In 2008, Charter 08 declared that “freedom, equality, and human rights are universal values of humankind, and democracy and constitutional government are the fundamental framework for protecting these values.”1 Charter 08’s drafters, of whom the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo is the most prominent, describe themselves as inheriting China’s historical legacy of political reform. They called for a citizens’ movement “so that we can bring to reality the goals and ideals our people have incessantly been seeking for more than a hundred years.” They credit the 1898 Hundred Days of Reform led by the Guangxu Emperor to transform China into a constitutional monarchy with being China’s “first attempt at modern political change,” and the first sentence of their petition reads, “A hundred years have passed since the writing of China‘s first constitution.”

Indeed, this decade, 1898 to 1908, foreshadowed what has been more than a century-long sporadic, often marginal, and as yet unfulfilled movement to eliminate China’s autocratic system and give Chinese people the right to take part in national affairs. As Charter 08 acerbically notes, with “the revolution of 1911, which inaugurated Asia’s first republic, the authoritarian imperial system that had lasted for centuries was finally supposed to have been laid to rest.” All too soon, “the new republic became a fleeting dream.” And, finally, “the ’new China’ that emerged in 1949 proclaimed that ‘the people are sovereign’ but in fact set up a system in which ‘the Party is all-powerful’. . . . Unfortunately, we stand today as the only country among the major nations that remains mired in authoritarian politics.”

The 1898 Hundred Days edicts spanned education, technology, the economy, government administration, ethnic relations, and, most critically, would have begun the transformation of the autocratic monarchy to a system governed by a constitution, with various elements of democratic participation and a balance of power. But, as Charter 08, describes, “the ill-fated summer of reforms . . . were cruelly crushed by ultraconservatives at China‘s imperial court.” After only 103 days, Empress Dowager Cixi staged a coup, the young Emperor was put under house arrest, and the reformers who advised him were executed, fled into exile, or banned from organizing associations.

But the urge for reform was not staunched by the coup at the Qing court. Although the brutal suppression of the coup radicalized some members of the intelligentsia, particularly Chinese students in Japan, who became revolutionaries, a much larger number of reformers began to organize inside and outside of China to gather support for a constitutional system. By 1908, this decade-long movement had grown through a worldwide network of voluntary associations, reform newspapers, and strong leaders, largely located outside of China distant from Qing government control. Most critical, their political message of constitutional reform reverberated with certain local gentry, urban elite and Qing officials inside China. It was this group that kicked off the constitutional petition movement in 1907 and prompted the Qing court to issue its draft constitution a year later.

Impelled by these external and internal currents supporting constitutional reform, and seeking to forestall further calamity to the nation after China was humiliated by the eight-nation alliance that put down the disastrous Boxer uprising, occupied Beijing, and then forced China to pay huge indemnities as reparation, the Empress Dowager herself began to implement elements of the Emperor’s failed 1898 reform program. In 1901, she announced that the court would begin to study the good points of foreign statecraft and adopt those that could help China become rich and powerful. The victory of Japan, a constitutional monarchy, over autocratic imperial Russia, in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 fought on Chinese territory, again jolted the Qing court. Meiji Japan stood as an even more potent model for China, as the only Asian country with the strength to hold its own with Western powers (and one of the eight-country alliance that invaded Beijing in 1900 to fight the Boxers). Following the political example of Meiji Japan, the Qing began to prepare in earnest for China’s gradual transition to a constitutional monarchy, with constitutional study missions abroad, a census, financial analysis and budgeting, writing a legal code, and reorganization of the government before “granting” a constitution and forming a parliament.

However, although the court’s “top-down” reforms were initially welcomed by reform activists outside the government, by 1908 these activists had coalesced into a national petition movement to push the Qing to hasten the transition to constitutional government. Most controversially, many petitioners wanted a parliament to be convened quickly to debate and adopt a constitution rather than wait for the government to carry out lengthy preparations and “grant” a constitution.

As Charter 08 reminds us, the Qing government promulgated the first Chinese constitution in 1908. Announced on August 27 in the midst of the petition movement, it was merely an outline of principles for a constitution that was intended to go into effect nine years later (1916) after extensive preparation at the national, provincial and local levels. This was to be an imperially-granted constitution, which retained the Emperor not as a figurehead but an absolute ruler, with no restrictions on his authority other than the fact his powers were enumerated in the constitution. The parliament was meant only to advise and support the Emperor, not share power with him. Not only would the parliament have no role in writing the constitution or the laws, its subsequent acts were subject to the consent of the Emperor. “The Da Qing Emperor will rule supreme over the Da Qing Empire for one thousand generations in succession and be honored forever,” the Principles began.2

Although the Qing government had opened itself up to political reform in a way hard to imagine in today’s China, and the 1908 constitutional draft delineated rights for law-abiding subjects including suffrage and freedom of speech, press, and assembly, many reform-minded subjects were increasingly disaffected with the court’s conception of a constitutional monarchy. Even the court’s announcement of impending provincial assemblies and a national Political Consultative Council [zizhengyuan] to be formed prior to a true parliament could not dampen the clamor for political participation by China’s urban gentry and merchants, and the constitutional petition movement continued to grow.

