Suite Slaughter: Inoue Hisashi’s play on the life and death of Kobayashi Takiji

Roger Pulvers

When the Special Higher Police, the dreaded Tokkō, returned his body to his mother and brother, it was hard to believe their official report that he had died of “a heart attack.”

The skin at his temples had been stripped away, and there were 12 wounds from what a physician friend described as “coming from a drill or the needles used by tatami makers,” some on his cheeks. (The police had actually used the metal pokers from a brazier on him.) There were cuts under his chin. His wrists and ankles bore rope marks from his having been suspended from a ceiling; and his lower torso, pubic area and thighs had turned an awful purple color from “relentless beating.” His penis and testicles were bloated and bore the same purple color. There are extant photos of the corpse, taken by his friends as it lay on the floor. The police had even taken the trouble to break his right index finger so that he would never again write a novella like Kani Kōsen (The Cannery Boat).

This was the tragic end to the life of author and agitator, Kobayashi Takiji.

Kobayashi Takiji at work

Recently, there has been a colossal revival of interest in the life and work of Japan’s most famous advocate and practitioner of proletarian literature. Since last year, a reissued volume of stories containing The Cannery Boat has become a runaway bestseller; and a movie based on the story—a remake of one made in 1953—was released in July of this year.

Now, Inoue Hisashi has written a musical that opened on 3 October at the Galaxy Theater (Ginga Gekijō) at Tennozu Isle, Tokyo. “Kumikyoku Gyakusatsu (Suite Slaughter)” presents Inoue’s brilliant, contemporary take on an era when fascism was crushing democracy and overtaking Japan. The very first line of The Cannery Boat finds a fishing industry worker exclaiming to his shipmate in Hakodate harbor, “Hey, we’re all bound for hell!” This is an apt description of Japan’s course in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s.

Kobayashi Takiji, born on 13 October 1903 in what is now Odate City, Akita Prefecture, was raised from December 1907 in Otaru, Hokkaido. (“When I was four,” he subsequently wrote, “on the verge of starvation, we moved to Otaru.”) In April 1916, thanks to some money given the family by his uncle, he was able to enter Otaru Commerical School. He lived in the uncle’s house and worked part time in a bread-making factory. (The opening number of Inoue’s musical is a bread-making song.)

In May 1921, again with the help of his uncle, he went on to high school in Otaru, but at the time he also left his uncle’s house. It was in October of 1921 that the beacon magazine of the proletarian literature movement, “Tanemaku Hito (The Sower)” was founded; and Takiji, barely 18, began writing stories and sending them to magazines. In July 1922 the Communist Party of Japan was formed, and, though illegal, issued its own magazine, “Zen’ei (Avant Garde).”

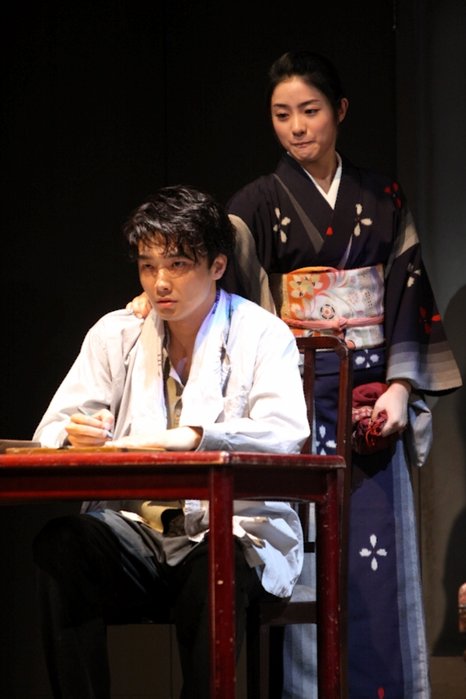

Inoue Yoshio is Kobayashi Takiji, Ishihara Satomi plays Taguchi Taki (Photo by Ochiai Takahito )

After graduating Otaru Commerical College in March 1924, Takiji took a job at the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, whose main branch was in Otaru, first in the accounting department and then in the foreign exchange department.

In October of that year he met and fell in love with Taguchi Taki, whose stepfather had sold her into virtual sex slavery. He began to raise the money to free her, which he finally managed to do in December, 1925.

