Visual Propaganda in Wartime East Asia – The Case of Natori Yōnosuke

Andrea Germer

INTRODUCTION*

Visual propaganda that targeted the home-front in wartime Japan has recently been examined by scholars who have drawn attention to such aspects of material culture as clothing and textiles (Atkins 2002; Dower 2002), postcards and ephemera (Barclay 2010; Kishi 2010; Ruoff 2010) and propagandistic photo magazines (Kanō 2004, 2005; Earhart 2008) that normalize and popularize colonial and militarist policies by way of aesthetic artefacts of everyday use and consumption. Others have examined underlying developments in political infrastructure and mass media as channels of propaganda transmission (Kasza 1988; Kushner 2006). Still other scholars have focussed on visual and other propaganda that targeted Western and later Asian audiences by way of cultural diplomacy by the Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai (Society for International Cultural Relations) affiliated with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Shibaoka 2007; Park 2009) and thereby highlighted the State’s efforts to distribute an alternative image to the militaristic state portrayed in the West, as well as to enhance its image in the occupied territories.

Propaganda in each of the countries that participated in the Second World War varied with its own political structures, cultural roots, creative agents and targeted audiences. While propaganda reception is a generally much understudied subject, it becomes even more difficult to approach in the case of a dispersed and undifferentiated ‘foreign’ (taigai), ‘Western’ or ‘Asian’ audience. In order to successfully sway a foreign audience, however, the creative agent must be versed in the mentalities and cultural expectations of the receiving side.

One of these creative agents in wartime Japan was Natori Yōnosuke (1910-1962), who can be said to have started his career proper with the Manchurian invasion of 1931.

Natori Yōnosuke (1910-1962)

The invasion ignited the interest of foreign media in the subject ‘Japan’, which is why Natori, who was working as a contract photo journalist with Ullstein Press in Germany at the time, was sent to Japan to create an extensive photo documentary. Natori’s photo documentary of Japan laid the groundwork for his international recognition as a photographer as well as making him financially independent. Natori’s various activities after relocating to Japan in 1933 until the end of World War II included producing the photo and design magazine NIPPON (1934-1944), publishing photographs and albums on Japan, the United States, and Germany, developing his ‘workshop’ Nippon Kōbō into a limited company with branches in occupied East and South East Asia, and publishing a number of propaganda magazines financed by the Japanese Imperial Army, Navy and the semi-governmental Society for International Cultural Relations (Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai, KBS). After the war, Natori continued his career as publisher of an illustrated magazine, lead editor of the 286-volume Iwanami Shashin Bunko, award-winning photographer (1953, 1954) and influential photo critic.

Until recently, Natori’s work has been mainly appreciated from the standpoint of aesthetics and design, and he won his highest praise in the context of the history of photography.1 The recollections of Natori’s former students and his staff (the so-called ‘Natori School’), and of colleagues in the postwar worlds of publishing, editing, photography, and design, abound in admiration of their former mentor and boss.2 Another approach to Natori’s legacy started with an exhibition on his photo book Grosses Japan. Dai Nippon (Great Japan, Natori 1937) in 1978, followed by publications that included Natori’s contribution to the wartime regime. The resurfacing of these works helped to demystify Natori’s previously one-sided image as the creator of monumental aesthetic works.3 The reprint of his first illustrated magazine NIPPON (2002-2005) laid the basis for a broader re-evaluation of the political significance of Natori’s aesthetics (Kaneko 2005: 3). Shibaoka’s (2007) erudite study examined the state’s cultural propaganda strategies through KBS and Natori’s involvement, while Gennifer Weisenfeld’s article (2000) shed light on the nexus of tourism and imperialism in NIPPON’s editorial strategies. Lastly, Koyanagi Tsuguichi’s reflections (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993) enabled a closer look at Natori’s wartime political agency in China, for which Shirayama and Hori (2006) provided the visual material. Drawing on the above studies, in this paper, I focus on Natori the photographer and editor-cum-artist from an angle that interrogates his political agency as seen in his creative work and his visual strategies, as well as in his management of the various magazines he edited during the Asia-Pacific War (1931-1945). Moreover, I discuss the extent to which Natori’s legacy of Japanese wartime propaganda has been critically reflected or obscured in his own postwar writings, in those of his disciples, as well as in scholarly literature on photojournalism. While even some of the critical scholarship on Natori shows apologetic tendencies and fails to sufficiently address his agency in the production of wartime propaganda, I argue that Natori’s legacy and its treatment provide a showcase for the unresolved ways of coming to terms with the wartime past in Japan.

THE BEGINNING OF A CAREER IN PHOTOJOURNALISM

Natori was born into a wealthy and influential family associated with the Mitsui Conglomerate and the insurance company Teikoku Seimei. When ‘bad boy’ (furyō shōnen) Natori (2004: 98) repeatedly failed to enter the preparatory school for Keio University, he was sent to Germany to study German at the age of 18. Subsequently, he studied design at an arts and crafts school in Munich and became acquainted with new trends in the emerging field of photojournalism. At the time, the portable, lightweight and high-quality German cameras Ermanox and Leica greatly facilitated the emergence of the profession (Gidal 1972). Natori equipped himself with the newest model compact camera, a 35mm Leica. With the help of his wife and partner Erna Mecklenburg (1901-1979) and his friend Hermann Landshoff, Natori became affiliated first with the Münchner Illustrierte Presse (Munich Illustrated Press) and was later hired as a contract photographer for the competitor of the Munich paper, the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (sic!) (Berlin Illustrated News; published by Ullstein Press) in November 1931.4

Just two months earlier, on 19 September 1931, the Kwantung Army had invaded Manchuria, which could have been one reason for Natori’s employment. Only three months later, in February 1932 and at the age of 22, he was sent to Japan. On his three-month stay in Japan, Natori took approximately 7000 photos on 30 themes, such as Japanese family life, Japanese inns (ryokan), beer factories, geisha schools, Yasukuni Shrine, tea ceremony, festivals, and Germans in Tokyo. According to Natori, photos of this journey had been published at least 270 times by 1939.5 He established his reputation as a photo journalist through this collection of photographs and earned enough money to finance himself for the next 10 years (Natori 2004: 121). Natori’s mission was to present Japan as respectable, modern and at the same time rich in cultural tradition, in order to ameliorate Japan’s international isolation after its withdrawal from the League of Nations (1933) and to work for its international recognition as a ‘normal’ modern nation-state. He worked ‘from home’, so to speak, and only later would travel to China and eventually settle there in order to pursue his propagandistic work of covering up Japanese colonialist and imperialist warfare.

After returning from Japan to Berlin, Natori was asked by Ullstein Press to cover the Japanese Army in Manchuria and he spent February through May 1933 there. When back in Japan for a break, Ullstein informed him that political conditions in Germany had changed such that it was impossible for German media to employ ‘non-Aryan’ staff.6 Nonetheless, they offered him affiliation as a foreign correspondent. Uncertain of the future but financially independent, Natori declined the offer and decided to establish his own business in Japan. The timing was good as the photo magazine Kōga (Photograph) had just been founded the previous year and the photographic avant-garde was looking for ways to express itself. In 1933, Natori thus founded Nippon Kōbō together with photographer Kimura Ihei (1901-1974), designer Hara Hiromu (1903-1986), photo and art critic Ina Nobuo (1898-1978), and the very influential producer, actor and photographer Okada Sōzō (1903-1983; stage name Yamanouchi Hikaru). Supporting members were poet and writer Takada Tamotsu (1895-1952), journalist and critic Ōya Sōichi (1900-1970) and journalist Ōta Hideshige (1892-1994).7

NIPPON KŌBŌ: FROM WORKSHOP TO CORPORATE BUSINESS

The artists and writers who would come to be associated with Nippon Kōbō were interested in the modern trend of ‘new vision’ and the German Bauhaus concept of Neue Sachlichkeit (new objectivity) that was to influence arts and crafts worldwide.They were attracted by the technical and conceptual knowledge of photojournalism, arts, crafts and design that Natori had brought back with him from Germany and they aimed to start a practical movement along the lines of Neue Sachlichkeit in Japan. The first two Nippon Kōbō exhibitions were both successful. The team planned to run a photo news agency to send photographs from Japan to other countries and to produce commercial photo art. Due to differences in thinking and financial difficulties, however, the group that had been formed by professionals on an ‘equal level’ dissolved less than a year after it had been founded. Natori (2004: 137) explained this as ‘a matter of course as this was a group of very strong individuals.’ However, the fact that Kimura, Ina and Hara subsequently founded Chūō Kōbō together suggests that the reason for the break-up was a conflict between Natori and the other members. Natori and Erna Mecklenburg meanwhile re-established the second Nippon Kōbō with new, younger and less experienced staff.

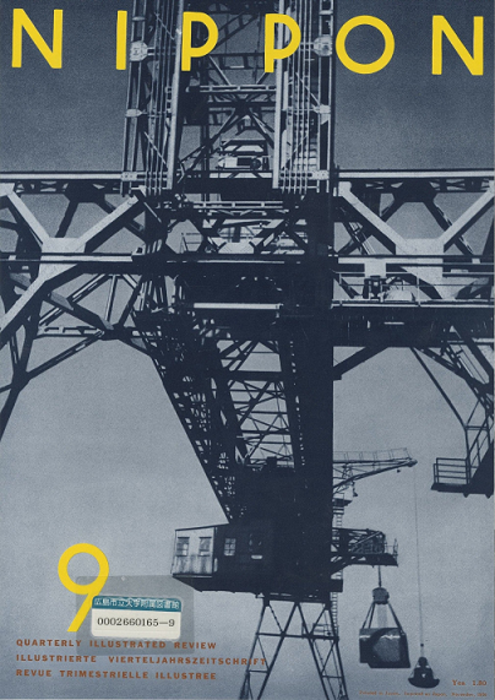

The second Nippon Kōbō published a quarterly illustrated review NIPPON for foreign audiences in English, German, French and Spanish. It appeared in 41 issues, including five Japanese editions, between 1934 and 1944.

