Contested Waters – Contested Texts: Storm over Korea’s West Sea

Gavan McCormack

The Asia Pacific Journal’s Phantom Text

This is the story of a text, which was briefly posted at The Asia Pacific Journal on 6 February, and almost immediately (within hours) withdrawn. The author was Kim Man-bok, who from November 2006 to January 2008 was Director of the South Korean National Intelligence Service (Korean CIA) under the Government of President Roh Moo-hyun. His text was entitled “Let Us Turn Korea’s West Sea (the Sea of Dispute) into a Sea of Peace and Prosperity.” The Asia-Pacific Journal is not noted for publishing articles by present or former national intelligence chiefs, and so both the posting and then the withdrawal of this text were almost equally unusual.

The text began as a chapter in a book published by the Korean Peace Forum in Seoul in October 2010, and entitled (as translated) “Again, Querying the Path of the Korean Peninsula.” That Korean text was translated into Japanese and published, together with a short postscript added after the South-North clashes and the bombardment of Yeonpyeong Island in November, in the February 2011 issue of the monthly Sekai (published early January).1 Through the good offices of the Sekai editor, the Asia-Pacific Journal in January 2011 sought permission to translate and publish an English version. Author Kim consented, asked for several minor revisions, and the translation proceeded.

That translation was posted on the night of Sunday 6 February, as found here and announced the following day in the Newsletter to subscribers. Almost immediately, however, the Asia-Pacific Journal received word that the author wanted publication to be stayed, and we reluctantly obliged. Many readers were puzzled to receive advice of publication of a text, only to find, rather than a text, an empty page. We hoped the withdrawal of permission would be temporary, and sought author Kim’s understanding to renew the permission he had initially granted, but having no response we are unable to publish the article as it originally appeared. However, given wide public interest both in the matters discussed in the article and in its aftermath (discussed below), and since the main text is already widely circulating in Korean and in Japanese, we therefore provide below a resume, with some extensive quotes.

The reasons for the author’s withdrawal of consent to publish gradually became clear. Just days after the Sekai translation was published, the major Seoul daily Chosun ilbo on 13 January published a fierce attack on Kim.2 Inter alia, it accused him of suggesting the November South-North artillery battle on and around Yeonpyeong Island might have been the consequence of South Korea, under Lee Myung-bak, abandoning the dialogue policy of the previous government; of referring to the outcome of the battle by the “humiliating” expression “South Korea’s defeat;” of offering some justification for the North’s artillery attack (its warnings were ignored); and of rejecting the outcome of the South Korean government’s report on the March incident of the sinking of the naval corvette, the Cheonan. It also accused Kim of publishing details of matters known only to him in his capacity as head of the National Intelligence Service, notably hitherto unknown details of exchanges with North Korean leader Kim Jong-il that occurred late in 2007.

In the face of increasing pressure, the Korean Intelligence Service formally accused him on January 26 of violating its regulations by revealing secrets that he had acquired during his tenure at the agency. Following the accusation, the prosecutor’s office opened an official investigation.

In a follow-up article on 30 January Chosun ilbo widened the attack to the Japanese journal that carried Kim’s text.3 Sekai, published by Iwanami, has a long and controversial record of comment on Korean affairs. Its campaigns against the then Seoul dictatorship and against the oppression, torture and denial of human rights to democratic dissenters, especially during the era of President Park Chung-hee in the 1960s and 1970s, earned it a ban in South Korea that helped raise its reputation among dissenters in South Korea as well as in Japan. Its commentary on North Korea was equally controversial, and Sekai was was one of the few places where North Korean leader Kim Il Sung occasionally appeared, interviewed by the journal’s editor. Korean conservatives cannot forgive Sekai for the stances it then took and Chosun ilbo therefore raises again old accusations of disseminating demagogic and false material. Referring to Sekai (today) as being “pro-North anti-South” and tantamount to a “North Korean propaganda organ,” it reserved its most savage attack for “the anti-South Korean intellectuals such as [Tokyo University emeritus professor and regular Sekai contributor] Wada Haruki as “traitors.” Conservatives in Seoul may also have been outraged that Wada, had just been feted in Seoul as recipient of the 2010 “Kim Dae-jung Prize,” awarded by Chonnam National University for contributions to Korean democracy and peace in the peninsula.

