Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro – Confronting Images of Atomic Bomb Survivors

Yuki Tanaka

Kikujiro’s Lucky Escape from the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima

A video of Fukushima Kikujiro went viral in Japan. Here.

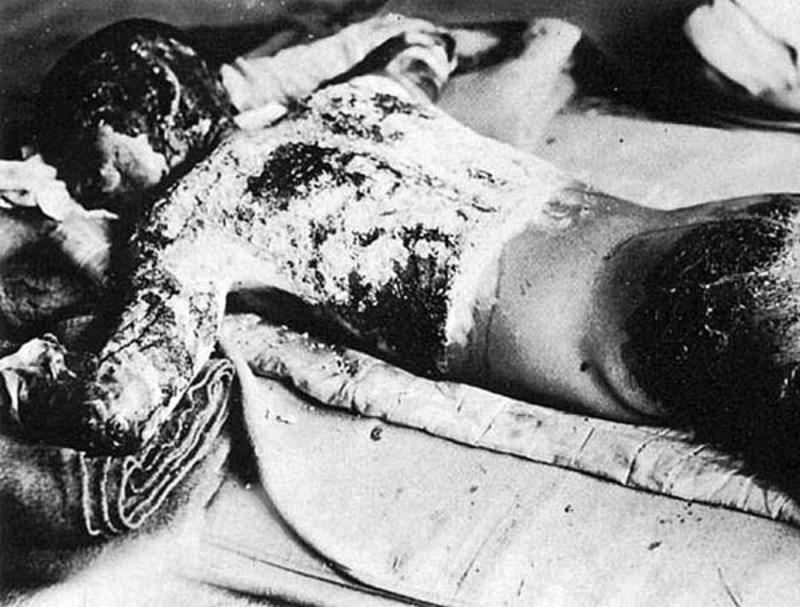

Just before 8:16 am on August 6, 1945, the atomic bomb named Little Boy dropped from the Enola Gay B-29 bomber and exploded 580 meters above Shima Hospital near the Aioi Bridge in the center of Hiroshima City. After the bomb was detonated, powerful heat rays were released for approximately 0.2 to 0.3 seconds, heating the ground to temperatures ranging from 3,000 to 4,000ºC. These heat rays instantly burnt people to ashes and melted bricks and rocks within a 1.5 kilometer radius of the hypocenter. In addition, heat rays burnt buildings, triggered large-scale fires and ignited an enormous firestorm. The blast and fire from the atomic bomb destroyed all 75,000 wooden houses within a 2.5 kilometer radius, leaving only the skeletal remains of a few concrete buildings. In the areas surrounding the hypocenter, people were slammed into walls and crushed to death by collapsing houses. Injuries were sustained from flying glass and other debris even in areas far from the hypocenter. People who survived the blast, many of them severely injured, ran through the flames trying to escape, but many burnt to death.

|

Hiroshima City destroyed by the atomic bomb, August 6, 1945 An A-bomb victim with burns over his entire body, August 7, 1945 |

The fires quickly spread to the outskirts of the city, and firestorms were created at many spots by large and intense fires. Hounded by the flames, people ran into the river in search of a safe refuge. They found little sanctuary, however, as flames licked the surface of the water and soon all six tributaries of the Ota River that ran through the city were filled with dead bodies. Many more went into the river, seeking water to relieve their thirst, but passed away as soon as they reached the water. About half an hour later, it rained hard in the northeast part of the city, quickly bringing down the temperature. As many people were half naked, having had their clothes burnt by the fires, the rain made them shiver with cold. The rain, which contained large quantities of radioactive fallout, was black. To slake their thirst, many people opened their mouths to catch raindrops or licked the puddled rainwater in the street oblivious to the danger of radiation.

The houses between 2.5 and 5 kilometers of the hypocenter were either completely or partially destroyed, and many died trapped under collapsed and burning houses. The injured escaping to the suburbs walked ghost-like with their arms outstretched, skin hanging off, having been melted by the blast. Every place was a hell-like scene. It is estimated that the atomic bombing killed between 70,000 and 80,000 people instantly in Hiroshima on that day. In the following two weeks, 45,000 other died from burns, blast and acute radiation.

On the night of July 30, 1945, i.e., six days before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, together with about 150 soldiers, Fukushima Kikujiro, a 24 year old private, was transferred from the headquarters of the Western 10th Battalion in Hiroshima to the Nichinan Beach of Miyazaki Prefecture on Kyushu Island. His unit was a transport force, but for the last three months he and his fellow soldiers had been training to make suicide attacks against Allied heavy tanks. Each soldier was supposed to dash out of a foxhole carrying a depth charge on his back, and race to the caterpillar of a moving enemy tank to destroy it. Another attack method was to use a long bamboo pole with a depth charge attached to its end. Each soldier would carry the long bamboo pole, run towards the enemy tank and throw it into the loophole of the tank. Both methods were utterly hopeless tactics to stop the expected invasion forces.

During the journey from Hiroshima to the Miyazaki seacoast, the train stopped many times because of frequent air-raid warnings. Each time the soldiers disembarked and hid in the nearby wood. When they finally reached the destination, they were ordered to dig foxholes ten meters apart along the beach. They were to stay in their foxholes and keep watching the sea day and night, with a depth charge on their backs as well as two hand grenades hanging from their waists at all times. They were not allowed to come out. Small rice balls and water in bamboo containers were supplied every day, and each soldier had to make a small hole in his own foxhole for toileting. Machine guns were in the pine wood behind the foxholes. They were aimed at the soldiers in case any attempted to desert. Kikujiro and his fellow soldiers thought that enemy troops would land in a few days as American fighter planes flew over almost daily strafing the shore. They were ready to die.

On August 6, they were informed that all of the soldiers of the Western 10th Battalion who had remained in Hiroshima had been annihilated by the new-type bomb that the U.S. had dropped on the city. The compound of the Western 10th Corps was located just 500 meters from the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. Of course, at the time, they were unaware of the nature of the bomb or how extensively the city was damaged. This news did not particularly bother Kikujiro and his fellow soldiers who thought that they would also all perish as soon as the Allied troops’ landing commenced. At noon on August 15, they were assembled in front of a radio speaker hanging from a pine tree. It was Emperor Hirohito’s “Imperial Message of the End of the War.” One of the soldiers who jumped for joy was severely beaten by the commander, who drew a sword and shouted at the soldiers to go back immediately to their foxholes and prepare to fight to the death. He threatened to kill anyone who tried to escape. However, the following morning, the commander quickly disappeared after telling them that they would clean up the site and then be dismissed. Perhaps he feared his soldiers would take revenge for the ruthless treatment that he had inflicted upon them. With the commander gone, the soldiers spent several days dumping all the weapons and ammunition in the sea and destroying official documents.

At the end of August, Kikujiro returned home to Shimomatsu, a small fishing town in Yamaguchi Prefecture. He was carrying only a blanket and a small quantity of rice in a sock, the last supplies given to each demobilized soldier. Kikujiro’s mother and sister were astonished to discover that he was alive, assuming that he had been killed in Hiroshima by the atomic bomb.

At home Kikujiro was shocked to read a leaflet entitled “The Manual of the National Resistance” issued by the Imperial Headquarters and distributed earlier to households throughout Japan. It said: “Fight your way into the enemy position when they come to land. In hand-to-hand fighting, stab the enemy’s stomach with a bamboo spear, or make a surprise attack from his back with a sickle, knife or hatchet, and kill him. In grappling with him, poke him in the pit of the stomach and kick his testicles hard.” Women, as well as men were equally expected to sacrifice their lives for the Imperial Nation of Japan. Reading this leaflet, Kikkujiro realized how lightly military leaders regarded the lives of women and children and their lack of qualms about sending defenseless citizens to be killed. Kikujiro also learned that while he was away his sister had married a noncommissioned officer on a submarine. The couple spent two days together before he went off. Before Kikujiro returned home, his sister was informed of her husband’s death.

Kikujiro’s Life during the Asia-Pacific War

Kikujiro was a typical rural youth growing up in pre-war Japan. He was deeply influenced by emperor nationalism during adolescence. He was 10 years old in 1931when the Japanese Army used the pretext of an explosion to seize Manchuria and establish Manchukuo under Japanese aegis. This was the start of the Asia-Pacific War, which Japan fought continuously for the next 15 years, extending the battlefield from Manchuria to China to Southeast Asia and the Pacific. From that time on school children were more and more influenced by Imperial militarism and contempt for Chinese, Koreans and other Asians. When Kikujiro graduated from elementary school, two of his classmates volunteered for military service and were sent to Manchuria. In those days, children who completed the 9 year elementary school at the age of 15 were eligible to “volunteer for military service.” Both classmates were killed in action at age 17. Kikujiro thought that it would be a great honor to die for the emperor like these classmates if he could kill at least 50 Chinese “bandits” before he died.

