If Araki Nobuyoshi likes you, he will take you to the cramped bar he owns in the Kabukicho red-light district of

This is the nighttime lair of perhaps the planet’s most prolific photographer of the female form, a man dubbed a misogynist, a porn-and-bondage-merchant and a genius, so you expect the outré and Araki doesn’t disappoint. The bar is wallpapered with Polaroid snaps of women: young, older, ripened by years in the water trade, some pigeon-toed and shy; others spread-eagled or violently hogtied, thrust up like Sunday roasts and skewered by his camera.

The middle-aged mama-san Araki employs to serve drinks flits about in a classy kimono, oblivious.

A visitors’ board records the celebrities who have come to pay homage. Bjork, who commissioned Araki to photograph her 1997 album cover Telegram, is there along with controversial Kids-director Larry Clark. “Thank you 4 a lovely day. U R a dirrrty devil,” says one of the more printable comments. The master himself dominates the room with the jittery, uncoordinated energy of a teenager, cackling at his own dirty jokes.

“Be careful of walking around and banging into things with that big cock of yours!” he shouts, as I stumble in the cramped space. Earlier he had told my bemused female companion some of his photographic techniques. “I sometimes blow into the breasts of women while I’m photographing them, to make them look bigger,” he says before exploding in laughter.

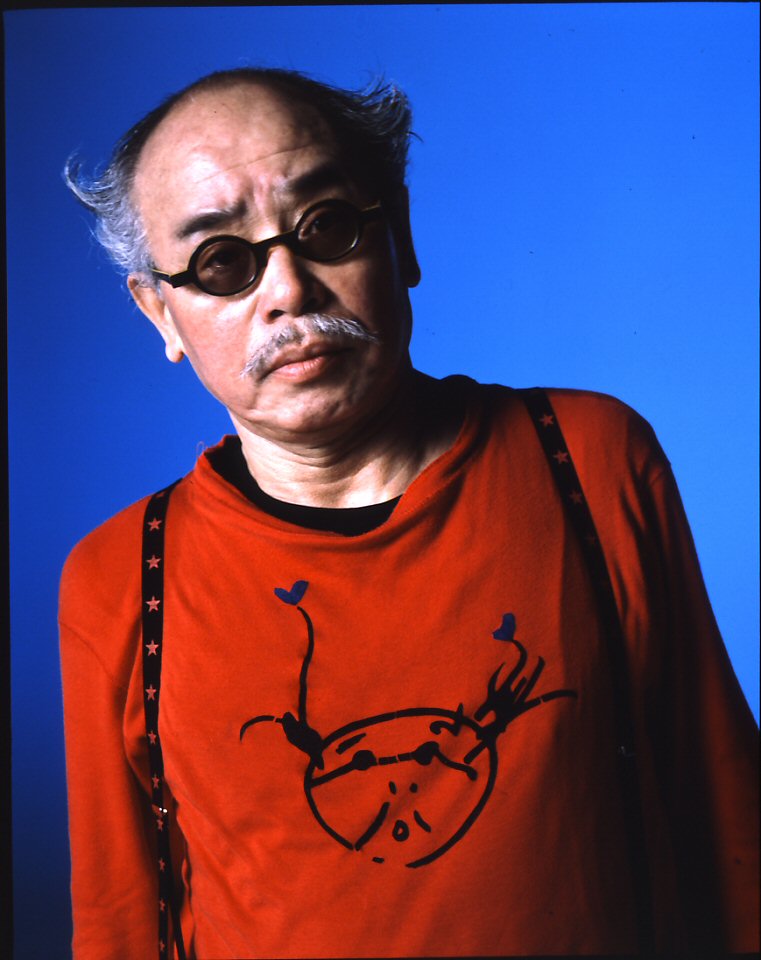

Araki Nobuyoshi

But visiting this bar is to merely sip stale water at the grand banquet of Araki’s work, which includes thousands of exhibitions and 350 books, an output he adds to at the staggering rate of 10 every year. His photos are always on display somewhere: a new collection runs at the Barbican in

Perhaps his greatest work of art, however, is the iconic tuft-haired Araki himself, a man so famous in

Not surprisingly, perhaps, Araki hates most modern photography. “When I look at photos I see no eros or passion. It doesn’t matter if it is a picture of a city landscape, or a woman or

Araki can sometimes be spotted at night, walking around Shinjuku and talking to well-wishers.

From the collection at the Barbican in

He has photographed other places, and even men, but it is

Although often asked about his next projects, he never plans what he will shoot from one day to the next, and lives in the expectation of chance encounters. “I’m happy in the moment, when I meet someone new and I think we might hit it off. I know nothing about long-term happiness, only what I’m doing right now.” The sexual chemistry of those encounters is what makes a great photo, he believes. “You cannot put into words why you take photos, or what you’re doing when you’re taking them.”

Those libidinous instincts – calling it a philosophy might be pushing it – once made him one of the more shocking and transgressive photographers alive, though the days when a spread-eagled female body could bring the police calling are gone. Many of his photos are scattered around the Internet, along with much worse. Araki claims he never goes online. “I don’t even have a mobile phone.” His motivation, in any case, was never to challenge social or cultural rules, he explains. “I have no interest in changing society, though I might have changed two or three women in my time. I guess I’m stingy; I just don’t want to waste my time on other people. But if somebody says not to do something, it makes you want to do it all the more, right?”

Araki’s work, though, still unsettles, paradoxically – for a man who puts such store in the human warmth between photographer and model – because of the merciless, cold stare of his lens. Nothing is beyond the viewfinder’s unflinching gaze. He famously photographed his entire life with beloved wife Yoko, leaving little out: from their honeymoon and lovemaking to her struggle with cancer, and her cremated bones on a steel gurney.

From the collection at the Barbican in

The best of his work goes well beyond female objectification and has a pathos that may help it outlive the pornographer tag, such as when Japanese poet Miyata Minori displays the surgery scars from the cancer that will eventually kill her.

Miyata Minori

His latest collection (“6X7 Hangeki”) includes its fair share of pliant, demure young things, but many of the older women stare back at the camera with a mixture of defiance, anger, openness, perhaps affection for the cherubic little man at the other end of the lens. As Guardian critic Adrian Searle recently put it, for Araki, faces are the real private parts.

“I’m trying to catch the soul of the person I’m shooting. The soul is everything. That’s why all women are beautiful to me, no matter what they look like or how their bodies have aged.” Bjork was one of his most memorable shoots. “Half virgin, half old bag, like a shaman…what a face,” he remembers.

Araki’s Bjork

For a man whose libido is so firmly bound up with his art, Araki is surprisingly unfazed by the prospect of decrepitude. He has no fear of getting bored of the camera or being unable to work. “Taking pictures is as natural as eating and then taking a dump for me. It has nothing to do with age. I never think about it, and I’m very diarrheic,” he cackles, then hits again on my female companion. “Be my wife for a day,” he pleads. “Let’s ditch this joint.”

His work is included in “Seduced: Art and Sex from Antiquity to Now,” which runs at the Barbican Art Gallery London from

David McNeill writes regularly for a number of publications including the Irish Times and the Chronicle of Higher Education. He is a