Introduction

Masako Robbins’ intimate personal account of her life in pre-war, wartime, and early postwar Okinawa compels the reader to experience the history of this tumultuous era from the perspective of the daughter in an impoverished family. Sold as a child by her father to a brothel in the 1930s, and drafted by the Japanese military as a combat nurse during the Battle of Okinawa, she barely survived after being trapped in a cave collapsed by shelling. Placed in a refugee camp at the end of the battle, her family later returned to their village to find their home destroyed. Her strength, resourcefulness, and resilience throughout these horrifying ordeals are nothing short of astounding. Now eighty-six years old and living in Yuma, Arizona, Masako learned enough English after coming with her first husband to the United States in 1952 to write this memoir in English. In 1964 she met Warren and Mieko Rucker who, together with Karen King, edited the text, a portion of which is presented below.

*****

In the beginning I was Shinjo Masako. My parents were from Okinawa though I was born in Osaka, Japan, in 1928. My father was a factory worker in Osaka before he took the family back to Okinawa. Then, when I was not yet of school age, my father sold me to a house of prostitution. Ironically, the horror of the Battle for Okinawa eventually led to a very different life for me. After the battle, I worked for the U.S. military, earning enough money to buy my freedom from the brothel. I also met the American who became my first husband. Years later, in the United States, I sold my paintings and taught art for a number of years at a college in Arizona. This is my story.

————————————————————————————-

Poverty

My older brother and sister, Motoichi and Hanako, as well as my younger brother, Akio, and I lived with our parents in Osaka, but I have few memories of life there. I do recall going to the train station to meet my father when he returned from work bringing candy for us. And I remember the death of my sister, Hanako, who was sickly and huddled by the warmth of the hibachi. I don’t know when she was born or why she died, but I can still see the funeral car that took her away while I stood by the door watching it leave.

Next I remember being on a ship. We were in the hold of the ship, and we slept on the floor with other people around. I was told not to go up the stairs but did not know why. When the ship docked, I did go up and I saw a big mountain. Later I was told that the ship had stopped in Kagoshima on the way to Okinawa, but I only remember standing there gazing at the mountain.

What I remember next is a rainy night. I was so cold that I was crying. We were waiting for a bus to take us to my father’s home village, Imadomari, in Nakijin, Okinawa. Our house had a thatched roof. Part of the floor was wood and part was dirt. We didn’t have enough food and I was hungry all the time. Mostly, I think, we had sweet potatoes and clear soup.

My head had scabs, and there were lice and flies in my hair. I remember Mother putting a towel over my head. Maybe that was to protect my little brother when I carried him on my back. Mother also poured petroleum oil over my head to kill the lice.

Three girls who lived nearby were my friends. One was named Katsuko, and her father was the school principal. Their house had a red tile roof and was surrounded by a rock wall. At times, Katsuko invited me to her house, but when I saw her father I was so frightened of this very important man that I would leave.

We were so poor that we didn’t have a decent door to close when we all went to bed, and there was nothing to keep us warm but thin futons which we shared as the wind howled outside. Sometimes I was awakened by a rat biting my finger. Throughout the day, we could hear rats moving in the ceiling beneath the thatched roof.

At night, we had a dim oil lamp. I was always pleased when there was moonlight because then it was brighter outside than it was inside our house. Even today I still love moonlight. It seemed that every night my father drank sake, and sometimes he would argue loudly, about the property line, with the man who lived in the house behind ours. We children were so upset that we couldn’t go to sleep until our father finally came inside and fell asleep. The only good thing about living in Imadomari was that my favorite playground was the nearby shore of the beautiful sea.

One day my father said that soon I would go to Naha, the capital of Okinawa. I remember having heard good things about Naha so I must have been very excited, not knowing the change that was to come in my life. That evening my friend Katsuko brought sugar water that she and two other friends and I shared. They were a few years older than I and probably knew what was in store for me. The four of us took turns sipping the sugar water, a delicious treat for me because my family could not afford such a special luxury.

|

Naha before World War II |

The following day I wore a pretty kimono and rode with my father in a taxi to Naha. We went into a huge house called Namimatsu-Ro where a lady welcomed us and led the way into a large room. In the house there were many ladies, and someone brought tea for my father and candy for me.

The next morning, my father, an older woman, and I went to Nishinjo, a big intersection. My father got into a taxi and I too tried to get in. He stopped me, saying that I had to stay here and that I would have good food and wear pretty kimonos. Then he left. I tried to catch up with my father’s taxi but could not, so I just stood there crying. I didn’t understand what was happening and was scared. The strange woman standing beside me held me tightly so I would not run away.

I remember crying for the next few days and sitting in a corner. Everyone tried to be nice to me, but I was confused and didn’t know why my father had left me. I didn’t understand that this was my new home and that in the coming years I would be trained in music and traditional Okinawan dance, in entertaining, and finally, when I was a teenager, in serving men.

A House is Not a Home

The lady who had bought me was originally from the same village as my parents. I called her Anmaa, meaning mother. She was one of four older women in this eighteen-room house, each of whom had three or four girls. Anmaa had three teenaged girls in addition to me, and she also had overall responsibility for the house. She collected rent from the three other women and, in turn, paid the house owner. The house was in Naha’s entertainment area known in Japanese as Tsuji (Okinawan Chi-ji). Within Tsuji was a licensed “red light” district, or Yukaku.

|

Annual Parade of Tsuji courtesans before World War II |

My formal music and dance training began when I was six or seven. I took lessons in Okinawan dance from Mr. Arakaki and music lessons on the thirteen-stringed koto from Mr. Matayoshi. We called the dance teacher Arakaki-Tari and the music teacher Matayoshi-Tari an honorific showing respect. Arakaki-Tari was quiet and easygoing when I made mistakes in dancing. Matayoshi-Tari, on the other hand, was intimidating because if I made a mistake with my music he would bang on the koto and yell. If I played without a mistake, however, he would smile and sometimes reward me with candy or hot tea. After Matayoshi-Tari’s students mastered our music lessons, he would have us perform at various functions, and I felt honored at those times.

When I was perhaps eight or nine years old, Anmaa took me and my three sisters to Imadomari, her home village and mine, for a few days. My mother came to the house of Anmaa’s brother where we were staying and asked if I might be allowed to visit my parents’ home. Anmaa told me to go with my mother. I had not seen my parents for four or more years, and this woman did not seem like my mother. I could not even remember her face. However, Anmaa told me to go. When we got to the house, my father, two brothers, an old woman, and other people were waiting. I later learned that the old woman was my grandmother and the other people were my relatives.

