This article is available in translation in Japanese, Korean, Chinese and Ukrainian.

Gavan McCormack

“Senkaku Islands Colonization Day”

In December 2010, the Okinawan city of Ishigaki (within which Japanese administrative law incorporates these islands) adopted a resolution to declare 14 January to be “Senkaku Islands Colonization Day.” The “Colonization Day” is intended to commemorate the incorporation of the islands by cabinet decision 116 years earlier. China immediately protested.

Ishigaki was following the model of the Shimane Prefectural Assembly, which in 2005 declared a “Takeshima Day” in commemoration of the Japanese state’s incorporation 100 years earlier of the islands known in Japan as Takeshima but in South Korea (which occupies and administers them) as Tokdo. That Shimane decision prompted fierce protests in South Korea. The Ishigaki decision seems likely to do no less in China. Why should these barren rocks, inhabited only by endangered short-tailed albatross, be of such importance to otherwise great powers? Whose islands are they? How should the contest over them be resolved?

The Incident

On the morning of 7 September 2010, the Chinese fishing trawler Minjinyu 5179 collided, twice, with Japanese Coastguard vessels in the vicinity of the islands known in Japan as the Senkaku and in China and Taiwan as Diaoyu or Diaoyutai.1 These islands are under effective Japanese control, but are claimed also by China and Taiwan. Zhan Qixiong, captain of the Chinese vessel, refused to obey the Japanese orders to withdraw. By Japanese accounts, he deliberately rammed his ship into the Coastguard vessels and was only later apprehended and sent to prosecutors for offence against Japanese law (interfering with officials conducting their duties).

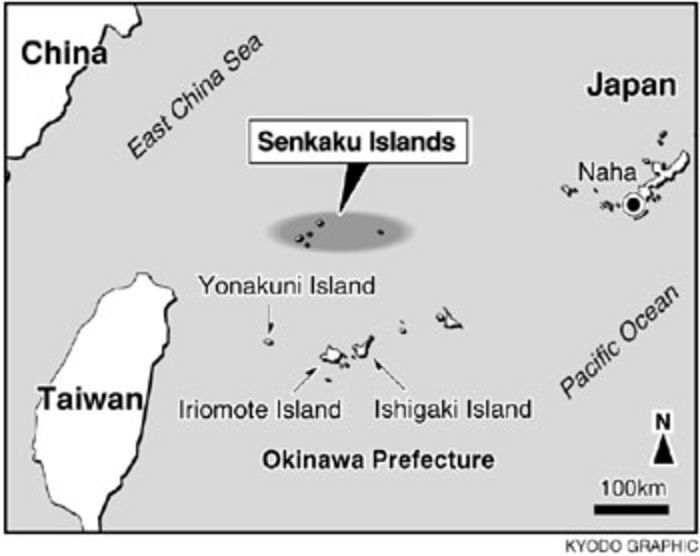

The island group is made up of 8 rocky, uninhabited outcrops, a sprinkling of poppy seeds on the East China Sea. The largest of them about 4 square kms, they are about equi-distant (less than 200 kms) to the coast of Taiwan and to the Japanese Okinawan islands of Yonaguni and Ishigaki, or a little over 400 kms from Okinawa’s main island. On the edge of the Chinese continental shelf, they are separated from Okinawa by the deep waters (over 2,000 metres) of the Okinawa Trough.

Following the seizure of the Chinese trawler and the arrest of captain Zhan, the Japanese government stated its position: there was “no room for doubt” that the islands were an integral part of Japanese territory: (wagakuni no koyu no ryodo), there was no territorial dispute or diplomatic issue, and captain Zhan was simply being investigated for breaches of Japanese law.

Yet plainly there was doubt. China (both the People’s Republic and the Republic, or Taiwan) disputes the Japanese claim to sovereignty.2 The US, which occupied the islands between 1945 and 1972, was carefully agnostic about their sovereignty when returning to Japan “administrative rights” over them, and it has reiterated that stance on many subsequent occasions.3 As re-stated in the context of the 2010 clash, the US position is that sovereignty is something to be settled between the claimant parties.4 Furthermore, while Japan has exercised “administrative rights” and thus effective control since 1972, it has blocked all activities on the islands, by its own or other nationals, thereby acting as if sovereignty was indeed contested. Thus, with two Chinese governments denying it, and the US refusing to endorse it, it is surely whistling in the wind for Japan to insist there is “no dispute” over ownership. Whoever initiated them, the clashes of that day raised a large question-mark over the islands.

As news of the clash exploded into the media of the region, the Japanese ambassador to China was summoned to hear China’s protests, demonstrations spread quickly in both Chinese and Japanese cities, diplomatic contacts were suspended, rare earth exports from China stopped, concerts and student exchange visits involving many thousands of both Chinese and Japanese young people cancelled. Defence planners on all sides dusted off plans for achieving, and if necessary demonstrating, military superiority.

Responding to Japanese claims that there was “no dispute” and that procedures against the Chinese Captain would proceed with due seriousness and deliberation (shukushuku) under Japanese law, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, in New York on 21 September, declared, “When it comes to sovereignty, national unity and territorial integrity, China will not yield or compromise.”

