Family Ties: The Tojo Legacy

By David McNeill

The granddaughter of Japan’s wartime leader Tojo Hideki has become one of his staunchest public defenders since emerging from obscurity a decade ago. But exactly who is she and why has she come in from the political cold?

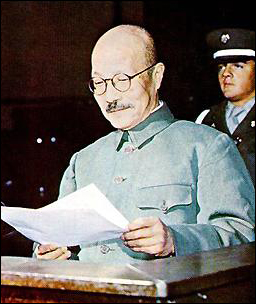

There is no mistaking the impact of the family genes on Tojo Yuko: she has the same myopic, almond-shaped eyes, thin mouth and wide cheekbones as her grandfather, General Tojo Hideki, who led Japan to disastrous defeat in World War 2. She even affects his rigid military bearing.

Ms. Tojo clearly idolizes her grandfather, who was executed as Japan’s top war criminal in 1948: she often comes to interviews with foreign journalists carrying a box of mementos that include nail clippings, a lock of hair, and the butt of the last cigarette the general smoked while awaiting the hangman’s noose in Sugamo Prison.

Contrary to those who put Tojo in the small club of World War 2 monsters along with Hitler and Mussolini, she says the man who ordered the Pearl Harbor attack led a “war of freedom” in Asia. “Essentially he was a kind man who loved peace,” she says. “He was defending his country against foreign aggressors. His greatest crime was that he loved his country.”

In another time or place, Ms. Tojo might be considered a harmless relic, or have opted to remain living anonymously under her real name, Iwanami Toshie. But 60 years after the end of World War II, this tiny woman with impeccable manners and the air of a retired school teacher is one of the most toxic figures in a growing historical revisionist movement that is again pulling Asia apart.

The revisionists have already sparked a storm of protest by publishing school textbooks that gloss over Imperial Japan’s worst war crimes. Now they risk further confrontation with an increasingly powerful and assertive China by pushing for annual prime ministerial visits to Yasukuni Shrine, which many consider a memorial to unrepentant militarism.

In the months leading up to the 60 th anniversary of Japan’s surrender in August 2005, Ms. Tojo was exceptionally busy, giving long interviews to members of the Japanese and foreign press, including the Arab satellite news channel Al Jazeera, the British Financial Times and several South Korean media outlets. On August 15 th, she was widely photographed at Yasukuni Shrine, grim faced, alone, and holding a large portrait of her executed grandfather.

The Yasukuni photograph, taken on a day when the shrine hosted 200,000 people including Tokyo Gov. Ishihara Shintaro, then LDP acting General Secretary Abe Shinzo and heroes of the right such as Onoda Hiroo,[1]captured Ms. Tojo in her favorite pose: the stubborn patriot, sotto voce, battling against Japan’s political establishment to rescue her grandfather, and, by implication, the millions of soldiers he led, from the dustbin of history. She reinforced this position later that day when she publicly berated Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro for breaking a promise to visit the memorial.[2]

On inspection, however, Tojo is very much a child of the establishment, albeit a wing banished to the political margins during Japan’s US-sponsored Cold War heyday. Her reemergence after over quarter of a century of quiet domestic life is evidence that her brand of recidivist ultra-nationalist politics has been re-embraced by elements of the Liberal Democratic Party and the various fringe political, religious and cultural satellites that hover around it.

The project that unites them is straightforward, if unsettling: reverse the decisions of the Tokyo Tribunal; annul the current constitution, especially the hated Article Nine; radically revise the educational curriculum and reposition Yasukuni as a core element of state ideology. If successful, it amounts to nothing less than a conservative revolution — an attempt to roll back much of the last half-century of liberal gains in Japan.

Tojo was born in 1939 in Japanese-occupied Seoul to Tojo Hidetaka, the general’s eldest son. She remembers little of her grandfather, who became prime minister in October 1941, except that he was “kind but stern” and had little time to spend with his family. After the war ended, the family moved to remote Ito in Shizuoka Prefecture under the protection of sympathizers, where she and her brothers were bullied; an unhappy period that profoundly shaped the psychology of a young girl not yet in her teens. She later wrote of hearing adults whisper the word koshukei [death by hanging], and of watching in horror as other children mimicked her grandfather’s death.