Therefore, it was natural for him to think of serving in military as soon as possible. However, because his father died when he was two years old and his family’s fishing business went bankrupt, when he graduated from elementary school Kikujiro was apprenticed to a local watchmaker in order to support his family. Three years later, he quit the apprenticeship and went to Tokyo hoping to pass the entrance examination for a technical school. He delivered newspapers in the early morning, which allowed him to live in a shop and study during the day. Two years later, however, in April 1941, he was called back home for a health check and physical fitness test required for conscription. Because of his physical weakness, he was not drafted immediately but instead was enrolled in the reserve army. He felt ashamed as many of his old friends were drafted. For the next three years he worked as a watchmaker in his home town. Following escalation of the war after Pearl Harbor, many of his conscripted friends were killed in action. Ashamed and frustrated at being unable to contribute to the war, he often went to the local railway station to participate in the ceremony of receiving the ashes of dead soldiers.

In April 1944, when the war situation in the Pacific turned sharply against Japan, Kikujiro, with many reservists, was finally drafted. He was elated. In October, 1943 all healthy male university and college students studying the Humanities and Social Sciences were subject to the draft. Previously, students were exempt from conscription. In December 1943 the conscription age was reduced to 19 years of age. In 1943, more than one million Japanese men were drafted, and another 410,000 enlisted.

Drafted as a private into the Western 10th Battalion of the 5th Division in Hiroshima, Kikujiro quickly learnt that the rank and file of the Japanese Imperial Army were constantly beaten and ruthlessly bullied by veteran soldiers. Within the first few months of training, a few men unable to endure the cruelty inflicted upon them committed suicide. Kikujiro survived the first few months despite suffering from jaundice. He was not included in the special unit formed from some of the new draftees and sent overseas by ship from Ujina, the main port of Hiroshima. Their ship was sunk by a U.S. submarine shortly after it passed the Bungo Channel between Shikoku and Kyushu heading towardshimomatsus the Pacific Ocean. Most of the men on board were killed.

Four months after being drafted, he was kicked by an army horse while attending to it and was hospitalized for three weeks with fractured ribs and a broken left arm. While in hospital, the majority of his fellow soldiers were transferred to Okinawa where they perished during the Battle of Okinawa between the end of March and the end of June 1945. During the battle, nearly 66,000 of 96,000 Japanese soldiers sent from other parts of Japan died – a death rate of almost 70%. In addition to the deaths of the soldiers, more than 120,000 Okinawan civilians, one of every four Okinawans, died. American casualties were 12,000 dead and 38,000 wounded. Fortuitously, Kikujiro escaped death again.

Although he was released from the hospital after three weeks, on the doctor’s recommendation, he was assigned to clerical work at the Hitachi shipyard in Ube, not far from his home, where submarines were constructed. As he was fond of handling machines, he often volunteered to do manual work in the factory as well. However, in April 1945, when the Battle of Okinawa began, and aerial bombing of Japanese cities intensified, he was drafted again, this time into the Inoue Unit of the Yamaguchi 42nd Regiment. The members of this unit were mainly veterans who had served in China and Southeast Asia. Surprisingly it seems that senior officers of the Inoue Unit, perhaps influenced by the practice of Mao’s Red Army, did not wear their rank badges and rarely inflicted violence upon rank and file soldiers. Indeed, they treated their subordinates quite humanely. Some veteran soldiers of the Inoue Unit openly expressed their opinion that Japan would lose the war soon. One month later, Kikujiro, along with about 30 young soldiers from the Inoue Unit, was suddenly transferred to his old unit in Hiroshima, and mobilized into the suicide attack team mentioned earlier. Yet again, because he was included in this special force, Kikujiro escaped annihilation by the atomic bombing.

Photographing War Orphans and Widows

After the war, Kikujiro resumed life as a watchmaker in his home town. He happily married at the end of 1945 and had three children in the following years. He became a district welfare commissioner, that is, a volunteer social worker, who looked after socially and economically deprived people like war orphans, war widows with children, and old people who had lost sons and daughters during the war. A Ministry of Welfare survey in 1952 placed the number of widows in Japan that year at 1,883,890, 88.4% of them with children under 18 years of age. 70,000 such households were jobless and struggling to survive, and many of the disadvantaged worked as day laborers or peddlers. According to the results of the national survey conducted by the same Ministry in 1948, the number of war orphans was 123,511, of whom only 12,202 were under the care of orphanages. There were only 276 orphanages throughout Japan at the time, 238 of them privately run and just 38 public orphanages. These figures do not capture the real state of war orphans at that time. The Asahi Newspaper that year estimated that there were between 35,000 and 40,000 juvenile vagrants who were not included in the government survey. Many orphans were exploited as “child laborers” at various places throughout Japan, many of them traded by dubious “labor brokers.” With the government’s priority of rehabilitating the economy, social welfare for war victims was neglected for some years.

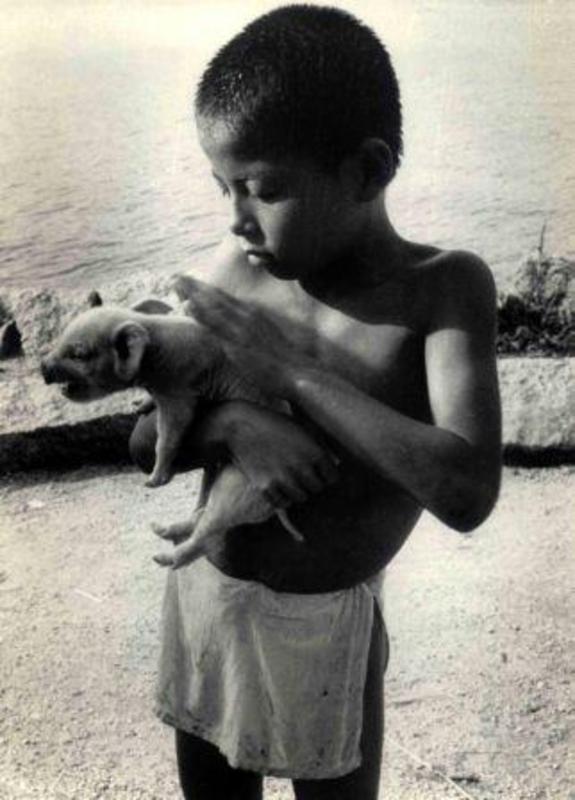

Kikujiro was drawn to looking after orphans because of his personal experience of losing his father in early childhood. He combined volunteer work with his new hobby of photography. His idea was to hold photo exhibitions of war orphans to raise money for the “Kibo no Ie (House of Hope)” orphanage. This orphanage was set up by a former school principal, who returned from Manchuria after the war, and his wife, a former teacher in Manchuria. It was built on a small island, Sen-jima, in Tokuyama Bay, off Tokuyama City (presently Shunan City), about five kilometers away from Kikujiro’s home town, Shimomatsu. Tokushima City was destroyed and 500 of its citizens killed by U.S. fire bombing on May 10, 1945. Many of the 30 children admitted to this orphanage lost their parents in this fire bombing. They ranged in age between 4 and 18. The orphanage relied on the small public funding by the Yamaguchi Prefectural Government as well as private donations, but due to lack of funding, the facilities were extremely poor, and all of the children had to work at the orphanage’s vegetable garden to grow potatoes and other various crops for their own consumption. They were always hungry, and because of their shabby clothes and physical weakness, other children at the local school bullied and discriminated against them. Even teachers ostracized them. Kikujiro visited the orphanage many weekends over two years between 1945 and 1947, and occasionally went to the local school as well, recording the harsh life of the orphans in hundreds of photos. The teacher couple who ran “Kibo no Ie,” were initially reluctant to allow Kikujiro to photograph the children, but they permitted him to do so when he proposed to raise money by exhibiting the photos.

|

A boy cuddling a piglet at the orphanage “Kibo no Ie” |

Through the close contacts he made with orphans at “Kibo no Ie,” he found that one boy’s grandmothers was living in “Kisan-en,” an old people’s home run by a local Buddhist monk in Tokuyama City. In fact, “Kisan-en,” a dilapidated wooden house, was located right next to the temple. Here, about 50 old people, who had no children of their own or close kin to look after them, were literally waiting to die. Many had lost sons and daughters in the war, were stricken with serious illnesses and lacked adequate medical care.

