The “Power Elite” and Environmental-Energy Policy in Japan1

Andrew DeWit and Iida Tetsunari

On December 10, 2010, near the close of the COP 16 meeting in Cancun,2 Mexico, the international press reported that 20 national leaders, including those of the UK and Mexico, were lined up to call Japanese Prime Minister Kan Naoto.3 They sought to persuade Kan and his government not to abandon the 2008 to 2012 Kyoto Protocol approach to securing carbon reductions via explicit and compulsory targets. Their concern was well grounded. Arima Jun, the Deputy Director General for Environmental Affairs at Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, shocked the Cancun conference on December 2 with his declaration that “Japan will not inscribe its target under the Kyoto Protocol4 on any conditions or under any circumstances.”5 Translated into everyday speech, Arima’s blunt bureaucratese meant that Japan would not agree to an extension of the Protocol. Observers were so taken aback by the announcement that they assumed it must be a negotiating ploy. Surely Japan, a shrinking presence on the international stage and desperate to pump up its soft power, would not junk a treaty that earned the country valuable “global brand recognition” with each iteration of ”Kyoto.” Yet Arima’s announcement was confirmed the next day by a decision of the Japanese cabinet.

In the event, the Cancun conference decided to table decisions on whether to extend the Kyoto process to the December 2011 COP meeting in Durban, South Africa. But the Japanese Government’s determination to abandon Kyoto, the world’s only carbon-reduction agreement, remains of deep concern. It is also a serious transgression of Japan’s commitment, via the 2007 Bali Roadmap, to a two-track process of keeping Kyoto while also bringing in the US, China and other countries not yet committed to carbon cuts.

Most important for our purposes, abandoning Kyoto was an unimaginable position for Kan’s Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) Government to take barely more than a year after the country’s “regime change” election of August 30, 2009. In the election campaign and after taking office, the DPJ had stressed that energy and environmental targets were key elements of green economic growth.6 The DPJ’s target for a 25% cut in CO2 emissions by 2020 (relative to 1990 levels) was thus far more ambitious than Japan’s current Kyoto obligation of a 6% cut in emissions by 2012, versus 1990 levels.

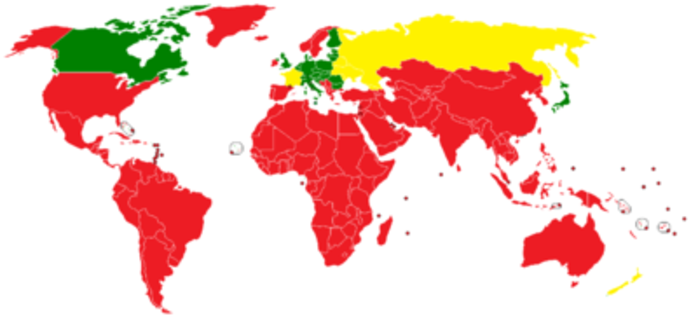

Overview map Of States Committed to a CO2 reduction in the 2008-2012 Kyoto Protocol period.[2]

Green countries = Committed to reduction

Yellow countries = Committed to 0% reduction

Red countries = Not committed to any reduction. (Wikipedia)

The DPJ’s readiness to dump Kyoto has gained some sympathy in the international debate, where a self-described “realism” insists that seeking to expand Kyoto’s compulsory national targets be dropped in favour of nonbinding, primarily sector-based agreements.7 Like any international agreement, the Kyoto Protocol faces myriad problems no matter which ideological lens we use to examine it.8 Thus in this paper we do not argue the pros and cons of the Protocol. Rather, we take a step back and look at what has unfolded in Japanese energy and environmental policymaking. On the basis of the evidence and experience,9 we argue that the DPJ’s readiness to dump the Kyoto Protocol is better understood when seen against the backdrop of the party’s collision with incumbent interests and its backtracking on virtually all energy and environmental pledges. We show that in the last months of 2010, the DPJ not only backed off from Kyoto, but also essentially shelved carbon trading,10 put off increasing the national target for renewables, and appears ready to fudge on its commitment to expand the feed-in tariff.

In other words, the Kyoto move should be seen in the domestic context of Japanese policymaking under the DPJ.11 We argue that Japan’s problem is the political economy of vested interests in this policy area rather than the fine print of the Kyoto Protocol. Indeed, Japan’s domestic opponents of Kyoto are not aiming their obstructionist efforts at the Protocol alone, but more generally at the use of compulsory targets and rules. And they are not doing this on the basis of an objective determination of the overall costs and benefits, for Japan, of taking a leading role in reducing CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions, ramping up the use of renewable energy, and otherwise achieving low-carbon growth.

Rather, these vested interests are protecting their turf and their own bottom lines. They include monopoly electrical utilities. These actors have the domestic market cut into 10 fiefs and want to protect that dominance against competitors and energy alternatives that might threaten their plans to expand nuclear power. The vested interests also include carbon-intensive industries such as cement, steel, and other industries. They are averse to any rules that might impose costs on them, even if such might be in their own long-term benefit through enhanced competitiveness. Together with an accommodative economic bureaucracy, these interests have long been accustomed to crafting their own voluntary commitments, or at the very least deflecting pressure for compulsory targets by making them so low as to be meaningless. They want to go back to the comfortable status quo that prevailed before regime change, and are making significant headway towards that end.

This article will proceed as follows. First, we sketch the background of the post-oil shock years and the relevant details of the policies in question. We thus begin with a short detour from the main narrative of the past year in DPJ climate and energy policymaking. But we believe this detour is necessary. In Japan as well as the US and several other countries, the conventional wisdom in the debate on energy and environmental policy is that reform perforce involves imposing heavy costs on businesses and consumers. With that assumption in the foreground of the debate, policy immobilism is only to be expected. Visibly increasing costs on well-mobilized interests is one way that governing politicians can become opposition members or even unemployed politicians. We show that this assumption about costs is as questionable as the once widely held notion that the financial sector required more deregulation in order to maximize socially beneficial innovation. We present evidence that the extra costs criticism directed at smart energy and environmental policy is largely the self-interested claims of such incumbent interests12 as the monopolized utilities, carbon-intensive businesses, the nuclear sector, and the economic bureaucracy. Incumbent interests have a long history of opposing socio-economic development and other kinds of progressive change when they do not perceive it to offer them a constant or increasing share of the economic pie.13

Following our sketch of the post oil shock background of Japanese energy and environmental policymaking, we examine what has transpired in the wake of the election. We show that the economic bureaucracy, the power elite, and the carbon-intensive business elite have used a variety of institutional resources to recover their influence and regain leadership in environmental and energy policymaking. And finally, we offer some ideas on how Japan might address these problems and position itself for sustained leadership in the energy-environmental revolution.

