The Day the Sun Rose in the West. Bikini, the Lucky Dragon and I

Ōishi Matashichi and Richard Falk

Translated by Richard H. Minear

Ōishi Matashichi, a fisherman aboard The Lucky Dragon #5, in a new book, tells the story of the 1954 Bikini Hydrogen bomb Bravo test that transformed his life and touched off the world anti-nuclear movement. The Asia-Pacific Journal is pleased to offer excerpts from Richard Falk’s foreword and Ōishi’s riveting account of the bomb which exploded with a force 1,000 times that of the Hiroshima Bomb and left its imprint on the lives of the surviving members of the crew and our understanding of nuclear weapons and US atomic diplomacy.

Richard Falk, from the Foreword

If the curse of nuclearism is ever to be removed from human destiny, it will be the result of a popular movement from below, not an illuminating flash of moral and political insight from the commanding heights of power. Dwight Eisenhower said as much when he warned the American people fifty years ago, as their president, about the existence of a military-industrial complex that biased government toward militarist policies. As often noted, however, it was discomforting that Eisenhower waited until his farewell speech, a time when he no longer had any power of decision or political leverage, to issue the warning. As of 2010, this militarist reality is far more entrenched in the governmental structures of the United States and its global network of military bases than it was in the 1950s, and it is now strongly reinforced by a compliant media and a seemingly pacified and apathetic citizenry. I hope that citizenry will soon be mobilized to oppose the revived American militarism evident in a bloated defense budget and a renewed surge of military interventionism, most prominently in Afghanistan.

It is from such a vantage point that I welcome with the deepest gratitude Ōishi Matashichi’s exceptional book. It relates a poignant story with passionate authenticity, and it is a story that has broad significance. It explains why it would be essentially an exercise in futility to expect governments, left to their own devices, ever to come to their senses and get rid of or even control this infernal weaponry. Ōishi was a survivor of the Bravo test of a hydrogen bomb on March 1, 1954, that has made the name Bikini synonymous with lethal radioactivity. That nuclear test was the largest ever. It involved a 15-megaton bomb whose fallout poisoned a vast stretch of the Pacific Ocean, an explosion measured at about 1,000 times the magnitude of the Hiroshima bomb that itself had achieved apocalyptic results when dropped on a heavily populated city. Ōishi was one of twenty-three crew members on the Lucky Dragon #5, which was at least ten miles outside the supposed danger zone at the time of Bravo. Revealingly, Bravo had double its expected explosive force. Partly due to the predicted unfavorable winds, it dumped a thick layer of ghostly white radioactive “death ash” on the Lucky Dragon #5, contaminating all those on board. This book tells the harrowing tale of disease for all and premature death for more than half of those exposed on the vessel. But it goes much further, also depicting the struggle of this one man to let the people of Japan know that a dark nuclear shadow was cast across their lives. To tell this story required the greatest fortitude and a willingness to endure an endless series of hostile encounters with the powers that be.

|

Ōishi Matashichi, excerpt from The Day the Sun Rose in the West

Fifty-five years have passed, yet I continue to testify about the Bikini Incident because the dangers the Incident entailed are horrific. If for whatever reason a nuclear war breaks out, what will become of this planet and of the human race? The answer is crystal clear.

|

Ōishi Matashichi |

By a twist of fate, we simple fishermen encountered the hydrogen bomb test. Suffering from prejudice and discrimination for being a nuclear victim, I fled my hometown and tried to hide in the crowded city of Tokyo. But I couldn’t outrun the devil—the radiation that had penetrated deep into my body. It haunted all of us, robbed me of my first child, and took the lives of my fellow fishermen, one after another.

I have often discussed the Bikini Incident with schoolchildren and students in Japan. In winding up my talks, I always make sure to end as follows:

No matter what the issue, we must never start another war. Fortunately, Japan has a Peace Constitution, and it protects us. Japan’s Self-Defense Forces should never engage in killing human beings. In accordance with our Peace Constitution, they should become Disaster Relief Teams, both in name and in reality. This is the way, I think, that Japan will become a peaceful country trusted and loved by every other country in the world. It will also help get rid of nuclear weapons and war. I hope you, the rising generation, will choose to take this road. I hope you develop a broad vision, learn to look at things from many different angles, not only from the front, but also from the sides, the back, and above.

