A Reflection on the Osama Bin Laden Killing

Vladmir Tikhonov

The following comment on the killing of Osama Bin Laden, abbreviated here, was first published in Korean in the widely read blog Hangyoreh Sarangbang, in early May, and then translated and published in Japanese shortly afterwards.1 Here the author provides an English version, and adds an introduction briefly surveying responses to the death in South Korea, particularly those of progressive sectors of South Korean opinion. APJ

Introduction

Reactions in South Korea to Osama Bin Laden’s assassination by US troops were mixed. The conservative Lee Myungbak government expressed, as could have been expected, “praise for the US government’s efforts to eradicate terrorism.”2 However, even the arch-conservative Chosun Ilbo daily was much more reserved in its editorial commentary (May 2, 2011). It emphasized that South Korea, by virtue of being a US ally, is directly influenced by the “US government anti-terrorist efforts,” noting that 350 South Korean soldiers, 140 policemen, and 54 reconstruction workers are stationed in Afghanistan. But it also cited Al-Jazeera which saw Bin Laden’s death as the epilogue to just one chapter in terrorism’s history rather than the definitive end to terrorism as such.3 The left-liberal Hangyoreh daily went further, pointing to the “war on terror,” with all the accompanying brutality towards civilians in Afghanistan and elsewhere, as one of the “motors” perpetuating terrorism regardless of Bin Laden’s death. It also focused on the recent democratic revolutions in the Middle East as the possible decisive factor in limiting the socio-political terrain occupied by religious extremists.4 Another left-liberal daily, Kyonghyang Sinmun, equally sceptical, pointed out that the assassination heightened, rather than lessened the threat of new terrorist attacks.5

The triumphalism characteristic of the American mainstream media reactions was largely absent in a response that, in general, may be characterized as “sober” and nuanced. Moreover, liberal media tended to focus on international criticisms of many aspects of the “war on terror” related to Bin Laden’s assassination. Hangyoreh, for example, published on May 6, 2011, an article with the telling title: “’American justice’ – where water-torture or the assassination of enemies is permitted,”6 In addition to worldwide criticisms of the ways in which the US treats suspected Islamic militants, the article cited the opinions of several well-known South Korean academics who were critical of the triumphal celebration of a death of a fellow “living being.” Generally speaking, American actions were an object for critical analysis rather than celebration, even among the mainstream political right.

|

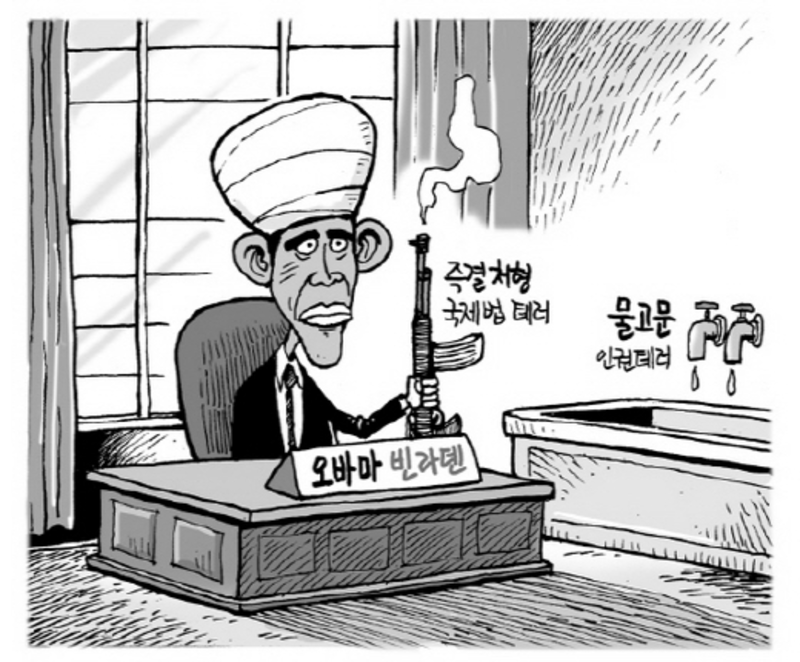

More terror? Hangyoreh cartoon by Jang Bong-kun. U.S. President Barack Obama sits at his office desk with a nameplate “Obama bin Laden,” wearing an Islamic turban and holding an AK-47. The smoking weapon reads, “Summary execution, terror on international law.” Beside the desk a tub reads, “Waterboarding torture, terror on human rights.” |

This sceptical and rather ambiguous mood reflects, to a degree, South Korea’s ambiguous geopolitical standing – that of a military protectorate of the US, which, however, is economically dependent on quickly growing trade with and investment in China, and regards Middle Eastern and Latin American markets as highly promising for Korea’s industrial exports. While US “protection” is seen as an important assurance in dealing with the rival regime in North Korea and with the emerging regional hegemon (China), the routine militaristic excesses of US foreign policy are also viewed as a possible destabilizing factor.

Empire, Law, and Murder

As a general rule in history, the establishment and maintenance of empires, whether it be the Han Empire in the east or Rome in the west, tends to be a story of mass bloodletting. There is no reason why the US empire should be different. The world dominance of American English, the supremacy of Hollywood-produced images of Rambo or Batman, or the US dollar’s position as world’s reserve currency – all these economic and cultural phenomena did not emerge of their own accord. They are underpinned by the Empire’s record of having slaughtered tens of millions of diverse Others, beginning with American Indians and ending with Filipinos, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese and Arabs in the late 19th and throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries, by all means available, including guns, machine-guns, cannons, missiles, “carpet bombing” and atomic bombing.

As slaughter is essential for the all-important business of establishing and maintaining an Empire, it is not simply accepted as a fact of life – it also tends to be relished by the rulers of Empire and these of their “faithful subjects” who have come to internalise their master’s mentality and ways of thinking. After all, they are painfully aware of one simple fact – if not for all the tools of democracy and progress, from the bullets fracturing someone else’s skulls to the Predator-fired missiles pulverizing human bodies in a matter of seconds, they would have never found themselves in the positions they presently occupy. After all, they are not the first-ever imperial people in history to relish slaughter’s sights and sounds. The same feature was present in Rome – where the Colosseum drew cheerful crowds shouting, as if in some orgasmic rupture, at the moment when the sword of a stronger gladiator would penetrate the fallen body of his (or sometimes her) weaker colleague, with a little fountain of blood gushing up from what seconds earlier had been a living human being. For an Empire built by the sword, the weapon does not symbolise death – it symbolises instead the vital force of life.

Even in those days when “US expansion” still meant just further extension of the Frontier rather than establishing new military bases thousands of miles away from the “Homeland”, a death of some particularly “harmful” (read “independent” or “inclined to resistance”) Indian chief might provoke an outpouring of mass hilarity. By World War II, the deaths of the inimical “Japs” came to be celebrated by GIs making souvenirs for girlfriends and parents out of “enemy” skulls or bones. In more vegetarian times after the end of Vietnam War and end of conscription, it started to looks as if celebration of death and destruction at last had come to be limited to more civilized “secondary” methods of enjoying gore – from action films to militaristic video games. But the widely televised mode of popular celebration among at least some segments of American population (which generated doubts and second thoughts even among some relatively conservative US commentators)7 showed that Empire’s grisly ways of celebrating destruction are far from having disappeared.

This outburst of joy over the macabre assassination may appear strange if one remembers that the US, after all, is a paragon of the “rule of law” – and not only at the level of declarations. Its population of lawyers numbers (as of 2007) 1,143,358 – about one fourth of the whole Norwegian population. Indeed, America remains an “empire of litigation.” With “sacred and inviolable” private property given almost divine status and law acting as its guardian angel, American society really hinges upon a reified concept of “law.” Yet neither the President nor the absolute majority of “loyal and patriotic” citizens seemed interested in even a cursory review of the legality of Bin Laden’s liquidation from the viewpoint of international law. Even in a country like the US which retains the death penalty, killing someone “lawfully” requires a death sentence approved by all the higher legal tribunals in cases in which the accused appeals. To be sure, on November 4, 1998, Bin Laden was indicted by United States District Court for the Southern District of New York on suspicion of conspiracy to murder US citizens – but he was never tried, not even in absentia, and was never given an opportunity to defend himself against the accusations levelled at him. And instead of ordering his henchmen to make all possible efforts to ensure that Bin Laden would be taken to the US for a fair trial, President Obama, who holds a doctorate in law, evidently ordered him to be shot in case of even the slightest resistance. In the absence of a formal death sentence, “liquidation” of this sort amounts to state-ordered extra-judicial murder. That, however, did not seem to bother either Dr. Obama or the majority of his – largely law-abiding and very litigious – citizenry.

