War Claims and Compensation: Franco-Vietnamese Contention over Japanese War Reparations and the Vietnam War

Geoffrey Gunn

This article seeks to disentangle the complex claims and counterclaims to Japanese war reparations deriving from the period of Japanese rule in Vietnam in the years 1940-45.

|

Japanese Troops enter Saigon September 1940 |

It demonstrates that, alongside Cambodia, Vietnam stands out among the beneficiaries of Japanese war reparations for the huge gap in expectations over compensation issues. Not only was the Tokyo government challenged internationally by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) as the sole legal claimant upon these reparation funds against both the Republic of Vietnam (SRV) and France, it was also challenged domestically by Japan’s major left-wing opposition parties. The issues were complicated by the fact that the major Japanese reparations-aid project, a hydro dam, was crippled by the DRV’s southern arm, the Viet Cong. But even prior to the French invention of the State of Vietnam in 1949, France made claims upon Japan for war damages and reparations, as well as for unpaid loans and debts. The multi-sided diplomatic contest also engaged Washington and not all issues were resolved by the San Francisco Conference in 1951 or the emergence in 1955 of the independent Republic of Vietnam. Although Emperor Bao Dai had been restored in 1949 by the French as head of a partly autonomous Associated State of Vietnam, in backing the Republic of Vietnam, the Americans turned to another figure who had served under the French, namely Jean Baptiste Ngo Dinh Diem.

|

Time Magazine Cover of Ngo Dinh Diem |

A staunch anti-communist Catholic ally, Diem would eclipse Bao Dai in a rigged election in October 1955, becoming the President of the Republic of Vietnam until his assassination at Washington’s behest in 1963. With the emergence of the Republic of Vietnam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, and the Kingdom of Laos as independent states following the Geneva Conference settlement (1954), the three countries virtually stepped into the shoes of France in negotiating their future relations with Japan, war reparations included. Just as the three Indochinese states established diplomatic relations with Japan on their own terms, encouraged by the United States with Cold War considerations to the fore, France looked to the future in its relations with Japan, putting aside a host of acrimonious wartime claims and recriminations. On the other hand, Japan sought to expand its political, economic, and commercial links with the three Indochinese states, while also entering into a commercial relationship with the DRV, under the formula of “separating politics from economics.” But Tokyo neither recognized the DRV nor provided reparations. This article problematizes the interwoven themes of French war damages claims, Vietnamese reparations demands, and Japan’s contested postwar political and business links with Vietnam in support of US goals.

Key elements of Japan’s war reparations as well as ODA programs are relatively well understood (See Nestor 1992). Indonesia, for example, is well represented with the study by Nishihara Masashi (1976) on Tokyo-Jakarta relations between 1951-66. However, the literature on Indochina is more select or fragmented, as with Le Manh Hung (2004), who has examined Japan’s “special Yen” demands, Masaya Shiraishi (1990) with a summary account of postwar reparations, and books focused upon Japan and the “Vietnam War,” as with Thomas J. Havens’ evocatively-titled Fire Across the Sea and, in French, the more general work by Guy Faure and Laurent Schwab (2008).

Drawing upon a range of French (Ministère des Affaires Etrangères or MAE) and Australian (National Archives of Australia or NAA) archival materials, this article takes the Indochina compensation case, Vietnam in particular, as a particularly problematical one, where even the beneficiary of Japanese war reparations (the Republic of Vietnam) was challenged, not only by the DRV and its international backers but, domestically, by a strident and highly vocal anti-war movement. In short, it seeks to establish links between France’s postwar compensation claims, US “reverse course” on compensations in line with rising Cold War perspectives, France’s climbdown in its need for allies in the face of North Vietnamese intransigence, and Japan’s reparations-cum business negotiations with the American-backed Republic of Vietnam. The article is divided into four sections. First, I will discuss French war damage claims on Japan. Second, I will focus upon the San Francisco Treaty of 1951 insofar as it affected relations with France and the Associated States of Indochina. Third, I will examine the diplomatic and trade relations between Japan and the Indochinese states. Fourth, I will discuss the background and actualization of Japan’s reparation agreement with, especially, Vietnam. I conclude by discussing the “Vietnam War” effect on the Japanese economy.

French War Claims

In early 1946, as France consolidated the restoration of its colonial order in Vietnam in the wake of the Japanese surrender, a special commission was established to assess war damages inflicted by Japan in Indochina. Known as the Commission Consultative des Dommages et des Reparations. The Commission’s interim report offered provisional estimates of damages inflicted between 1940-45, as well as specifying damages of the Japanese occupation on both French and local Indochinese interests. It concluded, “Japan through its occupation, through bombardments and conflict, contributed to the annihilation of the fruits of 50 years of labor.” While acknowledging that the conduct of the war in Indochina was not exactly analogous to that of Germany vis-à-vis France, it sought to apply the criterion for war damages as determined by the Commission des Reparations (4 March 1921) after World War I in determining German war damages (anon, Evaluation des Dommages, 1946).

The computations are complex but included claims for “spolations,”or pillage, destruction (inflicted upon French and Allied forces), other damages (goods, persons and other costs imposed by war operations), damages to private property, and special charges. Notably, as the report emphasized, pillage by Japan in Indochina commenced even prior to the declaration of a state of war. As the report pointed out, these were not only French losses, as “the purchases conducted in Indochina by Japan were, in reality, supported by the Indochinese Union [the Indochinese countries].” In other words, there was a diminution of economic patrimony “without real counterpart and to the single benefit of the occupier.” Notably, Japan manipulated the rate of exchange to its benefit. As the report made clear, extortion of piastre via the Yen “credits” system (as explained below) should be the central feature of future reparation claims upon Japan (anon, Evaluation des Dommages, 1946). As discussed below, compensation for the Yen credits would not only be vigorously prosecuted by France, but also by Thailand and China which made parallel claims.

Otherwise, the French Reparation Commission report offers an itemized lists of damages and claims upon Japan for compensation, as with, for example, railways, the French merchant marine, French property in Indochina/China, and “damages to persons.” A parallel reckoning itemizes claims (or special charges) associated with the Indochinese countries. In summary, the total damages suffered by France and the Indochinese countries stemming from the Japanese occupation were reckoned at 2,761 million piasters at 1939 value, or 13,800 million piasters (1945 value). Rounding to 14 milliard Indochinese piastres, this amount equaled 235 milliard French francs, or the equivalent of 2 milliard or US$ 2 billion dollars (anon, Evaluation des Dommages, 1946). France would press its reparations claims to the eve of the San Francisco Conference in early 1951, expressly demanding US$2 billion compensation from Japan for wartime damages incurred in Indochina. As explained below, however, not one centime would ever be paid to France.

The Far Eastern Commission

France’s claims on Japan were not just a bilateral exercise but, as with other Allied countries, would fall under the ambit of a multilateral organization. The lead body concerned with Japan’s post war reparations, the Far Eastern Commission (FEC), emerging out of the Moscow Conference of December 1945, numbered the following member countries; the USSR, the UK, the US, China, France, the Netherlands, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and the Philippines. With headquarters in Washington, the object of the FEC was to formulate principles and manners to assure that Japan would meet its reparation obligations, and to examine the demands of each member country. The FEC worked with the Allied Council in Japan, SCAP, and its hierarchy. Consequently, the US played a determinant role from the first meeting of the FEC held on 18 July 1946. Decisions taken at this meeting related to the restitution of stolen property, namely machinery, gold, cultural objects, and ships. France was represented by its Ambassador, P.E. Naggiar. (Nouvelles Documents,Etudes No.1, Comite Interministerial de l’Indochine). Undoubtedly, this meeting raised expectations of the potential recipient countries – France, China, the Philippines and Australia – as to future claims upon Japanese plant, machinery, and other industrial goods. Further meetings of the FEC (14 August) also pronounced upon the “reduction of Japan’s war potential.” In February 1947, discussions at the FEC on “advanced transfers of Japanese reparations” had already crystallized. However, as the French member remonstrated, at that stage, French Indochina and India had not been listed as recipient countries and, in agreement with the Soviet member, urged inscription of all eligible countries in the advanced reparation transfer program (FEC, 11 February 1947, “Advanced Transfer of Japanese Reparations.” Note by the Secretary-General). In June 1948, the FEC reached substantial agreement on the level of industry needed to meet Japan’s peaceful needs. But the FEC process had already been stalled while awaiting a US statement.