Sekai editor Okamoto Atsushi commented on that journal’s homepage (31 January) that it seemed odd that the Korean prosecutors should pay attention to things published in a Japanese journal, but apparently not to the same views (including the account of the 2007 Summit) that had been published months earlier in Korean.4 He pointed out that the Sekai article contained a short “postscript,” in which Kim does indeed criticize the Lee Myung-bak government’s response to the various peninsular crises culminating in the Yeonpyeong Island artillery exchange, but the only fresh material he introduces there is a brief introduction of some recent Wiki-leaks revelations on Korea (which he states he learned “from the media”). To Okamoto, the charges seemed to signify “oppression of views critical of the Lee Myung-bak government’s policies.” He added that “South Korea since its democratization has earned the profound respect of democratic countries for the free and vigorous expression of opinion. It would be a matter of deep concern if it were now to revert to military government style practices under which once again the state intimidated and oppressed opinion…”

Whatever its eventual outcome, the affair exposed the deep split in the Korean establishment over North Korea policy between those associated with the former, “Sunshine” (or engagement)-oriented governments of Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-Hyun and the current (from 2008) government of Lee Myung-bak. It focused attention on the sharp contrast in the West Sea between the agreements in principle reached in 2007 by the Roh government and the confrontationist policies pursued by the present government under which the artillery barrages of 2010 occurred and full-scale war was narrowly avoided. The extension of the attack from Kim Man-bok himself to an eminent Japanese journal also pointed towards a revival of the Japan-Korea “culture wars” of the 1970s. With Kim Man-bok standing at the centre of this furore, it becomes a “Kim Man-bok affair,” whose outcome at time of writing (mid-February 2011) is far from clear.

In the febrile atmosphere of today’s Seoul, it was not surprising that author Kim should feel reluctant to do anything that might bring down more fire on his head. The charges and the investigation proceed. While Kim has been charged but not yet indicted, his offending text circulates in Korean and in Japanese. Sooner or later it will be in English too, but for the moment all we can do is quote liberally from our translation of the Japanese and draw attention to the Korean and Japanese versions. It is up to readers to figure out what it might be that has outraged important sections of the South Korean national media and then stirred the prosecutors into action.

Kim Man-bok’s Text – To Transform the West Sea

Kim, like many commentators, points to the failure of the post-Korean War settlement to reach any agreement on the maritime border, especially in the west, as the cause of its evolution into a “Sea of Dispute.” What is distinctive about his analysis, however, is the close attention he pays to the efforts he and the Roh government (2003 to 2007) made to solve the problems by a radical and imaginative formula, designed to convert the “Sea of Dispute” into a “Sea of Peace and Mutual Cooperation.” Conservative Koreans, and especially the Lee Myung-bak government, must be presumed to be discomfited, even angry, at Kim’s calling attention to the record of the previous government, and they seem especially outraged that he should choose to publish his critique in Japanese, in that long-term target of conservative South Korean fury, Sekai.

The existing demilitarization line at sea, unlike the line that DML on land, is simply the line that Mark W. Clark, Commander of the UN forces, unilaterally drew on the map on August 30, 1953. It has been known since then either as the “Clark Line”, or the “Northern Limit Line (NLL).” He chose a mid-point between the five West Sea islands of Baengnyeong, Daecheong, Seocheong, Yeonpyeong, and U, then under South Korean control, and the North Korean coast. The line he drew had no international legal status and was distinct from the Armistice agreement of July. The arrangements were provisional, pending formal negotiations to draw up a peace treaty. Those negotiations have yet to take place.

Up until 1973, North Korea crossed the NLL from time to time, but made no particular issue of it. Thereafter, however, it contested it increasingly openly, especially during the fishing season in May and June when the crabs in these seas are especially abundant. However, according to Kim, in the Inter-Korean Basic Agreement of 1992, North Korea agreed to treat the NLL as an “inviolable maritime boundary.” Indeed, the Basic Agreement provided not only that each side shall honor the control actually exercised by the other party within the boundary, but also that they would soon begin consultations toward a more permanent settlement of the dispute. Kim interpreted the Basic Agreement as North Korea’s agreement to honor the NLL as an “inviolable maritime boundary,” an interpretation that one might expect the right to celebrate. That his conservative reading of the agreement was brushed aside and instead his tepid criticism of Lee Myung-bak’s North Korea policy attacked is indicative of the anxieties that wrack conservative Korean politics.

