Into the Atomic Sunshine: Shinya Watanabe’s New York and Tokyo Exhibition on Post-War Art Under Article 9

Shinya Watanabe talks with Jean Downey

Postwar Japanese Art under Peace Constitution Article 9

The exhibit was in Tokyo from August 6-24, 2008. An exhibit is also planned for Okinawa in 2009.

“Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes. (2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.” Article 9, Japanese Constitution

For sixty years, Article 9, the Japanese Constitution’s Peace Clause, has played a critical role in Japanese politics, in US-Japan relations, and may have served as a brake on nuclear arms proliferation in

Shinya Watanabe sought to heighten American awareness on these issues by bringing ”Into the Atomic Sunshine: Post-War Art under Japanese Peace Constitution Article 9,” an art exhibition that included two artists censored in Japan, to the Puffin Room Gallery, in the SoHo district of Manhattan, in January and February 2008.

The Japanese-born, New York City-based curator might easily be typecast as a spiky-haired, young Japanese interested only in manga and hip clothing, but he is, instead, an intellectual deeply engaged with the world. The impetus behind his exhibitions goes back to a life-transformative period at the age of twenty, while an economics student at

As a curator, he has committed to exploring critical public issues, especially the historical relationships among nation-building, militarism, colonialism, and war, and to exploring the possibilities of a more peaceful world order. His master’s thesis examined the influence of nation states on art, looking at Yugoslavia after the collapse of the USSR and became his first exhibition, “Another Expo: Beyond the Nation-State,” which opened in Japan on August 15, 2005, the sixtieth anniversary of the end of World War II.

I met Watanabe at the Puffin Room, a socially engaged public art space overflowing with historical and contemporary reminders of the pervasiveness of war in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Prior to “Into the Atomic Sunshine,” the gallery exhibited Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the Japanese American incarceration from Linda Gordon’s and Gary Okihiro’s book, Impounded. “Shock and Awed,” Puffin’s permanent exhibition of Iraqi children crayon depictions of “Operation Iraqi Freedom,” was concurrently displayed on the lower-level gallery.

After a tour of the exhibition, Watanabe and I continued our conversation at the home of New York-based Greek artist, Lydia Venieri, whose “No Evil” series will be exhibited in

These are not new issues, of course. Ordinary citizens in

Detractors in both

Although its letter and spirit have been stretched over six decades, Article 9 and Japanese civil society’s support for its pacifistic principles continue to check the government’s militaristic ambitions. Article 9 stands in the way of the export of weapons, the possession, production and import of nuclear weapons (the three non-nuclear principles), and the deployment of the SDF abroad for active combat. To underscore the last point, supporters repeat that Japanese troops have not killed a single person overseas since the Second World War, in sharp contrast to the succession of Japanese wars over the previous half century.

In response to the heightened attacks on Article 9 that began under Abe’s predecessor, Koizumi Junichiro, democratic activists, across diverse sectors of Japanese society, have mobilized in recent years. In 2004, eminent Japanese scholars and writers, including novelist and activist Oda Makoto, philosopher Tsurumi Shunsuke, and Nobel laureate Oe Kenzaburo founded The Article Nine Association (Kyujo no Kai). American filmmaker John Junkerman, participant in the “Into the Atomic Sunshine” discussion platform and director of the 2005 “Japan’s Peace Constitution,” noted that popularization of Article 9 has begun to spread, as the result of spontaneous grassroots support inside and outside of Japan. (See a Japan Focus article on the subject.) In 2005, the Peace Boat, a Japanese peace, human rights, and environmental NGO, and the Japanese Lawyers International Solidarity Association (JALISA) organized the Global Article 9 Campaign, now supported by over sixty Japanese civil society organizations, and hundreds of NGOs worldwide. In May 2008, the “Global Article 9 Conference to Abolish War” will convene in

