelligence and Analysis at the Department of Homeland Security.

|

G.H.W. Bush 1989 |

Combining what we knew then about the COG planning apparatus with what we know now, I would suggest that we need to discern two different levels of planning (or, if you will, of cabal activity):

1) those at the top, including both Vice President Bush and also figures working outside government, such as Rumsfeld, Cheney, and James Woolsey (future CIA DCI during the Clinton administration);

2) those embedded in the bureaucracy and charged with fleshing out COG plans and other extraordinary secret operations, such as the Iran arms sales. According to the New York Times, “ the project involved hundreds of people, including White House officials, Army generals, C.I.A. officers and private companies run by retired military and intelligence personnel.”11

Both levels availed themselves of their own special communications networks, Project 908 and FLASHBOARD, to avoid accountability to the regular administrative hierarchy.12 Communications personnel for the first secret network were attached to the rarely mentioned White House Communications Agency (WHCA), an agency whose relevance to the JFK assassination and 9/11 I have outlined elsewhere.13 Meanwhile Bush presided over a maze-like series of overlapping restricted groups and agencies with changing names, among which were the National Program Office and the Defense Mobilization Planning Systems Agency, responsible for the various Doomsday initiatives.14

In 1989, citing leaked secret memos, I gave this example of secret planning at the second level:

In June 1986 a new “Alien Border Control Committee” was established, “to implement specific recommendations made by the Vice President’s Task Force on Terrorism regarding the control and removal of terrorist aliens in the U.S.” One of its working groups was charged with conducting “a review of contingency plans for removal of selected aliens.” These 1986 contingency plans “relating to alien terrorists,” which were leaked to the press, “anticipated that the INS may be tasked with … apprehending, and removing from the U.S., a sizeable group of aliens,” and again called for housing “up to 5,000 aliens in temporary (tents) quarters” at a camp in Oakdale, Louisiana. As the designated coordinator of counterterrorism in the National Security Council, North would certainly have known of these contingency plans, which appear to be still with us.15

We know now that these contingency plans were formally implemented in September 2001 as the new Department of Homeland Security’s security plan Endgame, a ten-year plan to build detention centers, with annual budget allocations in the hundreds of millions of dollars.16

In short, the detailed information in this 1989 article, though of less interest today with respect to the specifics of illicit arms sales, casts important additional insight on the elaborate COG planning (or Doomsday Project) which, under the decade-long emergency proclaimed in September 2011, has so radically restructured American law and society.

Peter Dale Scott, a former Canadian diplomat and English Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, is the author of Drugs Oil and War, The Road to 9/11, The War Conspiracy: JFK, 9/11, and the Deep Politics of War. His most recent book is American War Machine: Deep Politics, the CIA Global Drug Connection and the Road to Afghanistan.

Other titles by Peter Dale Scott on related themes include:

The Doomsday Project, Deep Events, and the Shrinking of American Democracy (link)

Is the State of Emergency Superseding the US Constitution? Continuity of Government Planning, War and American Society (link)

‘Continuity of Government’ Planning: War, Terror and the Supplanting of the U.S. Constitution (link)

Recommended citation: Peter Dale Scott, North, Iran-Contra, and the Doomsday Project: The Original Congressional Cover Up of Continuity-of-Government Planning, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 8 No 1, February 21, 2011.

The text of the original 1989 article, “Northwards without North: Bush, Counterterrorism, and the Continuation of Secret Power,” follows here.

Notes

1 CNN, November 17, 1991, quoted in Shirley Anne Warshaw, The Co-presidency of Bush and Cheney [Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Politics and Policy, 2009], 162.

2 George Tanham, counterinsurgency expert, at a conference on Low Intensity Conflict; published in Special Operations in US Strategy (Washington: National Defense University Press, 1984), 293. Tanham continued: “We have to have a firm base here in this country that believes in…what the government is doing. But the media are not very helpful….Somehow, we have got to get over the antagonism that developed during Vietnam [and] achieve a more balanced presentation of the news.”

3 Angelo Codevilla Modern France (LaSalle, Ill.: Open Court, 1974), 219. Cf. 213:

By the end of 1957, the battle of Algiers had been very decisively won. All leading revolutionaries were either dead, in jail, or abroad. However, although the governments of the Fourth Republic had given General Raoul Salan full civil and military powers, they had not ceased to criticize the conduct of operations, notably the use of torture in interrogations during the battle of Algiers. More significantly, the constant talk of a search for a negotiated solution angered many in France and nearly all Europeans in Algeria. Most important, the recurring government crises lent an atmosphere of indecision quite inconsistent with the firm policy being pursued on the scene. Angelo Codevilla, a veteran of the Reagan Intelligence Transition Team in 1980, in 2010 authored a tract urging the Tea Party movement to ally itself with the interests of corporations and Rupert Murdoch media figures to overwhelm the intellectual elites of the universities.

4 Iran-Contra Report, 98-99; cf, Kornbluh. (1987: 205-210); Cockburn (1987: 243-245); Earl Deposition, May 15, 1987, 131, 119 (right-wing contributors). Outsourced contractors on the megabucks Bush-North Doomsday Project also kicked back funds to elect sympathetic legislators. See e.g. Tim Shorrock, Spies for Hire: the secret world of intelligence outsourcing (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 292-96.

5 Peter Dale Scott, American War Machine (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2010), 175-92.

6 Oliver North, Taking the Stand: The Testimony of Lt. Col. Oliver North (New York: Pocket Books, 1987), 643; 732-733.

7 Earl Exhibit #3-8, May 30, 1987 (Bates No. N 1823), Iran-Contra Affair, Appendix B, 9, 1144.

8 My essay also describes the importance in the cabal of CIA officer Duane Clarridge and the outsider Michael Ledeen, long of the American Enterprise Institute and presently of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies . Both men went on to become early advocates of U.S. war in Iraq, and have been accused of helping to foist the forged “Yellowcake” documents that falsely implied Saddam Hussein was secretly acquiring weapons of mass destruction (link). Today Clarridge operates his own private network of covert operatives, the Eclipse Group, in Afghanistan (New York Times, January 22, 2011). Both men are unapologetic advocates of U.S. interventions. Clarridge has said, “We’ll intervene whenever we decide it’s in our national security interests to intervene.” Ledeen’s admiring colleague Jonah Goldberg recalled a Ledeen speech in the early 1990s as saying, in effect, “Every ten years or so, the United States needs to pick up some small crappy little country and throw it against the wall, just to show the world we mean business” (National Review, April 23, 2002).

9 In his memoir, Under Fire (New York: Harper Collins, 1991), North describes “my first major assignment at the NSC” as involving the Doomsday contingency plans, adding that this was “where I came to know George Bush.” In contrast, as the ensuing essay notes, Bush in his campaign autobiography, Looking Forward, admitted knowing of the secret trip by North and McFarlane to Tehran, but claimed not to have known of North’s “other secret operations” before November 1986 (George Bush with Victor Gold, Looking Forward: An Autobiography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1987), 242-43). My essay challenges Bush’s claim.

10 New York Times, April 18, 1994 [“deputy director”]: Mark Perry, Eclipse: The Last Days of the CIA (New York: Morrow, 1992), 215 [“out the window”]. Director of Central Intelligence William Webster formally reprimanded Allen for failing to fully comply with the DCI’s request for full cooperation in the agency’s internal Iran-Contra scandal investigation. After failing to have the reprimand lifted through the regular appeal process, Allen retained future DCI James Woolsey [a member of the COG planning committee] as an attorney and was successful in applying pressure to have the reprimand lifted (Perry, Eclipse, 216). Meanwhile, Clair George, the CIA officer whom Allen and his allies needed to circumvent in order to arrange the arms sales, was convicted in 1992 of felony charges of perjury for lying to Congress, which might have sent him to prison for ten years (George was pardoned by President George H.W. Bush before sentencing occurred). Thus eventually the supervisor of the Iran arms sales was promoted; the man who was seen as an obstacle to it was convicted.

11 Tim Weiner, New York Times, April 18, 1994: “In the Reagan Administration, the project was supervised by Vice President George Bush. A senior C.I.A. officer, Charles Allen, was deputy director. In the Reagan and Bush Administrations, the project involved hundreds of people, including White House officials, Army generals, C.I.A. officers and private companies run by retired military and intelligence personnel.”

12 Shirley Anne Warshaw, The Co-presidency of Bush and Cheney (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Politics and Policy, 2009), 162; Shorrock, Spies for Hire, 77-80, 292-96 (Project 908); Newsweek, October 21, 1985, 26 (FLASHBOARD).

13 David S. Rotenstein, “The Undisclosed Location Disclosed: Continuity of Government Sites as Recent Past Resources,” Historian4Hire.net, July 15, 2010, link. I discuss the important role of the secretive WHCA in both the JFK assassination and the implementation on 9/11 of COG in The Road to 9/11, 228-29; cf. Peter Dale Scott, The War Conspiracy (2008), 31n102.

14 Shorrock, Spies for Hire, 78-79. The Bush-North “Crisis Pre-Planning Committee,” referred to in the ensuing essay, would appear to have had Doomsday responsibilities as well.

15 Memos of September 15, 1986, and October 1, 1986 from Immigration and Naturalization Service Assistant Commissioner Robert J. Walsh, quoted in Mideast Monitor 4,4 (1987: 2). The ABCC was formally established on June 27, 1986, by former Deputy Attorney General D. Lowell Jensen.

16 Peter Dale Scott, The Road to 9/11 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 240.

Northwards without North: Bush, Counterterrorism, and the Continuation of Secret Power

Media concern with the Iran-contra affair vanished suddenly in the spring of 1988, as soon as it became clear that Vice President George Bush, one of the dramatis personae, would become his party’s presidential candidate.1 On the surface of it, the Iran-contra controversy might indeed seem to have subsided. U.S. arms sales to Iran appear to have ceased. Overt military aid to the contras now appears a remote possibility, although we should not forget that its successor, “humanitarian assistance,” was exactly what Oliver North called the arms he was supplying to the contras via the Richard Secord Enterprise in 1985-1986.2 Above all, President Bush — as if sensitive to revelations about his once solid support for the Iran arms sales — has selected a more pragmatic inner council for his administration, from which his former staff on Iran-contra matters (Craig Fuller and Donald Gregg) have been surprisingly excluded.

And yet there is a disturbing institutional legacy from the Iran-contra era of flagrant abuses of covert power. This is the secret counterterrorism apparatus that in 1985-1986 was assembled, under the auspices of then Vice President Bush, and which became the vehicle for Oliver North’s extraordinary influence within the government. With the worldwide decline in the number of private terrorist incidents, there is even more reason to review the counterterrorism apparatus mounted by the Reagan administration against them, in which the key coordinator in the National Security Council (NSC) was Colonel Oliver North. The 1987 congressional investigation of Colonel North’s activities revealed in passing how North and his counterterrorism associates in other agencies abused the secret institutions of this counter-terrorism apparatus to bypass responsible Cabinet members and further the controversial Iran arms sales.

Not all of these abuses ended with the Iran-contra disclosures and the departure of Oliver North. In particular, the abuse of counterterrorism powers in embarrassing domestic critics of the administration’s policies continued, and is all the more alarming because of the Iran-Contra Select Committees’ pointed refusal to pursue evidence of it. The harassment of domestic critics as “terrorists” is a story closely related to the story of Iran-contra. The two stories involve the same institutions, above all North’s Office to Combat Terrorism and the related interagency Operations Sub-Group, both of which were instituted in 1986 as a result of Vice President George Bush’s Task Force on Combating Terrorism.

The Iran-Contra Select Committees came upon flagrant evidence that North had used the powers coordinated by the Operations Sub-Group to harass a domestic critic, Jack Terrell, who had denounced to the FBI illegal gun-running and drug-trafficking by the contra support network. The committees, dominated by a solid bipartisan majority who favored contra support, refused to allow questions to a North-Secord employee on this subject, and even suppressed a crucial document that strongly indicated illegal interference with a federal witness. Like the mainstream press, the committees focused narrowly on the responsibilities of those already departed from the Reagan White House: North, Poindexter, McFarlane), and played down the role of North’s counterterrorism associates who are still in office.

This article will attempt to do what the committees failed to do: to look at the abuses, not of departed individuals, but of secret counterterrorism institutions which are still in existence. Until these abuses are publicly understood, there is the risk that they will continue, and that the nation will continue to drift.

The Iran-Contra Report, Bush, and Domestic Repression

Since the publication of the Report of the Congressional Committees Investigating the Iran-Contra Affair (hereafter Report), there have been signs of a movement away from an incipient constitutional crisis towards a more bipartisan foreign policy, particularly in East-West relations. But there is no reason to celebrate these changes as signaling an end to this country’s recent experience of government by secret networks, with their erosion of constitutional checks and balances. On the contrary, the North-Secord Enterprise’s dealings with convicted drug-traffickers, and its use of dirty tricks against domestic critics of the contra support policy (using procedures established to fight terrorists) have been systematically understated or ignored by Congress. As a result, the rest of the counterterrorism network, who with North ran the Iran and Contra operations, have mostly gone unpunished.

Given the eagerness of Congress to infringe civil liberties in its anti-drug legislation, the failure of the congressional Iran-contra Report to denounce either the North-Secord use of drug-traffickers or their harassment of domestic whistle-blowers was particularly alarming. By their active suppression of documents dealing with drug-trafficking and domestic harassment, the committees made themselves complicit with the administration’s defense of the status quo in these areas.

Thus, however benignly we construe their intentions, the House and Senate committees may have created a new crisis of credibility in the place of an old one, a crisis for Congress as well as for the administration. That a solid majority within the two committees was in support of contra aid (16 out of 27 had voted for it) may explain their failure to weaken the secret powers which North and the FBI were using against critics of the contra support policy.

The contents of the Report suggest that it was written to appease the moderate faction of the Republican Party, and specifically the three East Coast Republicans (Senators Rudman, Cohen, and Trible) who joined with the majority. Others have remarked that the Report touched very lightly on Vice President Bush’s involvement in the Iran-contra affair.3 It is important to note also that the Report barely mentions the central role in the Iran-contra affair of two counterterrorism groups for whose creation the vice president was responsible: North’s own Office to Combat Terrorism, and the concomitant interagency Operations Sub-Group.4

Bush in the second half of 1985 was head of the Vice President’s Task Force on Combatting Terrorism. On January 20,1986, following the report of that Task Force, National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) No. 207 institutionalized North’s role as coordinator of the administration’s counterterrorist program, and supplied him with a secret office and staff (the Office to Combat Terrorism) that was unknown to some other members of the National Security Council.5 Though they seem to have worked chiefly on the Iran arms deals and contra supply operation, North and his two staffers Robert Earl and Craig Coy (both of whom came from the Staff Working Group of Bush’s Task operated at the heart of a whole complex of controversial secret operations in 1986. Earl himself testified that he spent between one-quarter and one-half of his time on Iran matters; his colleague Coy “knew everything … about Democracy Incorporated” (the contra support operation).6 Earl and Coy also the minutes of another important creation of the Task Force and NSDD 207: the interagency Operations Sub-Group (OSG).

Bush and the Administration’s Determination to Continue North’s Non-Iran Operations

This explains why the president, when he admitted in March 1987 that the arms sales to Iran were a mistake, asked Bush to reconvene his Task Force “to review our policy for combating terrorism and to evaluate the effectiveness of our current program.”7 Having been asked, in effect, to evaluate his own creation, Bush’s public response in June 1987 was predictable: “our current policy as articulated in the Task Force report is sound, effective, and fully in accord with our democratic principles and national ideals of freedom.”8 I am told that secretly the Task Force ended the extraordinary procedure whereby counterterrorism officers from various departments could initiate actions in the OSG without consulting their superiors in the Cabinet. Such a change would indeed address the bureaucratic concerns of North’s superiors, but not the civil liberties concerns of the general public.

Bush’s public finding was truly ominous. The depositions given to the Select Committees by Earl and Coy revealed that the Office to Combat Terrorism had rapidly become the means whereby North could coordinate not only the Iran arms sales and the contra supply operation, but also the domestic propaganda activities of Carl “Spitz” Channell and Richard Miller, the closing off of potentially embarrassing investigations by other government agencies (that “might ruin a greater equity of national security”), and the handling for the White House of right-wing contributors to illegal contra arms purchases.9 NSDD 207 and the subsequent Finding of April 1986 had also authorized the kidnapping of international terrorists, one of the more controversial covert operations powers enacted by the Reagan administration.10 And the Operations •Group, another creation of NSDD 207, had been used to harass a whistle-blower, Jack Terrell, who had threatened the survival of the North-Secord “Enterprise” by telling the FBI about contra supply illegalities, such as gun-running and drug-trafficking.

Thus the Bush people in the Reagan administration, having first used North and then acquiesced in his departure, would appear to have approved the continuation of most of his secret political activities in the name of combating terrorism; they denounced only “the mistakes involved in our contacts with Iran.” (These “caused a temporary reduction in credibility which has been regained as our resolve has become apparent.”) In concluding his 1987 review, Bush not only endorsed the achievements of the apparatus which North put together, but also declared that we must “do better.”

It is not surprising that the Vice President’s Task Force should so exonerate the extraordinary abuses of power committed by the counterterrorism apparatus which it set up. To an extraordinary extent, the men at the center of that apparatus were drawn from the Senior Review Group of the Task Force itself. That they should have been reconvened to evaluate what changes were needed was a sure sign, if one were needed, that the Republicans were determined to resist any pressures for significant change.11

The Counterterrorism Cabal and Its Survival

What we have seen in recent years, according to Theodore Draper and Senator Paul Sarbanes, is government by a secret “junta” within the administration.12 Inasmuch as the primary meaning of “junta” is a group joined for the public exercise of power, that term may strike some as unduly alarmist, or at least premature. But a group operating secretly, and at cross purposes with other officials in the same administration, there certainly was. I shall refer to this group not as a “junta,” but rather as a cabal.

At what level did this cabal operate? It was apparently not at the level of Reagan and those in the Oval Office, who had little sense of what was going on. Nor was it restricted to North and Poindexter, who were the expendable executors of the cabal’s strategy. The true cabal appears to have consisted largely of those middle-level operatives brought together by their responsibility for counterterrorism, a group including not only North and Poindexter but also Duane Clarridge and the quintet who moved from developing and reviewing the “counterterrorist” policies with North at the Bush Task Force Senior Review Group to executing them with North through the Operations Sub-Group. (The five were Charles Allen of the CIA, Robert Oakley of the State Department, Noel Koch of the Defense Department, Lt. Gen. John Moellering from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Oliver Revell of the FBI.) Some of these men survived in the Reagan administration unscathed, despite having responsibilities for the Iran-contra affair that would seem at least comparable to North’s.13

Robert Oakley, for example, was in 1985-1986 the State Department expert on counterterrorism. In this capacity he served first on the Bush Task Force Senior Review Group, and then co-chaired the Operations Sub-Group (OSG) with North until about July 1986. He then resigned from the administration, allegedly because (as a Shultz loyalist) he disagreed with North’s Iran arms sales policy. One of National Security Advisor Frank Carlucci’s early acts of post-Iran-contra housecleaning in 1987 was to bring Robert Oakley back from private life to the National Security Council.

By establishing a special apparatus to combat terrorism, the Reagan administration, and the Bush Task Force in particular, created an ongoing network able to bypass normal channels and proceed with an Iran arms sales policy that was opposed by both Secretary of State Shultz and Secretary of Defense Weinberger, as well as by the area desk officers in their respective departments and in the CIA. It is noteworthy that the Iran arms deals with Manucher Ghorbanifar, although they had been proposed as early as November 1984, were blocked until the Bush Task Force on Combating Terrorism began to operate in July 1985. Thereafter the arms deals were handled by a number of bureaucrats whose common denominator, and whose means of communicating directly with each other, was their responsibility for counterterrorism, (These men were Michael Ledeen, Charles Allen, Duane Clarridge, Robert Oakley, plus Oliver North for the United States; and Amiram Nir for Israel.) By creating a counterterrorism network with its own secure system of intelligence communications, channels were created from which bureaucrats with opposing viewpoints could simply be excluded.14 The counterterrorism network even had its own “special worldwide antiterrorist computer network, codenamed Flashboard,” by which members could communicate exclusively with each other and with their collaborators abroad.15 Those involved in the Iran arms deals appear to have used “flash” messages on this secure system as late as October 31, 1986.16

Though the group operated as a cabal, I believe it would be wrong to see it as a conspiracy. Rather, the cabal was created as an arrangement which suited all parts of the administration, including those who preferred to have no responsibility for a policy (selling arms to Iran) which they could not bring themselves to support. This consensual sidestepping of responsibility (or what we might call “guiltlessness by dissociation”) was not even limited to the administration. By their inattention to North’s end-run around the Boland Amendment, congressional leaders had also communicated the message that they did not really care very much about North’s covert law-breaking, as long as they themselves did not have to be called to account for it. As Senator Kennedy noted, it was clear by the end of 1984 “that President Reagan has decided to keep his secret war in Nicaragua going no matter what Congress says or does.”17 Yet Congress, far from reaffirming its budgetary and war-making powers, merely found face-saving ways to adjust to this state of affairs.

To recognize that the cabal was tolerated as a form of in-house deniability (a “divorce of convenience”) is not to diminish the importance of the counterterrorist network’s law-breaking, still less of the Task Force that helped to institutionalize it. A brief review of the end-runs resorted to by the counterterrorist network will remind us that the responsibility for violating law and procedure cannot be restricted, as the Select Committees’ Report would have us believe, to those who have left the government.18 On the contrary, we need to recognize that abuses occurred which are still in need of correction.

The Counterterrorism Network and Iran in 1985

The workings of this counterterrorist network were particularly dramatic at the time of the two Findings (in December 1985 and January 1986) that brought the United States into the prohibited business of arms sales to Iran. Clair George, the CIA Director of Operations and the man who sent out a “burn notice” prohibiting CIA dealings with Ghorbanifar, testified how CIA Director William Casey (the one senior bureaucrat who favored the initiative) bypassed him by having Charles Allen, the National Intelligence Officer for Counterterrorism, deal with Ledeen and Ghorbanifar on “terrorist” matters.19

Casey and North also by-passed George by tasking Allen directly for secret intelligence on Ghorbanifar and his Iranian contact in September 1985, and restricting this intelligence to four men (Casey, North, McFarlane, and Vice Admiral Moreau) who favored the arms sales, thus excluding Shultz, Weinberger, and members of the Operations Directorate.

Mr. Kerr [Committee Counsel]. Can you give me an understanding, if you have one, of why it was that Colonel North in September of 1985 looked to NlO Allen for this type of assistance as opposed to going through the Agency to its Operations Directorate and asking you to do that?

Mr. George. He didn’t want us to know about it.

Mr. Kerr. Do you have any understanding today as to why he didn’t want you to know about it?

Mr. George. I think they were going to run an operation on their own….. Our reaction was going to be this won’t work, but the White House was already working it….. I’m running around saying, hey, here is my burn notice, this guy is a loser, and, Christ, he is working with the Government of Israel, he has already arranged … the November flight or was an intermediary and I’m running around saying we don’t want to work with him when two major countries, the Government of Israel, a close ally and ourselves are still working with him.20

The committees’ Report accurately depicted the consequences of this maneuver:

Denied access to the intelligence, the State Department was not told of the Israeli TOW shipment, was not advised of the linkage of Weir’s release to arms shipments, and was not informed of the President’s decision or the U.S. Government’s involvement (R 169).

It did not, however, explain that this end-run was achieved by going through counterterrorism channels, or that Ghorbanifar’s case officer at this time was North’ s counterterrorism consultant, Michael Ledeen.21

At the time of the November HAWK shipment, what the committees’ Report called McFarlane’s “NSC subordinates” once again “took steps to keep the Department of State hierarchy in the dark about the complex diplomatic problems caused by the operation” (R 178). Once again (though the Report did not say this) counterterrorism channels were used to avoid normal channels.

Robert Oakley, the State Department’s Director of the Office of Counterterrorism and Emergency Planning, authorized North, the NSC counterterrorism expert, to have the U.S. Embassy in Lisbon assist in obtaining clearances for planes carrying the HAWKs from Israel to Iran (R 181). At the same time, Char1es Allen, the CIA’s NIO for Counterterrorism, approached Duane Clarridge, who would later head up the CIA’s Counterterrorism Task Force.22 Allen showed Clarridge, at North’s request, the specially restricted intelligence on the Ledeen-Ghorbanifar initiative. Clarridge then sent a cable (which soon disappeared) arranging for the CIA Chief in Lisbon to work with Richard Secord, whom North had already sent there to work on the problem.23

The intrigues of North, Secord, Clarridge, and Oakley at this point showed a concern for politics rather than security. The CIA Station Chief in Lisbon cabled to Clarridge that “Copp” (Secord) would phone Washington (North) and ask them to give special authorization to the Mission’s chargé d’affaires:

This was necessary … because the moment we start[ed] putting overt pressure on P[rime] M[inister’s] office and F[oreign] M[inister] we opened the very real possibility that the demarche would get back to the [U.S.] Ambassador [Frank Shakespeare, and thus eventually to George Shultz], creating a delicate political problem.24

According to the committees’ Report, Clarridge’s response was to “insure that if the [chargé d’affaires] felt compelled to communicate with the State Department, he should use only the CIA Channel” (R 181). Clarridge’s actual cable shows that the intention was once again to keep matters within the counterterrorism network:

If Charge feels compelled to report any aspects to [nine characters deleted: possibly “Secretary”] request that he send his messages through [deleted] channels and we will ensure that they get to Ambassador Oakley [State’s Counterterrorism Chief].25

Later, in December, North and an Israeli official met with Assistant Secretary of Defense Richard Armitage, whose deputy Noel Koch was a member (with Oakley and Allen) of the Senior Review Group of the Vice-President’s Task Force on Combating Terrorism. Armitage told North “that Secretary Weinberger would be ‘appalled’ if he knew North was dealing with Iranians”; nevertheless, he authorized his subordinates to prepare a plan to replenish the missile stocks drawn down by Israel in the arms sales, and he “kept the sole copy [of the plan] in his office safe” (R 194).

The chief subordinate so authorized was apparently Armitage’s deputy, Noel Koch, who met with North, Secord, and Charles Allen at a February 1986 meeting on the delivery of TOW missiles to Iran, and was later one of three people from Defense listed by North on his short list of “People who know.” (The other two were Secretary Weinberger and Colin Powell, who later became Reagan’s National Security Advisor.)26 By this time Koch (and his military counterpart Lt. Gen. Moellering) had moved along with Oakley and Allen from the Task Force Senior Review Group to the Operations Sub-Group. Duane Clarridge joined them there in February 1986.

The Counterterrorism Network and Iran in 1986

The counterterrorism end-run was used again in January 1986. After Ghorbanifar failed his polygraph test, Clair George

disseminated a notice saying the CIA would do no more business with Ghorbanifar. Ghorbanifar’s polygraph failure, however, did nothing to squelch his relationship with Casey and the NSC staff. Indeed North — who “wanted” Ghorbanifar to pass — had braced himself for a negative result. He told Ledeen beforehand that the CIA would make sure Ghorbanifar flunked because they did not want to work with him. Casey, notwithstanding Clair George’s advice to terminate the Ghorbanifar relationship, found a way to deal with Ghorbanifar outside the normal Operations Directorate headed by George. Casey ordered Charles Allen, who was the CIA’s senior antiterrorism analyst, to meet with Ghorbanifar “to determine and make a record of all the information that he possessed on terrorism, especially that relating to Iranian terrorism — just take another look at this individual.” In George’s view, Allen virtually became the case officer for Ghorbanifar [thus replacing Ledeen, who left the Administration after the November arms fiasco]…. Allen spent five hours with Ghorbanifar at Ledeen’s home on January 13 “to assess Subject’s access In Iranian Government leaders” and to obtain information from him on terrorists (R 205).

Four days later the president signed an amended Finding authorizing the “third parties” (Ghorbanifar), a Finding that once again was withheld not only from Congress but from Weinberger and Shultz (R 208-09).27

The paragraph quoted above was the closest the Report came to identifying the counterterrorism network in the administration as the back channel which allowed a policy to proceed while being kept a secret within the administration itself. The Report did not, however, point out the extent to which the counterwork served as a back channel throughout the administration, and not just under Casey inside the CIA. Clair George testified how Charles Allen, in his role as National Intelligence Officer for Counterterrorism, reported directly to Casey, and was allegedly under orders not to share his information with the Operations Directorate,28 A similar exclusion of those not cleared for counterterrorism communications occurred in the State and Defense Departments, and at the National Security Council. Someone higher than Casey must have been responsible for this interagency situation. One suspects that the responsibility will be found in the secret report of the Vice President’s Task Force on Combating Terrorism.

Nor did the report explain that the separate channel for counterterrorist intelligence made it possible to float intelligence estimates (for example, that Iran had ceased its terrorist activities, or was losing the war against Iraq) which the regular U.S. intelligence community would not endorse.29

To sum up, members of the Bush Task Force Senior Review Group used their counterterrorism channels to thwart official U.S. policy and to conceal their activities from their superiors. The Report, while doing a reasonable job of chronicling the “secrecy, deception, and disdain for the law” of “a small group of senior officials” (R 11), went out of its way to ignore the existence of a counterterrorism network that operated through its own institutions, institutions which at least partly still exist.30

This should be a matter of grave concern to those who believe in the open and democratic determination of foreign policy, particularly in matters that could lead to war. Members of the counterterrorism cabal, above all North and Revell, had used the extraordinary powers of the counterterrorism apparatus against domestic opponents of the administration’s Central American policies as well.

The Administration-Select Committee Consensus on the Need to Continue Covert Operations

It is clear that the “Iran-contra affair” was some sort of political or even constitutional crisis. Unfortunately, as in the case of Watergate a decade ago, there was no national consensus on what constituted that crisis, and hence on what must be done to end it. For many outside the government, the true crisis was not the bureaucratic affair but rather the undeclared war (in this case the contra support policy) and the consequent inner divisions in the nation, divisions which explained why the secret intrigues had taken place. There were few spokesmen for such a view in the committees. On the contrary, it can be said that the committees focused on the bureaucratic dysfunctions (North’s deceit of his colleagues) much more than on the constitutional crisis (North’s deceit and manipulation of the public).31

The televised hearings of the Iran-Contra Select Committees focused very narrowly on the Iran arms sales and the diversion of some of the concomitant profits to the contra cause. Like the previously issued Tower Commission Report, they conceptualized the crisis as a problem of cowboy bureaucrats “out

of control,” and thus suggested that individuals, rather than institutions, contributed to the erosion of constitutional checks and balances, individual freedoms, and democratic process. Further, they zealously honored the administration’s decision that the counterterrorism apparatus deserved to remain classified when documents were censored for release to the public.

Thus the Select Committees’ Report, like its televised hearings, tended to perpetuate the myth that the crisis has disappeared with the departure of Oliver North from the White House. The net effect of the Report‘s compromise language was to play down the importance that those members of the counterterrorism network who remained in the Reagan administration had had in the generation of this strategy in the first place.

It is relevant here that a solid majority of the committees (17 out of 26 members) had voted for contra aid; and that (according to House committee chairman Lee Hamilton) every committee member agreed that “we must be able to conduct covert actions.”32 The domestic enemies North so feared had few spokespersons on the Select Committees. Only two Congressmen (Stokes and Brooks) ever raised critical questions about North’s invasions of domestic liberties; and, significantly, both were told that such matters should be considered only in executive session.

At the end of North’s testimony Lee Hamilton, chair of the House committee, gave an extended critique of North’s activities that was much like the critique offered by George Bush. Silent about North’s abuses of domestic power, silent about the waging of a secret contra war in the face of congressional prohibition and popular disapproval, Hamilton focused, like Bush, on the credibility problem raised by the Iran arms sales: “This secret policy of selling arms to Iran damaged US credibility.”33

Hamilton’s restricted window of disagreement with North was defined by his affirmations of agreement:

There are many parts of your testimony that I agree with. I agree with you that these committees must be careful not to cripple the President. I agree with you that our government needs the capability to carry out covert actions. During my six years on the [House] Intelligence Committee, over 90 percent of the covert actions that were recommended to us by the President were supported and approved.34

With this explicit agreement on the need to continue covert operations, many of which (especially those in Angola and Afghanistan) had support arrangements entangled with North’s Iran-contra “Enterprise,” the committees mostly averted their eyes from the broader extent of the North-Secord power apparatus; and they suppressed or delayed release of important documents relating to it. The Report reflected the Bush-North-Hamilton consensus: it too faulted the Iran arms sales for undermining U.S. “credibility with friends and allies” (R 12); and it found fault not with covert operations, but rather with “covert policies” that were “a perversion of the proper concept of covert operations” (R 17).

Because North used both the Enterprise and counterterrorism apparatus for the harassment of one of his domestic critics, Jack Terrell, we shall do what the committee did not: reconstruct from the public record what little is known of North’s and Bush’s collaboration in the area of domestic repression, including the contingency plans developed by North, under Bush’s auspices, for the round-up and deportation of “terrorist aliens.”

Bush, North, and the Development of Secret Domestic Powers

The little-noticed secret relationship between North and the Office of the Vice President went back at least to 1982, when North was the NSC staff coordinator for crisis management. Bush at that time was charged by NSDD No. 3 of 1981 with responsibility for crisis management, and had been reported by the New York Times to be leader of a Cabinet-level Crisis Management Committee.35 North’s secretary, Fawn Hall, joined him in February 1983, and the two then worked on the development of a secret Crisis Management Center.36 (North also met with members of the Office of the Vice President on such related committees as the Crisis Pre-Planning Committee and the National Security Planning Group.)

There has been much debate as to what this first phase of North’s work on crisis management involved. On July 5, 1987, the Miami Herald reported that North “helped draw up a controversial plan to suspend the Constitution in the event of national crisis such as nuclear war, violent and widespread internal dissent, or national opposition to a U.S. military invasion abroad.” The allegedly envisaged the round-up and internment of large numbers of both domestic dissidents (some 26,000) and aliens (perhaps as many as 300,000-400,000) in camps such as the one in Oakdale, Louisiana.

These contingency plans are particularly alarming in the light of revelations that the FBI had since 1981 “conducted extensive surveillance hundreds of American citizens and groups opposed to the Reagan administration’s policies in Central America”; and that it may have conducted at some of this surveillance under the more permissive guidelines which governed “cases of suspected international terrorism.”37

The FBI’s industry in identifying political dissenters seems much more ominous in the light of concomitant contingency plans to round such dissenters up.

In the televised Iran-Contra Hearings, North was asked by Congressman Brooks to discuss the alleged contingency plan to suspend the American constitution. Senator Inouye, the committee chairman, twice intervened, ruling that the question was “highly sensitive and classified,” and should only be discussed in executive session. The next day North told Senator Boren, a much more pliant questioner, that to his knowledge the United States had no such plan “in being,” and that he had not participated in it.38

Although North’s answers to Boren’s carefully phrased questions appear to be technically correct, they are very misleading. A later report revealed that a draft executive order giving the president broad emergency powers during a severe crisis had indeed been submitted through North to the National Security Council in May 1984. The order contained provisions for “alien control” and “the detention of enemy aliens.” The then Attorney General, William French Smith, disclosed in 1987 that his opposition had killed the proposa1.39

Nevertheless, the institutional relationship between Bush and North continued to evolve, and did eventually result in similar proposals that are still operative, as well as in secret powers which North used against at least one domestic critic. This evolution went through many stages.

In October 1983, under the guidance of the Vice President’s Special Situations Group (SSG), North helped draft the National Security Decision Directive which authorized the invasion of Grenada. That winter the two men visited El Salvador, where Bush told local army commanders they would have to cease their support for death squads. North testified to the Iran-Contra Committees that Bush’s action “was one of the bravest things I’ve seen for [sic] anybodv.” Bush has since reciprocated by repeatedly referring to North as a “hero.”40

In April 1984 North drafted another National Security Decision Directive, which created a new counterterrorism planning group (the Terrorist Incident Working Group, or TIWG) to rescue U.S. hostages in Lebanon (and above all the CIA Station Chief there, William Buckley, who had just been kidnapped). North became the chair of the new counterterrorist group. TIWG’s first major on was the October 1985 interception and capture of the hijackers of the Achille Lauro — which gave a big boost to North’s prestige inside the Administration.

In response to the June 1985 hijack of a TWA plane to Beirut, North worked on the release of the hostage passengers, and Bush was chosen to head the longer-term Vice President’s Task Force on Combating Terrorism. As the National Security Council liaison with the Task Force, North drafted a secret annex for its report, in which he institutionalized and expanded his own counterterrorist powers and also made himself the NSC coordinator of all counterterrorist actions.

In January 1986, by virtue of both the Task Force report and of National Security Decision Directive No. 207, North was given a new Office to Combat Terrorism, which was kept secret even from many other NSC members. Two key members of Bush’s Task Force staff, Robert Earl and Craig Coy, moved over to staff North’s new office. Earl and Coy spent much of the next year working on the Iran arms sales and contra support operation, which made it easier for North to travel. While working for North, Earl and Coy were in fact officially attached to the Crisis Management Center, where North had worked in 1983.41 As we have seen, North also became chair of another new Task Force creation, the new interagency Operations Sub-Group. The OSG answered to the TIWG, which was designed to plan bold new pre-emptive measures, such as kidnapping, against suspected terrorists.

In June 1986 a new “Alien Border Control Committee” was established, “to implement specific recommendations made by the Vice President’s Task Force on Terrorism regarding the control and removal of terrorist aliens in the U.S.”42 One of its working groups was charged with conducting “a review of contingency plans for removal of selected aliens.”43 These 1986 contingency plans “relating to alien terrorists,” which were leaked to the press, “anticipated that the INS may be tasked with … apprehending, and removing from the U.S., a sizeable group of aliens,” and again called for housing “up to 5,000 aliens in temporary (tents) quarters” at a camp in Oakdale, Louisiana.44 As the designated coordinator of counterterrorism in the National Security Council, North would certainly have known of these contingency plans, which appear to be still with us.

Bush’s political autobiography, Looking Forward, gave the impression he had only minimal acquaintance with North and the Iran arms-sales initiative. The Vice President acknowledged only two contacts with North: during the Grenada operation, and when he telephoned North from Israel before meeting that country’s top representative (Nir) in the Iran arms deals. He admitted knowing of the secret trip by North and McFarlane to Tehran, but denied knowing of North’s “other secret operations” before November 1986.45

North’s diaries suggest, however, that in this period he was in recurring contact with Bush, Bush’s advisers, and the other members of Bush’s Task Force. From July 1985 to January 1986, when the secret end-run around Secretary Shultz on the Iran arms sales was devised, the available pages of North’s diaries show only one meeting with President Reagan (on October after the capture of the Achille Lauro hijackers). But they show four meetings with the vice president, either alone, or with Amiram Nir, the top Is counterterrorism expert (November 19), or in the presence of Donald Gregg (July 15, September 10, January 28). In addition, there are at least six recorded meetings of North with the Vice President’s Task Force (on July 25, September 16, September 18, October 2, December 11, and January 7).

OSG, the Operations Sub-Group of the older Terrorist Incident Working Group, convened for the first time a few hours after this last reference Task Force on January 7, 1986, the day that Shultz and Weinberger vigorously opposed the Iran arms-sales plan (R 203). OSG-TlWG met twice again that month (January 14 and 31); but its members appear to have been already meeting with North under the title Restricted Terrorist Incident Working Group (RTIWG) on November 6 and 21. Finally, the diaries show at least 14 other meetings with the Task Force’s senior members (Admiral James Holloway, Ambassador Robert Oakley, and Charles Allen), its principal consultant (Terry Arnold), and its staff (Robert Earl, and Craig Coy, who eventually became North’s own staff).46

In his testimony North suggested an even more intimate relationship with Bush. He told the committee that “when my father died, there were three peopIe in the government of the United States that expressed their condolences.” Two of these were Admiral Poindexter and William Casey, his top bosses in the Iran-contra covert operations. The third “was the Vice President of the States.”47

Bush, North, and the Bureaucratic Consensus on the Need to Deal with Domestic Enemies

How seriously should we regard these contingency plans? Certainly Bush, even in the eyes of his opponents, appears an unlikely candidate to try to rule America by the imposition of martial law. Nevertheless, there is a deep institutional momentum (as opposed to personal impetus) behind the plans to deal with domestic enemies — the same institutional momentum which up to now has also continued to promote the policy of contra support despite widespread disapproval both in this country and abroad.

Absolute powers, once acquired, are seldom willingly surrendered; they are too useful for other purposes. In our present crisis, powers conferred in the name of fighting terrorists have in fact been applied against persons like Brian Willson, whose offense was to issue a nonviolent challenge to the Reagan administration’s contra support policies, or persons like Jack Terrell, who had reported the illegalities of the North-Secord contra support apparatus.

The reluctance of the press or Congress to explore the use of counterterrorism powers against dissenters to the contra support policy is itself a symptom of a national division (like that over Vietnam) that is already too deep for our political processes to resolve easily. The administration and its intelligence apparatus are apparently as determined to maintain those policies as growing numbers of people are to oppose them.

Here it is important to remember that Bush, as a former Director of Central Intelligence, was the original preferred presidential candidate of many CIA employees and veterans in 1980; and that CIA veterans like Daniel Murphy and Donald Gregg were afterwards members of his inner circle. Through the vice president’s responsibilities for three crucial areas of covert operations – crisis management, drugs, and counterterrorism — the CIA veterans around Bush maintained continuous contact with others still inside the agency, such as the CIA’s chief counterterrorism coordinator Duane Clarridge.

Nevertheless, the Iran-Contra Select Committees refused to look at the development of emergency domestic powers against large numbers of aliens, and possibly other opponents of the administration’s war policies. This was an alarming omission. North, at least, believed fervently in the necessity of dealing with domestic enemies.

In response to a friendly leading question from the House Chief Republican Counsel, George Van Cleve, North explained how his Vietnam experience affected his view of the contras:

In Vietnam … in my opinion, we won all the battles and then lost the war …. I would also point out that we didn’t lose the war in Vietnam. We lost the war right here in this city …. We cannot be seen, I believe, in the world today as walking away and leaving failure in our wake. We must be able to demonstrate, not only in Nicaragua, but in Afghanistan and Angola, and elsewhere where freedom fighters have been told “We will support you,” we must be able to continue to do so. If we do not, we will be overwhelmed.48

The logical corollary to such a determined position was indeed that America’s most serious enemies are its domestic ones, and that plans for “victory” in Central America must entail plans for “victory” in Washington, D.C.

North was speaking for a large consensus among both policymakers and Cold War academics who believe that “the most pressing problem is not in the Third World. but here at home in the struggle for the minds of the people.”49 His complaint also echoed that of the French colonels who believed (in the words of a sympathetic American observer) that “France was not defeated in Algeria; de Gaulle chose to retreat.”50 This belief in France led the political colonels. almost all of whom were veterans of political warfare in the colonies, to direct government funds into “parallel hierarchies” for the manipulation of political opinion in the home country. That practice was uncomfortably close to the use of government funds by North, Earl, Coy, Carl Channell, and Richard Miller via the Channell-Miller network (and with the support of rightwing contributors and North’s Office to Combat Terrorism), in their attempt to elect a Congress more willing to vote for contra aid.51

The committees’ response to North’s defiant rationale for domestic repression was to avoid, rather than to explore, the large area where North had been working on just such contingency plans. In his remarks at the end of the North Hearings, Senate committee chairman Inouye noted that he, unlike many of his colleagues on the panel, had voted against aid to the contras; and he quoted eloquently and pertinently from Thomas Jefferson on the right to dissent.52

Yet it was Senator Inouye who, sounding his gavel, told Congressman Brooks that press references to “a contingency plan in the event of emergency that would suspend the American Constitution” touched upon “a highly sensitive and classified area,” and should not be discussed in open session.53 One has the uncomfortable impression that he, and the other veterans of the Intelligence Committees, were only too aware of the updated contingency plans still in place.

North’s Use of the Counterterrorist Network Against a Whistle-blower

It is known that North, with the assistance of FBI Executive Assistant Director Oliver Revell, did use the secret powers of the OSG against a former contra supporter, Jack Terrell, who had begun to report on contra support illegalities to the FBI. In 1986 Terrell’s revelations helped open an investigation by U.S. Assistant Attorney Jeffrey Feldman in Miami into gun-running and drug-trafficking by contra supporters (R 107). Thanks to the new powers conferred on North by the Bush Task Force, copies of the FBI memos were, “because it was an international terrorist matter,” forwarded continuously to North’s office.54 From early on, the Justice Department in Washington injected itself into the Miami investigation (R 107).

Terrell charged specifically that North was linked, through his assistant Robert Owen, to a contra support base in Costa Rica that was owned by an American called John Hull, where both arms and guns were being smuggled. The North-Owen-Hull connection was later amply documented by the Select Iran-Contra Committees (R 106-109), while Terrell’s allegations about drug running at the Hull ranch, ignored and indeed suppressed by the Justice Department and the Select Committees, have been largely corroborated by witnesses (Jorge Morales, Gary Betzner, Werner Lutz) before the Kerry Subcommittee.

North and Owen were concerned to learn in April 1986 that U.S. Assistant Attorney Feldman and an FBI agent from Miami, after interviewing Terrell, had arrived in Costa Rica to interview Hull (R 107-108). Their concern was at least in part personal, because the investigators were passing around a chart that linked North and Owen, through Hull, to a Cuban-American terrorist and suspected drug trafficker called Rene Corvo, who was a focus of the Miami investigation.55 As North knew from the FBI memos forwarded to him, the Miami FBI’s zeal to pursue the Corvo investigation (in contrast to the Washington Justice Department’s later measures to slow it down) derived from the fact that many of the people important in it were extremists involved in earlier terrorist actions, notably the bombing of a Miami bank in 1983.56 Terrell’s own notes and memos from his discussions in Miami, which are largely corroborated by newspaper reports, suggest that the Miami Cuban network around Corvo in the contra supply operation included key members of past intelligence-sponsored terror networks, notably the so-called CORU network which in 1976, when Bush was Director of Central Intelligence, took credit for

Cuban civilian airliner and of former Chilean Ambassador Orlando Letelier.57

North’s concern increased as Terrell began to go public with his charges. When the Christic Institute suit, filed on May 29, 1986, used Terrell’s charges to accuse Hull and Owen of being part of a terrorist conspiracy, North initially asked the FBI to have its Intelligence Division investigate the Christic Institute, along with other aspects of what he, and the FBI, called a “Nicaraguan Active Measures Program” directed against North. He complained in particular about the FBI’s failure to obtain “any information concerning drug charges against North.”58

The FBI “determined that there is a definite association between the dates of the Congressional votes on Contra aide (sic) to the Nicaraguan rebels and the ‘active measures’ being directed against Lieutenant Colonel North.” Nevertheless, the FBI, trying to stay out of a sensitive political fight between the White House and Congress, declined to pursue the matter.59

Then on June 25, 1986, for the first time Terrell aired on the CBS show “West 57th” his charges about the relationship of North and Owen to the John Hull ranch in Costa Rica. By now Richard Secord, who unlike North was a defendant in the Christic suit, was using Enterprise funds to have an investigator, Glenn Robinette, interview Terrell. On July 15, Robinette submitted a memo on Terrell, in which he reported on Terrell’s unpaid relationship to the Christic Institute, and added that Hull’s air strips, according to Terrell, “were used for landings and transfer of military equipment but also drugs.”60 Robinette also transmitted to North excerpts Terrell had given him from a book he was writing, in which he talked about contra discussions of past and future attempts to assassinate the dissident contra leader Eden Pastora.61 (A bomb attempt on Pastora’s life in May 1984, which killed and injured many others, was the central allegation in the charges brought by the Christic Institute.)

At this point the secret counterterrorism powers established by Bush to deal with assassination threats went into high gear to investigate not Hull or Corvo, but rather Terrell the whistle-blower. On the same day, July 15, someone in the FBI “suspected that Terrell might be involved” in an alleged assassination plot: not the plot against Pastora, but the plot, of which it had heard from “a classified source[,] that pro-Sandinista individuals might have been contemplating an assassination of President Reagan” (R 112).62

On July 17, this was conveyed to North by his FBI counterpart on the Operations Sub-Group, Oliver Revell. North met with Robinette the same evening, and told him to take his July 15 memo, along with Terrell’s book excerpts about the alleged plots against Pastora, to Revell at the FBI.63 He also prepared a memo for Admiral Poindexter, calling Terrell a “terrorist threat,” and focusing at the outset on Terrell’s role in the Christic Institute suit.

As a source for this allegation, North noted that “one of the security officers for Project Democracy” (North’s euphemism for the North-Secord “Enterprise” of private companies) had investigated Terrell, and that this “security officer” (Secord’s investigator Glenn Robinette), was meeting that night with the FBI representative to the Operations Sub-Group, Oliver Revell. The memo explained that the FBI “was preparing a counterintelligence/counterterrorism operations plan” against Terrell, “for review by OSG-TIWG tomorrow.” This plan was presumably approved by the OSG, since one week later North reported that the FBI and the Secret Service now had Terrell under “active surveillance.”

Glenn Robinette’s repeated meetings with Terrell in July 1986 had nothing whatsoever to do with terrorism or counterterrorism, but were instead a naked attempt to silence Terrell as a witness. This is clear from a second unaddressed Robinette memo of July 17, 1986, held but not released by the Select Committees, which reported on his efforts to “investigate” Terrell. The memo confirms why the Enterprise was concerned about Terrell: “what he knows … could be embarrassing to R[ichard] S[ecord];” and “Terrell may actually possess enough information … to be dangerous to our objectives.”

The memo corroborates Terrell’s own story that Robinette tried to silence Terrell by offering funds for a proposed helicopter service business in Costa Rica. It recommends that Robinette’s “interest” in this project be increased: “The ‘investors’ would require that he reduce or stop his ‘political talking’ as it would ‘affect our investment.'” The memo concludes that by this means “the chopper or air freight service in Costa Rica” could be “connected to some future non-commercial [covert operations support?] work;” and that “we would have him [Terrell] in hand and somewhat in our control.”64

On the same day, July 17, North also prepared his own memo for John Poindexter, reporting on Robinette’s evaluation of Terrell, but also significantly altering it. Where Robinette had called Terrell an “Operational Threat” (a possible “serious threat to us based on … his previously spoken statements”), North called Terrell a “Terrorist Threat.” Where Robinette had said Terrell “may possess enough information … to be dangerous to our objectives,” North wrote that “one of the security officers for Project Democracy” (Robinette) had evaluated Terrell “as ‘extremely dangerous’ and possibly working for the security services of another country.”65

A later North memo added:

It is important to note that Terrell has been a principal witness against supporters of the Nicaraguan resistance [i.e., of the contras] both in and outside the U.S. Government. Terrell’s accusations have formed the basis of a civil law suit [the Christic Institute’s suit] and his charges are at the center of Senator Kerry’s investigation [of the contra support operation’s alleged involvement in drug-trafficking] in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.”66

North’s memos did not mention what had chiefly concerned his aide Robert Owen: that Terrell’s reports to the FBI about John Hull, Owen, and North had launched an investigation by Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Feldman in Miami. Inasmuch as Terrell had volunteered his information to the FBI, the Justice Department, and a congressional committee, Robinette’s actions and recommendations might appear to constitute improper interference with a witness.

We know from North’s later memos on Terrell that by July 25

the Operations Sub-Group (OSG) of the Terrorist Incident Working Group (TIWG) ha[d] made available to the FBI all information on Mr. Terrell from other U.S. Government agencies. Various government agencies — Customs, Secret Service, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms — have information of some of Terrell’s activities and the FBI is currently consolidating this information for their investigation.

By this date “the FBI, in concert with the Secret Service,” had “Terrell under active surveillance.”67

The FBI Expands the Terrell Investigation to Others

On July 29 and 30 the FBI and the Secret Service polygraphed Terrell for two whole days, after which the FBI “eliminated him as being a threat to the President.”68 Revell reported this to the OSG, adding however that the FBI was still “pursuing other possible areas of investigation.”69

Indeed it was. By now the FBI had put others under surveillance, including two members of the Nicaraguan Embassy, and David MacMichael, an acquaintance of Terrell and vocal critic of contra aid. Robinette had told the FBI on July 17 that he had reached Terrell at the International Center for Development Policy (ICDP), a Washington public interest group which brought Terrell to Washington to be interviewed by the staff of Senator Kerry’s Subcommittee; the FBI now began, apparently through its Terrorist Unit, to investigate the ICDP, and soon reported evidence that the Center was giving Terrell money.70

The FBI’s investigation of the Center continued for some weeks, and least three ICDP employees were interviewed by the FBI about their foreign contacts.71 The FBI’s interest in the Intemational Center for Development Policy appears to have continued after U.S. Attorney Kellner “received a letter from John Hull [on August 27, 1986] making serious allegations of impropriety by members of Senator Kerry’s staff,” which Kellner had brought with him to Mark Richard in Washington on August 29 (R 109). Terrell’s activities at the International Center were central to Hull’s allegations.72 Kellner testified that Hull’s affidavits were “amateurish” and that he did not believe them; nevertheless, his own deposition confirms that the affidavits were investigated.73

Because Terrell had used the Center’s telephones. it seems likely that the electronic surveillance on Terrell expanded into electronic surveillance of the Center itself. In November, when the Hasenfus contra supply plane went down, the Center was burglarized; and the only documents taken were copies of the airplane’s logs that Terrell had been studying there. (Also that fall, the Washington office of four nonviolent Gandhians who were fasting on the Capitol steps was broken into after they too had been designated “terrorists” by the FBI.)

The efforts of North and others to bring pressure on Terrell cannot be described as a failure. When Terrell came to Washington, he prepared for Senator Kerry’s staff a series of memos describing the drug activities of men in the contra support network like Rene Corvo, Felipe Vidal, Norwin Meneses, and Frank Castro.74 None of these names (not even Corvo’s) will be found in the Select Committees’ account of the Rene Corvo investigation in Miami (R 106-109). And none of these names have as yet surfaced in the Hearings of Senator Kerry’s Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Narcotics.

Terrell’s essential credibility as a witness is corroborated by subsequent revelations about the John Hull ranch in Costa Rica, the North-Owen relationship to it, and the belatedly released Robinette memo about efforts to get Terrcll “in our control.” Yet it is he, and not John Hull, who has since been indicted by a Miami Grand Jury, a Grand Jury which ironically was originally impaneled partly as a result of the information about Hull which Terrell gave the FBI (R 109).

In 1988, having been already warned of his impending indictment by the Reagan-Meese Justice Department, Terrell declined, on the advice of counsel, to answer questions when summoned as a witness by the Christic Institute. Deprived of testimony from the man an FBI Teletype once described as a “star witness” in the suit, the Christic Institute suit was thrown out when it came to trial.75

It is hardly surprising that North would use the powers conferred on him to cover up his support operation’s illegalities, and particularly the stories about and assassination plots. What is most surprising is that Congress, despite its professed concern about drugs, also participated in this cover-up. It is clear m FBI Teletypes that Terrell had been interviewed by them about “alleged…smuggling of weapons and narcotics.”76 Yet the Report of the Iran-Contra Committees, as assiduously as North, suppressed every reference to Terrrell’s drug allegations (R 106-08), as well as to the plot against Pastora. It falsely presented Terrell as a self-admitted CIA assassin (R 112); and let it appear that Terrell had been interviewed as a suspect in alleged assassination plots, rather than as a witness (R 116). Thus Congress has so far afforded this whistle-blower no relief.

The Failure of Congress