The Expo Garden and Heterotopia: Staging Shanghai between Postcolonial and (Inter)national Global Power

Samuel Y. Liang

During the six months of World Expo 2010, Shanghai looked exceptionally clean, even spectacular, thanks to the city’s face-lifting projects and a moratorium on construction and factory emissions for the Expo period. After two decades of relentless rebuilding, Shanghai’s cityscape is dominated by clusters of sleek but soulless high-rises, while the city’s major streets accommodate a mix of native and expatriate residents. In contrast to this uninspiring International-style architecture and the city’s heterogeneous street crowds, the Expo site displayed an array of stunning architectural spectacles for the relatively homogenous crowds of predominantly domestic visitors.

The Expo seemed to be an entirely different space from the city; it was presented to the public as shibo yuan or the Expo garden. The garden is a representation of utopia—an idealized recreation of nature, in which mountains, plants, and waters are represented as perfection. Michel Foucault considers this utopian representation of the garden to be heterotopia (or compromised realization of utopia) and the (Oriental) garden to have been a sort of happy, universalizing heterotopia dating from the beginnings of antiquity:

The traditional garden of the Persians was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world, with a space still more sacred than the others that were like an umbilicus, the navel of the world at its center (the basin and water fountain were there); and all the vegetation of the garden was supposed to come together in this space, in this sort of microcosm.…the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection… (Foucault 1986: 25-26)

Shanghai had been weaving an “Oriental rug” since it won the bid to host the Expo. This rug was a recreation of the world in miniature, in which each nation was represented by a pavilion and the navel seemed to be the Chinese National Pavilion—a monument that ostentatiously revived the Middle Kingdom legacy.

The Legacy of Great World Expositions

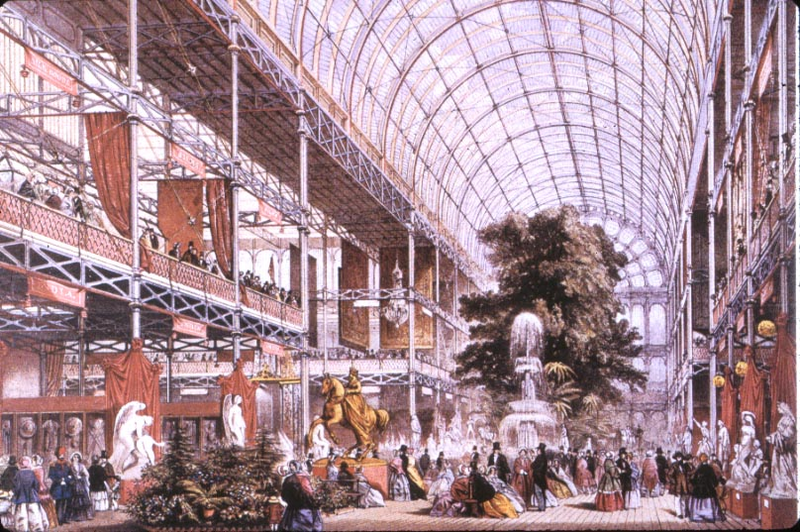

Through their long history, great world expositions were indeed utopian representations, whose main theme shifted between presenting the progress of industrialization and representing distinct cultural spaces from around the world. The first of this kind, the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London, 1851 featured a display of industrial products and machinery in a structure (designed by the gardener Joseph Paxton) that resembled an interior garden and a glass-and-iron “cathedral.” Spectacular images in the exhibition certainly celebrated the capitalist fetishism of commodities, as Marx called it. Such images soon penetrated into everyday lives in the capitalist city via shopping arcades and department stores.

|

The Crystal Palace, Hyde Park, London, 1851 (source). |

The Crystal Palace included exhibits from Britain’s colonies, such as Australia and India. Later world expositions increasingly featured the cultural and architectural spectacles of the colonies; this development reached a zenith in the 1931Great Colonial Exposition in Paris, which displayed the diverse cultures and immense resources of French colonies, especially the indigenous architectural spectacles. The exhibition reduced the colonies to visual images, which the (European) subject gazed at, comprehended, and mastered. This way of mastering the world (or the East) as visual representations may be compared to how the old Oriental garden reduced the world to perfect representations. Whereas the garden was sacred and illusory, the exhibition was secular and “real”—real because the representations assumed the authority of truth.

|

Paris Colonial Exposition 1931 (source). |

Foucault considers certain colonies (such as the Puritan societies that the English had founded in America and Jesuit colonies that were founded in South America in the seventeenth century) to be an extreme kind of heterotopia, not of illusion, but of compensation: “their role is to create a space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled” (Foucault 1986: 27).

Indigenous societies in the colonies, however, were often represented (in Orientalism) as dystopia: a space that is the other, as messy, obscure, and ill-constructed as the West or colonizer societies were not. Yet in the great exhibitions, the representations of colonies and indigenous cultures were idealized or utopian; they had become a measure according to which the Western world was recreated to compensate for imperfections. The practice of representing the colonial world order went beyond the exhibitions, and the city (or the world) became an endless exhibition without an exit (Mitchell 1989).

Colonial Shanghai in the epoch of exhibitions

In the course of the age of the great expositions, Shanghai developed from a trading port to one of the world’s great metropolises. In 1893, the Jubilee of the International Settlement paraded the achievements of the “Model Settlement” that seemed to be more liberal and cosmopolitan than any cities in the West (Goodman 2001; Liang 2010: 169-70). In the next century, the city was built into the “Paris of the Orient” or “New York in the West,” where international power and wealth were displayed, most notably in a cityscape of colonial architecture. The natives called the city “an exhibition of the architecture of ten thousand nations” (wan’guo jianzhu bolan hui), ranging from neoclassical banks and offices on the Bund to Art Deco-style hotels and department stores on Nanking road, and variously styled villas in the French Concession.

|

Shanghai’s “exhibition” of world architecture, Bund, 1930s (source). |

Shanghai’s main-street images were similar to those in the major urban centers of the West, all of which seemed to have been (re)built in the images of the great world expositions. Yet the city’s most native quarters resisted being reduced to legible images; their complexities and opaqueness signaled the Oriental other or dystopia by comparison to the main-street displays. But it was the latter that still inform the current program of rebuilding Shanghai.

Postcolonial Shanghai: negotiating with the past

Since the early 1990s Shanghai has been rebuilding its decayed colonial cityscapes into exhibitory spectacles. While the colonial edifices and villas were restored to their former glamour, the opaque native quarters have been rebuilt into legible but soulless spectacles. This ongoing program reinvents the city’s colonial legacy: not only do the native new rich draw nostalgic connections with the treaty-port era, but a growing population of expatriates is attracted to the city by its colonial heritage, such as the quaint environment of the former French concession. Thus, the city’s new international gloss seems to be quite postcolonial.

The Expo displayed a new world order distinct from the old colonial order. It staged the rise of China as a global power and was ostentatiously a nationalist project whose history can be traced back to revolutionary movements that first emerged in colonial Shanghai. Thus the Expo project seemed to signal a belated “revolution” against the city’s colonial legacy.

In colonial Shanghai, the displays of international power and cosmopolitan cultures—British, French, German, Japanese and American among others—were at once attractive and humiliating for the native residents who comprised the overwhelming majority of the city’s population. The cosmopolitan urban environment nourished liberal and revolutionary thought as well as Chinese nationalism. After the 1949 revolution, the official history of treaty-port Shanghai was written mainly as one of colonial exploitation and national humiliation. Old Shanghai was displayed in museums and textbooks as the evidence of such painful memories. This image was epitomized in a humiliating sign displayed at the Public Park on the Bund: “Dogs and Chinese Not Admitted”—which, according to Robert Bickers and Jeffrey Wasserstrom (1995), was in fact a construct after the end of the colonial era.

The history of old Shanghai was rewritten in the post-Mao era to positively re-evaluate the colonial period. Meanwhile memories of colonial humiliation continued to inspire nationalist narratives that would celebrate the rise of China/Shanghai in a new world order. These two visions of history left marks in the rebuilding of Shanghai. Just as the colonial legacy informed the current redevelopment of transnational Shanghai, nationalist projects occupied the city’s key strategic locations.

The notorious colonial Public Park has been rebuilt into the northern end of a long riverfront promenade, accentuated by the vertical rise of the Monument of the People’s Heroes at the place where Suzhou Creek meets the Huangpu River. But this lonely nationalistic monument looks rather negligible next to the majestic colonial facades on the Bund.

|

The north end of the Bund skyline, with the Monument of the People’s Heroes in the middle right (photo by the author, October 2010). “One Axis and Four Pavilions,” Shanghai Expo 2010 (source). National Pavilion, Shanghai World Expo (Photo by the author in October 2011). The base of Okamoto Tarō’s “Tower of the Sun,” in the Festival Plaza of the 1970 Osaka Expo (source; Minami 2005). |

The former Race Course was rebuilt into the People’s Square in the Maoist era. It turned the colonizer’s “pleasure ground” into a space for mass political rallies celebrating the triumphs of the Party state. In the post-Mao era, this open space was “reclaimed” by the city as a site of civic monuments. Among these monuments, the new municipal administrative building and Shanghai Museum form an axial layout of nationalist grandeur. The museum resembles an ancient Chinese bronze vessel and features a collection of ancient Chinese artifacts that celebrated the national heritage. The City Planning Exhibition Hall next to the municipal building displays the city’s current development schemes. These monuments as the celebration of the new city authority have erased any traces of the Race Course, whose images, preserved in museums and history books, are the evidence of what have been negated. Thus, in Shanghai nationalism seems to be mainly constructed through a negation of the bitter memories of the treaty-port era, of the recent past.

|

Shanghai Municipal Building, People’s Square (photo by the author, April 2011). Shanghai Museum, People’s Square (photo by the author, April 2011). |

The Expo garden as a heterotopia

Like the monuments in the People’s Square, the World Expo seemed to have negated, or have been posited against, the city’s colonial history. The architectural designs of the Expo’s key permanent structures, namely the “one axis and four pavilions,” invoke the axial layout of Chinese imperial complexes and seemingly the ancient cosmology of the center and four cardinal directions. These formed the core of the Expo garden and represented the nave of the world. The Expo then seemed to be a utopia without history.

The Chinese National Pavilion is one of the four permanent pavilions. It has become a new national symbol that apparently has nothing to do with the city’s history. Its iconic images on myriad billboards introduce the national pride into the former colonial quarters. The pavilion’s architecture invokes the image of the “Crown of the East” by recreating the heavenly roofs and intricate wooden brackets of the imperial palaces of the early dynasties. This imperial-style architecture abstracted and reproduced in an enormous scale is an utterly alien form in the city of Shanghai. Viewed from above (when driving across the nearby Lupu bridge) it looked alike a strange square saucer that landed on four sticks, none of which have anything to do with the city’s architectural heritage (in either the colonial or pre-colonial period). For example, the pavilion aims to create a purist architectural symbol of “Chineseness,” seen in its red color and minimalist architectonics, whereas the urban culture and architecture of Shanghai is known for its hybridity and inclusiveness. Ironically, the pavilion’s architectural purism and originality, as the architect claimed, was called into question in an online debate on whether the design was copied from the Japanese Pavilion for World Expo 1992 and other similar structures.

For the bureaucrats and technocrats who selected its architectural design, the National Pavilion fulfilled the function of displaying China’s rise among the international powers. This display was more meaningful to domestic visitors rather than to a handful of foreign visitors. The Expo’s organizer successfully drew huge numbers of domestic visitors each day (sometimes by handing out free tickets) in the effort to achieve a new world record of being the most visited by drawing on the resources of China’s manpower. This “political” target seemed to run against the city’s pragmatic capitalist sprit: the figure overshadowing substance and even profit.