One audacious petition that claimed to represent several hundred thousand overseas Chinese provoked the court’s wrath because of the breadth of its demands, the organization and the “most wanted” political leaders behind it, and the large number of signatories. In spirit and content, this petition evokes Charter 08, just as the Chinese government’s vehement reaction to the Charter and to Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Peace Prize echoes the Qing government’s words and actions in response to this petition, which was published in 1908.

|

The 1908 petition was written by Kang Youwei [pictured right], the Emperor’s most influential Hundred Days advisor, who by 1908 was the only 1898 veteran along with his disciple Liang Qichao who still had prices on their heads. In 1899, Kang and Liang, both in exile, had organized what was arguably the first Chinese mass political organization. The Baohuanghui or Protect the Emperor Society [its official English name was the Chinese Empire Reform Association] was launched in Canada and spanned many national borders, with nearly 200 chapters (and a membership of possibly 70,0003) in Chinese communities in Japan, North and South America, Australia, and other places in Asia and Africa, and a broad reach into China. As its name implies, it aimed to restore the Emperor to his throne so that he could bring about a constitutional monarchy. By 1908, Kang had changed the organization’s name to Xianzhenghui4 or Constitutional Association, reflecting the new political opportunities for reformers with the Qing court’s change of course. Kang summoned chapter leaders from around the world to a general assembly in 1907 in New York City, where he announced the new name of the organization and declared his intention to launch Xianzhenghui in China as the first open political party. “Protecting the emperor” no longer seemed necessary, as it appeared that constitutional reform was underway with or without Guangxu’s direct involvement, and it appeared (though this would prove untrue) that his life was not in danger. Kang believed that the people should share power with the monarch, with the people holding the preponderance of power.5 While adamantly opposed to revolution, the Xianzhenghui had a far more expansive view of constitutional reform than did the Qing and championed democracy, popular sovereignty, and government supervision. In his guidelines for the 1907 meeting, Kang explicitly stated:

This society [desires] to expand democracy [minzhu] as its goal. The people6 are the basis of the country, and those in a constitutional government are governed through democratic rights and public discussion. Our country’s democratic rights have not expanded, and we undertake to try hard to expand them to form a national assembly and participate in governing the country.

This society takes the supervision of government as a priority. Our country is not strong, which is caused by government misrule. Citizens must undertake to rise up and supervise it. Citizens must hold the power of the country’s government, because the hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens are the country. Sitting by and watching this corruption is not solely the fault of those who hold power, but of our citizens who are responsible. Not supervising the government is tantamount to abandoning one’s country.7

While Charter 08’s 12,000 signatories were primarily gathered online from Chinese in China,8 Kang’s petition was written on behalf of the overseas Chinese members of the Xianzhenghui.9 It began, “We are from 200 different cities, representing several hundred thousand people. After meeting for open discussion and debate, we came to this agreement and this petition is the result.” It is possible that this discussion took place during the spring 1907 meeting in New York, but it was not until the summer of 1908 that Kang’s petition was published in Xianzhenghui-sponsored newspapers and became known to the Qing court.

As we will see, Kang’s petition roused the Qing government to punitive action before the petition could be formally presented to the court—just as the Chinese government arrested Liu Xiaobo before Charter 08 could be published.

Animating both Charter 08 and Kang’s 1908 petition was the underlying argument that Chinese people must be given the right to participate in national politics and that popular sovereignty was necessary for China to become a truly modern, internationally respected state. Charter 08 drafters called for the “democratization of Chinese politics,” which they claimed would strengthen China as a nation by “fostering the consciousness of modern citizens who see rights as fundamental and participation as a duty.”

Kang’s 1908 petition decried the ignorance and inexperience of the Qing court, which wanted to delay political participation by the people in a national assembly until they were properly educated and to rely instead on court officials to guide the nation. He asserted that the people, not officials, must be in charge of drafting a constitution and that a parliament was the appropriate institution to draft a constitution:

Setting up a constitutional government is just empty words without a parliament to defend it. . . . We, overseas merchants, therefore are of the view that constitutional government must be established before we can save our country and that parliament must be convened before we can have constitutional government. . . .

Constitutional government has already been unequivocally promised in an imperial decree. That it is slow in coming is due to the fact that some are not sure that the people are sufficiently enlightened and fully qualified [for parliamentary government]. China is a vast country with an immense population of 400 million people; her schools have developed and new knowledge has been pursued in earnest. There must now be countless persons well versed in affairs of the world. To say that we cannot find a few hundred individuals qualified to be members of parliament is unduly to belittle China and her people.

Most of the officials now serving in the government have never traveled abroad or even in all the provinces. They have no understanding of matters relating to agriculture, industry, commerce, mining, or to the customs and usages of the people. All the matters discussed above should be the responsibility of the legislators.

Both Charter 08 and Kang’s petition were coherent political manifestos, laying out transformative visions for China that stood in stark contrast to the existing systems. Charter 08 seeks an end to one-party rule, a new constitution that is “beyond violation by any individual, group, or political party,” election of a representative government at all levels, freedom of expression, press, religion and association, abolition of the rural-urban registry system [hukou], division of power among different branches of government, a legal system that both protects the rights of citizens and limits the reach of the government, and a federated republic embracing the mainland, Hong Kong, Macao, and ultimately Taiwan—in short, a democratic, constitutional government.

Kang introduced the 1908 petition: “Recently, the Court has effected some modest reforms which of course represent an important departure from the conservatism of the past. And yet people grow increasingly anxious and perplexed. This is because a great undertaking [such as reform] can be accomplished only on the basis of honest intention, not of empty promise.” Apart from convening a parliament to form a constitutional government, Kang’s petition called for the retirement of Empress Dowager Cixi and the return to power of Emperor Guangxu;10 retiring the court’s large corps of eunuchs, known for their political intrigue; moving the capital from Beijing to the lower Yangzi River region; modernizing the administration of the country from top to bottom; ending the distinction between the Manchu and Han; creation of a strong navy; and building a citizen army by universal conscription.