Tojo claims that her family name “ was untouchable for 50 years,” but the family appears to have prospered and wielded power in corporate, military and public affairs realms. The general’s second son, Tojo Teruo, is a former vice president of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and chairman of Mitsubishi Motors who designed aircraft during and after the war. Youngest son Toshio was a major general in the Air Self-Defense Forces. Daughter Mitsue married Sugiyama Shigeru, who became head of Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force. Tojo says her husband was a TV producer at state broadcaster NHK for over 30 years before becoming a university teacher, and her younger brother, Takayuki, is a former president of Japan Victor in Germany.[3]

Tojo quit Meiji Gakuin University in her twenties to marry, and had four children. One of her daughters today lives in the US and is married to an American who works for Boeing Corp. Tojo harbors little of the obvious anti-American sentiment of some on the right in Japan: when told recently by her distraught daughter that her son-in-law would soon be going to Iraq to work, Tojo told her it couldn’t be helped because “one had to defend one’s country.” During the Tokyo trials, her grandfather was “very impressed” with his American lawyers. “Those people treated him with great respect and he respected them, even as enemies,” she says.

When her children were older, she enrolled in Kokushikan University to take a degree in education, where some speculate she was courted by right-wing lobby groups such as the Nihon Kaigi (The Japan Conference). After graduation in 1988 she came out of the political closet and began speaking on platforms for popular nationalist causes, among them the retrieval of fallen Japanese soldiers abroad, the reinstatement of a national holiday for the Showa emperor and official state visits to Yasukuni.

She also formed an NPO called the Environmental Solution Institute (http://www.epo.or.jp ) and began researching a book about her grandfather. There is some uncertainty about what ESI actually does – in an interview with this author Tojo claimed it markets products and fights for environmental protection laws. Its homepage lists Tojo (under her real name, Iwanami Toshie) as president and various family members and known right-wing figures as directors.

These include Kamiya Kotoku, who is also chairperson of a support organization for Seicho no Ie, [Truth of Life]; a Shinto cult established in 1930 and reformed in 1949, it campaigns to replace Japan’s postwar constitution. Boasting five million members worldwide, its supporters include ultra-right author Suzuki Kunio and other members of the revisionist right in Japan.

Another member of Tojo’s NPO, Kai Isamu, is director of a memorial to General Tojo and six other A-class war criminals as well as over 1,000 B&C-class criminals called Koa Kannon in Shizuoka Prefecture. Tojo is also listed as a supporter of several right-wing organizations, including the Society for History Textbook Reform and the Showa Day Promotion Network, a lobby group that long campaigned to have the Green Day national holiday on April 29 th declared Showa Day in honor of Emperor Hirohito. In May 2005, the Diet approved the bill making Showa Day a national holiday.

Other groups that form part of the matrix of support for Tojo include ultra-conservative lobby group Nihon wo mamoru kokumin kaigi (The National Association for the Protection of Japan), now merged with the Japan Conference, the Association for the victims of North Korean Abductions (Rachi higaisha no kai) and the Japanese War Bereaved Association (Nihon izoku kai) an organization claiming one million members that has been widely credited with being the most important political force behind Koizumi’s Yasukuni visits. Such connections put her in the political orbit of many senior LDP figures, including Foreign Minister Aso Taro, Chief Cabinet Secretary Abe Shinzo and former trade minister Hiranuma Takao.

In 1992 Tojo published a book, Issai kataru nakare – sofu Tojo Hideki ichizoku no sengo [lit. Never Talk: The Postwar Life of Tojo Hideki’s Family]. In 1995 she wrote a fawning memoir, My Grandfather Tojo Hideki. The book upset some of her family who disliked being dragged back into the political spotlight, but it sold over 120,000 copies and became the basis of the landmark revisionist project Pride, one of the highest grossing Japanese movies of 1998 [4] She published a second volume of family memoirs called Tojoke no hahakogusa [The Tojo Family’s Hahakogusa] in 2003.

Tojo’s decision to go public coincided with a period of profound transition in Japan as the giddy economic achievements and hubris of the 1980s gave way to decline, political stagnation and national soul-searching of the 1990s. The name Tojo was a rallying point for some on the right who looked for answers to these problems in a semi-mythologized past, when Japan was strong, independent and answered to nobody. As Japan’s crisis deepened, the issues buried beneath the expedient postwar political settlement bubbled back to the surface like untreated sewage, and she gave them a voice.