I have not yet had the opportunity to talk with schoolchildren and others in the United States. But if I had that opportunity, my message would be much the same: It is vital that you develop a breadth of vision to see issues from all angles and work to rid the world of nuclear weapons and war.

The Ill-Fated Voyage

The Lucky Dragon #5 was a wooden ship listed at 99.09 tons. Her actual weight was 140 tons. At the time, wooden ships were limited to 100 tons. So the ship weighed 99.09 tons to meet the limit, then inspectors were bribed and 40 tons added. Come to think of it, she was a scary ship. She was eighty-three feet long, nineteen feet at her beam, and drew eight feet.

|

The Lucky Dragon #5 in 1954 |

She was built in Wakayama in 1947. A fishery company named Kotoshiro in Kanagawa ordered the ship, and when she was launched, she was christened Kotoshiro #7. She carried a 250-horsepower diesel engine made in 1943. For the next five years, the Kotoshiro-maru #7 fished for bonito, and its catch made it a national leader. In June 1953, Nishikawa Kakuichi of Yaizu bought the seven-year-old ship for twelve million yen (at the existing exchange rate, roughly $34,000). He renamed her the Lucky Dragon #5.

For the five years before I signed on with Lucky Dragon #5, I, too, had been fishing for bonito, on the Shinsei-maru (steel, 150 tons, 250 horsepower). During that time I’d encountered the Kotoshiro-maru #7 at sea a few times. I remember it well because both ships were at full throttle in the chase for bonito, and we’d yelled at each other when we came close to colliding.

To fish for bonito, you work the engine hard. When you find schools of bonito, you chase them at top speed. The schools may not be close to the ship. Seasoned fishermen can spot them with the naked eye even on the horizon. To find a school on the horizon, you look for a flock of seabirds. Sardines surface to elude the bonito. Seabirds hunt the sardines. Spot a flock of birds, and you’ll find bonito.

Nature determines where the fish congregate. Big or small, fish congregate where the warm Japan Current meets the cold Okhotsk Current. This is prime fishing territory for all parties—sardines, bonito, seabirds, fishermen. If you’re later than other ships in reaching the fishing ground, you’re in big trouble. A seesaw game develops: you scramble after the school with one eye on the movements of the other ships.

Forty or fifty men line up eagerly along the rail, fishing rods in hand. They shout, “Don’t let them beat us out!” The sea turns into a battlefield. The ship’s pistons roar, as if about to explode, and the ship races ahead at full steam. The ship that figures out where the school is headed and arrives first at its leading edge wins. It makes a world of difference in the catch. I loved the excitement of fishing for bonito.

I remember seeing the Kotoshiro-maru #7 running nimbly and well. But I didn’t know the Kotoshiro-maru #7 had become the Lucky Dragon #5. I learned this only when I was hospitalized after the Bikini test. The Kotoshiro-maru #7 had fulfilled her bonito-fishing mission and was worn out. So after being remodeled for tuna fishing in the calmer southern seas, the ship was sold to a company in Yaizu.

Just at that time, the bonito catch was down, and on the open ocean, bonito fishing was giving way to tuna fishing. By then I’d become a full-fledged fisherman and hoped to sign on with a larger ship, fish for tuna in the Indian Ocean, save some money, and rebuild my dilapidated house. Its walls were cracked, and moonlight shone through the cracks.

The five years of my life leading up to this point had been tough ones. I had to hire on to a ship in 1945. In September of that year, with Japan in the midst of post-defeat chaos, my father died suddenly in a shipping accident. At forty-two, he was still in his prime. My family was in a major bind.

During the war my father and my older sisters worked at the local Toshiba factory. But with Japan’s defeat, its business had come to a stop. The factory provided jobs for its workers by such means as buying small fishing ships and making salt pans on the shore. My sisters were working at the salt pans, and my father managed the ships. He had learned a bit about coastal fishing from his father. The accident happened while he was working on a ship up on blocks. Carpenters mistakenly moved the jacks holding it up, the ship rolled over on him, and Dad was crushed to death. Troubles come in bunches. Despondent, my grandfather died three months later, as if following his son in death. It was December 30, two days before New Year’s.