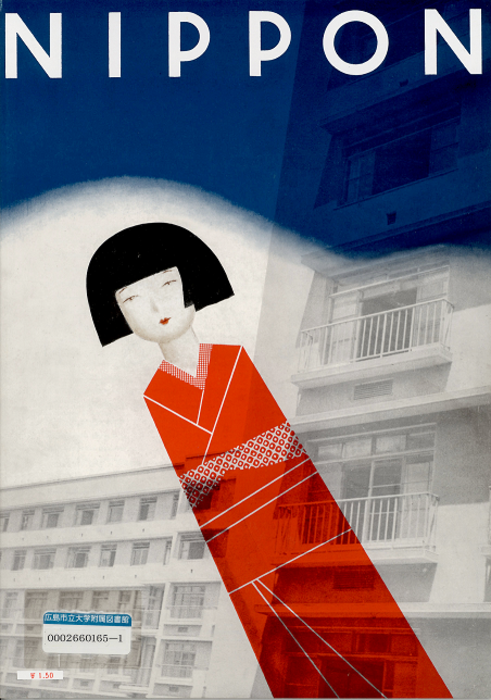

The cover of NIPPON’s first issue (1934) visualises the combination of modernity and tradition, or the West and Japan, through a colourful and highly stylised female paper doll in traditional Japanese attire superimposed on a photograph of modern architecture’s functional style in black and white.

NIPPON claimed to represent ‘actual life and events in modern Japan and the Far East’ (NIPPON 1, 1934).

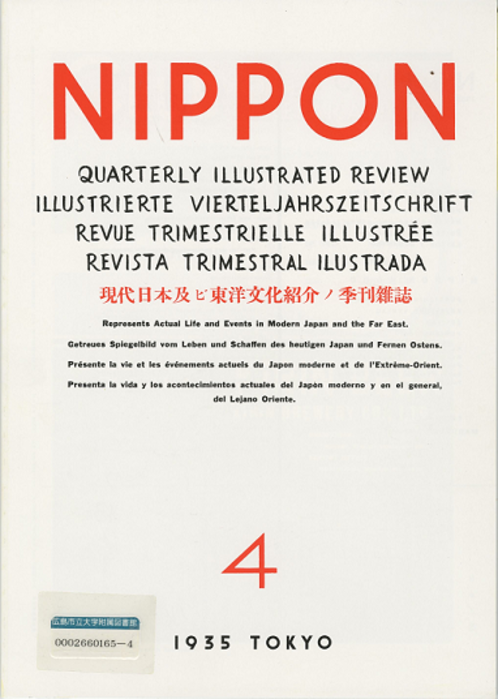

Cover page of NIPPON 4. The claim to represent ‘actual life and events in modern Japan and the Far East’ is a claim for truth and authenticity that is made and asserted on the front cover of the magazine. This is the only issue of NIPPON that does not provide a visual on its cover. All the same, the choice of the colours red and white and the red Japanese title in the centre of the scriptural design refer to the colours and the structural design of the national flag.

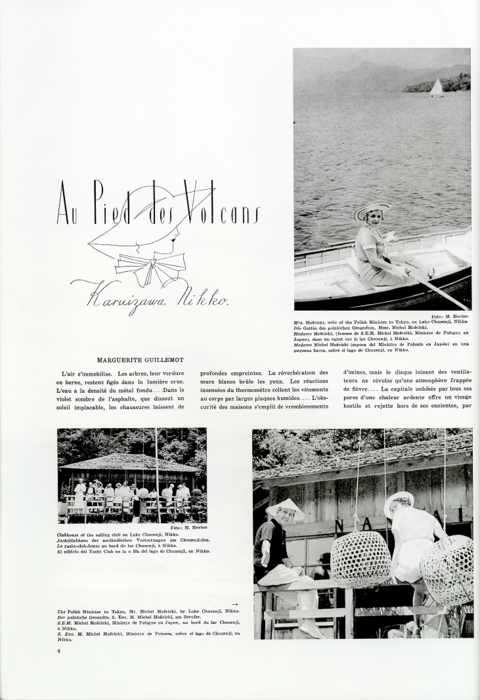

Clearly influenced by the modern trend of ‘new vision’ and Bauhaus aesthetics, it was masterful in terms of layout, design and photography. Rather than a review, however, it was a propaganda tool similar to later propagandistic journals and photo magazines, such as Shūhō (Weekly Report, established in 1936) or Shashin Shūhō (Photographic Weekly Report, founded in 1938) (Kanō 2005: 35, Earhart 2008, Weisenfeld 2005). Natori’s magazine was supported by corporate advertising and by the Foreign Ministry from 1934 (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 91). Its main advertisers were Kanebo, Mitsui and Mitsubishi conglomerates, and various other large companies in printing, insurance, textile, export and technical equipment. NIPPON was thus a state directed propaganda organ, the first of its kind in Japan, reflecting political and financial circles’ anxiety about the isolation that ensued with Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933. The first feature story of the first issue introduced foreign diplomats and their spouses in a ‘private’ relaxed setting during a weekend outing to the hot springs and resorts of Karuizawa and Nikko.

NIPPON 1, 1934: 4-5. These are some of the visuals that appear in a photo story on European, American and Chinese ambassadors and their wives on outings to Karuizawa and Nikko. The visuals depict more women than men and connote a feminised sphere of recreation, culture and friendship that is in stark contrast to the political world of diplomatic affairs.

Thus NIPPON set the stage for presenting an image of Japan that was neither militaristic and aggressive nor quaint and old-fashioned. By visually inviting foreign readers to join Western diplomats and their spouses on their joyful and relaxed trips to scenic spots of the country, it cleverly combined ‘semi-official’ representation with a private, personal, cultural and peaceful context, displaying a community of friends hosted by the Japanese.

Although NIPPON was the product of Natori’s whole team at Nippon Kōbō, his influence as editor, art director, photographer and producer was so overwhelming that according to Kaneko Ryūichi (2005: 2) it reflected the world view of one man and needs to be treated as such. Indeed, neither in Natori’s own writings nor in those of his staff or his disciples is there any indication of pressure or intervention from the magazine’s sponsors. Rather, as Koyanagi repeatedly noted, Natori actively proposed strategies to advertise ‘Japan’, Japanese politics and Japanese products to foreign audiences (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 91-94).

The model for NIPPON was the German magazine Die Böttcherstrasse. Internationale Zeitschrift (The Böttcher Street. International Journal, 1928-1930).8 This magazine assembled high ranking international scholars, artists, intellectuals and politicians and carried völkisch-racist ideas combined with highly aesthetic design, luxurious layout and high quality print. Half cultural review and half advertisement paper (Schlawe 1962: 50), it was financed by the coffee industrialist Gerhard Ludwig Wilhelm Roselius (1874-1943). Natori, together with graphic designer Kōno Takashi (1906-1999) and the editor of the German magazine Albert Theile, produced a model for NIPPON. Natori took this blueprint to the chief executive of Kanebo, Tsuda Shingo, and explained its underlying ideas (Natori 2004: 139). Aware of the low image of Japanese products worldwide, Tsuda fully supported the plan and agreed to finance the first issue of NIPPON.9 In the same way that Roselius’ company Kaffee Hag had become the main sponsor and main advertiser for Die Böttcherstrasse, Kanebo became the main sponsor and advertiser for the magazine NIPPON.

The aim of Natori’s magazine was to present Japan as a country that was not reducible to ‘Fujiyama, cherry blossoms, geisha and maiko [apprentice geisha]’ (Natori 2004: 130), but as one that excelled as a modern nation-state. This aim is repeatedly asserted in the recollections of his staff (Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu 2005). Rather than deconstructing the stereotypes of ‘oriental’ Japan, NIPPON reconfirmed other established tropes such as its unique family system, the high value of tradition and the unbroken line of emperors, and simply added another technically advanced and modern image to it.

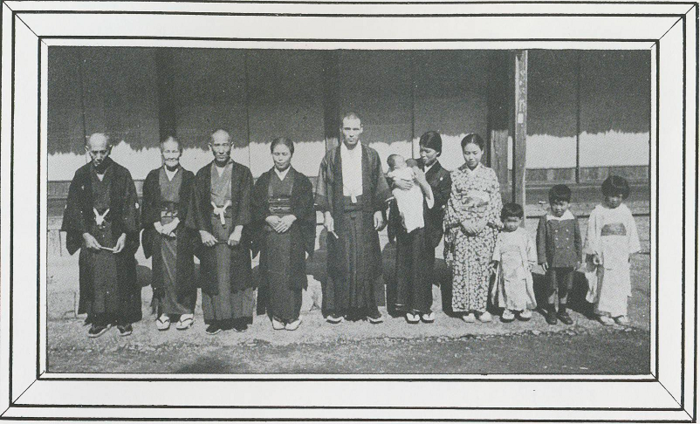

NIPPON 20, 1939: 23. This photograph illustrates the article ‘Family — Base of the Nation’ by Nakagawa Zennosuke. Neither the photographer’s nor the family’s name are noted. In its line-up in traditional Japanese wear with the tall male figure in the visual (though not numerical) centre, it serves to illustrate the concept or essence of the ‘Japanese family’ rather than individual and identifiable people.

NIPPON 9, 1936. The presentation of Japan as an equal technical and commercial partner to the West is emphasised repeatedly throughout the magazine. The close stylistic emulation of Bauhaus aesthetics and ‘new vision’ photography is particularly evident in this photograph.

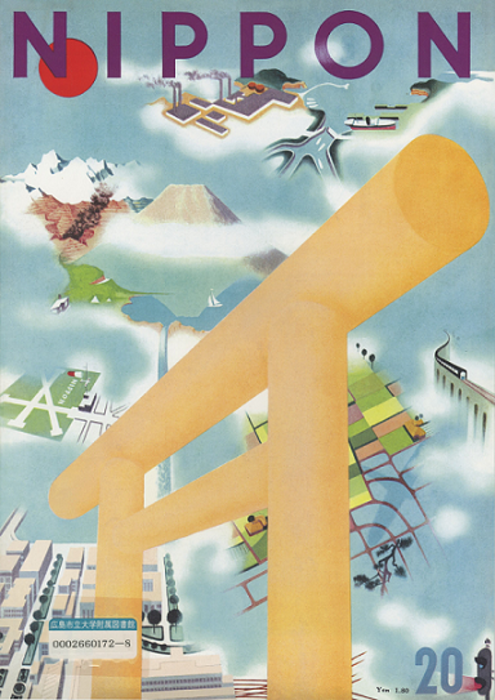

NIPPON 20, 1939, has one of the most densely designed covers. It displays Japan as industrialised with modern land, sea and air infrastructure for commerce and travel, with an intact agricultural sector and scenic rural beauty. Superimposed is a shrine gate that resembles that of Yasukuni but could be any shrine. The image signifies the nexus of Shinto, family, and nation that is visualised and propagated inside the magazine.