The boy’s grandmother had two sons. Her elder son was drafted into the army during the war. His wife was pregnant at the time. Her second son was drafted into the army soon after. Several months later it was reported that her elder son had died in action. By this time his wife had a baby boy. Shortly after the war, the second son returned home and it was arranged for him to marry his deceased brother’s wife, adopt the boy, and become the head of the family. This was common practice during and immediately after the war. However, the elder son, who had been believed to be dead, was alive and returned home almost a year after the end of the war. Finding that his younger brother was now married to his wife, he left home without saying where he was going after embracing the son he had never seen. His younger brother committed suicide in the hope that his elder brother would come back. The young mother, who lost her husband twice, could not control her grief and hung herself, leaving the young boy in the care of her mother-in-law. The grandmother, who had lost both sons and her daughter-in-law, looked after the boy for a while, but unable to cope with the grief she became ill. Therefore, the boy was sent to the orphanage “Kibo no Ie” and she entered “Kisan-en.” At “Kisan-en,” Kikujiro found many elders who had undergone similarly sad wartime experiences. He started collecting information about their lives and photographing as well.

Through his volunteer work as a district welfare commissioner, he also came to know some war widows with children, who lived in a place called “Tsutsumi-en,” a home for fatherless families, in Tokuyama. Here 73 people from 30 families shared essential facilities like kitchen, toilet and bath. Each family had a tiny room and struggled to survive. Many of these families had lost their houses in the U.S. fire bombing. The mothers were all engaged in heavy work such as day laborers in construction. Many other fatherless families in Tokuyama were on a waiting list, hoping to be accommodated at “Tsutsumi-en.” Families that lost fathers in action during the war were entitled to receive a survivor’s pension. If, however, a father returned home safely from the war and later died from a condition that had developed during his military-service, such as malaria, his family received no pension. There were many such cases in the immediate post-war period. Kikujiro recorded the hard lives of some of the families living in “Tsutsumi-en” in his photos.

In the autumn of 1947, Kikujiro held his first photo exhibition – a traveling exhibition – at several cities in Yamaguchi Prefecture. It was a great success, allowing him to donate some money to the orphanage “Kibo no Ie.” Some of his photos of fatherless families were exhibited in the Nikon Photo Gallery in Ginza, Tokyo, and were praised as profoundly humanistic work by top contemporary photographers such as Domon Ken. Some of the revenue from this exhibition was donated to “Tsutsumi-en.”

Through this amateur photographic work, Kikujiro gradually came to realize the tragic consequences of war for ordinary citizens, and how easily the state—government, militarists and politicians—exploit and sacrifice people for their own political ends. In particular, he realized that Japan’s emperor system ideology made Japan an extremely undemocratic and inhumane nation.

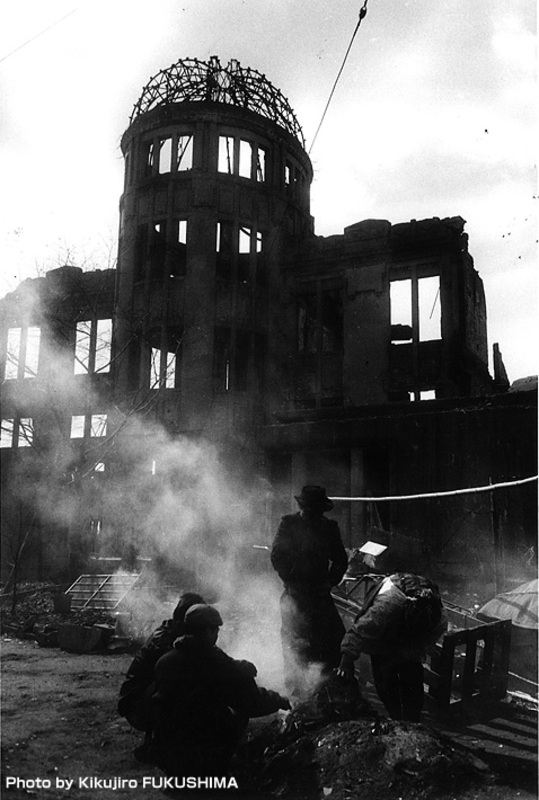

Encountering A-Bomb Survivors

Despite having narrowly escaped the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Kikujiro’s interest in the “hibakusha (A-bomb survivors)” did not develop immediately after the war. Living in Shimomatsu, only a few hours by train to Hiroshima, he visited Hiroshima several times a month to purchase parts and tools for watch-making on the black market. While in Hiroshima, he sometimes walked through the city center, the most seriously damaged part of the city, photographing the ruins of the few remaining buildings such as the A-bomb Dome and the human bones remaining under the rubble. However, given strict U.S. Occupation censorship on publication related to the atomic bombing, Kikujiro took those photos hurriedly, quickly fleeing the site to avoid arrest.

|

Homeless people in front of the A-Bomb Dome in the late 1940s |

On August 6, 1952 he was struck by the fact that he had survived the atomic bombing while fellow soldiers of his own battalion and many Hiroshima citizens were sacrificed. This came to him during the first Memorial Service for A-bomb Victims in Hiroshima. Seeing for the first time the faces of many A-bomb survivors with keloid scars shocked him, and he determined to take photos of survivors from that moment on. At the Memorial Service, he met Nukushina Masayoshi, who had lost his left leg in the atomic bombing. During the war Masayoshi had headed the Neighborhood Association of one of the districts of Hiroshima City, and he felt deeply responsible for the deaths of many residents in his district, having mobilized them to destroy buildings on the morning of the bombing in an order to create a firebreak.

Citizens of Hiroshima were puzzled about why their city had been spared while many other cities were destroyed by U.S. aerial bombing, but they were preparing for attacks by making firebreaks throughout the city. On the morning of August 6, 1945, many local residents as well as high-school children were mobilized for this work and as a result many of them became victims of the atomic bombing. Indeed, Masayoshi was working hard to help the hibakusha, spending his own money to aid those who were impoverished. He was greatly admired for his devotion to these activities. Despite illness, he refused to be hospitalized in order to continue to practice charity. He died in 1965.

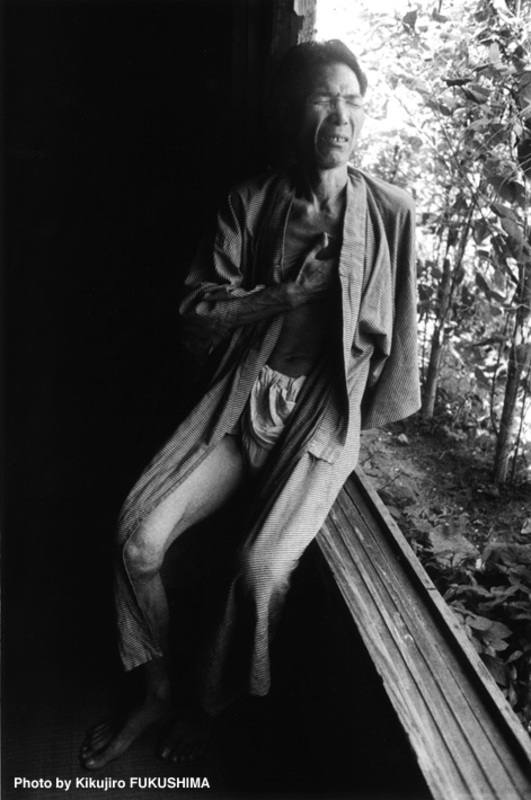

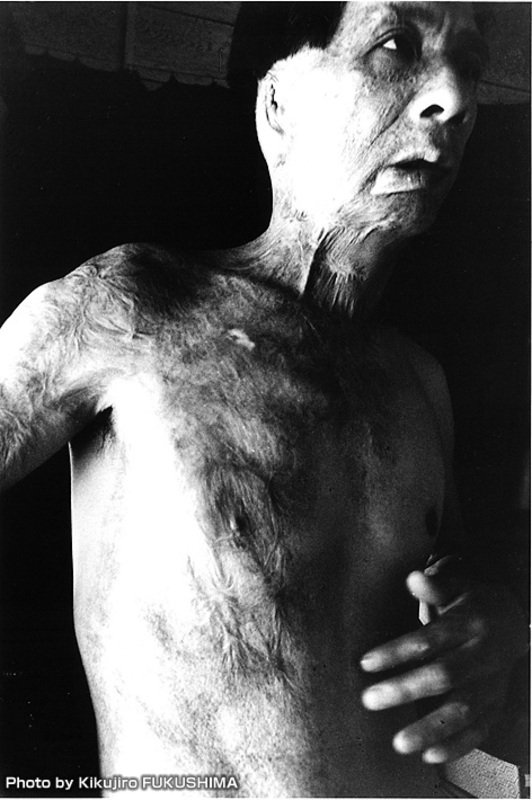

Masayoshi introduced Kikujiro to a few other hibakusha. One of them was Nakamura Sugimatsu. Sugimatsu was among those who were constructing a firebreak 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. Knocked down by the blast, he was buried under a collapsed building, and fainted. However, he regained consciousness when he was surrounded by fire. He madly crawled out the rubble, leaving behind many others crying for help. He could not remember how he returned to his home eight kilometers away. But it was close to evening when he reached home, meaning that he had wandered around the ruined city for hours trying to find his home. As soon as he arrived, he fainted again. Fortunately his house was not damaged, and his pregnant wife, Haruko, and all three children were safe. He regained consciousness, but his whole body was severely burnt. Soon the burnt skin suppurated and became infested with maggots. His hair fell out and he became bald – a symptom typical of radiation sickness. For the following month he hovered between life and death, in and out of consciousness. Every day his wife walked four hours to farmhouses outside the city to get some special herbs that were believed to cure burns. During this difficult time, Haruko gave birth to their fourth child, and miraculously Sugimatsu recovered from the serious illness.

|

Sugimatsu suffering from lethargy sickness at home |

By mid-1947, having gradually regained his health Sugimatsu started working as a fisherman as before. Until then, two of his four children had been raised by his relatives as he had hardly any income to support them. The four children were Mitsuseki (an 8 year old boy), Yoko (a 6 year old girl), Misuzu (a 4 year old girl), and Tsukasa (a 2 year old boy). In 1948, his wife gave birth to another baby girl, Miyoko, and the family looked forward to the return of normalcy.