Most inflammatory was the demand that the Qing government update the name for China by shedding the traditional form which changed with each dynasty (in this case the Great Qing Empire [Da Qingguo]) and take on a formal name symbolizing unity between the ruling Manchus and the majority Han. Kang proposed the name, Zhonghua, which was eventually adopted by both the Republic and the People’s Republic. Kang wrote:

We humbly request the court to bring up for discussion the elimination of the name and native birthplace registration for Manchus and Han11 and the decision that our permanent country name will be Zhonghua. From the country’s diplomatic credentials to official documents, all will follow this example [using this name]. Since the Manchus, Han, Mongolians, Hui and Tibetans all are governed by the same country, they should all be compatriots of Zhonghua and not differentiated. The Manchu people should be given Han family names too so that they can be assimilated and suspicions and jealousy will vanish forever. This way all groups will be unified to strengthen China. Nothing is better than this in terms of unification and strength.

Kang and Liang, like Liu Xiaobo who was easily vilified by the Chinese government because of his prominence in the 1989 Tiananmen democracy movement, were natural targets for the Qing government. While the thousands of Chinese who signed one or another of the scores of constitutional petitions circulating in China from 1907 to 1911 did so with no response from the Qing court other than rejection of their message, this was not the case with the organizations and newspapers tied to Kang and Liang. They were leaders of a worldwide political enterprise with increasing activities inside China and thus far more of a threat to the government than the smaller groups forming in support of a constitution on Chinese soil.

Chinese autocracies have ever been alert to the dangers posed by their citizens organizing to challenge governmental authority, and the Chinese government’s harsh response to Charter 08 was no exception. The Charter was drafted by a loose group of dissident intellectuals, initially signed by over 300 people, and endorsed by thousands of ordinary Chinese after it was posted online. No organization existed, yet the Charter drafters clearly aspired to more: “We hope that our fellow citizens who feel a similar sense of crisis, responsibility, and mission, whether they are inside the government or not, and regardless of their social status, will set aside small differences to embrace the broad goals of this citizens’ movement.” China’s official news agency Xinhua makes it clear that this is illegal: “The charter also entices people to join it, with the intent to alter the political system and overturn the government. Liu’s activities have crossed the line of freedom of speech into crime.”12 Thus, Liu Xiaobo was convicted of “inciting subversion of state power.” The verdict states: “This court believes that defendant Liu Xiaobo, with the intention of overthrowing the state power and socialist system of our country’s people’s democratic dictatorship, used the Internet’s features of rapid transmission of information, broad reach, great social influence, and high degree of public attention, as well as the method of writing and publishing articles on the Internet, to slander and incite others to overthrow our country’s state power and the socialist system.”13 Although Liu was singled out for harsh punishment as the most prominent signer, many of the other Charter 08 primary signatories were temporarily detained, interrogated, kept from leaving China, or had their activities otherwise curtailed from the time of Liu’s arrest up to the present.

In August 1908, the Qing court had become more and more uneasy with the rapidly growing constitutional petition movement, especially as it showed evidence of increasing organizational effectiveness. Kang’s bluntly-worded petition also seemed to be radicalizing the more moderate constitutional petitioners, who were moved to make more aggressive demands for the opening of a parliament.14 The Qing had to act. However, Kang’s overseas Xianzhenghui was out of reach.

A closer target for the Qing was an affiliated political organization (almost wholly funded by the Xianzhenghui), the Political Information Institute or Zhengwenshe, which had been founded by Liang Qichao in 1907 in Tokyo with the goal of operating openly in China as a moderate alternative to the revolutionaries. In early 1908, Zhengwenshe moved its headquarters to Shanghai, the hotbed of Chinese political activity. By that summer, it had recruited about one thousand members and established provincial chapters, begun to publish newspapers, was reaching out to sympathetic reform-minded officials, and had issued petitions in its own name. No doubt another irritant to the Qing was Zhengwenshe and Xianzhenghui’s joint promotion of the anti-Japanese boycott of 1908, which also criticized the Qing government for acceding to Japan’s humiliating demands following China’s confiscation of smuggled weapons (intended for Sun Yat-sen) found in the Japanese ship, Tatsu Maru. The boycott aroused nationalistic enthusiasm that was easily tied into gathering signatures for the constitutional petition.15 According to Shen Bao, a contemporary newspaper not associated with the Kang/Liang reformers, a group of Qing grand secretaries met to discuss Kang’s petition and devised this strategy:

One of the officials said, our court intends to adopt the constitutional system and is planning to set up a parliament so that Chinese people can participate in national politics. However, we cannot tolerate such an absurd petition because this would lead to chaos. A certain grand secretary said that Xianzhenghui was far away overseas and therefore hard to disband. The coastal provinces had Zhengwenshe branches, and they were connected to Liang Qichao. Why don’t we start with Zhengwenshe? Most grand secretaries agreed. In a few days they made a plan to arrest the members of each Zhengwenshe chapter.16

The decree banning Zhengwenshe charged the organization with “pretending to study current affairs while secretly pursuing the provocation of unrest and harming national security.” Zhengwenshe members “include many who are disloyal and important criminals,” and “if [the organization] is not strictly banned, the larger situation will be undermined.” Local and provincial officials were ordered to ban the local chapters, round up members and punish them.17

Banning of Zhengwenshe and denunciation of Kang’s petition meant that neither Kang nor Liang could return to China to take part in the constitutional petition movement, which became all the more ardent. Popular expectations were overpowering the abilities of the government to respond. Soon the legitimacy of the imperial institution would be challenged beyond repair.