Understandably, Japanese artists have critically addressed issues of war and peace throughout the postwar period. In the 1990’s, several artists were censored in Japan because their unflinching artistic criticisms of imperial Japan’s wartime record raised the ire of right-wing groups that used violent intimidation tactics against the galleries, museums and communities that sought to present the artists and their work. In order to work without inhibition, some artists, including Berlin-based Yoshiko Shimada, moved abroad. Others, such as Oura Nobuyuki, featured in the “Into the Atomic Sunshine” exhibition, had to change careers. In 1995, Yanagi Yukinori became the first fine artist to specifically address Article 9. Watanabe included his installation, “The Forbidden Box,” in the “Into the Atomic Sunshine exhibition” as a tribute to his groundbreaking and provocative work.

The content of the other late twentieth and early twenty-first century artworks Watanabe selected for this show also reverberate images of national identity, political theater, imperialism, war, dehumanized “Others,” and the universal yearning for peace. Watanabe chose not only Japanese but also American, European, and Latino artists, most with transnational backgrounds, who combine issues that may seem disparate at first glance. These artists confront European, American, and Japanese colonialism, wartime atrocities, the atomic bombings, and

Shitamichi Motoyuki, “Untitled (Torii)”

Photographer Shitamichi Motoyuki‘s haunting photographs of colonial-era Shinto shrine remains in Japan’s former colonies graphically remind viewers that, only six decades ago, millions of people throughout Asia were forced to worship shrine and emperor under Kouminka (imperial citizen forming) policies. Morimura Yasumasa’s videowork “Season of Passion – A Requiem: MISHIMA” brings an unexpected and uncanny twist to Mishima Yukio’s speech at his failed 1970 coup d’etat attempt. Watanabe included this work partly because Mishima also called for the abolition of Article 9.

In their 2007 “Unrealizable Goals,” videowork filmed at Kita-Kyushu, the initial target of the

Tokyo-based, Belgian artist Eric van Hove also refers to

Watanabe commissioned American Vanessa Albury’s “Your Fears, My Hopes” specifically for “Into the Atomic Sunshine.” Albury’s work aims to focus attention on shared collective and individual trauma, and, like Yoko Ono’s “Play It By Trust,” the centerpiece of the exhibition, reflects a yearning for healing from the wounds of war-filled world history we all have inherited and must work out together, and a longing to somehow transform the violent mental and emotional attitudes that result in the creation of weapons, soldiers, military-industrial states, and war.

—–

JD: How did you conceive the Article 9 exhibition?

SW: Article 9 is one of the biggest issues in

I know both countries,

JD: You took the title of this exhibition, “Into the Atomic Sunshine” from a remark made by General Courtney Whitney at the 1946 conference that created the Japanese constitution. Whitney, head of the Occupation’s Government Section and a key figure in drafting the Constitution, told a Japanese translator, “We have been enjoying your atomic sunshine.” The conference was actually nicknamed the “Atomic Sunshine” conference. What do you think Whitney meant by this charged combination of words?

SW: General Whitney’s comment made it clear to the Japanese who was the winner and the loser of the war. He remarked that accepting the GHQ draft would be the best way to keep the emperor “secure” and made plain that if the Japanese government did not accept this plan, then General MacArthur would propose it directly to the Japanese people.

JD: You did more than curate an exhibition around the concept of Article Nine. There were a series of events organized around the exhibition as well. Why did you choose these events?

SW: Before curating an exhibition, I always organize a discussion event, which I call a “platform.” I got this idea from Documenta 11, the large art exhibition in

Before curating this exhibition, I wanted to discuss Article 9 and its meaning. The discussion helped me to find ways to curate the exhibition from multiple perspectives, both inside and outside of

The film screening of Steven Okazaki’s White Light, Black Rain was significant. This was the first documentary of the atomic bombings of

After the film screening, the Vangeline Theater performed Butoh, a contemporary dance form recognized worldwide as an important artistic expression that emerged from Japanese postwar culture. To see the Butoh performance by an American troupe right after the documentary of the atomic bombings was very powerful.