However, from 1949, Sugimatsu’s health suddenly deteriorated, and because of fatigue, he could not work. Heavy fatigue was a common symptom among many hibakusha in the 1950s and 1960s, and people called it “burabura byo (lethargy sickness).” His wife worked hard to earn money by peddling fish in order to enable Nakamura to see a doctor. The following year, however, she started suffering from anemia. In March, 1951, shortly after giving birth to their sixth child, Sugiko, a daughter, Haruko died of cervical cancer. It was suspected that her cancer was caused by the exposure to radiation when she walked through the radioactive city center every day over several weeks in order to get herbs for Sugimatsu. Sugimatsu did not even have enough money to hold a funeral for Haruko. At the request of the ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission),1 he supplied Haruko’s body for an autopsy at the ABCC, and in return he received 3,000 yen. This allowed him to have a simple funeral. After the funeral, only 180 yen was left. That night he decided to kill his six children by strangling and then commit suicide. With the remaining money, he bought rice and fish and fed the children, and waited until they fell asleep. On seeing their innocent sleeping faces, however, he could not go through with the act. The following night, he tried to commit suicide, but failed again.

In late August 1952 Kikujiro visited Sugimatsu for the first time at his home in Eba at the mouth of the Ota River at the southern end of Hiroshima City near Hiroshima Bay. From mid-1952, shortly after his wife died, Sugimatsu and his children were on welfare provided by the city council. The family’s monthly allowance was 7,815 yen. According to a survey conducted by the Ohara Institute for Social Research of Hosei University, the average income of Japanese households in 1952 was 23,066 yen. Because of the high inflation caused by the Korean War, from 1950 commodity prices soared, and the poorest families, with revenues between 4,000 and 8,000 yen, needed at least 13,045 yen to survive. One can imagine how hard it was for Sugimatsu with six children to survive with 7,815 yen. Sugimatsu’s older children often did not go to school because they had nothing decent to wear when their clothes were being washed. They wandered around the river collecting shell fish or anything else edible, and begging for left-over vegetables at grocery stores.

|

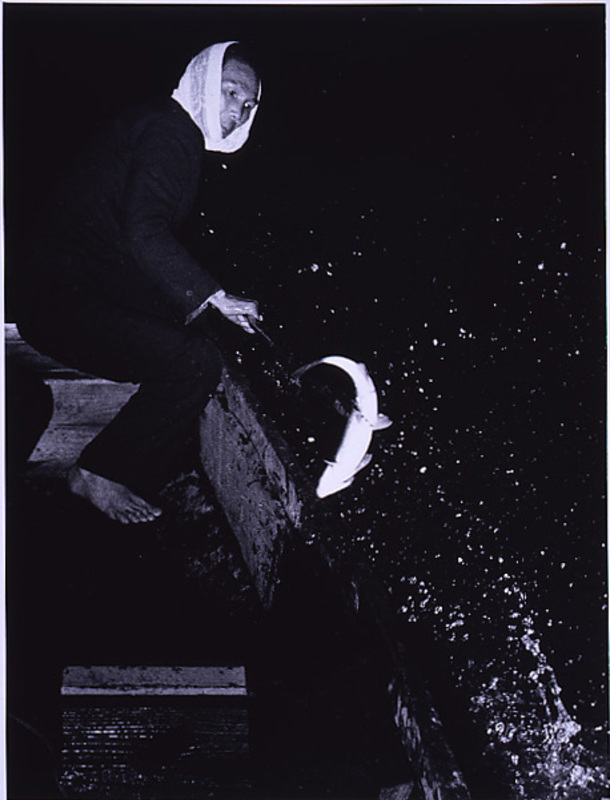

Sugimatsu and his son, Sekimitsu, in a boat going out to fish Sugimatsu catching a fish |

In order to supplement the meager welfare relief allowance, Sugimatsu occasionally went out to fish despite his poor health. Yet, as he was unable to row the boat and fish at the same time by himself, he brought his eldest son, Mitsuseki, then 11 years old. Since Mitsuseki was at school during the day, they always fished at night. Mitsuseki rowed a small boat while Sugimatsu speared the fish – mullet and sea bass – which were attracted to the boat by a gaslight. They usually spent a few hours on the boat and caught 20 or 30 fish, which were worth 500 to 600 yen. Sometimes, Sugimatsu had a fit on the boat and was unable to continue to work. Mitsuseki then frantically rowed back to the landing, carried his father on his back up the riverbank, put him on a cart, and pulled him home. It was an extremely hard task for the 11-year old boy. They earned at most 5,000 yen a month from fishing. It was necessary to sell the fish surreptitiously, because if the city council discovered they were earning money from fishing, the amount they earned would be deducted from their monthly allowance.

|

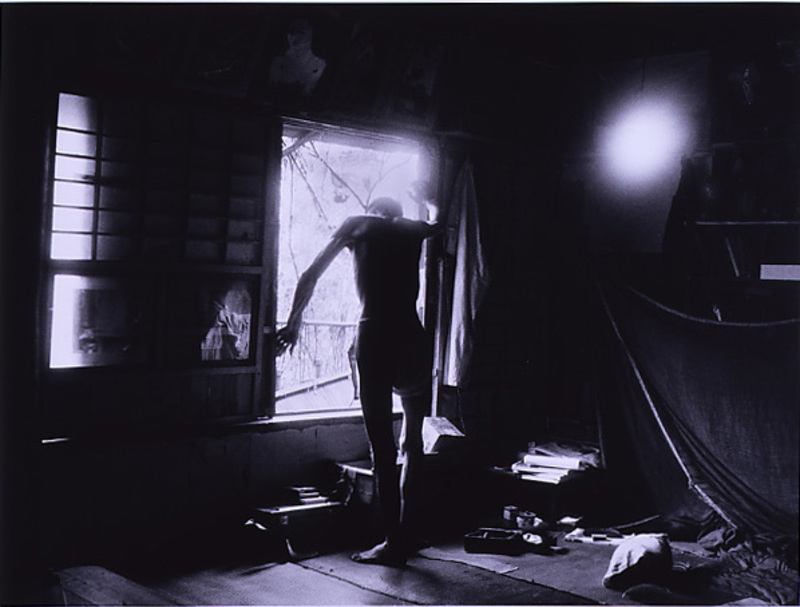

As Sugimatsu suffers a violent fit, one of his daughters runs from the house |

Sugimatsu’s frequent violent fits always started with excruciating stomach pain and shivering and ended with splitting headache and high fever. He would thrash about, crying out “my body is burning and my head is cracking.” No one could help him once it started and he had to be left alone in bed for a few hours. If the children were at home, they usually ran out of the house unable bear to watch their father’s agony and screaming at them.