These consultations, promised in 1992, have yet to take place, due at least in large measure to the South’s refusal to discuss the matter. Thereafter, however, despite regular transgressions during crab-fishing season, the North de facto recognized the existence of the NLL.

Under these unsettled conditions, many military clashes, of varying degrees of seriousness, occurred. Following the “first Yeonpyeong naval battle,” on 15 June 1999 (during the crab-fishing season) in which North Korea suffered heavy casualties, the Kim Dae Jung government introduced strict five-stage rules of engagement to try to reduce the possibility of any inadvertent recurrence. North Korea, however, responded by unilaterally declaring its own NLL, a “West Sea Maritime Military Demarcation Line” based on a “12 nautical mile limit principle” that completely cut off the main South Korean islands scattered along its coast (Baengnyeong, Daecheong, Seocheong, and Yeonpyeong). Subsequently, in March 2000, it promulgated new Navigation Regulations requiring that “any US military vessels or South Korean civilian ships entering the region to the north of the military demarcation line must use one or other of the two routes designated by North Korea.”

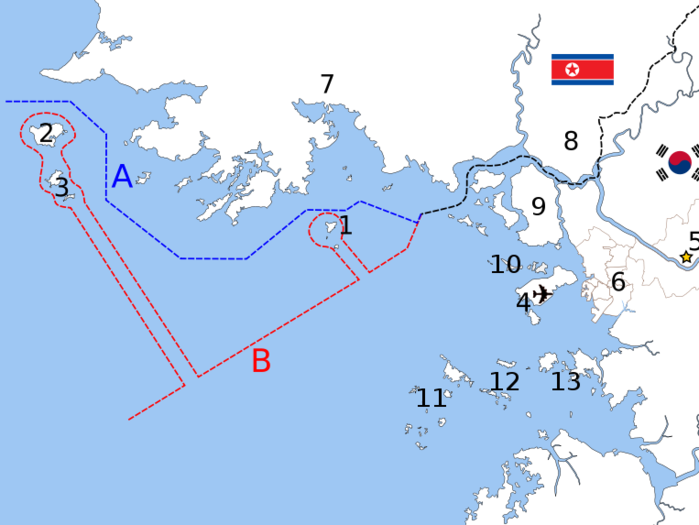

The map below shows the complexity of these two arbitrary lines and the need for South-North agreement on a clear boundary. The March 2010 incident of the sinking of the South Korean corvette Cheonan occurred in the vicinity of Baengnyeong Island and the November 2010 clash on Yeonpyeong Island and its adjacent seas, both deep in contested territory and both within a few kilometers of North Korean shores. The fact that Incheon International Airport and the South Korean capital of Seoul lie just to the south of the contested zone, and the major North Korean cities of Haeju and Kaesong just to its north (with Pyongyang itself just a little further away) shows how risky is the long-term failure to reach an agreement on this border.

The West Sea: Sea of Dispute

A. Northern Limit Line (NLL, the border claimed by South Korea since 1953)

B. Military Demarcation Line (the border claimed by North Korea since 1999

1. Yeonpyeong Island (Site of artillery clash in November 2010)

2. Baengnyeong Island (Site of sinking of Cheonan, March 2010)

3. Daecheong Island (site of Nov 1999 battle)

4. Jung-gu (Incheon Intl. Airport)

5. Seoul 6. Incheon 7. Haeju

8. Kaesong 9. Ganghwa County 10. Bukdo Myeon

11. Deokjeok Myeon 12. Jawol Myeon 13. Yeongheung Myeon

Despite South Korean president Kim Dae Jung’s visit to Pyongyang in June 2000 for a summit meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jung-il, and the adoption of the “June 15 South-North Joint declaration,” a “second Yeonpyeong naval battle” nevertheless took place on 29 June 2002. On this occasion, according to Kim, retaliation for its defeat in 1999 was a strong motivating force in leading North Korea to launch a sudden, surprise attack.

