Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi, Translated by Richard H. Minear

Click here for Japanese original.

See below for video of Barefoot Gen

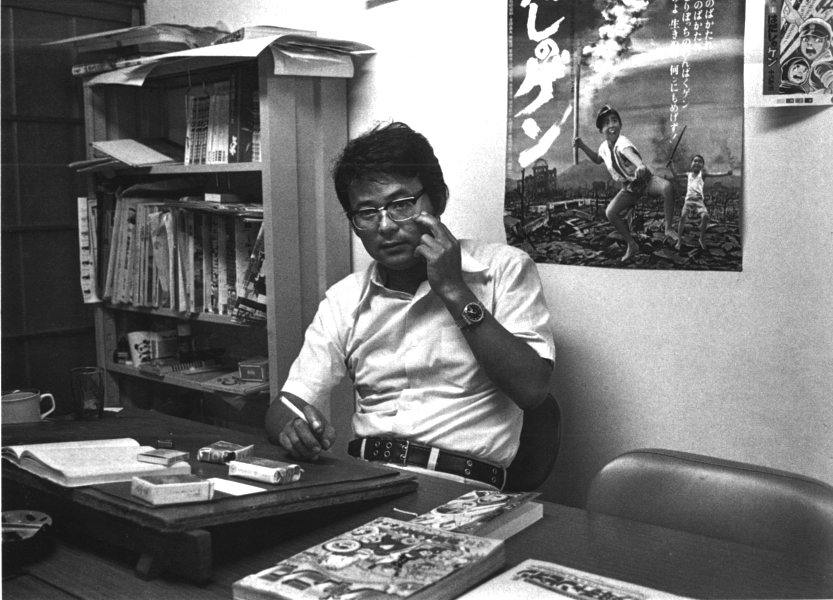

In August 2007 I asked Nakazawa Keiji, manga artist and author of Barefoot Gen, for an interview. Nakazawa was a first grader when on August 6, 1945 he experienced the atomic bombing. In 1968 he published his first work on the atomic bombing—Struck by Black Rain [Kuroi ame ni utarete]—and since then, he has appealed to the public with many works on the atomic bombing. His masterpiece is Barefoot Gen, in which Gen is a stand-in for Nakazawa himself. His works from Barefoot Gen on convey much bitter anger and sharp criticism toward a postwar Japanese politics that has never sought to affix responsibility on those who carried out the dropping of the atomic bomb and the aggressive war (the U.S. that dropped the atomic bomb, and the emperor and Japan’s wartime leaders who prosecuted the reckless war that incurred the dropping of the atomic bomb).

A Father’s Influence

Asai: Would you speak about your father’s strong influence on the formation of your own thinking?

Nakazawa: Dad’s influence on the formation of my thinking was strong. Time and again he’d grab me —I was still in first grade—and say, “This war is wrong” or “Japan’s absolutely going to lose; what condition will Japan be in when you’re older? The time will surely come when you’ll be able to eat your fill of white rice and soba.” At a time when we had only locusts and sweet potato vines to eat, we couldn’t imagine that we’d ever see such a wonderful time. But Dad said, “Japan will surely lose. And after the defeat, there’ll come a wonderful time.” At mealtimes he’d make all of us children sit up straight and listen to him—so much so that we grew sick of his voice. But we couldn’t believe that the time would ever come when we’d “be able to eat our fill of white rice.” Still, I think Dad really did see that far ahead. In fact, Japan did lose, and today’s an age of gluttony.

During Dad’s visits to Kyoto, he talked, I think, with a leftwing theater group. In his youth he had gone to Kyoto and studied Japanese-style painting of the Maruyama Okyo school and lacquerwork. He was always going to Kyoto, he belonged to Takizawa Osamu’s new theater, and he appeared on stage. He performed at Doctors’ Hall in Hiroshima’s Shintenchi, and he appeared in such things as Shimazaki Toson’s Before the Dawn [Yoakemae, 1929-1935] and Gorki’s The Lower Depths. The new theater was leftwing, so it was of course under surveillance by the authorities, and from what I hear, right across from the theater office the Thought Police kept an eye on everything—“Who went in?” One day they rounded everyone up.