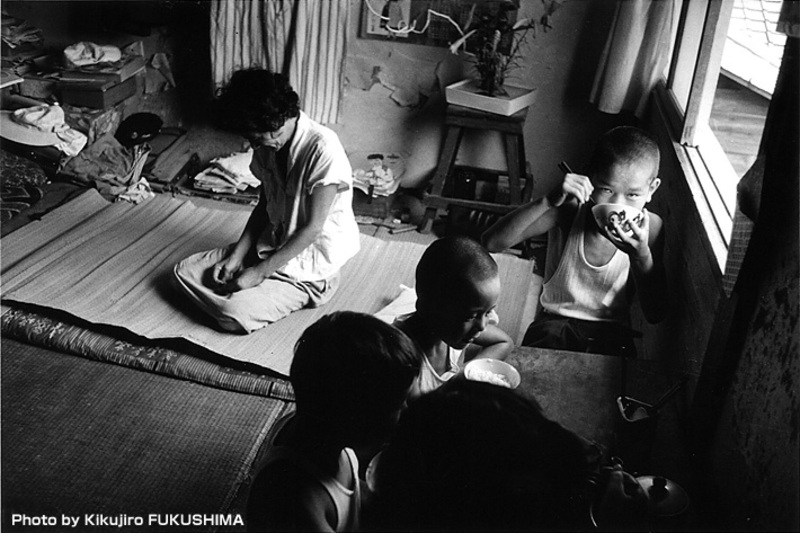

Although Kikujiro continued to visit Sugimatsu once or twice a month, he hardly took any photos of him or his family for the first year or so. Kikujiro did not have the courage to take photos of a man in ill health and in extreme poverty with six children. He clearly understood that the goal of taking documentary photos was to reveal the human dignity of his subjects, yet, he was also acutely aware that it could deeply violate their privacy. In late August 1952, he was visiting a few other hibakusha in Hiroshima and tried to photograph them. One was a hibakusha with three children, who lost her husband because of radiation sickness caused by the bomb. She was also dependent on welfare. She had worked as a day laborer, but due to radiation sickness, could no longer work. She was living in a special accommodation set up for widows with children like “Tsutsumi-en” in Tokushima. One day, Kikujiro took a photo of her three children eating a meager dinner – just rice with no side dishes at all. She herself was not eating, being unable to afford to do so. Kikujiro realized that one child was glaring fiercely at him when he took a photo. The next time he visited, she told him never to return. He realized that he had grossly intruded on the family’s privacy, wounding their dignity. Because of this experience, he became hesitant about asking for permission to take photos of Sugimatsu and his family. Despite his strong desire to use his camera, he contented himself with acting as a volunteer social worker, bringing food and clothing to Sugimatsu’s children and advising him about the welfare system and medical assistance.

|

A hibakusha with her three children at dinner Sugimatsu squatting on his futon (bedding) |

Recording Sugimatsu’s Agony and the Travails of the Nakamura Family

After about a year from Kikujiro’s first visit, Sugimatsu suddenly confronted him and asked him for a favor. He told Kikujiro “Please take revenge for me so I can die in peace.” Kikujiro could not understand Sugimatsu’s words. Sugimatsu explained in tears that he wanted Kikujiro to record his life in detail so that people throughout the world could know how painful the life of the A-bomb survivors was. Kikujiro responded that he would do so, but he needed permission to photograph without regard to the privacy of Sugimatsu or his family. Sugimatsu promptly granted permission. From then on, Kikujiro commuted to Hiroshima every Sunday and over the next eight years, in many moving photographic images, he recorded the anguished life of Sugimatsu and the gradual breakdown of his family.

Until Kikujiro informed him, Sugimatsu was unaware of the availability of medical assistance for people on welfare. In the autumn of 1952 Sugimatsu went to see a local doctor for the first time, utilizing the medical assistance service. Several symptoms were diagnosed: fatigue, dizziness, headache, difficulty breathing, intracranial hypertension (pressure inside the skull that can result from or cause brain injury), stomach and bowel tenderness. Despite this diagnosis, he refused to go through more comprehensive medical examinations for fear that he would be diagnosed with “A-bomb disease” and would have to undergo several operations. He did not think that he had the physical strength to survive major operations, and he knew that many hibakusha had died soon after operations. In fact, the peak time of the deaths of hibakusha was between 1951 and 1952, and at that time, with leukemia prevalent, many were dying with or without operations. Therefore, during the following year, Sugimatsu kept going to a local doctor, receiving only painkilling and nutritional injections.

His condition rapidly deteriorated, and in late 1953 he was hospitalized. The pressure inside his skull was five times higher than normal, and to ease it he received more than 100 spinal punctures – an extremely painful treatment – over the next two years. Doctors were unable to find the cause of this symptom so he went to four hospitals in the next three years. At one time it was suspected that he had a brain tumor, but this was never confirmed. Once he became critically ill when his nose continued to bleed for ten days following a nose operation. He was seen as insane because he had to have cold showers whenever he had a spasm and his body became hot, even in mid winter. He was always discriminated against by other patients and hospital staff who viewed him as a “filthy man” because of his shabby futon (bedding) and worn out, unkempt clothes. In those days each patient brought his or her own bedding as well as clothing to the hospital, and Sugimatsu could not afford clean bedding or new clothes. Finally, after spending three years in four different hospitals, he was sent home as doctors could find neither the cause of his illness nor any effective treatment. The fact that he tried to commit suicide a few times in hospital also made the doctors wary of treating him. As a last resort, he went to the ABCC where he received an extensive examination only to be told that he had no particular illness, and that his symptoms were probably caused by hysteria.

|

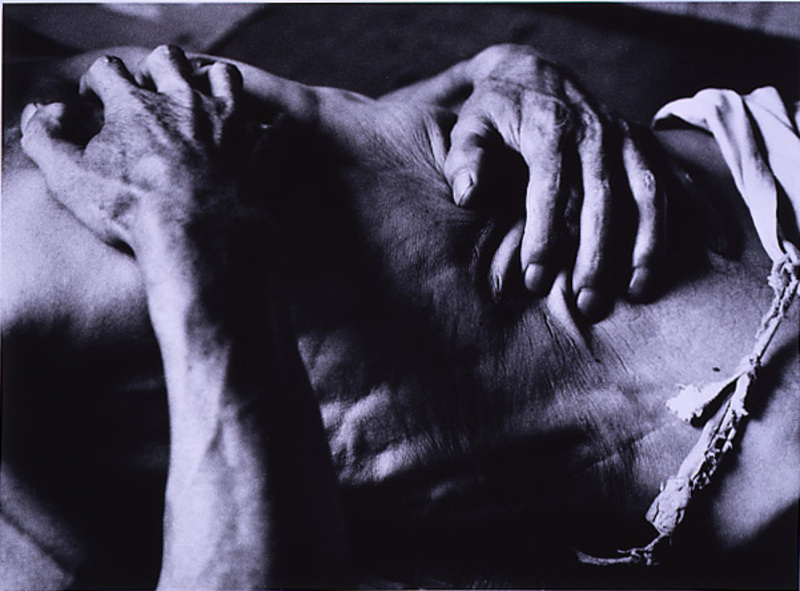

Sugimatsu enduring the pain, scratching a wooden fence |

During the three years that Sugimatsu was hospitalized, his eldest daughter, Yoko, dropped out of junior high school to work at a nearby oyster farm during the day, breaking oyster shells. In the morning and evening, she looked after her brother and three sisters. Yoko received only 3,000 to 4,000 yen a month, but, astonishingly, the social welfare office deducted even this meager sum from the family’s monthly allowance rather than providing financial assistance that would allow the 13 year old to attend school. While Sugimatsu was in hospital, his eldest son, Mitsuseki, graduated from junior high school. He immediately became an apprentice roofer and left home, fleeing the family’s poverty-stricken life. As he was no longer living at home and was earning a salary, the family’s monthly allowance was reduced. This imposed greater responsibility on Yoko to provide for the family. In postwar Japan, it was often mothers and daughters whose labor made possible family survival.

In 1957, Sugimatsu returned home but was unable to work due to his debilitated condition and Yoko continued to support the family. Sugimatsu took to drinking cheap alcohol, making his children’s lives more difficult. Furthermore, because of the doctors’ diagnoses and the ABCC report, welfare workers thought that Sugimatsu was feigning illness in order to receive the welfare allowance, and started writing extremely negative reports about his behavior. This created a vicious circle: Sugimatsu mistrusted the welfare workers and became antagonistic towards them, and in return, they scrutinized Yoko’s meager earnings ever more harshly.

|

Sugimatsu with his four remaining children in 1957 |

In 1958, Sugimatsu’s second daughter graduated from junior high school and became a waitress. Like her elder brother, she also left home and soon started living with her boyfriend, abandoning the family. Tsukasa, Sugimatsu’s fourth child, completed junior high school in 1959, and became a factory worker. He commuted from home, but spent almost his entire salary on his new hobby of raising racing pigeons, hardly contributing to the family’s finances. It seems that he needed a psychological escape from the depressing family atmosphere. In 1961, Miyoko also left home when she finished schooling without informing anyone where she was going. A few months later, Kikujiro encountered Miyoko working as a waitress at a coffee shop in the city, but she pretended not to know him, telling him that she was Asano Sanae, a descendant of the warlord of Hiroshima during the Edo period. As Sugimatsu’s children abandoned home and family one after another, the family’s welfare allowance shrank. A few years later, after her youngest sister finished her schooling, Yoko started working as a nightclub hostess. Although Sugimatsu’s economic condition improved thanks to Yoko’s income, he lost contact with most of his children, so that psychological damage compounded his long-term illness.