As such it promoted Japan as a modern commercial partner as well as an attractive touristic site. As Weisenfeld (2000: 750) summed up, ‘NIPPON was both an attempt by state-sanctioned representatives of the Japanese empire at self-representation and an invocation to the Western viewer to colonize the country through a kind of touristic gaze.’ With its use of montage and captioning – techniques that were also employed at the World Fairs that were covered in NIPPON – it self-reflexively presented ‘Japan-as-Museum’, displaying Japan’s ‘“national strength, national character and national significance” for Western consumption’ (NIPPON 17, 1939: 48; Weisenfeld 2000: 774). Offering ‘a means of “specular dominance” over Japan’ as Weisenfeld (2000: 750) observed, did not, however, imply or engender the panopticist power of the viewer. Rather, the illusion of a specular dominance was created by means of clever, highly elaborate and aesthetic visual compositions that served to veil political interests. Natori, as art director and designer of the magazine, put the utmost care in its presentation. He was also recognized by the government and by the military as an expert in state propaganda and was sought after as a partner in subsequent propaganda strategies.

Natori approached the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Imperial Army to lobby for his project of advertising Japan to the West. While he did not find support from the Ministry at first, Natori (2004: 140) mentioned that it was ‘ironically the Press Unit of the Army Ministry (Rikugunshō no shinbunhan) that showed keen interest’. Soon, however, the civilian government would follow and from 1935 orders for stock photos came in from Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai (Society for International Cultural Relations). KBS was established in April 1934 as an extra-governmental organisation affiliated with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the first organisation of this kind in Japan.10 Natori presumably had already aimed at a sponsorship by KBS, as NIPPON issues 1 and 3 carried articles that introduced KBS in detail (Shirayama 2005: 10-11). Cooperation with KBS intensified after the beginning of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, when Natori became an associate (shokutaku) of KBS. Thereafter, production costs of NIPPON were borne by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Army and the Navy and the inter-Ministerial Information Committee (Gaimushō, Rikukaigun, Jōhō Iinkai) (Shirayama 2005: 15). Japanese officials had discussed using media for war propaganda since the end of World War I, but the Army did not request a ministry of propaganda until 1934 (Kanō 2005), following the Nazi model.11 Natori, because of his knowledge and skills acquired in Germany, can be seen as a forerunner of such direct propagandistic efforts.

The Asia-Pacific War as propaganda war

From the time of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Natori became very busy on two fronts. In Nazi Germany he published a German photo album on ‘Great Japan’ (Grosses Japan. Dai-Nippon) in 1937 (second edition 1942) and organised two exhibits of Japanese arts and crafts there for KBS in 1938. Natori was even more active in occupied China. From his travels to Germany and the United States in 1936-1937 and on an assignment for LIFE magazine, he went straight from San Francisco to Shanghai after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War (July 1937) and spent the rest of the war there. The 1937 October 4 issue of LIFE magazine published the famous press photo by H.S.Wong that became the most influential visual of anti-Japanese propaganda. The photo depicts a crying baby in rags sitting on a platform of the Southern Train Station of Shanghai that had been destroyed by the Japanese Army during their invasion of the city.

After the Japanese bombing of the South Railway Station Shanghai on 28 August 1937. This photograph by H.S. Wong became the most influential visual image of anti-Japanese propaganda.

Koyanagi Tsuguichi (1907-1992),12 who joined Nippon Kōbō in October 1937, suggested that the photo looked staged,13 but reported that everyone at Nippon Kōbō was stunned. Natori commented that the photo was very well taken and an excellent example of Chiang Kai-shek’s anti-Japanese propaganda. He stressed that Japan needed the same kind of photographic propaganda to find allies on the international level, and he told the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Army that he wanted to contribute to the war by making war propaganda (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 93-94). Natori went as far as travelling to visit the Shanghai Expeditionary Army14 where he persuaded the Group Leader of the Special Assignments Unit, Major Kaneko Shunji, that propaganda was needed against Chiang Kai-shek.15 In December 1937, Natori went to Shanghai with Koyanagi to join the Shanghai Expeditionary Army Special Assignments Press Unit. The deal that Natori struck with the Army was that three staff from Nippon Kōbō would be sent to Shanghai to serve as photographers for the Army and that the Army provide three cars and finance a service that would sell photographs to foreign publishers. The photos themselves were to be Nippon Kōbō’s property yet the negatives would belong to the Army (Nakanishi 1980: 231).

Of course, censorship was in effect. Immediately after the China incident, the Home Ministry issued pre-publication warnings. The Army Ministry, the Navy Ministry and the Foreign Ministry also banned items, culminating in so-called consultation meetings (kondankai), the institutionalised feature of top-down press controls that also served to blacklist writers and drive press organs out of business (Kasza 1988: 168-172). Natori, in contrast, took the initiative to serve the interests of the Army in China and actively and creatively pursued cooperation. Within two months in Shanghai, he had set up a press agency ‘Press Union Photo Service’ and proved himself as a professional in the propaganda war. As foreign media were not allowed to accompany the Army, Natori had many requests for visual material from international publishers, which he also provided (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 99).

Camouflaged as a private institution, his press office was in fact completely financed by the Japanese Army. None of the pictures that Natori sold showed any trace of massacres or war crimes.16 Natori himself never went to the battle front, indeed, he reportedly said that he would not go where bullets fly (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 116). He would visit areas the Japanese Army controlled and have himself photographed by Koyanagi. Natori sent these kinen shashin (commemorative photos) off to foreign publishers to convey the impression that he was a frontline reporter (ibid.).

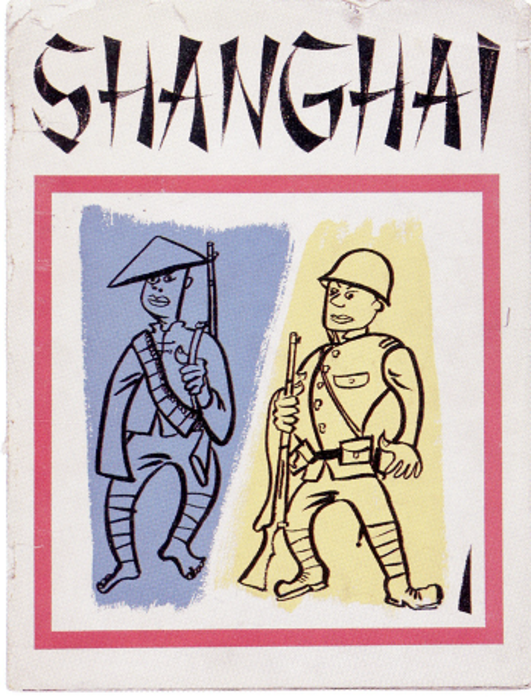

From November 1938, Natori also published the English language magazine SHANGHAI which was distributed in Shanghai.

The magazine SHANGHAI (image in Shirayama and Hori 2006: 82) presented as a Chinese production by a Chinese editor, was actually designed and produced by Nippon Kōbō in Tokyo and fully financed by the Japanese Army.

It was camouflaged as a Chinese cultural magazine produced and published in Shanghai by producer and editor Ching Cong Kan (Nakanishi 1980: 227-228; 1981: 56). In fact, Natori brought photographic material from China to Tokyo and had Nippon Kōbō produce the issues. SHANGHAI is thus a prime example of ‘black propaganda’ that either intentionally falsifies or does not reveal the identification of the sender (Bussemer 2008: 36). It carried the message that Japan brought peace and development to China and that only the Japanese Army could liberate China from communism and from the military clique of Chiang Kai-shek. The financial means for this magazine was provided by the Army Press Unit (Gun Hōdōbu) (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 144-145). Nippon Kōbō editor Iijima Minoru called SHANGHAI an aggressive propaganda magazine (kōgekiteki senden zasshi, quoted in Nakanishi 1980: 228; Nakanishi 1981: 56, 68) and co-worker Koyanagi quotes Natori as proposing that Koyanagi take foreign photographers out to get them drunk while Natori would meanwhile search their rooms for material that could be detrimental to the image of the Imperial Army (quoted ibid.). According to this account, Natori was an active plotter in a conspiracy, not only on the level of profitable and productive cooperation with the Army and KBS, but also on the level of suppressing any evidence that would record a story different from his own propaganda.

By 1944, Natori is said to have witnessed war crimes by the Japanese Army in China (Nakanishi 1981: 82, Shirayama and Ishii 1998: 69). Nippon Kōbō staff and Army photographer Koyanagi also said he witnessed a young Chinese woman who was accused of being a spy being raped and murdered by a Japanese soldier.17 According to some accounts, Natori discussed the wartime state with Japanese intellectuals he invited to Shanghai, wrote a letter of protest (ikensho) against wrongdoings of the Japanese Army stationed in China, and created posters carrying the appeal ‘Don’t burn, don’t steal, don’t rape (yakuna, nusumuna, okasuna)’.18 However, there is no trace of such posters or record of a protest letter. In any event, Natori himself kept silent about his activities in China.

Natori also established branch operations. Around the time of the Canton operation, in September 1938, two more members of Nippon Kōbō were sent to China, this time to the Press Unit of the Army in South China (Nan-Shi Hakengun Hōdōbu) in Canton. There, they established a sister company to the Press Union Photo Service, the South China Photo Service. There, Natori created the English language photo magazine CANTON, which was sponsored by the Army Press Unit and produced by Nippon Kōbō in Canton itself. Natori argued for a similar propaganda magazine in Manchuria and eventually founded the Manchurian Photo Service and the magazine MANCHOUKUO in 1940. The orders from government agencies to Nippon Kōbō increased dramatically between 1938 and 1939, making Natori’s company one of the many businesses that profited from the occupation of China. Kobayashi Masashi, who during Natori’s frequent absences from Tokyo was in charge of several of the new magazines (Kobayashi 2005: 90), called the three years between 1936 and 1938 ‘the golden years of development’ for the team of Nippon Kōbō. In the course of the war, income generated through commercial advertisements decreased while income and activities associated with the newly founded foreign propaganda magazines as well as the number of overseas branches steadily rose.

In an interview published in the photography journal Shashin Bunka in September 1941, Natori stressed that war was not only fought by weapons but also by ideologies, and that photojournalism everywhere expressed national ideology (quoted in Shirayama 2005: 25). Therefore, he said, it does not make sense to copy the West. Instead, Japanese must develop its own photojournalistic expression of Japanese ideas. He went on to stress the need for active expansion and indoctrination in East Asia, maintaining that,

[…] to say ‘we advance to Bangkok’, go over there, take photos and bring them back to introduce them to Japan is not enough. Is not rather the most imminent task for Japanese photojournalists to actively and relentlessly pursue their work in magazines published over there? I really think the only way to do it is for Japanese photojournalists to go over there, install themselves and work from the standpoint of Japanese thinking. (Natori 1941, quoted in Shirayama 2005: 26)

This is precisely what he did, first when he commuted between Tokyo and Shanghai from late 1937, then when he and Mecklenburg relocated to Shanghai in 1940.19 After the outbreak of the Pacific War, Natori would become even more explicit regarding his conviction that Japan should turn away from Western models and aggressively propagate its agenda in its own way in the occupied territories.