The Prize

The political economy of Japan’s energy and environmental policy needs to be seen against the backdrop of rapidly expanding threats and opportunities. The former include accelerating climate change as well as the rising risks and costs of such conventional energy sources as coal, oil, natural gas and nuclear. These often overlapping threats (e.g., fossil fuel use exacerbates the climate problem) have spurred many governments to action. Smart action can reduce vulnerability to price shocks and other negative externalities associated with reliance on conventional energy, especially imported fuels. Smart energy and environmental policy also holds forth the opportunity to gain an expanding share in the rapidly growing green energy economy. Over the past year, as Japan’s new national government has backtracked on most of its energy and environmental commitments, its Chinese, German and other competitors have bolstered their own policies for leading the ongoing energy-environmental revolution.14

There is significant evidence that the global energy economy is at a very critical turning point, as financial flows are following smart policy. The September 2010 Renewable Global Status Report shows that the USD 30 billion invested in renewable energy capacity and manufacturing plants in 2004 had expanded to USD 150 billion by 2009. It also shows that 2009 was the second year running in which “more money was invested in new renewable energy capacity than in new fossil fuel capacity.” Reflecting their robust policies, Germany and China were the investment leaders (at about USD 25-30 billion each), with the US a distant third (at just over USD 15 billion) followed by Italy and Spain (roughly USD 4-5 billion each).15

In addition, even conservative estimates of energy demand project it to increase by 44% between 2007 and 2035.16 Meeting this demand will require trillions of dollars in new investment. In the developed and especially the developing economies, massive amounts of new energy investment are awaiting price signals for emissions costs as well as the potential for fossil fuel-price increases. Uncertainty about these costs is very troubling to institutional investors, as power generation facilities are enormous capital expenditures that are written down over decades. Just before the Cancun meeting, institutional investors from all global regions and managing USD 15 trillion in funds made a very public call for “strong government policies that reward clean technologies and discourage dirty technologies.” They added, “a basic lesson to be learned from past experience in renewable energy is that, almost without exception, private sector investment has been driven by consistent and sustained government policy.” And they explicitly called for the robust emissions reductions targets, policies to accelerate the uptake of renewable energy, and other mechanisms that the DPJ had promised in 2009.17

Because of these pressures, the International Energy Agency (IEA), hitherto dubious about renewables, now emphasizes the need to invest USD 5.7 trillion in renewables between 2010 and 2035 to cope with rising energy demand, the peaking of conventional oil supplies, and the threat of runaway climate change.18 The IEA’s 2010 World Energy Outlook also recognized that the peak in conventional oil production had likely been reached in 2006, meaning costs are virtually certain to increase.19 With the prices of conventional fuels climbing whereas the costs of renewables are dropping, independent analyses indicate that several renewable options are already cheaper, per kilowatt hour of power generated, than fossil fuels and nuclear power.20 Since Japan’s electricity prices are already comparatively quite high,21 it is easier – than say in the US22 – for the country to achieve grid parity with renewables and start reaping the benefits of cost reduction from price declines as the facilities diffuse.

Let us look more closely at Japan’s structure of incentives to act. The first and most obvious incentive is that Japan relies on oil for 44% of its primary energy. It also gets over 90% of that oil from the unstable Middle East. Japan also uses a lot of coal, since in 2008 just over 60 gigawatts of its slightly more than 280 gigawatt power generating capacity was coal-fired, and the country used just under 33% of the OECD total consumption of 174.3 million tonnes of coking coal.23 Virtually all of this coal is imported as well, from suppliers who of late are struggling to meet demand in the face of infrastructure bottlenecks, more frequent natural disasters, water constraints and other issues. Japan’s significant consumption of natural gas and uranium are also fraught with uncertainty and price problems, especially as rapidly growing countries such as China and India compete for these finite and geographically concentrated resources.

But Japan is blessed with significant endowments of renewable resources through geothermal, wind, wave, solar and other potentials. Japan’s geothermal potential is the world’s 3rd greatest,24 it has significant wind resources,25 as well as substantial biomass, solar, wave and tidal potential. On these bases alone, one would expect that its national government would be the frontrunner in deploying robust policies to develop potentially low-cost energy resources whose expansion would mean less money flowing overseas. Japan’s purchase of oil alone cost YEN 16.63 trillion, 22.85% of all imports, in 2008.26 Substituting locally-produced renewable energy for such imports would be a significant fillip to tottering local economies. It would provide a valuable source of additional income to hard-hit households, farmers and small businesses.

Japan was in fact an early mover in this direction, as the national government provided significant incentives to develop and deploy. In 1974, for example, Japan (along with the United States) responded quickly to the oil shocks with policy and technological innovations in the renewable-energy field. Among other approaches, Japan introduced the “Sunshine Project” (Sanshain Keikaku), followed later by the subsidiary “Moonlight Project” (Muunraito Keikaku) in 1978.27 The former project sought to promote research and development in energy alternatives, especially solar power, while the latter focused on energy saving. In 1980, the project was designated as the responsibility of a new agency “New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization” (NEDO). The creation of NEDO also saw the institution of a project subsidy system, national targets, and the development of a legal framework for fostering renewable energy.

The Sunshine Project was given a further boost in 1993, in the first years after the collapse of the so-called “bubble economy.” This boost came from the launch of the “New Sunshine Project” and the consolidation of various sustainable energy projects into a more coordinated effort. This reorganization was accompanied by the introduction of various subsidy programmes to encourage public institutions, households and commercial facilities to install solar and other sustainable technologies. These projects were all focused on using the public sector to encourage innovation as well as foster the markets needed to scale up deployment and thus ratchet down the price of power produced through renewable energy.