The formal Japanese position – that there was no dispute – rang hollow from the outset. Japan handled the crisis in a characteristic and revealing way, by seeking first of all to escalate it from a bilateral dispute over borders to a security matter involving the United States. Following a meeting on 23 September, Foreign Minister Maehara declared that US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had given him the assurance that the Senkakus were “subject to Article 5 of the US-Japan Security Treaty,” the clause of the treaty that authorizes the US to protect Japan in the case of an armed attack “in territories under the administration of Japan.”5

What Clinton actually said, however, is not clear. Only weeks earlier, the US had communicated its reluctance to back Japan’s Senkaku claims.6 Not only did the State Department account of the September meeting not mention the pledge claimed by Maehara but its spokesman repeated the formal US government position urging the two countries to resolve the dispute and stated, “We don’t take a position on the sovereignty of the Senkakus.”7 Despite Maehara’s claim, it seemed more likely, as Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times put it on 10 September, that there was “zero chance the US would activate Ampo [the security treaty] over such an issue.” Weeks later, however, at a joint press conference in Honolulu with Foreign Minister Maehara, Clinton did specifically affirm the applicability of Article 5 to the Senkakus.8 It means that the US re-thought and reversed its position in the space of just over a month, evidently under keen Japanese pressure, committing itself to the possible use of force, i.e., war, in defence of islands on whose legal ownership it took no position.9

However, despite extracting the ambiguous US backing, the Japanese determination to subject Captain Zhan to the full weight of the Japanese law quickly crumbled. On 25 September, following an “autonomous decision of local prosecutors” that was almost universally assumed actually to have been made at the highest levels of government in Tokyo, Zhan was released and returned home. China’s Foreign Ministry demanded an apology and compensation, and Japan’s Foreign Ministry counter-claimed for damage caused to its vessels by the collision. The doyen of Japan’s liberal media, the Asahi’s editor-in-chief (and former Beijing correspondent) Funabashi Yoichi, lamented that while Japan had been “clumsy,” China was to be blamed for its “diplomatic shock and awe” campaign that had brought the two giant neighbour countries to “ground zero, [so that] the landscape is a bleak, vast nothingness.”10 Though Funabashi couched his message in the measured tones of the liberal intellectual seeking China’s understanding, Japanese resentment at China’s dramatic economic growth and increased international standing was palpable.

It was widely reported in Japan that the “international community” supported Japan’s position. Although levels of international support are irrelevant to the merits of the case, there is little doubt that, in East and Southeast Asia, anxiety about China’s dramatic rise fed into support for the reassertion of US alliance-based “containment.” As the Sydney Morning Herald’s China correspondent wrote, “One by one, China’s neighbours are welcoming the reassertion of US power to balance that of China.”11 Other media too rallied to the Japanese cause, or more broadly to the anti-China cause. Weeks after the incident, the New York Times quoted with approval the view of China as “increasingly narrow-minded, self-interested, truculent, hyper-nationalist,”12 and adjectives such as “truculent,” and “arrogant” began to attach almost as a matter of course to “China” in mainstream Western media. The Cold War was back.

However, when Defence Minister Kitazawa Toshimi toured regional capitals in an attempt to drum up diplomatic support, he apparently failed to find a single Defence Minister ready to offer it.13 When Foreign Minister Maehara filed a complaint against Google, demanding it remove the Chinese names from its maps of the islands, not only did Google refuse but the attempt to censor the international media made Japan look both desperate and, in a sense, “Chinese” in its heavy-handed bid to intimidate.14 Furthermore, Japan’s “humiliating retreat” (as the New York Times put it on 25 September) by its sudden release of the Chinese captain signalled to the region that it was actually lacking in the sovereignty it so loudly declared.15

Despite the resolution of the immediate crisis by Captain Zhan’s release, nationalistic passions and fears, once stirred, were not easily settled. Demonstrations in both countries continued. The tabloid daily Fuji in Tokyo (1 October) denounced what it called Japan’s “appeasement (dogeza) diplomacy and widely syndicated pundits thundered that “If Japan gives in on the Senkakus, China will come and grab Okinawa next” (Sakurai Yoshiko) or that “What China’s doing is no different from gangsters. If Japan does nothing, it will suffer the same fate as Tibet” (Tokyo Governor, Ishihara Shintaro).16 Tamogami Toshio, former Chief of Staff of the Air Self-Defence Forces and now president of the “Ganbare Nippon! [Go for it Japan!] All-Japan Action Committee” also stressed the “threat” to Okinawa: “China is clearly aiming to annex Okinawa. So we need to put a stop to it.”17

Such views were by no means confined to the right. Apart from the liberal Asahi referred to above, in general the left-right political divide in Japan dissolved into an “all Japan” media front on this issue. A broad national media consensus supported the Japanese official story of its Senkaku rights, protested China’s threat to Japan’s sovereign territory and insisted on the importance of the security alliance with the US in order to cope with China’s challenge. Japan’s leading financial daily declared that Japan had to cooperate with the United States and Europe in putting pressure on China to become a “responsible,” “civilized” country.18 When the chairman of the Japanese Communist Party joined the chorus declaring the islands to be Japan’s sovereign territory that must be defended, the Chief Cabinet Secretary and the heads of both present and past ruling parties (the DPJ and the LDP) congratulated him.19 The widely syndicated Sato Masaru lamented the blows Japan’s “national interest” had suffered because of amateurish diplomacy and called for a firm Japanese response in kind, “as an imperialist country” to “China’s imperialism.”20