I didn’t want to spend the night with them, and I went back to the house of Anmaa’s brother. She asked me what had happened, and I told her the place was poor so I had left. She told me to go back and stay with them. I obeyed her of course. When everyone saw me return, they cried. I cried with them. I felt sorry that they had to live in such a pitiful place. While I was there, I learned why my father had sold me. He had a bad leg and was unable to work. In addition, my younger brother was very sick. Several days later, Anmaa, my sisters, and I returned to Naha.

Many of the memories of my childhood are lacking chronology or sequence. I can’t be sure just how old I was when a thing happened or, in some cases, if one particular thing happened before or after another thing. When I was about six or seven, I started school. I loved going to school, but I was able to go for only two or three years. After that I had no further formal education.

My dropping out of school resulted from the harassment of an older sister, Kami-Chan-Nesan. She hated school. Also, she probably was jealous of me because Anmaa spoiled me. I was younger and, unlike my older sisters, had few required tasks beyond my music and dancing lessons. Kami-Chan-Nesan would force me to skip school with her. She would make me walk with her to the Naminoue shrine and we would sit together in the park. With nothing to do, I’d sometimes pass the time by catching a green beetle, attaching a string, and flying it around in circles. When we went home, I would have to give the impression that we had been in school all day.

Finally, the teacher came to talk with Anmaa about my absences. When Anmaa asked me why I had not been going to school, I had to lie because I feared that Kami-Chan Nesan would beat me. From my answers, Anmaa felt that I just didn’t like school, so she told me not to go anymore. By then, I was so far behind in my work that catching up would have been difficult anyway. The only unpleasant thing about my actually going to school had been that the students and townspeople looked down on anyone who came from Tsuji. Some girls in class had pretty dresses and shoes but I didn’t have any nice clothes and was embarrassed. I did have pretty kimonos, but I could not wear those to school.

I don’t know how old I was when I became very sick with pneumonia. I had a high fever and eventually drifted into unconsciousness. Fortunately, a patron of Anmaa’s was Doctor Nakamoto. He was the doctor at the penitentiary and had a small medical office near his home. I had run errands there for Anmaa and sometimes played there with his nurses. Also, my sisters went there once a year and cleaned the house from top to bottom. I later learned that when I was sick the doctor had visited me twice a day. If I had been at the home of my poor parents and not had Anmaa’s access to Doctor Nakamoto, I might well have died. When eventually I did regain consciousness, my father was sitting beside me. Anmaa, thinking I might die, had sent word for him to come.

During the years I stayed in Tsuji, there were many vendors who went door to door. Women, for example, carried on their heads a variety of things for sale, and men balanced on their shoulders a pole holding such things as two wooden water buckets. I especially remember a blind masseur who in the evening played a flute to announce his approach. When I was about nine, Anmaa had begun having me massage her several times a week. Usually she went to bed around eleven o’clock and then I would have to massage her for an hour. This was one of my duties even though I was tired and could hardly stay awake. The blind masseur came at an earlier hour, and on those nights when his flute could be heard in the street, Anmaa would send me out to fetch him. Then I was free, unless my elder sisters needed me for something, and could go upstairs to the end of the hall and sleep.

Yoshiko-Nesan, one of Anmaa’s older girls, loved foreign movies and she sometimes took me with her to see one. I can remember movies starring Shirley Temple and Charlie Chaplin. Yoshiko-Nesan was intelligent and was kind to me. In return, I admired her greatly. I have other good memories of my childhood in Tsuji. We children often played on the tops of tombs in a large cemetery nearby. This cemetery also was the place where, on the evening of the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month, neighborhood people would gather for moon-viewing parties, or juguya in Okinawan. These parties atop the tombs were like picnics at which we ate delicacies prepared by my older sisters and viewed the beautiful full moon.

I must have been around nine or ten years old when Anmaa took all of her girls back to her home village (and mine) at the time of her niece’s wedding. My older sisters were expert in cooking and spent two days preparing food for the wedding party. The house was not large enough to seat all of the guests, so straw mats were spread in the yard in front of the house. It was my job to clean the yard and get it ready for the expected overflow of people. While I was cleaning the yard, I saw Akio, my young brother, watching me from between the trees. He looked pale and hungry, and I knew that he and my real family seldom had enough food in their house for him and the others. I went into the kitchen and brought him a fried, round pastry that we Okinawans call tempura. His wide smile confirmed that poor Akio rarely had such a treat. Afterwards, he came time and again and stood between the trees waiting expectantly for the food that I’d sneak for him.

Following her niece’s wedding, when Anmaa, my sisters, and I returned to Tsuji, the area around Naha became hectic with military activity. We saw more soldiers, and able-bodied people were required to help them. We children were happy because we got to ride on a truck every day to help with road construction. Our job was to carry baskets of small stones to fill the road surface. Many women busied themselves making hara-maki, cloth bands to be worn around the waist by soldiers going into battle. When one thousand stitches had been made, these were called sannin-bari and were believed to keep the wearer safe. This must have been when Japanese soldiers were fighting in China but before the war in the Pacific began.

In the years leading up to World War II, I was still living the life of a child. For New Year’s festivities, Yoshiko Nesan would dress me in a pretty silk kimono and with other children I would go around to receive money or gifts. Some of the money I always saved to give to my father when I saw him. After Anmaa’s sister died, she took my sisters and me back to Imadomari for Obon, the five-day celebration honoring the dead. First came a trip to the family tomb for cleaning the area plus leaving flowers and offerings of food and drink. Then we prayed and invited the family spirits to return home for their annual Obon visit where similar offerings to them were placed on the family altar, and incense was burned. People would parade in the streets or road and there would be folk dancing and drama. At times I joined in the dancing. Above all, during the five days of Obon there was food preparation and everyone shared. In addition, gifts were exchanged. On the last day, paper representing money was burned for the use of the deceased as they returned to the spirit world, and finally the family spirits departed.

When I was fourteen, I began to menstruate. I had no idea what was happening. No one had prepared me for this. I turned to my closest friend, Kikuko. We lived in the same house, but she belonged to another woman. Kikuko was a bit older than me and seemed to know everything, so when I had questions I usually asked her. Since the time that Anmaa had bought me ten years before, I had been an expense to her. Now I was approaching the age at which her investment would begin to pay.

By the time I was fifteen, Anmaa, had prepared two rooms for me. On one wall was a gold-colored screen and at its center a Sansui landscape of mountain-and-water. A room divider was made of beautiful gold-papered sliding doors. There were glass doors on the corridor and wooden outside doors to protect against intruders and rain or storms. And Anmaa must have spent a small fortune on the furniture, bedding, and kimonos for my coming of age. It seemed that my life of misery was about to start.