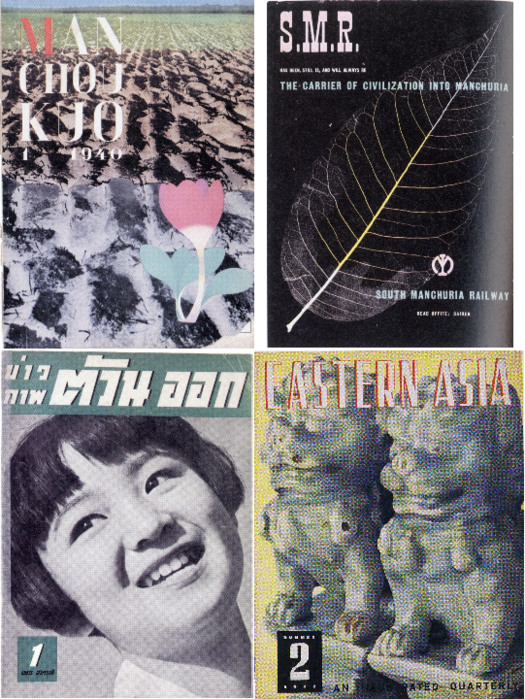

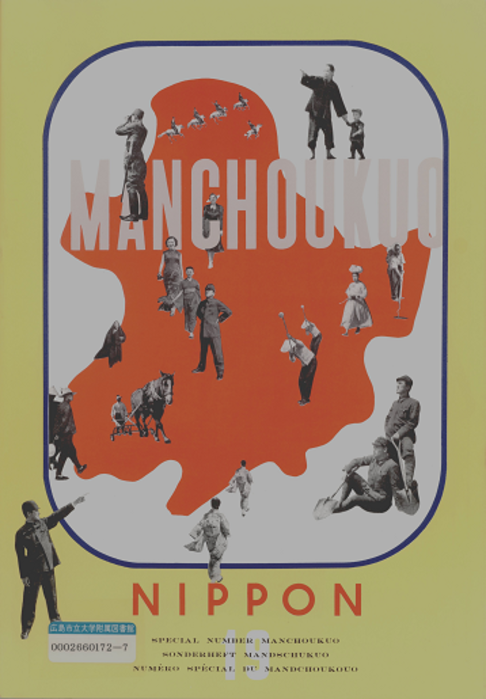

As part of its growth strategy in East Asia, Nippon Kōbō was renamed and restructured in 1939 as a corporation, the Kokusai Hōdō Kōgei Kabushiki Kaisha. Four years later it was renamed the Kokusai Hōdō Kabushiki Kaisha. In 1940, the Tokyo-based firm had branches in Ōsaka, Nanjing, Shanghai, Canton and Shinkyō (today’s Changchun), the capital of the Manchurian puppet state. It employed around 80 photographers and designers, producing several openly propagandistic or ‘propagandistically interspersed’ cultural magazines,20 all of them of high quality and combining arts, culture, photos and illustrations. The magazines Natori initiated and Nippon Kōbō produced were NIPPON (from 1934, KBS, Imperial Army), COMMERCE JAPAN (April 1938, Bōeki Kumiai Chūōkai), SHANGHAI (November 1938, Naka Shina Hakengun), CANTON (April 1939, Nan-Shi Hakengun), SOUTH CHINA GRAPHIC (April 1939), MANCHOUKUO (April 1940, South Manchurian Railways), EASTERN ASIA (1940, South Manchurian Railways), CHUNHA (Naka Shina Hakengun), KAUPĀPU KAWANŌKU [Tōa Gahō, East Asia Picture Post] (December 1941, in Thai language) and others.21

Covers of some of the propaganda magazines initiated and produced by Natori Yōnosuke’s company (images in Shirayama and Hori, 2006: 100-127). MANCHOUKUO’s front cover visually connotes the ideology of the ‘empty’ Manchurian territory, the wide, open, and fertile lands awaiting the Japanese settlers. Its back cover carries an advertisement by the main sponsor, the South Manchurian Railway. The veins of a leaf indicate the railway tracks and traffic infrastructure that signify S.M.R. as the ‘carrier of civilization into Manchuria’, using natural structures to in effect naturalise colonial expansion. S.M.R. also sponsored EASTERN ASIA that propagated the ideology of the ‘Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere’. Published mainly in English, summaries were in French and German, and the captions appeared in all three languages. The propaganda magazine KAUPĀPU KAWANŌKU [Tōa Gahō, East Asia Picture Post] appeared in the Thai language with some English and katakana captions. It advertised Japan and propagated the Japanese advances in South East Asia.

Other press-related companies that Natori established between 1938 and 1944 included a publishing company in Tokyo called Natori Shoten (1940) and a printing company that the Japanese Army had requisitioned in Nanking and for which Natori received the managing rights in 1941, renaming it Taihei Insatsu Shuppan Kōshi (Pacific Press Publishing Company). In Shanghai, he established the publisher Taihei Shokyoku (1942) that produced propaganda publications in Chinese for KBS and the Imperial Army. Apart from magazines, his company designed and produced propaganda photo exhibitions that were presented in China as well as photo albums for the Imperial Army (Jūgun kiroku shashinshū). From 1944, it published Chinese translations of Japanese literature as part of the cultural propaganda strategy. This may have been a product of Natori’s connections to Iwanami Shoten. The Publishing Business Decree, announced in February 1943, effected another round of consolidation in the publishing business (Kasza 1988: 223), including the forced merger of Kokusai Hōdō (and one other company) with Iwanami (Shirayama and Hori 2006: 155). Natori was also asked to run an office in Nanjing for the South China Expeditionary Army Press Unit (1944) as he fervently supported Wang Jingwei’s collaborationist government in Nanjing. In 1944, his company became an officially affiliated organisation of KBS, and Natori thus ran a major organisation for the production of state propaganda (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 146).

‘Manchoukuo’ as propaganda

The Japanese term most often used for illustrated magazines during the 15 year war is senden zasshi, a highly ambiguous term that can be rendered as ‘advertisement magazine’ as well as ‘propaganda magazine’. The term blurs the borders between advertisement, business and politics and at the same time obscures their intimate connections. On the other hand, as Bussemer (2008: 25) noted in his study on propaganda, it is indeed difficult to distinguish propaganda from advertisement, public relations, persuasion, and political communication. Nazi strategies, for instance, attempted to control not only all means of political expression but also non-political popular mass communication for propagandistic purposes – not least in order to suppress older competing discourses in youth and workers’ movements (Bussemer 2005: 56).

The topic of Manchuria lends itself to a clarification of the question of how and when NIPPON developed from an international advertising magazine presenting Japan and Japanese products to an aggressive organ of wartime pan-Asian propaganda. With regard to its political stance towards Japan and East Asia, one can observe a continuum rather than any break in the course of NIPPON’s existence. In the very first issue (NIPPON 1934), Japan’s amicable foreign relations, modern industry, and traditional culture form the overarching themes, and the colonies rather casually appear as part of the advertisement for tea produced in ‘Formosa, Japan’ (p.31), of Kirin Beer‘s branch in Seoul (p.39) and as the scientific examination of the sun’s total eclipse from Lasop Island (part of the Caroline Islands) identified as under Japanese control (p.38).22 In the third issue,

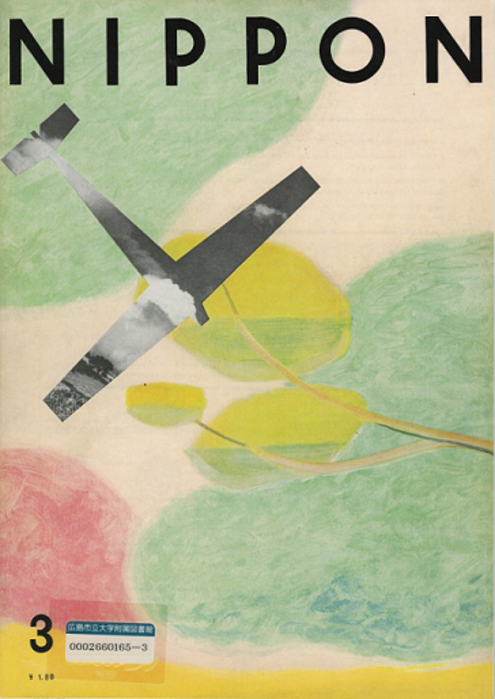

The cover of NIPPON’s third issue reflects the mixed messages that visuals and accompanying texts within the issue convey: Harmonious cultural background in impressionist colours and technological advancement in black and white — Peace and at the same time the readiness for war.

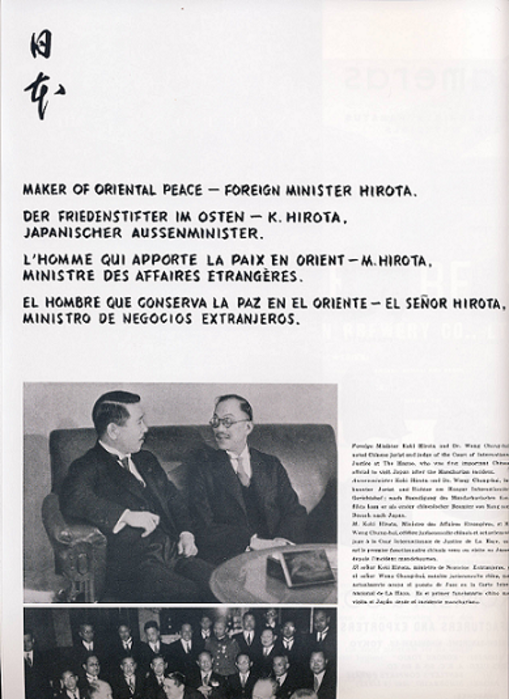

the portrayal of several politicians marks NIPPON as a full-fledged propaganda magazine. Foreign Minister Hirota Kōki (1878-1948)23 is introduced as the ‘maker of Oriental peace’ (NIPPON 1935, 3: 4-5, no page numbers) and Araki Sadao (1877-1966), Minister of War during the Manchurian invasion and supporter of the secret biowarfare Unit 731, authors an article in which he asserts that Japan is the guarantor of ‘peace and humanity’ (Araki 1935: 10).

Foreign Minister Hirota Kōki (NIPPON 3, 1935), ‘Maker of Oriental Peace’

Minister of War Araki Sadao (NIPPON 3, 1935), ‘For Peace and Humanity’.

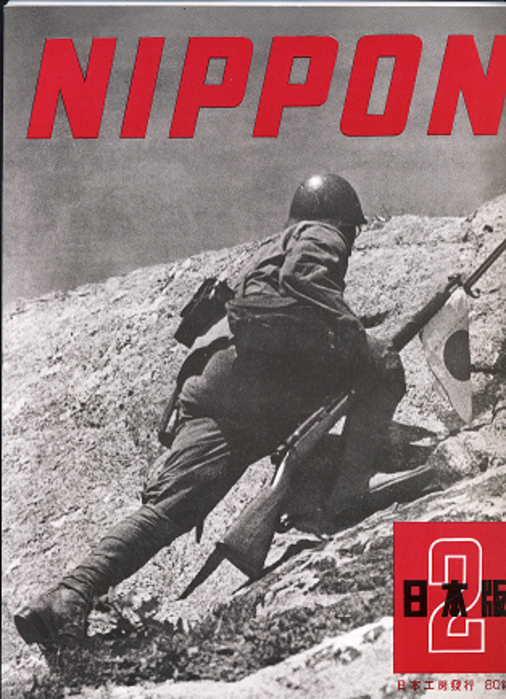

The political tension surrounding the Manchurian puppet state was a major reason for the existence of NIPPON, and NIPPON’s treatment of this state renders it a propagandistic tool from the journal’s very inception. With the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, a belligerent tone takes over and reflects a sense of wartime crisis. While this forms an accommodation to wartime rhetoric, it does not represent a break in the general character of the magazine as a propaganda tool justifying and naturalising Japan’s colonisation in Asia. A Japanese edition of NIPPON had already in 1938 displayed military motifs such as Koyanagi Tsuguichi’s cover photograph of a Japanese soldier in combat in China.

NIPPON, Japanese edition Vol.1, No.2, 1938, photograph by Koyanagi Tsuguichi

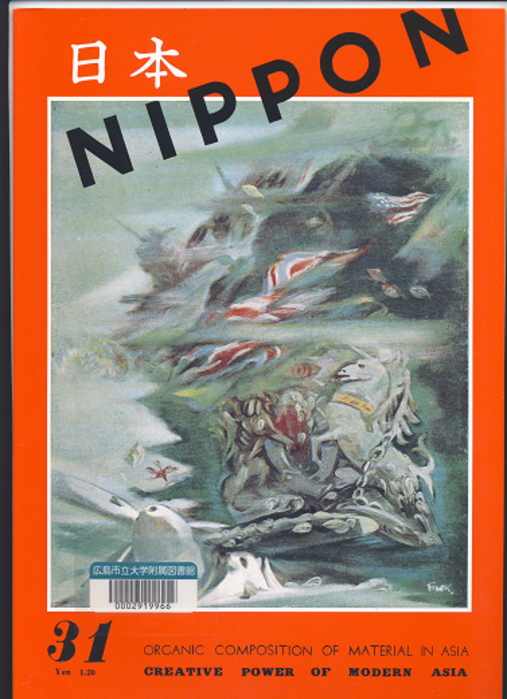

However, the focus on cultural inclusion and appropriation of East Asia remains a marked feature, even after the beginning of the Pacific War and issue No 30 (1942),24 when the articles on military achievements increase and the cover design of every single issue of the foreign languages edition becomes a military- or war-related visual.

NIPPON 31, 1943, Cover

Weisenfeld (2000: 774) amply demonstrated ‘NIPPON’s subtle interweaving of colonial subjects into the fabric of Japan’, and her examination of the collage and photomontage cover25 of the special issue on ‘Manchoukuo’ (NIPPON 1939, 19) brilliantly outlines the imperialist message that the issue transmitted (Weisenfeld 2000: 774-781).

A special issue on ‘Manchoukuo’ (NIPPON 19, 1939)

Both text and image of that issue asserted Japan’s benevolent rule in Manchukuo and the special and harmonious relationship between Japan and the new state. The text stated that, ‘Japan’s assistance toward Manchoukuo is purely that of a friend, there being no such relationship as exists between a principal and a tributary state’ (NIPPON 1939, 19: 16-17, no page numbers printed). Cut-out figures from the interior of the magazine that are identifiable by costume as Japanese, Western, Korean, Han-Chinese, Mongolian and Manchurian are superimposed on an orange map of Manchukuo and visualize a variation of the ideology of the ‘harmony of the five races’ in Manchuria. The composition of the ‘five races’ was not entirely stable. While the official ideology of the five races does not include Westerners, NIPPON’s feature article on agriculture states ‘In Manchoukuo, with Manchurians as the nucleus, the Mongolians, Koreans, Japanese, White Russians and various other races combine in mutual harmony to carry on agriculture’ (NIPPON 19, 1939: 16). The visual and textual inclusion of White Russians can be seen as part of an explicit appeal to Western audiences to accept the Manchurian puppet state. The colours of the Manchurian flag that represent the ‘five races’ are also reflected in a subdued tone in the colouring of the cover montage itself. It is instructive to remember what was not covered in the propaganda magazine NIPPON, such as Unit 731, which began operating in 1932 in the Manchu puppet state (Harris 2002: 37). The Unit tortured and killed several thousand mostly Korean and Chinese political prisoners, POWs and civilians (men, women and infants). It also developed germ warfare that killed several hundred thousand people in East Asia (Tanaka 1996, Harris 2002). Natori and his team were actively reproducing and ‘designing’ the lies that the Japanese Government and Imperial Army invented.

There is an interesting twist particularly in the issue on the Manchu state, which carried mostly material that Natori had brought back to Tokyo from the puppet state. The cover montage’s cut-out figures of various inhabitants and settlers in Manchuria shows only one figure standing outside the frame of the Manchurian map and pointing to it with great purpose. According to Nakanishi (1980: 231; Nakanishi 1981: 62), this male figure wearing the Manchu state’s uniform, the so called harmony-clothes (kyōwafuku), is none other than Natori himself. This staging highlights the production of propaganda as a creative invention of de-contextualised cut-and-paste elements and visually underscores Natori’s personal complicity and active involvement in this fabrication of lies.

POSTWAR CAREER – A NEW BEGINNING OR ARTICULATE SILENCE?

Iizawa Kōtarō’s 1993 history of postwar Japanese photography begins with an account of the personal fate of Natori Yōnosuke and his new magazine Shūkan San Nyūsu (Weekly Sun News). Iizawa’s book illustrates the central position that Natori inhabits in the historiography of postwar Japanese photography and the importance of the so-called Natori School. By the time of Japan’s capitulation, Natori had returned to Nanking. Following an order of the Army, he destroyed his negatives and other material accumulated during the war. The same was done with any compromising material (all except cultural photographs) in the main Tokyo branch. Because Natori had to have an emergency operation and his new wife Tama was giving birth just at that time, it was not until April 1946 that they returned to Japan via Nagasaki. Natori apparently still had the excretion pipe extending from his stomach from the surgery. Nevertheless he resumed his activities straight away, drawing on the old network. With Matsuoka Ken’ichirō (1914-1994) from Sun News Photo Company (San Nyūsu Fotosha) he discussed plans to create a ‘LIFE magazine of Japan’.26 Matsuoka was the eldest son of former Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yōsuke (1880-1946) who had been a major advocate of the Tripartite Pact and President of the South Manchurian Railway. Incidentally, the elder Matsuoka was portrayed by Sugiyama Heisuke (1940: 12-15) in a feature article in NIPPON 24, in which he was hailed for his role in Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations and his foresight in demanding the dissolution of the political parties.

Immediately after the war, a true magazine boom ensued,27 including a host of photo magazines.28 In this context of restarting or newly developing magazines and media, Natori produced Shūkan San Nyūsu (Sun News Weekly). This magazine, which came out on 13 January 1947, was first published in B4 format. It consisted of only 24 pages of poor paper quality and cost 20 Yen. The cover page showed photos taken by Kimura Ihei of three women’s faces in profile next to each other. This differed from the norm for cover portraits, of frontal shots of smiling female faces. It was also unusual that the magazine used horizontal script (yokomoji) instead of the common vertical script. The magazine’s first issue carried an article titled ‘The human population increases with the speed of 2.6 people per minute’ with illustrations, photos, and captions that dealt with the so-called population problem (jinkō mondai). Although 30,000 copies of Shūkan San Nyūsu’s first issue were printed, only 10,000 sold. According to Iizawa (1993: 7), with its political and economic topics it was meant to be a magazine of enlightenment, but the German functional style, layout, and the horizontal script did not meet the expectations of the mass audience it targeted. However, I would argue that Natori was continuing the same style that he had developed before and during the war, in terms of both content and form. The topic of worldwide overpopulation connects to the wartime ideology of Japan as an overcrowded country that needed the ‘empty spaces’ of Manchuria for its surplus population. During the war, Natori had created several magazines to please the Imperial Army and KBS, which financed his propaganda. That the Japanese readership he targeted with Shūkan San Nyūsu was different from the one he had targeted before, and did not appreciate his continuation in style and content, seems hardly surprising. In the eighth issue, the form, style and content of the magazine was changed towards a more popular appearance. Colour photographs, manga by artists Okabe Fuyuhiko (1922-2005) and Nemoto Susumu (1916-2002), and a serial novel by Ibuse Masuji (1898-1993), who had previously contributed to NIPPON, appeared. Nevertheless, the magazine was not successful. Publication stopped after 5 March 1949, the 41st issue.

Shūkan San Nyūsu was a commercial failure but nevertheless highly influential in the publishing industry of postwar Japan, as many writers, photographers, designers and manga artists who had been active during the war published there. This group– the ‘Natori School’ – eventually became very influential and successful in postwar photojournalism and the media economy. Among its members were Koyanagi Tsuguichi, Kimura Ihei, Kojima Toshiko, Miki Jun, Sonobe Kiyoshi, Fujimoto Shihachi, Inamura Takamasa, Nagano Shigeichi,29 Tagawa Seiichi,30 and Kojima Toshiko. The Natori School thus comprised a host of photographers and editors who would shape the postwar Japanese photographic profession, some as professors and presidents of photo societies who would even lend their names to photography awards (Miki Jun award, Kimura Ihei award; Ina Nobuo award).31

Natori himself remained influential in photojournalism and photo criticism. In a debate with Tōmatsu Shōmei (born 1930), winner of the 1958 Japan Association of Photo Critics Debut Prize for ‘Local Politicans’ (Chihō seijika), he criticised Tōmatsu’s photos as having left the realm of photojournalism or hōdō shashin:

Photojournalism values a certain fact (jijitsu) and a certain time (jikan). Tōmatsu has disposed of this high value that photojournalism places in a certain fact. He attempted to move in a direction in which there is no limit to time or location. To put it differently, by his detachment from time and location, he severed his photos from photojournalism.32

Tōmatsu rebutted that he was not of the Natori School and that he did not see himself as a photojournalist in the first place, ‘the heavy feeling (jūryōkan) that is associated with photojournalism [in Natori’s sense] is a thing of the past’ (quoted in Kishi 1974: 83).