In addition, Bin Laden was not liquidated alone. Even according to the information provided by his assassins, he was dispatched together with several adult male members of his coterie. One woman and one child, moreover, are believed to have been murdered in the process of murdering Bin Laden. This sort of “collateral damage” is not simply a state-level murder – it amounts to the war crime of “indiscriminate massacre of civilians including women and children.” In fact, formally Bin Laden himself was a civilian too, but, if some violence is to be done to the formal criteria, he may be called a “combatant in the broader meaning of the word” since he subjectively styled himself a “holy warrior.” But even in this case, murdering him, together with some of his underlings and their family members, on Pakistani territory, was a grave violation of Pakistani state sovereignty.

However, these crimes did not seem to be either prevented or even post factum criticized by the system of “checks and balances” supposedly built in to American democracy. Neither legislative nor judicial powers seemed able or willing to do anything to restrain this blatant abuse of executive prerogative. Nor was the conservative-liberal mainstream “free press,” the supposed “fourth power,” any more relevant as a “checking and balancing mechanism.” The most legally-minded nation in the world was largely undisturbed in its media-choreographed outburst of collective joy. How do such things become possible in this empire of lawyers?

In fact, the Bin Laden affair teaches us certain important things about the basic operating rules of the legal system in a thoroughly capitalist society. The law in the US is virtually reified, but reification serves a purpose. The law is really sacred as long as it serves to protect the most sacrosanct value of the capitalist society, its kokutai (the “political essence of the state”, in the parlance of Japan’s pre-war nationalists), namely the holy right of private property.

Bin Laden, originally a CIA-sponsored anti-Soviet mujahidin organizer from the Afghan War (1978-1987), lost any claim to legal protection as soon as he turned his guns against his erstwhile sponsors. Because his activities disturbed the smooth supply of energy to the production centres of American power, protection was denied him.

In conclusion, we can say that this incident served to drive home an important truth – the importance of the law in the US is relative, not absolute. I do not think that South Korea demonstrates any basic difference in this respect. In fact, in the South Korean case, the “relativity” of law may be even more pronounced. Imagine, for example, what would happen in case of a serious armed conflict between the “Samsung kingdom” in the South and the dynastic rule of the Kim family in the North, two equally exploitative regimes, to anyone who either appealed to the Korean public to keep neutral or tried to make use of the conditions of war-time contingency to bring about an anti-capitalist revolution. There can be no doubt that any radical who dared to oppose war in wartime or to issue such an appeal, whether or not it was backed by any sort of action, would be imprisoned or even subject to on-the-spot execution.

Vladimir Tikhonov (Korean name – Pak Noja) was born in Leningrad (St-Petersburg) in the former USSR (1973) and educated at St-Petersburg State University (MA, 1994) and Moscow State University (Ph.D. in ancient Korean history, 1996). He is a professor at Oslo University. A specialist in the history of ideas in early modern Korea, he is the author of Usǔng yǒlp’ae ǔi sinhwa (The Myth of the Survival of the Fittest, 2005) and Social Darwinism and Nationalism in Korea: the Beginnings (1880s-1910s) (Brill, 2010). He is the translator (with O. Miller) of Selected Writings of Han Yongun: From Social Darwinism to Socialism With a Buddhist Face (Global Oriental/University of Hawaii Press, 2008).

Recommended citation: Vladimir Tikhonov, A Reflection on the Osama Bin Laden Killing, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 22 No 2, May 30, 2011.

Notes