Fortunately for me, however, Anmaa was selected for an honor which was to occupy her for some time and delay the beginning of her profiting from me. Each year, the most important women in the yukaku, the licensed red-light district of Tsuji, chose two houses to keep and maintain the district’s two traditional icons or “business gods”. In 1943, Anmaa was chosen for the important responsibility of caring for Shi-Shi, the lion god. It was my job to dust Shi-Shi’s altar each morning and place fresh salt. Then I put tea and hot rice on the altar before anyone in the house could eat. Once a month, the yukaku’s important women met at our house. My older sisters prepared fine meals to be served in the room reserved for the altar and the meetings. Because this was the room which Anmaa had prepared for me, I would not receive a man for another year.

Each year Tsuji had a celebration and parade. In 1943, because of Anmaa’s responsibility for the lion god, I was the “princess” of the parade. Dressed in a beautiful kimono and with an elaborate hairdo, I rode in a rickshaw. Many girls in colorful kimonos walked in the parade, and they had wooden horses in front of them. This was called juri-uma, and I believe it continues even today in Tsuji’s traditional annual parade. Those in today’s parades, of course, are not prostitutes.

No Longer a Child

That remarkable year came too soon to an end, and now I was sixteen. One day, Anmaa called me in. As I sat in front of her, she told me that an Okinawan man who had lived in Hawaii wanted me for the ritual misuage, meaning that he would pay well for my virginity. I was horrified and begged her to wait because I was still too young. She became very angry and told me that my misuage should have taken place before now if she had not had the Shi-Shi obligation. I cried and was so scared that I ran out of the room. I tried to go upstairs, but Anmaa caught me, pulled my hair, and dragged me back to her room. She began beating me as I had never been beaten before. She asked why I thought she had spent so much money raising me and said it was not so that I could have a good life, but so that when I got to the right age I could make money for her. Even today, as I write this I am overcome with sadness.

She went on and on. Again I tried to run away upstairs, and again she caught me and dragged me by the hair back to her room and resumed the beating. I had heard from my older sisters that Anmaa used to beat them, but nothing they described was like this. I felt like a mouse being attacked by a snake and finally surrendered. She then told me that the man would come back tonight and he wanted me. Having lived and worked in Hawaii, he had enough money to pay the high price Anmaa demanded. She made me sit in her room all afternoon. When night came, I had no choice but to do as Anmaa had ordered. My older sister, Yoshiko-Nesan, prepared me and told me what to do. I don’t know who laid out my bedding and put the mosquito net in place. I was crying the whole time.

The man who had returned from Hawaii pulled me inside the mosquito net. I think he told me not to worry, that he was not going to hurt me. I don’t have any clear memory of what happened after that, and I can’t remember what he looked like. I was crying and I hated my father for having caused me this torment. I remembered a lovely pregnant woman who had visited me here in Tsuji when I was perhaps six or seven. Anmaa had told me that this woman was my real sister who had come from Osaka to have her baby in her husband’s home village on Okinawa. Until then I hadn’t known that I had an older sister, but now I envied her and the happy, married life she was living.

The night ended. Nothing more went on for a few weeks. I thought that it was over, but then it happened again. I do remember this man. He was short and very dirty looking. He smelled so bad that I was sickened. I was miserable and lay there waiting for him to finish. Then I got up and ran to the kitchen where we could pump water from the well. I pumped a bucketful and washed all over. Still I felt dirty. Later, I’m not sure how long a time it was, I began to itch. I didn’t know what to do, so again I went to Yoshiko-Nesan. She recognized the problem immediately and gave me some powder. I applied it as she directed. Though the powder eventually solved the itching problem, I was furious with Anmaa and thought that I would not let her keep doing this to me. All she wanted was money. I would find a way to earn money and buy my freedom from this place as soon as I could.

In an attempt to prevent more such horrible experiences, I took every opportunity I could to entertain simply by singing and dancing. One day I was hired to entertain and serve sake at the Hugetsu Tea House. This was a beautiful tea house near Naha Port and its clients were important people. Not many girls were selected to go there, so I felt very lucky to have been chosen. The owners were a Japanese man and his wife, a former geisha. They had two lovely geisha women, and it was my job several times a week to help them serve food and sake. Many of the men who came to the tea house were Japanese government officials. This paid well, so Anmaa didn’t complain too much. One of the government officials who was very kind to me, and was to be extremely important in my life as the Battle of Okinawa drew nearer, was Mr. Sato. I think that he was one of the very top men among the Japanese government officials on Okinawa. Soon some of the men that I served tea and food or entertained at the Hugetsu Tea House began to hold small parties in the rooms that Anmaa had decorated and furnished for me. This paid well. I wasn’t expected to sleep with the men. Serving drinks, entertaining, and cleaning up afterwards was hard work and time consuming. Anmaa complained though that I was a fool because instead of simply taking a man I let a group stamp around and make a mess, but I didn’t mind. As long as I was giving Anmaa money, she didn’t force me to do more.

I was working several times a week at the Tea House. One night there was a banquet given by government officials, and they invited Japanese Navy officers. I was busy serving Mr. Sato and others without paying much attention to who else was there. It turned out, however, that in the group was the man who would be my first love. It was Lieutenant Inoue, a young navy medical officer.

A few nights later, he and five other navy officers came to my house for a small party. I ordered food and sake for them and asked Ha-Chan, a pretty girl who was younger than I was, to help me serve and entertain. The officers had a good time, but finally they left…all except for Lt. Inoue. I hoped he would leave soon, but he did not, so I asked Ha-Chan to stay with me. About two-o’clock, Ha-Chan said she was sleepy and left. Lt. Inoue still didn’t leave. I prepared a bed for him to sleep on the tatami. I lay there very still, but he didn’t touch me, for which I was grateful. Later I followed him to the entrance to open the door and let him out. He told me goodbye, but he didn’t leave me any money. I was worried, because I knew Anmaa would be angry. When I went back to my room and began cleaning up, I saw one-hundred yen on the table. I was completely surprised, and thankful. What a relief! One-hundred yen was a generous sum of money in those days. When I gave the money to Anmaa, she smiled widely and, holding the money, moved her hands up and down almost as if giving prayerful thanks.

Two days later Lt. Inoue returned alone. He was gentlemanly and treated me kindly. After that he came almost every other day. One night, Mr. Sato and a few other officials were having a small party in my room and, though I wasn’t expecting Lt. Inoue, he arrived. He waited a long while in Anmaa’s room and was very displeased. But he was not my patron, and the small parties in my room satisfied Anmaa and kept her from bringing a man to me. After that, Lt. Inoue came almost every night. He provided enough money that Anmaa didn’t complain. More important, he had brought happiness to my life. Not yet seventeen, I was in love. One night he took me to a movie. I was so shy that I walked behind him and didn’t sit close to him. Another night, however, he came with bad news, saying that he was being transferred to Saigon. I was crushed and cried. Before he left, he provided enough money so I wouldn’t have to worry that Anmaa would bring another man to my room.