But just as the policies started to gain traction, they were cut back. In a lamentable demonstration of the knee-jerk “market fundamentalism” of the former PM Koizumi Junichiro years (2001-2006), Japan reduced and then in 2005 eliminated its solar subsidy. The timing could hardly have been worse, as the solar market was taking off globally. Eliminating the subsidy greatly eroded the incentives in Japan’s national regime, which lacked the robust policies, especially the feed-in tariff, that had been deployed in Germany and elsewhere. Japan’s growth in solar energy installation and production capacity had led the world until the mid-2000s, but was then left behind by Germany’s spectacular performance. In 2006, right after Japan nixed its solar subsidy, it installed only 300 megawatts of new solar installations compared to Germany’s 750 megawatts. Overall, Japan has seen its share of global production in solar panels fall from 50% in 2005 to 14% in 2009.28

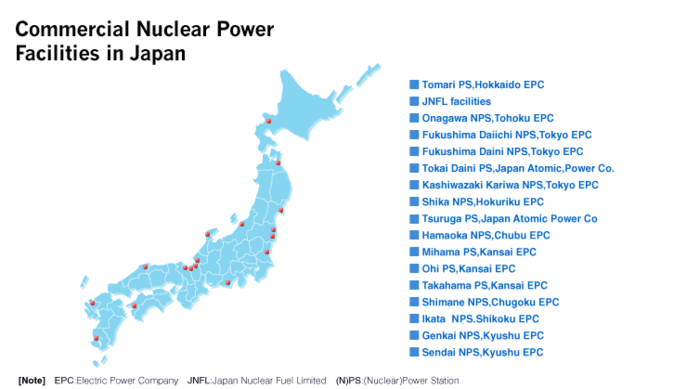

At the same time, the nuclear lobby was locking up even more policymaking space. Japan’s post-oil shock policies included massive support for nuclear power,29 and it has grown into a powerful vested interest at the core of the country’s 10 regional electrical monopolies. As a result, the pre-DPJ energy and environmental policy elite were betting heavily on expanding nuclear power as the answer to the problem of power supply as well as GHG emissions cuts.30 As concerns about climate and conventional energy costs mounted in the early 2000s, nuclear power emerged as the favourite alternative. Thus the 2010 Basic Energy Plan aims at making nuclear power the key driver in Japan’s electricity supply by raising its role to about 50 percent of electricity supply by 2030. The authorities plan to realize this objective by constructing 9 new nuclear plants by 2020 and at least 14 by 2030.31 The nuclear lobby has much of the energy R&D budget locked up32 and has the support of broad swaths among the political and bureaucratic elite in the central government. They see nuclear power as the only realistic option for reducing dependence on fossil fuels and cutting emissions, and are also keen on making it a major export business.

Hence, one more reason for Japan’s post-2000 slacking off in promoting renewables was that there was a favoured alternative power source. Another was that the big carbon-intensive (steel, cement and the like) business community gained influence in the policymaking process.33 No matter the image of Japan as a high-tech, green nirvana, the peak industry association, Nippon Keidanren, has long promoted carbon-intensive industries. They have a powerful influence on energy and environmental policymaking, especially in an era of weak governments. Moreover, Keidanren’s Chair or Vice-Chair is by convention drawn from the nuclear-focused utilities. This fuses the interests of the utilities and their major corporate customers, who share the conviction that alternative energy is unreliable and costly, and that there is no realistic alternative to the status quo. This combination of tightly fused organization and significant clout of incumbent interests has enabled the business community to reject targets that it does not like.

Another source of strong business opposition to robust policy is the fallout from the bubble’s collapse. Japanese firms slowed their efficiency and other clean investments in the 1990s as they fell into the long balance-sheet recession and deleveraging that followed the implosion of the land- and stock-price bubble. Japan’s energy efficiency, per-capita carbon emissions and other indices remain among the best in the big OECD countries, but they are not keeping pace with leaders such as Germany.34

We can see the results of these factors in policymaking outputs. The incentivist climate and energy policy after the oil shocks shifted to an emphasis on moral suasion of the public. Hectoring the public was less effective than adopting the kinds of targets and rules for industry that made Japan an environmental leader in the wake of the oil shocks. But Japan’s monopolistic utilities and carbon-intensive firms dominated peak business associations and thus largely came to control the LDP’s energy and environmental policies. In consequence, the business community and economic bureaucracy cooperated on voluntary programmes and self-regulation, a recipe for tardiness.35

Regime Change on a Green Platform

Japan’s August 30, 2009, general election for the Lower House (or House of Representatives) of the Diet saw the long-governing LDP decisively turned out of office. The LDP had held office virtually since its foundation in 1955, spending less than a year out of power in 1993-94 while an unwieldy 8-party coalition took office and then ended in rancour. Much like the 2008 election of Barack Obama as US President, with strong Democratic majorities in the US Congress, the DPJ’s ascent was widely expected to bring a major shift in Japanese policymaking, particularly concerning energy and climate change. The DPJ was explicitly committed to changing policies as well as policymaking institutions, so as to amplify Japan’s capacity to take advantage of the economic opportunities presented by deepening global climate and energy crises.36

As to policies, the election campaign saw Okada Katsuya, of the DPJ’s Global Warming Countermeasures office (and currently its Secretary General) proclaim that under a DPJ government the LDP’s “embarrassing targets” for CO2 emissions reduction and renewable energy would go back to the drawing board.37 On emissions, he promised instead the more robust goal of achieving a 25% cut in carbon dioxide emissions by 2020 (versus 1990 levels). The current prime minister, Kan Naoto, also declared during the campaign that the real world does not fit into bureaucratic fiefs. He made clear the DPJ’s determination to make a clean break from years of environmental and energy policymaking led by the Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry (METI).