All this is not to paint a picture of a united or even cohesive right-wing project to drag Japan back to the past. Many in the LDP find Tojo’s pronouncements irritating; given the number of times she has called Koizumi ‘gutless’ she is unlikely to be invited to the prime minister’s residence any time soon. Few establishment politicians publicly share her opinion that the emperor is “the essence of Japan” (see interview below) and some are likely to be unsympathetic, to put it at its mildest, to her staunch defense of Imperial rule during the slaughter of the 1930s and 40s. Even among the ultra-right she has inherited the fractious politics of the past along with her family name: Her grandfather uneasily straddled the political and military worlds (as prime minister and head of the military) and he eventually purged the most extremist elements of Kodo-ha (The Imperial Way Faction), earning him the lasting animosity of its modern followers.

Still, she articulates a set of views that resonate in a country floundering since the end of the Cold War and spooked by the rise of China: resentment at the outcome of the Tokyo trials and the legacy of victor’s justice; disdain for the nihilism of contemporary Japanese life; distrust and dislike of Beijing and of the bureaucratic parlor games of diplomacy; a preference for a more muscular, independent foreign policy backed by a strong military. This environment helps explain why a woman who might two decades ago have been an occasional afternoon wide-show curiosity has emerged as an influential commentator on contemporary Japanese affairs.

Interview begins

Do you remember your grandfather?

My memories of him are slight. My grandfather became prime minister when I was just 2 years old. He was away most of the time during the following 3 years and 8 months. And at the end of the war, my family hid in Ito for 5 years and my grandfather was detained at Sugamo Prison. There were lots of people in the house: the driver and so on, so we seldom got time alone. During the war my mother used to bring me and my older brother Hidekatsu to the Prime Minister’s Residence every day where we were left to ourselves. Once in a while, we were able to eat with our grandfather in the residence, with an official cook and staff, but I can’t really remember his face. My brother remembers him. He used to sit on his knee. My grandfather used to feed him fruit. My brother said he was a really gentle person. He felt sorry for the children of the drivers and police because their fathers were so busy. He used to play with the children in the garden and bring them toys. When grandfather was in Sugamo my brother went to see him often. Grandfather worried terribly about my brother’s future, how he was going to suffer with that name. We suffered awful discrimination with our name. We weren’t allowed to sit in class. Even when we changed schools we weren’t allowed into the classroom. My little sister was beaten and came home covered in blood. My brother couldn’t go to school so he was taught by private tutors. That was what it was like at the end of the war in Japan. Iwanami was my real name. I didn’t start to use Tojo until quite recently. The name Tojo was untouchable for 50 years. What changed it was the film Pride.

Do you think Japanese schools should teach more about your grandfather?

I don’t think there is any particular need to teach about him as an individual. The Meiji Era was the first time that a small Asian country had made an impression on the West. It was a source of pride that in Scotland and Turkey and elsewhere they named streets and buildings after us. Japan should have pride in these things and they should be taught. We should properly explain the international situation at the time, and what the Tokyo Trials were all about. How terrible the situation was. We were surrounded and facing attack. We had no oil, or steel and all our assets abroad were seized. How were we to protect all those millions of Japanese except by standing up for ourselves? The media – the Asahi, Yomiuri, all of them were fanning the flames, saying “What is Tojo up to? Why doesn’t he fight back?” The media can’t say it was not involved. The people were also involved. Even fifth-grade elementary students were asking: what will we do without steel or oil? And now they talk about the Emperor’s responsibility. It is terribly saddening. The Japanese government is concealing all this. It’s not a question of respecting my grandfather. It’s about learning to respect someone who loved and fought for his country. Not just Tojo, but also the 2.6 million soldiers who died. We should respect those who fought for their country and that’s what should be taught in schools.

Some describe him as “an extreme nationalist and a fascist who hated the very notion of compromise with Britain and the U.S.”

People say lots of things. He loved his country.

You could make the same arguments for Hitler, though, couldn’t you? He loved his country too.

That’s different. He killed his own people – Jews.

Well, he did. But those who support him would say the same as you – that he loved Germany above all else. And in any case, ‘Jews were not real Germans.’

My grandfather didn’t kill his own people. A lot of people died as a result of a war that could not have been avoided. You have to properly understand the stance of each country. And therefore you need to teach why the countries went to war. We shouldn’t keep repeating that Japan was bad. That destroys pride in our country. I mean, if you join a company and are told that the boss is a bad guy and the company is evil you’ll stop wanting to work for that company. It’s the same.

Japan might not have killed Jews, but it is accused of massacring millions of Chinese.