A month after Inoue-san left for Saigon, I received a letter from him and a beautiful alligator purse. It was the finest gift I had ever received and was my special treasure. Within a year, during the battle of Okinawa, I lost it along with almost everything else except the clothes I had worn for months.

A few months after I received the letter and purse, Ha-Chan and I went to a movie. About this time, nightly blackouts began, so this must have been our last movie. When we arrived home, someone said that Inoue-san was waiting. I rushed to my room and into his arms. He had been promoted. Now he was stopping overnight in Okinawa on the way to Taiwan. He had visited his parents in Japan and had told his father about me. His father forbade him to marry me, but Inoue-san said that because he was the second son he could marry as he wished. He intended to call me to Taiwan to be with him. He had brought a box meal for us to eat together as we listened to phonograph records. Music was forbidden as were lights, so we listened to classical western music in the dark with a blanket over the phonograph and our heads. Years later, I recognized Schumann’s Traumerei as the one that had been our favorite. The next morning Inoue-san left for Taiwan. I never saw him again.

Shortly after that, conditions on Okinawa worsened. The military was now openly in control. Our kimonos had to be converted into mompe, pajama-appearing pants that were tied at the ankles. Any food that was available was rationed. Japanese soldiers came and took chairs and tables. They also took jewelry and other things of value, especially gold and silver. Anmaa had to give them her two large gold rings. Some of these soldiers were kempei-tai, military secret police. They were very harsh, and all of us feared them as they went from house to house demanding things.

Then we heard that many girls and young women would be sent to live with the Army. This was frightening because we did not know what would happen to us. Neither we nor Anmaa had any choice. We simply had to do as the army demanded. The unit that girls from my district would be assigned to was part of a larger force that had come from China and was commanded by Colonel Ueno. I was called to the home of the Colonel’s mistress, who turned out to be the biological sister of my favorite older sister, Yoshiko. Recently Yoshiko had been able to buy her freedom from Anmaa. When I arrived at the home of Colonel Ueno’s mistress, Masako-Nesan, she introduced me to the Colonel and one of his lieutenants. The Colonel was a short, stocky man. He told me that soon I would go with him and his unit to entertain officers. Frightened, I bowed and left.

The following day I received a message telling me to go to the house of Mr. Sato, the important civilian official who had always treated me in an almost fatherly way. Mr. Sato told me that he had personally asked Colonel Ueno to see to my welfare and that was why the Colonel and his mistress had called for me the previous night. Mr. Sato said that some other girls and I would have to move to another part of the island with the Colonel’s soldiers, but that I shouldn’t worry because the Colonel had assured him that I would not be harmed. As I left, Mr. Sato gave me a roll of kimono material. I took the material to Yoshiko, who, now free of Anmaa, had a place of her own, and asked her to make me a kimono.

No one knew how long the military control would last, but at least Anmaa was no longer in charge of my sisters and me. As might be expected, her attitude toward us was very unpleasant. While experiencing a sense of freedom, there was sadness in preparing to move with Colonel Undo’s unit to Urasoe Village. I could take only a few things and didn’t know what would happen to the others that I had to leave behind. As I held the phonograph record that Inoue-san and I had listened to, I was so sad and lonely that I began crying. I remembered the night that I walked behind him on the way to the theater and then, once inside, sat away from him. I wanted so much to have that night to live once more and do differently. I wondered when I would see him again.

My “Military Duty”

Many other young girls and I were loaded on a truck to leave for Urasoe Village, a place unknown to us. I felt at that time much as I had when, as a small girl, I was being taken from my home in Osaka to an unknown destination in Imadomari. Urasoe was a farming village in a rural area, and there was not much to see until we reached the place we were to stay. There was one large building with many rooms and nearby a smaller building with one room in front and two behind. I was given the front room of the smaller building. Colonel Ueno and his mistress had the two back rooms. The unfortunate girls who had come with me on the truck from Tsuji were all assigned to the large building with its many rooms. In the days to come, from my room I would see soldiers lining up at the large building, each waiting with a number for his brief time with one of the girls.

On the day we arrived in Urasoe Village, Colonel Ueno’s mistress called me into her room. There, the Colonel asked me if I needed anything, and when I replied that I did not, he asked if everything was all right. I answered that everything was fine. He told me not to worry and to let him know if I needed anything. I began to understand how extremely fortunate I was that Mr. Sato was a powerful civilian official and that he had personally asked Colonel Ueno to see to my welfare. In addition, it was my good luck that the Colonel’s mistress was the biological sister of my favorite older sister in Anmaa’s house.

When we had been in Urasoe Village a few weeks, Mr. Sato came to see Colonel Ueno. While he was there, he called me in. He said that he was pleased to see that I was doing well. Mr. Sato looked exhausted, probably from hectic preparations as the war came closer and closer to Okinawa. After he left, I never saw him again, but I feel in debt to this day for his kindness to me. From time to time, I was called on to dance and serve at officers’ parties or gatherings in the Urasoe area. Life with the military was miserable for us, but by having to entertain only the officers, in many ways I personally had more freedom here than I had at Anmaa’s. Though there was nothing to see or do in Urasoe, we occasionally walked about and the local people treated us with contempt.

One day, hearing the sound of many airplanes, we went outside to watch. High overhead were beautiful silver planes, and we were excited to see them. We raised our hands and shouted banzai. Nearby soldiers yelled at us that those were enemy planes and for us to get in the shelter. They bombed Naha, and after dark the sky was red as the city burned. Later, evacuees walking from Naha began coming our way. Some carried nothing. They said that the bombing was so intense that they were lucky to have escaped with their lives. Among them was Anmaa. She looked weak and helpless, having lost everything. She stayed in Urasoe Village, but now she had no power over me. Like all of us, she was under military control. Among the evacuees who came from Naha with Anmaa were Ha-Chan and Yoshiko-Nesan. Ha-Chan was a pretty girl two or three years younger than I and was like a real little sister to me. She was excellent at traditional dancing and joined me in entertaining officers until we later were moved from Urasoe to Shuri. As I mentioned earlier, before leaving Tsuji, I had taken to Yoshiko-Nesan my gift from Mr. Sato for her to make into a kimono. She apologized now for having lost it to the bombing and fire. As precious as it was, the kimono material seemed a small loss compared to the survival of Yoshiko-Nesan and Ha-chan.

Later, Anmaa went north to Imadomari where she stayed with her brother throughout the coming battle. At the same time, Colonel Ueno’s unit moved to Shuri. His mistress, Masako-Nesan, and we girls moved with them. We were in a large house, Masako-Nesan’s room in the back with my small room next to hers and away from the other girls. Colonel Ueno was true to his word to Mr. Sato that he would take good care of me. The other unfortunate girls, however, still had to service the soldiers who stood in line waiting their turn. I was called less frequently to entertain the officers with music and dancing.

