Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War1

Mark E. Caprio

The breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s prodded open the archival doors of once closed regimes releasing interesting information on Soviet-North Korean-Chinese relations during the Cold War. Documents released from these archives contributed new evidence to enrich our understanding of old questions.2 One such question concerns the origins of the Korean War. Documents from these archives demonstrate an active correspondence between the three communist leaders in Northeast Asia—Josef Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Kim Il Sung—regarding the planning and orchestration of this war fought primarily among the two Korean states, the United States, and China.3 This new evidence has encouraged scholars to reformulate fundamental views of this war, particularly its place in Cold War history.

The timing of the documents’ release—just as the Soviet-as-enemy image faded, and the post-Cold War rogue state-as-enemy image emerged—is intriguing. This new evidence’s apparent support of North Korean culpability in the war’s origins proved useful to those who accused North Korea of once again breaching regional peace by launching nuclear programs and other provocative activities. They strengthened calls for close vigilance lest the communist state launch a second surprise, unprovoked attack against its southern neighbor. The contribution made by these documents, however, is limited to enhanced understanding of relations between members of the northern triangle (the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea); they contribute little to understanding of the southern triangle (the United States, Japan, and South Korea). This critical limitation does not enter into the analyses of many scholars who have used these documents to update understanding of this war’s origins. The purpose of this paper is to address questions that require attention before we can fully understand the causes of the Korean War. These questions demand information on the interactions by members of the southern triangle prior to the outbreak of conventional war.

It is well known that South Korean President Syngman Rhee equaled his North Korean counterpart’s ambitions to use military force to reunite his homeland, and that the United States was determined to prevent his doing so on his own. Were these ambitions aimed at preserving the peace, or preserving control over the war that many perceived as inevitable? If the former, why didn’t the United States (along with the Soviet Union) exert greater efforts to curtail the increasing outbreaks of armed violence that took place between the two Korean states? If the latter, did intelligence gathered by agents in North Korea allow the United States a window to view Kim Il Sung’s intentions? If so, how did it use this information to form a counter strategy? And, did such strategy enter into discussions between Syngman Rhee and high-level U.S. officials?

North Korean War Preparations

The greatest impact that this new evidence has had is in our understanding of the North Korea leadership’s preparation for the war, particularly its efforts to convince Stalin of its necessity and the plans it proposed to initiate the early morning attack on June 25, 1950, the date that the United States and South Korea mark as the start of the Korean War. Much of this new information was contained in telegrams exchanged by the Soviet diplomatic corps in P’yǒngyang and Stalin in Moscow that Russian President Boris Yeltsin presented to South Korean President Kim Young Sam during his state visit to Seoul in June 1994. Contrary to traditional views that charged Stalin with initiating plans for North Korea’s southern attack, the documents portray Kim Il Sung as eager to initiate war with South Korea and Stalin as reluctant to give Kim the green light to attack. The war’s origins are thus rooted in Korean nationalist sentiment rather than as part of a Soviet-led global communist revolution. The documents also suggest that Stalin offered Kim his blessing to attack sometime in late 1949, but cautioned that the Soviet Union would not participate beyond supplying North Korea with weapons. As a precautionary step he urged the North Korean leader to approach Mao for any further assistance he needed. Finally, the telegrams discuss the North Korean military’s strengths and weaknesses, and show concern that the United States, or even Japan, would offer South Korea assistance in fighting the war. Kathryn Weathersby, who is responsible for the lion’s share of the English translations of these telegrams, concludes that the documents support the “argument that the impetus for the war came from P’yongyang, not Moscow.” They do not, by contrast, sustain the option (advanced primarily by Bruce Cumings) that the attack was “a defensive response to provocation by the South.”4 But can we refute this speculation with confidence while so many questions regarding the aims and actions of the United States and South Korea remain unclear?5

|

Mao Zedong Josef Stalin Kim Il Sung |

A key point is just when Josef Stalin gave Kim Il Sung the green light to initiate his war with the South, and what encouraged the Soviet leader to support a campaign concerning which he harbored serious doubts of its success. Weathersby and others write that Kim probably first broached the idea in March 1949, during his month-long visit to Moscow. Wada Haruki notes mention of such a proposal in a report authored by a Russian Foreign Ministry official on Kim’s meeting with Stalin around this time.6 Stalin, on this occasion, advised restraint; he predicted that the South would attack first, thus allowing the North the opportunity to fulfill its ambitions by counterattack.7 Stalin probably anticipated that the planned U.S. withdrawal of its troops from the peninsula would offer South Korean President Syngman Rhee the opportunity to expand his frequent incursions at the thirty-eighth parallel into all-out war. Kim’s patience, however, wore thin when the attack did not materialize. In August 1949, about six weeks after the late June withdrawal of U.S. troops, he presented Soviet Ambassador to North Korea, Terenti Shtykov, a rather modest plan to invade south. The North Korean military would occupy the Ongjin Peninsula before moving eastward across the 38th parallel toward the ancient capital of Kaesǒng. Successful operation of this campaign would reduce the North Korean border along the parallel by 120 kilometers,8 an area where much of the heavy border conflicts between the two Koreas took place.9

|

The division of Korea prior to the Korean War. Inter-Korean battles took place primarily toward the far western point of division. |

At a later date Kim proposed a second, extended, plan to move south into Seoul before eventually making his way down to Korea’s traditional southernmost border. North Korean success in this more ambitious plan was contingent on a number of factors: support from partisan groups embedded in the South; swift completion to ensure that the United States remained out of the war; and Soviet support through the supply of military hardware and training of North Korean forces.

Part of Kim’s ambition to initiate a war with the South no doubt was driven by nationalist sentiment and the political prize to be gained by reuniting the peninsula. Yet, his original plan suggests more, particularly when placed in the context of the heavy fighting that occurred along the thirty-eighth parallel. We cannot overlook the security relief that North Korea would gain by successfully eliminating the North-South divide that cut through the Ongjin peninsula. Developments in late 1949 and early 1950 armed Kim with confidence that he could succeed in a southern attack, and that he would not have to worry about United States or Japanese intervention.10

Soviet officials remained skeptical. On August 27, 1949, Shtykov submitted to his superiors a negative assessment of Kim’s plan: the United States would surely assist South Korea by providing weapons and ammunition; it would surely hurl negative propaganda in the direction of the Soviet Union; and the North Koreans did not hold the decisive military advantage over the South that they needed to succeed.11 These concerns influenced the content of the list of questions that Stalin submitted to the North Korean leadership through his embassy on September 11. He asked Kim to evaluate 1) South Korea’s military strength; 2) the ability of the partisan groups in the South to support the North’s efforts; 3) public opinion in the South regarding an invasion by the North; 4) the possible reaction by the United States military which remained in South Korea; 5) the readiness and attitudes of the North Korean military; and 6) the chances for success of his plan.12

Even if the United States did not respond to a crisis on the Korean peninsula with troop deployment, Soviet leadership believed that it would help South Korea by supplying ample weapons, ammunition, and spare parts, while enlisting help from its allies—most likely the remnants of the war-experienced Japanese—to participate in the fighting, as suggested in a May 1949 warning to Mao Zedong by the Soviet representative to the Chinese Central Party Meeting, I. V. Kovalev.13

Shtykov, in August 1949, also warned that the United States would provide it with weapons and ammunition in case war broke out on the Korean peninsula. In addition, it would deploy Japanese troops to help defend South Korea.14 One month later he telegraphed Moscow saying that the United States, feeling the sting from losing China, would do everything in its power to support Syngman Rhee so as not to “lose Korea” to communism.15 The possibility of foreign troops entering the war following an attack by the North did not seem to faze Kim. When questioned over the possibility of Japanese participation by Mao in May 1950, he responded that while he thought the chances for this development were low, in the event it did occur the North Korean military would fight with even greater ferocity.16

Another key reason for Stalin’s initial hesitancy was the weak state of the North Korean military. Its successful engagement in even a quick war would require Soviet assistance in the form of military hardware. The weapons and munitions that the North Korean military had been using to hold off South Korean incursions along the parallel were far from adequate. Earlier, on February 3, 1949, Ambassador Shtykov informed Moscow of these difficulties:

The situation at the 38th parallel is one of unrest. South Korean police and military battalions infringe on the 38th parallel just about every day. They also attack North Korean patrol sentry posts. There are two brigades of North Korean patrol battalions protecting the 38th parallel. These brigades are armed with just Japanese pistols. As well, these pistols carry but three to ten rounds. They have no automatic weapons. Because North Korean brigades face this situation, when South Korean police battalions attack they cannot counterattack; they can only retreat. They exhaust their ammunition, which sometimes falls into the hands of the South Korean police battalions.17

On April 20, 1949 he provided his superiors with a list of the areas in which the North Korean military was weak: pilots were receiving inadequate training; experienced generals were not being appointed; and the Soviet promises to provide equipment remained unfulfilled.18

From this time, and continuing through June 1950, the Soviet Union began increasing the amount of military hardware that they sent to North Korea. Yet, even after the war was under way the North Korean government complained about inadequate war supplies. On July 3, Shtykov cabled to Moscow a list of military needs that ranged from automatic pistols to trucks.19 The Soviets also promised to enroll a number of Koreans in their pilot training course. Unlike the South, which was the beneficiary of United States gifts of arms, the Soviets required that the North pay for all equipment received.20 This condition the Soviets also levied on the Chinese, as well, by advancing them credits for future years (1951-2) to pay for the equipment that the Soviet Union provided for them to fight the war in 1950.

The Soviet Union also insisted that the North Korean government exhaust all efforts to bring a peaceful solution to the North-South divide prior to initiating war. On June 7, just weeks prior to the outbreak of war, Kim Il Sung advanced a plan that called for both Koreas to resolve their differences through peaceful means. This plan introduced a “Democratic Front for Attainment of Unification of the Fatherland” that called for elections to be held from August 5, and the first session of the “unified supreme legislative organ” to hold its opening session on Liberation Day, August 15. U.S. Ambassador to South Korea, John Muccio, who cabled this news to the U.S. secretary of state, dismissed it as “purely propaganda.”21 Nonetheless, the two sides did meet at the 38th parallel with nothing substantial resulting from this effort.

Sometime in early 1950 Stalin apparently provided Kim with the assurance he needed to advance south.22 On January 19, 1950 Shtykov reported to Moscow that during a recent visit with Kim, the intoxicated North Korean leader had told him that if Stalin would not receive him in Moscow to discuss war plans he would try and arrange a meeting with Mao in Beijing. Within two weeks, on January 30, Stalin informed Kim through his ambassador that he would support his reunification plans, though much work remained in order to minimize risk.23 What Kim perhaps did not know was that Mao was in Moscow at the time. Stalin no doubt used the interval prior to responding to Kim’s threat to discuss with the Chinese leader one way to minimize risk—Chinese military assistance. Chen Jian writes, the Chinese “should not have been surprised by the North Korean invasion, but they certainly were shocked by the quick unyielding American invasion.”24

Stalin invited Kim to Moscow and on March 30 the Korean leader, along with his vice-premier and foreign minister Pak Hǒnyǒng, traveled to the Soviet capital where they remained just shy of one month.

|

North Korean Vice-Premier Pak Hǒnyǒng, 1946 |

The lone document available of the Stalin-Kim discussions, a summary compiled by the Soviet Union Central Committee’s International Department, suggests how changes in the international environment, specifically the Chinese Communist victory in its civil war, allowed Stalin to consider offering Kim support. It also noted Stalin’s concern, primarily the threat of the United States coming to South Korea’s assistance. Stalin speculated that the recently signed Soviet-Chinese treaty of friendship might keep the United States out of the war. He also warned that the North Koreans should not expect “direct Soviet participation in the war.” They must make “thorough preparation” for the war, and draw up a “detailed plan for the offensive.” It was at this time that Stalin also stipulated that Kim make “fresh proposals for peaceful unification.” Their rejection by the South, he reasoned, will open the door for a just “counterattack.” Kim and Pak reportedly reassured the Soviet leader. The summary paraphrased their responses as follows:

Kim Il Sung gave a more detailed analysis of why Americans would not interfere. The attack would be swift and the war would be won within three days; the guerrilla movement in the South has grown stronger and a major uprising can be expected. Americans won’t have time to prepare and by the time they come to their senses, all the Korean people will be enthusiastically supporting the new government.

Pak Hon-yong elaborated on the thesis of a strong guerrilla movement in South Korea. He predicted that 200,000 party members would participate as leaders of the mass uprising.25

One must wonder about the extent to which Stalin bought into Kim’s contention that he could win the war prior to the United States entering the battles. Both parties were aware of Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s January speech that placed the Korean peninsula outside of United States interests.26 They were also, however, aware of the growing influence of McCarthyism, and the senator’s accusations against those who allegedly “lost China.” Could Truman afford to watch this war from the sidelines as well? Stalin revealed his doubts by insisting that Kim and Pak travel to Beijing to gain Mao’s consent to come to North Korea’s assistance should the United States enter the war. Mao could now lend this support as his civil war with the Nationalist Chinese (save for the Taiwan issue) had ended in his favor. He could also return to North Korea the battle tested soldiers, who later served as shock forces in the Korean War, that Kim had sent him for his war. Finally, the Soviet Union’s successful nuclear test provided evidence of a factor that Stalin thought might deter the United States from entering the Korean battlefield after the outbreak of war.27

Available documents depict the Soviet leader as still harboring doubts over North Korea’s chances. If so, why then did he endorse Kim’s plan? Mao’s success in his war, coupled with Kim’s threats in early January, offer room for speculation over the extent to which the North Korean leader’s threat to seek China’s help may have influenced Stalin’s calculations regarding the short-term Korean peninsula issue, as well as the long-term issue of Asian and global communist leadership. The Sino-Soviet rift is generally dated from the late 1950s to early 1960s. But might its seeds have been sown earlier? Might Mao’s victory over the Chinese Nationalists have sent Stalin a message regarding a future competition for Communist bloc leadership?

Can we interpret the Soviet leader’s cold reception toward Mao during his January 1950 visit to Moscow as a strategic ploy to remind Mao (and possibly others) of his senior position?28 Might we see in Kim’s threat to turn to Mao should Stalin refuse to assist him the North Korean leader uncovering an opportunity to play the two communist leaders of each other, as he would successfully do from later in the decade? And did Stalin’s sudden decision to assist Kim reflect his realization that he could “lose” North Korea to China should he continue to deny Kim support?29

|

Mao and Stalin: Communist allies? |

An Asian Campaign?

The archives demonstrate Stalin, Mao, and Kim’s apparent belief that viewed the battles for the Korean peninsula should be fought by Asians, be it the Chinese assisting the North or the Japanese aiding the South. The two superpowers would support, but not directly engage in, the battles. Allen S. Whiting’s China Crosses the Yalu: The Decision to Enter the Korean War, long considered the defining work on China’s participation in this war, provides inconclusive evidence regarding China’s role in the war’s planning, a task Whiting argued was performed by the Soviet Union. At the time, China was more preoccupied with Tibet and Taiwan than the Korean peninsula. Its primary interest in the war lay in the ramifications of a North Korean victory that would, Mao claimed, keep a resurgent Japan from returning to the Asian continent and weaken United States influence in the region.30