Our household, then, consisted of Mom, my two elder sisters, my three younger brothers, and myself. Amid the chaos that followed Japan’s defeat, we were now only women and children, and we soon found ourselves in the depths of poverty. We didn’t have food for each day, and everything fell on my shoulders—I, the oldest of the four brothers. School was wholly out of the question. If I didn’t support the whole family, if I didn’t start working immediately, we’d starve.

I quit school when I was in eighth grade, and at fourteen, out of harsh necessity, I became a fisherman. I was plunged into a world full of veterans back from the war and all kinds of rough fellows. It was a tough apprenticeship: I was beaten, schooled, and somehow—piling perseverance on perseverance—became an honest-to-goodness fisherman. I applied for work on a large tuna-fishing ship based in Shizuoka and prepared to go aboard, dreaming of one day becoming skipper or ship’s master.

The ship I wanted to work on hadn’t come back yet from the Indian Ocean, so until it did, I worked on ships going to Suruga Bay to catch shrimp. You catch them at night, so it’s hard work, but there’s money in it. It was then that a colleague from the days I worked on the Shinsei-maru asked me to work with him on the Lucky Dragon #5. I accepted his offer, thinking it would only be until the big ship returned, but I ended up making five voyages on her.

During the first three voyages, I learned the basics of tuna fishing from the likes of Onodera, the ship’s master and a tuna fishing pro; Tomita, the bo’sun; and Sasaki, the engineer.[i] When Onodera left the ship after the third voyage, Misaki Yoshio from Yaizu took over as ship’s master; Lucky Dragon #5 was now a Yaizu ship both in name and reality.

On December 3, 1953, when Lucky Dragon #5 was returning to port from my fourth voyage, we were seized off Indonesia by an Indonesian patrol ship because it suspected we’d intruded into Indonesian waters. We’d been careful to stay outside the thirty nautical miles Indonesia claimed, but we were escorted to Halmahera; I was in charge of the catch, so I worried the tuna would go bad, but we were released the next day.

Then came the ill-fated fifth voyage. Captain Shimizu had left the ship for a hemorrhoids operation, and in his place Tsutsui Hisakichi (twenty-two years old), who had his license, became captain. My secondary responsibility was refrigeration. On this voyage, things went wrong from the first. One thing after another happened. Right before leaving Yaizu, five tuna-fishing professionals jumped ship, including Tomita, the bo’sun, and Sasaki, the engineer. They couldn’t get along with Misaki, the young new skipper, nor could they get used to the paternalistic style particular to Yaizu, with crewmembers treated as family. Fate is a strange thing. That was the moment roads diverged: those who jumped ship were saved, and those of us who stayed became linked to death.

To replace those who left, five new people signed on: Masuda, Suzuki, Yoshida, Saitō, and Hattori. Masuda signed on for only the one voyage, and Suzuki, too, thought he’d stay for only the one. For one reason or another, four crewmembers were late in reporting.

On January 22, 1954, at 11:30 a.m., Lucky Dragon #5 sailed from Yaizu, with a hearty send-off from relatives and friends. The crew numbered twenty-three, between eighteen and thirty-nine years of age; seven were married, and sixteen were single. We were young: our average age was twenty-five. The next day, January 23, I turned twenty.

It didn’t take long for the misfortunes to begin. When we neared the center of Suruga Bay, we noticed we’d forgotten to load a spare crank, a major engine part, and diverted to a nearby port, Ogawa. We loaded the part and tried to set sail, but this time we ran aground on a sandbar. We asked a mackerel fishing ship to tow the Lucky Dragon #5 off, but the rope parted, and nothing worked. We had no choice but to wait for high tide; finally, at 5:30 in the evening, we left the harbor.

Then, on the second day, we got caught in a winter low-pressure system. The seas were rough, and our old ship tossed like a leaf tossed about on the huge waves. I can’t forget how frightening it was. For three days and three nights, huge seventy-foot waves surged toward us, and the ship disappeared up to its masts in the troughs. At night, lit up by the searchlight, we could see the giant waves pressing in on us. Far from toughening us, it made us think we were standing at the gates of hell.