The live music event featured Miho Hatori, a member of the musical groups, Gorillaz and Cibo Matto. I asked Miho-san to sing songs from Okinawa, since Okinawa’s current situation as an

JD: How did you choose the artists for the exhibition? Were all the artists supporters of Article Nine?

SW: Not necessarily. I included some artists and artworks directly focusing on that issue, including Yukinori Yanagi, Eric van Hove, and Allora & Calzadilla. But other works demonstrated the historical context of Article 9 and the circumstances of Article 9’s creation, or reflected the philosophy of Article 9.

Oura Nobuyuki, “Holding Perspectives”

JD: The most controversial artist in the exhibition is Oura Nobuyuki, who was censored by the

After a successful 1986 exhibition that included this series, the museum purchased four pieces from Oura, and, in 1990, republished a catalog from that exhibition. It was the year the emperor died. The controversy started when a local Shinto priest publicly ripped the catalog apart at the

Your exhibition catalog describes Oura’s work not as an attack on Emperor Showa, as ultranationalists charged, but rather an investigation and critique of

You also assess Oura’s importance not only in terms of artistic resistance, but also as a bellwether of political resistance against the revival of ultranationalists calling for the re-deification of the emperor. Oura and his supporters have held countless meetings, published pamphlets, articles, and books, and have “raised the level of political awareness among artists and writers, all of which sounded a warning against the conservative revival.”

Oura isn’t able to exhibit in

SW: He no longer works as a fine artist. Instead, he has become a filmmaker in

His recent film “9.11-8.15 Nippon Suicide Pact” is about postwar

Oura is still active as a film director, but the “Oura Incident” itself is not known outside of

“The Forbidden Box” by Yanagi Yukinori

(Photo by Takamatsu Yuka)

JD: Yanagi Yukinori was also censored in the 1990’s by a gallery in

His work has a strong transnational and universal orientation. He is from Fukuoka, and said that living so close to Korea while growing up formed his concept of porous borders. Does he exhibit in

SW: Yes, he is active in

Camp Berlin, “Orizuru Problem Project” |

JD: The exhibition “

SW: A project which I am especially interested in is the recycling of orizuru (origami cranes). Because of the story of Sadako and the thousand cranes, Hiroshima-City receives millions of orizuru from all over

The German artists came up with some recycling plans, but these plans have not yet materialized. Mr. Yanagi felt the ideas of German artists were not yet profound enough, because of the difficulty in grasping the massive quantity of orizuru. At the same time, this is above all a cultural exchange project. So if German artists are able to dialogue with Japanese artists about the issue of

JD: Yanagi’s “The Forbidden Box” uses a box as a symbol merging the Greek myth of Pandora’s Box with the Japanese folktale, “Urashima Taro.” He explained that he wanted to invoke a sense of universalism in this piece: “In our travels around the globe and living in different cultures, I have found it hopeful to learn that the myths and legends which we transmit to our children through the ‘folk’ or ‘fairy’ tales we share with them, have universally common themes no matter whether the stories originate in Asia, Europe, Africa, or the Americas. This universality of children’s tales enables us to know that we, as a species, share common core values and hopes all around the globe. From this we can learn anew that we are sisters and brothers who share a fragile globe, and that we must care for one another and our dear ‘Mother Earth.’” Yanagi said his work also embodies an allegory for modern Japan, that the atomic bombings opened a Pandora’s Box of human tragedy and a chain of historical events that unexpectedly included a “hope” for

SW: Yanagi Yukinori creates beautiful, yet controversial works which refer to postwar Japanese history, encompassing issues of the imperial system, the fear of nuclear weapons,

In 1995, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the

Mr. Yanagi evokes the image of

“The Forbidden Box” is the first fine art collaborative work between American art institutions – the Fabric Workshop and Museum in

The “hope” that you mention reflects the “hope” of atomic bombing survivor anti-nuclear activists who strive to assure that there will be no future victims of nuclear bombings. Article 9 is a renunciation of war, whose premise is that