That was in battle. Please don’t confuse the two. Do you know what benhei (soldiers masquerading as civilians) means? They are soldiers who hide among civilians and attack the Japanese army from behind. You can only tell once you capture them. Australians, British and Americans probably don’t know, but in what is referred to as the Nanjing Massacre there were many such people. Western journalists all believe this Nanjing Massacre. The Chinese say 300,000 were killed. There were media representatives from 150 countries. And as the army entered (she uses the word nyujyo here, which means to enter a city triumphantly) Nanjing and began their assault on the city’s castle these reporters were running alongside them. That’s how important the Japanese side thought this was. A safety area was set up with 200,000 under John Rabe and the International Committee for the Nanjing Safety Zone. So how could 300,000 people have been killed?

I’ve heard that argument many times before. The truth is nobody knows exactly how many people were there, but certainly the numbers were swelled by refugees from outside the city. We don’t have to get bogged down in figures to know that the army behaved brutally. There were many witnesses, including Rabe, who even as a Nazi was shocked at the behavior of the troops.

There was only one witness at the Tokyo trials who said he actually saw what had happened. The rest was complete rumor and hearsay (denbun bakkari).

Rabe was not the only witness. There were reporters there, including one from the New York Times, another from the Manchester Guardian, not to mention thousands of Chinese civilians.

The truth is coming out now. Fujioka-san (of the Society for History Textbook Reform) has researched this and shown one-by-one how the photographs of the incident were faked by the Chinese side.

I’m sure there is probably some faked evidence, but how can you only focus on the molehill of evidence that supports your claim and ignore the mountain that refutes it?

[Impatiently] Anyway, the truth doesn’t just come from one side. You have to look at what really happened from all sides because there is so much hearsay.

So do you think that China and Japan should cooperate to create history textbooks?

No, mutual understanding is impossible because each country’s stance (tachiba) is different. Even when the truth is the same, the interpretation by China and Japan is often completely the opposite. For example, for Koreans the man who assassinated Ito Hirobumi [1841-1909 – first Prime Minister and drafter of Meiji Constitution] An Chung-gun is a hero, but to us he is a criminal. That’s the kind of thing I mean. It’s completely impossible.

I’d like to ask you about Unit 731

[Tojo was commander of the Kempeitai of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria when Unit 731, charged with developing chemical and biological weapons, began experimenting with live victims. Tojo was allegedly a supporter of biological warfare and the work of Ishii Shiro, the chief medical scientist at 731] I know nothing about that or what went on in Manchuria. I’m not a historian. If you want to talk about Yasukuni or something like that, ask me. For anything else, ask a historian.

But you’ve heard of it?

I’ve seen the photos by China which look at ways of disinfecting against pests. I don’t know about it.

Why didn’t your grandfather kill himself by committing seppuku like other leaders?

You know how Mussolini died: being lynched and hung upside down in the streets? And Hitler’s death was tragic too. He wanted to avoid those kinds of deaths. And of course my grandfather knew his death would be broadcast all over the world. He didn’t want to shoot himself in the head because he didn’t want his face to be destroyed and sent all over the world. He would have died from the shooting wound to his heart, from bleeding, but he was saved by the Americans who wanted to put him on trial.

Do you resent America?

Not even a little. If I resented America I wouldn’t be happy that my daughter was married to a citizen of that country, would I? My grandfather admired America and said we could learn from it. And his American lawyers defended him and said the most amazing things. Other lawyers strongly criticize the actions of the Allied Forces. Those people treated my grandfather with great respect and he respected them, even as enemies.

Can I ask you about the Emperor? How do you feel about millions of people being trained to believe that it was noble and beautiful to die for the Emperor?

It wasn’t beautiful to die for the Emperor. People were trained from birth as Samurai, as soldiers. It was considered natural for millions of people to work and ensure that the emperor was not dishonored. This wasn’t for the Emperor; it was for the country — to protect the country. That was the belief: it was absolutely natural for people to take responsibility for protecting the country.

You don’t want to go back to that?

That was then, for better or worse, no matter how we look at it now. This is now. Japan has been at peace for 60 years.

Couldn’t war happen again, perhaps with China?

Of course not! The world wouldn’t accept this. If China tried to do something, Taiwan, America and other countries would become involved. The world would be looking on. There is no way Japan will become involved in a war with China. We are told we are not a military power even though we are an economic power, right? We don’t have an army, just defense forces, right? We have no nuclear weapons. The countries that have these things are America and China. We are not an aggressive (kogekiteki) country. When we did go to war, it was because it couldn’t have been avoided.

How about an attack by North Korea?

That is not a normal country. Who knows what it will do.

You don’t think there are a lot of similarities between N. Korea today and wartime Japan?