The South-North Korean Agreement of 2007

Prevention of further West Sea naval battles was a policy priority for the Roh Moo-hyun government that assumed office in February 2003. Kim Man-bok, as Roh’s intelligence chief, was a central participant and witness to the South-North exchanges that occurred as a result and therefore his account deserves to be quoted at length.

Between May 2004 and December 2007, at the initiative of the South Korean side, high-level talks between South and North Korean senior military officers were conducted on seven occasions, alternating between locations in the South and in the North. Notably during the second talks between senior military officers of South and North held at Mt Sorak in June 2004, both sides agreed on a common inter-ship radio frequency as a means to prevent accidental conflict. At subsequent South-North talks between senior military officers, both sides agreed on the “establishment of common fishing grounds in the West Sea,” on “direct sea access for North Korean civilian ships to the port of Haeju,” and on “necessary military guarantee measures for South-North economic exchange and cooperation.” …. it was thanks to such measures that placed an emphasis on building military trust, even if at an elementary level, that there was not a single military confrontation along the NLL in the West Sea during the period of the Roh government.

On the basis of adapting and developing the “sunshine policy,” the Roh government proposed a “peace and prosperity policy” as its diplomatic policy for North Korea and Northeast Asia. It was a plan for the peaceful development of the Korean peninsula that combined “peace” at the security level with “prosperity” at the economic level. Even during the period of heightened crisis that followed North Korea’s “nuclear possession declaration” on February 10 2005, the Roh government affirmed the “‘3 No’ principles of policy towards the North: ‘no war on the Korean peninsula,’ ‘no sanctions or blockade of North Korea,’ and ‘no attempt to cause the collapse of the North Korean regime’.” The Roh Moo-hyun government’s peace and prosperity policies bore fruit in the historic “October 4 South-North Summit Declaration,” in which both sides agreed on the establishment of a “West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation” designed to convert the West Sea from a “sea of conflict” to a “sea of peace and prosperity.”

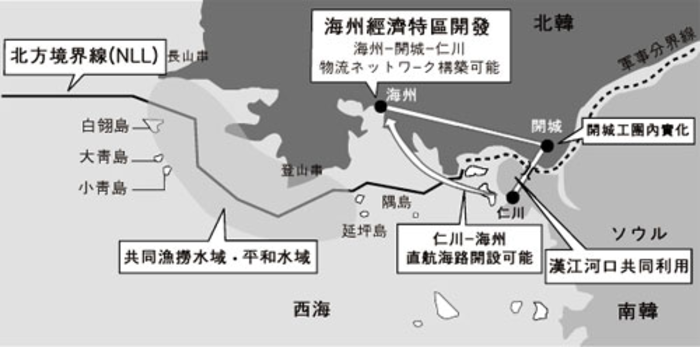

In the fifth article of the South-North Summit Declaration signed at Pyongyang on October 4, 2007, president Roh Moo-hyun and chairman Kim Jung-il agreed that “the South and North would pave the way for a ‘West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation’ in the Haeju region, establish a joint fishery zone and a maritime zone of peace, construct an Economic Special Zone centering on the port of Haeju, allow direct sea access to Haeju for civilian ships, and positively promote shared usage of the Han River estuary.”

From the beginning of August 2007, when agreement was reached to hold the second South-North Summit in Pyongyang between August 27 and 30, 2007, President Roh directed the drawing up of a plan for converting the West Sea, the “Sea of Conflict,” into a “sea of peace and prosperity,” personally collecting data and materials and organizing a series of discussions with related officials. As the summit was postponed to the period October 2-4 due to flood damage in mid-August in North Korea, closer attention was paid to the plan for a “West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation” and a talks strategy was drawn up that included “Draft Items for Agreement at the Summit Plenary” and “Draft Items to be drawn up separately for signature.”