That day I was really frightened. It was the most frightening thing my child’s mind ever encountered. I was about five. Her hair in disarray, Mom trembled, and seeing her, I thought something terrible had happened to our family. Dad had been taken away. I still can’t forget the fear I felt at that moment. The year was 1944.

Dad was taken away and didn’t come back. I asked Mom, “Why hasn’t Dad come home?” She lied to us. Told us he’d gone for his military physical. But it lasted too long. It was nearly a year before he returned. Later, when I asked members of the troupe, he was shoved into a detention center and hazed a good bit. He came back with teeth loose and broken. When they’re given food with salt, people can function; but given food without salt, they lose heart. I asked the members of the troupe and learned that that’s the food he was given, and he was tortured, too; he came home despondent. Even after he came home, he still told us what he had before: “This war is wrong.” Dad was a stubborn and headstrong man. Even under torture he never recanted. Dad’s younger brother stood surety for him, and he could come home. It was the end of 1944.

With Mom he built a new home in Funairi Honcho, and that’s where we lived.

Thumbnail sketch of his mother:

Mom was a dandy. One of her classmates was named Eda, and according to

Auntie, Mom wore pleated skirts, rode in cars, went to the movies, went to cafes—“Your mother lived a comfortable life in her youth.” But after coming as a bride to the house of an artist and having many children, she got angry when I drew pictures. Must have thought, I’ll never let him be an artist. She may have been fed up with Dad, who was an artist. Her family name was Miyake, and the Miyakes manufactured children’s bicycles. That such an affluent woman and my artist father married—there must have been some karma linking them. Perhaps their temperaments matched.

The Nakazawa family:

I was the third son, after two brothers and one sister. After me came a brother and an infant sister born on the day of the atomic bomb. On the day the atomic bomb was dropped, Mom was in her ninth month, her tummy large. Dad’s attitude toward the children was consistent throughout. My oldest brother did extremely well in school, and his teacher said, “Please let him continue his education.” Dad apparently got angry and was caustic: “A tradesman doesn’t need education.” Mom intervened, and Dad said, “Since you speak so highly of him, we’ll let him go,” and he entered Fourth Higher School. Mobilized out of school, he went to the naval armory at Kure and did welding. Worked on a section of Battleship Yamato. He prided himself on actually having inserted his entire body into the Yamato’s artillery turret. He’s still in good health, lives in Kichijima.

My second oldest brother was then a third-grader. Back then, school evacuations began with third grade. I envied him, thinking that if you went to the countryside, you’d probably be able to eat your fill. But a letter came, and in it he moaned that he was getting thinner and thinner and please send soybeans. So I heard Dad say more than once, “I wonder if we should bring him back.” It was just before the atomic bomb. Had Dad brought him back, they’d have died together in the atomic bombing. Even if you went to the countryside, you couldn’t eat your fill: I realized that keenly.

The death of his father and the others:

What differs about the death of my father from Barefoot Gen is that I myself wasn’t at the scene. Mom told me about it, in gruesome detail. It was in my head, so in the manga I decided to have Gen be there and try to save his father.

Mom always had nightmares about it. She said it was unbearable—she could still hear my brother’s cries. Saying “I’ll die with you,” she locked my brother in her arms, but no matter how she pulled, she couldn’t free him. Meanwhile, my brother said, “It’s hot!” and Dad too said, “Do something!” My older sister Eiko, perhaps because she was pinned between beams, said not a thing. At the time, Mom said, she herself was already crazed. She was crying, “I’ll die with you.” Fortunately, a neighbor passing by said to her, “Please stop; it’s no use. No need for you to die with them.” And, taking her by the hand, he got her to flee the spot. When she turned back, the flames were fierce, and she could hear clearly my brother’s cries, “Mother, it’s hot!” It was unbearable. Mom told me this scene, bitterest of the bitter. A cruel way to kill.