Another important DPJ election promise was to adopt a comprehensive and gross feed-in tariff. This promise meant expanding Japan’s existing feed-in tariff (implemented on November 1, 2009) to include such renewable energy sources as wind and geothermal. It was also a promise to use the feed-in tariff to purchase all the power produced by a household (hence “gross”), rather than just the “net,” or surplus power produced after household consumption is subtracted. Feed-in tariffs are proven policies for supporting the uptake of wind, solar, biogas and other renewable energy technologies through encouraging household, community, small business and other decentralized production for the electrical grid. The tariff pays an increment above the base price of electricity to foster a stable, long-term market for renewable power and thus accelerate technological improvement and diffusion of power generation. As we explain in more detail below, the METI in fact drafted Japan’s current feed-in tariff programme. But in a sharp contrast to the DPJ commitment, the METI scheme is essentially limited to solar energy and applies only to electricity produced in excess of the producing household’s consumption. The METI feed-in tariff was clearly designed as a pre-emptive means to allow vested interests in the bureaucracy and the power sector to retain control over policymaking as well as energy options in this strategic area.

A further goal of the DPJ was to increase the country’s use of renewable energy to 10% by 2020. This goal was to supersede the current compulsory target of merely 1.63% of power by 2014, which appears to be the lowest target among the developed countries that have adopted such incentives. The German target is, by contrast, 45% of power by renewables in 2030. Scotland aims at 80% by 2020, and China’s official goal is to generate 16% of all energy via renewables by 2020, with a very recent commitment to an astounding 500 gigawatts of renewables by 2020. The US Navy is even committed to 50% of all energy via geothermal, solar, wind, 2nd generation biofuels, and other renewable sources by 2020. Japan’s current RPS target is in fact so low that it is actually less than the utilities’ extant renewable generating capacity. As a result, the electrical utilities simply “bank” the excess of sustainable energy production and apply it to their obligations. The effect is to further erode incentives for expanding the provision of electricity via renewable sources.

With all this as background, a major policy imperative of the September 2009 Hatoyama government was to use green growth policies to put Japan back in the race. One of the government’s first two cabinet committees was devoted to the environment and energy. In tandem with that institutional change, DPJ Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio repeatedly stressed the party’s election commitment to slash Japan’s greenhouse gas emissions 25% by 2020 relative to 1990 levels. Many of the DPJ leadership are former LDP politicians, with many years of experience of the party and its policymaking. So they were quite well aware of the politics behind these low policy targets, and argued they could do a better job of governing. Many of them emphasized that increasing numbers of governments, including China and Germany, were using robust targets as a means to promote sustainable growth. Getting into the lead of rapidly expanding energy and environmental markets was attractive in the face of worsening energy and environmental crises. Confronting an ageing and debt-ridden polity, these politicians saw green growth as one option for alleviating Japan’s tough fiscal choices and preventing yet another “lost decade” of subpar economic performance.

But the DPJ’s climate hawks soon ran into major setbacks. They did not adequately police personnel policies, nor did they foresee the power of vested interests to use institutional resources to reproduce the status quo.

The Revanche of the Vested Interests

Japan’s political regime change was heralded as an opportunity to break free from bureaucratic politics. In climate and energy policy, there was an opening for smart policy intervention to shift the overall political economy’s calculus of costs and benefits. Japan’s METI and other economistic bureaucratic agencies faced a diminution of their powerful influence in policymaking. In the wake of the election, there was great consternation in Kasumigaseki (Japan’s bureaucratic district in Tokyo) that there would in fact be profound institutional and policy change. The METI was generally seized by a deep concern that it would become irrelevant in policymaking. But key streams within the DPJ include representatives from the trade unions of incumbent, energy-intensive industries as well as other groups close to the METI. These staunch allies of the status quo in climate and energy matters managed to get their hands on personnel placement for the new cabinet. So even as the new government got underway, bureaucracy-dominated policymaking in energy and environmental policy was already on the comeback trail through personnel appointments.

One of the key areas where there was a movement back towards the METI bureaucracy included a new committee of cabinet members whose areas of responsibility include global warming-related issues. The DPJ aimed to transcend bureaucratic fiefs in dealing with global warming, and so quickly set up this committee. The relevant ministries’ top officials, including the Minister and Vice-Minister were named to it. In October of 2009, it formed a task force to determine what measures should be used to achieve the DPJ goal of 25% CO2 reductions by 2020.

Here is one example where vested interests have skillfully used institutional resources. In order to revise the LDP-made “embarrassing numbers,” the task force used the same static projections drafted by the original five research centers that the LDP had relied on.38 This use of static modeling of the economic cost of cutting emissions was both unwise and unrealistic. It was unwise because the previous LDP regime and the METI had chosen these kinds of studies in order to stress costs and thus provide a rationale for adopting a low target. It was also unrealistic because the models assumed no change to the basic structure of the economy over the reference period. But recall the decade of the 2000s. That decade saw the internet revolution reshape music and telephony, the implosion of history’s biggest asset bubble, and the take-off of the green energy revolution. Against that backdrop, it seems absurd for any study to assume no change in the Japanese economy over the next decade. The reliance on these outmoded studies provoked plenty of heated exchanges, but they still served to frame the deliberations.39

This problem should have been foreseen. The office in charge of the process was the Cabinet Secretariat in the Office of the Assistant Chief Cabinet, a section of the cabinet-support structure whose core staff are METI people. This office can be seen as a stronghold for interests who are deeply opposed to the Kyoto agreement. The new regime, though committed to mastering the bureaucracy, neglected to dismantle this entrenched structure of personnel. Hence there was a carryover of Anti-Kyoto bureaucratic staff from the LDP regime to the new DPJ regime. This is another reason the task force failed to function in a way that was hoped for.