Chen Jian’s China’s Road to the Korean War, published over three decades later, exploits new archival material to argue that China’s role in the war’s planning may have been more critical than previously believed. The turning point came after Mao’s October 1949 victory over the Nationalists, which allowed the Chinese leader greater flexibility in assisting his communist ally. As suggested above, Kim Il Sung may also have exploited this turn of events in dealing with the Soviets from January 1950. Stalin encouraged Mao, perhaps during his visit to Moscow, to support North Korean efforts to liberate the South by providing soldiers to fight on the peninsula. Stalin did not want to engage Soviet forces directly in the battles primarily because of the harm such participation would have on the global image of the Soviet Union. Even if Soviet assistance might help the North Korean military carry the day, it would cost them more in their ideological war with the United States.31 Stalin further claimed that the Soviet Union was bound by an agreement that it had signed with the United States to honor the 38th parallel; he did not want to face accusations of having broken this agreement. The Chinese, too, let Stalin off the hook by agreeing that this battle was not one for the Soviets: Stalin could best support the North Korean cause by providing military advice and hardware without having to worry as much about United States propaganda after the fighting commenced.32

|

Mao (right) and Zhou Enlai flank Kim in Beijing |

The Chinese, however, were free of such constraints and thus could join in the fighting if necessary.33 Mao believed the likelihood of U.S. participation was slim as, he reasoned, the United States would not risk triggering World War III by coming to the South’s assistance.34 His confidence was further bolstered by the Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance that the two communist giants signed on January 20, the day that Stalin received notice of Kim’s threat to seek Mao’s assistance. The agreements allowed China to purchase a large cache of military hardware with the $300 million loan that the Soviet Union provided.35

From the beginning it was understood that the Chinese would only join the battle if the United States intervened. Otherwise, the war was to remain a “Korean war.” Stalin explained this to Kim Il Sung during the North Korean leader’s visit to Moscow in March 1950. Kim reportedly retorted that China’s assistance would be unnecessary as the war would be over within three days.36 Mao repeated his promise to provide military assistance during Kim and Pak Hǒnyǒng’s visit to Beijing in May 1950. He further inquired as to whether it was necessary for Chinese troops to amass at the Korean border just in case, an offer that Kim politely declined as not necessary.37

|

Chinese troops cross the Yalu River into Korea |

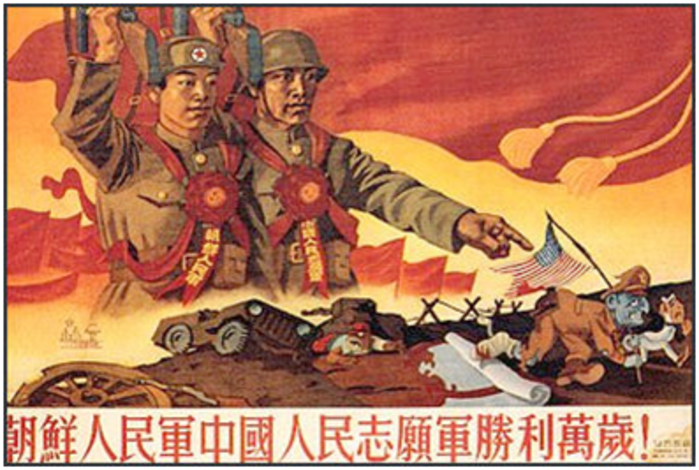

The timing of the Chinese entrance into the war suggests their motivations to be as much about state security as they were to assist their Korean ally. They did not cross into North Korean territory until October 19, 1950, a full three months after the United States joined the battle in early July 1950. This was close to two months after the United States first bombed Chinese territory on August 27,38 and almost two weeks after the United States crossed the 38th parallel on October 7. Three weeks later, on October 27, they engaged American troops, but then disappeared for nearly a month. Bruce Cumings suggests that this strategy was designed to “stop the American march to the Yalu.”39 The UN and South Korean militaries continued to advance. (Cumings’ most recent book caries a picture of U.S. troops enjoying Thanksgiving dinner on the banks of the Yalu River.) On November 27, Chinese troops finally began the assault that forced enemy forces to retreat. Thus, in spite of the subsequent Chinese and North Korean rhetoric of the close teeth-lips relations that the two peoples have forged over their long histories, it appears that the Chinese entered the fighting only after it became apparent that their communist ally was losing and that the United States might act on it pledge to rollback communism beyond North Korean territory, and threaten their sovereignty as well.

|

“Long live the Victory of the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese Volunteer Army!” |

The Chinese and Soviets both considered the possibility that the United States would enlist assistance from its Asian partner, Japan, if it became necessary to assist South Korea in the war. While attending the Chinese Central Party Meeting in May 1949, Soviet representative I. V. Kovalev transmitted to Moscow the following message from Mao Zedong:

Our Korean comrades think that the United States will soon withdraw its troops from the Korean peninsula. However, what concerns our Korean comrades is that Japanese troops will be intermixed among the United States troops and the South will attack the North…. We feel that whether or not Japanese troops are intermixed with South Korean troops is something that has to be considered. And if they do in fact join then caution must be shown…. Even if the US military does retreat, and the Japanese do not cross over, the North should not hasten to advance south, but wait until the conditions are more appropriate. For if it does advance south MacArthur would surely send Japanese military forces and Japanese weapons to Korea.40

Why might the Chinese and Soviets anticipate the United States, in clear violation of the letter and spirit of Allied wartime and postwar agreements, enlist Japanese participation in a war on the Korean peninsula? Despite their defeat, Japan had experienced soldiers who could conceal their identity should they be incorporated into South Korean battalions.41 Both communist and nationalist Chinese had made use of Japanese military skills in their civil war.42 Mao and Stalin no doubt were also privy to U.S. efforts to remilitarize Japan following the 1948 “reverse course” in its occupation policy. South Korean President Syngman Rhee’s trip to Tokyo in 1948 may also have signaled to North Korea’s communist allies attempts by the United States to coordinate its policies with South Korea and Japan. Rumors had been circulating through southern Korea from early into its post-liberation military occupation that the United States was “building Japan as a military power.” During the 1948 Cheju Island rebellion some believed that Japanese were actually “participating in the restoration of peace.”43

Following the start of the war the Soviet government, apparently convinced that the United States had employed Japanese to fight, directed Andrei Vyshinsky at the United Nations in New York to “support the protest of the government of [North Korea] against the use by the Americans of Japanese servicemen in the war in Korea.” It further informed the Soviet Ambassador to the United States in Washington that

Japanese servicemen participated in battles in the area of Seoul together with American troops, that one Japanese company participated in battles in the area of Chkholvon (In’chǒn) and that a significant number of Japanese are found in the 7th and 8th divisions of the Rhee Syngman troops.

This constituted “a gross violation of the Potsdam declaration, and also of section III of the resolution of the Far Eastern Commission Basic Policy in relation to Japan after Capitulation of June 19, 1947, and the resolution adopted on the basis of this document on Prohibition of Military Activity in Japan and Use of Japanese Military Equipment of February 12, 1948.”44

The social and economic effects of the Korean War on Japan are well recorded.45 Much less researched is Japan’s military cooperation, which hedged on violation of international agreements stipulating Japan’s demilitarization and of Japan’s postwar constitution that had just recently been promulgated. Ōnuma Hisao’s edited volume provides the best summary of Japan’s participation in this war. In terms of military-related activities, it is well know that Japan contributed 25 minesweepers to clear In’chǒn Harbor just ahead of Douglas MacArthur’s invasion forces in September 1950, as well as another 21 such vessels to clear other North Korean ports.46 Less known are the 21 Japanese who perished during these operations. Dozens of other war-deaths were reported among Japanese who provided logistical support, including civilians who were dispatched with Japan-based American units to work as translators and laborers. Whether Japanese actually engaged in combat remains unclear. In November 1950, Japan’s Mainichi shinbun reported that the North Koreans were holding one Japanese prisoner but it is not certain whether this person was a soldier or civilian. Ōnuma suggests that North Korean claims of Japanese in combat might have come from their mistaking U.S. Nisei soldiers for “Japanese” soldiers.47 There is also the possibility that Japan-based Korean volunteers who were intermixed in American combat units may have been mistaken for Japanese nationals.48 Japanese citizens did volunteer to fight in the war, but it is unclear whether they were actually accepted. Ōnuma concludes that, although not impossible, to date documentation has not surfaced which demonstrates that Japanese served in a military capacity during the Korean War.49