In such times, you reduce speed, keep your bow into the wind, and let the great waves roll past. But that isn’t always enough. If the bow catches a wave, the entire blue-black wave courses through the ship from stem to stern. When that happens, the water collects in the hull and soon melts the ice you’re carrying to refrigerate the catch. You have to pump the water out. The watch, who also helps with steering, hooks up a hand pump on the hatch to bail her out. He pumps away while watching for approaching waves and holding tight to the pump so that he won’t be washed overboard.

One time our ship was hit by a giant wave and came close to capsizing. Had the engine died then, it would have been the end of us. The ship would certainly have capsized. But the engine didn’t die, the ship righted itself before the next wave, and we survived.

It was when we had managed somehow to get past the low-pressure system and were passing Torishima that the ship’s master informed us suddenly that our destination had been changed: “We’re headed for Midway.” Midway is located some 2,000 miles east of Japan. It’s known for its rough seas. No one—not the captain, not the engineer, not the radio operator—had been told about this. On our previous voyage, we’d come back with a full load of yellowfin tuna, but they’d brought lower prices than the bigeye tuna our sister ship had brought back from the seas off Midway. We’d thought we were heading for the Banda Sea or the Solomon Islands, calm waters. But instead we headed east, for rougher waters.

The Lucky Dragon #5 had been built in the aftermath of the war, with second-hand lumber picked up here and there. Her hull and engine had gotten old, and water was pooling in its hull and seeping into the refrigerated tanks. In addition, we weren’t equipped for cold weather. Naturally, the crew grumbled and voiced their anxiety. But on board, the ship’s master’s word is law. In the end, the ship turned toward Midway, and on February 7 we arrived at the fishing grounds.

. . . .

Two hundred miles southwest of Midway. 2:45 a.m., February 7. Water temperature: 71 degrees Fahrenheit. Air temperature: 69.5 degrees Fahrenheit. Clang! Clang! At the signal of the bell on the bridge, the skipper shouted, “Lay out the lines!” It was the start of our first cast. Our bait is frozen saury and whole sardines pickled in rice-bran paste. At most, we lay out 330 lines, a job that takes four hours.

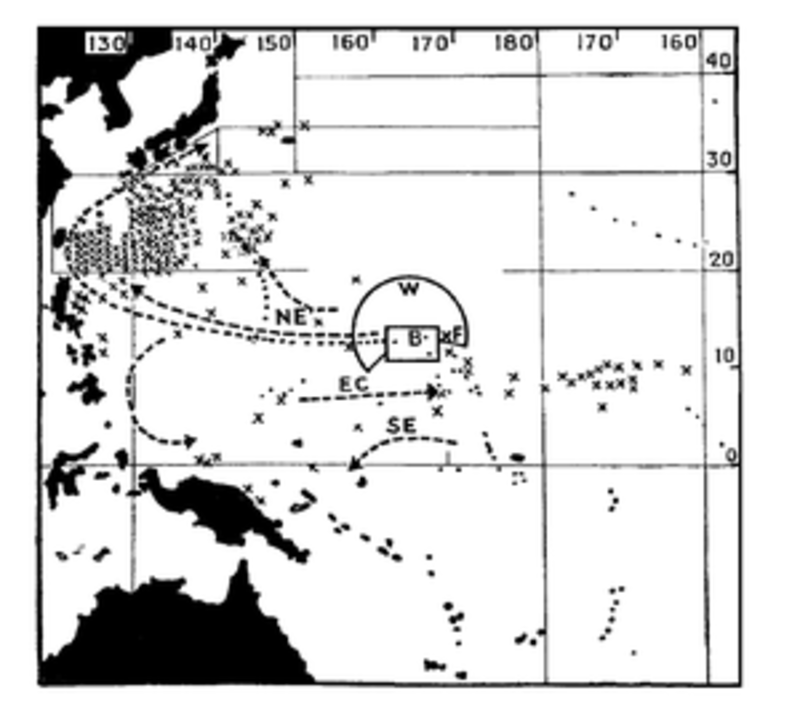

|

Position of Lucky Dragon #5 at the time of the Bikini test |

The ship slows down for this work, but if each man at his post doesn’t pay out line at the same speed as the ship, there’s big trouble. You can’t ever relax your guard. If you happen to hook your finger on the fishhook of a long line that’s being drawn with great force into the water, your whole body will go with it, and you’re a goner. The lines are pulled up two hours later, and between them the two tasks, setting the lines and pulling them, take thirteen hours; it’s tough work. If the fish are biting, we repeat the process.