A rare debate in photographic circles, the critique of Natori could have gone further. It could have led to question the ‘factuality’ of Natori’s own practice of propaganda photography and could have sparked a discussion on wartime imbrications of the photographic and publishing profession. But it did not. The silences continued. Photographer Domon Ken (1909-1990) who had worked for Nippon Kōbō from 1935 until 1939 and then for KBS started a new movement in postwar Japan with his proclamation of ‘realism in photography’ (riarizumu shashin undō). However, Julia Thomas (2008) critically discusses Domon’s postwar photography as a continuation rather than as a break with his wartime style in that he sought to capture an ‘authentic’ Japan; Kishi suggests that this ‘realism’ was in effect just what photojournalism had always claimed to be, but that Domon wanted to disassociate himself from the kind of photojournalism that was tainted by the smell of the Army.33 Kishi comments that ‘there should be many wartime photographers who will sense an ache in their hearts when they hear the word “photojournalism”’(Kishi 1974: 16), indicating that they might feel shame for their co-operation in the wartime propaganda.

Natori’s lack of reflection about his wartime role in Japanese Army propaganda is extraordinary. In the introduction to his posthumously published book Shashin no yomikata (Natori 2004: i-iii),34 Natori mused about the various advantages that photography had brought him. Full of praise for the limitless possibilities of creating stories by the means of photography, he also cautioned that one can create lies via the assemblage of photos, captions and text. In a chapter titled Shashin no uso to shinjitsu (The lies and truths of photographs), he chose the example of the Hungarian revolt against the Soviets as it was covered by LIFE magazine in 1956.35 While this was certainly a timely example when he wrote (around 1958), he fails to even hint at his own active production of so many lies about benevolent Japanese rule and harmonious co-existence in Manchuria and the rest of East Asia over the many years he spent in China. Nor does he mention his active involvement in destroying an archive of photo material that could have served as evidence for the activities or even atrocities of the Japanese Army in mainland China, some of which Natori may have witnessed himself. Instead, Natori started his discussion of ‘lies’ with the theoretical observations that the technology of photography itself bears ‘major lies’ when it turns the coloured object into black and white or when it reflects a three-dimensional reality in a two-dimensional photograph (Natori 2004: 36-37). He concluded his paragraph on lies by noting that the photographs we see are the result of the triangular relationship of the photographer’s intention, the editor’s choice and the reader’s expectation as presumed by the editor, and that these images are constituted by, as he put it, ‘the lies that they all need,’ making the veiled argument that the photographer and editor were responding to the as-yet-unstated demands of the viewer. (Natori 2004: 45). Hailed as a photographic theory that for the first time takes into account the ‘standpoint of the viewer’ (miru hito no tachiba kara) (Kimura and Inubushi, in Natori 2004: 204), it seems to me that with regard to Natori’s wartime practice of photojournalism, ‘the viewer’ must take an undue share of the responsibility for the choices the photographer/editor makes. In the wartime situation of government-controlled publishing and increasingly severe paper rationing, it makes more sense to exchange ‘the viewer’ with Natori’s financial and political ‘patron,’ the Army and KBS.

Natori’s observations, arguments and examples seem carefully constructed manoeuvres to divert/deflect attention from the role of his own ever-growing business of war propaganda from the late 1930s until the end of the war. The personal agency he displayed in persuading the military, the state (KBS) and the business community of the need for propaganda, and the tools he created, shows that wartime propaganda was not only produced as a result of systematic or fateful structural changes in the wartime bureaucracy but was championed and produced by individual human activity. This leaves one wanting more investigation into these human political decisions, and into the costs, the gratifications and victimisations they involved. With the exception of a very brief mention by former Nippon Kōbō staff Inada Tomi,36 hardly any of Natori’s disciples have questioned his (or their own) role in producing the propagandistic fabrications in NIPPON and other overseas propaganda magazines or assessed their contribution to the wartime regime. Neither do we find one word of regret for recognition of the East Asian victims in this war that, according to Natori (1941, in Shirayama 2005: 25) was ‘also a thought war’ fought with ideological weapons.37 This may be because they were all implicated and chose silence to cover their shame (Kishi 1974: 16; Shibaoka 2007: 137) – it is at any rate indicative of the broader ‘alchemy of amnesia … forgetting atrocities and war crimes’ that Mark Selden (2008) attests not only to Japan but to the war nationalisms of all combatant powers including the U.S. Some have suggested that Natori reflected on his wartime activities by giving up photography for several years after the war and engaging in editorial work instead (Ishikawa 1991: 243; Shibaoka 2007: 137). Yet, this claim does not seem convincing because his years affiliated with the Japanese Army in China were marked more by the creation, editing and management of new propaganda magazines than by his work as a photographer. Rather, Natori’s biographers have abetted the silence about his wartime activities. In Iwanami’s 41 volume series on Japanese photographers, volume 18 on Natori (Nagano 1998) carries an introduction by Iizawa Kōtarō focusing on Natori’s accomplishments as a photographer who understood ‘photographs as signs (kigō)’ (Iizawa 1998: 3).38 The introduction includes only one short paragraph that comments on Natori’s wartime work:

Of course, as editor and art director his talents in dealing with photographs had become conspicuous before [the war], but one cannot deny that unfortunately when all of Japan was swallowed in the great wave of war he involuntarily was made to participate in military propaganda. (Iizawa 1998: 5)

This is indicative of the way in which, against considerable evidence, Natori is repeatedly portrayed as a passive actor, as someone who unwillingly had to go along with the tide of the time and who bears no responsibility for the choices he made. The image and underlying message of passive natural metaphors such as being ‘swallowed in the great wave’ excuses him and at the same time ‘all of Japan’ as victims of a natural disaster. When it comes to wartime agency and responsibility, the otherwise outstanding genius Natori suddenly becomes a passive commoner, one of ‘all of Japan’.

Nakanishi Teruo provides rare explicit criticism of Natori’s political stance:

Natori Yōnosuke gradually drifted away from photojournalism and leaned too much towards propaganda that targeted foreign audiences. He became absorbed with the demands of the time (jikyoku no yōsei) and accommodated his own wavelength too much to the advances of the Japanese Army. The strategy to expand his business by adjusting his wavelength was expressed in the change of format that came about with the reorganisation [of Nippon Kōbō] into [the stock company] Kokusai Hōdō Kōgei [or Nippon Studio, LTD] (Nakanishi 1980: 231)

But Natori initiated this accommodation of his ‘wavelength’ with the advances of the Japanese Army in order to expand his own business. In the same way, Natori’s case must be seen not only as an example of how someone formed a mutually useful connection with KBS and the Army (Shirayama 2005: 30) but of how one individual encouraged this alliance of aesthetics, business, politics and the military to advance the wartime colonisation of China and make a profit.

Natori’s case raises issues of wartime responsibility and of ways of coming to terms with the Japanese imperial, colonial and ultra-nationalist past that are yet to be examined in depth. Placing beauty and aesthetics in the centre of his drive for perfection, Natori not only shared the regime’s colonial and ultra-nationalist goals but initiated and devised propagandistic means of concealing them. While other wartime artists who have become infamous for their art-as-propaganda, such as Fujita Tsuguharu (also known as Léonard Foujita, 1886-1968) in Japan39 or Leni Riefenstahl (1902-2003) in Germany, were repeatedly confronted with their wartime activities, Natori faced hardly any trace of such charges in his lifetime. For one thing, he died young, at the age of 52, in 1962. Also he did not occupy any official position, unlike Fujita, who had served as President of the Army Art Association during the war. In addition, the personal influence of the ‘Natori School’, which started in the 1930s as a network of people who were mostly in their early twenties and who grew to be influential in photography and graphic design in postwar Japan, cannot be underestimated. This group’s own implication in wartime activities would have made it difficult to criticize Natori. Also, Natori’s wartime propaganda primarily targeted foreign audiences and peoples in the occupied countries, and was little known in Japan until recently. But other facts suggest that the photography world was aware of Natori’s wartime activities. It was only in 2005 that the Japan Professional Photographers Society established the Natori Yōnosuke Award for young photographers under the age of 30. Given the fact that other of his contemporaries were honoured much earlier by awards that bear their names, the lateness of the establishment of the Award can be seen as an indicator of the particularly troubled legacy that Natori represented. At the same time, the Award and a number of publications and exhibitions of his work in the twenty-first century indicate the kind of ‘rehabilitation’ that Susan Sontag (1974) diagnosed for Leni Riefenstahl in the 1970s and that Ikeda Asato (2010) described for Fujita Tsuguharu in recent exhibitions in Japan.40 Natori’s rehabilitation may also be indicative of a general intellectual move to a more right-wing political culture in contemporary Japan (McCormack 2010) and a neo-nationalist revival in the context of the US-Japan security relationship (Selden 2008). At any rate, it serves as a showcase for the still unresolved ways of coming to terms with Japan’s ultranationalist and colonialist past.

Andrea Germer is Associate Professor at Kyushu University with previous positions at Newcastle University (UK) and the German Institute for Japanese Studies (Tokyo). She has been conducting research in gender studies, history, visual and cultural studies. She published a book on women’s history in Japan and the lay historian and controversial feminist Takamure Itsue (in German). Essays in English have appeared in Social Science Japan Journal and Intersection. She is currently working on a book project on Visual Propaganda in Wartime Japan and Germany. Forthcoming is also an essay collection, co-edited with V. Mackie and U. Woehr, Gender, Nation and State in Modern Japan.

Recommended citation: Andrea Germer, Visual Propaganda in Wartime East Asia – The Case of Natori Yōnosuke, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 20 No 3, May 16, 2011.

* Acknowledgements. Research for this article was undertaken during my fellowship generously granted by Japan Foundation, 2010-2011. I would also like to thank the editors of Japan Focus, Laura Hein and Mark Selden, as well as Paul Barclay, Yuki Tanaka and one anonymous referee for their invaluable comments and suggestions. I am grateful for discussions on the subject with Ulrike Wӧhr and Yulia Mikhailova and students from Hiroshima City University where I had the opportunity to present a version of this paper in the Special Colloquium Series on 17 December 2010.

Articles on related topics

• H. Byron Earhart, Mount Fuji: Shield of War, Badge of Peace

• Rumi Sakamoto, ‘Koreans, Go Home!’ Internet Nationalism in Contemporary Japan as a Digitally Mediated Subculture

• Asato IKEDA, Twentieth Century Japanese Art and the Wartime State: Reassessing the Art of Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu

• Laura Hein and Nobuko Tanaka, Brushing With Authority: The Life and Art of Tomiyama Taeko

• Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka, Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States

• elin o’Hara slavick, Hiroshima: A Visual Record

• Nakazawa Keiji, Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

• John W. Dower, Ground Zero 1945: Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors

Bibliography

Araki, Sadao (1935): Für Frieden und Humanität [For peace and humanity]. In: NIPPON 3, pp. 10-11.

Atkins, Jacqueline M. (2002): Propaganda on the Home Fronts: Clothing and Textiles as Message. In: Atkins, Jacqueline M. (ed.): Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Homefront, in Japan, Britain and the United States, 1931-1945. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 51-73.

Barclay, Paul D. (2010): Peddling Postcards and Selling Empire: Image-Making in Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule. In: Japanese Studies 30,1 (May), pp. 81-110.

Barthes, Roland (2009 [1957]): Mythologies. London: Vintage.

Boyle, John H. (1972): China and Japan at War, 1937-1945: The Politics of Collaboration. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Bussemer, Thymian (2008): Propaganda: Konzepte und Theorien [Propaganda: Concepts and theories]. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bussemer, Thymian (2005): “Űber Propaganda zu diskutieren, hat wenig Zweck”: Zur Medien- und Propagandapolitik von Joseph Goebbels [‘To discuss propaganda is not very useful’: On Joseph Goebbel’s media and propaganda politics]. In: Hachmeister, Lutz and Michael Kloft (eds.): Das Goebbels-Experiment: Propaganda und Politik. Munich: Deutsche Verlags-Gesellschaft, pp. 49-63 and 118-119.

Dower, John (2002): Japan’s Beautiful Modern War. In: Atkins, Jacqueline M. (ed.): Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Homefront, in Japan, Britain and the United States, 1931-1945. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 93-113.

Earhart, David (2008), Certain Victory: Images of World War II in Japanese Media. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe.

Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu (2005) [NIPPON facsimile supplement].Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai.

Gidal, Tim N. (1972): Deutschland – Beginn des modernen Photojournalismus [Germany –The beginning of modern photojournalism]. Luzern, Frankfurt am Main: Bucher.

Harris, Sheldon H. (2002): Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-up. New York, London: Routledge.

Iijima, Minoru (2005): ‘Nippon Kōbō‘ sōsetzu kara ‘Kokusai Hōdō Kōgei‘ kaisan made [From the start of Nippon Kōbō to the dissolution of Kokusai Hōdō Kōgei]. In: Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, pp. 36-55.

Iizawa, Kōtarō (1993): Sengo shashinshi nōto [Notes on postwar photographic history]. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha.

Iizawa, Kōtarō (1998): Kigō toshite no shashin [Photographs as signs]. In:Nagano, Shigeichi et al. (eds.): Natori Yōnosuke (=Nihon no shashinka Vol. 18).Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp.3-6.

Ikeda, Asato (2010): Twentieth Century Japanese Art and the Wartime State: Reassessing the Art of Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu. In: The Asia-Pacific Journal 43, 2, 10 (October 25), link.

Ishikawa, Yasumasa (1991): Hōdō shashin no seishun jidai: Natori Yōnosuke to nakamatachi. [Photojournalism in its youth: the group around Natori Yōnosuke].Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Kaneko, Ryūichi (2005): ‘NIPPON’ to wa nan data no ka: Fukkokuban kanketsu ni atatte [What was NIPPON? Notes on the occasion of the conclusion of the reprinted edition]. In: Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, pp.2-4.

Kanō, Mikiyo (2004): Sensō puropaganda to jendā hyōshō [War propaganda and gender representation]. In: Jinmin no Rekishigaku 61, 10, pp. 13-24.

Kanō, Mikiyo (2005): Shashin Shūhō ni miru jendā to esunishiti [Gender and ethnicity in Shashin Shūhō].In: Image & Gender 5, 3, pp. 35-41.

Kasza, Gregory J. (1988): The State and the Mass Media in Japan, 1918-1945. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Kishi, Tetsuo (1974): Shashin jānarizumu [Photojournalism]. Tokyo: Dabiddosha.

Kishi, Toshihiko (2010): Manshūkoku no bijuaru-media: Postā, ehagaki, kitte [Colonial Manchuria’s visual media: Posters, pictorial postcards, postal stamps]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan.

Kobayashi, Masashi (2005): Wakai taiyō to akai sekiyō [The young sun and the red setting sun]. In: Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, pp. 78-93.

Koyanagi, Tsuguichi and Ishikawa Yasumasa (1993): Jūgun kameraman no sensō [The war as seen by a photographer in the Japanese Army]. Tokyo: Shinchōsha.

Kushner, Barak (2006): The Thought War: Japanese Imperial Propaganda. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Kuwabara, Suzushi: Sengo gurafu zasshi to… [Illustrated magazines in the postwar period…]. (Link; accessed 11 November 2010).

McCormack, Gavan (2010): Ideas, Identity and Ideology in Contemporary Japan: The Sato Masaru Phenomenon. In: The Asia-Pacific Journal, 44, 1, 10 (November 1), link.

Mikami, Masahiko (1988): Wagamama ippai Natori Yōnosuke [The very self-centred Natori Yōnosuke]. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2005): The Past Within US: Media, Memory, History. London: Verso.

Nagano Shigeichi et al. (eds.) (1998): Natori Yōnosuke (Nihon no shashinka, Vol. 18). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Nakanishi, Teruo (1980): Natori Yōnosuke wa nani o nokoshitaka (6): Chūgoku de Nihongun no taigai senden ni nettchū [What did Natori Yōnosuke leave behind? (6): Becoming passionate for the Japanese Army’s foreign propaganda in China]. In: ASAHI CAMERA 6, pp. 227-231.

Nakanishi, Teruo (1981): Natori Yōnosuke no jidai [The era of Natori Yōnosuke]. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha.

Natori, Yōnosuke (1937): Grosses Japan. Dai Nippon [Great Japan]. Berlin: Specht.

Natori, Yōnosuke (1941): Kao to koe 1 Hōdō shashinka wa kaku aru beshi Natori Yōnosuke hōmon [Faces and voices 1. Photojournalists’ opinion – Natori Yōnosuke]. In: Shashin Bunka, No 9 (September).

Natori, Yōnosuke (1992): Amerika 1937. Natori Yōnosuke shashinshū [America 1937. Natori Yōnosuke photo collection]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Natori, Yōnosuke (2004 [1962]): Shashin no yomikata [How to read photographs]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Natori, Yōnosuke (2006): Doitsu 1936. Natori Yōnosuke shashinshū [Germany 1936. Natori Yōnosuke photo collection]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

NIPPON. Facsimile. 3 Vols (2003-2005). Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai.

Nippon Kōbō no Kai (ed.) (1980): Senku no seishun – Natori Yōnosuke to sono sutaffu tachi no kiroku [Pioneering youth – Records of Natori Yōnosuke and his staff]. Tokyo: Nippon Kōbō no Kai.

Nobuta, Tomio (2005): Natori Yōnosuke san to watashi [Natori Yōnosuke and I]. In: Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, pp.56-62.

Park, Sang Mi (2009): Wartime Japan’s Cultural Diplomacy and the Establishment of Culture Bureaus. WIAS Discussion Paper No.2008-09.

Ruoff, Kenneth J. (2010): Imperial Japan at its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600 Anniversary. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sandler, Mark H. (2001): A Painter of the “Holy War”: Fujita Tsuguji and the Japanese Military. In: Mayo, Marlene J. and J. Thomas Rimer with H. Eleanor Kerkham (eds.): War, Occupation and Creativity: Japan and East Asia 1920-1960. Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press, pp. 188-211.

Sachsse, Rolf (2000): “Dieses Atelier ist sofort zu vermieten”: Von der “Entjudung” eines Berufsstandes [‘This photo studio is now to let’: On the ‘De-Jewdification’ of a profession]. In: Fritz-Bauer-Institut (ed.): “Arisierung” im Nationalsozialismus: Volksgemeinschaft, Raub und Gedächtnis. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, pp. 269-286.

Schlawe, Fritz (1962): Literarische Zeitschriften. Teil 2 (1910-1933) [Literary Magazines.Part 2 (1910-1933)]. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.

Selden, Mark (2008): Japan, the United States and Yasukuni Nationalism: War, Historical Memory and the Future of the Asia Pacific. In: The Asia-Pacific Journal 43, 2, 10 (September 10), link.

Shibaoka, Shinichirō (2007): Hōdō shashin to taigai senden: 15nen sensōki no shashinkai [Photojournalism and propaganda targeted at foreign audiences: Photographic circles and the 15 years war]. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyōronsha.

Shirayama, Mari (2005): Natori Yōnosuke no shigoto 1931-45 [Natori Yōnosuke’s work 1931-45]. In: NIPPON. Fukkokuban bessatsu. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, pp. 5-33.

Shirayama, Mari (2006): Nippon Kōbō o hikiita Natori Yōnosuke [Natori Yōnosuke – Head of Nippon Kōbō]. In: Shirayama, Mari and Hori Yoshio (eds.): Natori Yōnosuke to Nippon Kōbō. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp.vi-xv.

Shirayama, Mari and Hori Yoshio (eds.)(2006): Natori Yōnosuke to Nippon Kōbō [Natori Yōnosuke and Nippon Kōbō].Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten

Shirayama, Mari and Ishii Ayako (1998): Natori Yōnosuke ryaku nenpyō [Short table of life dates of Natori Yōnosuke]. In: Nagano, Shigeichi et al. (eds.): Natori Yōnosuke (=Nihon no shashinka Vol. 18). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp.68-69.

Shirayama, Mari and Motohashi Masayoshi (2005) (eds.): ‘Shūkan San Nyūsu’ no jidai – Hōdō shashin to ‘Natori Gakkō’ [The era of ‘Weekly Sun News’ – Photojournalism and the ‘Natori School’]. Tokyo: JCII Photo Salon.

Sontag, Susan (1974): Fascinating Fascism. In: The New York Review of Books. (Link; accessed 16 October 2010).

Sugiyama, Heisuke (1940): Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka. In: NIPPON 24, pp. 12-15.

Tagawa, Seiichi (2003): Kōkoku wa waga shōgai ni arazu. Shōwa senden kōkoku no senkusha Ōta Hideshige. Tokyo: Heibonsha.

Tagawa, Seiichi (2005): Yakeato no gurafizumu. ‘FRONT’ kara ‘Shūkan San Nyūsu’ e [Graphics of burnt-out lands: From FRONT to Shūkan San Nyūsu]. Tokyo: Heibonsha.

Takenaka, Tomi (2002): Nippon Kōbō no omoide [Remembering Nippon Kōbō]. In: Fukkokuban NIPPON geppō, dai 2 ki-November 2002, no page numbers.