Domestic visitors were not entirely strangers to the idea of “Expo garden.” Many touristy “world parks” have been built in China since the early 1990s, such as Shenzhen’s Window of the World and Beijing’s World Park, which reduce the wonders of the world to miniature models that Chinese tourists can “conquer” in one day. For Chinese visitors the Expo was probably a more authentic version of the world park, as the foreign pavilions are genuine contributions from their respective countries. The Expo served another purpose. The omnipresent native crowds at the Expo showed the world a vast potential market for Chinese consumers/tourists at a time when Chinese tourism is in fact exploding both in China and internationally.

The rather strange architecture of the National Pavilion and the familiar scene of the native crowds in the Expo garden seemed to have envisioned a new world order in which China is a major player. The Expo was rather futuristic and its intrusion into the postcolonial metropolis was meant to signal a (symbolic) reclaiming of Shanghai by the rest of China, a nationalist project that aimed to balance the “re-colonization” of Shanghai by transnational capital.

For the time being, Shanghai remains a cosmopolitan city somewhere between China and the rest of the world. This cosmopolitan urban character has persisted in spite of a number of nationalist construction projects that aimed to reclaim Shanghai from its colonial legacy, such as the Great Shanghai Scheme in the 1930s to today’s Expo. The Expo exhibition is likely to have minimal long-term impact on the city’s development trajectory, especially as the Expo site is rebuilt so as to integrate it into the urban fabric in the coming years. By then the Expo garden will probably be more remembered as being instrumental in the city’s acquisition of a huge quantity of land for redevelopment than as a landmark international or national event.

|

Ando Tadao’s Japanese Pavilion, World Expo 1992 (source). |

The World Exposition as a type of cultural event that brings cultures from around the world together has long passed its prime. It rose in the age of colonial expansion, when the West felt the urge to create an Occidental version of the “Persian garden,” an extreme heterotopia of the colonies, which compensated for the imperfection of the Western world. This Western-centric vision of the world certainly does not work in today’s multi-centered world.

Like Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan’s first World’s Fair, Shanghai Expo staged a reverse or “Oriental” version of the World Exposition. Both events promoted nationalism amidst international and technological spectacles at a time when the respective countries were rising in regional and global terms. But the Shanghai event seemed to be more out of date as the world today is more multi-centered or decentered than in the early 1970s. By reinventing the archaic vision of the world as one nave surrounded by four parts, the Expo was little more than a garden folly, a heterotopia that compensated “imperfections” within the domestic society—such as the growing gap between rich and poor, the squalid quarters of migrant laborers (who built the Expo), and disputes and violent confrontations in the state’s land acquisitions.

Samuel Y. Liang is the author of Mapping Modernity in Shanghai: Space, Gender, and Visual Culture in the Sojourners’ City 1853–98 and is assistant professor of the humanities, Utah Valley University

Recommended citation: Samuel Y. Liang, ‘The Expo Garden and Heterotopia: Staging Shanghai between Postcolonial and (Inter)national Global Power,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 38 No 1, September 19, 2011.

References

Bickers, Robert, and Jeffrey Wasserstrom. 1995. “Shanghai’s ‘Dogs and Chinese Not Admitted’ Sign: Legend, History and Contemporary Symbol.” The China Quarterly, 142: 444-66.

Foucault, Michel. 1986. “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics, 16: 22-27.

Goodman, Bryna. 2000. “Improvisation on Semicolonial Theme, or, How to Read a Celebration of Transnational Urban Community.” Journal of Asian Studies, 59.4: 889-926.

Liang, Samuel Y. 2010. Mapping Modernity in Shanghai: Space, Gender, and Visual Culture in the Sojourners’ City 1853–98. London: Routledge, 2010

Minami Nakawada, ed. 2005. Expo ’70: Kyôkagu: Ôsaka bankoku hakurankai no subete. Daiyamondosha.

Mitchell, Timothy. 1989. “The World as Exhibition.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 31.2: 217-236.