Later Mom instructed me to go back and retrieve their bones, and with my oldest brother, I went back, taking bucket and shovel, and dug in the place Mom specified. My younger brother’s skull was where Mom said it would be. A child’s skull is truly a thing of beauty. But when under a hot sun I held that skull, I felt the cold and truly shuddered. My hair stood on end when I realized his head had sizzled and burned with him not moving at all. Then, in the 4½-mat room we found Dad’s bones, and in the 6-mat room in back, my oldest sister’s bones. A girl’s skull has an expression. Hers was truly gentle: “Ah, even bones have expressions.” Mom said, “Eiko was lucky. She died instantly; hers was a good way to die.”

When we went to retrieve their bones, the stench of death filled the air thereabouts. Because they hadn’t all burned up. There were still bodies lying about. In every tank of fire-fighting water people had jumped in and were dead. What surprised me the most was that right to the end they’d exhibited human emotions: out of love, a mother held her child tight. Her corpse was bloated, swollen from being in the water, and the child’s face was sunk into the mother’s flesh. When I approached Dobashi’s busy streets, corpses filled every water tank. That’s where the pleasure quarter was—they’d all probably still been asleep when the bomb hit. So engulfed in flames, many of them must have jumped into the water tanks. My oldest brother and I decided to return through the city, and Hiroshima’s seven rivers were all full of bodies. As I depicted it in the manga, the bellies were all swollen. Gas developed, and the bellies broke open because of the gas. Water poured into those holes, and the corpses sank.

The thing that horrified me most was that maggots bred and turned into flies. There were so many flies! It became so black you almost couldn’t open your eyes. And they attacked you! Despite the atomic bomb, flies bred. It’s strange, but maggots are really quick. In no time at all they were everywhere. Horrible, really. And that maggots should breed like that in human bodies! If you wondered what that was moving in the sky, it was a swarm of flies. The only things moving in Hiroshima were flames as corpses burned, and flies as they swarmed.

A child clings to mother whose wounds bred maggots

11 days after the bomb. Drawing by Ichida Yuji.

Growing up in postwar Hiroshima

I switched to Honkawa Primary School, and in summers we dove off Aioi Bridge. In the band of urchins, it was bad form not to dive headfirst. If you jumped feet first, they said, “He’s no good.” So even though it was crazy, we dove headfirst. Dive off the railing, and you glided along the bottom. Where there was a river of white bones. Even now if you dig there, you’ll turn up a ton of bones. Those areas have never been swept, and even now there must be lots of bones buried in the sand.

Aioi bridge after the atomic bomb.

The atomic bombing was terrible, of course, but we also suffered afterward from hunger. For a while we stayed in Eba. After the war the food shortage was really severe. At the river’s mouth in Eba, when the tide went out, there stretched an array of rib bones. If you dug under the rib bones, there were lots of short-necked crabs. They fed on the bodies. Lived off of human beings. We gathered the crabs for all we were worth and with them appeased our hunger. Would you say we were blessed by the sea?—there were the seven rivers, and it really helped us appease our hunger.

I was bullied a lot because I wasn’t from Eba. Surrounded by local urchins and called, “Outsider! Outsider!” I had burns, and when I was struck there, bloody pus came spurting out. The brats just laughed. Had it been one on one, I’m confident I’d never have lost, but since they bullied in a group, I had to put up with it. I feel I saw real human nature—rejecting the outsider. Helping each other—that’s an illusion. Because they bullied in a bunch. So I feel I saw the real nature of the Japanese.

Mom was hauled off to the police box for stealing an umbrella she didn’t steal and forced to write an apology. She said, “We’ve got the one room—six mats, so go ahead, search all you want,” but the guy who reported her said, “She’s a sly cat from the city, so I’m reporting her!” I can never forget how Mom was made to write an apology. Had I been an adult, I would have jumped on him and given him a beating, but watching how things went, I felt sorry in my child’s mind for Mom, who was in tears as she wrote, “I’ll never take anything again!” and then signed her name. That guy did it to harass her. I would have been killed had we stayed in Eba, and we had to flee; so scavenging lumber from the military barracks, we built a hut in today’s Honkawa—then it was called Takajo—and set out on our postwar life.