William T. Rowe in his new history of the Qing Dynasty, China’s Last Empire, writes: “Both radical students and professional revolutionaries had played important roles in creating a climate favorable to republican revolution. But the influence of both groups had faded after 1908, and neither group was the direct agent of the revolution. The key role fell to a class of persons who had never been overtly revolutionary but who in practice might have been the most revolutionary of all: the reformist elite.” The reformist elite, wrote Rowe, championed nationalism, economic rights, constitutionalism and representative government. “The tenor of their movement was liberal and moderate, and its vocal leader was Liang Qichao, who persistently argued that an empowering constitution, not a revolution, was China’s most pressing need.”18

The 1908 movement quickly grew in mass and energy and whether or not it was intended, gave a powerful push in toppling China’s imperial system three years later. Even the deaths of the Guangxu Emperor and Empress Dowager Cixi in November 1908 did not derail the constitutional petition movement, and Kang himself submitted a memorial to the new Xuantong Emperor asking that parliament be convened in the autumn of 1910 because of China’s critical situation.19 The petition movement gained momentum when the new provincial assemblies convened October 14, 1909, following the nine-year plan of the Qing court for implementation of a constitutional government. Some newly-minted legislators went beyond their formal responsibilities and formed a nationwide coalition to demand that a national assembly be convened. A new wave of petitions flowed in, with Liang Qichao from Japan encouraging delegations of provincial representatives to submit their petitions in person in Beijing.20 When the national Political Consultative Council (Zizhengyuan) convened in October 1910 in Beijing and voted by acclamation to support the petitions, the scene was described by the court-appointed Council chairman (Manchu Prince) Pu Lun: “The entire assemblage was swept by a storm of joy . . . Princes, nobles, scholars and ordinary subjects all gathered together in one room and, giving expression to the same emotion, afforded a spectacle unseen in China for thousands of years.”21 In October, governors-general, governors, and military commanders from almost every province also began to petition, jointly and separately, for the immediate establishment of parliament and the appointment of a cabinet.

This pressure on the Qing court had an effect and in November 1910, an edict announced that parliament would be convened in 1913, rather than in 1917 as originally planned. At the same time, the Qing ordered all petitioning for parliament to cease and attempted a broad crackdown on the movement.

It was a mistake to clamp down on the very elites, who, because of their moderate views and strategic positions, had been recruited by the Qing to participate in the early constitutional reforms. Elite disillusionment and open defiance of the court’s edicts signaled that the dynasty was on the verge of losing its legitimacy. Reformers were further alienated when the Qing formed a cabinet in May 1911 dominated by Manchus, including five members of the royal family, a clear indication that the Qing court had no intentions of sharing power with the Han majority. At the same time, the anti-Qing, anti-foreign, pro-constitution railway rights recovery movement was galvanizing a broad, nationalistic following, and at the forefront were many of those involved in the provincial assemblies and the petition movement.22

By the autumn of 1911, the tide had turned, led not by revolutionaries but by energized and frustrated provincial assemblymen who would no longer wait to exercise their sovereignty and were transformed into empire-breakers, and the Qing Dynasty lost its mandate to govern.

While the constitutional reformers and their ideological leaders Kang and Liang failed in their quest to renovate China as a constitutional monarchy, the Chinese political environment was profoundly altered by their ideas, largely because they were able to put these ideas in action through their organizations, newspapers, petitions and mass actions (such as boycotts), mobilizing Chinese citizens inside and outside China. By 1908, the Qing government had been gravely weakened, and China was a country in crisis penetrated by foreign powers and burdened by constricting treaties. Kang’s petition described China’s dire situation and the historical context of the petitioners’ political demands:

The power of the nation is declining, and disorder increases each day. We have suffered troubles within and without, and these dangers are waiting for an opportunity to explode. As a country with 5,000 years of civilization, 400 million offspring of the gods and 20,000 li of rich land, if we can become strong by means of improving our government, this will be an incomparable accomplishment. We become very sad thinking that one day we might find ourselves in the same situation as Poland or India and become slaves or like the horses and oxen of other countries. We, as merchants who were born in China but have traveled abroad, receive insults every day. So witnessing the kind of disaster that Poland and India have suffered, we feel empathy toward them, as well as anger and anxiety.

Today, of course, it is China that is challenging the rest of the world, everywhere from Africa to the U.S., and the Chinese government has both the strength and the agility to dampen political resistance from within. Therein lies the starkly different atmosphere from 1908. Charter 08 arose, and even with the international recognition of the Nobel Peace Prize, was quickly suppressed. Under such conditions, one can only wonder how the Charter 08 political movement might evolve beyond declaration to action. Will its adherents someday be able to form associations, publish newspapers, or organize mass protests as did their late Qing precursors? And if the Chinese government someday undertakes significant political reform as did the Empress Dowager after the Boxer Uprising, will it be able to maintain control while satisfying popular demands?