|

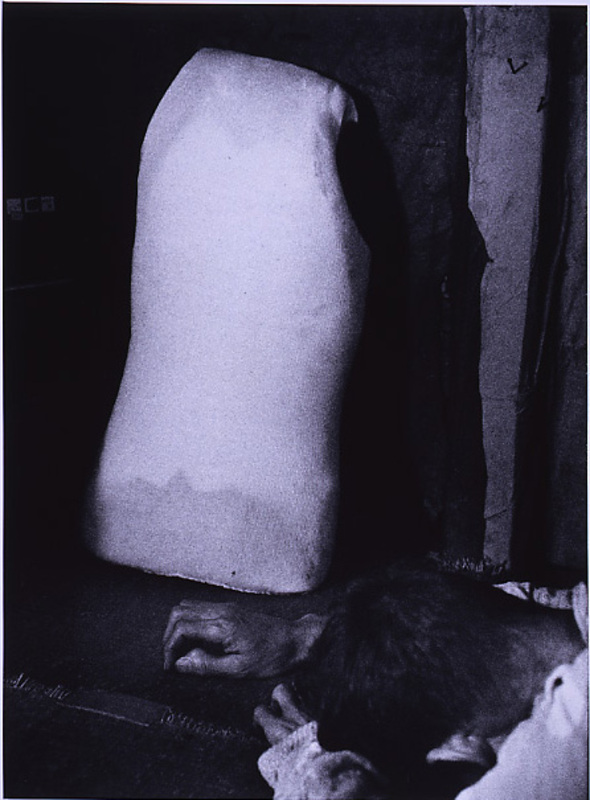

Sugimatsu lying next to a large plaster cast provided by the A-Bomb Hospital |

In September 1956, the A-bomb Hospital was set up at the Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima to treat hibakusha patients. From April 1, 1957, the Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Support Law took effect as a result of persistent lobbying by hibakusha groups. For the first time, hibakusha who were recognized by the Minister of Health, on the recommendation of the A-bomb Survivors’ Medical Examination Board, as having illnesses directly caused by the atomic bombing, became eligible for free medical treatment. The recommendation of the A-bomb Survivors’ Medical Examination Board was made on the basis of a comprehensive medical examination that was conducted twice a year at a hospital designated by the government. In light of the rigid rules compounding the lack of records from the period of chaos that following the bombing, it was difficult for many hibakusha to be officially acknowledged as “A-bomb patients.” Hibakusha groups continued to lobby, demanding that the government amend the law to provide receive free medical service regardless of illness for all hibakusha. In 1960, the government finally amended the law, making the “special hibakusha” eligible for free medical treatment for any type of disease, and providing a 2,000 yen monthly allowance in addition to free medical service for patients whose illnesses were officially acknowledged as resulting from the atomic bombing. The “special hibakusha” meant those who were within 3 kilometers of the hypocenter at the time of the bombing, those who entered the city within 2 kilometers of the hypocenter within three days of the bombing, and those in certain areas of the city which were officially acknowledged as “hot spots,” i.e., areas that were highly radioactive following the bombing. The amended law enabled some 28,000 hibakusha to access full free medical service.

The amended law enabled Sugimatsu to become one of these “special hibakusha” entitled to receive free medical treatment at the A-bomb Hospital. On his 52nd birthday on September 15, 1960, he went into the A-bomb Hospital with hopes that his illness would be cured by doctors specializing in A-bomb disease. Having borrowed money from her employer, Yoko prepared a brand new futon and clean clothes for her father to assure that he would not be discriminated against at the hospital this time. About a month later, however, Sugimatsu was advised to see a psychiatrist and was sent home. The doctors could find no cause for his illness. He received a large plaster cast that extended from his neck to his hip to wear when he experienced a fit. From this day, he lost all hope of recovery. He stayed in bed almost all day long, from time to time doing water color painting – a hobby that he had recently acquired – while in bed. Themes of his paintings ranged from imaginary cityscapes to self-portraits. As time passed, however, the painting became more and more dramatic and darker, and eventually he painted many falling nude women. Seven years later, on January 1, 1967, he died at the age of 59 after a 22 year long bitter struggle with his illness.

Sugimatsu’s physical and psychological suffering compounded by poverty was shared by many A-bomb survivors in the 1950s and 1960s. In this sense, the record of his life is emblematic of the plight of A-bomb survivors in early post-war Japan, a time when little attention was paid to the manifold dimensions of the struggle that victims of radiation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were going through at a time when the entire nation sought to recover from the devastation of the destruction of the cities.

|

Sugimatsu in despair at home |

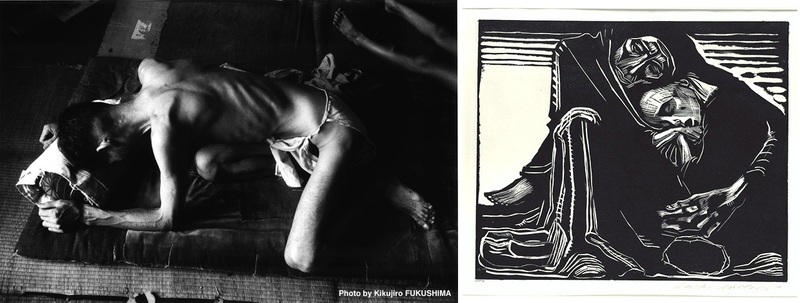

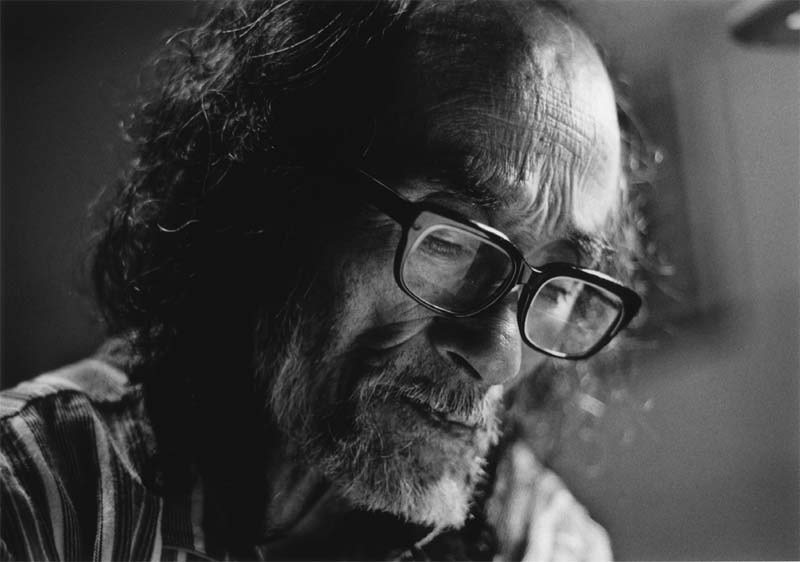

Kikujiro as a Professional Photographer

Kikujiro took literally thousands of photos of Sugimatsu and his family over eight years between 1953 and 1960. He followed Sugimatsu everywhere he went including hospitals and recorded his every movement including his excruciatingly painful fits. He even took photos of Sugimatsu in tears on the tatami as he struggled with pain. Sugimatsu often inflicted self-harm, cutting his thigh repeatedly with a knife, leaving multiple gashes. Kikujiro recorded these gashes, too. The striking impression that these photos leave viewers comes, I believe, from the uncompromising exposure of Sugimatsu’s private physical and psychological agony.

|

Sugimatsu’s tears on the tatami mats Self-inflicted Gashes on Sugimatsu’s thigh Sugimatsu’s foot cramped with pain Student militants in Sanrizuka opposing |

Kikujiro wanted to exhibit some of the photos while Sugimatsu was still alive to fulfill his promise to him. He organized the exhibition “Pika Don (Flash Bang, a popular term conveying the sensation of the bomb): The Record of An A-bomb Survivor” for one week beginning on August 6, Hiroshima Day 1960 at the Fuji Photo Gallery in Ginza, Tokyo. It was a great success and he soon published a book under the same title based on the exhibition. The book was widely reviewed and praised in the Japanese press and he received the “Japan Photo Critics’ Special Award” in 1960.