No quick consensus was reached by the FEC as to the precise modalities of Japanese war damage compensation, especially relating to the issue of shares among the would-be recipients. From an early date, US representative Edwin Pauley had made it clear that the US would receive reparations from Japan en nature rather than in cash (Times of India, 24 September 1945). As explained by a US aide-memoire of 11 May 1949, from the earliest days of the occupation, the US was guided by a desire that victims of Japan’s occupations would receive Japan’s capital resources as reparations without jeopardy to its ability to meet its own “peaceful means.” Notably, on 1 April 1946, the US informed the FEC that designated quantities of facilities deemed superfluous for Japan’s needs should be immediately available for reparations. But the US also began to reevaluate its position on the question, based upon a number of assumptions and (unstated) biases. In the new interpretation, the US argued, Japan was facing demographic pressure which placed great strain upon existing resources. Moreover, the US was carrying Japan’s budget deficit. “Further reparations from Japan would jeopardize the success of the Japanese stabilization program.” It was also argued that Japan had already paid substantial reparations through the expropriation of its former overseas assets (Korea; Taiwan; Manchuria). Unilaterally, the US declared that it had rescinded the directive of 4 April 1947 “therefore bringing to an end the advanced transfer program.” The US also withdrew its proposal of 6 November on Japanese reparations shares (NAA A 461 H50/1/6: Reparations from Japan,” Embassy of the US, Aide-Memoire, Canberra, 11 May 1949).

FEC member countries received the US aide-memoire with coolness (Australia), bitter opposition (the Philippines, as with the Romulo statement of 26 May 1949); and with outrage at its “illegal and immoral” stand (China), which deemed the US position “incompatible with a series of international agreements” and “unjust to victims of Japanese aggression” (NAA A 461 H50/1/6 cablegram, Australian Embassy, Washington, 27 May 1949).

The truth is, however, that “reverse course” was already in process. A creature of the Cold War, Washington’s reverse course on Japan was shorthand for the complex diplomatic pact whereby Japan (and its war criminals) would be forgiven and even rehabilitated (even alongside the major industrial conglomerates that fueled Japanese arms buildups), in a Faustian bargain that would reposition Japan as a US ally in the struggle against communism. Facing the Chinese communist thrust, the Chinese Nationalists had grasped at the same straw, as early as 1945 offering new life to Japanese war criminals with the requisite military skills. As it became clear to France that the Viet Minh were “in bed” with the Chinese communists, the French Fourth Republic (1946-58) would likewise begin to shift towards signing a peace treaty with its former enemy.

French Claims on Indochina Special Yen

In general, all Japan’s unpaid foreign loans, including the unpaid loan contracted by the City of Tokyo in 1910 (France suspended all repayments on this loan in 1940), were under investigation by the FEC. But the major economic-financial issue besetting France and Japan was the question of Special Credits including Special Yen. During the war years, Japan had transferred large tranches of counterpart funds out of French Indochina offering the counterpart of Special Yen parked in the Yokohama Specie Bank in Tokyo by the Banque de l’Indochine. Such included “Yen rice” under which Japan plundered Indochina’s cereal resources (See Le Manh Hung 2004: 110-2). The parallel, as far as French opinion was concerned, was the “clearing system” imposed by Nazi Germany over occupied France. As the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs signaled to their mission in Tokyo in 1953, they attached more weight to a resolution of the Special Yen issue than the reparation and damages restitution issue. This was all the more so as the French had, by 1953-54, failed to sign an interim agreement with Japan over damages which in any case were now being taken up by the Vietnam-Japan negotiations in which France had a much reduced influence (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109).

From the outset, however, the French government and SCAP differed over this issue as well. Notably, the “Special Yen” account had been opened in April 1943 in application of the accords of 20 January 1943 (signed with the Laval Vichy government), an arrangement that saw the French Indochina administration via the Banque de l’Indochine and its branch in Tokyo deposit both Yen, dollars, and gold with military-linked banking institutions in Tokyo, notably the Yokohama Specie Bank right up until the end of the war. At war end, the Banque de l’Indochine held with the Yokohama Specie Bank a Special Yen account of 848,414,008.99. It also held a US dollar account of 2,035,674. 67. With respect to the Bank of Tokyo, 33,658,813.70 grammes of gold were earmarked, otherwise accruing from US purchase of Indochina rubber (1941-42) (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109, R. Douleau, Conseiller Commercial de France, Washington, à Ministre de Finance, 15 Fev. 1946).

To this day, Vietnam recalls in no uncertain terms the despicable drain upon the local economy imposed by “fascist” Japan through its impositions upon “imperialist” France (anon: History of the August Revolution, 1979: 41). However, given the role assigned for France by the FEC process, Vietnam was never even vested with the right to reclaim these monies obviously including interests of national patrimony. (See Table I)

Table 1. Monthly Payments from Vichy France to Japan (1940-45) in Piasters

| Year | Amount | January-March |

| 1940 | 6,000,000 | 2,000,000 |

| 1941 | 51,000,000 | 4,000,000 |

| 1942 | 86,000,000 | 7,000,000 |

| 1943 | 111,000,000 | 9,000,000 |

| 1944 | 363,000,000 | 30,000,000 |

| 1945 | 90,000,000 | 30,000,000* |

[not including 780,000,000 paid by the Banque de l’Indochine to Japan from March-August 1945]*

Source: anon: History of the August Revolution, 1979: 41.

But just as the French Fourth Republic moved to gain restitution of Special Yen accounts lodged in Japanese banks in the early postwar period, so it came into conflict with a largely disinterested SCAP bureaucracy in Tokyo. Notably, until suspended under French diplomatic protest, SCAP immediately moved to dissolve the Yokohama Specie Bank. Neither was it helpful to French interests that, on 27 December 1945, SCAP also commenced the liquidation in Tokyo of the local branches of the Banque de l’Indochine along with the Banque Franco-Japonais. The French were also vexed that General MacArthur himself would not explain why he stonewalled on the Special Yen issue. More generally, the French sought to decouple the Special Yen issue from the reparation question (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109).

The American attitude is revealed in the text of conversations between French Ambassador in Tokyo, Zinovi Alekseïevitch Pechkoff, and MacArthur and staff. Basically, SCAP/Washington contended that the French treaties (with Japan) were signed by Vichy France and were considered null and/or were of the nature of private transactions. The American side also did not wish to privilege France over a host of other claimants (notably, China and Thailand) (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109). There was a certain disingenuous logic on the part of the Americans, especially as Washington hosted a Vichy Embassy through at least December 1942, and US-Vichy relations – especially under President Roosevelt – were on a “day to day” basis. The Provisional Government of the French Republic, headed by Charles de Gaulle, was only recognized by the US on 23 October 1944. The American position offered ammunition to the Japanese side in future dealings with the French.

The French Climb Down and Diplomatic Push

French Foreign Affairs documents reveal that, from mid-1947, their officials in Tokyo had entered into discussions with members of the Cercle d’Etudes Economiques Franco-Japonais. Members included former Japanese ambassadors, Kurusu, Kuriyama and Yokoyama Masayuki, the latter installed as Resident of Annam following the Japanese coup de force. The three former wartime diplomats declaimed that Japan had “great responsibility” for “troubles” in Indochina and wished to renew relations with Indochina. Yokoyama, especially, dwelt upon the considerable economic potential of Indochina and foresaw future Japanese involvement (MAE Asie Oceanie Indochine 284 Delegation Français des Reparations et Restitutions, Tokyo, 24 Juillet 1947).

The diplomatic recognition issue was taken up in earnest in Paris in early 1948. The argument in favor, as outlined in a brief position paper, acknowledged that, in the coming years, Japan would emerge as “the pivot around which Far Eastern political and economic issues would revolve.” Japan was a looming exporter of industrial material to the Far East and would comprise a market for Indochinese rice, coal, minerals, phosphate, salt, wood, etc.. The paper predicted that Japan would take its place within the Pacific economic system and, given instability in China and the Philippines, Indochina would look to Japan to support its industrialization. As recommended, it was in French interest to establish political contacts between Indochina and Japan. And, to this end, it was imperative to place an “autonomous” Indochina representative in Japan, first with SCAP, and then with the Japanese government. The suggestion was for a French official answering to the so-named French High Commissioner in Saigon. The possibility of a Vietnamese representation abroad was then regarded as “one of the most delicate issues” in Franco-Vietnamese relations (MAE Asie Oceanie Indochine 284 “Note sur la Representation de l’Indochine au Japon,” Paris, 18 Janvier 1948). In any case, it would take a major international conference to break the logjam on the restoration of diplomatic relations between France and Japan outside of SCAP control.