By Jane Leung Larson, independent scholar, Goshen, MA and New York, NY; blog: Baohuanghui Scholarship. Her article, “Articulating China’s First Mass Movement: Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao, the Baohuanghui, and the 1905 Anti-American Boycott,” was published in Twentieth-Century China, November 2007.

Commentary

Feng Chongyi

The primary goal of the 1908 petition and the constitutional government petition movement as a whole was national salvation, preventing China from colonization. The petitioners believed that the political system of constitutional government was the source of national wealth and power; that the Qing government and the political system of imperial autocracy were outmoded as they kept China poor and weak; and that China would be as rich and powerful as the Western powers and Japan when the political system of constitutional government was adopted. The movement was a lost opportunity because the Qing court, instead of easing its legitimacy crisis through fundamental democratic reform, treated leaders of the movement as state enemies and intensified its legitimacy crisis in the years prior to its overthrow in the 1911 Revolution.

The primary aim of the current Chinese democracy movement embodied by Charter 08 is no longer national wealth and power but the protection of individual rights and interests. Charter 08 is a crystallization of liberal ideas developed in China since the 1990s and a political vision for the rights defense movement emerging in China in the 2000s.23 Charter 08 is known by many as the Chinese human rights manifesto as it extols liberal values of freedom, equality, and human rights, regards constitutional democracy as the touchstone for protecting these values and demands implementation of human rights and social security for Chinese citizens.

The focus on human rights in Charter 08 represents the rise of rights consciousness and more sophisticated understanding of democracy in China. The relative isolation of students and intellectuals is identified as a major setback of the 1989 Chinese Democracy Movement.24 In contrast, the main force of the rights defense movement is the mainstream of society, including workers, peasants, businesspeople and professionals rather than students. By providing political and intellectual guidance and articulating social, economic and political demands across all social strata, and by embodying the spirit of justice, peace, rationality and the rule of law, Charter 08 heralds a coalition between intellectuals and the “broad masses of people” and the convergence of social movement and political democratization. Furthermore, the Charter 08 Movement represents a grand alliance of Chinese liberal elements “outside the system” (tizhi wai) and “within the system” (tizhi nei). The principal force of the Charter 08 Movement are those “outside the system”, but the signatories and supporters of Charter 08 also include officials, retired officials, scholars and professionals “within the system”, such as Li Pu, Du Guang, Zhang Sizhi, Mao Yushi, Sha Yexin, Zhang Xianyang, Xu Youyu, He Weifang, Cui Weiping, Li Datong and Li Gongming. Some of the current CCP leaders, Premier Wen Jiabao in particular, also openly embrace the universal values of freedom, equality and human rights and call for meaningful democratic reform.25 Echoing Charter 08 and using milder language more acceptable to Party leaders, 16 senior party members, including Du Daozheng (director of Yanhuang chunqiu, former director of the State Press Bureau and former chief editor of Guangming Daily), Du Guang (former director of Research Office and the Librarian at the Central School of the CCP), Gao Shangquan (President of China Economic System Reform Association and former deputy chair of the State Economic System Reform Committee), Li Rui (former deputy chief of the Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee), Li Pu (former deputy director of Xinhua News Agency), Zhong Peizhang (former director of the News Bureau, the Propaganda Department of the CCP Central Committee) and Zhu Houze (former Party Secretary of Guizhou Province and chief of the Propaganda Department of the CCP Central Committee) presented a petition to the CCP Standing Committee of Politburo on 20 January 2009. Instead of directly spelling out those liberal principles, the petition urges the Party leadership to “guarantee and put into effect the citizen rights stipulated in the Constitution” and “make a breakthrough in reform and opening by overcoming the obstruction of vested interests”. The petition also makes several policy recommendations, such as establishing democratic procedure to guarantee the proper use of the 4 trillion yuan economic rescue package, resuming the program of political reform formulated by the 13th Party Congress, strengthening the independence of supervisory bodies, liberalising the media, and widening the space for the development of NGOs.26 Again, echoing the announcement of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, and in the run-up to the 5th plenum of the 17th Party Congress, 23 former ranking Communist Party members, including Li Rui, Li Pu, Hu Jiwei (former director and chief editor of People’s Daily) and Jiang Ping (former president of Chinese University of Law and Political Science), sent an open letter to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on 11 October 2010, calling for an end to censorship in China. The letter cites article 35 of the Chinese Constitution and demands that the State honor its commitment to freedom of speech and press. It laments that censorship in China has reached such an absurd level as to suppress and muzzle the speech of the head of the Chinese government, Premier Wen Jiabao.27

