Communities Struggle to Rebuild Shattered Lives on Japan’s Coast

David McNeill in Rikuzen-Takata, Iwate Prefecture

Kanno Mitsuhide (36) is standing on a pile of muddy firewood where his home used to be. He has come to salvage what he can and found a single object: a hibachi, a traditional Japanese charcoal heater. “We could only locate the house because of this,” he says, pointing at an old green water pump still clinging stubbornly to solid ground. The small family car is 200 meters away, upside down, across the ruined landscape of Rikuzen-Takata.

|

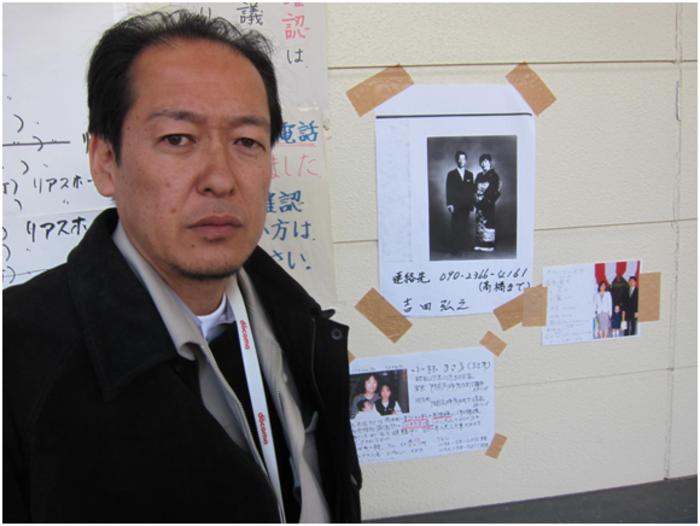

Kanno Mitsuhide (left) stands where his home used to be. (All photographs by David McNeill) |

A few days ago, Mr. Kanno gave up the search for his father, Ken (68), who was washed out to sea. “We think he was in his car, trying to reach relatives when the tsunami came,” he explains. “Everybody ran up there,” he says, nodding up toward a temple. His mother has gone to the local makeshift morgue to identify the bloated, partly decomposed body of her husband. A few days ago the police showed her the wrong corpse. “She was terribly upset.”

Rikuzen-Takata until recently was a picturesque fishing town boasting a 900-year-old festival of floats and a coastline bathed in the azure blue Pacific waters. Today it exists only in name. The quake and muddy deluge has torn the town from its roots, leaving a gaping wound of smashed cars, pulverised wooden houses and twisted metal girders. Car navigation systems still direct visitors to the post office and the local government building, which are no longer there.

|

Mayor Futoshi Toba of Rikuzen-Takata |

Across the town, and up and down Japan’s ruined northeast coast, families like the Kannos are sifting through the wreckage of their lives. The human suffering is almost overwhelming: 27,600 people dead or missing, perhaps 300,000 left homeless, sleeping on the floors of school gymnasiums and sports centers. Of the roughly 23,000 people who lived in this town before the Pacific plates shifted on March 11, 2,400 are dead or presumed so, says Mayor Toba Futoshi, who surveys the ruins from his makeshift offices in Disaster HQ on a hill above the town. Among the missing townspeople is his wife.

“I’m human too, a husband and a father of two,” he says, rubbing a hand over his unshaved face. “Of course it’s difficult. I’ve asked myself if I shouldn’t be out searching for my wife. But I’m no worse than many of the people around me and sometimes better off. Everybody is putting their own feelings aside and working for us so I must do the same. We have one man here, a fireman, who lost his two children, his father, mother and wife. He is the only one left.”

About 400 of Rikuzen-Takata’s homeless can be found in the Daiichi Junior High School a few hundred meters from Toda’s office.

|

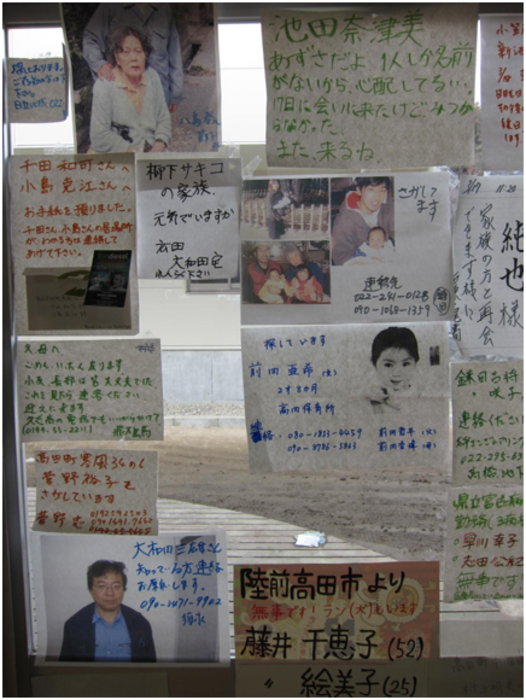

Missing person’s wall in refugee center, Rikuzen-Takata |

The refugees have divided up the school’s huge gymnasium into blocks replicating their old neighbourhoods, marked with handwritten signs and separated by cardboard boxes. Shoes are neatly lined up outside the makeshift homes. Old people doze, bored youngsters read comics, legs dangling in the air, their lives in limbo.