Before long, Masako-Nesan said that Colonel Ueno wanted to talk with me and the rest of the girls. He told us that the enemy would begin the battle soon and all of us would be moving into a shelter with the military. The girls would no longer be required to service soldiers but would be trained as nurses’ helpers. After learning about tending to the sick and how to bandage and care for the wounded, we were given bags which contained first-aid items.

At this time we moved into the shelter underneath Shuri Castle, home of the royal court during the five centuries of the Ryukyu Kingdom that Japan abolished in 1879 and annexed as Okinawa Prefecture. It had become headquarters of the 24th Army, the main Japanese fighting force in the Battle of Okinawa. The size of the shelter was overwhelming. I could hardly believe my eyes. The corridors, lighted by electricity, seemed to go on forever. There were many rooms off the main corridors, and more corridors leading to more rooms. There was much confusion as we were moving in. Soldiers were carrying things this way and that, and we were trying to stay out of their way. There was a large kitchen with a storeroom loaded with food and many sacks of rice. All of the girls were assigned to one large room where we were to stay and sleep. Inside our room we had no water for bathing and no toilet, so at night we would go outside to look for some way to wash and for a dark place to relieve ourselves. When we were outside, we could hear bombing and gunfire and we could see distant fires.

Everyone was assigned duties, and I was responsible for taking meals to Colonel Ueno and some other officers. Masako-Nesan was still with him. He now looked haggard, but he inquired about my treatment and cautioned me to remain patient because things would soon be better. One day, while I was making my way along a corridor, I met maybe half-a-dozen soldiers leading a blindfolded man who was bent over and had his hands tied behind him. As I squeezed against the wall to let them pass, I saw that the man with the blindfold had red hair. Later I was told that he was an American pilot who had been captured.

There was a very young teenaged girl in our group in the shelter, and a lieutenant was using her as he wanted. I talked with her and advised her that she was too young and should stop seeing the lieutenant. She told him what I had said. Later, he called me to a remote place in one of the tunnels. He put a pistol against me and said that if I continued advising the girl he would kill me. I was so scared that I bowed with my head against the floor of the tunnel as I apologized. After that, I never told her anything.

Jigoku

We girls knew that the battle was raging beyond the relative safety of our tunnel shelter, but we had no real understanding of where the enemy troops were or what the Japanese Army was doing. The sounds of gunfire continued, as did the bombing. When orders came that we must leave the tunnel and make our way southward toward Itoman, we departed much as sheep to the slaughter. The following weeks, with much of the time being spent underground, might best be described by the Japanese word jigoku, which translates roughly as “hell.”

We moved out at night, in the rain. With no idea of direction or distance, we simply tried, in the darkness, to follow the moving mass of soldiers and civilians. Mostly, we used the main road only at night. The paths and roads were quagmires of mud. Beside the road were bodies of the dead, wounded, and others who were just too exhausted to go farther. At one point I saw a dead woman with her baby, still alive, strapped to her back. I made a move to help, but a soldier ordered all of us to keep going. When we finally reached Itoman, there was hot food, but I was so exhausted that I just wanted to sleep.

Soon we had to resume our march, not knowing where or how far we were going. In the daylight, whenever we heard an airplane we ran and lay down in the roadside ditch pretending to be dead. At last we reached Komesu village, and our shelter was nearby, deep inside a cliff. We were away from the military headquarters, but there were radio communication soldiers above us and other soldiers near the front of our shelter. Now there were only nineteen of us girls left.

Our shelter space was knee-deep in water. We had little food, no change of clothes, and no water to drink except for a small pond not far from the shelter entrance. We used that water for washing our hands and feet as well as for drinking. The local people had a few big urns of black cane sugar which they shared, but it lasted only a short while. I was the hancho, or leader, of the girls and assigned them their tasks, the main one being nightly forays into the surrounding fields in search of food. The bombing and gunfire kept us inside the shelter during the day. As night approached, however, enemy activity subsided, and we would venture outside in the darkness. I don’t know where the soldiers went or what they did, but we girls would scour the area for anything to eat. We depended most on finding sweet potatoes, a few of them having escaped the villagers’ harvest or our previous searches.

Early one evening, I had assigned the girls’ tasks and we were waiting for darkness in order to venture outside. Then there was a deafening explosion at the mouth of the cave. I could still see light outside, so I knew that the entrance was not sealed. But shortly afterwards there was a second explosion, then total darkness. Without light, we tried to gather our things and move farther back in the cave. There was a third explosion followed by screaming and moaning which lasted only a short while. Of the nineteen girls, only eight of us were alive. We had been fortunate enough to have been deep inside the cave, but now it seemed as if we were entombed by the collapsed walls between us and the entrance.

Some of us began to get sick from toxic fumes. We had been told to wear gas masks at times like this, but we had none. With towels dipped into the water we had been sleeping in, we covered our faces, which reduced the fumes we were breathing. When a girl seemed to be dozing off, others would keep her awake. Some soldiers had also escaped when the tunnel collapsed, and they had flashlights. When I asked them to try to dig us out, they said they had nothing to dig with. I told them they at least had their helmets and bayonets. Finally several began digging, and we all took turns. From time to time, someone would stop digging, saying that there was no hope, but others would not give up. A number of times, a soldier digging would mistakenly think he had broken through and yell back to the rest of us. There would be momentary elation followed once again by despair.

Ha-Chan began falling asleep, so I poured water on her and slapped her face. I was afraid that she was going to die. The soldiers who were digging kept telling us that there was no hope, but I encouraged them and they continued. After many hours, one soldier pushed his bayonet through and someone on the other side took it. When we heard that we cried with joy. One-by-one we crawled through the debris and reached the fresh air. It was now the middle of the night and we had been trapped for nine or ten hours. Outside, bodies of the dead were stacked up on both sides of the cave entrance. I collapsed.

Once again we moved to another shelter. This time close to the Headquarters where there were many officers. Now we were near Colonel Ueno and Masako-Nesan. Our new shelter was a cave with a narrow entrance and a steep descent into darkness. Strangely, I can’t remember being hungry during this period, but the other girls and I were always thirsty. We took turns holding a canteen as we tried to catch water dripping from a crack in the rocks, enough to wet our mouths but seldom enough to drink. We did this during the day, and at night we went outside and scavenged for food for the soldiers and ourselves. As we wandered the fields, shells fired from ships offshore often passed overhead, fireballs in the darkness. One night, the soldiers from our shelter went out, but only a few returned. Without being told, we knew what must have happened. A few nights later a bomb fell close to our shelter, wounding a soldier who was outside. He was at the bottom of the bomb crater, with a severe leg wound, and called for water. The other soldiers ignored him. The crater was so deep that we couldn’t help him, and we had no water. We were becoming so accustomed to the bombing and the gunfire from offshore that occasionally we ventured outside during daylight hours. The American ships were so close that, as we lay on the ground watching, we could see sailors moving about on deck, or in the distance a kamikaze attack.