However, by early 1960, Kikujiro’s watch repair business, long neglected while he photographed Sugimatsu, was on the verge of bankruptcy and he too suffered from depression requiring three months hospitalization. In the hospital, he concluded that he would destroy himself if he continued to photograph A-bomb survivors like Sugimatsu. Yet, as he gradually recovered from depression, he became determined to become a professional photographer. As soon as he was discharged, he asked his wife to divorce him, saying that he wanted to go to Tokyo to work. His wife, however, denied his request, saying that she would run the business so that he could work in Tokyo. All three children chose to live with their father in Tokyo. His first work in Tokyo was the photo exhibition “Pika Don: The Record of An A-Bomb Survivor.” After the exhibition, he commuted between Hiroshima and Tokyo once a month or so, continuing to photograph Sugimatsu and his family.

|

The A-Bomb Slum |

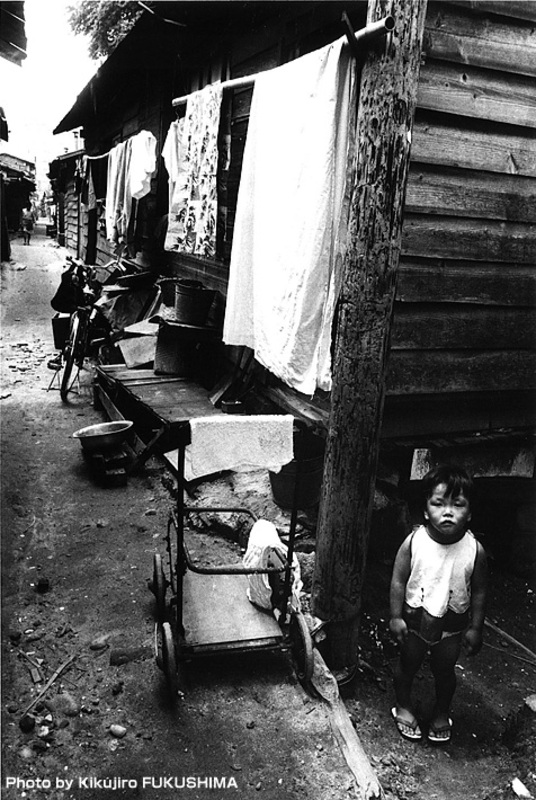

Each time he returned, he also visited the slum area of Motomachi in Hiroshima, where some 1,000 shacks were crowded together on the riverbank stretching over two kilometers along the Ota River. People called it the “A-Bomb Slum” as one third of the 3,000 residents in this area were hibakusha including many Koreans. Most of these hibakusha were day laborers and 240 households were on welfare. All had lost their houses and close kin as a result of the atomic bombing. Kikujiro recorded their lives in the face of extreme poverty, ill health, and social and economic discrimination. Children in the slum were ostracized at school and even some teachers discriminated against them. Some parents organized a cram school in the slum and ran an abacus night class for their children so that they would not be disadvantaged when they applied for jobs after completing school. Korean residents also ran Korean language classes in the evening. As they were occupying the land illegally, the city council and the Hiroshima Prefectural Government ignored their repeated requests to provide water and sewerage. So the residents shared a single well. They produced their own communal fire extinguishers and disinfecting equipment to protect the community—one of many self-help practices that allowed them to survive.

Kikujiro often visited another slum on the other side of the Ota River in Fukushima-cho. This area, 1.7 to 2.5 kilometers east of the hypocenter, was the ghetto of the so-called Buraku people, i.e., untouchables who were regarded by many Japanese as “contaminated.” Many Koreans also lived there. At the time of the atomic bombing, there were about 6,000 residents. The bomb destroyed virtually all the houses and killed 600 people. Four hundred others were missing and presumed dead. In other parts of Hiroshima, school children had been evacuated to the countryside in expectation of U.S. firebombing. But because of deep-rooted discrimination, more than 300 children in the ghetto were not evacuated and became victims of the atomic bomb. Soon after the bombing, Japanese troops were sent to this area. They limited the movements of residents so that most survivors could not escape to the outskirts of the city. The authorities probably anticipated that Burakumin and Koreans might commit crimes, taking advantage of the total confusion at the time. (This reminds us of the fact that many Koreans in Tokyo and Yokohama were slaughtered by Japanese police and civilians following groundless rumors about a Korean uprising shortly after the 1923 earthquake with a 7.9 magnitude struck the Kanto area.) Even those who managed to reach first aid stations were denied treatment when their identity was discovered. As a result some 1,900 people perished within the following year as a result of injuries from burn and blast as well as high radioactivity. The death rate in the year after the bombing among survivors of this ghetto was 33%, 2.5 times that of other areas of the city within 1.5 to 2.5 kilometers of the hypocenter. People in this slum, maintained a strong communal spirit. They collected donations from all over Japan and built their own Cooperative Society Hospital in 1953, three years before the A-Bomb Hospital was established, to look after hibakusha. They even provided free counseling in this hospital. Kikujiro made many friends among these people and also photographed them.

|

A hibakusha in Nagasaki |

Kikujiro traveled repeatedly to Hiroshima while working as a free-lance photographer in Tokyo, commissioned by weekly and monthly magazines to document social and political problems. He was particularly interested in photographing the most disadvantaged people among hibakusha including slum dwellers, young women who could not find marital partners because of keloid scars on their faces, and microcephalic children born physically and mentally handicapped as a result of prenatal irradiation. He also went to Nagasaki, establishing personal relationships with hibakusha before photographing. As in the case of Sugimatsu, he felt that he had to secure complete trust if he was to be allowed to intrude into the privacy of the hibakusha with his camera. Nevertheless, he sometimes failed to grasp the delicate feelings of some hibakusha, at times disturbing them by taking photos without asking permission, believing that he had established mutual trust. Some hibakusha wished never to be photographed, including those who enjoyed close friendship with Kikujiro.

In the 1970s, Kikujiro became acquainted with many activists in Tokyo through recording the activities of student movements against the university authorities and the Japanese government. Among those students was a young boy by the name of Tokuhara Toru, who was a so-called “hibaku-nisei” (2nd generation hibakusha), referring to children born to hibakusha parent(s). His father, Katsu, survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and moved to Tokyo after the war. Kikujiro started visiting Toru and Katsu’s home and recording not only Katsu’s life but also the relationships between Katsu and his three sons including Toru. Kikujiro’s photographic reportage revealed the common fear among hibakusha generations of the effects of radiation on themselves and their descendants and how some eventually overcame the generation gap. Through Toru, he met many young hibaku-nisei, who were involved in political and social welfare movements in Hiroshima in the 1970s and recorded their activities as well.

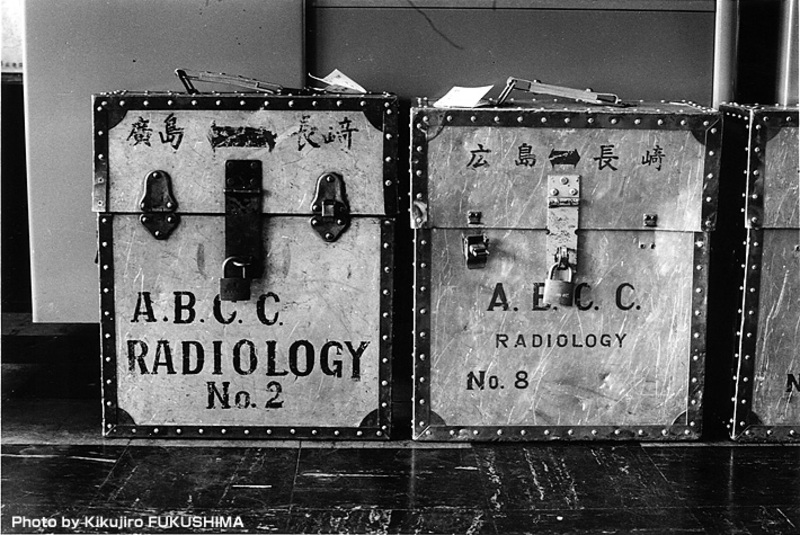

Another remarkable photographic accomplishment of the 1970s was a rare record of the ABCC’s autopsy room, research laboratories and other facilities. In the early 1960s, shortly before becoming a professional photographer, he approached the ABCC and made inquiries about photographining facilities inside the ABCC building atop Hijiyama Hill. Not surprisingly, the request was promptly rejected. Then he asked an editor of Bungei Shunju, a leading nation-wide monthly magazine, to make the same request. He knew this editor well having worked for the magazine. Kikujiro drafted the letter, writing:

‘Many hibakusha in Hiroshima complain that the ABCC uses them as human guinea pigs and provides no medical treatment. However, we think that their misunderstanding may originate from lack of knowledge of radiation sickness and medical science. We would therefore be most grateful if you could allow our photo journalist to visit and interview your staff so that we can inform the people of Hiroshima how seriously you are working to find cures for A-Bomb disease and thus relieve their anxiety.’

|

Photo taken inside the ABCC building |

When the editor received an invitation, Kikujiro was able to visit the ABCC as a Bungei Shunju journalist, and photographed inside the building. Some of these photos are included in his 1978 book Genbaku to Ningen no Kiroku (Records of the A-Bomb and Human beings).

Conclusion

For two decades between 1960 and 1981, in addition to photographing many hibakusha, Kikujiro published numerous photos on student movements, the anti-Vietnam War movement, the Self Defense Forces and Japan’s military industry, pollution problems, environmental issues, Emperor Hirohito, and social welfare issues. He published more than 10 photographic books. In the end, disappointed with Japan’s materialistic lifestyle, he retired at age 62 in 1982, gave up photography, and moved to a small, uninhabited island in the Inland Sea where he made a self-sustaining life for the next seventeen years. Since 2000, he has lived in Yanai, a small city in Yamaguchi Prefecture, not far from Shimomatsu, the home town he lived in until 1960.