|

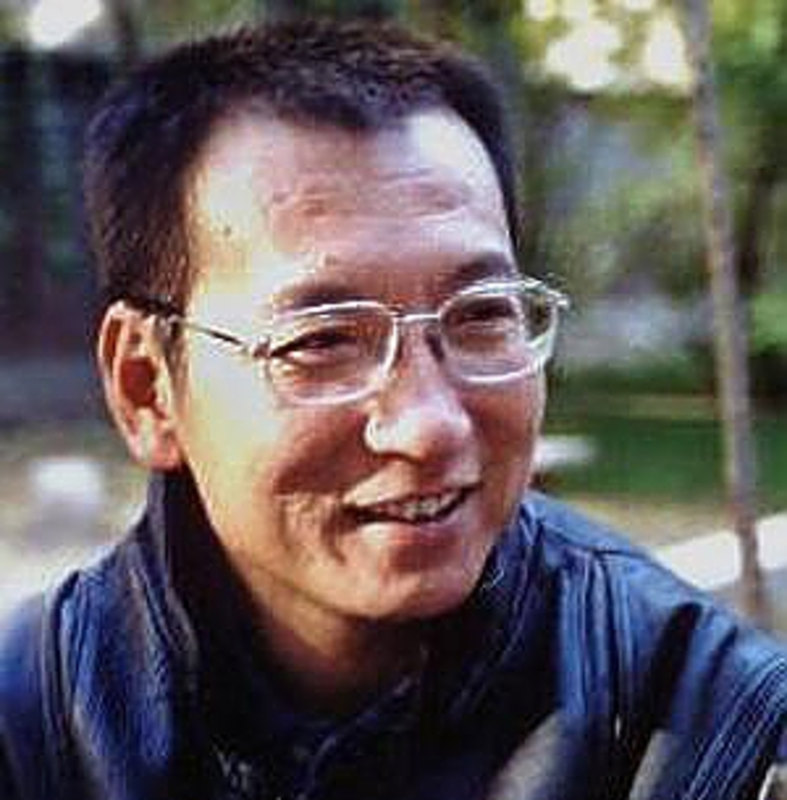

Liu Xiaobo |

The feasibility of China’s peaceful transition to constitutional democracy, as urged in Charter 08, lies as much or more in the aspirations, demands and support of the population as in a decision by the CCP leadership to embrace universal values of humankind and join the mainstream of civilized nations in the contemporary world. As predecessors of the 1908 petition, the drafters and signatories of Charter 08 do not exclude the ruling elite from the process of political transition but invite their participation.

It is unfortunate that the CCP leadership, dominated by the hardliners, has not responded positively to Charter 08 but launched a new round of open attacks on institutions of constitutional democracy and declared an unprecedented war on universal values.28While the thought police led by Li Changchun, member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo in charge of propaganda affairs, has tightened control on liberal voices in the media, the security apparatus led by Zhou Yongkang, another member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo in charge of legal affairs, has stepped up persecution of democracy movement leaders, liberal intellectuals, human rights lawyers and other human rights activists. The communist hardliners, like the conservative Manchu nobility in the waning years of the empire, still seek to maintain permanent autocracy in the guise of “preserving social stability”. They do not see the rights defense movement, the growth of rights consciousness and civil society in particular, as political progress, but continue to see it as a serious challenge to their authority. As a consequence, the party-state and Chinese society are moving in opposite directions. Instead of engaging in positive interactions with the liberal forces and Chinese society to move forward, the party-state has moved backward and upgraded systematic suppression of social and political activism to a higher level since 2008, coupling minimum concessions with cruel crackdowns by the massive repression apparatus. The concessions included an increase of personnel and budget for mediation in disputes and payments for ordinary rights defenders, but the priority was given to comprehensive crackdowns, attacking NGOs, controlling the media and jailing or monitoring a large number of targets in the black lists of the state, such as separatists, Falun Gong adherents, democracy movement leaders, “house church” priests, human rights lawyers, journalists, public intellectuals and petitioners.29 Rights lawyers and NGOs were particularly hard hit in this new round of state repression, which represented a retrogression of Chinese official legal reform and China’s march to the rule of law.30

The Chinese communist autocracy challenged by Charter 08 movement is encountering a legitimacy crisis as was the imperial autocracy of the Qing challenged by the 1908 petition. The quest for the alternative of constitutional democracy by democracy movement and human rights activists, political dissidents and democrats within the Party is a clear sign of this crisis.

However, the legitimacy crisis facing the CCP leadership today is much lighter than that facing the Qing court one hundred years ago. The mainstream of the Chinese communist bureaucracy and strategic groups are still intoxicated with Chinese economic achievement, seeing economic success brought about by reform and opening as proof of the “advantage” of communist monopoly of political power under “market economy”. Charter 08 was easily suppressed by the communist regime without major turmoil. More sadly, if there was a race between top-down reform and bottom-up revolution during the final years of the Qing Dynasty, the race in China today is between top-down reform and total collapse of social order, simply because the communist rulers have effectively prevented the emergence of an organized opposition to establish an alternative democratic order. The Chinese democracy movement led by dissidents has been forced into exile, and the rights defense movement, which involves all social strata throughout the country and covers every aspect of human rights, is unable mount a coordinated nationwide movement but has instead developed as a diverse wave of isolated cases of public interest litigation at courts and public protest in the streets. The “mass incidents”, a term coined by the Chinese communist party-state to describe those unapproved collective actions of strikes, assemblies, demonstrations, petitions, blockages, collective sit-ins or physical conflicts involving ten or more participants, numbered 60,000 in 2003, 74,000 in 2004 and 87,000 in 2005, an average of more than 200 protests a day, according to official figures.31 The number of “mass incidents” in recent years has been estimated beyond 100 thousand annually, but official figures have not been published after 2006 as those figures would show the policy failure of “stability preservation”. Some of these “mass incidents” involved thousands of people and resulted in police and paramilitary intervention leading to loss of lives. Under the slogans “stability overriding everything” and “nipping every element of instability in the bud”, artificial “stability” is imposed by the current Chinese communist regime dominated by corrupt power elite at the expense of justice, reform and progress, leading to more dangerous instability and what is called by Chinese sociologists “social decay” (社会溃败) with serious symptoms such as the structural corruption and a “situation beyond governance” (不可治理状态).32

Feng Chongyi is Associate Professor in China Studies at the University of Technology, Sydney, and adjunct Professor of History, Nankai University, Tianjin. His numerous books in English and Chinese include Peasant Consciousness and China; From Sinification to Globalisation; The Wisdom of Reconciliation: China’s Road to Liberal Democracy and Liberalism within the CCP: From Chen Duxiu to Lishenzhi. He is also the editor of China; and Constitutional Democracy and Harmonious Society.