A single line is about 1,000 feet long. It has five hooks fixed to it, like branches of a tree. Each of the points where the lines join is marked with floating green glass balls, each a foot in diameter and covered in netting; these balls are tied to bamboo poles ten feet long, and they support the trunk line. Lighted buoys are fixed to every twentieth line as a guide in case we’re working at night or the lines should break.

Making the lines shorter or longer, depending on the depth of the water, we search for tuna. Water temperature varies with depth, and the currents flow in different directions, too. When there are crosscurrents, the lines go slack, and trouble arises. The season and the fishing grounds are particularly important. Fishing calls for long experience and intuition.

Fully deployed, the 330 lines can reach more than fifty-five miles, and below them, fifty yards beneath the surface, dangle 1,600 fishing hooks baited with saury and sardines to lure the tuna. That day our catch was a single one of the bigeye tuna we were looking for. The rest was junk—fourteen small tuna and some sharks.

The next day, February 8, we cruised, looking for better fishing. The sea was getting rough. The engine was not in good shape, and we came about a few times to examine it.

February 9, our second day of fishing: we encountered strange currents. Here arose another great misfortune. Perhaps because the lines had caught on coral reefs, 170 of them broke and were gone. More than half the lines. For the next four days, until February 12, we searched frantically for them, but we found only twenty-two.

At this point we were still only on our second day of fishing, and we couldn’t simply go home. We added old spare lines to those we’d found, bringing the total to 200 lines, and ran them out twice a day. The ship’s master discussed with the radioman, the captain, the engineer, the bo’sun, and others where to try next. Go north; if we go north, we’ll find tuna that will fetch a good price. It’s also nearer Japan. No, said the others: the northern seas are rough. Both ship and engine are old, dangerous. Indeed, the engine has conked out eight times. South is better; we’ll catch yellowfin tuna, even though they don’t fetch the same price. And the seas were calm. We headed south. Fishing as we went, we sailed gradually south in the direction of the Marshall Islands and approached the waters off Bikini.

Years later I learned that the radioman, Kuboyama Aikichi, had told the ship’s master and the captain, “Since the war, atomic tests have been conducted there and are still being conducted; I have a hunch we’d better not get close to the restricted area.” The captain and the skipper examined the charts but judged we’d be okay because the area off-limits was ninety miles due west from where we’d be fishing.

On August 18, 1952, the Japanese Maritime Safety Agency was notified by the U.S. State Department that a certain area around Eniwetok was off-limits. On October 10, 1953, the U.S. Hydrographic Office announced that the area had been expanded eastward. On November 1 the Japanese Maritime Safety Agency revised its advisory accordingly. The new off-limits zone was rectangular, from 10°15

Our fuel and food were running low. Lucky Dragon #5’s voyages lasted between a month and a half and two months. Her cruising range was about 2,800 miles. After consulting with the engineer, the ship’s master decided that we’d cast our lines a final time on March 1. Radioman Kuboyama wired the decision to Yaizu.

1:05 a.m., March 1. Latitude 12°03 north, longitude 166°56 east. Water temperature: 79 degrees Fahrenheit. 189 lines out. Our fourteenth and final setting of the lines began; we were heading WSW. It took about three-and-a-half hours. Since the wind was blowing ENE, we ran the ship ENE for ten minutes before killing the engine and drifting. At that point we were eighty-seven nautical miles from the center of Bikini Atoll. Seventy-five miles from Bikini. Our position as calculated by the ship’s master was: “Latitude 11°53 North. Longitude 166°35 East,” and it was so recorded in his fishing log. But the captain’s sailing log says we were at “166°18. They say the captain had misunderstood the ship’s master. (The off-limits zone declared by the U.S. military was at 166°16 at east longitude; we were very close to it.) At intervals, we went to the cabin to lie down, even if only for a few minutes. The ship was drifting quietly on the dark sea. Soon it would be dawn.