The General Election Law was established in March 1925, giving the vote to all men 25 or older. This led to a new activism in city and country. It was about this time that Takiji, too, was entertaining the notion of becoming an activist. But it was in this very same month that the Law for the Maintaining of Order was passed, and the government began a clampdown on all leftists. In April 1926, Taki moved in with Takiji. On 20 May 1927, Takiji invited Akutagawa Ryunosuke, among other writers, to Otaru for a public discussion. He certainly thought of himself as a budding author by then.

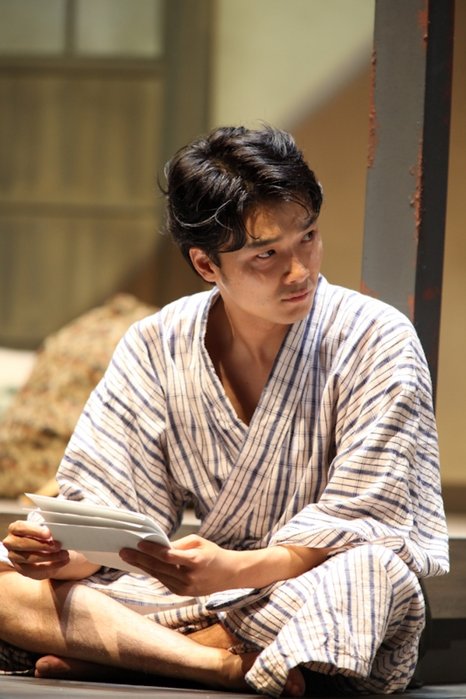

Inoue Yoshio as Takiji (Photo by Ochiai Takahito )

On 15 March 1928, the government of Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi (he was also the foreign minister), which had been hanging on by the slimmest of majorities, arrested over 1500 leftists. Had they been allowed to campaign and agitate, they might very well have come to power in the next election. The Communist Party had been outlawed, but it was openly supporting non-Communist left-wing candidates.

Takiji wrote a novella about the incident under the title 15 March 1928, and Senkisha, a major progressive publisher with its own magazine, decided to publish it. It appeared in the October and November issues of “Senki.” The Cannery Boat was published in the same magazine, in the May and June issues of 1929.

His first stories were met with acclaim from the public, prompting the authorities to either ban them or permit publication with censorship. A story of his from this time—Tenkan Jidai (The Era of About Faces)—appeared in the magazine Chūō Kōrōn with one-fifth of it excised. It is strange now to see some of these stories in the old magazine versions, with scores of XX’s where there should be words.

Three highly popular left-wing magazines of the day—Senki, Kaizō and Chūō Kōrōn—were subject to gross censorship by the state.

And it’s clear why. Kobayashi identified with Japan’s poor, whom he saw as being exploited by laws designed to serve the rich and powerful. The magazine title “Senki” itself stands for “Battle Flag”; and there was no way that the Special Higher Police, who by the late 1920s were clamping down maliciously on all left-wing activity, were going to allow Kobayashi to carry that flag into battle.

“Suite Slaughter” follows Kobayashi from the time he was picked up for questioning in Osaka in May 1930 till his death three years later. Pursuing him are two undercover police, who, in the play, stoop at nothing to get their man. As is characteristic in Inoue’s plays—even the ones that treat such grim, tragic stories as this—there is much light wordplay and some slapstick. At times, these Japanese G-men act more like the Keystone Cops than the dreaded tormenters that they are. One even resorts to dressing up like Charlie Chaplin in a clandestine meeting with Kobayashi (who is also disguised as Charlie Chaplin).

If there is a lightness to his plays, it is the lightness of the German playwright Bertolt Brecht, who used distancing effects such as out-of-character episodes, farcical humor and seemingly absurd turns of events to highlight the core message.

In “Suite Slaughter” Inoue hones in on the era’s overriding theme: the domination of Japan by big money, the emperor and the police. It is clear from early on in the piece that the playwright sees this trinity as a single entity, dragging Japan by the bootstraps toward the destruction of human rights, the invasion of the Chinese mainland and all-out war.