One day three girls that we didn’t know came into our shelter and asked if they could stay with us. They had no other place to go. In their previous shelter, they said, there was a woman with a baby that cried constantly. The soldiers had sent the woman out for water and, while she was gone, the soldiers killed the baby. Another story described the cruelty of Japanese soldiers in dealing with Okinawans. Some soldiers went into an Okinawan house and demanded food. The mother told them that there was no food. The soldiers searched and, when they found that she had hidden a cup of rice, they killed the whole family.

During this particular time in the caves, we girls were fortunate in that the Japanese soldiers did not rape us. Of course, we had not had a bath or a change of clothes for months, we had slept in water on cave floors, walked on roads ankle-deep in mire, and on our knees had dug with our hands for food in darkened, muddy fields. There was almost nothing to eat and little water. We experienced constant confusion, fear, and exhaustion. I did not have a period for months.

The days and weeks passed in one seemingly endless nightmare. Now, more than half a century later, many memories of those horrible days have been lost, while others have dimmed. Some, however are still vivid. For example, Fumiko had found some leaflets dropped by an American plane, and when a Japanese lieutenant discovered that she had them, he slapped her face. On one occasion, we girls were ordered to collect any written things we had, as well as any pictures or money, and bring it all to a particular room in the cave. I had nothing but a picture of my real, older sister and her family. Through the misery of the past months, viewing that tattered but cherished picture from time to time had been a source of some comfort. The soldiers ordered us to put the pictures, letters, other papers, and money into a pile at the center of the room. We were told that everything must be burned because any such things that we carried might provide information of value to the enemy if we were killed or captured. I felt heartbroken as my picture burned, but I had been afraid not to turn it in. Another thing I remember is that one morning when I went to Colonel Ueno’s headquarters I met Colonel Ueno, Masako-Nesan, and some soldiers coming out of the cave. The colonel couldn’t walk and was being carried in a straw basket similar to those used by Okinawans for carrying such things as sweet potatoes. His usual smile and confidence were gone. He talked with me briefly. I can’t recall his words, but I do recall my tears at seeing him in this condition. He and Masako-Nesan were on their way to the Japanese Army Headquarters in a Mabuni cave where they later committed suicide.

We remaining girls and some soldiers moved into the cave that Colonel Ueno had just left. It was a great improvement over the miserable dark hole where we had been hiding. The end of the battle for Okinawa was very near, and there was much talk of suicide rather than being captured or killed by the Americans. I remember that some of us were called one day to sit in a circle in one of the cave’s rooms. At the center of the circle was an explosive device We were sitting in a circle on the cave floor as we had been directed. Death was imminent. I sat with my head down, quietly lost in thought as the others must have been. This was interrupted when a soldier came in from outside the cave and said that a general had ordered that all Okinawans were to return to their homes. No thought seems to have been given as to how we were to make our way through miles of fighting and carnage or even if our homes still existed. Nevertheless, Fumiko, Ha-Chan, and I obediently prepared to leave. The real families of all three of us lived near each other in Nakijin, so we were directed to leave together. I found what remained of my first-aid bag and put into it an explosive handed to me by a soldier. He said I should use it on myself if I was about to be captured by the Americans.

|

American soldiers at the mouth of an evacuation cave |

Five soldiers were to guide us as we started on our way. They preceded us out of the cave and into the night. Very quickly we became separated from them and were lost in the darkness. After wandering for a while, we found ourselves within a few yards of an American camp where soldiers were talking and laughing. Realizing our danger, I whispered to Fumiko to crawl away slowly, then I would follow at a distance. Ha-Chan would be third and would crawl quietly after us. Fumiko had left, and I had gone only a short distance when behind me I heard Ha-Chan call my name and begin running toward me in the darkness. Instantly there was gun fire from the Americans. Ha-Chan screamed and fell on top of me. I could feel her warm blood on my hip and leg. As we lay on the ground, the shooting continued. We needed to get farther away, but Ha-Chan was unable to crawl. I told her to hang on to me and for a while I pulled her as I crawled. Then she said she could go no farther but would follow me after she rested. I was to go ahead to Fumiko, and the two of us would wait for Ha-chan.

As daylight neared, Ha-Chan had not joined us. Fumiko and I quarreled. She wanted us to try to find our way back to the cave. I wanted to go into a nearby sugar cane field to hide from American patrols. In truth, however, I could not go on. I had become very sick and was burning with a fever. Without arguing any more, I crawled into the sugar cane field and Fumiko followed. We stayed there three days. My fever was so high and my thirst so great that after nightfall I crawled to the edge of the cane field. Nearby was a pool of water were I drank my fill before crawling back into the cane field. By early morning, I again needed water and crawled back to where I had drunk in the darkness. I discovered that the pool was simply a bomb crater and a dead soldier was lying in the water. I crawled back into the sugar cane. I lay there, too weak now to crawl and hardly able to move. My throat was parched from thirst. Fumiko broke sugar cane for me, but the sweetness only worsened things. She and I hardly talked at all. I was in a dreamlike state, having nightmares, maybe hallucinating. In the distance was the sound of trucks. Even today the sound at night of distant trucks triggers in me an empty, miserable feeling. Also in my dream-like state in the sugar cane field, there were recurring thoughts of Ha-chan. Fumiko and I had waited throughout the night as I had told Ha-Chan we would, but she never came. It was if I had neglected my responsibility for a little sister.

On the third day, I was still lying on the ground, and Fumiko was sitting beside me picking lice from her blouse. I heard rustling in the sugar cane and turned my head toward the sound. All I saw was many feet coming toward us. I whispered to Fumiko that she should put her head on me and we’d lie there unresponsive. She promised that she would not surrender. We were quickly surrounded by what seemed like fifty American soldiers standing in the sugar cane. All had weapons and they were pointed at us. Immediately Fumiko put her arms in the air and said, “American soldiers, help!” I was so disgusted that I didn’t speak to her at all in the following weeks. (Yet I was the one who eventually married an American.)

Fumiko was standing up but I was still lying on the ground. The soldiers motioned for me to stand. I shook my head. Angrily, two soldiers grabbed my arms and pulled me to my feet, but I collapsed. Then they saw the blood on my clothes where Ha-Chan had fallen on me after being shot. They thought I was wounded, and they realized that I had a fever. An interpreter asked where the Japanese soldiers were and we told him that we didn’t know. We didn’t even know where we were. Soon we were loaded onto a truck that had other Okinawans on board. Soldiers were passing out candy and things to eat, but all I wanted was water. I pointed to a soldier’s canteen, and he handed it to me. I drank so fast that he took it from me. He touched his watch and motioned so that I understood I should drink more slowly. His kindness was unexpected. Japanese soldiers had told us that the Americans tied captured civilians to the front of tanks as they went into battle and other stories of the terrible things that would happen to us if we were captured.