|

In a couple of weeks, the school must be handed back to its students, scattering this community across the region to hotels, ryokans and temporary shelters. |

Many are bereaved and few have insurance to rebuild their homes. “I lost my mother, father and younger brother,” says Sasaki Yurie (42), face wet from crying behind a pollen mask. Her teenage daughter sits beside her, eyes cast downwards. “Everything is so dark right now. We don’t know where we’re going to live, or if the prefecture (government) will help us. Families are going have to support each other financially, but ours has no money.”

Older children will have to look after younger children. Adults will move in with parents or grandparents, if they still have them, explains Fujino Naomi (42), who survived the tsunami with her mother. “My father is missing,” she says. “His body will never be found. It’s ok – I don’t want to see it.” Many people in the gymnasium will have to go into debt to rebuild, she predicts. Some can remember the May 1960 wave that destroyed houses too.

After millennia of quakes and tsunamis the fear of what the ocean can bring runs deep among people in fishing towns all along the northeast. Thick reinforced concrete walls dot the coastline. “We thought we were safe,” says fisherman Nakajima Kenji, standing on the rubble of his home in the village of Sakihama, 30 minute’s drive from Rikuzen-Takata. Behind him is a 10-meter high wall, blocking the sea.

|

Nakajima Kenji on the rubble of his home in Sakihama. |

“I couldn’t believe it when I saw the water coming over the barrier. It was 15 or 20 meters high. I ran for my life.” His wife Miwa stops sifting through the rubble to lift her head. “Another tsunami will come in 50 or 60 years. We’ll be dead but our son will be alive. I’m not coming back here.” Her husband says they’ve already argued. “I want to rebuild here, with concrete, but my family is against it.”

Mayor Toba coordinates housing the homeless from Disaster HQ, crowded with hundreds of people and soldiers. Over 3,600 buildings in Rikuzen-Takata were swept into the sea, including many apartment blocks; about half the rest are partially or irreparably damaged, leaving over a third of the townspeople homeless. In front of the school, 200 temporary 30-square-meter homes are already almost built, the first of 40,000 to be erected all across the three hardest-hit prefectures of Miyagi, Fukushima and Iwate. The agonising calculus of who will get this scarce resource has already begun.

The elderly, the physically disabled and women with children will be allocated the first half batch of houses, the rest will be chosen by lottery. Some pensioners may have to wait for months. “I’m by myself, so I imagine I’ll be last in line,” frets Konno Tami (75), who has no children and lost her husband years ago. Even mothers face rationing. Mrs. Sasaki will be low on the list because her children are older, she predicts. “But everyone is suffering now so I understand.”

Schoolfriends Sasaki Maeka (15) and Murakami Urara (14) are recalling the day of the quake, when they were in this gymnasium, practicing for their junior high school graduation ceremony. “The roof began to shake and at first people were OK, but it got worse and we thought the roof would fall,” says Maeka. “When it stopped, the tsunami alert came. Some students started crying, saying their homes would be destroyed, their families gone. The worst thing was we couldn’t leave. But we didn’t cry. We were trying to be strong.”

Kanno Shingo, 27, from Iitate Village, is married with an 18-month old daughter called Reon. His wife and baby are staying with friends away from Iitate. The rest of the family is at Yonezawa evacuees centre. Kanno works as a farmer, mainly brocolli and tobacco during the summer, then he does construction work with TEPCO during the winter. He hasn’t been back to the plant since the quake, but has had several calls from his boss asking him if he will return to deal with radioactive waste.

We reached Shingo by tracing his uncle, Masao, to the Yonezawa centre. From there, we got the village hall in Iitate to summon him. Shingo and Masao’s son, Matsumi, have stayed on in Iitate. He’s remarkably relaxed about talking.

Asked what he thinks of the so-called Fukushima 50, the workers who remained behind to clean up the radioactive waste in the reactors, he says: “I’m sure they’re as afraid as me. It’s bravery but it’s also about money. Maybe they want to be paid more than they’re afraid of the radiation. Of course, some of them are brave, some of them want money, some of them are both.”

Asked if he was a samurai, he laughed and said, “I’m somewhere in between. My wife wouldn’t want me to be a samurai.”

“Farming may not have a future here so I may have to get a job somewhere else. I’d prefer to stay, but if there are no jobs . . .? I haven’t decided whether I’ll go, I know it’s dangerous. They are offering up to 20 times what we usually get.”

David McNeill writes for The Independent, The Irish Times and The Chronicle of Higher Education. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator.

Recommended citation: David McNeill, Communities Struggle to Rebuild Shattered Lives on Japan’s Coast, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 14 No 4, April 4, 2011.