Sato’s role merits attention because of his unique stance as a former Ministry of Foreign Affairs researcher and self-proclaimed rightist embraced also by the “liberal” media and intelligentsia. As of 2010, he was the most prominent advocate of the Okinawan anti-base cause in mainland Japan, with regular columns in Sekai and in Shukan kinyobi (which even published a special issue under his editorship on 12 November 2010), as well as a long running monthly column in the Okinawan daily Ryukyu shimpo.21 Yet Sato’s agenda of opposition to any new Marine base in Okinawa did not fit well with his insistence on confronting China as one imperialist power to another. With his bottom line, as I have argued elsewhere,22 being reinforcement of the Japanese national interest, the Henoko anti-base struggle was for him essentially a means to that end. Enhanced US-Japan military cooperation was not objectionable per se but the way Tokyo was proceeding to foist the new base on Okinawa, by discrimination, was. For Japan to adopt, as he urged, a resolutely “imperialist” stance in opposing China required that it reinforce military positions (whether US or Japanese, or some combination) in Okinawa, especially in the Okinawan islands closest to China.

The Okinawan vulnerability to such “national interest” logic in the wake of the September incident became apparent as prominent Okinawan figures, including Ginowan mayor and candidate for Okinawan Governor, Iha Yoichi, and distinguished author and Okinawan spokesman Medoruma Shun, adopted its frame.23 It became possible to imagine that Senkaku/Diaoyu might even serve as the axis of Okinawan conversion to greater understanding of the national government’s defence and security agenda. The abandonment of the Henoko project might be tolerable to the defence bureaucracy in Tokyo and Washington if it was combined with readiness to reinforce US-Japanese military presence and containment of China. To the extent that “China threat” perceptions spread, Okinawa’s anti-base movement would surely weaken.24 Hatoyama’s 2009 project to turn the East China Sea into a “Sea of Fraternity” looked in 2010 more likely to degenerate into a DPJ project for building confrontation and tension.

As the justice or legality of Japan’s claims went unchallenged and, for the first time in the post-1945 era anti-China sentiment began to spread at the mass level, the political dividing lines between left and right were swallowed by a wave of chauvinism. Blaming Captain Zhan (and the government of China) for reducing the bilateral relationship to the devastation of “ground zero,” Japanese elites lost the capacity to appreciate the Chinese position or to achieve a self-critical awareness of their own.

The History

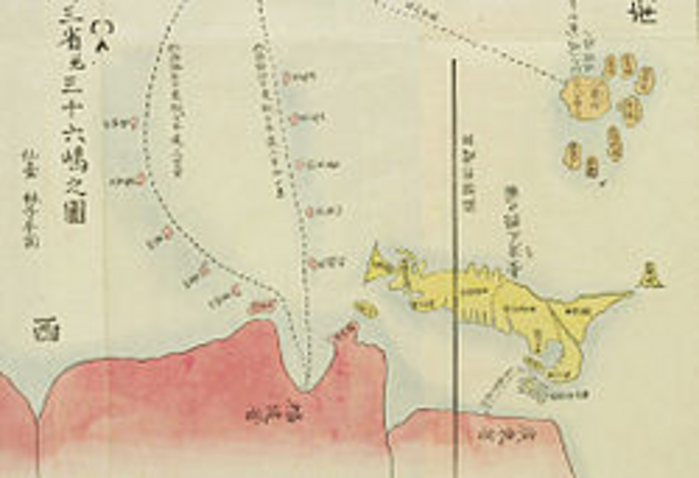

From the 14th century, Chinese documents record and name the islands as important reference points on the ancient maritime trading route between coastal China (Foochow) and Okinawa.25 The designated route for tribute missions between the Ryukyu kingdom and the Chinese court during the Ming and Qing dynasties lay via these small islands. The Japanese geographer, Hayashi Shihei, follows the Chinese convention, including the islands, with their Chinese names, as Chinese territory, in his 1785 map.

|

Hayashi Shihei’s map from his Sangoku tsuran zusetsu (General outline of three countries), 178526 |

The near universal conviction in Japan with which the islands today are declared an “integral part of Japan’s territory” is remarkable for its disingenuousness. These are islands unknown in Japan till the late 19th century (when they were identified from British naval references), not declared Japanese till 1895, not named till 1900, and that name not revealed publicly until 1950.27