The South Korea-United States-Japan Triangle

In 1997 the prominent Cold War historian, John Lewis Gaddis, concluded that the evidence from Soviet and Chinese sources “pin down a chain of causation for the Korean War that requires neither speculation about ‘hidden’ histories nor the insistence that there can never be unintended consequences.” No convincing evidence exists, he held, to support an argument that “North Koreans, the Soviets, and the Chinese [were] somehow ‘maneuvered’ into attacking South Korea,” or that either Truman administration officials or General MacArthur were colluding with [Syngman] Rhee to get him to attack North Korea.”50 Gaddis, along with others who have used the evidence gleaned from Russian and Chinese archives to confirm North Korean’s unqualified guilt in starting the Korean War and combat “revisionist” histories of the war, may indeed be correct in drawing this conclusion. On the other hand, the lack of records does not necessarily absolve the U.S. and South Korea from playing any role in the outbreak of war. Lack of sufficient information on a number of important discussions held among officials leave a number of unanswered questions critical to understanding the Korean War’s origins.51

|

Douglas MacArthur with Syngman Rhee Douglas MacArthur with Yoshida Shigeru |

Most important, this research often fails to mention, much less critically examine, Syngman Rhee’s aspirations. Nor does it consider the possible effect that South Korea’s belligerent actions along the 38th parallel may have had on North Korean actions. Documents demonstrating Rhee’s interest in engaging the North in war predate the earliest record of Kim’s military ambitions by at least one month. On February 8, 1949, the South Korean president met with Ambassador John Muccio and Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall in Seoul. Here the Korean president listed the following as justifications for initiating a war with the North: the South Korean military could easily be increased by 100,000 if it drew from the 150,000 to 200,000 Koreans who had recently fought with the Japanese or the Nationalist Chinese.52

Moreover, the morale of the South Korean military was greater than that of the North Koreans. If war broke out he expected mass defections from the enemy. Finally, the United Nations’ recognition of South Korea legitimized its rule over the entire peninsula (as stipulated in its constitution). Thus, he concluded, there was “nothing [to be] gained by waiting.” Muccio replied by advising, as Stalin would Kim, that Rhee first explore peaceful options. The ambassador also warned that “no invasion of North Korea could in any event take place while the United States had combat troops in Korea.”53 With U.S. combat troops initially scheduled to leave the peninsula in May (this departure was later pushed back to the end of June), did Muccio’s reply leave room for the possibility of a South Korean invasion after the United States military withdrew as Stalin predicted during his discussions with Kim the following month? Perhaps. Around this time North Korea began to lay mines along its side of the 38th parallel.54

The United States Commitment to South Korea

|

Ambassador Muccio (right) meeting with President Rhee |

Key to Rhee’s military policies—be they offensive or defensive—was the United States’ commitment to the Korean peninsula after it withdrew its troops. Would it return these troops should the peninsula erupt in war? Publicly U.S. government officials, most notably Secretary of State Dean Acheson, issued statements that placed Korea outside of their country’s defense perimeter in Asia.

The South Korean president voiced his concern over the U.S. commitment in May 1949, during a discussion with Muccio, noting that the Korean people never thought that the United States would abandon China. Yet they did. Rhee then offered the ambassador a history lesson on U.S.-Korean relations, informing him that in the past 45 years the United States had twice “abandoned Korea.”

Theodore Roosevelt had done so the first time and Franklin D. Roosevelt had done so the second time at Yalta. These matters…are in the minds of the Korean people. The Americans liberated Korea, and they give us aid, but if the United States has to be involved in war to save Korea, how much can Korea count on the United States?55

The U.S. ambassador apparently also harbored concern. In the aftermath of the Acheson speech, that was followed by other public statements by Americans of influence that placed the Korean peninsula outside of U.S. national interests, Muccio requested that “those persons particularly charged with drafting speeches and statements…have this problem brought to their attention, so that… Korea may always be included.56 Privately, officials reassured Rhee that the U.S. would not let his country fall to communism. MacArthur, for example, informed the president at his inauguration that the United States would defend his country as if it were California. Rhee, however, wanted more tangible assurance. To ensure U.S. assistance, he pushed the United States (unsuccessfully) to negotiate a defense pact that provided him with offensive weapons, before finally settling for a Mutual-Defense Assistance Act, which the two states signed in July 1949. Upon withdrawal the U.S. military left South Korea $110 million in military equipment and supplies useful to defend the country should it face attack from the north.57

But Rhee wanted offensive weapons, primarily fighter jets and tanks. He used his American contacts to gain U.S. support for his ambition to unify the peninsula by force. A September 30, 1949 letter posted to his biographer and trusted adviser, Dr. Robert Oliver, with instructions to forward its contents to President Truman, argued that the time was ripe for a northern campaign. Quoting Winston Churchill, Rhee implored the U.S. to “give us the tools and we’ll take care of the rest.” He warned the United States not to make Koreans sit tight with our “arms folded.” If the goal is to “bury communism once and for all,” then there is no better time than the present.”58 His later signals, as Philip C. Jessup reported after the ambassador-at-large’s mid-January 1950 meeting with Rhee, sent mixed messages regarding the South Korean president’s military aspirations vis-à-vis the North:

[Rhee’s] primary emphasis was upon the communist menace in Korea and the world. So far as the Korean situation is concerned… they are fighting the guerrilla bands throughout South Korea as well as meeting border forays along the 38th Parallel, Several times he made the statement that they were prepared to fight to the death. With obvious reference to his pleas for further military aid and probably in defense of his domestic security measures, he kept stressing the fact that the infiltrating communists were killing large numbers of people in the area all of the time…. In one of his first talks he explained that they would have a much better strategic defense line if their forces moved into North Korea and he expressed confidence that they could defeat northern opposition. Subsequently, he was careful to add that they were not planning to embark on any conquest. The general tone of his statements, however, lends credence to the belief that he has not objected when the Southern Korean forces along the 38th Parallel have from time to time taken the initiative.59

The United States may have wished to keep President Rhee guessing as to the extent it would come to South Korean assistance. A plan completed by the Department of the Army just after the U.S. military withdrew from the peninsula, however, suggested the decision to intervene on South Korea’s behalf already made. Though rejected by the Joint Chief of Staffs, the scenario it presented outlined the chain of events that the United States would eventually set in motion one year later. After the evacuation of U.S. nationals from the peninsula, the U.S. would introduce the problem to the United Nations Security Council as a “threat to the general peace.” It would then receive UN sanction to form a military task force comprised of a consortium of UN members to be led by the United States to restore “law and order and restoration of the 38th parallel boundary inviolability.” Following the successful completion of these steps, the United States would establish a joint force in South Korea “in view of the emergency situation.” Finally it would apply the Truman Doctrine to Korea, which would allow the U.S. to offer assistance to South Koreans as they “of their own volition actively oppose Communist encroachment and are threatened by [its] tyranny.”60 This plan’s creation, the report continued, was stimulated based on information regarding the Soviet-North Korean agreement of March 17, 1949 that committed the Soviet Union to provide North Korea with “necessary arms and equipment to equip eight battalions of ‘mobile’ border constabulary.” This agreement also committed the Soviets to provide aircraft for the North Korean air force once sufficient personnel had been trained.61

Like Moscow, Washington also advised that South Korea gain the upper hand in the propaganda war by encouraging peaceful unification by offering to negotiate directly with the North Korean regime. The authors of the contingency plan included one such encouragement in their report. For South Koreans a peace proposal would, in addition to forestalling “military aggression by North Korea,” serve as a “psychological weapon placing national interests, independence, and sovereignty above alleged big power politics, and would lend credence to their true nationalist aspirations.” It would also “represent an effort to settle differences by pacific means.” North Korea’s anticipated refusal to cooperate (noted as an advantage) “would further illustrate North Korean intransigence and subservience to the USSR.” A North Korean acceptance (listed as a disadvantage) would “introduce Communist elements into the Korean government and might lead eventually to its subversion by political means.”

This latter concern underlined one point emphasized by the United States since the beginning of its occupation of the southern half of the peninsula: any attempt to implement a true democracy in Korea would force the United States to choose between accepting a coalition (with the very real possibility of a northern majority government), or finding a way to discredit the results. Neither alternative was attractive to a state that had promised to deliver democracy to the recently liberated territory.62 A third option, establishing a separate political administration in the South, proved to be the more practical alternative even though this decision solidified the North-South division.63 The victory by South Korea’s conservative forces, headed by Syngman Rhee, benefited from a left-wing election boycott and apparent election-day fraud.64 In the end, the election succeeded in excluding radical elements from participating in the “Korean state” government, a development that would have been, according to the above outlined “Memorandum,” “very harmful to U.S. interests.”65 Its support for elections limited to southern Korea, and its virtually eliminating the powerful leftist force from these elections, raised the potential for war.