JD: The cancellation of the Smithsonian atomic bomb exhibit reminds us that censorship of representations of World War II has occurred on both sides of the Pacific, and that neonationalist pressure is by no means restricted to

This exhibition, which was to open in 1995, was to include the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the atomic bomb on

SW: When Yanagi created this artwork for the 1995 exhibition “Project Article 9” at the

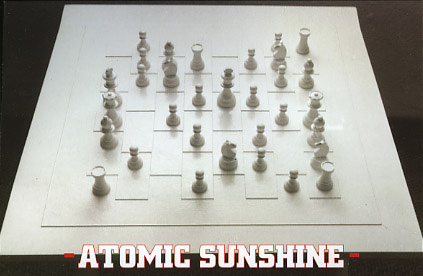

JD: Yoko Ono’s “White Chess Set,” first conceived in 1966, and also known as “Play It By Trust,” is the center of your exhibition. There are no black chess pieces, only white pieces, thereby eliminating the idea of an opponent or “enemy.” As the players get further in to the game, it becomes increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish whose pieces are whose. The idea of “us” and “them” becomes erased. You wrote in the exhibition catalog that Yoko Ono was the first artist to “invert the notion of chess, to make it a metaphor for peace, rather than a game of conflict.” This conceptual artwork is better known as “Play It By Trust,” renamed for a 1987 tribute version created for the 75th birthday of composer John Cage. Would you speak about it and Ono’s involvement with Article Nine and peace activism?

SW: To be honest, I do not know her exact opinion on Article 9. However, her “Peace Art” aims at perfect and absolute peace, which is completely different from any other artist I know.

First of all, chess is a war strategy game. When the Great Tokyo Air Raid took place in March 1945, Ono was forced to evacuate from

Having grown up both in

I think that John Lennon’s message on peace came from Yoko’s influence. My understanding is that John Lennon became a media advocate because of Yoko, to help broadcast her message of peace.

JD: Would you comment on German-born, San Francisco-based

SW: Ezawa created an animated video work, drawing on the 1966 film Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in 2003, just after the beginning of the

Edward Albee wrote “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” in 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis. George and Martha represent George Washington and his wife Martha Washington, and Nick who appears in the film represents Nikita Khrushchev.

The film Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? also referenced the 1933 Disney animated film Three Little Pigs, known for its theme song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf,” based on the Grimm Fairy Tale, which does not have a structure of right and wrong.

The Three Little Pigs theme song, “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” became a best-selling song, mirroring people’s resolve to overcome the “big bad wolf” of the Great Depression (the Japanese constitution was written by American New Dealers of this era). When the Nazis began conquering their neighbors, the song also came to reference the dark situation of

Ezawa’s title “Black, White and Gray,” seems to me to deny the dualism between winner and loser, represented by the colors black and white. Furthermore, black and white are colors that represent racial division, and gray might represent the position of the artist, who was born in

In the last scene of this video work, when George tries to shoot Martha, an umbrella pops out from the rifle. As the umbrella inflates, the tension deflates.

JD: You chose informed, engaged, and courageous artists who spoke and speak truth to power. Oura did so, with devastating professional consequences. Some Japanese neonationalists have no respect or tolerance for freedom of expression. Do you think they overestimate the power of art? Are artists able to influence or even change society?

SW: I think that artists do not have the power to change society, but artists can touch the hearts of individuals, and can influence individual acts. Even across great distances, the message of the artist can reach individuals. That is the power of art.

The job of the artist in society is to speak about ideals. In this way, for example, John Lennon did important work in creating the song “Imagine.” That was a perfect message about ideals, and it was a message to the people, that touched many individually.

Now, because of inhibitions from the commercial art market that artists must deal with, artists face limitations in opportunities to express real ideals. But as long as the artist works as an artist, I believe that the artist will talk about societal ideals, and I want to work with these artists.

JD: I see what you’re doing as critical curating. Your worldview actually seems alt-global, and the artists you work with are fine artists, but they hold critical and alternative perspectives.