A similar phenomenon quickly became evident in deliberations over the revamped strategy for economic growth, a debate that began in the final days of 2009. Japan’s excessive dependence on external demand had seen it hit very hard by the global financial crisis and its fallout. Wedded to vested interests and the status quo, the LDP had been incapable of constructing a credible economic strategy in the face of the crisis. This lack of policy ideas helped cost it the election. But the new DPJ regime also had no serious economic blueprint, and hence found itself floundering when it sought to take the initiative in policy design. The continuation of the economic crisis throughout 2009 and 2010 saw the DPJ increasingly rely on the METI for ideas on what to do. The METI was, of course, happy to oblige, and naturally put vested interests front and centre. Against the broader backdrop of a retreat from small-state and free-market nostrums in favour of more activist government, 2010 thus saw the rise of an “all Japan” public-private push for infrastructure and nuclear exports.40

As with anyone who follows the news in Japan, the METI and its client industry sectors were aware that there had to be change because of Japan’s “Galapagos” problem. Japanese technology, in a variety of sectors, has often been developed for use only in the domestic market. But the domestic market is shrinking due to ageing as well as the declining population. Japan faces dwindling economic prospects unless it can grow beyond its inward focus and its carbon-intensive industries.

In addition to stressing sustainable energy, a proper policy response to Japan’s dire straits would be to foster a knowledge economy. Japan needs a much more diverse engagement with emerging opportunities in a rapidly changing global political economy. But METI and other economistic bureaucrats have only a limited grasp of how to move towards a knowledge economy as opposed to boosting narrow sectors. Rotating through their jobs every two years, they are not particularly innovative thinkers. So one should not be surprised that the economic bureaucracy regards its outdated, 20th-century paradigm of energy policy as in fact sound.

This bureaucratic bias towards the status quo was strikingly evident in the bureaucracy’s push to get nuclear exports to the top of the agenda. At the end of 2009, Japan lost out to Korea in a nuclear export deal to the UAE, and also to Russia on a deal with Vietnam. These losses became a strong spur to a narrow-minded nationalist impulse that found its expression in the “all Japan” framework for promoting nuclear exports. The culmination of this was seen right after the Obama Administration held its Nuclear Security Summit in Washington on April 12-13 of 2010. In June 2010, Japan was holding bilateral negotiations on nuclear exports to India, not a party to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. PM Kan Naoto had promised leadership towards a “world without nuclear weapons,” but failed to explain his dealings with India, including how it would not pose a threat of proliferation. Far from being a realistic strategy for a new growth area, greasing nuclear sales with yet more public sector money and foreign-policy effort is extremely risky both in terms of its economics and its implications for international politics.

Even the IEA, a strong supporter of nuclear power, does not expect it to increase much as a supplier of global energy needs.41 And as the American investor coalition, Ceres, notes in a July 7, 2010 study, utilities that deploy nuclear power facilities are taking on investment risks that make them increasingly unattractive to investors and financial institutions. In this respect, it is important to note that the Ceres group represents USD10 trillion in institutional investor funds. Global investors increasingly believe that the conventional energy sector is a risky bet, and are shifting their investment strategies accordingly.42 With its flawed focus on nuclear as the only serious alternative energy source and energy-generation export, Japan risks pricing itself and its products out of both the green and the conventional global markets.

The METI versus the Environmental Ministry

In 2010, Japan also saw conflict among the ministries and their fiefdoms intensify. One of the areas of conflict was seen in the “medium-to long-term roadmap” that was started in the offices of the Environmental Ministry. The Environment Minister Ozawa Sakihito was chair of the global warming-related cabinet committee and also took questions on the midterm report from the task force just before the 2009 COP 15 summit in Copenhagen. Afterwards, the task force initiative slacked off greatly, and instead the central environmental council, a committee run by the Environmental Ministry, set to drafting the roadmap.

As noted earlier, the task force was originally the agency charged with the job of designing the means to achieve the 25% cut in CO2, which was the scenario for the basic law on global warming countermeasures. The roadmap was in large measure a continuation of this process; but under the rubric of “political leadership,” deliberations over the means were moved from the global warming-related cabinet committee (which had set up the task force) to the Environmental Ministry. But in the background, the METI saw this shift as an opportunity and began working on its own basic energy plan. The METI plan eventually took precedence over what was going on in the Environmental Ministry. Part of the reason appears to be inadequate deliberation over the roadmap in the central environmental deliberation committee, whereas the METI basic energy law had the grounding of law (having been first formalized in 2003). This automatically gives the latter more credibility and legitimacy in the policymaking process. The Environmental Ministry’s deliberations on the roadmap began in 2009, and the METI started its deliberations on the basic energy plan in March of 2010, rushing to catch up. METI certainly sped through the process, as both documents were brought into Cabinet debate on June 18 of 2010.43

One clear object of the economic bureaucracy was to gut carbon trading. Among the DPJ’s global warming countermeasures, cap and trade received an enormous amount of criticism from the METI as well as from business circles. The abuse heaped on the proposed trading scheme was in fact roughly equivalent to the torrent aimed at the target of cutting CO2 by 25% by 2020. A September 2010 survey by Keidanren not surprisingly found that 61 of 64 respondent firms opposed carbon trading as a threat to competitiveness.44

These kinds of criticisms fed into the focus of Cabinet deliberations on the global warming countermeasures basic law. Behind the scenes of the deliberations in the cabinet committee, there was intense lobbying concerning the content of the law. The overall process featured the METI’s top-level political representatives backed up by the economic bureaucracy and simply overwhelming other voices in the party. The bureaucrats were so skillful in working up “paper bombs” and otherwise shaping the flow of information that overall “political leadership” was essentially neutered. It is a prime example of how the bureaucracy is able to shape policymaking when it has a clear and consistent agenda, backed by vested interests.

As matters stand, the result is a basic law on global warming countermeasures that is a painful compromise among competing bureaucratic objectives. The 25% target was rendered into one that is to be achieved only if there is agreement to join in by all of the major countries and only if that agreement is part of an international mechanism that is deemed to be effective. The interpretation of the various terms used in that phrasing is of course very much open to debate. Moreover, nuclear power is given explicit targets and otherwise represented as the main means to achieve energy security, for which the public’s “understanding and trust” is to be gained. And carbon trading was clearly to be undertaken less as a move towards overall cuts and instead as a continuation of the present voluntary carbon market at the national level, which is based on emissions per unit of production of specific goods.

In the end, the economic bureaucracy managed to secure even more than those concessions. On December 28, 2010, the Japanese Government announced that it would “continue to study carbon trading taking into account various opinions.”45 It would seem unwise to expect much of anything.