U.S. Intelligence: Clues to the War’s Origins?

The U.S. Department of Army plan demonstrates a keen awareness of the possibility of war on the Korean peninsula. Rather than work to pacify the aggression that plagued the peninsula, it prepared to enter the fray. This begs a third question concerning the extent to which U.S. intelligence was able to monitor North Korean actions and ambitions. How might information regarding North Korean intentions have influenced U.S. strategy by, for example, cautioning Rhee to (as Stalin once cautioned Kim) wait for the other Korea to initiate the battles? Matthew M. Aid, in a study that examined U.S. information gathering in Korea prior to the outbreak of war, describes the efforts as a total failure. This intelligence, he contends, was “able to build up a comprehensive and detailed picture of North Korean military organization and capacities. Reams of intelligence data made its way to Seoul from [South Korean] agents and guerilla teams operating in North Korea.” However, “Tokyo and Washington placed little credence in what the Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) and the American military attaches in Seoul were passing on.”66 He notes the “prolific” amount of information accumulated by the Korean Liaison Offices (KLO), which had sixteen operatives reporting from North Korea (as opposed to four by the CIA).

Between 1 June 1949 and 25 June 1950, KLO filed a total of 1,195 reports, 417 of which were submitted in the six months immediately preceding the North Korean invasion. According to [General Charles A.] Willoughby, these reports covered all aspects of the North Korean military, including preparations for the invasion of the South, the formation of new combat units, military movements, military training and preparedness, the development of the North Korean air force, as well as Soviet and Chinese military assistance to the North Korean People’s Army.67

We are still left in the dark as to why the U.S. apparently did not exploit this information to better prepare itself for a war whose arrival was hardly as “sudden” as U.S. officials describe it. Was the U.S. “failure” to act on this intelligence truly a result of problems of communication or outright incompetence, or was it a planned “failure” consistent with a calculated strategy?

Much of this information is found in the biweekly Intelligence Summary North Korea put out by the United States Armed Forces in Korea (USAFIK). In addition, from early 1948 these reports began a section titled “signs of war” that reported rumors of imminent all-out attack by the North. These rumors intensified as U.S. forces prepared to withdraw from the peninsula. One such “rumor,” that came from the wife of the director of a Soviet hospital in Wǒnsan in January 1950, accurately informed that the attack would come in June 1950.68 However, this prediction was but one of many that, coupled with warnings issued by Syngman Rhee to enlist U.S. military support, no doubt came to be written off by the American government as “wolf calls.” But the reality was that, as documented in G-2 Periodic Reports, just about every week prior to what Secretary of State Dean Acheson anticipated to be a “weekend of comparative rest”69 witnessed some kind of military confrontation by forces situated along the 38th parallel.70

Acheson does not offer reasons as to why the weekend of June 24-25 would have been any different from other weekends that witnessed fighting along the 38th parallel. He also makes no mention of what was behind the efforts of a State Department consultant, John Foster Dulles, who travelled to Seoul less than a week before the war’s outbreak to advise the South Korean National Assembly that they “were not alone.”

|

John Foster Dulles at the 38th parallel in June 1950 |

We also do not know what Dulles and Rhee discussed during this visit, as documentation for yet another secret meeting between the president and a key U.S. official remains unavailable.71 We learn through Russian sources that South Korea began to assemble military forces in greater numbers at this very time, a move that (as Terenti Shtykov reveals) a frantic Kim Il Sung interpreted as the South having learned of his invasion plans. The North Korean leader informs Stalin through his ambassador that he wishes to extend the attack across the entire 38th parallel.

The Southerners have learned the details of the forthcoming advance of the [Korean People’s Army]. As a result, they are taking measures to strengthen the combat of their troops. Defense lines are reinforced and additional units are concentrated in the Ongjin direction…. Instead of a local operation at Ongjin peninsula as a prelude to a general offensive, Kim Il Sung suggests an overall attack on 25 June along the whole front line.

Stalin promptly responded positively to this change of plans.72

Assuming this information to be accurate, but acknowledging the possibility of Kim fabricating a threat to justify extending the attack, raises the question of how and when South Korea (and the United States) learned of North Korea’s plans. The United States secured information on North Korea from a wide variety of sources. The reports often provided general information on the kinds of people who provided this intelligence. The informants included North Korean and Soviet deserters, anti-Japanese guerrillas, Japanese laborers, and a former interpreter for the North Korean People’s committee. Occasionally they offered names and information on how the informants gathered information. Former battery commander Kim Kwan Suk, for example, traveled throughout Hwanghae Province before crossing into South Korea to provide information gleaned from his observations and from former classmates in artillery units.73

Having information on the North’s plans would have placed the United States in a better position to control Rhee’s desires to initiate a northern campaign simply by cautioning him to wait until the enemy made its move.74 As was the case with the Soviet Union, the United States also wanted to avoid being seen as party to the Korean force that initiated a war on the peninsula; thus it refused Rhee the weapons he desired and warned him against attacking north. Unlike the Soviet Union, however, the United States did not have to concern itself with South Korea jumping to a rival superpower should it refuse to assent to its attack plans. If war came South Korea would be dependent on the United States not only for assistance and strategy, but also for the offensive weapons that the U.S. rather than South Korea would control. To the U.S. credit it did not provide Rhee with these weapons. However, without further information we cannot determine whether its intentions were to maintain a prayer for peace, or to maintain control over the weapons (and thus the war) after this peace was broken. The Soviet Union, to the contrary, informed Kim quite early that it would provide North Korea with weapons, but would not fight his battles, regardless of who initiated the war. The North Korean leader thus had nothing to gain by waiting, and everything to lose should (as he expected) the South attack first. The telegrams from the Russian archives provide clues as to North Korea’s intentions, particularly as Kim discussed with Stalin in Moscow. Was the United States privy to the content of these intentions? Might they have entered into the discussions between Rhee and U.S. officials? A fuller, more comprehensive, understanding of the origins of the Korean War is prevented by our inability to answer these questions.

Dr. Rhee Goes to Tokyo. But Why?

One such discussion might possibly have taken place on February 16-17, 1950, right after Stalin informed his ambassador in P’yǒngyang to tell Kim that he would help him, and just one month before Kim traveled to Moscow to confer with Stalin. On these days Syngman Rhee made his second visit to Tokyo as president, the first coming in October 1948 when he paid MacArthur a courtesy call in return for the general’s attendance at his inauguration the previous August. Rhee would make a third visit in January 1953, after MacArthur had been recalled to the United States. The South Korean president and MacArthur spent much time together during these two visits. They drove in together from the airport, and Rhee was MacArthur’s guest at U.S. occupation headquarters during his stay. Rhee’s facility in English eliminated the need for interpretation, and thus one potential resource for information on the content of their discussions. No doubt the two men (perhaps when joined by Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru) discussed Japan-Korea relations. Given the circumstances on the Korean peninsula at the time of their meetings we might also suspect that they exchanged ideas on the very real possibility of all out war on the Korean peninsula.

|

Rhee and MacArthur meet at Haneda Airport (Lafayette College Libraries) |

Rhee verified to his host country’s media that the former, but not the latter, topic was indeed discussed. The Japan Times quoted the president as follows:

No special problem, either economic or military, is connected with my present visit. However, one of the questions in my mind is whether there is any possibility of improving the relations between Korea and Japan. I shall be glad to discuss this with Gen. MacArthur as well as some high officials of the Japanese government.75

Statements that the president made upon returning to Seoul suggest that military issues indeed entered into his discussions with U.S. officials. The Stars and Stripes quoted him as promising “to recover North Korea even though ‘some of our friends across the sea tell us that we must not cherish thoughts of attacking the foreign puppet who stifles the liberties of our people in the north.”76 His more private correspondence with Robert Oliver reveals Rhee’s broaching the weapons issue as well. The theme of Rhee’s three-page letter to Oliver was South Korea’s “military problem.” Here he outlined the defensive reasons for South Korea needing a more advanced air force and navy, and petitioned the United States State Department to revise its “present interpretation of the American perimeter so that it includes Korea.”:

When I was in Tokyo I made the statement that Russia is supplying the Northern forces and that Russia is pressing them to invade the South as soon as “the dust settles in China”. You know that there was nothing new in that statement because the Soviets have continually supplied the North. However, at the present moment the Soviets do not wish to be accused of this complicity, and this is exactly why I made the statement. As a result, the order has been given from Moscow to withdraw all Soviet forces from the North during the next two months.77

This letter demonstrates Rhee’s knowledge of North Korean-Soviet interactions and, possibly, the Stalin-Kim discussions, although Rhee noted that at this point Moscow had yet to give “North Koreans the ‘green light’ to invade the South.” He argued that Moscow had equipped its Korean partner far better than the United States had equipped his army, thus limiting the South Korean military’s ability to withstand a probable North Korean advance.78 From media reportage and Rhee’s correspondence we can guess that the president’s discussions in Tokyo centered most prominently on the growing tension between the two Koreas. They further suggest that his attempt to gain the military equipment and blessing he needed to advance north to have been rebuked.79 But for what reasons? While the few documents available on Kim’s meeting with Stalin offer summaries of both leaders’ thoughts, we are left totally in the dark as to how MacArthur addressed Rhee’s military requests. Did Stalin’s decision to assist Kim enter their conversations? And if so, did the two men discuss strategy to counter this potential? Did MacArthur repeat his promise to defend South Korea, as he would California, if (when?) the North did indeed attack? More definitive answers for such questions regarding these prewar meetings are required before we can close the book on our understanding of the Korean War. Indeed, they constitute core unanswered questions regarding the origins of this war.

Examination of the documents released from the Russian archives since 1994 instruct us on the ambitions harbored by North Korean premier Kim Il Sung to unify the Korean peninsula by war. Those who deem this evidence sufficient to find the North Korean government alone responsible for initiating the battles that left millions dead may indeed prove to be correct. I have argued here that unanswered questions prevent us from drawing this conclusion. First, the telegrams that have drawn so much attention offer little in the way of the context in which they were sent. Were his ambitions to attack the South, for example, motivated simply by the goal of reunifying the peninsula? Eliminating a security hazard? Or both? Second, they also tell us very little about developments in South Korea. We know that Syngman Rhee equally had ambitions to unify the peninsula by force. What did he hope to gain by conducting limited attacks (as opposed to initiating an all out attack) to the north? How did these attacks enter into Rhee’s discussions with U.S. officials?

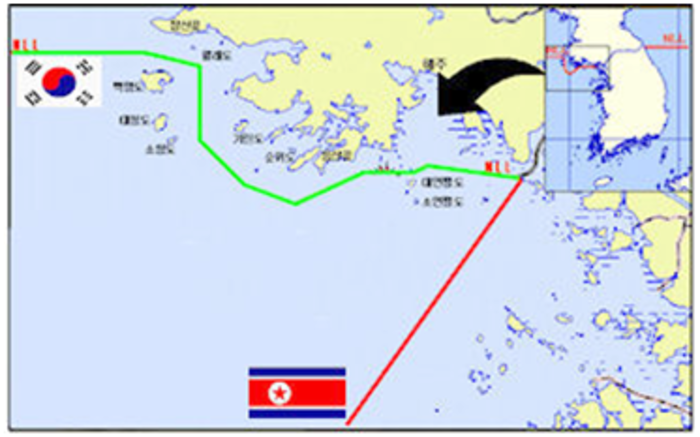

Sixty years later fighting and death returned to the vicinity of the Ongjin peninsula, the region where most of the border insurrections occurred prior to the outbreak of conventional war in June 1950. This aggression reminds us that the Korean War has yet to pass into history. It has survived the past six decades as a limited war quite capable of provoking tension, occasional violent and deadly altercations, and erupting again into a major war. Treatment of the most recent examples, the sinking of the Chǒnan corvette and the shelling of Yǒnpyǒng Island, have rejuvenated Cold War geopolitical divisions as members of the northern triangle question interpretations by the southern triangle on North Korean culpability. The geographic context of both incidents is their location in highly contested waters around islands that are above the South-North division line. It is the waterway leading to these islands in the West Sea—determined by the Northern Limit Line (NLL) drawn by the United States without North Korean input, rather than the islands themselves, that the North Koreans contest.

|

The NLL (depicted in green) and the DMZ (map in insert) |

The political context is a state ostracized by much of the international community, partly by its own doing but more so by its adversarial relations with the United States. These conflictual relations contribute to the economic context that prevents North Korea from participating in the economic institutions that could (as South Korea experienced) lift it from desperate poverty. Like the origins of the Korean War, answers to questions regarding origins and (here) prevention of future altercations are products of a multi-dimensional context that extends beyond views of North Korea as sole culprit, that considers the present from its historical context of post-liberation division, war, and oppression. The short-term tragedy of the Korean War, found in the millions of victims it claimed, is dwarfed by the long-term tragedy wrought by the United States and the Soviet Union’s failure to accept responsibility for their role in dividing the Korean peninsula over the five years that preceded this war, and the six decades that have transpired since its eruption.

Mark E. Caprio is a professor of Korean history at Rikkyo University in Tokyo and a Japan Focus associate. He is the author of Japanese Assimilation Policy in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945. He can be reached at [email protected]. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Mark E. Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 5 No 3, January 31, 2011.

|

This article is part of a series commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the Korean War. Other articles on the sixtieth anniversary of the US-Korean War outbreak are: • Steven Lee, The United States, the United Nations, and the Second Occupation of Korea, 1950-1951. • Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas. • Han Kyung-koo, Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On.

Additional articles on the US-Korean War include: • Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism. • Kim Dong-choon, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War • Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War. • Sheila • Tim Beal, Korean • Wada Haruki, From • Nan Kim |

Notes

1 The quality of an earlier version of this paper was enhanced by generous comments provided by Mark Selden, and from questions and discussion following my presentation of this material at a seminar sponsored by the Institute of Asian Research at the University of British Columbia in February 2005. Its revision has benefited from painfully critical, but thought provoking, observations provided by two anonymous readers from an earlier submission for publication.

2 In addition to research that exploits documents related to the origins of the Korean War (the topic of this paper), Soviet archives have also encouraged studies on Kim Il Sung’s post-Korean War consolidation of power, including Andrei Lankov, Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2005) and Balázs Szalontai, Kim Il Sung in the Khrushchev Era: Soviet-DPRK Relations and the Roots of North Korean Despotism, 1953-1964 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005). In addition, Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, Khrushchev’s Cold War: The Inside Story of an American Adversary (New York: W. W Norton, 2006), is of peripheral interest to this history.

3 The most important studies that consider these documents include Sergei N. Goncharov, John W. Lewis, and Xue Litai, Uncertain Partners: Stalin, Mao, and the Korean War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993); Jian Chen, China’s Road to the Korean War: The Making of the Sino-American Confrontation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994); William Stueck, The Korean War: An International History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995); William Stueck, Rethinking the Korean War: A New Diplomatic and Strategic History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002); Kathryn Weathersby, Soviet Aims in Korea and the Origins of the Korean War, 1945-1950: New Evidence from the Russian Archives (Washington, D. C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 1993); Kathryn Weathersby, “‘Should We Fear This?’: Stalin and the Danger of War With America,” Working Paper #39, Cold War International History Project (July 2002); Kathryn Weathersby, “The Soviet Role in the Korean War: The State of Historical Knowledge,” in The Korean War in World History, edited by William Stueck (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2004); A. V. Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu (Truth and riddles of the Korean war), trans. Shimatomai Nobuo and Kim Sǒngho (Tokyo: Soshinsha 2001); and Wada Haruki, Chōsen sensō zenshi (The complete history of the Korean War) (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2002); Pak Myǒngrim, Hanguk chǒnjaeng ǔi palpar kwa kiwon (The Outbreak and Origins of the Korean War), 2. vols. (Seoul: Nanam, 2003); So Chinchǒl, Hanguk chǒnjaeng ǔi kiwon: “Kukje kongsanchuǔi” ǔi ǔmmo (The Origins of the Korean War: A Plot Conspiracy of “International Communism”) (Seoul: Wongwan Taehakkyo, 1997).