The truck finally got to our temporary destination, which we were told was what was left of the town of Itoman. I was taken to a dispensary tent right away and given medicine. Then the soldier who had given me water brought a young boy’s gray suit for me to wear. An Okinawan man snatched the suit away, but the soldier got it back and returned it to me together with some soap. He instructed me to “washy-washy.” Still using hand motions, he told me to throw my dirty clothes away, bathe, and put on the clean gray suit. He filled the tub, but I wouldn’t take my clothes off until he moved away. The odor of the soap was wonderful, and the bath, though brief, was heavenly. I hadn’t bathed for what seemed like ages. I was too weak to walk, but when I finished dressing, the kind soldier came to help me back into the tent. Others were given onigiri, rice balls, but I was still unable to eat so the same soldier brought me a canteen of lemonade. Later, there were more pills and more canteens of lemonade. Throughout the decades since then, I have thought often of that soldier’s kindness and wished that there were some way to thank him. Many other Okinawans must also have been relieved at the kindness shown to “captured” civilians because the Japanese soldiers had indoctrinated us with tales of the cruelties we could expect.

After the Battle

The next morning we were loaded onto trucks to be transferred to another location. We had no idea where we were being taken. I was uneasy and fearful as we traveled slowly northward, on pot-holed roads, past the ruins of Naha and other towns and villages that had been destroyed. Finally we reached a huge enclosure of tents and shacks called Camp Koza. Here, thousands of Okinawan refugees were being held. We were assigned to a tent with a floor of some wood and the rest of dirt and straw. I was taken to a dispensary and given medicines plus vitamins for beriberi. Soon I developed an odor which I hated. I was told that it was caused by the vitamin B.

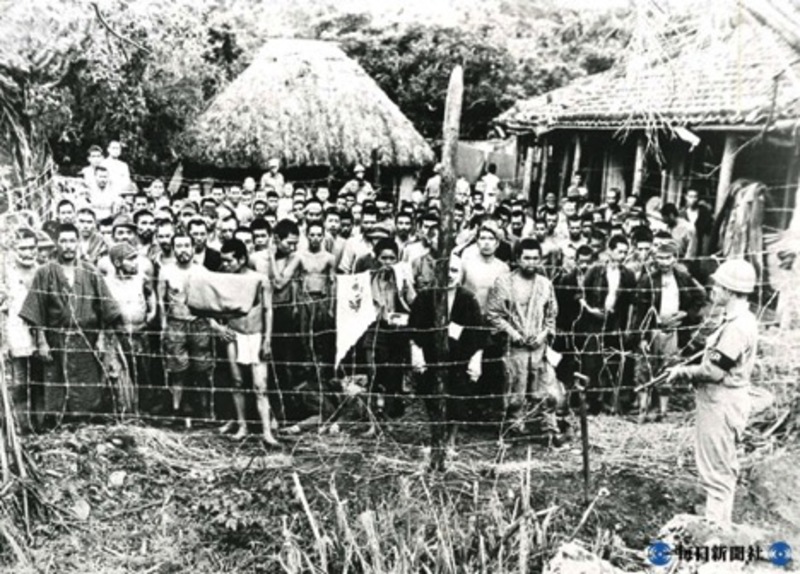

|

Refugee camp guarded by M.P.’s |

Still I was not speaking to my friend, Fumiko, who had broken her promise and surrendered to the Americans when they found us in the sugar cane field. She slept in one corner of the tent, and I slept in an opposite corner. In the daytime the tent was so noisy that I would crawl away to sit under a tree near the fence. Beyond the fence were Americans and, every afternoon, American music was played over a loudspeaker. I didn’t understand the words, but I loved the voice and songs of one vocalist in particular. A few years later, I learned that the one I enjoyed so much was Perry Como, the popular American singer. His voice was soothing and encouraging. By now I was hobbling along with the aid of a stick fashioned from a tree branch.

In the middle of August, when we were told of Japan’s surrender, I remember just being in a stupor, not knowing what the future would hold. The thing I wanted most was not to have to go back to Anmaa in Tsuji. We still were prohibited from leaving the refugee camp. Fumiko and I had begun talking to each other once more, but neither one of us knew what had happened to our families in Nakijin. We asked around in Camp Koza to see if we could find anyone from Nakijin which was many miles north of where we were. Someone told us that Nakijin had been destroyed and the people had all been killed. Fortunately, as we learned later, this was not true. We did hear that there were some people from Nakijin in Ishikawa, a much closer town, but one that we knew nothing about. Nevertheless, we decided to try to go there. First we had to get permission to leave Camp Koza. After that was done, we succeeded in finding an Okinawan truck driver who promised to take us to Ishikawa. As a result, after a few days, Fumiko and I were wandering the streets of Ishikawa asking if anyone was from Nakijin.

On one narrow, dusty street, I noticed a sign that said “Shinjo – midwife – Michiko.” In Nakijin there were many Shinjo families. In fact, Fumiko and I both were from Shinjo families though we were not kin, or certainly not close kin. Anmaa, who had bought me, was originally from Nakijin. She and other madams that engaged in prostitution usually found it convenient to buy girls from impoverished families in or near their own home villages.

Because the name Michiko Shinjo was on the sign advertising a midwife, Fumiko and I decided to see if this woman might be from Nakijin and might have news of our families. We went down an alley that led to a house bearing the name Michiko Shinjo. Cautiously, I opened the door a bit and called a polite greeting toward the interior. A woman’s voice answered, and as the woman approached the door, she and I both were startled. It was Yoshiko-Nesan, my favorite older sister who had been able to buy her freedom from Anmaa. She had changed her name from Yoshiko to Michiko. With the help of her patron, she had taken midwife training and now was a licensed midwife. I had not seen her since she had fled from Naha following the bombing and fire. At that time, she had stopped briefly in Urasoe when I had been there with Colonel Ueno and his soldiers.

We talked all that evening and through the night. She told me that our families, Fumiko’s and mine, had been evacuated from our home village to a place called Kushi and that she would help us arrange for travel there. Thanks to her help, several days later Fumiko and I were riding a bus north along a bumpy dirt road that followed Okinawa’s east coast. Despite the clouds of dust created by our bus, the countryside and the scenic ocean were beautiful. Except for the American soldiers that we passed, there was little to remind us of the terrible battle and devastation we had experienced farther south.