The determination in 2010 not to yield one inch on the Senkaku issue may have owed something to the nagging fear that China’s claim, if admitted on Senkaku, might quickly extend to Okinawa. Japan’s claim to the Senkakus followed shortly after it had established its claim over Okinawa by detaching the Ryukyu kingdom, tied to the court in Beijing by a four century-long “tribute” relationship, from its place in the tribute order. The despatch of a Japanese naval expedition to Taiwan in 1874 to “protest” the killing of Ryukyuan (Miyako Island) fishermen, passing without effective protest from China, was taken by Japanese leaders to signal for international law purposes that China acquiesced in Japan’s claims. It was followed, in 1879, by extinction of the kingdom and Okinawa’s incorporation as a Japanese prefecture. The years of the rise of the modern Japanese state were the years of crisis and decline for the Chinese imperial state, when the country was subject to imperialist encroachment, catastrophic wars and internal rebellions. The revolutionary modern Japanese state, founded in 1868, exploited China’s weakness and its multifaceted crises to join the ranks of imperialists, expanding at imperial China’s cost, by wresting from it first the Ryukyu Islands, then Taiwan and the Senkakus, then Northeast China, till eventually it plunged the region into full-scale war.

On the largest island of the Senkaku group, a Japanese businessman began to make a living from 1884, collecting albatross feathers and tortoise shells.28 However, his requests to the government in Tokyo for a formal leasehold grant of the territory were refused for over a decade until war between Japan and China from 1894, and the series of Japanese victories that defined it, persuaded the Japanese cabinet in January 1895 to declare them Japanese territory, part of Yaeyama County, Okinawa prefecture. The Japanese claim rested on the doctrine of terra nullius – the presumption that the islands were uninhabited and not claimed or controlled by any other country. However, it stretches common sense to see the absence of Chinese protest or counter-claim as decisive under the circumstance of war, the more so as the appropriation of the Senkakus was followed just three months later by the acquisition of Taiwan, under the Treaty of Shimonoseki.

Nearly 40 years have passed since Kyoto University’s Inoue Kiyoshi reached his conclusion that, “Even though the [Senkaku] islands were not wrested from China under a treaty, they were grabbed from it by stealth, without treaty or negotiations, taking advantage of victory in war.”29 It is a view that today appears to have little support among Japanese scholars who, in general, unite in declaring the appropriation of the islands legitimate and in accord with international law, dismissing as irrelevant the circumstances under which Japan made its claim and (with few exceptions) expressing outrage that China has not accepted their reading of law or history.30

From 1895 to 1945, that is to say from the first to the second Japan-China war, China was in no position to contest Japan’s claims. A Japanese community of several hundred people settled on the Senkaku group, where, inter alia, they ran a dried bonito (katsuobushi) factory, and that settlement continued for almost a half-century till 1942. After its defeat in the Asia-Pacific War, Japan was obliged by the Potsdam Declaration to surrender all territories seized through war, but it insisted then, and has continued to insist ever since, that the Senkakus were part of Okinawa (and therefore not a spoil of war).The difficulty with this is that they plainly were not part of Ryukyu’s “36 islands” in pre-modern times nor when the prefecture was established in 1879, being only tacked on to it 16 years later.

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, the US military took effective control of Okinawa and the Senkakus, and international attention only focussed again on the islands from 1968, when a UN (ECAFE) survey mission reported likely oil and gas reserves in their adjacent waters,31 and 1969, when the US agreed to return sovereignty over Okinawa to Japan. For the nearby Senkaku island group, it was careful to stress that what was being transferred to Japan were “administrative rights,” not sovereignty.32

As Kimie Hara of Canada’s Waterloo University points out, the US played a significant role in the creation and manipulation of the “Senkaku problem”: first in 1951 and then again in 1972. Under the 1951 San Francisco Treaty post-war settlement, it planted the seeds of multiple territorial disputes between Japan and its neighbours: Japan and 90 percent communist China over Okinawa/Senkaku, Japan and 100 percent communist USSR over the “Northern territories,” Japan and 50 percent communist Korea over the island of Takeshima (Korean: Tokdo). These disputed territories served “as ‘wedges’ securing Japan in the Western bloc, or ‘walls’ dividing it from the communist sphere of influence.”33 Again in 1972 by leaving unresolved the question of ownership of the Senkaku islands when returning Okinawa to Japanese administration, US Cold War planners anticipated that the Senkakus would function as a “wedge of containment” of China. They understood that a “territorial dispute between Japan and China, especially over islands near Okinawa, would render the US military presence in Okinawa more acceptable to Japan.”34 The events of 2010 proved them far-sighted.

On the eve of the reversion of Okinawa (the Senkakus included) to Japanese administration, both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China laid counter-claims. Dispute flared, only cooling when, in 1978, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping made his circuit-breaking offer:35

“It does not matter if this question is shelved for some time, say ten years. Our generation is not wise enough to find a common language on this question. Our next generation will certainly be wiser. They will surely find a solution acceptable to all.”36

Despite occasional lapses, and a steady increase in the number of Chinese fishing boats taking from the waters around the islands (up to 400 per year), that “gentleman’s agreement” held until September 2010, when Japan apparently repudiated it by arresting the Chinese captain, insisting there was no dispute and refusing to listen to China’s protests.

The Consequences

There is no question but that the Japanese government lost face by “giving in” to Chinese pressure and releasing Captain Zhan. But the incident also helped boost important agendas, notably concerning Japan’s relationship with the US, the Okinawa “base relocation” problem, and future military posture.