Tanaka, Yuki (1966): Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II. Boulder: Westview Press.

Thomas, Julia A. (1998): Photography, National Identity, and the “Cataract of Times”: Wartime Images and the Case of Japan. In: American Historical Review, 103, 3 (December), pp. 1475-1501.

Thomas, Julia A. (2008): Power Made Visible: Photography and Postwar Japan’s Elusive Reality. In: The Journal of Asian Studies, 67, 2 (May), pp. 365-394.

Watanabe, Yoshio (1977): Shinbi no anguru 6 [The angle of true beauty 6]. In: Niigata Nippō, Evening edition of May 9.

Weisenfeld, Gennifer (2000): Touring Japan-as Museum: Nippon and other Japanese Imperialist Travelogues. In: positions 8, 3 (Winter), pp. 747-793.

Notes

1 See for example the commentary articles in Natori’s photo albums that were published posthumously, Amerika 1937 (Natori 1992); Doitsu 1936 (Natori 2006) as well as Iizawa (1993, 1998) and Ishikawa (1991).

2 See Nippon Kōbō no Kai (1980), some of these are reprinted in the separate volume with commentaries on the reprinted edition of NIPPON (Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu 2005); see also Ishikawa (1991).

3 See Nakanishi Teruo’s article (1980) and book (1981), Mikami Masahiko (1988) as well as a monograph by Koyanagi and Ishikawa (1993). Recently, Shirayama Mari (2005, 2006) has provided a closer examination of the trajectory of Natori’s artistic and political career.

4 This meant that Natori’s income would depend on the photo stories he could produce and sell which at first left Natori and Mecklenburg who had given up her post in Munich in an extremely tight financial state (Natori 2004: 115-117).

5 Natori in the article Hōdō shashin dangi 3, (in: Kamera, April 1952) quoted in Shirayama (2005: 6).

6 In October 1933, Joseph Goebbels’ ‘Schriftleitergesetz’ (Journalists’ Law) § 5,3 stipulated that ‘only those who are of Aryan decent and not married to a non-Aryan spouse’ were allowed to work in the journalistic profession. The Law went into effect 1 January 1934 (Sachsse 2000: 274).

7 See Natori (2004: 131). Okada helped establish the publisher Tōhōsha, which produced the propaganda magazine FRONT. Ōta would later also contribute to this propaganda magazine (Tagawa 2003).

8 The magazine was published by the Angelsachsen Verlag in Bremen. Its name derived from the street Böttcherstraße in which coffee industrialist Gerhard Roselius bought the houses in a street and then turned them into an open air museum. It included the house of Paula Becker-Modersohn.

9 With a print runof 10 000, Natori (2004: 140) estimated production costs of 6000 to 7000 Yen, which proved to be far too low.

10 On KBS see Shibaoka 2007: 77-89. The successor to KBS in postwar Japan is Japan Foundation (established in 1972).

11 The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda or Propagandaministerium) was the Nazi ministry dedicated to enforcing Nazi ideology in Germany and regulating its culture and society. Founded on 13 March 1933, the ministry was headed by Dr. Joseph Goebbels and was responsible for controlling the press and culture of Nazi Germany.

12 Koyanagi became a photographer of the Imperial Army Press Unit just three months after joining Nippon Kōbō in 1937 and served from the beginning of the Sino-Japanese War throughout the Pacific War. He was one of the few who was not primarily dispatched by a newspaper or magazine publisher but directly served the Japanese army in China, Manchuria, the Philippines and various places in Japan (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 19).

13 Koyanagi mentions that he met H.S. Wong after the war and asked him straightforwardly whether the photograph was staged. He reports that Wong simply answered the question with a smile (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 94). For a discussion of the ongoing dispute on the authenticity

of the photograph see Morris-Suzuki (2005: 72-74).

14 The Shanhai Hakengun was renamed Naka Shina Hakengun (Central China Expeditionary Army) in February 1938.

15 See Koyanagi and Ishikawa (1993: 94). Natori asked Koyanagi to accompany him to Shanghai and for the first three months there, they joined the Japanese Army without pay, as Natori thought he had more freedom in taking pictures if he stayed independent. However, later, Koyanagi earned around 120 Yen per month from the Army (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 98).

16 Koyanagi took the pictures while Natori selected the material for sale. Koyanagi’s photographs did not document the Nanking massacre. Photographs of war dead or war injured were off limits for both international and domestic use as it was assumed that they would weaken the fighting morale of the home front (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 100). Some of the photographs later reproduced in Koyanagi’s book of 1993 had been censored at the time, such as a visual of soldiers praying at the graves of their comrades who died in China (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 62-63).

17 The questions remain whether Koyanagi took pictures of this incident since at least the killing of the woman was something he witnessed (Koyanagi and Ishikawa 1993: 122).

18 For reference to the posters see Nakanishi (1981: 83), Mikami (1988: 304-305), Shirayama (2006: xiv), Shibaoka (2007: 129-130).

19 Erna Mecklenburg‘s expertise in design and bookmaking and her cooperation in the creative projects and organisation of Nippon Kōbō are repeatedly mentioned in the reminiscences of former Nippon Kōbō staff (NIPPON bessatsu 2003-2005). Her particular role and contribution during Natori’s time in China is unclear.

20 Examining Goebbels’ ideas on propaganda, Bussemer (2005: 55) notes that popular media and seemingly non-political popular culture that met the tastes of mass audiences were used to stabilize the political system and the result was a ‘propagandistically interspersed popular culture’.

21 See Nobuta (2005: 60) and Koyanagi and Ishikawa (1993: 146). For listings see the tables in Nakanishi (1981: 126-127), Shirayama and Ishii (1998: 68-69), Mikami (1988) and Ishikawa (1991: 252-253). A detailed annotated chronological listing with visuals is provided in the exhibition catalogue Natori Yōnosuke to Nippon Kōbō 1931-1945 edited by Shirayama and Hori (2006).

22 After the defeat of the German Empire in World War I the German colony Caroline Islands was occupied by the Japanese Navy in 1914 and formally handed over to Japan as a Class C League of Nations Mandate to administer in 1920. The Mandates themselves were a cover up for the division of the spoils of war between the major powers. In violation of the Washington Naval Treaty, Japan began with the construction of military sites on the islands in the 1930s.

23 Hirota can be counted as a member of the expansionist camp in the Second Sino-Japanese War (Boyle 1972: 44).

24 The size of NIPPON changed from A3 to A4 with issue 29 (1942), an issue depicting the map of East Asia with the tracks of ‘The Greater East Asia Railway’ and carrying a photo essay on Japan’s youthful and vigorous Air Force.

25 The cover was designed by Kamekura Yūsaku (NIPPON 19, 1939: impressum; Nakanishi 1980: 230; Weisenfeld 2000: 775).

26 See Iizawa (1993: 9) and the introduction to the exhibition on Shūkan San Nyūsu (in 2006) found here, accessed 10 November 2010) and Shirayama and Motohashi (2006) for the exhibition catalogue. LIFE magazine can be said to have been the model and aspiration of many popular magazines that were established in Japan in the immediate postwar period. The layout and contents of the magazines Hōpu (Hope, first published January 1946) or Asahi Gurafu (Asahi Graph, first published July 1948) are seen to be particularly close emulations of LIFE (Kuwabara Suzushi; accessed 11 November 2010).

27 The new magazine Shinsei (New Life) published in November 1945 sold out within three days. In 1946, the magazines Fujin Gahō, Bungei Shunjū, Chūō Kōron, Kaizō and others were published again, while Sekai, Tenbō, Chōryū, Heibon and others were newly founded (Iizawa 1993: 3).

28 In January 1946, Kamera (Camera) was re-published and the first issue was completely sold out. It had started in 1921 and was targeted at an amateur photo audience. When it was published again in the postwar, it advertised itself as a magazine that was now able to publish under politically liberated conditions. 1946 also saw the publication of Sekai Gahō (World Illustrated), which was a continuation of the prewar magazine Gurafikku (Graphic) with its focus on photo documentaries. Asahi Kamera (Asahi camera), which targeted amateur art photographers, was re-published in 1949 (Iizawa 1993: 4-5).

29 Nagano (1998) is one of the editors of the album on Natori (vol. 18 of the Iwanami series on Japanese photographers).

30 Tagawa previously worked for the propaganda magazine FRONT that appeared between 1942 and 1945 (altogether 10 issues). He wrote a book on his experiences in which he maintains that the expertise gained while producing propaganda was still valuable today (Tagawa 2005).

31 See Iizawa (1993: 8) and the exhibition Shūkan San Nyūsu no jidai: Hōdō shashin to Natori gakkō (The time of Shūkan San Nyūsu: Press photography and the Natori school) in Tokyo in 2006 (Link, accessed 6 October 2010)

32 See Natori (1960) in the October issue of Asahi Kamera, quoted in Kishi (1974: 81).

33 See Kishi 1974:16; on postwar discussions on ‘realism’ in Japan’s photographic circles with particular attention to Domon Ken and Kimura Ihei, see Thomas (2008).

34 The posthumous publication is based on Natori’s writings, mostly from the postwar period. Collected and arranged by Kimura Ihei and Inubushi Hideyuki into a loosely connected text of book format, the compilers concede that had Natori lived to see the compilation he might have corrected and added to the format (Natori 2004: 204). Therefore, the silences of this book may to some extent be also the product of, or concurrent with, the silence produced by the specific choices that the compilers made.

35 While the photos in the LIFE report showed mainly Soviet forces and members of the Hungarian Security Police Force as victims of Hungarian rage over the invasion, the photos along with the captions and the explanation were read as the cruelty and pain that communists inflicted on another people (Natori 2004: 31).

36 In the collection of commentaries published with the reprints of NIPPON (Fukkokuban NIPPON bessatsu, 2005), only one member of the team, Takenaka [formerly Inada] Tomi, points briefly to ‘the lies’ that Nippon Kōbō reproduced with regard to Manchuria (Takenaka 2002: no page numbers). Incidentally, this editorial staff member was, apart from Mecklenburg (and two contract translators), the only female editorial staff in the young boys’ network. Rather than pointing to a sexual differentiation in the capacity to face up to one’s past, I assume that she had a greater distance from her work because she left Nippon Kōbō when she married in 1945 and did not pursue a professional career in the postwar publishing business. Watanabe Yoshio, another previous Nippon Kōbō staff unable to continue a professional career after the end of the war commented of his involvement in propaganda in 1977, ‘that I co-operated with the regime – albeit not actively but indirectly – remained somewhere at the bottom of my consciousness and, spending my days depressed and suicidal, I did not feel like working again’ (Watanabe 1977 quoted in Shibaoka 2007: 137).