Still, France was obliged to work through SCAP. Although Vichy France had maintained an accredited Embassy in Tokyo and consulate in Yokohama through the war years (at least until March 1945), technically the first official postwar contact between Japan and France outside of SCAP auspices, took place at San Francisco in 1951. While the Conference outcome would see the restoration of full diplomatic relations between Paris and Tokyo, France also repeated its claims at San Francisco for US$2 billion in compensation from Japan.

France and the San Francisco Peace Treaty of September 1951

Some background is necessary. Following a visit to Paris in early June 1951 by John Foster Dulles, serving as special envoy of US President Truman, the broad outlines of French conditions for its participation in the proposed peace treaty with Japan were clarified, just as US expectations were made known. The basic French demands were made clear to Dulles in a meeting with the French President Vincent Auriol. Dulles went out of his way to mollify France as to any revival of Japanese “political imperialism.” Tellingly, he pointed out, Japan would “integrate” its forces with those of the US. He also made it clear that a treaty with Japan would not prejudice any future (French) negotiations with Germany. Auriol, on his part, sounded out Dulles’ view on the participation of the Associated States (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) in the San Francisco treaty negotiations. Dulles saw no objection, but preferred the formula of bilateral relations between the Associated States and Japan. Auriol demurred, offering two outcomes, one in which the Associated States gave mandate to France to sign in their name, or the other in which the Associated States and the French Republic separately sign with Japan (at San Francisco). These views were echoed by Alexandre Parodi, secretary general of the French foreign ministry in conversations with Dulles and in subsequent press releases (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 52, Audience de M. Foster Dulles par M. Auriol).

As Dana Adams Smith summed up the conversations in the New York Times (12 June 1951), where Dulles wished a “treaty of reconciliation,” Parodi wished for reparations. Specifically, France demanded US$ 2,000,000,000 reparations from Japan including repayment of three pre-war loans; compensation for the destruction of French property including plant; compensation for French shipping, along with rubber, cotton and other goods seized by Japan. Moreover, to win US consent, France had backed down on its earlier proposals that both China and the USSR participate at San Francisco.

The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed by 48 Allied nations and Japan in San Francisco on 8 September 1951 and coming six years after Japan’s surrender, facilitated Japan’s return to the international community. Under Article 11 of the Treaty, Japan was obliged to accept the judgments made by the International Military Trial of the Far East (IMTFE), as well as judgments made by other Allied War Crimes courts outside of Japan. But China, the Soviet Union, India, Burma and Korea were not signatories to the Treaty and the DRV was not invited. Thanks to French patronage, however, among the signatories were the Bao Dai government, as well as the Cambodian and Lao governments. With the Treaty coming into force on 28 April 1952, Japan then entered into diplomatic relations with the Bao Dai and, in turn, the Diem governments. The Bao Dai government ratified the San Francisco Treaty on 8 May 1952. On 10 January 1953, the three governments notified the Japanese government that they agreed to open diplomatic relations. However, as discussed below, the successors to the Bao Dai government postponed the actual opening of a legation until after the conclusion of a reparations agreement in May 1959.

|

Emperor Bao Dai |

More broadly, under the terms of the San Francisco Treaty (14th article), Japan was obliged to meet the reparations demands of former occupied nations. Accordingly, Japan signed a series of reparation agreements (baisho) with Burma (November 1954); the Philippines (May 1956); Indonesia (January 1958); and, eventually, South Vietnam in May 1959. Cambodia and Laos, as explained, would abandon the right to receive reparations, although in October and March 1959, Japan agreed to provide them with economic and technical aid.1 Japan did not pay reparations to Thailand, but agreed to make a payment for the liquidation of Special Yen (agreement of July 1955, revised January 1962). As Nestor (1992: 121-2) contextualizes, by tying all this aid to purchases of Japanese goods and services, “Tokyo opened up vast export markets as each country became dependent on Japanese corporations for spare parts, related products and technical assistance.” Moreover, in line with Cold War logic, Washington used every possible means to promote Japan’s economic penetration. South Vietnam was in the front line.

Japan and the Associated States

Not only did France support the participation of the former Associated States in the San Francisco process, it took for granted that they would individually enter into diplomatic relations with Japan “at an opportune time” (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 15, file 060 Tel, Paris, Etassocies, 16 Sept 1952, no.910/911 to Minetassocies, Saigon). In November 1952, Gaimusho made it known to France that it wished to establish diplomatic relations with the Associated States. The priority was Saigon followed by Phnom Penh, and Vientiane. With these states represented at San Francisco, the Quai d’Orsay did not feel it prudent to oppose this plan. In fact, it was Cambodia which, in a note of 26 May 1952, first approached Japan (prior to the Japanese request) to establish diplomatic relations. In October, Vietnam solicited and obtained French government approval to establish relations with Japan. Even so, Vietnam dragged its feet. Its president Nguyen Van Tam had revealed a repugnance at moving any time soon on the matter, and gave the appearance of linking it with the reparation question. Jean Letourneau, Minister for Overseas France, believed it both in the interest of France and Vietnam to move ahead. (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 15 Note for the Secrétaire général, 24 Nov 1952, #073).

In January 1953, as Gaimusho signaled, Cambodia sought the establishment of relations at an early date. Vietnam had also expressed in-principle agreement. Laos was also in agreement but wished the future Japanese embassy in Saigon to be accredited to King Sisavang Vong and had no immediate intention to establish an embassy in Tokyo (MAE Asie Océanie #78 Japon 95). Irritated at the inconclusiveness of the Vietnamese side, Gaimusho stepped up its pressure on France to intervene and France appears to have brokered the agreement on diplomatic relations between the two countries. France also helped to broker the establishment of a Cambodian mission in Tokyo (MAE Asie Océanie #78 Japon 95 tel. Paris, 13 Avril 1953).

Even so, as reported, the Vietnamese government would not entertain the establishment of diplomatic relations until negotiations on the reparation question were underway (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109, MOFA tel. 30 Juillet 1955 to Bangkok #093). On 22 September 1954, as the French side learned, a Japanese Diet delegation visiting Saigon was received correctly but “sans chaleur” (without warmth). Finally, on 17 June 1963, as the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry informed Paris, it had agreed with a Japanese approach to open diplomatic missions in each other’s countries, without subordinating the issue to the reparations question. In turn, this démarche was passed on by the French authorities to Gaimusho on 28 June (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109,Etat du Vietnam, MOFA no.1787-DAP, Saigon, 17 Juin 1954, “Note” #104).

The Debt Issue Revived

Still, the debt issue dragged on. In a Note Verbale of 8 December 1954 delivered to Gaimusho, France called attention to the two outstanding créances (claims/debts). The first was for Yen 1,315,275,813.03 and the other was for US$ 479,631.19 “possessed by the French government with the liquidation of the Yokohama Specie Bank.” France wished a speedy resolution of the problem and informed Tokyo in less than diplomatic language that the problem was harmful to the creation of sound “economic relations between the two countries.” France proposed negotiations (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109). In other words, it was sticking to its claims for damages incurred between 1940 and 1945.

But the Japanese side would have none of this, having made its position crystal clear at the fifth session of the Japanese-Vietnamese negotiations relating to ship salvaging and reparations held on 7 July 1953. At that forum, the French representative asserted that he considered 8 December 1941, the day that the London-based French National Committee (under Charles de Gaulle) declared war on Japan, as the day that a state of war existed between France and Japan. The Japanese delegate retorted that all operations effected by the 8 December proclamation were without legal foundation and, moreover, under [Chapter V “Claims and Property”] article 14b of the Treaty of San Francisco, France had renounced its right of reclamation of damages resulting from the war. If France wished, Japan would explain its case in Tokyo (MAE Asia Océanie Japon 109, M. Morand, Conseiller Commercial, Ambassade de France au Japon to Ministre de Finance, Paris, 17 Mar 1955, “Recouvert de la créance de Trésor français sur le Yokohama Bank”). This was basically correct. Echoing American reservations over the FEC process, Article 14 stated, inter alia, that Japan lacked the resources to make complete reparation, therefore (14b) “Except as otherwise provided in the present Treaty, the Allied Powers waive all reparations claims of the Allied Powers.” Analogous arguments were presented to the visiting Thai foreign minister in Tokyo in March 1953, namely that Japanese-Thai accord had been mutually dissolved, and that no force had been exercised in the wartime pact, only moral suasion.