By attaching priority to extracting an American promise to “protect” the Senkakus, Prime Minister Kan Naoto’s government showed its determination to continue Japan’s “Client State” status.37 The initiatives of Kan’s predecessor, Hatoyama Yukio, for closer Japan-China cooperation in the formation of an East Asian Community, became a thing of the past. Instead, Kan used the events to precipitate closer integration of Japanese and US military planning and operations in the Western Pacific and East Asia, and to cooperate in grand regional war games that were plainly intended to intimidate China.

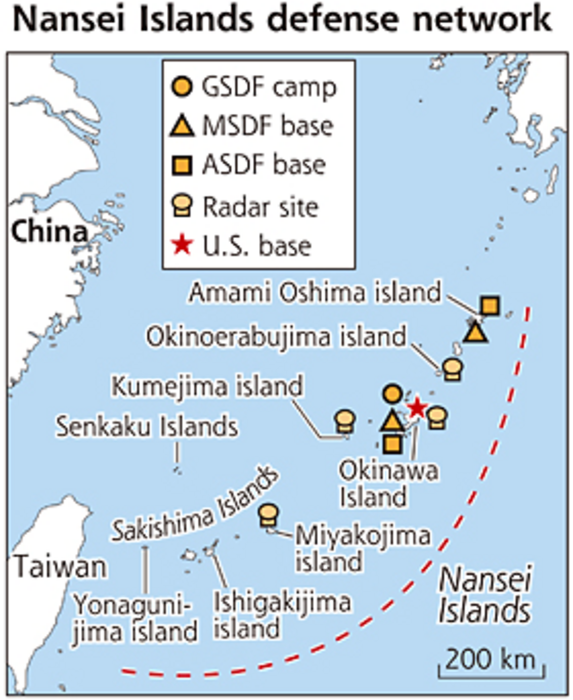

Adding “China threat” to the existing “North Korea threat” helped advance a security agenda under Kan’s DPJ that had been unthinkable under its Liberal-Democratic party predecessors, though the latter were widely assumed to have been far more hawkish. On 27 August, just weeks before the clashes at sea, Prime Minister Kan accepted the report of his special committee on security in the new era (Shin Ampo kon),38 and new National Defence Program Guidelines were adopted by the Cabinet on 17 December 2010.39 Under the Guidelines, to cover the decade commencing in 2011, Japan was to substitute a “dynamic defence force” for the existing “basic defence force” concept, enhance existing security links with the US, and substantially reinforce Self Defence Force presence in the outlying islands in the East China sea. Plans were reportedly underway to beef up the current level of SDF presence in Okinawa from 2,100 to 20,000, with the first contingent, 200-strong, to be sent in the near future to Yonaguni and close attention paid also to the islands of Miyako and Ishigaki.40 Military critic Maeda Tetsuo read the plan as the agenda of a renascent military great power, freed of the restraints of the constitution’s “peace” clause (Article 9), which would, in effect, be revised or cancelled,41 and as a contradiction of the Democratic Party’s own defence principles. He wrote:

“These hawkish new Defence Guidelines appear to contradict the DPJ’s own basic stance. The substitution of “dynamic defence force” for “basic defence force” means in effect abandonment of exclusive defence and transformation (of the defence forces) to a “fighting SDF.”42

|

Yomiuri shimbun, 11 November 2010 |

For Okinawa, the Senkaku incident and the Kan government’s military build-up program (in the context of worsening confrontation with China) held especially serious implications. A glance at the map is sufficient to show that access from the heartland of China to the Pacific Ocean requires passage of channels through the Nansei islands between Kyushu and Taiwan. The international waters of the Miyako Strait (between Okinawa Island and Miyako Island) are crucial to China’s Pacific Ocean access, and in March and April 2010, several large Chinese naval flotillas passed through them.43

Even before the Senkaku clash, the Kan government had brushed aside evidence of near total opposition from within the prefecture and declared its determination to build in Northern Okinawa a new base for the US Marine Corps whose major role would clearly be to “deter” China (and North Korea). After the September events, the Kan government only hardened its stance. By involving Okinawa in the nation-wide mood of fear and hostility to China post-September 2010, Tokyo might well reasonably expect that opposition to the Marine base project would weaken. The Kan government and defence and foreign affairs officials in Tokyo must have taken heart when the Okinawan Prefectural Assembly and the City Assemblies of Miyako and Ishigaki (geographically closest to Senkaku, which administratively forms part of Ishigaki City) adopted unanimous resolutions affirming that the islands did indeed “belong to Japan” and calling for Japan to be resolute (kizentaru) in defending them,44 and when prominent “anti-base” figures either supported or else demanded Tokyo take a stronger stance in defence of the Japanese position. The victory in the Okinawan prefectural gubernatorial election (28 November) of incumbent Nakaima Hirokazu might also be seen as favourable to Kan’s base construction agenda. Even though Nakaima had committed himself to demanding no new base be built in Okinawa, he had made that shift only with palpable reluctance, without specifically renouncing his earlier readiness to allow the base to be constructed provided only it be moved a short distance, say 100 metres or so, offshore.