Hiroshima was famous for needles: sewing machine needles, dressmakers’ pins, and the like. Seems there’s an art to sorting these needles. Mom had done it as a child and got work in a reopened needle factory, and that was the source of our postwar income. My oldest brother knew welding from his time as a mobilized student and earned some money working in a local plant. He said, “I wanted to go to the university,” and complained, “Dad died, so I couldn’t.” I found it truly unbearable. But Mom got angry: “There was no alternative!”

In the last analysis I was raised by Mom and my brother. From first grade on I cooked. It was a duty; I had to. It wasn’t like today’s cooking with gas. I worked the bellows to get the firewood burning, then cooked. Sliced sweet potatoes into a bit of rice—that’s what I had to do, my duty. Mom worked. So my next older brother and I took turns cooking.

I entered kokumin gakko [grade school, 1941-1946] in 1945. I was the last to enter kokumin gakko. All my primary school years we lived in Takajo. I graduated from Honkawa Primary School. Since it was the only school that didn’t go up in flames in the atomic bombing, pupils came from all over the city. The ABCC [Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission] came for those pupils. Took the kids off—good research subjects. Picked them up at school by car, then collected the children’s stools for examination. Without parental permission—very high-handed. It began right after the ABCC was established in 1948. Honkawa Primary School students came from all over the city, so they were ideal material for the ABCC. They compared kids who had been evacuated to the country and were healthy with hibakusha, took them both off. In my child’s mind I knew the ABCC was suspect. I thought that if you went there, you’d be given something delicious to eat, but I asked kids who had gone and found they got nothing. My baby sister was named Yuko. For seven years the ABCC team searched the city for her. In the seventh year they found us. “She died at four months,” we told the guy, and he was disappointed. He said, “For seven years we searched for that child.” The ABCC probably needed her because she was born on August 6. The ABCC—it was all about experimenting. They say the dropping of the atomic bomb saved millions of lives, but it was an atomic experiment with the war as pretext. They made atomic bombs of two types and experimented, using the war as pretext. That’s U.S. sophistry. The ABCC didn’t do anything for us.

The Emperor’s Visit to Hiroshima

In my writings there’s a fearsome anger toward power, toward rulers, and I don’t trust people who say nothing about the emperor system. The emperor system–that’s really what it’s about. That emperor system, the horror of the emperor system, still exists today: Japanese simply have to recognize that! And I’m horrified that once again they’re fanning it, pulling it out. I remember well when the emperor came to Hiroshima in 1947. I wrote about it in my autobiography. The school gave the pupils one sheet of paper each. To do what? Take a six-inch compass and inscribe a circle, then color it in with red crayon. Find a piece of bamboo and make a hinomaru flag. I asked, “What are we doing?” They said, “Tomorrow his majesty the emperor is coming; line up on Aioi Bridge.” Dad had told me all about the emperor system, so I thought, “This is the guy who destroyed Dad and the whole family.” I lined up in the front row. A black Ford drove up, and the emperor came wearing a white scarf in the cold wind. In that cold, I was hot as fire inside. “That guy caused us all this, killed Dad,” and I wanted to fly at him. I still can’t forget that impulse. The teacher said, “Say banzai! Say banzai!” “Are you kidding?” With my geta I kicked a fragment of roof tile. It hit the tire and bounced off. I was angry. I’ve never burned so in my whole life. So I remember it well. It was cold, see. In the cold the emperor comes all comfortable. I really wanted to strangle the guy.

Asai: In Hiroshima greeting the emperor, there was virtually no anger or hatred toward the emperor. Why not?