Setting the Agenda in Advance: The Feed-in Tariff

The feed-in tariff is another area of rollback. Before the 2009 election, the METI had already decided to prepare for regime change by crafting a feed-in tariff. It believed this would be its last chance to make a major impact on policymaking. Working fast, the bureaucrats had come up with new energy legislation by July 2, 2009. They then got it proclaimed on August 31, the day after the election. Hence, in the midst of that hot summer’s election campaign, they were able to institutionalize a feed-in tariff for surplus solar power. In choosing a feed-in tariff aimed only at surplus power, and only at solar (in spite of Japan’s excellent geothermal, wave and wind resources), METI was clearly seeking to hamstring the country’s potential to shift towards sustainable power sources at the expense of the power elites’ nuclear plans. We can see the scheming in the structure of the feed-in tariff. The feed-in tariffs that have been adopted in over 80 countries and sub-national governments are generally “gross” feed-in tariffs. As noted earlier, that means the tariff applies to all power produced and not just excess power. Moreover, they support diverse renewable energy sources rather than merely solar. But Japan adopted a very restricted type of feed-in tariff because the bureaucracy wanted it that way.

The METI was and remains steadfastly opposed to adopting the kind of feed-in tariff that has been such a striking success in Germany. Germany is not especially well-endowed with renewable resources, since its insolation (amount of sunshine) is roughly equivalent to the US state of Alaska. It has only moderate wind resources, is not highly seismic, and has a limited amount of coastal area for tidal and wave power. Germany is thus not the most likely candidate country for leading a renewable industrial revolution. But it has an advantage on governance: a bipartisan consensus on using smart policy (especially the robust feed-in tariff) to increase the country’s use of sustainable energy resources and thus cut the cost of using conventional energy. Over the past decade, the Germans have ramped up their ability to generate electricity from renewable sources to 16.3% as of 2010, thrice the level it was 15 years ago. And they have done this while building a cutting-edge export industry in environmental and energy products and technologies, as well as fostering 300,000 jobs that pay well and contribute to a sustainable economy, contribute to reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, and contribute to reductions in the cost of imported fossil fuels. These positive externalities cost German households connected to the electricity grid an extra three marks (roughly the cost of a loaf of bread) per month.

As noted, the DPJ promised to revise the policy that METI had got introduced, and adopt a comprehensive and gross feed-in tariff. But the bureaucrats managed to undermine movement in this direction. After taking office on September 16, 2009, the DPJ faced an immediate challenge of what to do with the bureaucratically determined net feed-in tariff applied to solar and ready for implementation on November 1, 2009. The best strategy in the face of this momentum would have been to temporarily delay the introduction of the feed-in tariff, for about six months from its scheduled implementation. The time could have been used to redesign the policy. Indeed, some elements of the new regime’s Upper House coalition were amenable to this strategy. But overall there was a tacit acceptance of moving in the pre-established direction. This complacency also allowed METI-centered bureaucratic politics to rebound. By the middle of November of 2009, opponents of the gross feed-in tariff comprised the bulk of the membership of the committee for (ostensibly) studying how to revise the policy.

We also pointed out that the METI has long been negative about renewable energy in general as well as the feed-in tariff in particular. The ministry adopted the feed-in tariff not with the objective of diffusing renewable energy as much as possible but rather with the objective of stalling progress as much as possible. One of the mechanisms for this is projecting system costs at inordinately high levels while not deploying adequate mechanisms to encourage declining costs for the renewable energy purchased via the tariff. This is very far from international best practice, where feed-in tariff policies are deliberately shaped to structure powerful incentives for cost reductions and technological advance.

A second problem is seen in a rather naïve approach to technology. Key to diffusing renewable energy is smart use of the electrical grid in order to balance the intermittency of renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. But in Japan storage batteries are mooted as the means to deal with the variable production from most renewable energy sources. The problem is that storage batteries are an extremely expensive and unrealistic means of achieving this end.

Another problem is a biased kind of free-market fundamentalism. In the METI’s draft to revise its own in-house feed-in tariff, it proposes that all renewable energy technologies be treated equivalently, with the same level of tariff support. This kind of approach to encouraging renewable energy technologies has already failed in several countries, and the evidence is available for perusal by any who care to look. The relative maturities of renewable energy technologies varies, and so most countries set the tariff for wind power, a mature technology, far lower than that for photovoltaic, which is still in its take-off phase. But the METI is adamant. They argue that they seek to diffuse the maximum amount of renewable energy at the lowest possible cost.

These are just some of the reasons it is reasonable to assert that the feed-in tariff in Japan is again being deliberately hamstrung so that the diffusion of renewable energy is a high-cost venture that imposes onerous burdens.

This is all bitterly ironic when one reflects on the goals stressed during the 2009 election and afterwards. A great many households, farmers, and other interests are eager for the opportunity to earn income from wind, small-hydro, geothermal, biomass and other renewables. They are eager to receive the opportunities enjoyed by many of their counterparts in Germany, Thailand, Italy, the UK, Canada’s province of Ontario, and elsewhere.46 But perhaps the greatest irony here is that the gross feed-in tariff proposal, as it stands (and seems likely to be adopted) maintains the purchase of only the excess power produced by households. In other words, it is “gross” in name only, and through the magic of bureaucratese is almost certain to remain “net” in fact. This result is in direct contradiction to the DPJ’s election manifesto, and a profound example of the lack of political leadership.

Conclusion

What do we learn from this? One clear lesson is that the old interests have reestablished themselves. The LDP’s energy and nuclear power policy circles were centered on the Federation of Electrical Power Companies of Japan (Denjiren),47 Nippon Keidanren, and the regional utility monopolies. As noted earlier, the Nippon Keidanren itself regularly has a representative from the power sector as Chair or Vice-Chair. The policy tribes in the LDP’s councils were heavily influenced by these organizations. And under the DPJ, we see energy policy being heavily shaped by Diet members who are connected to labor unions (or are former members of labor unions) from the utilities as well as firms that are big electrical users. Indeed, current energy policy is in many respects even more outmoded than was the case under the LDP.

So why did the laudable climate and energy goals make it into the election manifesto in the first place? One reason is that the incumbent interests were left on the sidelines during the drafting of the election promises. Okada Katsuya and other quite green DPJ members took charge of drafting the environmental and energy parts of the manifesto, and they put in the ambitious targets of 25% CO2 cuts by 2020, the cap and trade commitment, and the commitment to a feed-in tariff that fully supported renewable energies.

Another reason this bold environmental and energy policymaking made it into the manifesto was that the document was not cleared through intraparty debate prior to its adoption. The goal of the DPJ in the election campaign was to create as much difference between itself and the LDP as possible. Being critical of nuclear power offered the opportunity of just of doing just that. Moreover, at the time, the party was not as powerfully subject to pressures from bureaucrats and industry associations. It thus had the autonomy to make bold commitments to environmental policy. But with the party now in office, the influence of bureaucrats and the industry associations is powerful at every stage of the policymaking process. As a result, much of the manifesto is being completely ignored.

And as has become clear over the past year, there has been little change in the role of Kasumigaseki. At least in the energy and environmental policymaking arena, the personnel, the institutions, the deliberation committees and their structure, and the other avenues and institutions have largely remained unchanged compared to what was in place before the regime change election. This may be the fault of not having a blueprint for change in place prior to the election. At least in this policy area, the DPJ clearly did not think hard enough about the details of recasting the relations between politicians and bureaucrats.

So being willing to dump Kyoto would indeed seem to be part of a larger post-election politics that seeks to reproduce and cater to vested interests. Coddling vested interests has, of course, been an unfortunate and costly characteristic of much of Japanese economic policymaking over the past two decades. Shocked by the bursting of the bubble, ageing, increasing indebtedness, rising unemployment and other challenges, core interests have become defensive and risk-averse (except with public money), rather than expansive. The upshot at present is that Japan, the country once renowned for smart industrial policy, appears ready to forfeit the already massive opportunities afforded by renewable energy and the smart grid.

Clearly, Japan’s environmental and energy policymaking has to move towards a 21st-century paradigm. It has to shift from nuclear power and fossil fuels to renewable energy and energy conservation. It also has to shift from an undue concentration on large firms and afford more scope for innovative small firms. And it has to move away from rigid top-down structures to more fluid networks, from heavy industry to a focus on knowledge and the environment. Good public policy is essential to facilitating that transformation. But it is unclear whether the DPJ can return to its earlier commitment to smart, green goals and help realize Japan’s real promise.

Andrew DeWit is Professor of the Political Economy of Public Finance, Rikkyo University and an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator. With Kaneko Masaru, he is the coauthor of Global Financial Crisis.

Iida Tetsunari is the Executive Director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies, a non-profit independent research institute based in Tokyo, He has served as a member of the Government committee on energy policy and renewable energy of METI and a member of the National Environmental Council of the Minister of Environment.

Recommended citation: Andrew DeWit and Iida Tetsunari, The “Power Elite” and Environmental-Energy Policy in Japan, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 4 No 4, January 24, 2011.

Notes

1 Andrew DeWit gratefully acknowledges JSPS Research Grant (#) for funding this research.

2 The COP acronym stands for the “Conference of the Parties,” which meets annually to work on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. On the conference and related matters, see the comprehensive overview at: http://unfccc.int/2860.php

3 The December 10 BBC reported it as a “diplomatic assault on Japan in the hope of softening its resistance to the Kyoto Protocol”: link.

4 The Protocol covers the period from 2008 to 2012, and has been ratified by 191 countries, though not the United States. It obliges 37 industrialized countries to reduce their CO2 emissions by an average of 5 percent relative to 1990 levels by 2012. There is as yet no international agreement on carbon emissions reductions to cover subsequent years. A concise description of the Kyoto Protocol and its mechanisms can be found here.

5 This position was reported on by UPI on December 2, 2010.

6 The policy commitments caught the attention of overseas observers. In the August 28, 2009, edition of the New York Times, Lisa Friedman noted that the DPJ targets were very robust and a stark difference from the LDP regime: link.

7 For example, Michael Schellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, of the Breakthrough Institute, unreservedly supported the DPJ position in a December 7, 2010 explanation of “Why Japan Disowned Kyoto.” They argue that the “zombie UN process” with its focus on “top-down emissions reductions” needs to be set aside in favour of the Copenhagen process and its “more limited national commitments to deploy low-carbon technologies, reduce energy intensity, and take other measures to reduce, or at least slow the growth of emissions.” Link

8 Of course, the Kyoto Protocol’s biggest problem is that it is simply inadequate in the face of potentially runaway global warming.

9 One of the present authors (Iida Tetsunari) has been directly involved in national energy and environmental policymaking for over a decade. Part of this article draws on his “Why has the new government’s energy and environmental policies gone into reverse” [Shinseiken no kankyou, enerugii seisaku ha naze gyaku-funshashitaka?], Sekai, January 2011.

10 On the carbon-trading backpedalling, see Andy Sharp “Japan Drops Cap and Trade,” December 30, 2010.

11 One could argue that most countries’ climate policies are dominated by incumbent energy interests, which focus their lobbying in national councils of power. Fossil fuels provide 86% of global energy, and their exploration, development and retail industries are the world’s largest and most profitable industry. Their products are also responsible for 60-70% of greenhouse gas emissions. Securing effective international agreement to ameliorate this destructive political economy is thus inherently difficult but imperative.

12 We use “incumbent” here to refer to the vested interests sketched above. “Incumbent” in this usage means currently in place, and suggests incentives to protect that position against change and competitors.

13 One example is seen in the first industrial revolution and its “political replacement effect,” which Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson outline in their “Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective,” in American Political Science Review, Vol 100 No 1 February 2006: link.

14 Moreover, Japanese urban governments in Tokyo and Yokohama are seeking to implement, in their jurisdictions, some of the very carbon reduction, renewable and other policies that the DPJ is backing away from: link.

15 The report, whose financial data can be found on page 27, is available for download from the REN21’s website.

16 See the analysis at the US Energy Information Administration’s May 25, 2010 released “International Energy Outlook”: link.