In many of Inoue’s plays, the fates of the victims and those of the victimizers are so interwoven that, at times, it becomes difficult to entangle them. This underscores his humanistic approach to character. The evil actions that humans inflict on others often have their motivations in the psyche of their own past victimization.

Inoue has, in other plays, such as his 1979 play “Shimijimi Nihon—Nogi Taishō” (Deeply, Madly Japan—General Nogi), confronted the issue of the country’s emperors and their responsibility in wartime. In “Suite Slaughter,” too, he does not bypass this. He makes it clear that the march toward fascism is being undertaken in the name of the emperor, and that the policies and laws of the nation that urge it on are just kōmyō na tejina, or “skillful trickery.” The Special Higher Police are referred to here as the law’s banken, or “guard dogs.”

I have been watching and studying Inoue Hisashi’s plays for 40 years now, and “Suite Slaughter” contains some of the most beautiful dialogue I have heard in them.

“There are too many good people in the world,” says his Kobayashi Takiji, “for evil to exist, and too many evil people in the world for good to exist.”

In fact, Kobayashi, despite his arch-realistic descriptions of exploitation of innocent worker by brutal boss, was a kind of romantic. He wrote in a letter to Taki…

“There is darkness, so there is light.”

One of the phases that Inoue puts into Kobayashi’s mouth is “Zetsubō suru na!, “Don’t lose hope!” This ties in closely to another play by Inoue that has been staged for the first time this year, “Musashi.” In both plays the message is that violence achieves nothing but the perpetration of further violence. (The original production of “Musashi,” by the way, is scheduled to tour to London and New York in 2010.)

Inoue Hisashi

Kobayashi, in one scene of “Suite Slaughter,” tells his wife and cohort, Ito Fujiko, to put down a gun that is pointed at the police. The great fight for equality in Japan must be won “by the force of words alone.”

The force of words, however, did not save Kobayashi Takiji. During his lifetime, two of his stories—one of them being The Cannery Boat—were staged. The first play, based on The Cannery Boat, was titled “North Latitude 50 Degrees,” produced by the New Tsukiji Theatre Troupe and presented from 26 to 31 July, 1929 at the Teikoku Theatre. The second was “Fuzai Jinushi (Absentee Landlord),” based on the story of the same title and produced in October 1929 by the Ichimuraza. Takiji, behind bars, was unable to see either of these productions.

When his battered body was returned, director at the Tsukiji Little Theatre Senda Koreya made a death mask of his face. Senda subsequently wrote, “The police used every means they had to block an autopsy, but it was as clear as day by looking at him that he had been the victim of torture.”

Director of “Suite Slaughter” Kuriyama Tamiya, who, incidentally, is Senda’s step-grandson, has said that one of Inoue Hisashi’s primary themes throughout his long writing career has been the question, “Why isn’t the right to lead a normal life given equally to all people?”

Perhaps more than any other play of his, this question is presented so dramatically here that Japanese leaders may finally begin to seriously ask themselves this very question.

If so, the words of Kobayashi Takiji—“Don’t lose hope!”—will resound from the page to the stage, and then, perhaps, to life itself.

After “Suite Slaughter” closes at the Galaxy Theater on Oct. 25, it travels to the Hyogo Performing Arts Center in Nishinomiya (Oct. 28-30) and the Kawanishicho Friendly Plaza in Yamagata (Nov. 1-2).

Roger Pulvers, author, playwright and director, is a Japan Focus associate. In February 2009, he was awarded the Crystal Simorgh Prize for Best Script for “Ashita e no Yuigon (Best Wishes for Tomorrow)” at the Teheran International Film Festival. He is the author and translator of Kenji Miyazawa, Strong in the Rain: selected poems.

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The Japan Times.

Recommended citation: Roger Pulvers, “Suite Slaughter: Inoue Hisashi’s play on the life and death of Kobayashi Takiji,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 42-2-09, October 19, 2009.

See the following articles on related subjects:

Norma Field, Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji’s Cannery Ship

Heather Bowen-Struyk, Why a Boom in Proletarian Literature in Japan? The Kobayashi Takiji Memorial and The Factory Ship

Inoue Hisashi, My Friend Frois. Translated and introduced by Roger Pulvers