4 Kathryn Weathersby, “New Findings on the Korean War,” CWIHP Bulletin #3 (Fall 1993) 1, 14-18.

5 Indeed, most scholarly works on the Korean War’s origins stop short of answering the question of which Korea fired the first shot in the war. Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War: The Roaring of the Cataract, 1947-1950 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 766; John Merrill, The Peninsular Origins of the Korean War (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1989), 13; Stueck, The Korean War, 10.

6 Kathryn Weathersby, “To Attack, or Not to Attack? Stalin, Kim Il Sung, and the Prelude to War,” CWIHP Bulletin #5 (Spring 1995) 1, 2-9; Wada Haruki, Chōsen sensō zenshi, 82, fn 36.

7 Weathersby, “Should we Fear This?,” 4.

8 Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 61. Kim Il Sung met with the Russian Ambassador on August 12 and 14. A message sent by Shtykov to Moscow began by acknowledging that the peaceful unification option is clearly dead due to Seoul’s unwillingness to accept its terms. Thus, he continued, there is no other option than to unify the peninsula by force.

9 Bruce Cumings (Origins of the Korean War, 388-98) details the border fighting.

10 These developments include the Soviet Union’s successful test of an atomic weapon, the Communist Chinese victory over the Nationalist Chinese army, and finally a positive response from the Soviet Union and China regarding its plan.

11 Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 61.

12 Ibid. 63-64. See also Weathersby, “To Attack, or Not to Attack?” Kim responded to Stalin’s concerns on September 12-13 in a meeting with G. I. Tonkin, the Soviet diplomatic representative to P’yongyang.

13 Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 104-105.

14 Ibid., 61. The Soviet ambassador offered this warning on August 27.

15 Ibid., 69.

16 Ibid., 112.

17 Ibid., 30.

18 Ibid., 36.

19 Ibid., 124.

20 Wada, Chōsen sensō zenshi, 98; Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 446.

21 Ambassador Muccio to the Secretary of State, June 9, 1950 in Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS)VII (Korea) (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), 98-99. North Korea’s track record for peace initiatives was not good. One effort in April 1948 that was attended by two southern conservative leaders, Kim Ku and Kim Kyusik, was able to agree on a platform for peaceful unification. However, it cut off southern power soon after the two Kims returned and thus raised doubt over the North’s sincerity. The failure of this last minute effort to prevent southern Korean elections smoothed the path for Syngman Rhee’s rise to power. See Merrill, The Peninsular Origins of the Korean War, 75-77.

22 Weathersby writes that Stalin initially accepted Kim’s limited offensive to capture the Ongjin peninsula, but later changed his mind after realizing the impossibility that this incursion would remain limited. North Korean actions would surely initiate fighting across the peninsula. Weathersby “Should We Fear This?,” 7.

23 Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 88-89, 92.

24 Chen, China’s Road to the Korean War, 126.

25 Weathersby “Should We Fear This?,” 10. Pak Hǒnyǒng, a leader of the southern Korean Workers’ Party who had fled north in October 1946 on the heels of General John R. Hodge’s suppression of the party, paid with his life in the postwar purges of 1955 that allowed Kim Il Sung to strengthen his totalitarian rule. Kim blamed him for the war’s ultimate failure when southern partisans did not rally following the North’s push south.

26 For discussion of Dean Acheson’s speech see Cumings, Origins of the Korean War, chapter 13. Weathersby notes that the British spy, Donald McLean, had convinced the Soviets that the time was ripe for a northern attack on South Korea. Weathersby “Should We Fear This?,” 11.

27 Bruce Cumings, The Korean War: A History (New York: The Modern Library, 2010), 111.

28 For an interesting account of the initial Stalin-Mao meeting in January 1950 see Goncharov, Lewis, and Xue, Uncertain Partners, chapter 3.

29 Chin O. Chung provides a history of this triangular relationship from the 1960s in his P’yongyang Between Peking and Moscow (University: University of Alabama Press, 1978). Robert P. Simmons considers the pre-Korean War strains that characterized Soviet-Chinese relations in his The Strained Alliance: Peking, P’yǒngyang, Moscow and the Politics of the Korean Civil War (New York: The Free Press, 1975), chapters 3 and 4.

30 Allen S. Whiting, China Crosses the Yalu: The Decision to Enter the Korean War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1960), 45-46.

31 In the end, however, Soviet pilots, outfitted in Chinese military uniforms, did participate in the Korean War.

32 O Ch’unggun argues that the Soviets boycotted the Security Council at the time of the outbreak of war out of fear of such criticism by the United States should they veto the resolution to come to South Korea’s assistance. O Ch’unggun, “Han’guk chǒnjaeng kwa Soryǒn ǔi yuen anjǒn pojangi sahǒe kyǒlsǒk: hosaro kkutnan ‘sut’allin ǔi silli oekyo’” [The Korean War and the Soviet Union’s boycott of the United Nations Security Council: A vain attempt resulting in Stalin’s ‘loss’ diplomacy], Han’guk chǒngchi hakhǒe boje 35, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 105-23.

33 This opinion was part of a discussion that took place between the North Korean and Chinese leaders on May 15, 1950 in Beijing, as recounted by Pak Hǒnyǒng in Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 113.

34 Mao made this assumption as part of an exchange of letters between Kim Il Sung and Chinese officials in May 1950, as reported by Shtykov to Soviet officials. Ibid., 108-109.

35 Ibid., 83-84. It was during this visit that Kim sent Kim Kwang-hyop to Moscow to meet with Mao to request that the Chinese leader release Korean soldiers who had fought in China’s civil war (ibid., 88).

36 Wada Haruki, Chōsen sensō zenshi, 111.

37 Ibid., 112.

38 On this day the United States Air force strafed Antung. See Stone, The Hidden History of the Korean War, 90-92. Stone contends that the first Chinese mission of 5,000 Chinese troops was primarily to protect the dams along the Yalu River from U.S. attacks (Ibid., 154-55). Alan Whiting adds that the United States offered compensation for this “mistake,” but two days later Beijing again accused it of firing on Chinese fishing boats in the Yalu River. Whiting, China Crosses the Yalu, 97.

39 Cumings, The Korean War, 25. By this time South Korean troops had pushed to within thirty miles, and the United Nations forces to within sixty miles, of the Chinese border. Stone, The Hidden History of the Korean War, 154.

40 Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, pp. 104-5.

41 The racial factor entered into Mao’s reasoning that Chinese sharing the same hair color as Koreans made their participation more appropriate than the Soviet military. Wada, Chōsen sensō zenshi, 47.

42 Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu, “Occupation Policy and Postwar Sino-Japanese Relations: Severing Economic Ties,” in Democracy in Occupied Japan: The U.S. Occupation and Japanese Politics and Society, edited by Mark E. Caprio and Yoneyuki Sugita (London; Routledge, 2007), 202-204. Peter Lowe notes that MacArthur sent Japanese “volunteers” to Taiwan to assist the Kuomintang in his Origins of the Korean War (London: Longman, 1986), 114-15.

43 Commanding officer John R. Hodge addressed both of these rumors in “Jacobs to Secretary of State: Press Release by General John R. Hodge” (June 16, 1948), Internal Affairs of Korea, 1945-1949, vol. 9 (Seoul: Arǔm, 1995), 493.

44 Kathryn Weathersby, “New Russian Documents on the Korean War,” CWIHP Bulletin 6, 7 (Winter 1995/6), 48.

45 See Roger Dingman, “The Dagger and the Gift: The Impact of the Korean War on Japan,” Journal of East Asian Relations 1 (Spring 1993): 29-55; Reinhard Drifte, “Japan’s Involvement in the Korean War,” in The Korean War in History, edited by James Cotton and Ian Neary (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International, 1989), 120-34; and Michael Schaller, “The Korean War: The Economic and Strategic Impact on Japan, 1950-1953,” in The Korean War in World History, edited by Stueck, 145-76.