Recommended citation: Jane Leung Larson with Feng Chongyi, Charter 08’s Qing Dynasty Precursor, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 27 No 2, July 5, 2011.

Articles on related subjects:

• Feng Chongyi, Charter 08 Framer Liu Xiaobo Awarded Nobel Peace Prize. The Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism

Notes

1 “China’s Charter 08,” translated from the Chinese by Perry Link, New York Review of Books, January 15, 2009.

2 Norbert Meienberger, The Emergence of Constitutional Government in China (1905-1908): The Concept Sanctioned by Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi (Bern, Frankfurt am Main and Las Vegas: Peter Lang, 1980), p 91.

3 Robert Leo Worden, “Chinese Reformer in Exile: The North American Phase of the Travels of K’ang Yu-wei, 1899-1909” (PhD dissertation, Georgetown University, 1972), p. 77-78, gives this figure by Kang in 1906 as the most conservative membership estimate and mentions other much higher (and improbable) estimates such as 1 million, given by Kang’s daughter, Kang Tongbi, and 5 million, by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1905. See “Mapping the Baohuanghui” for a chart of the chapters that have been identified, along with schools, businesses, newspapers, women’s auxiliaries, and other organizational arms.

4 Permutations of the name used by Kang, Liang and other members are: Guomin Xianzhenghui, Guomin Xianzhengdang, Diguo Xianzhenghui, Zhonghua Xianzhenghui, Zhonghua Diguo Xianzhenghui, and Diguo Lixianhui.

5 Even in the 1890s, Kang saw the emperor as primarily a figurehead, “sacred but without responsibility” and forming “one body” with the citizens. According to Peter Zarrow, “Monarchical power (junquan) thus virtually disappears in Kang’s reformism.” Peter Zarrow, “Democracy in Twentieth-Century China: Notes on a Discourse,” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 26:1 (March 1999), 124-125.

6 Who are “the people” [min] Kang is referring to? While one might assume that he was referring to the gentry, or to enlightened reformers, we know from Kang’s utopian vision in Datong Shu that he believed in a progression from autocracy to a pure democracy of free and equal men and women, with constitutional monarchy as the transitional stage. With exile, Kang’s political constituency changed from the educated elite of China to a broad swath of overseas Chinese society (largely laborers and small businessmen in North America), and Baohuanghui and Xianzhenghui membership was open to all those who espoused constitutional reform goals. Merchants who were leaders in their communities were most likely to be the chapter leaders, however.

7 “Diguo Xianzhenghui Dahui Yiyuan Xuli” [Procedures for participants in Imperial Constitutional Association plenary meeting] in Gao Weinong, Ershi Shiji chu Kang Youwei Baohuanghui zai Meiguo Huaqiao Shehui zhong de Huodong [Activities of Kang Youwei and the Baohuanghui among the Chinese in the United States in the first part of the 20th century], (Beijing: Xueyuan Chubanshe, 2009), p. 93.

8 Feng Chongyi in “Charter 08, the Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2-1-10, January 11, 2010, noted that overseas Chinese were specifically excluded from inclusion in the original 303 Charter 08 signatories because the drafters feared being branded as “colluding with hostile forces abroad.” However, in tribute to its international inspirations, Charter 08 took its name from Charter 77, Czechoslovakia’s human rights manifesto, and its drafters intended for it to be published on the 60th Anniversary of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration Human Rights.

9 “Haiwai Yameioufeiao Wuzhou Erbai Bu Zhonghua Xianzhenghui Qiaomin Gongshang Qingyuan Shu” [A petition presented by the overseas Chinese members of the Chinese Constitutional Association in 200 overseas cities in Asia, America, Africa, Europe and Australia], reprinted in Kang Youwei’s journal, Buren Zazhi [Cannot Bear Magazine], #4 and #6 [from page 27], Shanghai, 1913. The petition itself was probably written in 1907 by Kang, who gave this date in Buren Zazhi, but it was published by Jianghan Gongbao on July 30-31, 1908, and by other reform newspapers overseas around this time. Versions vary somewhat.

10 In some versions, including the one Kang republished in 1913, this demand is missing. See Kung-chuan Hsiao, A Modern China and a New World: K’ang Yu-wei, Reformer and Utopian, 1858-1927(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1975), pp 243-245.

11 “. . . Manchus were classified differently from Han. They were registered as ‘banner people,’ whereas non-banner people, who were nearly all Han, were generally registered as ‘civilian.’ These classifications were hereditary and essentially permanent.” Edward J.M. Rhoads, Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), p. 35.

12 “Who is Liu Xiaobo,” Xinhua, Oct. 28, 2010.

13 Human Rights in China, translation of Beijing Municipal No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court Criminal Verdict, 12/25/2009 (link).

14 Jung-pang Lo, ed., K’ang Yu-wei: A Biography and a Symposium (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1967), pp 212-213.

15 L. Eve Armentrout Ma, Revolutionaries, Monarchists, and Chinatowns: Chinese Politics in the Americas and the 1911 Revolution (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990), 126-7, and Wu Xianzi, 《中國民主憲政党党史》Zhongguo Minzhu Xianzhengdang Dang shi [Party history of China’s Democratic Constitutional Party], [San Francisco: Chinese Constitutionalist/Reform Party, 1952], 53-56.