The Flash, The Roar, and The White Ash

6:45 a.m., March 1. A yellow flash poured through the porthole. Wondering what had happened, I jumped up from the bunk near the door, ran out on deck, and was astonished. Bridge, sky, and sea burst into view, painted in flaming sunset colors. I looked around in a daze; I was totally at a loss.

“Over there!” A spot on the horizon of the ship’s port side was giving off a brighter light, forming in the shape of an umbrella. “What is it?” “Huh?” Other crewmen had followed me onto the deck, and when they saw the strange light, they too were struck dumb and stood rooted to the spot. It lasted three or four minutes, perhaps longer. The light turned a bit pale yellow, reddish-yellow, orange, red and purple, slowly faded, and the calm sea went dark again.

“What the hell?” Our glances were uneasy, our minds puzzled. Something was happening over the horizon. In the engine room, a startled Suzuki Shinzō, who had seen the flash, told Takagi Kaneshige, who had just gotten up, “The sun rose in the west.” Takagi replied that Suzuki was “blowing smoke. What are you saying?” Engineer Yamamoto Tadashi also saw the bright light. He thought the explosion might cause a tsunami and rushed to the engine room.

A shout came from the bridge: “Pull in the lines!” Hearing the ship’s master’s yell, we came to our senses and started to act.

The engine kicked in. Amid its piercing noise, we started pulling in the lines. We went aft to do the work; we ate breakfast by turns. That’s when we heard the roar. The rumbling sound engulfed the sea, came up from the ocean floor like an earthquake. Caught by surprise, those of us on deck threw ourselves down. It was just as if a bomb had been dropped. I flung the bowl I was holding into the air, poked my head into the galley, and watched to see how things would turn out. My knees were quaking. Right after the roar, I heard two dry sounds, “pop, pop,” like distant gunfire. The calmness of the sea contrasted sharply with the light and the sound.

In retrospect, I can see it was then that the lives of the crew, too, went haywire. No one was aware of the sad fate toward which, willy-nilly, we were being drawn. We just kept pulling in the lines. In the dark, people speculated in subdued voices: “An explosion on the ocean floor?” “No—maybe an asteroid.” “An American military exercise?” It simply didn’t occur to me that it could be a nuclear test. I didn’t know an off-limits area existed. I knew nothing about atomic bombs.

Three months later, from his bed at Tokyo University Hospital, Engineer Yamamoto set down his thoughts about the moment and sent them to the Yaizu Lucky Dragon #5 task force: “It called to mind the atomic bomb, and thus death. Moment by moment, it was as if I were being chased by some devil. I hated the ship’s master’s command, ‘Pull in the lines!’ so much I wanted to yell at him.”

Soon the skies began to turn light, and on the western horizon, where the flash had come from, a cloud as big as three or four gigantic towering thunderclouds was rising high into the sky. It had already reached the stratosphere and was no longer in the shape of a mushroom. Even as we watched, and we were upwind from the cloud, the top of the cloud spread over us. I was puzzled: “How can that be? We’re upwind . . .”

Two hours passed—no, a bit more. The sky that had been clear was now covered completely by the mushroom cloud; it was as if a low-pressure system was coming through. Wind accompanied rain, and the waves began to grow. I noticed that the rain contained white particles. “What’s this?” Even as I wondered, the rain stopped, and only the white particles were falling on us. It was just like sleet. As it accumulated on deck, our feet left footprints.

This silent white stuff that stole up on us as we worked was the devil incarnate, born of science. The white particles penetrated mercilessly—eyes, nose, ears, mouth; it turned the heads of those wearing headbands white. We had no sense that it was dangerous. It wasn’t hot; it had no odor. I took a lick; it was gritty but had no taste. We had turned into the wind to pull in the lines, so a lot got down our necks into our underwear and into our eyes, and it prickled and stung; rubbing our inflamed eyes, we kept at our tough task. I was the refrigerator man, and wearing rubber coat and pants and hard hat, I put the catch in the tank. Lots of ash went into the tank, too, blowing in like snow.