Despite the evidence of a convergence of Okinawan and mainland thinking in insistence on Japanese sovereignty over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and blaming China for the clash, there were nevertheless significant differences. First, Okinawans had learned from their experience of 1945 that armies do not defend people, and so tended to believe that any defence of the Senkakus that rested on militarizing them and embedding them in hostile confrontation between Japan and China would expose Okinawa to greater threat rather than improve its security.45 It is also the case, as defeated gubernatorial candidate Iha pointed out, that Okinawans have a long historical memory of friendly relations with China, and in contrast to mainland fears and anxieties, many Okinawans rather feel “close” to it.46 Second, for Okinawans, the Senkaku issue is not so much one of national security as of livelihood. It is the fishing grounds around the islands that are precious, rather than national security considerations or seabed oil and gas reserves.47 As Okinawa International University’s Sato Manabu put it, “It is obvious that Okinawa has to find a future as an “open” border land. Okinawa has to make every effort to build stronger ties with neighbouring nations, otherwise we will be cornered.”48

The Prospect

Japanese scholar Wada Haruki insists it is “idiotic” for Japan and China both to insist on exclusive (koyu) territorial rights to uninhabited rocks.49 Though uninhabited, however, the islands hold considerable strategic and probably also economic significance, the former because of their location at the heart of the Northeast Asia region, and the latter because of the accompanying exclusive economic rights to the resources of hundreds of square kilometres of the East China Sea. Confrontation, progressively militarized and in a “zero-sum” approach to territorial and resource matters, would be a recipe for disaster for both and both are surely well aware of the risks of allowing that to happen.

It was too easy in Japan to dismiss anti-Japanese sentiment and demonstrations in China as a device by an authoritarian regime to divert attention from itself, and thus to turn a blind eye to the grievances and suspicions widely felt there. The way that anti-China passions swept Japan following the September clashes would only confirm the worst of those Chinese fears and suspicions.

While the Japanese media united in projecting a picture of China as threatening and “other,” it paid minimal attention either to the circumstances surrounding the Japanese claim to the islands or to the reasons for the recrudescence of suspicion of Japan in China. It took it for granted that Japan “owned” the islands, concentrating its attention only on whether or not captain Zhan had deliberately rammed the Coastguard vessels and who might have leaked the apparent film footage of the events that transpired. Few expressed any hesitation over Japan’s trashing the Deng “freeze” agreement that was the basis for China-Japan accommodation, or over the contempt with which the government met China’s claims by denying they existed. Nor was there sign of dissent when respected opinion leaders accused China of truculence or diplomatic “shock and awe.” Virtually nowhere were there to be found discussions of the possible “blowback” aspect of the events, i.e., that they might simply have brought to the surface unassuaged Chinese suspicions over Japan’s long neglected or insufficiently resolved war responsibility, the high-level denials of Nanjing, the periodic right-wing attempts to sanitize history texts, the refusal to accept formal legal responsibility for the victims of the Asia-wide “Comfort Women” slavery system and the wartime forced labor issue, and the periodic visits by Prime Ministers (notably Koizumi, 2001-2006) to Yasukuni. Zhou Enlai is said to have remarked when deciding that China would not seek war reparations from Japan, “We will strive to forget, but you, please do not forget.” Japan should not forget.

The most detailed study in English of the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue, published just a decade ago, concluded that here were only four possible ways in which it might be resolved: by Sino-Japanese agreement, unilateral Japanese action, war, and referral to the International Court of Justice.50 Of these, he insisted, the first was the only “realistic” way forward. Blocking it for nearly three decades has been Japanese intransigence and insistence on exclusive “effective control.” Under the Kan government, Japan has moved away from the Hatoyama vision of cooperation in the construction of an “East Asian Community”, but the antagonistic approach to questions of territory, resources, and environment can hardly offer any way forward.

Peace and security in East Asia depend on the governments and peoples of the region taking the initiative to remove the “wedges of containment” that US planners left ambiguously and threateningly embedded in the state system they designed more than half a century ago.

|

Bridge of Nations Bell (1458) (Okinawa Prefectural Museum, Replica in Shuri Castle) |

For Okinawa the Senkaku/Diaoyu events serve as a message to think again about the history of the islands’ links with (mainland) Japan, China and Korea. Once the flourishing independent kingdom of Ryukyu, whose aspiration was to serve as the bridge linking the neighbouring states and peoples, Okinawa was subjected twice to forceful appropriation by mainland Japan, first in 1609 and then, decisively, in 1879 when its long and friendly links with China were finally severed. Modern history did not deal kindly with Okinawa, and today, as waves of chauvinism and militarism again wash on its shores, only by returning to the vision of the islands as uniquely close to China, Korea and mainland Japan (as written on the great “World Bridging” Bankoku shinryo bell, cast in the year 1458 and now on display in the prefectural museum), can it hope to calm and survive the gathering storms.51

Gavan McCormack is emeritus professor of Australian National University, an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator, and author, most recently, of Client State: Japan in the American Embrace (New York, 2007, Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing 2008). He has written extensively on this site on matters to do with Okinawa and the US-Japan relationship. He delivered the Japanese version of this paper to the Okinawa Forum, jointly sponsored and convened by Japan Focus and Okinawa University at Okinawa University in December 2010.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, Small Islands – Big Problem: Senkaku/Diaoyu and the Weight of History and Geography in China-Japan Relations, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 1 No 1, January 3, 2011.