Another outstanding issue was compensation for the near total damage suffered by the French Embassy in Azabu along with the Ambassador’s residence destroyed by two American bombing raids over Tokyo on 23 and 25 May 1945. On 9 July-10 August 1946, the French mission in Tokyo filed claims with SCAP for Japanese (not American) compensation for the costs of reconstructing the Embassy premises. As SCAP replied on 15 October 1946, it would not press the issue. But, it also advised, “make the cost a matter of record for future settlement.” Accordingly, on 8 February 1952, and citing protocols prescribed at the San Francisco conference (Article 15 appears to fit), France pressed the Tokyo government to offer Yen 40 million compensation to facilitate the reconstruction of the Embassy (MAE Asie 1946-1955 Japan I). There is no record that France ever gained this compensation.

As an internal French memorandum of 17 March 1955 revealed, the claims issue was going nowhere. In the interim, no doubt mindful of US reservations, the French decided to cut their losses and reduce or restrict their claims to debts owed by Japan stemming from its Special Yen manipulation between 30 August 1940 to 9 December 1941, that is, prior to the declaration of war pronounced by the Free French under General de Gaulle (MAE Asie Océanie Japon 109, MOFA to Ambassador, 8 Dec 1954 Tokyo). Notably, on 30 August 1940, France had agreed under duress to facilitate the stationing of Japanese troops in Indochina and to offer credits to cover their expenses. In other words, France now backed away from claiming debts accrued during the period of state of war (or the long three-year period of Vichy-Japanese military cohabitation in Indochina). In other words, France now backed down from the lion’s share of massive claims. It did not make this position public but was prepared to abandon its blanket claims in the course of negotiations.

This was obviously a major climbdown but it also reflected the changing sovereignty stakes inside Indochina, arising out of the San Francisco Peace Treaty and France’s insertion in the Western Alliance. It was, moreover, the legal foundation upon which the French Fourth Republic would effectively rebuild its postwar diplomatic relations with Japan. From the present-day perspective of high tourism, cultural platitudes, and some genuine mutual admiration, it is as if practically no-one on either side actually recalls these rather sorry events.

Japan-Republic of Vietnam Economic Relations

The evolution of post-war relations between Japan and the State of Vietnam (1949-55) and, in turn, the Republic of Vietnam (1955-75) might be described as tentative, belated, and strained. Reaching back to July-August 1954, the Japanese ambassador in Bangkok, Ohta Ichiro, reportedly visited Saigon in connection with preparations for an exchange of ministers between Japan and Vietnam. Australian officials learned from a Kyodo News Agency correspondent in Saigon that the ambassador believed that Japan should observe the (Geneva Accords) truce and the communists from close quarters. He also apparently believed that, if a general election was held, this would result in a victory for the communists (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, P. Hill. 3rd secretary, Australian Embassy in Japan, 5 August 1954, Japan: Relations with Vietnam).

On 22 June 1954 or shortly after the Geneva Agreements, the Japanese Foreign Ministry finally received Vietnamese written consent to exchange ministers and, as mentioned below, the first Japanese minister (to the Bao Dai government), Konagaya Akira, was appointed in February 1955. In March 1955, Nguyen Ngu Thu became the first Vietnamese minister appointed to Tokyo. In a short time, the legations were raised to embassy status. At the same time, following US lead, Japan’s diplomacy completely neglected the DRV (Shiraishi 1990: 5)

In reporting the meeting in Saigon of a Japanese economic delegation with the Union Syndicales des Commercants et Industriels Vietnamiens at the Chamber of Commerce, the semi-official Vietnam-Presse (15 September 1955) noted an increasingly strong economic current between Vietnam and Japan over previous years. Notably, consignments of Japanese goods were now entering the Vietnam marketplace. The report also signaled that, from early 1955, Japan was actively preparing to sign a commercial treaty with “free Vietnam” designed to replace the pre-independence agreement concluded by the French government still in force.

As the Australian Legation in Saigon reported in early 1956, there were rumors of the entry into Vietnam (with US approval) of Japanese experts in fisheries and engineering. However, President Diem had apparently changed his mind out of irritation that the Japanese ambassador did not call upon him prior to return to Tokyo for consultations. As the Australian report continued, Diem was also inconsistent insofar as he had already granted permission to a Japanese engineering company to survey for a large hydroelectricity scheme and had, accordingly, been granted a contract (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part 1, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, Australian Legation, Saigon, 28 January 1956). A reference to the future Na Dhim dam project, as mentioned below, it would also come to the center of Diem’s future reparation negotiations with the Tokyo government.

The Contrast With Cambodia

On 26 May 1952 (Note 1184-DPG), Cambodia under King Sihanouk ratified the Treaty of Peace with Japan (the San Francisco Treaty). In acknowledging this ratification, on 4 July 1952 Gaimusho responded in a note to the Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that it wished to open full diplomatic, commercial, and trade relations (MAE Asie Océanie, Japon 95, Gaimusho, Tokyo, 4 Juillet 1952). On 25 August 1953, Gaimusho made it known that its new embassy in Phnom Penh would be headed by Ambassador Araki Tokizo as chargé d’affaires. Paris clarified that Cambodia would be represented in Tokyo by the French Embassy (MAE Asie Océanie, Japon 95).

Writing in the Asahi newspaper of 4 October 1954, under the headline “Cambodia is Japonophile,” author Ishizaki observed that, not only did goodwill exist in Cambodia towards Japan, but that it was “one of the few countries in Southeast Asia where hatred towards Japan was not displayed.” Citing chargé d’affaires Yoshioka, Ishizaki declared that, from the king and ministers down, all displayed affection towards Japan. He attributed this benign state of affairs to the work of the Suzuki brothers (Shigenari and Shigemichi) who had taken up residence in Cambodia in 1944 as head of the Japanese cultural mission, one a Keio University graduate, another an ex-Paris trained artist. As an example of Cambodia’s links with Japan, Ishizaki observed, the king (Sihanouk) had secured airplanes from Japan and sought engineering assistance to construct a port at Ream (in the Gulf of Siam) to lessen dependence upon Vietnam. He also noted that Japan had contracted 120,000 tonnes of maize the previous year (MAE Asie Océanie, Japon 95).

As French officials well understood, Japan had gone out of its way to cultivate special links with Cambodia in general and King Sihanouk in particular. Notably, Sihanouk made a first visit to Japan in 1952, followed by a second in 1953, becoming the first Asian head of state in the postwar period to receive an audience with the emperor. It was also noteworthy that Prince Norodom Kantal was nominated to head the first Cambodian mission in Tokyo (MAE Asie Océanie, Japon 95 Levi, Ambassador de France à MOFA, Paris, 14 Jan 1955).

The Japanese press also privileged links with Cambodia, as with the Yomiuri (15 January 1954) article “Cambodia: A gold-mine to exploit,” authored by “old Indochina hand,” M. Matsushita, and vice president of the Japan-Cambodia Friendship Society. According to the article, in highlighting a visit to Cambodia by a Japanese delegation, Sihanouk declaimed that, “Japan was the object of his love” and, accordingly, it was in this spirit that Cambodia had renounced Japan’s reparation obligations. Noting that trade only reached 10 million dollars annually, the article predicted that the advent of a commercial treaty would see business surpass that figure (MAE Asie Océanie, Japon 95).

The Uemura Mission to Cambodia

Visiting Japan in January 1955, a South Vietnamese economic delegation consulted with business groups, the Japanese Foreign Ministry, and the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) officials, about the possibility of concluding a trade agreement between Japan and Vietnam. Meanwhile, a Japanese economic delegation headed by the vice president of Keidandren (and future president) Uemura Kogoro visited Cambodia. Also representing coal mining interests, Uemura was president of the Cambodia-Japan Friendship Society formed in Tokyo in September 1954. This was a high power mission joined by representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, MITI, Forestry, Transportation, the Export-Import Bank as well as Mitsubishi Mining Company. As Australian officials interpreted, the Uemura mission sought prospects for joint enterprises to develop natural resources in Cambodia, while looking ahead to offering technical assistance (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, P. Hill. Australian Embassy, Tokyo, 27 January 1955, Japan: Economic Relations with Indochina).2

Upon his return to Tokyo from Phnom Penh on 8 February 1955, Uemura claimed that Cambodia had accepted aid from Japan under the auspices of the Colombo Plan, notably in irrigation works and agriculture. Joint exploitation projects were envisaged, especially in light industry as, for example, a bicycle tire factory using local rubber. Scholarships for Cambodian students in Japan were also under consideration (MAE Asie Océanie, Japon 95, Ambassade Levi à MOFA, 11 Fev 1955, 143-44).