When President Roh Moo-hyun proposed his plan for the “West Sea Special Zone” during the morning session of the Second South-North Summit on October 3 2007, National Defence Commission chairman Kim Jong-il seems to have considered it impractical in light of the existing situation of military confrontation in the West Sea and so evaded discussion by saying, “let the various problems be referred for discussion at the Prime Ministerial level.” In response, president Roh Moo-hyun made greater efforts to press his point, emphasizing its importance from three aspects: first, as the optimal way to resolve possible military confrontation in the West Sea; second, that the West Coast Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation would become the axis of joint South-North prosperity in a future “West Sea Coastal Era,” and third, that not only would it construct peace by ending confrontation in the West Sea but that it was also a comprehensive plan for developing South-North economic cooperation in the West Sea.

|

The South-North Summit, Pyongyang, October 2007. (wearing pink necktie, at far right, is Kim Man-bok) |

At the afternoon session on the same day, Chairman Kim Jong-il welcomed President Roh’s proposal for a West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation, saying, “I discussed the matter over lunch with senior responsible officials of the National Defense Commission. When I raised the possibility of a Haeju Industrial Complex, they replied that that would present no problem. Not only would Haeju itself be fine but Kangryong township, linking Haeju and the Kaesong industrial complex, and Haeju port, could also be developed.”

|

The West Sea: Sea of Peace and Cooperation |

This was, as Kim Man-bok rightly suggests, an extraordinary agreement. The international media at the time, which obsessively focused on the North Korean “nuclear threat,” paid it far too little attention. Under the Agreement, with the joint fishing zone and “marine zone of peace” spanning the NLL, both sides would pull back their forces and replace them by lightly armed police patrols. With Haeju City in North Korea declared a “special economic zone,” (connected to the already existing Kaesong Industrial Zone, and special corridors by land and sea opened to link the major industrial and port zones of South and North, and the undeveloped area of the Han River estuary opened to cooperative development, Kim concluded that

the West Sea coastal area would be transformed from “frontline military confrontation” to “National Economic Community,” thus contributing not only to peace on the Korean peninsula but to the unification that is the deep desire of the Korean people. ….[It would be] nothing short of a complete paradigm shift, transforming the West Sea, a danger zone where there is always the risk of military confrontation, so that South and North come together not in military ways but in terms of permanently reducing tension and establishing peace through economic cooperation and mutual prosperity. The epochal, counter-intuitive quality of the “West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation” lies in the fact that it does not stir up the problem of the maritime borderline but instead develops a mutually beneficial economic system, thus converting a “zero-sum” military game into a “win-win” economic game.

Unfortunately, as Kim recounts, time ran out before the details and procedures to accomplish those goals could be agreed. A Second Round of South-North Defense Ministers Meeting was scheduled to be held in Pyongyang for three days from 27 November 2007 to settle the detailed blueprint of the “West Sea Zone of Peace and Economic Cooperation.” Kim goes on,

However, at the second South-North Defense Ministers’ Meeting, between Deputy Defense Minister Kim Chang-su from the South and Korean People’s Army military affairs Chief Kim Il-chol from the North, it was only possible to come to an agreement in principle “that South and North would adopt military guarantee measures for the West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation. A serious error was made by agreeing to “refer the matter of military guarantees in concrete cases to be discussed and agreed as a matter of highest priority at a separate meeting of South-North working-level military officials.” This is something that will have to be dealt with in concrete terms by the convening of a third South-North Defense Ministers meeting.

Abandonment of the 2007 Agreement and Reversion of the West Sea into a “Sea of War”

The “Third South-North Defense Ministers meeting” has yet to occur. Kim Man-bok is severe in his criticism of the Lee Myung-bak government, not least for abandoning the West Sea cooperation and development agenda. He says,

By reinforcing its exclusive strategic cooperation with Japan and the United States under the US-South Korea alliance, and by taking the lead in resolutions at the United Nations denouncing North Korea on human rights matters, the Lee Myung-bak government has followed a consistent line of containment of North Korea. By linking the North Korean nuclear issue and the South-North Korea relationship, it has also reverted to Cold War policies of confrontation with the North, insisting that “in case of a North Korean pre-emptive nuclear attack being imminent, South Korea would not hold back from a pin-point attack on the North’s nuclear facilities.” In this context, on May 25, 2009, North Korea carried out its second nuclear test, and South Korea the following day declared that it would fully participate in the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI, designed to prevent proliferation of weapons of mass destruction), meaning that South Korean warships might inspect or detain North Korean cargo boats.