17 The group’s November 16, 2010 press release can be found here.

18 See the IEA’s 2010 World Energy Report summary factsheet here.

19 For an analysis of the IEA report, see this link.

20 For the US, see Figure ES-2 in the July 8, 2010 “The 21st Century Utility: Positioning for a Low-Carbon Future.” An overview and download link can be found here. For the EU, see the main tables in “Energy Sources, Production Costs and Performance of Technologies for Power Generation, Heating and Transport,” EU Commission Working Document SEC 2008 2872, November 13, 2008: link. It is instructive to compare these data with such figures as the October 12, 2007 data from Japan Nuclear Research and Development Agency: link.

21 A recent comparison of power prices, for households and for industry, and based on IEA data, can be found here.

See also, IEA, 2010. Energy Prices and Taxes: Quarterly Statistics 3rd quarter 2010. IEA Publications: Paris.

22 America not only has plenty of cheap coal-fired power to hinder the diffusion of alternatives, but it is currently enthralled by a shale gas bubble that allies of the conventional energy sector deem a “revolution” offering a century of low-cost supply. The bubble is blunting incentives to adopt renewable power. On the hype, see “CERA Week: Shale gas can be a “Game Changer” for North America’s energy future,” in E&P March 10, 2010: link.

23 See International Energy Agency, “Coal Information, 2010,” especially tables 5.1 and 5.3. Note that coking coal is used in making steel in blast furnaces, and at present has no practical substitute.

24 As Lester Brown points out, Japan was an early leader in exploiting its geothermal resources, but slacked off greatly over the past two decades. But an indication of the potential is seen in the fact that Japan has 2,800 spas, 5,500 public bathhouses, and 15,600 hotels and inns that use geothermal hot water. See Brown, “Geothermal: Getting Energy From the Earth,” Earth Policy Institute, August 31, 2010: http://www.earth-policy.org/book_bytes/2010/pb4ch05_ss4

25 In a June 30, 2010 assessment, the Japanese Wind Power Association estimated that 10% of the country’s power could be derived from wind: link.

26 See the data (in Japanese) from the Petroleum Association of Japan.

27 On the “Sunshine Project” and other developments, see this link.

28 For the data, see Matthew Roney, “Solar Power,” Earth Policy Institute, September 21, 2010.

29 On this, see Oshima Kenichi Saiseikanou enerugii no seijikeizaigaku: enerugii seisaku no guriin kaikaku ni mukete [ The Political Economy of Renewable Energy: Towards a Greening of Energy Policy], Tokyo: Toyo Keizai, 2010, pp. 36 and 44.

30 As Gavan McCormack argues in “Japan as a Plutonium Superpower,” Japan can be considered “nuclear obsessed” due to its plan to put plutonium at the centre of its energy economy: link.

31 On the plan, see the July 16, 2010 summary by the METI Energy and Resources Division.

32 The World Nuclear Association’s December 2010 report on “Energy Subsidies and External Costs” shows that Japan’s fission R&D was 61.4% of total energy R&D for 2005: link.

33 On the organization and scale of Japan’s carbon-intensive sector, see Morotomi Toru and Asaoka Mie, The Road to a Low-Carbon Economy [tei-tansoshakai he no michi]: Tokyo: Iwanami, 2010, pp. 16-24.

34 On this matter, see the “Is Japanese industry really the most energy efficient?” section in Kikonet’s “Fact Sheet of the Keidanren Voluntary Action Plan,” no date: link.

35 On the ineffectiveness of voluntary targets, see Kyoto University Professor Ikkatai Seijji’s comments in “Climate Change Policies in Japan,” December 1, 2010: link.

36 An English-language version of the DPJ’s 2009 election “manifesto” can be downloaded here. The environmental policy commitments are on pp 23-26.

37 The previous Aso Taro regime (LDP) had announced a much-derided plan to cut emissions by 8% by 2020 (versus 1990) levels. Japan also has a ridiculously low renewable energy target (as a percent of electrical generation capacity) of 1.63% by 2014. Compare New York state’s target of 24% by 2013 and California’s commitment to 33% by 2020: link.

38 On the studies as well as their politicized use, see Iida Tetsunari and Andrew DeWit “Is Hatoyama Reckless or Realistic: Making the Case for a 25% Cut in Japanese Greenhouse Gases”, Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 7 Issue 38 No. 4 September 21, 2009: link.

39 As former World Bank chief economist Nicholas Stern argues, “It is a profound and dangerous mistake to ignore [green growth] opportunities and see the transition to low-carbon growth as a burden and growth-reducing diversion. That mistake arises if you apply the crude growth models from the middle of the last century with their emphasis on fixed technologies, limited substitution policies, and simplistic accumulation.” See Nicholas Stern “China’s growth, China’s cities, and the new global low-carbon industrial revolution,” November 10, 2010, Policy Paper, Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy: link.

40 “All-Japan” largely means attaching Japanese government loans to overseas project bids as well as making them a top foreign-policy priority. On this see Nippon Keidanren “Promoting Regional Infrastructure Development for a Prosperous Asia,” March 16, 2010: link.

41 The IEA’s 2010 “World Energy Outlook” sees nuclear power as going from 6% of global power production in 2008 to 8% by 2035: link.

42 On these issues, see the summary of the report here.

43 Link.

44 The survey can be found here.

45 On the announcement, see Watanabe Chisaki, “Japan’s Government Fudges Start of Carbon Trading Amid Industry Opposition,” Bloomberg December 28, 2010: link.

46 On Thailand, for example, see Paul Gipe “Thailand Feed-in Tariff Program Harvests Large Crop of Projects,” The Solar Home and Business Journal, December 7, 2010.

47 Note that Denjiren made its organizational bias towards nuclear power clear when it greeted the election of the DPJ in August of 2009 with the following: “For Japan which lacks energy resources, the government must continue to pursue energy policies designed to simultaneously achieve a stable energy supply, economic efficiency and environmental conservation. The key is surely nuclear energy. Therefore, with top priority on safety, we are committed to achieving smooth progress in nuclear power generation, including the nuclear fuel cycle. We expect the new administration to establish solid national strategies and policy frameworks that do not waver in the mid term, as stated in the “Nuclear Power Nation Plan.” (Link)