The Sihanouk Visit to Tokyo of January 1955

Sihanouk visited Tokyo again between 4-10 January 1955, leading to the signing of a Traitié d’Amitié. Noting that Cambodia was one country occupied by Japan “ni cicatrice ni rancune” (without scars or bitterness), Sihanouk was locally feted as the first Asian head of state to enter into commercial relations with Japan sans arrière pensée (with no hesitation). As French Ambassador to Japan Levi observed, Sihanouk’s visit was also full of symbolism, as with his renunciation of reparations and the act of remitting to the Japanese Red Cross 1,000 Sterling that Cambodia had received as indemnity for prisoners of war (In turn, the Japanese Red Cross proposed to use this amount to send medical supplies to Cambodia). Among those attending an officialized reception for Sihanouk in Tokyo were General Managi, former Japanese Imperial Army commander in Cambodia at the time of the March 1945 coup de force, along with a Colonel Ogiwara, presented as having saved the Prince’s life at the time of the return of French forces to Phnom Penh (although we have no record of that). Also attending was a Captain Tadakuma, recently returned to Japan from Cambodia, having served as instructor of young Cambodian nationalists (this rings true). Yet another was a Professor Kodaka who had “taken over” headship of the prestigious Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient in Cambodia, and author of a 4,000-page history of Cambodia “redressing the errors of the colonialists,” while underscoring the parallels between Japanese and Cambodian culture. In his speeches, Sihanouk had, variously, reiterated his support for neutrality in foreign policy, rejected membership of SEATO, upheld the five principles of coexistence, and declared adherence to the principle of Asian solidarity (Ibid).

Duly signed on 9 December 1955 by Sihanouk (since March 1955 abdicating in favor of his father and assuming the title of prime minister) and Japanese Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru, the Traité d’Amitié negotiations between Japan and Cambodia also involved discussion on the following salient points. First, the Prince envisaged a riel support plan to offset Cambodian imports from France. Second, he unveiled a plan for Japanese emigration to Cambodia. This was to be of the Brazil-type, following the precedent adopted by the Latin American country towards Japanese immigration, notably suggesting a total assimilation. [However, as the French understood, this plan depended upon considerable financial support from the Japanese government, hardly likely with costs estimated at 700,000 yen for moving a family]. Summing up the import of the Sihanouk visit and the signing of a Treaty of Friendship, the French ambassador observed that, if the propositions were well received in Japan, however ambitious, the trip also showed Sihanouk’s determination to cut an independent course (MAE Asie Océanie, Levi à MOFA, 13 Dec 1955; #172-5).

To be sure, the French could not have been exactly happy to observe the King-turned-Prince-politician cohabiting with a real “rogues’ gallery” of old wartime Indochina hands during his Tokyo visits but, whatever else might be read into Sihanouk’s flirtation with early postwar Japan, it is palpable that he was setting down a future independent course in Cambodia’s foreign policy that would see him align with most of America’s past, present, and future enemies. Meantime, he could play off French aid with Japanese.

Background to the Vietnam Reparations Agreements of 13 May 1959

As Shiraishi (1990: 14) interprets, and as will be embellished below, Japan’s eagerness to fall in line with San Francisco was not so much out of moral angst but as a device to expand Japan’s economic influence over the non-communist countries of Southeast Asia and, at the same time, restore Japan’s domestic economy. But as with the Philippines and Indonesia along with the South Vietnamese, Shiraishi continues, Japan could not restore those economic links with Southeast Asia until it fulfilled its reparation obligations. In other words, reparations became at the hands of the Southeast Asian elites, a precondition for Japan’s future activities in Southeast Asia. The Southeast Asian nations also wanted capital goods to expand their own economies rather than imported consumer goods. Hence, reparations spread out over years, were not paid in cash or capital goods but rather in Japanese products and services, alongside loans, in other words tied aid. As understood, Japanese reparations “paved the way for future economic penetration into the recipient countries.” Products and services provided as reparations stimulated demand for more goods from Japan. In this argument, reparations paved the entry of Japanese business into Southeast Asia while trading companies were able to revitalize their commercial activities to a far greater extent than in the prewar setting. As discussed below, although the Japan-Vietnam reparations agreement was signed on 15 May 1959 coming in effect on 12 June 1959, its passage was deeply troubled.

The Konagaya Conversation

As a first step on the way to signing a reparations agreement, an interim agreement concerning reparations was initiated in September 1953 (Shiraishi 1990: 5). This is revealed in conversations between Japanese ambassador Konagaya Akira and the Australian Legation in Saigon of 15 February 1957. Appointed in February 1955, Konagaya became the first minister appointed to the Republic of Vietnam. Another wartime Vietnam hand, Konagaya had been Consul General in Annam at the time of the coup de force. Evidently, talks on reparations began four years earlier in Tokyo with the French Embassy assisted by a Vietnamese representative. The interim agreement was concluded with the signing of an agreement under which Japan would contribute US$ 2,500,000 to effect salvaging of 70 Japanese ships sunk during the war, mainly in the Vung Tau-Saigon area. The scrap from the ships would be handed over to Vietnam (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, Blakeney, “Japanese Reparations,” reported conversation with Japanese ambassador Konagoya, Australian Legation, Saigon, 16 Feb. 1957).

However, with the advent of the Republic of Vietnam, the Ngo Dinh Diem government refused to sign the agreement and opened up discussions with the Japanese Embassy in Saigon, claiming a figure US$ 250 million in reparations money. The Japanese considered this “fantastically excessive and absolutely unjustified.” As related by Ambassador Konagaya to F.J. Blakeney, an Australian Legation official, Japan claimed that its army had not engaged in fighting in Vietnam and very little damage was incurred. Accordingly, only Japanese damage could be taken into account. However, as the Diem government reportedly countered, Vietnam should be compensated for the losses suffered on account of the war affecting production generally, including industrial, mineral, etc. But the major part of the Vietnamese claim was that, at the end of the war, the Japanese army sequestered enormous quantities of rice from the north and south, with the apparent intention of building up large stocks in the mountains to enable it to continue fighting whether or not the Emperor surrendered, and that this requisitioning led to disastrous famine in the north and the death of some one million Vietnamese. In reply, Konagaya asserted that, apart from the figure of one million, Vietnam had not provided statistics to support its claims for these immense reparations, and “that, in fact, no statistics exist” (Ibid, and See Gunn 2011).

Following 18 months negotiations in Saigon between Ambassador Konagaya and Foreign Minister Vu Man Mau, the Vietnamese claim was reduced (late December-early January) from US$ 250 million to US$ 200 million. This was still considered too high for Tokyo (apparently Japan started the negotiations with a figure of US$ 8 million, later raised to US$ 50 million). Meantime, as the Australian Legation commented upon this reported conversation, “the reparation agreements question is bedeviling Vietnam-Japan relations.” It also blocked trade negotiations (Ibid).

Blakeney also signaled President Ngo Dinh Diem’s thoroughgoing dislike and distrust of Japan. As he reported, Diem was unwilling to agree to a procedure under which, once an overall figure had been settled, Japan would pay in a variety of goods (both consumer and capital). Reportedly, Diem argued that small projects and special payments continued over an extended period of time was “a classic method of capturing the Vietnamese market.” Instead, he insisted that Japan pay for a few major projects, namely building one of the dams in the southern plateau (Ibid.). This is actually an important revelation and we are left wondering whether Diem was following his head or his American advisers (as discussed below). While Diem’s confrontation with the Japanese over the reparations questions revealed real agency on his part, his willingness to rubber stamp big projects actually fell in nicely with Japan’s preferences and the generalized pattern of Japan’s big ODA infrastructure projects, which continue in Vietnam unto this day.

The Diem Conversation

According to an Australian Embassy memorandum, while President Diem thought that a settlement in the near future was on the cards, his suspicion of Japan for “’sharp practices” in all commercial and economic dealings remained acute. As the report continued, “It will take more than the settlement of the reparations issue to remove his general suspicions and doubts of the Japanese” (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, F.J. Blakeney, Memo No. 1003 Australian Legation, Saigon, 6 Dec. 1957).