Suddenly, Radioman Kuboyama shouted: “If you spot a ship or plane, tell me right away!” He was a small man, but he had a loud voice. He had sensed danger in the series of events. The restricted U.S. zone was close by. It might have been a “pika-don,”[ii] an atomic bomb. If it was known that we’d seen it, there’d be trouble. We had seen it. If we radioed Yaizu, the U.S. military would intercept the message. But if we didn’t radio and they caught us, they’d seize us. If we weren’t careful, they might even sink us. So if we saw a ship or plane we should contact Yaizu immediately to let them know our whereabouts. That’s what was behind Kuboyama’s call.

The atmosphere was tense. Some of the crewmen said that we’d be better off to abandon the lines and run for it. We had reason to be afraid. In 1952, a ship operating in this area had disappeared, mysteriously. There was talk among fishing crews that it might have been shot at and sunk by the U.S. military. Near the Bonin Islands, a U.S. warship had boarded a fishing ship on the grounds that it was intruding into territorial waters, taken it to Wake Island, detained it for a whole month, and even levied a fine.[iii] Off Izu, a ship had been dive-bombed by a U.S. plane, abandoned its lines, and run for home. Many such events had happened. There must surely be U.S. warships or planes nearby, and submarines, too. It wasn’t a comfortable thought. (After patrolling this vast area—nearly four hundred miles east to west and two hundred miles north to south—before the bomb test, U.S. planes had reported no ships in the restricted zone.)

Brushing off the white ash that continued to fall, we kept at the job for six hours. Those six hours were really scary. I remember even now. Once we had pulled in all our lines, we stowed them in a hurry, washed the ash off the deck and off our bodies, and looking neither left nor right, headed home. That last catch was only nine tuna, large and small. Otherwise, only sharks. In setting the lines fourteen times, we’d caught nine tons, one hundred and fifty-nine fish. That wouldn’t even cover the cost of the trip. We kept the sharks; normally, we kept only the fins and threw away the rest. The ship set its course northward and, spreading sail, too, raced at eight knots for Yaizu.

The next day, March 2, Lewis Strauss, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, announced, “On March 1, at its proving grounds in the Marshall Islands, the U.S. 7th Fleet exploded a nuclear device.” I’ve never heard it said that our radioman Kuboyama received that announcement.

Richard Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law, Princeton University, and United Nations Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur for the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

Ōishi Matashichi was born in 1934 and went to sea as a boy of fourteen. On March 1, 1954, the ship on which he was sailing encountered what one crewman called “the day the sun rose in the west.” The Bikini test (Bravo) of the U.S. hydrogen bomb contaminated the ship and its crew with radioactive fallout. Once he had recovered from the dire immediate effects on his health, Ōishi left the sea and became the proprietor of a laundry. Later in life he became a peace advocate—telling his story to groups of children throughout Japan.

Order the book: Ōishi Matashichi, The Day the Sun Rose in the West. Bikini, the Lucky Dragon and I here. ©2011 University of Hawai’i Press. All rights reserved.

Recommended citation: Ōishi Matashichi and Richard Falk, Ōishi Matashichi and Richard Falk, The Day the Sun Rose in the West. Bikini, the Lucky Dragon and I, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 29 No 3, July 18, 2011.

Articles on related subjects include:

• Robert Jacobs, Social Fallout: Marginalization After the Fukushima Nuclear Meltdown

• Say-Peace Project and Satoko Norimatsu, Protecting Children Against Radiation: Japanese Citizens Take Radiation Protection into Their Own Hands

• Yuki Tanaka and Peter Kuznick, Japan, the Atomic Bomb, and the “Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Power”

• Daniel Ellsberg, Building a Better Bomb: Reflections on the Atomic Bomb, the Hydrogen Bomb, and the Neutron Bomb

• Nakazawa Keiji, Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

• Mark Selden, Living With the Bomb: The Atomic Bomb in Japanese Consciousness

• Senator Tomaki Juda and Charles J. Hanley, Bikini and the Hydrogen Bomb: A Fifty Year Perspective