Articles on related subjects:

•Wada Haruki, From the Firing at Yeonpyeong Island to a Comprehensive Solution to the Problems of Division and War in Korea

•Tim Beal, Korean Brinkmanship, American Provocation, and the Road to War: the manufacturing of a crisis

•Nan Kim and John McGlynn, West Sea Crisis in Korea

*Wada Haruki, Resolving the China-Japan Conflict Over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands

*Peter Lee, High Stakes Gamble as Japan, China and the U.S. Spar in the East and South China Sea

*Tanaka Sakai, Rekindling China-Japan Conflict: The Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands Clash

Notes

1 References in the following text to “Senkaku” carry no implication as to sovereignty or “proper” name.

2 The question of Taiwan deserves full treatment but is passed over in this short essay save to note that while the majority (and current government) in Taiwan persist in claiming sovereignty a minority concedes it to Japan, and that, when a collision between a Taiwanese ship, the “Lian-ho,” and a Japanese coastguard vessel led to the sinking of the former in June 2008, the then mayor of Taipei, as of 2010 president of Taiwan, Ma Ying-jeou, spoke of war as a last resort for defence of national sovereignty and Japan apologized and paid compensation.

3 Kimie Hara, Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific, New York and London, Routledge, 2007, especially chapter 7 “The Ryukyus: Okinawa and the Senkaku/Diaoyu disputes.”

4 See Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “The Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands,” (accessed 17 December 2010); also “Senkaku islands Dispute, ” Wikipedia (17 November 2010)

5 “Clinton: Senkakus subject to security pact,” Japan Times, 25 September 2010.

6 “US fudges Senkaku security pact status,” Japan Times, 17 August 2010.

7 Ibid. For details, Peter Lee, “High Stakes Gamble as Japan, China and the U.S. Spar in the East and South China Seas,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 43-1-10, 25 October, 2010.

8 “Joint Press availability,” Department of State, 27 October 2010, Link.

9 It is even possible that Tokyo might have orchestrated the incident at sea in order “to force an unenthusiastic Obama administration to side with Japan on the Senkakus.” (Peter Lee, cit.)

10 Funabashi Yoichi, “Japan-China relations stand at ground zero,” Asahi shimbun, 9 October 2010, reproduced at East Asia Forum, 20 October, 2010.

11 John Garnaut, “China detonates regional goodwill,” Sydney Morning Herald, 23-24 October 2010.

12 “Taking harder stance toward China, Obama lines up allies,” New York Times, 25 October 2010.

13 Visiting Vietnam, Indonesia, Australia, Thailand, and Singapore, (Mo Ban fu, “Nitchu shototsu no yoha wo kakudai sasete wa naranai,” Sekai, December 2010, pp. 116-123.)

14 “Senkaku Islands dispute,” Wikipedia, cit.

15 Suggesting such a view: Nakano Seigo, “Dato datta chiken handan,” Okinawa Times, 4 October 2010.

16 Sakurai in Shukan posuto, 8 October 2010, and Ishihara in Shukan bunshun, 7 October 2010, quoted in Mark Schreiber, “Weeklies, tabloids hawkish over China,” Japan Times, 10 October 2010.

17 Quoted in Yuka Hayashi, “China row fuels Japan’s right,” Wall Street Journal, 29 September 2010.

18 “Bei-O to kyocho shi Chugoku o sekinin taikoku ni michibiite,” Nihon keizai shimbun, 1 October 2010.

19 “Senkaku mondai – Nihon no ryoyu wa rekishiteki, kokusaihoteki ni seito,” Akahata, 5 October 2010, and on the congratulations, Akahata, 10 October 2010.

20 Sato Masaru, “Chugoku teikokushugi ni taiko suru ni wa,” Chuo Koron, November 2010, pp. 70-81. In similar vein, Sato called (“Honne koramu,” Tokyo shimbun, 26 November 2010) for Japan to respond to China force with force, making clear its intent to drop the Cabinet Legal Bureau’s interpretation of the constitution so as to be able to join the US in collective security missions, thereby deepening the alliance with the US.

21 For my general reflections on Sato Masaru: “Ideas, Identity and Ideology in Contemporary Japan: The Sato Masaru Phenomenon,” 1 November 2010.

22 Ibid.

23 Neither Medoruma nor Iha appear to doubt the historical legitimacy of Japan’s Senkaku possession. For Iha, Senkaku is “indisputably a part of Okinawa,” and Chinese authorities needed to deal with Chinese fishermen and control anti-Japanese demonstrations (interview with Iwakuni Yasumi, 25 September 2010). For Medoruma too, China was to blame for the September clash, and the Japanese government to be criticized only for its “weak-kneed” response. (“Chugoku gyosen no sencho shakuho ni tsuite,” Uminari no shima kara, 25 September 2010, link) For fuller discussion, see Media debugger, “Senkaku=Chogyoto o meguru shogensetsu hihan (4) Shinryakukoku no ‘kokumin no seishi’ o ninau ‘oru-Japan’ gensho,” 4 November 2010.

24 Kim Sonho, “Chugoku kyoiron fusshoku o,” Okinawa Taimusu. 1 October 2010.

25 For brief histories of the islands and analyses of their disputed status, see Inoue Kiyoshi, Senkaku retto – Chogyo shoto no shiteki kaimei, Tokyo, Gendai hyoronsha, 1972; “Senkaku Islands dispute,” Wikipedia, cit; Wada Haruki, “Resolving the China-Japan conflict over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 43-3-10, 25 October 2010; Taira Koji, “The China-Japan clash over the Senkaku islands,” Japan Focus, n.d. (2006 ?), and Tanaka Sakai, “Rekindling China-Japan Conflict: The Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands Clash,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 39-3-10, 27 September 2010.

26 Reproduced in Wikipedia, “The Senkaku islands dispute”.

27 Unryu Suganuma, Sovereign rights and territorial space in Sino-Japanese Relations: Irredentism and the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2000, pp. 88-9. See also the home page of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Senkaku shoto no ryoyuken ni tsuite no kihon kenkai,” link.

28 Inoue, pp. 103ff.

29 Inoue, p. 123.

30 The exception is Tokyo Metropolitan University’s Murata Tadayoshi. See Murata, Senkaku retto/chogyoto mondai o do miru ka, Rinjin shinsho, 07, 2006. In the blogosphere, however, such anti-mainstream views are expressed and what might be described as the “Inoue Kiyoshi line” is affirmed. See, for example, Heito supichi ni hantai suru kai, “Daioyutai/Senkaku o meguru Nihon no kunigurumi no haigaishugi ni kogi shimasu,” 10 October 2010 (link), and Media debugger, “Senkaku-Diaoyu to o meguru sho gensetsu hihan,” (link).

31 “…the shallow sea floor between Japan and Taiwan might contain one of the most prolific oil and gas reservoirs in the world, possibly comparing favourably with the Persian Gulf area.” United Nations Economic and Social Council, Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, Kabul, 1970, UN Doc.E/CN.11/L.239 (cited Suganuma, p. 129).

32 For the documents covering this: Suganuma, pp. 135ff; Urano Tatsuo et al, Chogyotai gunto (Senkaku shoto) mondai –kenkyu shiryo kihen, Tosui shobo, 2001, pp. 250-2.

33 Kimie Hara, Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific, 2007, p. 188.

34 Kimie Hara, “The post-war Japanese peace treaties and China’s ocean frontier problems,” American Journal of Chinese Studies, vol. 11, No. 1, April 2004, pp. 1-24, at p.23.

35 For this author’s reflections on the problem as of that time, see Jon Halliday and Gavan McCormack, Japanese Imperialism Today, London, Penguin, 1973, pp. 62-65.

36 Beijing Review, 3 November 1978 (cited in Suganuma, p. 138.)

37 For further discussion, see my Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, London and New York, 2007, Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing, 2008.

38 Arata na jidai no anzen hosho to boeiryoku ni kansuru kondankai, “Árata na jidai ni okeru Nihon no anzen hosho to boeiryoku no shorai koso – ‘heiwa sozo kokka’ o mezashite,” (link) August 2010.

39 Ministry of Defence, “National Defence Program Guidelines, FY 2011” (accessed 17 December 2010.

40 “China threat prompts plan for new GSDF unit,” The Yomiuri Shimbun, 11 November 2010, link.

41 Maeda Tetsuo, “Minshuto wa senshin boei o homuru na ka,” Sekai, November 2010, pp. 113-120.

42 Maeda Tetsuo, “Arasou jieitai ni henbo,” Ryukyu shimpo, 18 December 2010.

43 “Chinese navy’s new strategy in action,” International Institute of Strategic Studies, May 2010, link.

44 Takimoto Takumi, “Beigun kichi no kyoka to Senkaku wa kanren shinai,” Shukan kinyobi, 8 October 2010, p. 19. See also Masami Ito, “Maehara again defends holding Chinese skipper,” Japan Times, 29 September 2010.

45 As argued by Okinawa University’s Wakabayashi Chiyo, “’Kokka’ koeru hasso de,” Okinawa Taimusu, 2 October 2010.

46 Iha Yoichi, interview, Yomiuri shimbun, 23 October 2010. Iha’s position nevertheless was implicitly contradictory since, as noted above, he insisted on Japanese sovereignty over Senkaku.

47 Itoman Seiken, “Senkaku wa gyogyosha no meiko,” Okinawa Taimusu, 19 October 2010.

48 Sato Manabu, personal communication, 10 October 2010.

49 Wada, cit.

50 Suganuma, pp. 159-162.

51 Here I follow the sentiments of the Okinawa taimusu editorialist (26 October) in “Nitchu to Okinawa – daiwa koso kankei kaizen no michi.” The inscription on the bell reads, inter alia, “The Ryukyus are paradisiacal islands perfectly positioned in the South Seas which have adapted Korea’s outstanding culture, are inseparably linked to China, and enjoy intimate relationship with Japan…”