46 Drifte, “Japan’s Involvement in the Korean War,” 130. North Korea sunk two of these vessels, another one struck a mine, and yet another ran aground.

47 Japanese-Americans accounted for about 200 deaths, with about 5,000 participating in the Korean War. David Halberstam writes of one Japanese American, Gene Takahashi, who was taken prisoner. When asked to shout out to bring in other prisoners he shouted out in Japanese an opposite message—don’t come in. Halberstam offers that his actions perhaps sent North Koreans the false message that Japanese were fighting among the UN forces. David Halberstam, The Coldest War: America and the Korean War (New York: Hyperion, 2007), 415.

48 Soon after the war broke out, the Japan-based Mindan group issued a call for volunteers to fight in the United Nations forces. Four Japanese were among the 3,000 Koreans who answered this call. According to Reinhard Drifte “thousands of Japanese young people attempted to enlist in the American forces.” Drifte, “Japanese Involvement in the Korean War,” 129.

49 Ōnuma Hisao, “Chōsen sensō e no Nihon no kyōryoku” (Japanese cooperation in the Korean War), in Chōsen sensō to Nihon, edited by Ōnuma Hisao (Tokyo: Shinkansha, 2006), 73-119.

50 John Lewis Gaddis, We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 76-77.

51 These include discussions held between Syngman Rhee and Douglas MacArthur in October 1948 and February 1950, and between Rhee and John Foster Dulles days before the outbreak of conventional war in June 1950.

52 Rhee acknowledged that the proposal to use Japanese-trained Koreans in the South Korean military had drawn criticism from a Major General John B. Coulter, who voiced concerns over the moral problems this might cause. The South Korean president, however, did not see this as a factor of significance. “Memorandum of Conversation by the Secretary of the Army (Royall)” (February 8, 1949), FRUS VII (Far East and Australia), 956.

53 Ibid., 956-58. This is just one of many times in which the South Korean president openly voiced an interest in attacking North Korea. He also broached the idea in February 1950 while in Tokyo, and in a March 1, 1950 speech given before United Nations Commission on Korea (UNCOK). Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 481.

54 See Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 392.

55 “Memorandum of Conversation, by the Ambassador in Korea (Muccio)” (May 2, 1949), FRUS VII (Far East and Australia), 1003-1005. Rhee’s reference to Theodore Roosevelt recalls the American president’s inaction (and encouragement) of Japan’s colonial subjugation of the Korean peninsula from 1905. Franklin Roosevelt “betrayed” Korea by pushing for a trusteeship administration over the Korean peninsula at his 1945 meeting with the Soviets in Yalta.

56 “The Ambassador in Korea (Muccio) to the Assistant Secretary of East Asian Affairs (Rusk) (May 25, 1950), FRUS VII (Korea), 88-89.

57 Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 473.

58 Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 53-56 provides a Japanese translation of this letter.

59 “Memorandum by the Ambassador at Large, Philip C. Jessup” (January 15, 1950), FRUS VII (Korea), 1.

60 “Memorandum by the Department of the Army to the Department of State” (June 27, 1949), FRUS VII (Far East and Australia), 1047-1048. The Joint Chiefs of Staff deemed points three and four to be impractical. Ibid., 1055-1057.

61 Ibid., 1049. Here the terms of the March 1949 Soviet-North Korean agreement appear to be exaggerated. Bruce Cumings cites CIA reports claiming that the equipment that the Soviets sold to the North Koreans was dated, and not useful once the United States entered the war. Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 445-46.

62 “Memorandum by the Department of the Army to the Department of State,” 1050. A number of studies suggest that had peninsula elections been held politicians of leftist suasion would have carried the day. The Soviet ambassador in P’yǒngyang quoted a North Korean statement that South Korea was preparing to invade because it could not survive a peaceful unification. As many as 80 percent of Koreans supported the North Korean system. Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 40. Though the North Korean estimate may have been exaggerated, even the United States apparently recognized that conservatives would lose a general election.

63 The southern Koreans held elections on May 10, 1948 and initiated the South Korean state on August 15, 1948. The northern Koreans declared the birth of North Korea on September 9, 1948.

64 According to Kong Imsun, Syngman Rhee had to resort to forgery to get his list of supporters accepted by the United Nations’ Commission after he missed the deadline. See her “Suk’aendŭl Pankong: Yoryu myǒngsa Mo Yunsuk ŭi ch’inil kwa pankong ŭi ichungchu” (Scandal and Anticommunism: The Duplicity of Mo Yunsuk as ‘Female Intellectual,’ Pro-Japanese, and Anti-Communist), Han’guk kundae munhak yǒngu 17 (2008): 184.

65 “Memorandum (UNCOK and U.S. Policy at the Fourth General [UN] Assembly)” (August 20, 1949) FRUS (Far East and Australia), 1073. We must also note that John Hodge had banned the Southern Korean Communist Party from 1946, thus exiling communists such as Pak Hǒnyǒng to the North.

66 Matthew M. Aid, “US Humint and Comint in the Korean War: From the Approach of War to the Chinese Intervention,” in Richard J. Aldrich, Gary D. Rawnsley, and Ming-Yeh T. Rawnsley, eds., The Clandestine Cold War in Asia, 1945-1965: Western Intelligence, Propaganda, and Special Operations (London: Frank Cass, 2000), 32. Wada Haruki reports that South Korean agents were organized in every northern province (Wada, Chōsen sensō zenshi, 49).

67 Aid, “US Humint and Comint in the Korean War,” 34.

68 The same informant also stated that the railroad connecting North Korea and Russia would be completed by April of this year. G-2 Periodic Report (February 10, 1950), HQ, USMAGIK G-2 Periodic Report (1949. 11. 23-1950. 6. 15) (Chunchon: Institute of Culture Studies, Hallym University, 1989), 293.

69 Dean Acheson, The Korean War (New York: W.W. Norton, 171), 14.

70 These reports began listing the number of casualties suffered by the two militaries, as well as by civilians, from April 1950. Between April 13-20, 1950, for example, it listed as KIA (killed in action) and (MIA) missing in action 17/106 South Korean forces, 130/20 North Korean forces, and 55/3 civilians. HQ, USMAGIK G-2 Periodic Report, (April 20, 1950), 472.

71 Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 503.

72 Shtykov to Stalin, June 21, 1950, Torcov, Chōsen sensō no nazo to shinjitsu, 119. Translation from Weathersby, “Should We Fear This?,” 15. Apparently others were aware of South Korean troop movements around this time, as recalled by former Australian Prime Minister E. Gough Whitlam. See Cumings, Origins of the Korean War, 547.

73 HQ, USAFIK Intelligence Summary, Northern Korea (1947. 4.1-1948. 1. 9) (Chunchon: Institute of Culture Studies, Hallym University, 1989), 31.

74 North Korea predicted that the South Korean military would invade on August 15, 1949, and in early 1950. The Soviet Union and Chinese both cautioned the North to wait for this invasion rather than initiate combat on its own until it became clear that the South would not attack.

75 “Rhee calls on Japanese to Join Anti-Red Battle,” Nippon Times (February 17, 1950), in Migun CIC chǒngbo pogosǒ, vol. 1: Inmul chosa pogǒ [US Military CIC Information Reports: Investigations on People], (Seoul: Chongang ilbo, Hyǒndaesa Yǒnguso, 1996), 242.

76 “Rhee Vows to Recover North Korea,” Stars and Stripes (March 1, 1950), in ibid., 238.

77 “Rhee to Oliver” (March 8, 1950). The Syngman Rhee Presidential Papers (Yonsei University), File 83, #01260015. These papers are also a part of the Robert J. Oliver Papers.

78 Ibid.

79 John Merrill writes that North Korea believed that while in Tokyo Rhee had successfully gained the military assistance he desired. It also accused South Korea of moving toward a military alliance with Japan to use Korea as a “springboard” for attacking the Soviet Union. Merrill, The Peninsular Origins of the Korean War, 173. See also Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, 459-61. Cumings notes that a number of South Korean officials made trips to Tokyo to meet with MacArthur. Ibid., 459.