According to Blakeney, in a reported conversation with Diem on 29 November 1957, the President outlined the earlier course of Vietnam’s reparation negotiations with Japan. Following the signature of the Franco-Japan reparations agreement of early 1957, Japan had taken the attitude that any Vietnamese reparation claims against Japan should henceforth be made to France (from whom Vietnam should get its share) and that Vietnam could bring a case against France in the International Court. The President’s own reactions had been sharp and final. He told the Japanese that their attitude was “insulting” and that, if this attitude persisted, Vietnam would cut off all commerce with Japan. Subsequently, Japan realized that this was no empty threat and that, unlike the governments of most, if not all other Asian countries, the government of Vietnam had the effective capacity to restrict such commerce. In fact, commerce with Japan was currently running at only a few million dollars a year (Ibid.).

The Kishi-Diem Communique

Seeking to up the ante on a speedy resolution of the reparations issue, on 19-21 November 1957 Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke visited Vietnam on a state visit, issuing a joint communique with President Diem which does not appear to have been made public. However, as the usually astute Bernard Fall (1958: 571) reflected upon the Kishi visit, for the Japanese, the Vietnamese demands were in the realm of fantasy while, on the Vietnamese side, Japan represented the sole means of procuring capital outside of the US and France. In the event, neither Diem nor Kishi changed their negotiating positions. Kishi himself had been Minister of Commerce and Industry from 1941 under General Tojo Hideki to Japan’s surrender in 1945. Until 1948, he had been imprisoned as a “Class A” war crime suspect, albeit never indicted or tried by the IMTFE. Kishi also had overseen the reparations settlement with Indonesia under Sukarno between 1951 and 1958 (Nishihara 1976).

Upon Prime Minister Kishi’s arrival in Saigon, President Diem informed him that Vietnam wished to have good relations with Japan, the more so since the two countries shared Asian cultures. He had put the case that it was in Japan’s own interests to settle the reparations problem with Vietnam as soon as possible since, until this was done, there could be no normal commercial relations between the two countries, that this was at odds with Japan’s own interests, and that in the space of a few years of normal commercial relations, Japan could expect to gain in terms of trade much more than the amount of reparations being sought (F.J. Blakeney memo op,cit).

As Diem reportedly explained to Kishi, Vietnam was not asking for “war reparations” properly so-called, but compensation for “paiements de bouche,” or rice eaten by the Japanese during the occupation of his country, as well as for forcing the French to print something like one milliard piaster of paper money to meet occupation costs, thereby devaluing the currency. If Japan did not pay the whole sum, currently claimed, he argued, then it should pay a portion. According to Blakeney, “In answer to my query, the President confirmed that the figure the Japanese were now considering was something in the region of US$ 85 million. Asked whether this was in cash or services or a combination of both, he replied that Vietnam has signaled several large projects such as Da Nhim. I gathered that [Special Envoy] Uemura’s negotiations here later this month will be concerned with this figure” (Ibid).

The Wolf Ladejinsky Conversation: Diem’s Attitude towards Japan

According to an Australian Legation report, Diem’s opinionated American adviser, the Ukranian-born Wolf Ladejinsky, who had earlier played a major role in land reform in Japan under SCAP, quoted the President as saying that the Japanese are a nation without spiritual values, and that we cannot trust them. He also attributed the triumph of communism in China to Japan’s pre-war record in China. He did not think that defeat had changed Japan’s ways or that Japan had given up on its “co-prosperity sphere.” Reportedly, he stated that, the 20 Japanese technicians who sought admission to Vietnam equaled 20 Japanese spies. Diem apparently favored Western advisers (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, Australian Legation, Saigon, savingsgram, 1 Oct. 1956). America’s lead man on land reform under Diem, Ladejinsky’s thoughts on communism are of all the more interest, especially as his career barely survived a McCarthyist era probe just prior to his Vietnam appointment (1955-61).

Ladejinsky also prepared a paper for Diem on reparation negotiations. Having examined Japanese (reparation) agreements concluded with Burma and Thailand, he acknowledged that both negotiated from weakness, having had large rice surpluses to dispose of for urgently needed Japanese goods. Ladejinsky thus advised Diem that Vietnam’s bargaining position was stronger. Unlike Burma, Vietnam had large US financial and economic aid to bolster the economy. He also showed how the Thai were “miserably tricked” by the Japanese through out-and-out misrepresentation. He was also of the opinion that the Japanese had not succeeded in being accepted as trustworthy and their vanity in this regard should be played upon as much as their claims for expanded trade relations (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, G.J. Price, secretary, Australian Legation, Saigon, 30 Aug. 1956). Diem would be less receptive to American advice in pushing through land reform and, of course, would demonstrate himself as intractable to American interests in general (See Fitzgerald 1972: 120-1).

In any case, Ladejinsky urged caution in dealing with Japan, citing the experience two years prior of Prince Wan Waithayakonn, Thai Foreign Minister from 1952-57, who had “burned his fingers badly” in accepting and signing an agreement with the Japanese containing “a cleverly veiled clause which radically altered the nature of the agreement.” Burma, he explained, had a somewhat similar experience (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, F.J. Blakeney, Minister, Australian Legation, Saigon, Memo no. 10003, Saigon, 6 Dec. 1957).

The following year (February 1958), Diem reportedly told Blakeney that it seemed that the Japanese were having second thoughts over figures they had earlier agreed upon (about 40 million dollars in material with expectations of additional sums of about 20-30 million in credits). He saw no sign of early agreements (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, cablegram, Dept External Affairs to Australian Embassy, Washington, “South Vietnam-Japanese Reparations”).

The Japanese Embassy in Saigon: The Ambassador Kubota Conversation

According to incoming Japanese Ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam, Kubota Kanichiro, who arrived in Saigon on 26 July 1958, an agreement with the Republic of Vietnam would be considered as covering the whole country and no negotiations would be needed with the communist regime in Hanoi. In conversations with Australian diplomats, he referred to Japan’s purchases of coal from North Vietnam as indispensable trade for both partners. “I want to stress that trade and politics are two different subjects,” he asserted. “The commercial relationship between Japan and North Vietnam has no political implications. Japan can carry on trade with any country regardless of ideological concepts” (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam “Reparation Agreement with Vietnam,” To Dept of External Affairs, Canberra from Canada Delegation ICSC, Saigon Japanese Reparations, 31 July 1958). We shall return to the separation of politics and economics theme below. Sometimes described as a “tactless nationalist,” Kubota had a background in colonial Korea and Manchuria. He is better known for his statement of October 1953 during high-level talks between Korea and Japan (“not everything that Japan did in Korea was wrong”), setting back normalization talks by four and a half years (Rozman 2011: 104). As mentioned below, Kubota would also be a co-signatory of the Reparations Treaty signed in Saigon on 13 May 1959.

The Japanese Socialist Party Reaction

Japan’s body politic of the time was riven between alliance supporters (the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the political opposition, including the Japanese Socialist Party (JSP), the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), and large sections of civil society, from unions and students, to a largely critical mass media. There was also of course a spectrum of positions on the various issues involved, from the validity of the US-Japan Security Treaty, the role of US bases in Japan, to anti-war opposition, to support to North Vietnam and the reparation question. Even so as, Faure and Schwab (2008: 39) point out, both the left and right in Japan strongly objected to offering compensation to Vietnam on the grounds that very little war damage had been sustained in that country. If so, then it would be even more reason for indignation upon the part of the French (who gave up the demand for practical reasons) and even more so for Diem who could hardly risk losing the moral high ground on the reparations issue to his communist adversaries in the North.

Pending ratification by the Diet, the JSP vigorously opposed the reparation deal. As the JSP argued, first, that Japan had already made substantial indemnity payments to France on behalf of the Associated States of Indochina (Yen 1,650,000,000 plus 33 tonnes of gold ingots according to an undated Mainichi source); second, in the background of the reparation talks stood Nippon Koei KK and other business groups connected with Uemura Kogoro; third, Vietnam was divided and, if later unified, Japan might be obliged to pay North Vietnam; fourth, the north suffered more war damage than the south; fifth, Laos and Cambodia waived reparation payments, so it is would be unjust to give payment to Vietnam; and sixth, the North Vietnamese may retaliate by suspending trade relations and they are the more reliable trade partner (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam “Reparation Agreement with Vietnam,” Keith Brenner, councilor, Australian Embassy, Tokyo, 14 May 1959, File 6/2/3/6/1 memo 450, 14 May 1959). All of these were cogent arguments against rewarding Diem alone, but we have no other evidence of gold and other transfers from Japan to France.