On 20 November 2009, another West Sea clash took place. Kim describes this “Daecheong naval battle,” in which North Korea suffered heavy losses while South Korea escaped unharmed, as a “unilateral victory for the South Korean side.” And, although he does not say so, it was taken in Lee Myung-bak circles as vindication for the adoption of a tougher line. Inter alia, the Lee government had drastically simplified the previous government’s five-stage “rules of engagement” based on proportionality and designed to “prevent local conflicts escalating into all-out war” in such a way, according to Kim, as to signal the intention to “make a determined, preemptive attack in the event of any North Korean NLL provocation.” That, he suggests, might be what happened at Daecheong.

Then, on 26 March 2010, in the atmosphere of heightened tension and confrontation that followed the Daecheong Incident, occurred the sinking of the South Korean corvette, the Cheonan. The sequence of events that followed is well known: South Korea insisted that its ship had been attacked and deliberately sunk by North Korea, probably by torpedo; an international investigation conducted by South Korea together with states friendly towards South Korea and the US confirmed that account; doubts over that Report’s methodology and conclusions spread both within South Korea and internationally; North Korea consistently and vigorously denied any involvement, and the alternative (Russian) report (so far known only in resume form) presented a disturbed mine hypothesis. The doubts over the Cheonan have been well discussed in sources that are readily accessible, including in this journal.5 Kim Man-bok notes discrepancies and problems in the Lee Government’s case and finds especially interesting the Russian investigation, with its hypothesis of a mine explosion, but he simply introduces the various schools of interpretation.

He stresses, however, the seriousness of the aftermath,

South Korea suspended aid to North Korea, discontinued relations, and accused North Korea of a “torpedo attack” before the UN Security Council. North Korea responded angrily that, it “had nothing to do with the sinking of the Cheonan.” And it reinforced its confrontation with South Korea by declaring that it would have “no further discussions or contact with South Korea during the presidency of Lee Myung-bak.” With the United States and Japan affirming total support for the findings of the South Korean government’s investigation, while China and Russia supported North Korea, the situation surrounding the Korean peninsula was thrown back to the Cold War. The conduct of joint US-South Korea anti-submarine drills in the East Sea late in July escalated military tensions on the peninsula to new heights.

The Lee government’s attitude toward dissent may have hardened as its version of events failed to convince. One opinion poll Kim cites showed only 32.5 percent of people believing that North Korea had been responsible for the sinking of the Cheonan.

Following discussion of the Cheonan incident, Kim Man-bok makes some policy recommendations. He calls first for the strengthening of South Korean defences against any future asymmetric attack by North Korea in the West Sea and second for significant increase in defence expenditure. He complains that the rate of increase in national defence expenditure under Lee Myung-bak was only around 3.4 percent, whereas the Roh Moo-hyun government had set a goal of an annual increase of 9 percent, and in fact did actually increase it by 8.8 percent.

In thus formulating his recommendations to give priority to stepped-up military measures, Kim is on well-established, conservative ground, writing as one might expect an intelligence chief (even a former one) to write. It was his third point that was controversial:

Third, the government should heed the demand of citizens who desire peace not war. … For this, all channels of South-North communication have to be quickly restored and expanded and the accumulation of problems between the two sides resolved through dialogue. In particular, communication must be restored between the ships and naval commands of South and North, and the system of emergency communications between responsible staff offices of both sides must be restored. If necessary, unofficial delegates should be exchanged, and as a further step in this direction, a third South-North Summit Meeting should be promoted.

In the postscript to his article, written subsequent to the Yeonpyeong incident of 23 November 2010 and published only in the Japanese version, Kim Man-bok makes clear that he regards the context – heightened tensions and breakdown of communications between South and North – as crucial. He writes of South Korea’s “defeat in the battle of Yeonpyeong” and gives some examples of apparent dissension in the ranks of the South Korean government that followed.