Nakazawa: Because of the prewar education. The prewar education changed the Japanese people completely. I feel acutely how horrible that education was. I’m angry: “If that guy had only swallowed the Potsdam Proclamation, there would have been no atomic bombing.” He survived in comfort, that impudent, shameless guy. Some people did feel the anger I felt toward the emperor, but all of them probably died in prison. I learned from Dad: the emperor system is horrible. When I asked why should Japanese have to bow and scrape so to the emperor, Dad replied, to unify Japan. Turn him into a living god and make people worship him. That system. Since I heard things like that from early on, when I was lined up and made to shout Banzai!, I got really angry. The rage welled up. That feelings like mine didn’t surface in Hiroshima was probably because Hiroshima was conservative. In Hiroshima Prefecture, there really is a prefectural trait—conservatism. Impossible. It’ll be very difficult to change.

Marginalizing the Hibakusha

Asai: Looking at the process in which Hiroshima mayor Hamai Shinzo drew up the Peace City Construction Law and set about rebuilding Hiroshima, I get the sense that it was not a reconstruction that took the hibakusha into careful consideration, that reconstruction took priority.

Nakazawa: It really left the hibakusha out. And in the Mayor Hamai era, virtually everyone was hibakusha, so maybe they couldn’t think about compensation.

Asai: When you consider that the population of Hiroshima, which the atomic bombing had reduced radically, rebounded rapidly after the war, and that the 70,000-80,000 hibakusha didn’t increase, it was the increase of non-hibakusha—repatriates and people coming here from other prefectures—that made it possible for the population to rebound rapidly. In the “empty decade” right after the war it was the non-hibakusha who benefited from the recovery; it was a recovery in which hibakusha were chased to the fringes. That’s my feeling, at least, What do you think?

Nakazawa: You’re not mistaken. And in the process discrimination arose. With the discrimination, it came to be the case that you couldn’t talk about having been exposed to the atomic bombing. You simply couldn’t say publicly that you were a hibakusha. The discrimination was fierce. You couldn’t speak out against it. I was living in Takajo, and I often heard stories, such as the neighbor’s daughter who hanged herself. Discrimination. Dreadful. There were lots of incidents like that, in which people had lost hope.

The Lucky Dragon Incident and the World Anti-Nuclear Movement

Asai: Ota Yoko’s City of Twilight, People of Twilight [Yunagi no machi to hito to, 1955] depicts a group of hibakusha living in one household in Motomachi in 1953. It was reconstruction Hiroshima, with the hibakusha relegated to the edges. And the August 6 commemoration, too: I get the sense that from the very first it was carried out without the hibakusha as main actors. How did you, someone who was there on August 6, feel?

Nakazawa: There was discrimination, and if you emphasized the atomic bombing openly, they’d gang up on you and say, “Don’t put on your hibakusha face!”—a strange way to organize a movement. When there were hibakusha on the Fukuryu-maru #5 [Japanese fishing ship, the Lucky Dragon #5, that received fallout from a U.S. nuclear test at Bikini in 1954] and it became a big issue, Ota said, “Serves you right!” Meaning, now do you get it? That’s how badly hibakusha were alienated.

Yomiuri newspaper reports on the Lucky Dragon #5, March 16, 1954

Even if you wanted to speak, you couldn’t, and if you spoke, the result was discrimination. Discrimination meant they wouldn’t let you complain. An acquaintance of mine proposed to a Tokyo woman, and they celebrated the wedding in Tokyo. And no one came. There was that sense: it’s risky to say you’re a hibakusha. That was what the powerful wanted. Because there was discrimination, you couldn’t say anything: that suited their convenience. Hibakusha were pressured not to assert themselves. Hibakusha first came to the fore at the 1955 World Convention to Outlaw Nuclear Weapons. After all, atomic tests were being carried out one after the other, and death ash was falling; maybe it was the sense of danger that did it.

The World Convention to Outlaw Nuclear Weapons broke up in 1963, and that, too, is a strange story. There were some who made the ridiculous assertion that Soviet nukes were beautiful and all other nukes bad. I couldn’t buy that argument. How can it be a matter of left or right? Doesn’t the goal the abolition of nuclear weapons apply to all?

Asai: At first hibakusha had great hopes of the movement to abolish nuclear weapons, and in 1956 Hidankyo [confederation of hibakusha organizations] also came into existence. But they felt great disappointment and disillusionment at the breakup of the movement to abolish nuclear weapons, were critical of it, and ended up turning their backs on the movement itself. Isn’t that the case?

Nakazawa: Yes, it was. They couldn’t go along with it. People like me felt, “What are these people doing?” If we joined forces for the abolition of nuclear weapons, we’d be twice as strong.

In 1961 I moved to Tokyo and, until Mom died in 1966, thought I’d never return to Hiroshima. Return to Hiroshima, and you experience only gruesome things. So I thought I’d die and be buried in Tokyo. Had Mom not existed, I might have become an ordinary yakuza or fallen by the wayside in Hiroshima; when she died, I’d accomplished something because of her. She played a major role in my life. Her death was a great shock, and I came back to Hiroshima. Thankful for Mom, I sent her body to the crematorium; I thought I knew what a human body that’s been burned looks like. I’d retrieved Dad’s bones and my brother’s bones. I thought I’d get Mom’s skull or breastbone in similar shape, too. But when her ashes came from the crematory and were laid out on the table, I found not a bone. I couldn’t find even her skull. Thinking this couldn’t be so, I rummaged for all I was worth. There were only occasional white fragments. And I got very, very angry: does radioactivity plunder even bone marrow? It made off with the bones of my dear, dear Mom.

Discrimination against hibakusha

I shut my eyes entirely to the atomic bombing, but Tokyoites’ discrimination against hibakusha was awful. If you said that you were a hibakusha matter-of-factly, among friends, they made weird faces. I’d never seen such cold eyes. I thought that was strange, but when I mentioned it to the Hidankyo people, they said that if someone says, “I’m a hibakusha,” Tokyo people won’t touch the tea bowl from which he’s been drinking, because they’ll catch radioactivity. They’ll no longer get close to you. There are many ignorant people. When they told me this, for the first time it clicked: “Yes, that’s how it is.” And I thought, never speak of the atomic bomb again! So for six years in Tokyo I kept silent, and when Mom died and none of her bones were left, I got really angry: both she and I had been bathed in radioactivity, so it made off with even the marrow of our bones. The anger welled up all of a sudden: give me back my dear Mom’s bones! I thought, manga’s all I know how to do, so I’ll give it a try. And it was Struck by Black Rain that I wrote in that anger. I wrote it to fling my grudge at the U.S. Its contents were horrific, but that’s how I truly felt. I wrote it in hot anger and just couldn’t get it published. I hoped to have high schoolers read it. If they read it, they’d understand. So I took it around to the major magazines that aimed at the high school student audience. I was told the content was good but it was too radical, and for a year I took it around. I was about to give up, but I thought again: even if it wasn’t one of the major magazines, wouldn’t it do if it got read? And I took it to the publisher of Manga Punch, the porno magazine. The editor in chief there was a very understanding person, “It moved me greatly.” But, “If I publish this, both Nakazawa and I will be picked up by the CIA.” It was a magazine for young people; “the guys”—truck drivers, taxi drivers—read it.

Within the press, the reaction came back that it was “new.” So it came about that I should write a “black rain” series.

Asai: Did you get reactions from readers focusing on the hibakusha aspect?

Nakazawa: “Did such things really happen?”—people expressed doubts like that. Which means they know absolutely nothing about the atomic bombing. Since I write only about what I had seen; it’s not fiction. But although lots of people say Japan’s “the only country to suffer atomic bombing,” it’s not understood in the least. On the contrary, I was the one who was shocked. I received letters, and they brought me up short. It was virtually the same as when I published Hadashi no Gen: “Is that true?” “Tell us more!”—the vast majority of messages was like that. “I never dreamed that war and atomic bombing were so brutal.”

Barefoot Gen in School Libraries

Asai: Hadashi no Gen is in the libraries of primary and middle schools, and if they take courage and read it, I think they’ll be able to understand Hiroshima better. How do you as author feel about that?

Nakazawa: After all, the overwhelming majority became aware of war and atomic bombing via Hadashi no Gen. In that sense—I don’t pride myself on it—but I’m a pioneer. Even though Hiroshima figures in children’s literature, there’s nothing that takes it that far. I think manga offers the best access. That people are being made aware of war and atomic bombing via Hadashi no Gen: that’s the height of luck for an author.

Asai: Why on earth does the Ministry of Education allow the libraries of primary and middle schools to keep work that’s so anti-war and anti-emperor system?

Nakazawa: I too find it strange. As for manga in school libraries, Hadashi no Gen was the very first. It paved the way. Thanks to Gen, it’s permeated by now to the average person. For me, it’s a delight to think that something I wrote has permeated that far.

Gen dramatized on TV

Asai: It was dramatized recently for TV. I felt then the limits of TV dramatization…

Nakazawa: There certainly are limits. They removed a core issue—the emperor system. Nothing to be done about that. I think the emperor system is absolutely intolerable. Japanese still haven’t passed their own judgment on the emperor system. I get angry. Even now it’s not too late. Unless we pass judgment on such issues….

The Responsibility of the emperor

Asai: Pass judgment—how?

Nakazawa: By a people’s court, actually. The Japanese people must ask many more questions: how much, beginning with the great Tokyo air raid, the Japanese archipelago suffered because of the emperor, how the emperor system is at the very source. To speak of constitutional revision, my position is that it’s okay to change the clauses about the emperor—but only those clauses. The rest can’t be changed. Article 9? Preposterous! Absolutely can’t be changed.

Asai: In your ‘Hadashi no Gen’ Autobiography [1994], you say that as you keep writing about the atomic bombing, you sometimes need to write light stuff.

Nakazawa: When I write scenes of the atomic bombing, the stench of the corpses comes wafting. The stench gets into my nose, and appalling corpses come after me, eyeballs gouged out, bloated; it’s really unbearable. Because I’m drawn back into the reality of that time. My mood darkens. I don’t want to write about it again. At such times, I write light stuff. For a shift in mood.

Radiation Effects

Asai: In Suddenly One Day [Aru hi totsuzen ni] and Something Happens [Nanika ga okoru], the protagonists—second-generation hibakusha—get leukemia. Did such things actually happen?

Nakazawa: It’s possible.

Asai: I’ve heard that as of now the Radiation Effects Research Foundation doesn’t recognize effects on the next generation.

Nakazawa: I think such effects exist. I worry. I worried when my own children were born because I was a hibakusha. I was uneasy—what would I do if the radiation caused my child to be born malformed?—but fortunately he was born whole. I try to have him get the second-generation hibakusha check-up. There’s a medical exam system for second-generation hibakusha; the exam itself is free of charge. But we were uneasy at the time my wife conceived him. We were also uneasy when we got married. Fortunately, there were hibakusha in her family, too, so she was understanding. I worried at the time we got married that there would be opposition. Luckily, people were understanding, and the marriage went off without a hitch. When the children married, I worried secretly. Now we have two grandchildren.

Asai: You met Kurihara Sadako [noted Hiroshima poet/activist, 1912-2005].

Nakazawa: She and I appeared once together on NHK TV. Eight years or so ago. On an NHK Special. A dialog. The location was Honkawa Elementary School. We discussed the experience of the atomic bomb. In broad Hiroshima dialect, Kurihara said to me, “Nakazawa-san, good that you came back to Hiroshima”—that’s how we began.

Asai: I thought Kurihara was a very honest Hiroshima thinker.

Nakazawa: I too liked her. She wrote bitterly critical things. Like me, I thought. She wrote sharply against the emperor system, too. After all, our dispositions matched. But in Hiroshima she became isolated. If you say bitter things, organizations divide into left and right. Even though you’re stronger, if everyone gets together…. Say something sharp, and people disagree, and label you. That no good. The peace movement has to be united. That’s why I never join political parties. It’s something I hate—that Japanese are so quick to apply labels. Immediately apply a label and they say, “he’s that faction or that one,” and dismiss him. No broadmindedness. If a job comes, I respond with an “Okay.” But I never concern myself with political parties.

Asai: How did you come to want to return to Hiroshima?

Nakazawa: Up until ten years ago I stayed absolutely away from Hiroshima. Merely seeing the city of Hiroshima brings back memories. The past. Seeing the rivers, I see in my mind’s eye rivers of white bones. Or the good spots for catching the crabs that grew fat on human flesh. Such memories come back, and when I walk about, I remember, “This happened,” “That happened.” I can’t bear to remember the smell of the corpses. I wanted to stay away from Hiroshima. I can’t express that stench in words. It brings back things I don’t want to remember. This frame of mind of mine is likely the same as for other hibakusha. My former teacher is here, and classmates gather for his birthdays. So I think, “Yes, Hiroshima’s okay.” I have friends here. Time has swept them away, those vivid memories. So I’ve come to want to be buried in Hiroshima. I like the Inland Sea, so I’ll have them scatter my ashes. I don’t need a tombstone.

Hiroshima, Auschwitz and Article 9

Asai: Why can’t Hiroshima become like Auschwitz?

Nakazawa: Japanese aren’t persistent about remembering the war: isn’t that the case? When at Auschwitz I see mounds of eyeglasses or mounds of human hair, I think, “What persistence!” There’s no such persistence among Japanese, not only about Hiroshima. I wish Japanese had what it takes to pass the story on. To erase history is to forget. I’d like there to be at least enough persistence to pass it on. I’d like to expect that of the Japanese. I do expect it of the next generation. I’ve given up on the older generation. I have hopes of the next generation: reading Hadashi no Gen, they’re good enough to say, “What was that?” On that point I’m optimistic. I want them to put their imaginations to work; I absolutely want them to inherit it. I want to pass the baton to them. On this point, the trend in Japanese education today is terrifying. I’m afraid the LDP and the opposition parties will never abandon the idea of educational reform.

But defend Article 9 of the Constitution absolutely. Because it came to us bought with blood and tears. People say it was imposed on Japan by the U.S., but back then the people accepted it, and there’s nothing more splendid. To forget that and think it’s okay to change it because it was imposed—that’s a huge mistake. What the peace constitution cost in the pain of blood and tears! We simply must not get rid of it. That’s been my thinking about Article 9, from middle school on. Precisely because of it, Japan lives in peace. At the time of the promulgation of the constitution, I was in primary school, and when I was told that it transformed Japan into a country that no longer bears arms, will not have a military, will live in peace, I thought, what a splendid constitution! And I remembered Dad. Indeed, what you learn from your parents is huge. Parents have to teach. Not rely on schoolteachers. Teachers ask me how they should teach. What are they talking about? I say they should at least say, “On August 6 an atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.” How to convey that to students in more expanded form: I say that’s the teachers’ function. There are all sorts of teaching materials, so if they don’t do it, it’s negligence on their part.

Asai: That’s hope for Japan; how about Hiroshima?

Nakazawa: The conservative aspects of Hiroshima have to be changed. I think Hiroshima people are really conservative. The numbers of reformists must increase. In order to effect change, each person has to work away at it. I’m a cartoonist, so cartoons are my only weapon. I think everyone has to appeal in whatever position they’re in. Wouldn’t it be nice if we gradually enlarged our imaginations! We have to believe in that possibility. Doubt is extremely strong, but we have to feel that change is possible. Inspire ourselves. And like Auschwitz, Hiroshima too must sing out more and more about human dignity.

The atomic bombing scene of the film Barefoot Gen is available on youtube.com. Click here to view.

Nakagawa Keiji is the creator of the original Barefoot Gen manga series. Four volumes are available in English.

Asai Motofumi is President of the Hiroshima Peace Institute.

He interviewed Nakagawa Keiji on August 20, 2007. An abbreviated translation appeared in Hiroshima Research News 10.2:4-5 (November 2007).

Richard Minear is Professor of History, UMass Amherst and a Japan Focus Associate. He edited and translated Hiroshima: Three Witnesses

Posted on Japan Focus, January 20, 2008.