According to Corcoran (a US source), the Japanese Government had made it known that, because of JCP opposition in the Diet to the conclusion of a Reparations Agreement with Vietnam, the government felt it inopportune at the present (to push the settlement) (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, Australian Embassy, Washington, 24 Mar. 1958). As Shiraishi (1990: 18) clarifies, notwithstanding the opposition, the majority LDP under Prime Minister Kishi decided to discontinue deliberations in the Committee on Foreign Affairs and forced through a vote in the general assembly of the House of Representatives at dawn on 27 November 1959, while opposition parties refused to attend. In so ratifying the reparations agreement with Vietnam, Kishi ignored both international and domestic opinion.

As reported in Saigon-Moi (New Saigon) of 3 December 1959, “The Viet Cong put up an anti-reparation demonstration in Hanoi but, on the very same day, the Lower House of the Japanese Diet ratified the reparations Treaty.” On 26-27 November 1959, after an all night session, the Diet Lower House approved the Japan-Vietnam reparations agreement (198 votes in favor versus 131 against). (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam “Reparation Agreement with Viet Nam”).

Role of Associations and Lobbies

The role of associations and lobbies can never be underestimated in discussions on postwar Japanese business links associated with reparation agreements with former occupied countries. The role of the “Jakarta lobby” in facilitating Kishi’s reparations settlement with Indonesia is better studied (Nishihara 1976), but the Japan-Vietnam Friendship Society merits attention. Inaugurated with a ceremony held at the Tokyo Gas Company Hall at Nihonbashi, those present included Tsukamoto Tsuyoshi, former Japanese minister in Indochina. Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru, whose wartime role is well documented, made a congratulatory speech (NAA A1838 3014/11/89 Part I Vietnam Foreign Policy Relations with Japan).

As announced, Japan would subsequently send a delegate to Vietnam led by special envoy Uemura Kogoro to resume negotiations on reparations to seek an early settlement. But, according to a press report, the pro-Hanoi Japan-Vietnam Trade Association urged Japan to suspend negotiations with South Vietnam until south and north Vietnam became united (Associated Press, 9 October 1958). The French Embassy also reported that the DRV communicated via its Trade Association that it would suspend the opening of credits for Japanese imports if Japan continued its negotiations. The Australian Legation wondered whether this was a propaganda gesture (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, “Japanese Reparations,” Blakeney, Saigon Legation, File 221/5/5 13 Oct. 1958). The Japanese public hardly engaged the reparation issue at this juncture, especially given the semi-secret nature of discussions involving privileged tiers of the business, government and bureaucratic world. As mentioned below, it would be the American use of Okinawa bases for bombing of Hanoi that would eventually lead to a rare polarization between state and civil society over all questions touching upon Vietnam.

The Reparations Agreement of 13 May 1959

Signed on 13 May 1959, the war reparations agreement came into effect on 12 June 1960, in line with the Japan-South Vietnam Agreement of January 1960. Of the Southeast Asian countries occupied by Japan, Vietnam was the last recipient of reparations. As the Times newspaper of London (13 May 1959) summarized, negotiations had been delayed for years owing to the “peculiar” international status of Vietnam. When Japan ratified the San Francisco Treaty with Vietnam, the country was under Bao Dai. However, in 1954, as a result of the Geneva Agreements, Vietnam was partitioned at the 17th parallel, and Japan became one of the last countries to recognize Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) as an independent state. The JSP argued that the reparations deal would violate the Geneva Accords. The same argument was used by the DRV which threatened to suspend exports of anthracite coal to Japan. Negotiations resumed in 1957 with the Uemura mission to Saigon. These negotiations broke down over the amount of compensation and Japan’s demand for a most favored nation clause. The agreement, as signed, thus represented a compromise. The amount was about half that demanded by Vietnam, while Japan waived its claim to most favored nation status (tacitly admitting the special economic status of France and the United States).

In attendance, at the signing ceremony in Saigon on 13 May were Vo Man Mau, the Vietnamese Minister of Foreign Affairs along with the Vietnamese ambassador to Japan, Kubota Kanichiro, and secretary general of the Ministry. On the Japanese side, the reparations agreement was signed by Foreign Minister Fujiyama Aichiro, Kubota Kanichiro, Ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam, and Uemura Kogoro (Counselor of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) Japanese plenipotentiary (and a leader of Keidanren (Federation of Economic Organizations) who had pushed the Da Nhim project). President Diem received the Japanese Foreign Minister. As the Australian Embassy interpreted, for the Vietnamese, the signing of the agreements represented Japanese recognition of the Republic of Viet Nam as the legitimate government for the whole of Vietnam. This was deemed a “brilliant diplomatic success” for South Vietnam on the part of Foreign Minister Vo Van Mau) (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam “Reparation Agreement with Vietnam,” Australian Embassy, Saigon, 18 May 1959).

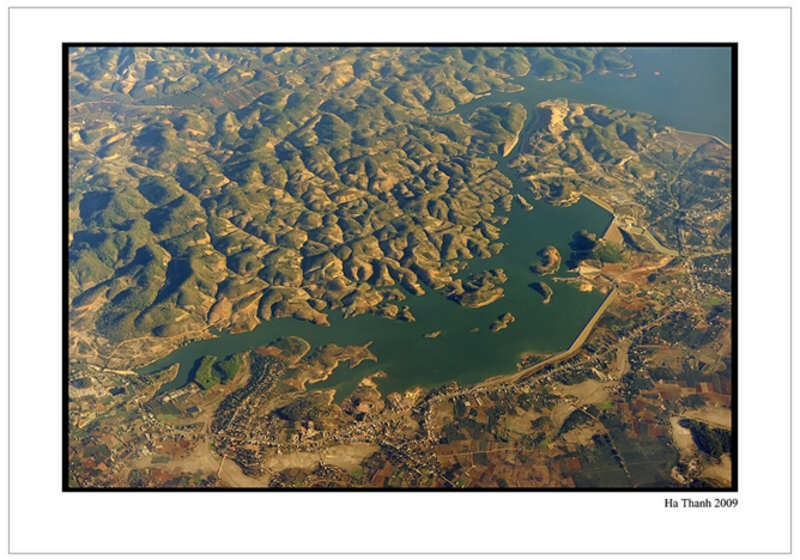

|

Aerial photo of Da Nhim dam (Lam Dong province) |

The agreement provided for the payment of reparations amounting to US$ 39,000,000 over a period of five years, payable in three annual installments of US$ 10,000,000, and two of US$ 4,500,000. As prescribed, payments were in the form of goods and services required by Vietnam, to be used for carrying out projects outlined in the annexes to the agreement. The principal projects upon which the reparations payments were to be expended included the construction of a dam in the Da Nhim Valley (US$ 37,000,000), and the setting up of an industrial center (US$ 2,000,000). Also described as a water conservation project, the Da Nhim Valley hydropower plant located 20 miles east of Dalat, was expected to provide a general capacity of 450,000 kw (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam “Reparation Agreement with Vietnam,” Keith Brenner, councilor, Australian Embassy, Tokyo, 14 May 1959 Reparation Agreement with Viet Nam, File 6/2/3/6/1 memo 450, 14 May 1959). In an exchange of notes between the two sides (Saigon, 13 May 1958), it was also specified that all services supplied would be by Japanese nationals or groups (See this link). This was a propitious start to what would emerge as a prestigious project, one that still plays a part in hydraulic control of the Da Nhim Valley.3

|

Da Nhim flood control gate |

The reparation agreement was accompanied by agreements providing for two Japanese loans to Vietnam, and a joint communique foreshadowing the early conclusion of a treaty of commerce and navigation (See Japan Times, 13 May 1959). Of the two loan agreements, one for US$ 7,500,000 was to be made by the Japan Export Import Bank over a period of three years. The credits were intended to meet the cost of providing materials required in the initial stages of the Da Nhim Valley power station project. In the first year, US$ 2,500,000 would be payable, the balance determined by the two governments. The second was a commercial loan of US$ 9,100,000 mostly allocated to finance a urea plant. However, the amount of reparations and economic assistance to be expended by Japan (US$ 55.6 million) had been settled in May 1958. The main obstacles to progress had been the Japanese request for an undertaking by Vietnam to give Japan most favored nation treatment. But having backed down, Japan then conceded to Vietnam that it was a matter to be dealt with in a treaty of commerce and navigation. As the Australian report interpreted, this was a victory for Vietnam because Japan could no longer link the issue with reparations as a lever (“Reparation Agreement with Vietnam,” op.cit.). Implementation of a second loan ($9.1 million), however, was delayed and finally canceled (Shiraishi 1990: 19).