When we finally arrived at the evacuation center in Kushi, many people were milling about. Almost the first person I saw was Ha-chan. I could hardly believe my eyes, because I thought she was dead. As I have mentioned, after Fumiko, Ha-Chan, and I had wandered in the dark and had come upon a group of American soldiers, Ha-Chan had been shot. Since that time, I had dreaded my eventual meeting with Ha-Chan’s family and having to share with them the details of the sweet young girl’s last days. Now, here she was in Kushi, already having reunited with her family. She said that American soldiers had found her and at first thought that she was dead. When they discovered that she was alive, they took her to a medical unit. There, with prolonged treatment, she recovered and was released.

Then I saw my biological mother standing among the people. She had tears in her eyes. She told me that every day she waited as more people arrived, hoping that I would be among them. As we were engaged in this joyful reunion, a Korean interpreter employed by the Americans stood nearby and leered at me.

The compound for evacuees in Kushi contained many shacks that housed families or groups of people. My mother led me to the shack where my father was, and he expressed relief that I had survived and managed to find my mother and him. After the horror of the war, searching for my parents had seemed the only thing to do. Nevertheless, I now felt almost as if I was among strangers. My younger brother also was there. I learned later that during the battle he had been with Japanese soldiers, was wounded, and was taken into a cave. Without first aid treatment or medicines, his head wound festered badly. An Okinawan medic in the cave had urinated on my brother’s face to wash away the maggots. Following the surrender, many older Okinawan boys had been arrested and treated as prisoners of war. Some kindly Okinawans had hidden my brother, and he eventually was transported to a camp for civilians.

The following day I was outside the shack when I saw coming toward me the same Korean interpreter who had leered at me when I arrived in Kushi and was with my mother. His leering disgusted me, and I was frightened, so I ran to the shack of Fumiko’s family and hid. When I returned to my parents’ shack, I learned that he had gone there trying to find me. Fortunately, we didn’t have to stay in Kushi much longer. Following a severe typhoon, my family and others were returned to our home villages.

On arriving in Nakijin, we discovered that the houses in our little Imadomari neighborhood had been destroyed. We were told that when the Americans had found Japanese soldiers hiding in one house, all of the small, thatched-roof houses had been burned. Now my father and other men set about constructing shacks for shelter. Ours was right at the seashore and consisted of one tiny room where we lived and slept. My father was a fisherman, but fishing, as well as going out in boats, was prohibited, so we had almost nothing to eat. Farm families had sweet potatoes and some vegetables, but we resorted to collecting seaweed or wild greens by the roadside. Even the seaweed was “trash” seaweed that had washed up on the beach. At times we received limited food rations from the Americans, and my mother used such things as flour or small amounts of corned beef hash to make soup or dumplings.

|

Traditional home in Nakijin Village |

We had no utensils for cooking or eating and learned to retrieve things normally cast aside in order to fashion our own utensils. Pots and pans for cooking were made from cans of all sizes. We made drinking cups by using a wire to laboriously “saw” the top half of a Coke bottle away and then “file” the sharp edge smooth with a rough stone. The bottom half of a metal barrel could be placed on stones and, with a fire underneath, serve as a large cooking pot or bath tub. Weekly bathing involved one tub of hot water, with bathing priority beginning with the father, then sons by age, and ending with the youngest girl. A crude wooden platform enabled you to squat in the tub, keeping your feet from the hot bottom of the barrel. At other times, bathing was with cold water. Unfortunately, the stream that ran past our house to empty into the sea was generally so polluted by people living upstream that we couldn’t bathe in it.

There was little money, nor was there much opportunity in the countryside to find work. My father did make straw sandals as well as brooms from palm leaves. The few people who had things to trade or sell took advantage of the black market without much fear of punishment. Back at Kushi, when I found my parents, I gave my father the little money and few things of value that I carried in my tattered first-aid bag. Later, this enabled him to buy or trade for a bit of food and, of course, cigarettes and sake. With no jobs or organized entertainment, many of the young people often gathered after dark on the beach for what Okinawans call mo-ashibi, outdoor parties or revelries. Using roughly fashioned musical instruments, usually a three-stringed sanshin, they would sing late into the night. Their favorite gathering place was near our shack, and my brother always participated.

As the months passed, my family continued living “hand-to-mouth” with no prospect of things improving. Gradually my father’s mood changed, and I began to feel unwelcome. I wanted a job so that I could help my family, but there were no jobs in Imadomari. When my father suggested that I should go out and find a companion, I knew what he meant and I was heartbroken. He valued me not as a daughter and family member, but only as one who should be making money in what he felt was the only way I could.

One day I heard that there were jobs at a small installation the American Navy had set up in Toguchi, a village not far away on the Motobu Peninsular. Fumiko and I went there and succeeded in being hired as maids. This was especially good because the base had a place for the maids to live, and I didn’t have to go home at night. Among other things, I was responsible for cleaning the room of the commanding officer. He spoke a bit of Japanese and was very kind. I remember in particular that once in his presence I used curse words that I had heard frequently used by sailors as they worked. I did this, having no idea what the words meant. The Commander was amused, but he explained patiently that I should not use those words again.

After several months, Fumiko and I returned to Imadomari to visit our families. This was a mistake because my father, instead of appreciating the money I brought, insisted that I should quit my job as a maid at the Navy station. He said I could make more money “doing pom-pom,” that is, working as a prostitute. This hurt and angered me. He seemed unconcerned that my brother, who stayed at home without a job, spent his nights partying. I knew that I had to get away completely and talked about this with Fumiko. We made plans not to go back to the Navy base, but to leave and find other jobs farther away from home.

One night, without telling anyone, we left. There was no bus or other transportation so we walked along the dirt road, carrying what few clothes we had. Almost everything we wore was made from ripping apart American soldiers’ uniforms and underclothing, then sewing such things to fit us. As we walked, we met two dark-skinned soldiers who followed us and then began to chase us. Screaming, we ran as I have never run before or since. Fortunately, a Military Police jeep approached. When the Military Police offered us a ride home, we readily accepted. Fumiko and I were disappointed that our escape had failed but we realized that things could have been much worse.

I continued refusing my father’s plan to use me for supporting the family, but after several weeks I learned that he had a different idea. My brother confided that my father had agreed that, for a certain sum of money, I would become the “second wife” of a local man more prosperous than my father. The arrangement, my brother said, was to be concluded the following day. My father had forgotten, or had ignored the fact, that long ago he had sold me to Anmaa. Until someone paid for me, she still owned me. Even now Anmaa allowed me to stay with my family only because she had not yet set up a house and rooms. It was clear to me that I had to leave as soon as possible.

Very early the next morning I set out once again, this time without Fumiko. I was able to hitch a ride with an Okinawan truck driver. Okinawan people had no cars, few bicycles, and little money for the occasional bus, so everyone walked or hitchhiked. Okinawan truck drivers, whenever possible, were helpful to people needing to get from one place to another. I had planned to try to get a job at Kadena Air Base, but my truck ride ended in Ishikawa, where my older sister, