“Lifelong homework”: Chō Takeda Kiyoko’s unofficial diplomacy and postwar Japan-Asia relations*

Vanessa B. Ward

Abstract: This essay addresses the role of individual actors in unofficial diplomacy, and the contributions of non-governmental projects in building international relations in post-WWII Asia. I treat the case of one Christian female as an illustration of the role of progressive intellectuals working outside official circles—a much neglected aspect of Japan’s mid-twentieth century foreign relations.

In March 1974, Chō Takeda Kiyoko (1917–) began a wide-ranging account of her relationship with post-World War II Asia by recalling her receipt of a letter from China in the late 1940s. The letter came from a member of the Chinese Christian Student Movement, whom Takeda had met at the 1948 World Student Christian Federation’s First Asia Leadership Training Conference in Sri Lanka. It expressed the desire that Chinese and Japanese students collaborate to build a new future. Takeda took the letter as a sign of renewed friendship, that their previously amicable exchange based on common loyalty to Christ had not been broken despite the years of disastrous war. It marked, Takeda noted, the beginning of her relationship with postwar Asia.1

In this essay, I examine the nature of Takeda’s engagement with postwar Asia and her commitment to reconciliation between Japanese and Asian peoples as a form of unofficial diplomacy. A variety of terms have been used to refer to the involvement of private individuals and groups in international relations and diplomacy, such as “private diplomacy”, “people-to-people diplomacy” and “people’s diplomacy”.2 Here I employ the more expansive term “unofficial diplomacy” to encapsulate the broad scope of Takeda’s activities aimed at improving mutual understanding between the peoples of Japan and its Asian neighbours. I understand unofficial diplomacy to be the promotion of friendly relations between peoples, independent of nation-states.

Personal contact between foreign nationals can create impressions that differ from those offered by official pronouncements or the mass media. They arguably contribute to a greater degree of mutual understanding and respect between countries and peoples than do official relations, although measuring the influence of unofficial diplomacy is difficult.3 This essay examines the sorts of meetings and encounters through which Takeda contributed to fostering understanding between Japan and its Asian neighbours in the postwar era. After locating Takeda Kiyoko’s unofficial diplomacy in prewar internationalist traditions, I explore her particular approach through an examination of two contrasting encounters in the Philippines. This is followed by a discussion of Takeda’s connections with Chinese Christians and her leadership of a charity for Chinese women and children in the 1980s.

Takeda’s Christian background and career

Takeda converted to Christianity as a young woman of 21 years. She joined Kobe Hirano Church and Kobe YWCA in 1938, a year after enrolling in the senior division of Kobe Jogakuin. At this college for women founded by American missionaries in 1873,4 she was inspired by its headmistress, Dr Charlotte DeForest (the daughter of the American Mission’s representative in Sendai) to continue her education at Kobe Jogakuin’s sister school in the United States, Olivet College. En route to the United States, Takeda travelled to Europe as part of the Japanese delegation to the first international conference of the World Student Christian Federation in Amsterdam in July 1939.

|

The Japanese Delegation to the World Student Christian Federation in Amsterdam (source: Nihon YWCA 100nenshi hensan iikai (ed), Nihon YWCA 100nenshi; josei no jiritsu o motomete 1905-2005, Nihon Kirisutokyō joshi seinenkai, 2005) Takeda Kiyoko with student labour conscripts (source: Deai: sono hito, sono shisō, Kirisutokyō shimbunsha, 2009, p. 65) |

This journey marked the actual start of Takeda’s relationship with Asia. At the ports where the ship stopped off, Takeda developed an insight into to the deep enmity felt towards Japan in Asia and the suffering and devastation caused by imperialism. In Shanghai, Chinese Christians gave the delegates a tour of the so-called “city of death”, which impressed upon Takeda the horror wrought by the Japanese invasion. The misery of colonialism was further reinforced at stop-offs in Saigon, Penang, Singapore, and Columbo, where she noticed the dramatic contrast between the lifestyles of Europeans and locals. What Takeda would later describe as the “unspeakable darkness, poverty, and sadness” of Asia would remain deeply impressed upon her consciousness.5 At the conference, she personally experienced the effect of Japan’s invasion of China when her friendly gestures were rebuffed by the leader of the Chinese delegation, who declared: “If you have any feelings of friendship for us, go back to Japan and do what you can to get those terrible Japanese soldiers out of China!” While Takeda was initially surprised at this admonition, further reflection led her to understand that it was an expression of resentment towards Japan’s presence in China, and she later declared that the task of building friendship between Japan and other Asian countries would become her ‘lifelong homework’.6

After completing her studies at Olivet College in 1941, Takeda attended Columbia University and Union Theological College, before choosing to return to Japan on the last International Red Cross Exchange ship in June 1942. Upon returning to Japan, she was recruited as the director of the Japan YWCA’s Student Section. In this capacity, she mentored Chinese and other foreign “enemy” Christian students and worked alongside Japanese female students conscripted to factory work.7 Still in this role after Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, Takeda represented the Japan YWCA at the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF) First Asian Leadership Training Conference in Sri Lanka in late 1948. She then spent two months in India, during which time she lectured at Madras Christian University and Allahabad Agricultural University, and became acquainted with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, whom she would meet again on his 1957 state visit to Japan.8 In 1953, Takeda resigned from her position with the Japan YWCA to take up an academic post at the newly-established International Christian University (ICU), whence she pursued scholarship on the Japanese encounter with Christianity and led the university’s research programme in Asian cultural studies. ICU was a private institution intended to provide the spiritual and moral foundation for Japan’s regeneration. Its establishment was sponsored by pre-eminent American Protestant missionaries and prominent Japanese educators, and was supported at the top echelon of power in Japan by former statesmen, the Emperor, and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur.9 Appointed as a part-time lecturer, Takeda was soon made a full-time lecturer of intellectual history and educational philosophy, and promoted to assistant professor and then professor before her retirement as professor emeritus in 1988. Takeda’s close association with the University’s first president Yuasa Hachirō, and her acquaintance with members of its American council, likely smoothed the way for her to take leave to travel to China in mid-1956, and to continue her engagement with global ecumenical Christianity. She regularly attended World Council of Church (WCC) international meetings, and served as the WCC’s President for the Asia-Pacific between July 1971 and November 1975.10 In turn, her leadership of the research programme of ICU’s Committee on Asian Cultural Studies (later the Asian Cultural Studies Institute), her promotion of educational links between ICU and overseas universities (including in Asia), and her service on international educational boards and committees, saw her develop a reputation as a respected Christian educationalist. This undoubtedly influenced her positive reception in Asia.11

|

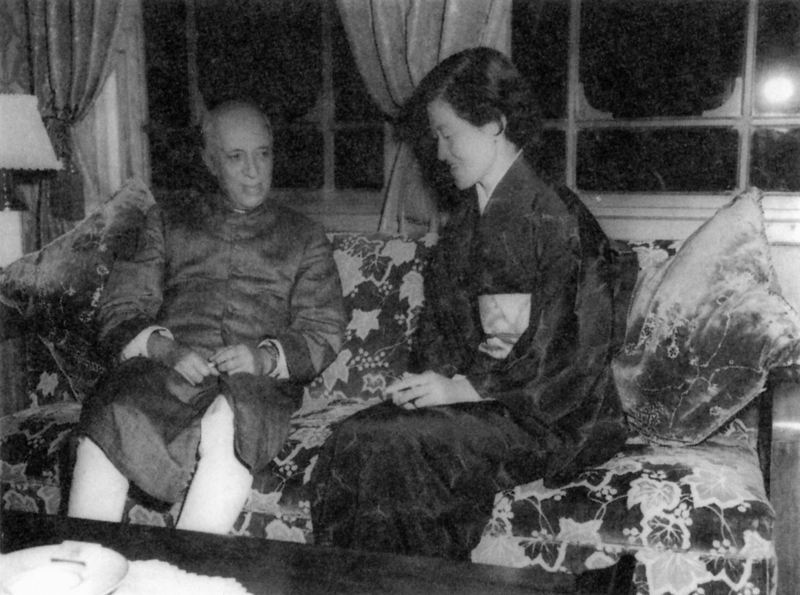

Takeda Kiyoko meets with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1957 (source: Deai: sono hito, sono shisō, Kirisutokyō shimbunsha, 2009, p. 100) |

Takeda’s highly privileged Christian upbringing shaped her personal ethics and informed her worldview. Her exposure to the world through her education and her interactions with intellectual élite from a young age led to a facility with English, cultural competence in non-Japanese environments, and a self-confidence that belied her young age. These factors played important roles in her unofficial diplomacy. Self-assurance gave her the courage of her convictions and allowed her to speak truth to power. Importantly, however, it was tempered by a strong sense of humility and deep sense of justice. This sense of justice underpinned her desire to give something back to disadvantaged Chinese women and girls whose experience of hardship neither she nor her female students at ICU could readily have imagined. Rather than personal remorse for the past deeds of countrymen, her interactions at the grassroots level in Asia reveal a profound sense of injustice at the suffering caused by the sins of flawed humans caught up in the insanity of war.

Lineages and contrasts

In considering Takeda’s engagement with Asia as a form of unofficial diplomacy, it is useful to situate her in the context of two significant lineages of Japanese intellectuals who promoted internationalism. The first comprises famous individuals such as the educationalists Nitobe Inazō (1862–1933) and Uchimura Kanzō (1861–1930), both of whom played an ‘important role in [Japan’s] contacts with other nations’ in the early twentieth century when it ‘had established itself as a respected member of the international community’.12 It also includes members of a subsequent generation who engaged in unofficial diplomacy, men such as Tsurumi Yūsuke (1885–1973) and Yanaihara Tadao (1893–1961).

At the core of these men’s internationalism were Christianity and their close friendships with Americans. Nitobe converted to Christianity as a student, and married an American Quaker. Of his 12 trips overseas, ten were to the United States.13 His friend Uchimura Kanzō was also introduced to Christianity as a student and is most famous for founding the Japanese Christian movement, Mukyōkai. Like Nitobe, he was also deeply impressed by the Quaker faith. Yanaihara Tadao was both a student of Nitobe and a follower of Uchimura in Mukyōkai. The internationalism of Yanaihara’s contemporary Tsurumi Yūsuke was closer to that of Nitobe in that he also had close personal ties with America. Both Tsurumi and Nitobe conducted extensive speaking tours in the United States and sought to promote a more positive image of Japan at a time when public opinion was being mobilised against it. In Tsurumi’s case, this negative public opinion was associated with the 1924 Immigration Act that included Japanese among the Asian races prohibited from migrating to the United States; in Nitobe’s case, it related to Japan’s depredations in Manchuria, especially surrounding the Manchurian Incident in 1931 and the subsequent creation of the puppet-state of Manchukuo.14

The pre-eminent scholar of Japanese Christianity John F. Howes has observed that Christians played an important role in Japan’s international contacts with other nations; they enjoyed a web of relations and were part of a kinship of believers that crossed national boundaries. In the case of Nitobe, Tsurumi and Yanaihara, these networks came together in the Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR), ‘the most significant channel for Japanese-American intellectual exchange before the Pacific War’.15 Nitobe co-founded the Japanese Council of the IPR (JCIPR), and Tsurumi and Yanaihara both contributed to its activities prior to World War II.16

The internationalism of Nitobe, Uchimura, and Tsurumi focussed on the promotion of US-Japan relations. Their strongest ties were with American Christians. By contrast, the historical juncture that Takeda inhabited meant that, while her formative years were profoundly influenced by American Christianity (as discussed above), her most extensive and heart-felt connections were with communities of Asian Christians. She did, nevertheless, support intellectual exchange between the United States and Japan, and was one of only two Japanese female members of the postwar American-Japan Committee for Intellectual Exchange. To the extent that this committee offered a forum to restore U.S.-Japanese relations outside of the constraints of formal diplomacy and government policy, it could be likened to the pre-war JCIPR. Indeed, the Committee could be said to have inherited the legacy of prewar internationalism, and one of its central members was Takagi Yasaka, a student of Nitobe.17 Underpinning Takeda’s involvement with the postwar Committee was not so much the desire to promote friendly sentiment towards Japan in the United States as Nitobe and Tsurumi had attempted in the 1920s and 1930s, but rather to facilitate constructive conversation between the two countries for the promotion of world peace in the post-World War Two era.18

Takeda is part of another important lineage: three generations of Japanese women associated with two transnational Christian women’s organisations: the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the World Young Women’s Christian Association. These organisations embraced the notion that women are worthy ‘civic beings [and] participants in shaping the conditions of their own lives and the life of the body politic’,19 and thus, their activism might be considered a precursor to the international feminism of the postwar period. In her role as a student leader with the Young Women’s Christian Association, her involvement in World Student Christian Federation activities in the Asian region, and her tenure as a President for the Asia-Pacific of the World Council of Churches (WCC), Takeda was at the centre of the global ecumenical network, and deeply committed to its outreach activities in the service of women’s advancement and world peace. The scholarship on Japanese women’s involvement in these ecumenical networks has focussed on the transnational links it afforded, particularly for American and Japanese women, and has not treated the networks that connect Japanese with other Asian Christians.20

Takeda’s engagement with Asia was inspired more by humanist than political concerns. Direct engagement with formal politics required more time than she was prepared to dedicate; and she was more interested in pursuing scholarship.21 While not uninterested in the formal relations between nation-states, she deliberately avoided too close an association with the Japanese state and its policies. This did not mean that she lacked interest in political questions. Indeed, many of the issues that she engaged with indirectly through her writings or through her support of particular organisations were political in nature. However, Takeda’s low-key involvement with politically-sensitive issues reveals her disinclination to engage directly with official diplomacy, foreign policy and international relations.22 While she had ties with many of the organisations established for the purpose of promoting relations between Japan and the United States, she was not involved in any formal or informal lobby groups seeking to influence foreign policy.23 Moreover, she did not mobilise her contacts among Japan’s business and political élite to influence Japan’s diplomatic relations, but rather, as the discussion below of the Sōkeirei Japan Fund shows, did so in order to generate financial and material support for a charity aiming to improve relations between Japan and China.

Takeda’s approach to formal politics can be contrasted with contemporary male intellectuals such as Tsurumi Shunsuke and other leaders of the Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam, who took to the streets to press their cause in the late 1960s, and Ichikawa Fusae (1893-1981), the leader of the women’s suffrage movement and a long-term member of the House of Councillors. While an ardent supporter of peace in Southeast Asia, and the elevation of women’s status and the development of their political knowledge, Takeda never expressed her support for these causes by joining public protests. Although she did not share Ichikawa’s methods, Takeda acknowledged her dedication to improving women’s status when she insisted that Ichikawa be sent as a representative of Japanese women to the United States by the American-Japan Committee for Intellectual Exchange,24 and has expressed her profound respect for Ichikawa in numerous publications.25 Like Ichikawa, Takeda also pursued positive international relations through unofficial diplomacy, principally through involvement in transnational fora and their search for a constructive balance between internationalism and nationalism.26

While the state and formal politics did not dominate Takeda’s meetings with other Asian Christians, a sense of national identity was certainly present. Takeda identified strongly as a Japanese. In June 1942, she was given the choice to continue her studies in New York, when her mentor Reinhold Niebuhr and his wife offered to act as her guarantors. However, as the last International Red Cross Exchange Ship was preparing to depart from New York, she chose to return to Japan as she did not feel entitled, as a Japanese, to avoid the devastation that she knew was to come.27 Moreover, Takeda’s encounter with Chinese students in Amsterdam in 1939 showed that neither side could easily dispense with their affiliation to a nation-state. And, as discussed below, in the Philippines, Takeda’s identification as Japanese led her to assume responsibility and express remorse for past injustices committed in the name of the Japanese state. At the core of her engagement in Asia was the moral responsibility she felt both as a Christian and a Japanese.28

In the Philippines

Two episodes suggest the impact that Takeda had on shaping attitudes towards Japan in the Philippines. They illustrate the different forms her unofficial diplomacy efforts took, and the potency of unofficial diplomacy in different situations. The first, where she engaged with ordinary people, reveals the role of humility and patience, of listening and hearing, in healing the wounds of war. The second, an audience with a pre-eminent statesman, illustrates the powerful impact of frank exchange on sensitive issues. In both instances, Takeda’s position as a representative of a global Christian organisation—in the first, the YWCA and in the second, the WCC—was an enabling factor, providing not only the opportunity for dialogue, but also her credibility as a participant in it.

In 1951, a chance encounter demonstrated that true understanding between peoples is the foundation for reconciliation. On the way back to Japan from WSCF and WCC meetings in Europe, engine difficulties forced the aircraft on which Takeda was travelling to land in Manila. Japanese passengers—unable to obtain visas as diplomatic relations had yet to be restored between Japan and the Philippines—were confined to a hotel for the week that the repairs would take. Learning that there were Christians among them, some local faithful took Takeda into their care. She was led around many homes, and told story after story of the violence of Japanese soldiers. She was dumbstruck when asked why the Japanese were such cruel people. Her humility and forbearance were acknowledged when she was told, “It is not easy to live with hate. We will not repeat these stories anymore”—words that she interpreted as a type of forgiveness. She was also taken to visit Japanese prisoners of war at the New Bilibid Prison, Muntinlupa City, where she was entrusted with a package of letters by a Japanese internee, which she was pleased to be able to deliver to his family in Japan.29

In 1951 when these events took place, the Philippines-Japan relationship was complicated both by tensions over the treatment of war criminals and by relations with the United States. The Philippines government disagreed with the American stance on war reparations. Washington argued that reparations would have a deleterious impact on Japanese economic recovery. Manila insisted that compensation was due for the particularly harsh damage inflicted by the Japanese invasion. While the Philippines became fully independent in July 1946, it remained closely tied to its former colonial master and was wary of risking the future of the new republic, which relied on special access to the United States market and continued American investment.30 President Quirino (1948–1953) thus trod a tight-rope between cooperation with the American position on war reparations, which elicited ‘important tokens of recognition’ of Philippines independence,31 and standing firm on his new nation’s demand that Japan compensate the Philippines for the material and psychological damage inflicted during the war. The Philippine government made a formal reservation to the San Francisco Peace Treaty, declaring it would negotiate a reparations agreement notwithstanding ‘any provision of the present treaty to the contrary’.32 Diplomatic negotiations between the governments of Japan and the Philippines were opened in 1952, the last Japanese imprisoned for war crimes in the Philippines were repatriated in 1953, and diplomatic relations were fully restored after ratification of a separate bilateral reparations agreement in July 1956.

In September 1974, Takeda returned to the Philippines and met a very different Filipino to those she had interacted with two decades earlier. She was the WCC’s representative on a delegation of the Christian Conference of Asia that was lobbying for the release of prisoners of conscience, among them two of its own Manila-based staff members. The delegation eventually succeeded in securing an audience with President Ferdinand Marcos. Ron O’Grady led the delegation and his powerful description of the meeting deserves quotation in full:

We were kept waiting some time of course and finally were ushered in through the long corridors of Malacanang Palace to see the great man. We arrived at his very large private office and waited some more. His desk was on a raised platform and we sat below it facing each other so we had to turn slightly and stretch our neck to see him.

He walked in, we stood up and walked to the platform to reach up and shake his hand. When we were seated he began. “I know why you are here….” and there followed the most boring lecture on the need for the church to support him and not be like those terrible liberation theology people in Latin America. He had a Jesuit friend who advised him on all matters and etc etc.

After about 30 minutes of this lecture he got on to his wartime experiences. By this time we were all desperate and ready to give up. But then as he was talking about his and everyone else suffering during the war a magical thing happened. Ms Cho [Takeda] quietly stood up and interrupted him. She said to him. “Was that us, Sir?” Marcos was taken aback – “well er yes Madam, yes, yes it was Japanese soldiers”. Ms Cho then did what Japanese can do so beautifully – she made confession of guilt and asked for the President’s forgiveness for the suffering that had been caused. It was a very moving moment.

Marcos I believe was genuinely touched and from that moment the meeting took a different turn. We received no promises but the discussion ended on a reasonably cordial note. Marcos gave us a signed copy of his latest book and we all went home. Soon after, [X] was released and [Y] was allowed to leave but not to return.33

In this episode, Takeda’s genuine expression of remorse had a very practical immediate result: the release of Christian Conference of Asia staff. Takeda had succeeded in disarming the Filipino President in the middle of his expression of hostility towards Japanese. Her representation of herself as Japanese gave legitimacy to her apology, but rather than an assertion of national identity, it should be seen as a tactical guise, and an expression of her Christian humility. No doubt the President’s own Christian faith—he was a Roman Catholic—also gave her credibility, as it would have the delegation as a whole. The Christian Church had long been a potent socio-political force in the Philippines, and Christians constituted an overwhelming proportion of the population.34 Marcos was keenly aware of the important influence of the Christian churches in politics, and no doubt wary of their potential threat to martial law. Both the Roman Catholic Church, the largest religious institution in the Philippines, and the Protestant Church were key players in Philippines politics because of their vast networks and resources. Marcos’ contempt for liberation theology—a feature of the churches’ activism in the 1970s that would had a profound impact on young seminarians, students and church leadership—is further suggestive of his appreciation of the Christian Church’s influence on public opinion, the Filipino electorate, and key institutions that affected policy and political decisions. Marcos certainly acknowledged the significant political influence of indigenous Christian churches, giving his full support to the Iglesia ni Cristo, and ‘helping [to] expand its membership and paying regular visits its leadership’; in turn, ‘it supported Marcos throughout its regime’.35

|

(Takeda Kiyoko, World Council of Churches President for the Asia-Pacific (source: World Council of Churches) |

Marcos may also have been mindful of the importance to the Philippines of maintaining good relations with Japan. Filipino-Japan relations had grown strongly in the previous decade. Economic ties, in particular, had developed steadily. By 1960, the Philippines was Japan’s second largest market, and in 1971 Japan became the largest consumer of Philippine exports. Four years later, Japan would displace the United States as the main source of investment in the country. In 1973, a Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation was ratified in advance of a state visit to Manila by Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei.

In the Philippines, Takeda was recognised as a legitimate actor because of her identity as both a Christian and Japanese; in one instance, her Christianity inspired confidence while her national identity was the object of the local people’s resentment and their motivation to engage with her; in the other instance, her representation of a global Christian ecumenical organisation provided the opportunity to intercede on behalf of other Christians while her national identity constituted a useful tool for achieving the intended outcome. While Takeda identified as both a Christian and a Japanese, her commitment to humanity stemming from her faith always took precedence over her concern with national identity. Her apology on this occasion was not intended to be on behalf of the Japanese state, but an expression of her humanist interest in better relations between Asian peoples.

If Takeda’s intervention in the Christian Conference of Asia’s meeting with President Marcos saw her strategically seize an opportune moment, she was also committed to the gradual process of building goodwill between Japan and its former enemies, and the long-term task of achieving reconciliation through dialogue. The complexity of this task was especially apparent in the case of relations between China and Japan.

In China

Takeda’s unofficial diplomacy vis-à-vis China took two forms. One was contact with Christian circles and networks in the early years of Communist rule. The other was her support for the charitable organisation Sōkeirei [Soong Ching Ling] Japan Fund, for which she served as director between 1984 and 2000.36

The first contact that the Student Section of Japan YWCA had with postwar Asia was in the form of the letter that Takeda received from China in the late 1940s. In the letter, Chinese students wrote: ‘Even in the midst of the war devastation, we kept our promise and observed a day of prayer for Japanese and Chinese students. Let’s continue to work together’.37 In comparison, Korean Christian students were less receptive towards contact with their Japanese counterparts. Takeda recognised in the early 1950s that engagement with them depended upon genuine reconciliation between the two countries, and Korean acceptance of a Japanese apology. The contrasting attitudes of these Chinese and Korean Christian students towards Japanese Christian students in the early postwar era illustrates the significance of different experiences of Japanese imperialism, and different trajectories of the nationalist struggles in China and Korea.

The Chinese and Korean Christian movements had endured interference under occupation by the Japanese state, which strongly affected their attitudes to the Japan YWCA and YMCA. In the case of Korea, close to one-half century of Japanese colonialism fostered a deep-seated resentment to Japanese nationals, and inspired an independence movement in which Christian nationalists had played significant roles. This led to a close association between Korean national identity, Christian faith, and anti-Japanese sentiment. This sentiment lingered on into the postwar era and, as a result, reconciliation between Japanese and Korean Christian students was late in coming.38 In the case of China, the shorter duration of Japanese occupation had, according to some assessments, the positive effect of promoting unity between Christian churches and further fostering the spirit of independence from foreign missions.39 It may also have steeled the resolve of Christian leaders and equipped them to negotiate relations with the Communist state.

An important background factor to the strength of Protestant Christianity in the early days of Communist rule was the legacy of the prominence of Christians in élite circles in the preceding half century. In the final years of the Qing dynasty and in republican China, close collaboration between educated Chinese Christians associated with organisations such as the YMCA that engaged in social welfare work, and the political and social establishment led to the YMCA and the YWCA being ‘integral parts of the Sino-Foreign Protestant establishment’ and ‘leading Christian statesmen in government service [and] prominent Christian intellectuals and academics [being] members of or closely cooperated with the Ys’.40 The political climate was essentially favourable towards Christianity, however personal networks also played an important part in its influence. In the top echelons of the nationalist government there were powerful figures such as Kong Xiangxi, a ‘staunch Christian believer and supporter of Christian causes’,41 whose marriage to Song Ailing, the sister of the wives of two powerful leaders, Sun Yatsen and Chiang Kaishek, brought him ministerial posts. As in Japan, Chinese Christians also sponsored the unofficial diplomacy of the Institute of Pacific Relations: Yu Rizhang (1882–1936), a ‘quintessential example of the importance of the YMCA under the Republic’, was a founding chairman of the Institute of Pacific Relations.42

The YMCA maintained some influence in Communist China. The leadership of Wu Yaozong, the National Student Secretary of the YMCA, of the so-called “Three Self Patriotic Movement” (TSPM) is said to have ensured the church’s survival.43 The TSPM was a pro-government structure into which the Protestant churches were merged in 1954; its governing committee comprised Christians who had been active in the YMCA and YWCA in the 1930s and 1940s, and progressive Christians who ‘sympathised with the CCP objectives of social reform and national independence’.44 Perhaps because of their apparent support for the Communists, Chinese Protestants were treated leniently in the early days of the People’s Republic, however the TSPM would eventually fall victim to the suppression of Christianity and the churches in the Cultural Revolution.

Takeda’s desire to renew relations with Chinese and other Asian Christians was shaped by the opportunity for travel in postwar Asia afforded by her position as Director of the Japan YWCA’s Student Section. Travel led not only to incidental meetings such as the one with local people in Manila described above, but also to arranged meetings with young Asian Christians, many of whom would go on to hold significant positions of authority. The 1948 World Student Christian Federation’s First Asia Leadership Training Conference in Sri Lanka—Takeda’s first time out of Japan after the war45—was an opportunity to meet up with acquaintances made at the Amsterdam Conference nine years earlier, and further impressed upon Takeda the possibilities for peace and reconciliation afforded by Christian fellowship. She was taken aback by the generosity towards her as a Japanese, and impressed when the group expressed its hope for a new departure for Asia based on true reconciliation. She would later relate her discomfort at being forgiven—she remembered most vividly being warmly greeted by the Filipino delegate and later president of Silliman University who ‘said, “I had forgiven you before I saw you”’46—and reflect on her then immature grasp of her own war responsibility as a Japanese, as well as her keen awareness of the struggle the Korean delegates faced with having to sit and talk with a Japanese.47 From Sri Lanka, Takeda travelled to India, returning to Japan in March 1949. These travels, she would later recall, were crucial in shaping her thoughts about postwar Asia; they provided valuable new perspectives on issues such as where she, as a Japanese Christian, fitted into Asia. They also led to important and varied experiences and encounters, all of which constituted valuable opportunities for the exchange of views and fostering greater mutual understanding.

The relationship between personal experience and mutual understanding is illustrated by Takeda’s early postwar contact with Chinese Christians. The first such contact took place during an unavoidably extended stop-off in Shanghai en route to Sri Lanka in late 1948.48 As Communist forces advanced on the city, Takeda was struck by the resolve and initiative of Christian university students and local citizens who were determined to embrace the revolutionary spirit that was spreading through their country. She understood their response to her admission of Japan’s war responsibility—that ‘all of Asia has suffered from imperialism’—as a declaration that the unfolding revolution in China had significance for political reform across Asia. Reflecting on the importance of this conversation, Takeda noted: ‘I had had a very strong interest in social revolution at the time, and for me personally, this opened up a completely new bond of mutual understanding’.49

It would be several years before Takeda was able to explore this bond. The opportunity came with the “hundred flower movement”, when, in the spring of 1956, an invitation from a Chinese Christian led to a month-long visit to the PRC. During this time, Takeda travelled extensively throughout China, meeting with Christians in Shenzhen, Guangdong, Shanghai, Beijing, Wuhan and Nanjing, and Hong Kong. She was able to renew her close association with Ting Kuang-hsun, the then leader of the TSPM and principal of Nanjing Union Theological Seminary, who travelled from Nanjing to meet her in Shanghai.50 This association undoubtedly smoothed the way for meetings with other Christians in China’s major centres. Among the many prominent people whom Takeda met on this occasion was Xu Guangping (1898–1968), a prominent figure in Chinese women’s organizations and head of the Chinese People’s Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries.51

|

Figure 5: Takeda Kiyoko with Ting Kuang-hsun and his wife, 1956 (source Deai: sono hito, sono shisō, Kirisutokyō shimbunsha, 2009, p. 143) |

This visit was an early example of the extensive de facto relations between the People’s Republic of China and Japan that were pursued prior to normalisation of diplomatic relations in 1972.52 This contact was mainly through trade, but there were also official cultural and political missions. The official status of this contact was crucial as private travel for non-official or leisure purposes was not permitted to ordinary Japanese until 1964. In that year, one commentator noted that Japan had ‘had more varied and extensive contact with the Chinese communists since the mid-1950’s than any other non-Communist nation, despite the absence of official ties’.53 Close political and security relations and full and open diplomatic engagement during the Cold War era were impossible due to Japan and China’s incorporation into the mutually antagonistic alliance system (Japan with the United States and China with the Soviet Union), and the Sino-Japanese relationship developed on the basis of informal contact, particularly in the area of trade.54 Continuous growth in bilateral trade led to an interdependence that promoted relations in other areas and ensured that political tensions such as those caused by the accentuation of ties with the United States under Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke (1958–1960) did not develop into complete rupture.55 The Chinese state encouraged unofficial contact, courting ‘sympathetic politicians and businessmen’,56 and tacitly promoted informal bilateral connections and cultural exchange through its policy of “people’s diplomacy”.57

Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations were considered to have been ‘normalised’ with the signing of the ‘Joint Communiqué of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People’s Republic of China’ in September 1972, when Japan declared itself ‘keenly conscious of the responsibility for the serious damage that Japan caused in the past to the Chinese people’. In August 1978, China and Japan confirmed in a Treaty of Peace and Friendship that the Joint Communiqué constituted ‘the basis of the relations of peace and friendship’ and further endeavoured to ‘develop economic and cultural relations’ and ‘promote exchanges between the peoples of two countries’.58

Commenting two months after the signing of the Joint Communiqué, Takeda described normalisation as ‘long-anticipated by the Japanese people’, although she clearly understood that the Communiqué statement was no panacea for the problems attending the Sino-Japanese relationship.59 Reflecting on the tendency in Japanese views of foreign countries and Japanese foreign relations towards subjective and ideological generalisation,60 Takeda expressed her hope that the normalisation of Sino-Japanese relations not be treated too emotionally, lest emotion distort the development of the relationship. With normalisation, her thoughts turned to the important question of cooperation between Japan, China, the United States and the Soviet Union for “peace in the Pacific”. Sino-Japanese normalisation was, she observed, the first step towards shared responsibility for ensuring this peace. She further opined that ‘cooperation and mutual restraint of these powers in their joint search for the best way forward for the independent cultural, political and economic development of weaker Asian countries, was fundamental to securing “peace in the Pacific”’. It was essential that Japan pursue relations with China and every other neighbouring Asian country, having first faced up to its past aggression towards these countries and admitted its war responsibility. Similarly, it was the Japanese people’s duty towards humanity to strive for “peace in the Pacific” even after the normalisation of Sino-Japanese relations.61

Takeda’s hopes were not to be realised. From the 1980s, the Sino-Japanese relationship was beset by a string of incidents related to Japan’s military aggression towards China in the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, the weight of the past led to use of the epithet “the history problem” to refer to the unresolved issues linked to Japanese aggression in China. One-sided descriptions of events in Japanese history textbooks, periodic gaffes by Japanese politicians in statements on the war, and official visits to the Yasukuni Shrine (where the souls of Japanese soldiers are enshrined) were taken by China as a sign of the doubtful sincerity of Japan’s war apologies and revived painful memories.62 While the Chinese side has insisted that true friendship and constructive bilateral relations can only exist if the nature of past events is sincerely acknowledged, the posture of the Japanese state suggested that its position was that relations should proceed on the basis that the past had been resolved.63

Cultural exchange has been a constant feature of the Sino-Japanese relationship, although perhaps one of the least studied.64 The potential for the behaviour of non-state actors such as revisionist historians and neo-nationalist ideologues, especially in regards to Japan’s war record, to spill over into the formal political level has been abundantly clear in the past two decades, as demonstrated by ongoing tension over the representation in Japanese history textbooks of Japan’s wartime aggression in China. Such issues are often amplified by a news media that thrive on the ensuing controversy. The reverse process is also evident, however: unofficial cooperation between Japanese and Chinese citizens is often inspired by a perceived need to counteract the damaging impact on cultural understanding of clumsy officials and the Japanese state’s recalcitrance on communicating a sincere and full apology for its wartime record. Such efforts, however, tend to suffer from the lack of attention given to the unofficial diplomacy of non-state actors such as Takeda or unofficial cooperation in international media.

While such projects of unofficial cooperation are beset with difficulties, their incremental contribution to information exchange and the maintenance of channels of communication is invaluable. Cultural exchange, such as the collaboration of Chinese, Korean and Japanese historians on the production of a middle-school history textbook in the first decade of the twenty-first century, has demonstrated the willingness of some sections of Japanese society to counter the direction of official policy.65 Such unofficial efforts may be welcomed for what they are; however, they ultimately fall short of assuaging Chinese anger if official efforts are not also forthcoming.66

Informed citizens and civil society groups have also organised to strengthen the path to reconciliation by working towards mutual understanding, trust and goodwill between the peoples of Japan and China with a view to enduring peace.67 One such group, the Sōkeirei Japan Fund, looked back to a missed opportunity in an earlier era of Sino-Japanese relations. It was established in September 1984 in response to a request from a Chinese foundation the goal of which was to continue the charitable work of Soong Ching Ling (1893–1981).68 Soong Ching Ling was a celebrated figure in the history of the People’s Republic of China. She was named an Honorary President of the country in 1982, and the China Soong Ching Ling Foundation had close links with the Chinese state.69 Takeda served as the director of the Sōkeirei Japan Fund (hereafter referred to as SJF) until 2000, when it was dissolved.70

According to the SJF’s former general manager, the respect in which Takeda was widely held and her extensive acquaintances in élite economic and political circles were instrumental in securing not only the financial support of prominent businesses but also official funds from the Japanese government.71 Indeed, Takeda’s reputation persuaded officials to acquiesce to her courageous unscheduled visits to various Ministries to speak with senior bureaucrats.72 It also led to several high profile individuals serving on the SJF’s board of directors, which in turn attracted increased sponsorship, further facilitating its work. During Takeda’s tenure as director of the board, the SJF received close to 500 million yen in official ODA funds for its projects.73 These funds, along with donations from companies and the general public were channelled into the provision of scientific technologies and the modernisation of infant educational and maternal health facilities in China. A particular focus was on enhancing the facilities planned by Soong Ching Ling herself, such as a children’s science park in Beijing.74 In its second decade, the SJF focussed its efforts on support for education in mountainous agricultural regions, in cooperation with the China Soong Ching Ling Fund’s campaign to ameliorate poverty in remote areas of China. In this period, it co-ordinated the material and financial support of Tokyo Lion’s Rotary Clubs for the construction of primary schools in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, and the collection of public donations for classroom materials, scholarships for the post-primary education of girls, female teacher training, and literacy classes for adult women in Ningxia.

The Fund’s focus on practical assistance at the grassroots level ensured that the organisation did not become mired in the political complications or ideological rifts that attended the formal Sino-Japanese relationship and Takeda’s apolitical stance facilitated broad cross-party support for the SJF.75 The SJF also endeavoured to deepen its members’ understanding of contemporary Chinese society. In the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Gate Incident, Takeda promoted understanding of the underlying causes of the incident through discussion of the nature of democracy in China by bringing together scholars and China experts for regular study sessions with SJF members.76 The members’ awareness of China was not to be limited to theoretical knowledge, however; regular tours to China to observe first-hand the progress of SJF-sponsored projects were organised to inform them of the situations faced by local Chinese. These tours provided the opportunity for direct contact and frank exchange with ordinary Chinese people. Such initiatives illustrate one of the foundational principles of the SJF: that mutual understanding based on knowledge and experience, and its practical expression, can lead to improved relations between peoples and contribute to world peace. They also demonstrate Takeda’s understanding of peace-building—that it was the result of not only the will and initiative of officials and government leaders but also grassroots sentiment that depended social and economic justice—and her willingness to engage at both levels.

Takeda’s contribution to welfare work in China was recognised by the Chinese government with an honourable mention in December 1994, and with an invitation, issued through the China Soong Ching Ling Foundation, to attend the 50th anniversary commemoration ceremony of the founding of the Peoples Republic of China. Takeda’s own account of the establishment of the SJF notes that it reflected the deep respect of Japanese and their feelings of friendship towards Sun Yat-sen and Soong Ching Ling.77 According to both this account and the testimony of the former SJF manager, the SJF also represented a practical expression of atonement for the failure of Japanese to respond to Soong Ching Ling’s call to Japan to support China’s fight against Western imperialism, and to atone for Japan’s subsequent aggression in China.78 Japanese had caused so much destruction and loss of life in China in the past; now they would support its children, its future.

Towards a Conclusion

Personal experience of other places and contact with other peoples, an understanding of history and the political circumstances of countries, and an insight into the future aspirations of peoples, were all crucial elements of Takeda’s unofficial diplomacy. The sense of mutual respect and understanding that grew from honest communication with others was at the core of her personal encounters in early postwar Asia. In the Philippines, her humble expression of apology on behalf of the Japanese people was reciprocated with an expression of forgiveness. The low-key nature of Takeda’s meeting with ordinary Filipinos enabled a glimpse of genuine reconciliation at a time when formal relations between the Philippines and Japan were complicated by global power politics. Before the restoration of official Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations, Takeda’s involvement in Christian networks gave her the opportunity to resume the friendship between Chinese and Japanese Christian communities. From the 1980s, the focus of Takeda’s unofficial diplomacy was on practical assistance towards another section of the Chinese population, disadvantaged women and children. Practical assistance may be interpreted as a tangible aspect of reconciliation, compensation for harm caused by Japan’s wartime aggression and belated restitution of justice.

Takeda’s unofficial diplomacy did not end when she returned from her travels. She continually reported on her experiences upon returning to Japan; her many articles in major newspapers, prominent intellectual journals, popular women’s magazines, and Christian periodicals related political conditions in Asia and the situation of other Asian peoples. This was important information on places and issues that received little attention in the mass media. Through these accounts, Takeda contributed to widening the knowledge of Japan’s neighbours among ordinary Japanese, providing the basis for improved understanding and for better relations.79

To what extent, if any, Takeda influenced Japanese public opinion or official Japanese foreign relations is uncertain. She undoubtedly shaped the level of knowledge and opinion of Asia in sections of Japanese élite circles, and sentiment towards Japanese, albeit perhaps only temporarily, in a small section of the Filipino population. Her impact on Asian statesmen is also beyond doubt, as the examples discussed above show. Takeda was successful in achieving the desired outcome in the meeting with President Marcos, and her leadership of the SFJ contributed to alleviating the daily burdens and improving maternal and child education and health in remote Chinese communities. In other cases involving less determinate purposes the nature of her influence on official relations is difficult, even perhaps impossible, to measure.

Regardless of influence, Takeda certainly demonstrated by example the value of transnational personal networks and the contribution of private individuals committed to universal human values and mindful of the past, to the reparation of relations and possible reconciliation between peoples once divided by war. Her commitment to building ties between Japanese and other Asian peoples in the post-WWII era was underpinned by continuous engagement with individuals and community groups from other Asian countries from the late 1930s. It was based on an informed appreciation of the impact of Japanese imperialism in Asia and the pain and enduring suffering inflicted by war. She pursued goodwill by working through existing Asian ecumenical networks—networks that facilitated constructive encounters, leading to degrees of mutual understanding and, arguably, improved relations between the peoples of Japan and Asia.

The examples of Takeda’s engagement in unofficial diplomacy introduced here illustrate the broad scope and varied nature that transnational actors’ involvement in world politics take, as well as its varied efficacy. They demonstrate various dimensions in terms of structure (degrees of formality), recognition (as a representative of a specific institution or less determinate), and purpose (immediate or gradual).80 In terms of structure, Takeda’s interactions ranged from incidental encounters at the grassroots and low-key engagement with local and disadvantaged communities, to planned, formal meetings with leading statesmen. This scope was mirrored in the dimension of purpose, which ranged from the gradual and evolving process of relationship- and trust-building, to the narrower objective of securing a definite, specific outcome. Takeda’s ultimate purpose, however, has been consistent—to build better relations between peoples and world peace—she simply adapted her pursuit of this according to the particular circumstances she has faced.

In these different circumstances, Takeda’s personal qualities were also variously apparent: in one instance, she was a compassionate witness and a patient and empathetic listener; in another, she was a strategic thinker and deliberate actor. In terms of recognition and its inverse, representation, Takeda has been sensitive to her identification as a Japanese Christian, and the various responses this has prompted, stressing either her national identity or her religious faith according to her particular purpose and the conditions of interaction. In different instances, ordinary citizens and senior officials alike recognised her as a legitimate and credible partner in dialogue, not only because of her identity as a Japanese Christian but also because of her association with trusted entities: the Japanese branch of a transnational Christian youth movement, an international Christian university, a global Christian ecumenical organisation, and a Japanese charity associated with a familiar and respected institution. If, in official diplomacy, recognition of a state by another state is the ‘holy grail of legitimacy’,81 it also underpins the mutual trust that is at the core unofficial diplomacy.

International relations scholars have paid considerable attention to the ascendant role and practices of transnational non-state actors in international relations82 and there is an emerging corpus of literature on gender and transnational organisations.83 However, there is as yet little scholarship focussed on the contributions of individuals to unofficial diplomacy and the importance of personal experience and interaction in this process. These are the aspects of unofficial diplomacy that are harder to document. Takeda’s case demonstrates the potential impact on bilateral relations of motivated individuals with strength of conviction and personality who are neither agents nor instruments of states, and points to the need for further scholarly attention to the ideational and social structure of international relations.

Vanessa B. Ward specialises teaches modern Japanese history at the University of Otago. Her research centers on post-WWII Japanese intellectual life and publishing culture. She is an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

Recommended citation: Vanessa B. Ward, “‘Lifelong homework’: Chō Takeda Kiyoko’s unofficial diplomacy and postwar Japan-Asia relations,” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 30 No 3, July 25, 2011.

Articles on Related Subjects

•Murakami Haruki, Speaking as an Unrealistic Dreamer

•Philip Seaton, Historiography and Japanese War Nationalism: Testimony in Sensōron, Sensōron as Testimony http://japanfocus.org/-Philip-Seaton/3397

•Hankyoreh and William Underwood, Recent Developments in Korean-Japanese Historical Reconciliation

•John Breen, Popes, Bishops and War Criminals: reflections on Catholics and Yasukuni in post-war Japan

•Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War

•Yoshiko Nozaki and Mark Selden, Japanese Textbook Controversies, Nationalism, and Historical Memory: Intra- and Inter-national Conflicts

Notes

* Chō is Takeda Kiyoko’s married surname. After her marriage, she continued to use her maiden name, and thus in this essay I refer to her as Takeda. This essay is part of a larger study of Takeda’s intellectual and scholarly activities, that situates her rich and engaged life in an alternative narrative of twentieth-century Japanese intellectual life. (See Vanessa B. Ward, ‘Takeda Kiyoko: A Twentieth-Century Japanese Christian Intellectual, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 10:2 (December 2008), pp. 70-92). I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Takeda for her continuing support for this project, and to her son and daughter-in-law, with whom she resided in 2009–2010, for their generosity in facilitating our meetings.

1 Takeda Kiyoko, ‘Watashi no naka no “Ajia”’ [My “Asia”], Sekai 340 (March 1974), pp. 270-276, p. 271.

2 The Japanese term most commonly used, “minkan gaikō” [private diplomacy], points to the engagement of non-state actors in unofficial relations between countries, with or without official encouragement. This sort of engagement constitutes a low-key means for Japanese private companies and businesses to support charitable projects and the work of Japanese non-governmental organisations abroad. I understand unofficial diplomacy as the promotion of friendly relations between peoples, independent of nation-states. It may be distinguished from the terms “people-to-people diplomacy” and “people’s diplomacy” [kokumin gaikō], which by contrast, are more closely associated with national identity, and often used to describe the Chinese state’s policy of sponsoring friendship groups, cultural missions and trade unions sympathetic to China in other countries. People’s diplomacy also involves the promotionng of cultural ties through exchanges of students, artists, tourists and so forth, in order to keep open channels of communication between countries, and shape foreign public opinion and, indirectly, official policy.

3 Historian of modern Japan Peter O’Connor has discussed the difficulties inherent in evaluating the influence of informal diplomacy in his ‘Introduction’ to Japan Forum 13:1 (2001), pp. 1-13, p. 8.

4 For an account of the school’s early years and its Puritan ethos, see Noriko Kawamura Ishii, American Women Missionaries at Kobe College, 1873–1909 (Routledge, 2004).

5 Takeda Kiyoko, Deai: sono hito, sono shisō (Kirisutokyō shimbunsha, 2009), p. 29.

6 Takeda, Deai, p. 30. This Chinese student is identified as 龔甫生 (Gong Fusheng) in an NHK ETV special series on the Cold War era (ETV tokushū shirīzu “Ampo to sono jidai”), first broadcast on 1 August 2010.

7 Upon returning to Japan, Takeda had been apprised of the persecution of prominent Christian social reformers and members of Churches that had not joined the official umbrella organisation Nippon Kirisuto Kyōdan (later, the United Church of Christ) in the summer of 1941. She was also aware of the intense pressures faced by Christian educators and Christian schools, where failure to observe rituals of Shintō worship came to be seen as the ‘litmus test of patriotism’ (John Breen, ‘Shinto and Christianity, A History of Conflict and Compromise’, in Mark R. Mullins (ed.), Handbook of Christianity in Japan (Brill, 2003), pp. 250-276, p. 263).

8 Through contact with the Indian YWCA and the wife of the Indian Finance Minister, a Christian, Takeda was invited to meet with Nehru at his New Delhi residence. His particular interest in Japan’s postwar economic recovery led to several repeat invitations.

9 Okazaki Masafumi details the positive response to the proposal to establish a Christian University in ‘Chrysanthemum and Christianity: Education and Religion in Occupied Japan, 1945–1952’, Pacific Historical Review (2010) 79:3, pp. 393-417, pp. 410-415.

10 While employed at ICU, Takeda attended WSCF Conferences in South Asia, WCC meetings and conferences in the United States, Asia, Eastern and Western Europe, and Australasia, and meetings of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia in the United States and Asia.

11 As director of ICU’s Institute for Asian Cultural Studies between 1974 until 1983, Takeda oversaw the Institute’s close engagement with Asian scholars, visits by Asian visiting researchers, and collaborative research projects between Japanese and Asian scholars.

12 John Howes, ‘Internationalism and Protestant Christianity in Japan before World War II’, The Japan Christian Review 62 (1996), pp. 54-66, p. 54.

13 John F. Howes, ‘Nitobe Inazo’, Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan Vol 6 (New York: Kodansha, 1983), pp. 21-22. Howes considers Nitobe to have been ‘one of the most cosmopolitan Japanese of his generation’ (p. 22).

14 Nitobe’s multiple allegiances caused inner conflict: he struggled to reconcile his love of country with the denunciation of Japan’s aggressive state policies by sections of American society formerly friendly towards Japan. His patriotism was neither chauvinistic nor did it denote unconditional loyalty to the emperor. Howes relates Nitobe’s strenuous efforts to explain Japan’s presence in Manchuria to his weakening health and death (‘Nitobe Inazo’, p. 22), and Davidann describes his plea for American understanding on Manchuria (Cultural Diplomacy in U.S.-Japanese Relations, 1919–1941, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pp. 152-154). Neither Nitobe nor Tsurumi engaged in public relations work for the Japanese state; both were motivated by their patriotism and close feelings for Americans, and both were opposed to militarism, if not, colonialism per se.

15 Sasaki Yūsuke, ‘The Institute of Pacific Relations and People-to-People Diplomacy: A Comparative Analysis of the Institute’s Unofficial Diplomacy and Track II Diplomacy’, unpublished paper presented at the 16th Colloquium (25 July, 2009) of the Japanese Association for American Studies.

16 Yanaihara’s Christian identity, love of country, and his involvement in the unofficial diplomacy of the IPR were closely imbricated. His faith and sense of public justice infused his patriotism and underpinned his political judgement to an unusual degree. For Yanaihara, faith (love of God) sanctioned critical judgement of the state; this was ‘the manifestation of true patriotism’ (Takashi Shogimen, ‘“Another Patriotism” in Early Shōwa Japan (1930–1945)’, Journal of the History of Ideas 71:1 (January 2010), pp. 139-160, p. 156).

17 Takeda alludes to this connection when she notes that the term ‘intellectual exchange’ was coined by Nitobe, that the purpose of the Committee was to advance and develop Nitobe’s spirit (seishin), and that those people who were behind it were all, directly or indirectly, Nitobe’s students (see ‘Nichibei chiteki kōryū i’inkai no koro’, Tsuisō Matsumoto Junji (Kokusai Bunka Kaikan, 1990), p. 153).

18 Davidann, Cultural Diplomacy in U.S.-Japanese Relations, 1919–1941, p. 108.

19 Elise Boulding, Building a Global Civic Culture: Education for an Independent World (Syracuse University Press, 1990), p. 132.

20 This literature includes essays by Elizabeth Dorn Lublin and Manako Ogawa on the World Christian Temperance Union (‘Mary Clement Levitt, Japan, and the Transnationalism of the WCTU, 1886–1912’, in Kimberley Jensen and Erika Kuhlman (eds), Women and Transnational Activism in Historical Perspective (Republic of Letters Publishing, 2010), pp. 13-36; ‘“The White Ribbon League of Nations” Meets Japan: The Trans-Pacific Activism of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, 1906–1930’, Diplomatic History 30: 1 (January 2007), pp. 21-50); and essays by Helen S. E. Parker, Karen Garner and Elizabeth A. Littell-Lamb on the YWCA (‘Women, Christianity and Internationalism In Early Twentieth-Century Japan: Tsuda Ume, Caroline McDonald and the Founding of the Young Women’s Christian Association in Japan’, in Hiroko Tomida & Gordon Daniels (eds), Japanese women : emerging from subservience, 1868-1945 (Global Oriental, 2005), pp. 178-191; ‘Global Feminism and Postwar Reconstruction: The World YWCA Visitation to Occupied Japan, 1947’, Journal of World History 15:22 (June 2004), pp. 191-227; and ‘Localizing the Global: The YWCA Movement in China, 1899 to 1939’, in Jensen and Kuhlman (eds), Women and Transnational Activism, pp. 63-87).

21 Personal communication, 23 January 2011.

22 It is instructive to contrast Takeda’s approach to unofficial diplomacy with that of women like the Chinese-American Anna Chennault, whose extensive ‘inside track’ contact with American policy-makers and lobby groups Catherine Forslund has examined in Anna Chennault: Informal Diplomacy and Asian Relations (Scholarly Resources, 2002). Unlike Chennault, whom Forslund describes as an ‘ardent Cold-Warrior’ and skilled in the art of entertaining, Takeda neither forthrightly expressed an ideological posture in regards to Japan’s relations in Asia nor cultivated a reputation as skilled hostess whose generous hospitality or mere presence could facilitate diplomatic engagement or the promotion of business or political relations (p. xvi).

23 This contrasts clearly with the posture of journalists, prominent businessmen and former politicians comprising the so-called “Japan Lobby”. Howard Schonberger describes the Lobby’s campaigns to change American policy towards occupied Japan in ‘The Japan Lobby in American Diplomacy’, Pacific Historical Review 46:3 (August 1977), pp. 327-359.

24 Personal communication, 23 January 2011.

25 Takeda Kiyoko’s writings on Ichikawa include chapters in Fujin kaihō no dōhyō: Nihon shisoshi ni miru sono keifu [Milestones of Women’s Liberation: the lineage in Japanese intellectual history] (Domesu Shuppan, 1985); Sengo demokurashī no genryū [The origins of postwar democracy] (Iwanami shoten, 1995); and articles in Asahi Jānaru (17-24 August, 1984), pp. 36-40 and Japan Quarterly 31:4 (1984), pp. 410-415.

26 Ichikawa saw herself as part of a global community of women that existed alongside, and in complementarity with, women’s membership of the nation-state, and referred to her internationalism as “kokumin gaikō” (people’s diplomacy) (see Barbara Molony, ‘From “Mothers of Humanity” to “Assisting the Emperor”: Gendered Belonging in the Wartime Rhetoric of Japanese Feminist Ichikawa Fusae’, Pacific Historical Review 80:1 (February 2011), pp. 1-27, p. 20).

27 Takeda distinguishes this strong sense of her own Japanese identity from patriotism in ‘Kōkansen no jikan’, in Tsurumi Shunsuke, Katō Norihiro, and Kurokawa Sō, Nichibei Kōkansen (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2006), pp. 460-464, p. 460.

28 This sentiment was influenced by Niebuhr’s political realism of her mentor, and by her mother’s injunction that a landlord’s household must care for its tenant farmers (Takeda Kiyoko, ‘Seikatsu to shisō’, Shisō no kagaku (December 1995), pp. 4-20, p. 10 passim).

29 Takeda, Deai, pp. 101-102.

30 For an overview of the huge scale of United States government investment in the Philippines through its rehabilitation programme, see Vellut, J. L., ‘Japanese Reparations to the Philippines’, Asian Survey 3:10 (October 1963), pp. 496-506, p. 497.

31 Dingham, ‘The Diplomacy of Dependency: The Philippines and Peacemaking with Japan, 1945–52’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 67:2 (September 1986), p. 310.

32 John Price, ‘A Just Peace? The 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty in Historical Perspective’ (JPRI Working Paper No. 78: June 2001) (accessed 28 February 2011).

33 Ron O’Grady, personal communication, 7 April 2009.

34 In 1970, 85 percent of the population of the Philippines was Roman Catholic; three percent affiliated themselves with the Protestant denomination; and fewer than four percent identified as Muslims (Elíseo A. De Guzman, ‘Population Composition’, in Mercedes B. Concepcion (ed.) Population of the Philippines (Population Institute, University of the Philippines, 1977), pp. 35-60, p. 57, citing the Census Report for 1970).

35 Grace Gorospe-Jamon and Mary Grace P. Mirandilla, ‘Religion and Politics: a look at the Philippine experience’, in Rodolfo C. Severino and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (eds), Whither the Philippines in the 21st Century? (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2007), pp. 100-126, p. 112.

36 Takeda Kiyoko, personal communication, 23 January 2011.

37 Takeda Kiyoko, ‘Supirichuaru na kawa no nagare’, Tokyo YWCA (591), 1 October 2005, p. 1.

38 In 1953, Korean students rebuffed Takeda’s expression of apology and offer of material assistance (‘Korean Travel Diary, 1953’ in Frank Engel, Living in a World Community: An East Asian Experience of the World Student Christian Federation, 1931–1961, WSCF Asia-Pacific, 1994, pp. 71-72).

39 See Timothy Brook, ‘Toward Independence: Christianity in China Under the Japanese Occupation, 1937–1945’, in Daniel H. Bays (ed.), Christianity in China From the Eighteenth Century to the Present, Stanford University Press, 1996), pp. 317-337.

40 Daniel H. Bays, ‘Leading Protestant Individuals’, in R. G. Tiedemann (ed.), Handbook of Christianity in China (Brill, 2009), pp. 613-627, p. 617.

41 Bays (2009), p. 619.

42 He was general secretary of the YMCA for 16 years from 1916. Bays (2009), pp. 617-618.

43 Gao Wangzhi, ‘Y. T. Wu; A Christian Leader Under Communism’, in Bays (ed.) Christianity in China, pp. 338-352, p. 343.

44 Bays (2009), p. 877.

45 She had hoped to attend the World Conference of Christian Youth in Oslo, Norway, as a Japanese delegate by the Japan YWCA and YMCA in 1947 but had been denied travel permission by SCAP.

46 Elaine Sommers Rich, ‘Japan’s World Council President, Kiyoko Takeda Cho’, The Christian Quarterly (Spring 1974), pp. 106-108.

47 ‘Watashi no naka no “Ajia”’, p. 272.

48 The seats on the KML flight of Takeda and her travelling companions (three other Japanese delegates to the WSCF conference) were seized by Kuomintang officers fleeing from the advancing People’s Liberation Army, and they had to wait ten days for seats on the next onward flight to Kandy (Takeda, Deai, pp. 94-95).

49 ‘Watashi no naka no Ajia’, p. 272.