The fourth country with which Japan had concluded reparation and economic cooperation agreements (fulfilling obligations imposed under Article 14 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty), following Burma, the Philippines, and Indonesia, Japan also signed economic and technical cooperation agreements with Laos and Cambodia, both of which waived reparation claims against Japan. The agreement signed with Laos in October 1958 called for granting economic and technical assistance amounting to US$ 2.8 million over a 2-year period. The agreement with Cambodia signed in March 1959 called for assistance amounting to US$ 4.2 million, spread over three years (“Reparation Agreement with Vietnam,” op.cit.).

Continuing Japanese Aid to South Vietnam

Japanese aid to South Vietnam also received a push from Washington, which directly requested such economic support as it looked to shoring up the Southeast Asian “dominoes.” On 12 May 1964, Foreign Minister Ohira Masayoshi announced in the Diet that, in response to a request of 27 April by US Secretary of State Dean Rusk via a personal letter to Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato, Japan would provide help of a non-military kind to South Vietnam. As the Rusk letter stressed, Japan, with other non-communist countries, should cooperate in helping South Vietnamese to resist communist insurgency. As the Australian Embassy observed, press comments on Ohira’s statements were “consistently cynical, if not hostile.” The JSP also attacked the government’s policy. “Why should the Japanese, they ask, rescue the Americas from the impossible situation into which they have got themselves, and what recognizable impact will Japanese aid have on South Vietnam?” (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, P.F. Peters (1st Sec.), “Japanese Aid to South Vietnam, Australian Embassy, 15 May 1964).

Taking office in November 1964, Prime Minister Sato Eisaku, not only continued the seikei bunri policy of his predecessors, but also played the Okinawa reversion card. Even so, as Havens (1987: 23) wrote in his major study of these years, in exchange for American flexibility over Okinawa (and China), “Sato now seemed to be marching jowl to jowl with [President] Johnson on the war.” It could have been, as Havens suggests, that Sato backed the war without much enthusiasm in the interests of “trade and autonomy,” but it is also true that his attempts at arranging a settlement (missions to Saigon) were largely derided by the opposition as a sop to domestic politics. Despite his “hesitation,” Japan was nevertheless drawn by degrees into more active support as the war widened (Havens 1987: 27).

As Faure and Schwab (2008: 43-7) note, just as revelations emerged in early 1965 that US bases on Okinawa were being used to mount bombing missions over Vietnam, public indignation rose in Japan. Notably, the mass civil society anti-war movement, Beheiren (Betonamu ni Heiwa o Shimin Rengo) or Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam was launched from a coalition of several hundred anti-Vietnam war groups (See Havens 1987: 54-76). Unquestionably the leftist dimensions of this civil unrest shook the business and political elite to its foundations. Emblematic of the polarization besetting Japanese society in these years was not only the rise of Beheiren and the Zenkyoto radical student movement on university campuses (Nichidai), but the reaction from the political and financial establishment. Gerald Curtis (1975) is one who doubted the omnipotence of the zaikai in political circles in those years. He notes, however, that “vulgar” accounts (his language) highlight the existence of various kai or groups linking such top business and political leaders, as with Keidanren president Uemura Kogoro (sometimes referred to as the “prime minister of zaikai”), and former prime ministers Tanaka Kakuei, Fukuda Takeo, and Nakasone Yasuhiro (see this link).

It must have galled American officials that “not a single major daily supported the bombing strategy.” Faure and Schwab (2008: 43-7) nevertheless point out that “Japan’s contribution to America’s war effort was not inconsiderable.” Among other areas of solidarity and active support, US bases in Japan were used for training marines headed to Vietnam, Japanese sailors were embedded on US ships, senior Japan Self Defense Force (SDF) personnel were dispatched as observers to Vietnam and, for the first time, the war was the occasion of the first joint US-SDF military exercises. More than that, the “Vietnam War” provided the backdrop to Japan’s postwar rearmament.

Completion of Reparations Payments

Finally, in January 1965, in line with the Japan-South Vietnam Agreement of January 1960 under which Japan agreed to complete the war indemnification project over five years, the Japanese government announced the completion of its war reparations payments to South Vietnam, totaling US$ 39,000,000. Some 90 percent of reparations of US$ 35 million were used for the construction of the Da Nhim River project, completed on 15 January 1964. The other 10 percent was used for the construction of a cardboard plant, a ship salvage works, a diesel engine plant, a plywood mill, and an iron foundry (UPI, Tokyo, 13 January 1965).

Altogether, some 500 Japanese technicians had been engaged in the Da Nhim project, including the erection of transmission lines from Thu Duc Bien Hoa, a project financed by a Japanese loan of US$ 7.5 million. Under the Colombo Plan of 1954, Japan supplied experts and training at a cost of US$ 600,000 (half of which was diverted to training 200 Vietnamese in Japan). Engineering aid given since 1964 amounting to US$ 1,700,000 included 25 ambulances, medicines and medical equipment, 20,000 transistor radios, blankets and construction materials. Japan supplied medical staff at the Saigon and Cho Ray hospitals, was then constructing the My Thuan bridge on the Mekong River near Vinh Long, and had undertaken a major irrigation project in Ninh Thuch province (US$ 9.1 million). (NAA A1838 3014/11/89 Part 2 Vietnam Foreign Relations with Japan Part II, “Viet Nam: Japan-Australia Consultations Draft memo, Australian Embassy, Tokyo, 12 Jan. 1967).

In this period, according to an Australian Embassy report, Japan maintained a “relatively large and active embassy in Saigon” where there was a small Japanese community dating back to 1940-45. However, in a passing allusion to the contradictory nature of foreign aid in the form of loans, the Australian Embassy reported that the cost of servicing Japanese loans to South Vietnam (almost US$ 1 million in 1965) was more than South Vietnam received in grant aid (US$ 316,000 in 1965) (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, Japanese Interest in Vietnam, Australian Embassy, 27 Dec. 1968).

Doubtless Japanese loans were also tied to the procurement of Japanese goods and services along with commodities. By this stage, as mentioned below, Japan had become an increasingly important source for the procurement of military supplies for Vietnam and, otherwise, Japan had given useful public support to the Allied position in Vietnam. Space precludes an analysis of the kind of capitalist market economy that the Saigon regime was then building in the Mekong delta in what can only be described as a war for control over rice with the burgeoning Viet Cong (See, for example, Selden 1971). While Ladejinsky and his fellows in USAID were aware of the plight of landless peasants in the countryside, Diem was recalcitrant in propping up the big landlords, many removed to the cities and even Paris. Assassinated on 2 November 1963 in the throes of a CIA-backed military coup d’état, Diem would not live to see the opening of the Da Nhim dam two months later. Nevertheless, Washington, and Tokyo did not slacken their support for the military junta which took power in South Vietnam.

However, disaster also struck Da Nhim in 1967. Three years after completion, the Da Nhim hydro plant was badly damaged by the Viet Cong, whose attacks on electric transmission equipment had become frequent since May 1965, just as Diem had early carried the war against the communist enemy to the Mekong Delta with wasting assaults upon the religious sects. In 1969, Japan pledged another US$3 million to rehabilitate one of the damaged penstocks and with an additional US$ 3 million pledged for the construction of a transmission line to Saigon the following year. Total rehabilitation cost was US$ 10 million (NAA A1838 759/3/2 Part I, Japan-Economic Relations with Vietnam, Japanese Interest in Vietnam Australian Embassy, 27 Dec. 1968).

North Vietnam-Japan

According to a Hanoi report of 10 May 1959, the Vietnamese foreign ministry declared null and void any agreement signed between the Kishi Government and the Diem authorities on Japanese reparations to Vietnam. As stated, the Japanese government had to bear full responsibility for the consequences of the decision “running counter to international law,” and the DRV “reserved the right to demand war reparations for Vietnam from the Japanese government.” The statement noted that the agreement was strongly opposed by many Japanese political parties, the JCP, the JSP, along with many progressive personalities. “This is an unfriendly action towards the DRV, it damages the interests of both the Japanese and Vietnamese people.” As the statement added, “the payment of war indemnation (sic) to the SV authorities would only benefit the Japanese monopoly capitalists and serve the scheme of the imperialists to sabotage the Geneva Agreement on Vietnam” (NAA A 1838 3014/11/89 Part II, Foreign Affairs, Canberra, 10 June 1959, “Vietnam’s non-recognition of Kishi-Ngo Dinh Diem agreement”).