Absolutely not; please don’t make that comparison. That is an insult to those who died in the war.

Do you think the Emperor bore any responsibility for what happened?

None at all; his majesty wanted peace above all. (Heika wa akumademo heiwa wo motometeita ) . The emperor is a special existence (tokubetsu na sonzai). He is not little normal people. The Japanese Imperial Family is not like the English royal family. He was respected deeply by Japanese people who happily gave up their lives for him. People died saying: Long Live the Emperor! They didn’t shout: Long Live General Tojo! 2.6 million of these people are in Yasukuni and that’s why we should go there to pay our respects. I really want that with all my heart.

Your grandfather had no resentment against the emperor? He lived while many others were executed.

If there was no emperor there would be no Japan. My grandfather and others died to protect the Emperor, to protect Japan. That was perfectly natural. We can’t even talk about those beliefs today. The idea that he is a symbol of Japan as we have been taught in the postwar period is insulting to the emperor. He is the essence of Japan (kokka genshi). He is nothing at all like a US president. He is Japan.

But the Emperor himself admits he is Korean.

I know nothing about his roots, but I was astonished that he said such a thing. His majesty (it is clear here that heika refers throughout to the Showa Emperor, not the current occupier of the Chrysanthemum Throne) would never have said such a thing. He knew the limits of what to say. The current Crown Prince (Naruhito) chatters away about everything. As the national essence (kokka genshi) he has to know what to say. He has to maintain the dignity [igen] of the Imperial Family.

The emperor also seems ambiguous about the flag and anthem issue.

What country doesn’t have a flag and anthem? Why does only Japan have to endure this stupid criticism?

What are your feelings about Yasukuni? About your grandfather’s secret enshrinement there?

The prime minister promised to visit on Aug. 15 and he should. He should ignore pressure from China and other countries. This is a domestic affair.

China has the right to protest though doesn’t it? Japan invaded their country and killed millions.

China played no part in the San Francisco Treaty. Countries that were not involved in the treaty or the Tokyo Trials have no right to talk about war criminals now. So why is China complaining now? The Japanese fought the Nationalists (KMT) not the Communists. It is now a completely different country. China and Japan later signed a treaty and war criminals and prisoners were released. The word war criminal (senpan) does not exist in that treaty. They should abide by that treaty. It is unforgivable (zettai yurusanai) that they continue to interfere in our domestic affairs.

Do you feel that Japan should not recognize the results of the Tokyo Trials?

On May 3, 1952, MacArthur said Japan fought a war of defense. Japan had no choice. It had no resources, he said. My grandfather said the same. Despite this, our own government can’t say the same. It is very odd. MacArthur said it wasn’t a war of aggression but now Chinese people who weren’t even there can call it a war of aggression.

So it was a war for resources?

No. We were standing up for ourselves. Every country accepts the notion of self-defense.

Is this why your grandfather referred to himself as a “war responsible person” but not a “war criminal”?

Yes. He behaved like a samurai, and took responsibility for his failures as a good soldier. But by what definition was he a criminal?

Notes

[1] Onoda returned to Japan in 1974 after 29 years on the Philippine island of Lubang, where he fought as an army lieutenant. He was apparently unaware that World War II had ended. He was later pardoned by the Philippine government for killing at least 30 Filipinos and wounding about 100 others during peacetime.

[2] Tojo also criticized Ishihara Shintaro in a September interview on the right-wing Sakura TV channel after the Tokyo governor said that Tojo was not worthy to be worshipped as a god at Yasukuni because he had only used a 22-caliber weapon in his attempted suicide. See: http://www.ch-sakura.jp/onlinetv_sakura.php

[3] Of General Tojo’s children, daughter Makie (nee Tamura) seems to have lived the most anonymous life. Her late husband, Major Koga, was one of the conspirators who tried to stop the Showa Emperor’s surrender on Aug. 15, 1945. She remarried and became a case worker in the National Mental Health Research Institute.

[4] In an interview with Fuji Television on June 5, 2005, Tojo said her family reacted ‘coldly’ to the publication of the books. “I explained that I was not speaking as a member of the Tojo family but as an individual,” she said. The decision ended her relationship with her uncle Tojo Teruo.

Many thanks to Amakasu Tomoko for her help in researching this article.

David McNeill is a Tokyo-based journalist who teaches at Sophia University. A Japan Focus coordinator, he is a regular contributor to the London Independent and a columnist for OhMy News. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted November 10, 2005.