16 Ding Wenjiang and Zhao Fengtian, eds., Liang Qichao Nianpu Changbian [Uncut version of Liang Qichao life chronicle]. Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1983, pp 472-473.

17 Chang Yu-fa, Qingjide Lixian Tuanti [Constitutionalists of the Late Ch’ing Period: An Analysis of Groups in the Constitutional Movement, 1895-1911], (Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 1985), pp. 348-361.

18 William T. Rowe, China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 273, 277.

19 Hsiao 1975, p 245.

20 Chang P’eng-yuan, “Constitutionalism in the Late Qing: Conception and Practice,” Zhongyang Yanjiu Yuan Jindaishi Suo Jikan, #18, June 1989, p 110, writes that “under the encouragement of Liang Qichao, the 1,643 provincial representatives demanded the establishment of a formal national assembly right away” and then mentions three successive delegations of provincial delegates that traveled to Beijing to organize petitions.

21 John H. Fincher, Chinese Democracy: The Self-Government Movement in Local, Provincial and National Politics, 1905-1914 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981), p. 169. Prince Pu Lun soon came to be “known as a spokesman for ‘the progressives’,” according to Fincher, but had much earlier shown sympathies with the reformers (including meeting with Baohuanghui members during his 1904 visit to the United States).

22 Min Tu-ki, (Philip A. Kuhn and Timothy Brook, eds.), “The Soochow-Hanchow-Ningpo Railway Dispute” in National Polity and Local Power: The Transformation of Imperial China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989), pp 207-216. Mary Backus Rankin, “Nationalistic Contestation and Mobilization Politics: Practice and Rhetoric of Railway-Rights Recovery at the End of the Qing,” Modern China 28:3:315-331, July 2002.

23 Feng Chongyi, “Charter 08, the Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2-1-10, January 11, 2010.

24 Ruth Cherrington, China’s Students: The Struggle for Democracy, London: Routledge 1991; Merle Goldman, Sowing the Seeds of Democracy in China: Political Reform in the Deng Xiaoping Era, Harvard University Press, 1994.

25 Wen Jiabao, ‘guanyu shehuizhuyi chuji jieduan de lishi renwu he wo guo duiwai zhengce de jige wenti’ (Some Issues with regard to the historical tasks during the initial stage of socialism and foreign policies of our country); ‘Guowuyuan zongli Wen Jiabo da zhongwei jizhe wen (Premier Wen Jiabo’s reply to questions of Chinese and foreign journalists), link; ‘Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao Speaks Exclusively to CNN’s Fareed Zakaria’, 23 September 2010.

26 Feng Jian, et al, ‘Guanyu kefu jingji kunnan kaichuang gaige xin jumiian de jianyi’ (A proposal for overcoming economic difficulties and making a breakthrough in reform).

27 Li Rui, et al, ‘zhixing xianfa 35 tiao, feichu yushen zhidu, duixian xinwen chuban ziyou: zhi quanguo renmin daibiao dahui changwu weiyuanhuai de gongkaixin’ (Carry out article 35 of the Constitution, eliminate the mechanism of prior approval, honour the commitment of the freedom of speech and press: an open letter to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress), link. Premier Wen seems to have caused a deep concern among his colleagues in the Politburo by repeatedly calling for democratic reform and declaring in his interview on CNN that “I believe I and all the Chinese people have such a conviction that China will make continuous progress, and the people’s wishes for and needs for democracy and freedom are irresistible, … … I will not fall in spite of the strong wind and harsh rain, and I will not yield until the last day of my life.”

28 Chen Kuiyuan, ‘Speech at the working forum of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’, Journal of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 2 September 2008; Jia Qinglin, ‘Gaiju zhongguo tese shehui zhuyi de weida qizhi, ba renmin zhengxie shiye buduan tuixiang qianjin’ (Raise high the great banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics and uninterruptedly advance the cause of People’s Political Consultative Conference), Qiushi (Seeking Truth), No.1 2009, link; and Wu Bangguo, ‘Jue bu gao duodang lunliu zhizheng’ (Never practise the multi-party rule by turns), link.

29 Guoguang Wu, ‘China in 2009: Muddling through Crises’, Asian Survey, Vol. 50, No 1, pp. 25–39.

30 Jerome A. Cohen, ’China’s hollow”rule of law”’; Jiang Ping, ‘Zhongguo de fazhi chuzai yige da daotui shiqi’ (The rule of law in China is in the stage of major retrogression’, http://www.gongfa.org/bbs/redirect.php?tid=4037&goto=lastpost

31 Yu Jianrong, Dangdai nongmin de weiquan douzheng: Hunan Hengyang kaocha (Rights defence struggles of contemporary peasants: an investigation into Hunan’s Hengyang), Beijing: Zhongguo wenhua chubanshe, 2007.

32 Sun Liping, ‘Zhongguo de zuida weixian bus hi shehui dongdang ershi shehui kuibai’(The Biggest Threat to China is not Social Turmoil but Social Decay”; Social Development Research Group, Tsinghua University Department of Sociology, “Weiwen xin silu: yi liyi biaoda zhiduhua shixian shehui de chang zhi jiu an” [New thinking on weiwen: long-term social stability via institutionalised expression of interests], Southern Weekend, 14 April 2010, link.