SW: I think so. I am also drawn to the universal. The twentieth century was a century of war, dominated by a very idée-oriented, male-oriented society. I think the twentieth-first century needs to be more universal, khora-oriented, and somehow more feminine.

I think of modernism itself as negentropy (saving information in an efficient way). This negentrophy of modernism appears as the microchip, nuclear power plants, or nuclear weapons. These are examples of the mindset of modernism that reached its zenith in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The nation-state is also a product of modernist thought.

I wanted to show alternative philosophical approaches that can help us overcome the type of thinking that characterizes modernism, which was created mainly from Cartesian philosophy.

JD: Would you talk a little about postwar Japanese art and how it differs from prewar art?

SW: First of all, in

I like the word “postwar,” since this word implies that war is over permanently. However, the current situation in

Postwar Japanese art contains much conceptual artwork, often involving the mixture of Japanese tradition with American influence.

JD: Why did you come to the

SW: Actually I wanted to go to

I thought the position of Habermas, a German intellectual, could be helpful for

The reason I came to NYU was that, number one, my English was a lot better than my German, and number two,

KM: How did you become a curator?

SW: I wanted to go to art school when I was in high school, but my father ran a small fish company in a rural part of

When I was twenty-years-old, I had a chance to travel all over Asia, seven countries by land, and I tried to make a documentary film about

JD: What did people want to talk about?

SW: They talked about the harsh experience of changing their names into Japanese and being forced to speak and write in Japanese.

JD: Did you finish the film?

SW: I tried to finish the editing many times. I edited with Sony’s VAIO, but the computer was not powerful enough to complete it. On TV, the Sony VAIO commercial said, “If you buy this computer, you can make a film!” But to make a film with this computer was just impossible. So my friend said, “Just forget about your film. Let’s watch a good film at Athenee Francais.”

There, I saw a film by Chris Marker. He is a French director, part of the Nouvelle Vague (New Wave), and part of the May 1968 Revolution in

JD: Why?

SW: Because Level One was the beginning of the war, and Level Two was close to genocide, the raping of women, acts like that. And Level Three was worse. In

This was very significant to me. I wanted to complete a war film on

I thought that if I became a curator, I could introduce very good artwork in certain contexts. I’m good at this. So I decided to become a curator when I was twenty-one.

JD: Your interests were so profound at a young age.

SW: When I traveled and began making exhibitions, it was almost as if I was driven by some kind of strong will from deep inside of me. In Japanese, this kind of feeling is called “moved by the heart.”

JD: Do you know exactly what it was moving you? The themes you work with are about universalism, war, and peace.

SW: I guess it starts largely from my grandfather’s wartime experience. My grandfather was sold to a fisherman’s community as a slave. It is a typical story of the 1920’s and 1930’s, as in “Izu no Odoriko” by Kawabata Yasunari, or poems by Serizawa Koujiro. This experience in my ancestry probably moves me to go to in that direction.

JD: You’re planning to take this exhibition to

SW: There have been exhibitions of “peace” art. However, this would be the first exhibition that includes historically important fine artists with critical perspectives addressing Article 9. By bringing this exhibition from

—-

Spikyart.org, Shinya Watanabe’s website contains more information and photos from “Into the Atomic Sunshine: Post-War Art under Japanese Peace Constitution Article 9.” The exhibition catalog, with a detailed history of Article 9, a summary of the discussion platform with participants John Junkerman, neonationalist political critic Suzuki Kunio, Beate Siroto Gordon, and Japanese economics scholar Frances Rosenbluth, and descriptions and photographs of artwork, is available at Amazon.com.

Jean Miyake Downey, a lawyer, sociologist and contributing editor for Kyoto Journal: Perspectives on Asia, writes on multiculturalism and human rights issues. She conducted this interview for Japan Focus. Posted on March 17, 2008.

See Edan Corkill’s extended review of the Tokyo exhibit, “Making art out of Article 9, and his reflections on Japanese artists abroad, here.