His photos convey the profound human feelings of their subjects – pain, anger, fear, sorrow, anxiety, and joy. Unlike other famous Japanese professional photographers such as Domon Ken and Tomatsu Teruaki, who also photographed hibakusha in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Kikujiro never tried to portray these subjects neatly or artistically. Perhaps, this is partly because he was a self-taught photographer who never learnt techniques from professionals. He always tried to capture the expression of his subjects without adding sophisticated technical or artistic embellishment. His work may, therefore, be seen as “crude” and “rough” by professional photographers, yet the “directness” of the images conveys extraordinary power. There is no room there for prevarication. This is particularly so in the case of the photos of Sugimatsu with their uncompromising and direct exposure of human suffering. Kikujiro’s photos of Sugimatsu are strikingly reminiscent of Kathe Kollwitz’s powerful images of war victims.

Kikujiro’s photo of Sugimatsu and Kathe Kollwitz’s print

Whether because of his harsh criticism of the Hiroshima City Council’s treatment of some of the most disadvantaged hibakusha in the 1950s and 1960s, or because his representation of the daily torments of hibakusha life is too unsettling for the authorities and perhaps for some hibakusha, the Atomic Bomb Museum has never acquired Kikujiro’s work on the hibakusha. Perhaps both factors come into play.

|

One of Sugimatsu’s daughters looking at her tormented father Sugimatsu in pain tearing his body with his fingers |

In Hiroshima, the ten years between 1945 and 1955 is often described as the “Blank Decade” because of the lack of information about the lives of hibakusha and their struggles to survive in the devastating post-war economic and social conditions. During the early post-war decades, both hibakusha and non-hibakusha citizens were preoccupied with their own survival and lacked time and resources to record their life activities, either in writing or in photographic images.2 As a result, Kikujiro’s early work in the 1950s and 1960s has immense historical value, particularly his work on the life of Nakamura Sugimatsu, which conveys perhaps better than any other visual record—whether photography or painting—the plight of many hibakusha in post-war Japan.3

It is interesting to note that, through his photographic work, Kikujiro became acutely aware of the tragic consequences that the war brought not only to ordinary Japanese citizens but also to Burakumin as well as Koreans and other Asians. In particular, Kikujiro met many Koreans who had been forcibly removed from their home country to Japanese cities including Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Having been harshly exploited for labor during the war, they became victims of the atomic bombing and suffered not only from various types of illness but also from racial discrimination after the war. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Kikujiro selected topics related to Japan’s war responsibility for his photographic work, in particular Emperor Hirohito including his attitude towards civilian war victims.

It should be noted that one third of young Japanese men who were born between 1920 and 1922 and who comprised the largest segment of the Japanese Imperial Forces, died by the end of the war. Consequently many surviving men came to hold a deep sense of guilt about not having died. This may have made it difficult for them to feel a sense of responsibility for Asian victims of the war. Typical of their attitude, was the determination to work hard to help rebuild Japan on behalf of their deceased friends, i.e., the “true war victims” in their eyes.

|

Self portrait of Kikujiro |

Kikujiro was born in 1921 and belonged to the above-mentioned generation of returned soldiers. However, he acquired a profound sense of universal humanity through his encounter with the extreme inhumanity that the atomic bombing inflicted upon ordinary Japanese and Korean civilians and their postwar plight.

Kikujiro’s life and work teaches us that, to prevent the dehumanization of citizens of any race or nation and thus to reduce acts of violence, it is important that we examine such acts from the viewpoint of the victims. To comprehend the problems of violence through the eyes of the victims means listening to their individual stories, re-experiencing their psychological pain, and internalizing such pain as one’s own. Through his work, Kikujiro spent hours, days and years internalizing the pain of war victims. “Sharing memories” in the true sense becomes possible only through this process of re-living and internalizing the pain of others. Kikujiro’s photographic images capture the essence of “individual stories” of victims. By focusing attention on these individual stories, the scope for “sharing memories” begins to widen, as they lead us to think about fundamental questions of universal humanity.

Yuki Tanaka is Research Professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute, and a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal. He is the author most recently of Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn Young, eds., Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth Century History and of Yuki Tanaka, Tim McCormack and Gerry Simpson, eds., Beyond Victor’s Justice? The Tokyo War Crimes Trial Revisited. His earlier works include Japan’s Comfort Women and Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II.

Recommended citation: Yuki Tanaka, ‘Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro – Confronting Images of Atomic Bomb Survivors,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 43 No 4, October 24, 2011.

Major References:

Pika Don: Aru Genbaku Hisaisha no Kiroku (Flash Bang: The Record of An A-bomb Survivor) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Tokyo Chunichi Shimbun, 1961)

Senjo kara no Hokoku: Sanrizuka 1967 -1977 (A Report from the Battle Field: Sanrizuka 1967 – 1977) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Shakai Hyoron-sha, 1977)

Genbaku to Ningen no Kiroku (The Records of the A-Bomb and Human beings) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Shakai Hyoron-sha, 1978)

Nippon no Sengo o Kangaeru:Ten-no no Shinei-Tai (Thoughts on Post-War Japan: The Emperor’s Bodyguards) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Sanichi Shobo, 1981)

Senso ga Hajimaru (The War Begins) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Shakai Hyoron-sha, 1987)

Hiroshima no Uso (Lies About Hiroshima) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Gendai Jinbun-sha, 2003)

Korosuna Korosareruna (Don’t Kill and Don’t Be Killed) by Fukushima Kikujiro (Gendai Jinbun-sha)

Articles on related subjects

• Robert Jacobs, The Atomic Bomb and Hiroshima on the Silver Screen: Two New Documentaries

• Linda Hoaglund, ANPO: Art X War – In Havoc’s Wake

• Kyoko Selden, Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Messages from Hibakusha: An Introduction

• Ōishi Matashichi and Richard Falk, The Day the Sun Rose in the West. Bikini, the Lucky Dragon and I

• Robert Jacobs, Whole Earth or No Earth: The Origin of the Whole Earth Icon in the Ashes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

• Robert Jacobs, 24 Hours After Hiroshima: National Geographic Channel Takes Up the Bomb

• Nakazawa Keiji, Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen

• Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi, Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

• John W. Dower, Ground Zero 1945: Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors

Notes

1 The ABCC was set up in November 1946 by the U.S. National Academy of Science to conduct investigations into the effects of radiation among hibakusha in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and from March 1947, it opened an office within the Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima. Initially it was funded solely by the Atomic Energy Commission, but later the U.S. Public Health Department, the National Cancer Research Institute as well as the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute co-funded it. In November 1950, the ABCC research complex, equipped with various types of the most sophisticated medical instruments, was built on top of the hill at Hijiyama, about 2 kilometers from the city center. It was devoted to collecting a wide range of data regarding the effects of radiation on human bodies, but it provided no medical care to hibakusha. The findings of its scientific research and studies were intended to be utilized to estimate the casualties of future nuclear wars. To achieve this goal, the ABCC conducted medical examinations of many hibakusha, who were brought to the attention of the ABCC by local medical doctors and hospitals. It also asked the relatives of the deceased hibakusha to donate their bodies for autopsies. As hibakusha were always suspicious about the purpose of the ABCC’s investigation and did not trust its staff, the ABCC had to lure the people by providing pecuniary benefit. For a more detailed analysis of the ABCC’s activities, see “Genetics in the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, 1947 – 1956” in The Expansion of American Biology, ed. by Keith R. Benson, Jane Maienschein, and Ronald Rainger (New Brunswick, 1991); and M. Susan Lindee, Suffering Made Real: American Science and the Survivors at Hiroshima (Chicago, 1995).

2 During the first three years of post-war Japan strict U.S. censorship of literary publications concerning the atomic bombing led to the banning of works by Kurihara Sadako, Toge Sankichi and Ota Yoko among others. Similarly, the exhibition or publication of graphic images – both photographs and paintings – was forbidden. From July 1948, however, censorship of publications related to the atomic bombing gradually eased, due to changes in occupation policies, prompted by increasingly tense relations between the U.S. and Russia. Censorship ended in September 1951 when the Allied occupation officially ended. In the early 1950s paintings of A-bomb victims by Maruki Toshi and Iri were openly exhibited for the first time, and some relevant literary works, as well as small numbers of written testimonies by hibakusha, also began to appear. Overall, however, publications in the 1950s tended to focus upon the horrors and sufferings that victims experienced on the day that the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, rarely depicting the on-going plight that victims faced on a daily basis in the years following the holocaust.

3 Currently, there exist more than 200,000 photos including those of hibakusha in Kikujiro’s hands. Between 1989 and 2010, some of his photos were made available to various citizens’ groups at no charge and exhibited at more than 700 places in Japan. The most popular work is a set of 3,300 panels of photos entitled “Post War Japan Seen in Photos,” i.e., the photos on various important post-war political and social issues.