Kim’s analysis concludes with his listing, without discussion, the main Korea-related findings of the Wiki-leaks material: that North Korea is likely to try to sell not only nuclear technology but also plutonium; that Kim Jung-il is not likely to live more than three to five years and North Korea would likely collapse a year or two after that; that North Korea’s military provocations against South Korea signaled the last-ditch struggle of a collapsing dictatorship; that the Lee Myung-bak government had resolved to freeze South-North relations for the remainder of its term; that in the event of North Korean collapse South Korea and the United States would move to unify the Korean peninsula; that China’s consent to such process could be won by promising the participation of Chinese enterprises in the development of North Korea’s rich underground resources; and that China would not object to a post-unification “purely benign” alliance between a unified Korea and the US. Kim simply presents these materials without comment. He concludes:

this author becomes even more firmly convinced that the present situation of heightened tension on the Korean peninsula was due to “the Lee government exacerbating relations with the north because it is convinced that North Korea will collapse.” Even in the short period remaining of his term of office, President Lee Myung-bak must make efforts to resume the Six Party conference to achieve a peaceful resolution of the North’s nuclear problem and contribute to the peace and stability of Northeast Asia by implementing existing agreements for the establishment of the “West Sea Special Zone of Peace and Cooperation,” towards the ultimate goal of peaceful unification of the Korean peninsula.

The “Kim Man-bok Affair”

|

Kim Man-bok on the front page of Joongang ilbo, January 10, 2008 |

The article has now become an “affair.” In writing such an essay, there is no doubt that Kim Man-bok was, at least in part, self-serving. In other words, he wrote to justify his actions as Director of the National Intelligence Service and to contrast what he believed to be the success of the Northern policies adopted under the Roh government with the tensions, clashes, and risk of all-out war that have risen since then. Being “self-serving,” however, is inevitable when a participant writes of events in which he played a central role, and it should enhance, rather than diminish, interest in such an account.

Who then is Kim Man-bok? A life-long KCIA agent, he joined the agency in 1974 right after graduating from Seoul National University’s Law school, the elite of elites. He served the agency throughout his career, rising through the ranks to become the director in 2006, a post he held until 2008. In the 1970s when students sharply criticized the dictatorship, Kim was active in monitoring and controlling their activities, a career that became a source of tension with the liberal Kim Dae Jung government a quarter of a century later. But he participated in the preparation for the first inter-Korean summit in 2000 and was promoted as a reward for his work on the South-North protocols. Under the Roh Moo-Hyun administration, he led the 2003 government investigation team that laid the groundwork for dispatching Korean soldiers to Iraq the following year.

Kim’s account is not especially shocking, save in the reminder it provides of how different the Korean peninsula was just over three years ago, when senior officials on both sides negotiated in apparent good faith and brought the rival states to the brink of what would have been an epochal shift. The few sentences from the 2007 Summit that he quotes (first in the Korean book, then in the Japanese journal) are indeed new, but they add no more than a gloss to what is already known of those exchanges.

Kim Man-bok had been the subject of vituperative attacks in South Korea long before the present contretemps. He is accused of having told North Korea, on the eve of the 2007 presidential elections, that South Korea’s Northern policy could be expected to remain more or less unchanged under a Lee Myung-bak government. Though roundly attacked by conservatives in South Korea for this, in truth he had done nothing more than get things wrong, as indeed intelligence organs, much of the time, are wont to do.

He has also been accused, by Chosun ilbo in 2008, of devoting too much attention in the last days of the Roh government to negotiating with North Korea over the size and shape of a stone to commemorate the Summit of that year.6 Whatever be the truth of the story of the monument, unless it is placed in the context of the hugely ambitious schemes for negotiating a different future for the country that were on tables in Seoul and Pyongyang at that time, it seems ineffably trivial.7 The Chosun, which broke the “news” on 13 January that Sekai had run Kim’s article, editorialized the following day that “it is no longer puzzling that the agency did not catch even one [North Korean] spy while Mr. Kim was its director” and “we now must closely reexamine how the agency was run [during his tenure].”

The attack on Kim in the conservative press was immediately followed by Yangjihoe (Sunlit Land Association), a group of retired intelligence officers) that expelled Kim from its membership. What is perhaps most telling is the fact that conservatives have savagely begun to criticize one of the arguably most conservative of the officials of the Kim Dae Jung/Roh Moo-hyun era, with profound implications for the future of Korean democracy.

Sekai editor Okamoto voices the fear that the Lee government is turning against free expression of opinion and reverting to the oppressive ways of past, authoritarian governments. As it happens, the dispute in Seoul coincided with submission of a report by the UN Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Opinion and Expression (Frank La Rue) to the United Nations Human Rights Council, stating that freedom of expression had indeed diminished in South Korea since the coming to power of the Lee Myung-bak government and noting the “increasing number of cases where individuals who do not agree with the government’s position are prosecuted and punished based on domestic laws and regulations that do not conform to international law.”8

Gavan McCormack is a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal and an emeritus professor of Australian National University. His book, Target North Korea: Pushing North Korea to the Brink of Nuclear Catastrophe, was published in English and Japanese in 2004 (Nation Books and Heibonsha) and in Korean (Icarus Media) in 2006. He is the author, most recently, of Client State: Japan in the American Embrace (New York, 2007, Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing 2008). The translated excerpts from Lee Myung-bak’s article are all taken from the version published in Japanese in Sekai, February 2011, and all translations are by the author.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, Contested Waters – Contested Texts: Storm over Korea’s West Sea, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 8 No 5, February 21, 2011.

For articles on related themes see

See Seunghun Lee and J.J. Suh, “Rush to Judgement: Inconsistencies in South Korea’s Cheonan Report,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 12 July 2010.

Tim Beal, “Korean Brinkmanship, American Provocation, and the Road to War: the manufacturing of a crisis,” The Asia-Pacific Journal,” 20 December, 2010.

Wada Haruki, “From the Firing at Yeonpyeong Island to a Comprehensive Solution to the Problems of Division and War in Korea,” 13 December, 2010.

Nan Kim and John McGlynn, “Factsheet: WEST SEA CRISIS IN KOREA,” 6 December, 2010.

Paik Nak-chung, “Reflections on Korea in 2010: Trials and prospects for recovery of common sense in 2011,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, January 10, 2011.

John McGlynn, “Politics in Command: The “International” Investigation into the Sinking of the Cheonan and the Risk of a New Korean War,” June 14, 2010.

Tanaka Sakai, Who Sank the South Korean Warship Cheonan? A New Stage in the US-Korean War and US-China Relations, May 7, 2010.

Notes

1 “Funso no umi, ‘Sohe’ o heiwa to hanei no umi ni suru tame ni,” Sekai, February 2011, pp. 56-66.

2 I here refer to the Japanese version of this article, written by Tokyo correspondent Cha Hak-bon, published on line 13 January as “Moto Kokujoincho ‘Yeonpyeongdo hogeki wa gen seiken ga maneita’,” in 2 parts, Chosun ilbo, link.

3 Chon Gwon-hyon, “Koramu, Iwanami shoten ‘Sekai’ ni kiko shita moto kokkajohoin-cho,” Chosun ilbo, 30 January 2011.

4 Okamoto Atsushi, “Kim Man-bok shi e no Kankoku, kokkajohoin no kokuhatsu e no komento,” 31 January 2011.

5 See Seunghun Lee and J.J. Suh, “Rush to Judgement: Inconsistencies in South Korea’s Cheonan Report,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 12 July 2010.

6 “All this fuss just to leave Roh’s name in North Korea,” Chosun ilbo, 15 February 2008, link.

7 For a detailed account of the complex South-North cooperation schemes as of late 2007, that warrants reading in conjunction with the Kim Man-bok account introduced in the present article, see especially the second part of Aidan Foster-Carter’s two-part article in 38 North, 20 January 2011, “Lee Myung Bak, Pragmatic Moderate? The Way We Were, 2007,” link, and “Scrapping the Second Summit: Lee Myung Bak’s Fateful Mis-step,” link.

8 Son Jun-hyun, “U.N. rapporteur reports freedom of expression severely curtailed under Lee administration,” The Hankyoreh, 18 February 2011.