50 For Takeda’s account of her association with Ting Kuang-hsun, see Takeda, Deai, pp. 142-144.

51 Xu Guangping was a former student and later de facto wife of the famous writer, Lu Xun (1881-1936). A dialogue between Takeda and Xu about Lu Xun featured in the October 1956 issue of Sekai (see ‘Taidan: Ru Shun no koto nado’, Sekai 130 (October 1956), pp. 179-185).

52 China was not a signatory of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951. Neither the government of the People’s Republic of China nor the government of the Republic of China was invited to the Peace Conference at which the Treaty.

53 Donald C. Hellmann, ‘Japan’s Relations with Communist China’, Asian Survey 4: 10 (October 1964), pp. 1085-1092, p. 1085.

54 Ryozo Kurai describes the evolution of Sino-Japanese relations between 1955 and 1960 in ‘Present Status of Japan-Communist China Relations’, The Japan Annual of International Affairs 1 (1961), pp. 91-157.

55 For details of the deterioration of Sino-Japanese relations under Kishi Nobusuke, see Kurai, ‘Present Status of Japan-Communist China Relations’, pp. 93-99.

56 Hellman, ‘Japan’s Relations with Communist China’, p. 1086.

57 Caroline Rose, Sino-Japanese Relations, Facing the past, looking to the future? (Routledge, 2005), p. 31.

58 See this link (accessed 1 March 2011).

59 Takeda Kiyoko, ‘Taheiyō no heiwa—Nichū kokkō kaifuku no ki ni omou—’, Sekai 324 (November 1972), p. 94.

60 Takeda did not adduce any specific evidence of this, but may have been referring to the tendency of Japanese governments in the 1950s and 1960s to emulate American anti-China rhetoric and policy.

61 Takeda, ‘Taheiyō no heiwa—’, p. 96.

62 For a list of ‘issues in Sino-Japanese relations’ (including official acts, statements, and meetings) between 1982 and 2002, see Caroline Rose, Sino-Japanese Relations, p. 3.

63 In the 1950s, to remind Japan of its past mistakes was a standard tactic of Chinese negotiators; the powerful implication of insincerity would put the Japanese side on the defensive and turn the discussion in their favour (Kazuo Ogura, ‘How the “Inscrutables” Negotiate with the “Inscrutables”’, The China Quarterly 79 (1979), pp. 529-552, p. 533).

64 Akira Iriye, ‘Chinese-Japanese Relations, 1945–90’, The China Quarterly 124 (December 1990), pp. 624-638, p. 635.

65 The resulting publication was a reader that contained detailed information about Japan’s aggressive war in East Asia (Caroline Rose, ‘Sino-Japanese relations after Koizumi and the limits of ‘new era’ diplomacy’, in Christopher Dent, China, Japan and Regional Leadership in East Asia (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008), pp. 52-64, p. 62 (fn. 8)). This successful outcome was perhaps the result of the sustained effort of organised civil society actors without state interference. Other collaborations that receive state support, such as the China-Japan Joint History Committee have been less productive. — President Hu Jintao and Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō agreed upon the research agenda in October 2006, but when the final report was released early in 2010, it was clear that the Committee was unable to resolve several key issues. See ‘Japan, China still at odds over Nanjing’, The Japan Times (1 February 2010).

66 Despite an apparent thaw in Sino-Japanese relations in 2006 and 2007 (Rose, 2008), the staging in September 2010 of anti-Japan protests at the detention of the Chinese skipper of a fishing boat that collided with two Japanese coast guard vessels near the long-contested Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in front of the Japanese Embassy in Beijing on the 79th anniversary of the Mukden incident, suggest that “the history problem” still plagues diplomatic relations between Japan and China.

67 For a discussion of the constructive role of Japanese non-government organisations, including the Asian Network for History Education, in maintaining relations at the sub-state level, see Utpal Vyas, ‘Japan’s international NGOs: a small but growing presence in Japan-China relations’, Japan Forum 22: 3-4 (2010), pp. 467-490.

68 Sōkeirei is the romanised transliteration of the Japanese correlate word for Soong Ching Ling. After the death of her husband Sun Yat-sen, Soong Ching Ling dedicated herself to working for world peace and improving the welfare of Chinese children and youth. The China Soong Ching Fund was established in December 1985 to continue her work and, in addition to the Sōkeirei Japan Fund, independent organisations were established in her honour in the United States, Canada and Hong Kong. For further details on Soong Ching Ling, the China Soong Ching Ling Foundation and its global network, see this link(accessed 1 March 2011).

69 According to Kubota Hiroko, its board members are card-holding members of the Chinese Communist Party. (Interview with Kubota Hiroko, 24 January 2011, at the Hachioji offices of the Joint Japan-China Project Committee for the Sōkeirei Fund (Sōkeirei kikinkai Nitchū purojekuto i’inkai (JCC), Tokyo.)

70 Its core projects were continued by the JCC under the leadership of Kubota Hiroko, a scholar of Sun Yat-sen and Takeda’s associate at SJF. The JCC added maternal health to educational support, and became a certified non-profit organisation in 2002. It operates in a more modest manner than SJF with the support of interested local citizens.

71 Utsunomiya Tokuma, an Liberal Democratic Diet member who supported the strengthening of Sino-Japanese relations, and led official delegations to China before normalisation, served as President of the SJF from its establishment until his death, and donated office facilities.

72 Interview with Kubota Hiroko, 24 January 2011.

73 Interview with Kubota Hiroko. ODA figures are detailed on a chronology of the JCC prepared by Kubota (in the author’s possession).

74 For example, with support of electronics companies Toshiba and Sony, SJF arranged the installation of lighting and communication system in the Children’s Science and Technology Pavilion at the Soong Ching Ling Children’s Science Park in 1986. It also organised for Japanese experts in science education to be sent to China to oversee the development and implementation of practical science instruction.

75 The one exception was the Japanese Communist Party. Kubota states that the fact that the JCP was not involved encouraged other parties to engage with the SJF (Interview with Kubota Hiroko, 24 January 2011).

76 The themes of these sessions, edited versions of the lectures given at the first seven sessions, and Takeda’s own questions about Chinese democracy, are compiled in Takeda Kiyoko, ‘Jo ni kaete’ in Takeda Kiyoko (ed.), Chūgoku no kirihiraku michi, Nihon yori miru (Keisō shobō, 1992).

77 Takeda Kiyoko, ‘Jo ni kaete’, p. i. For an account of Sun Yat-sen’s many Japanese friends and Japanese support for Chinese Republicanism’s and its struggle against Western imperialism, see Marius Jansen, The Japanese and Sun Yat-sen (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967).

78 A plea issued in the course of an address on the emancipation of woman before approximately one thousand women at Kobe Prefectural Girls’ School, in November 1924, when Sun Yat-sen delivered his famous “Greater Asianism” speech in which he urged Japan, as the most modernised East Asian country, to assist China as an older brother would a younger brother.

79 The anonymous author of a profile of Takeda Kiyoko in the May 1950 issue of Chūō kōron described her as the ‘first reporter on postwar India’ (p. 96). For examples of Takeda’s journalistic writing about her early postwar travels, see her account of meeting with other Asian Christian youth in Sri Lanka in which she reflects on Asia’s painful fight for independence, ‘Atarashī Ajia e no michi’ [The path towards the new Asia], Fujin kōron (May 1949); her essay on her interview with Nehru, ‘Indo no chichi: Nēru kaikenki’ [Record of Interview with Nehru, India’s father], Sekai hyōron 4-5 (May 1949); and her encounter with the legacy of Japanese aggression in the Philippines, ‘Firippin ni nokotta sensō no kizuato’ [The scars of war in the Philippines], Fujin gahō 569 (February 1952). On her travels in the new China and meetings with Chinese Christians, see, for example, ‘Chūgoku kirisutokyō ni jiyū’ [The freedom of Christianity in China], Mainichi shinbun (15 June 1956), and ‘Atarashï shakai ni jiritsu suru kyōkai’ [Independent church in a new society], Fukuin to sekai (August 1956), pp. 35, 46-53.

80 Thomas Risse, ‘Transnational Actors and World Politics’, Handbook of International Relations (Sage Publications, 2002), pp. 255-274.

81 Richard Langhorne, ‘The Diplomacy of Non-state Actors’, Diplomacy and Statecraft 16 (2005), pp. 331-339, p. 333.

82 See, for example, Langhorne, ‘The Diplomacy of Non-state Actors’.

83 See, for example, the works referred to in footnote 20 infra., none of which consider the role of such organisations and their individual members in unofficial diplomacy.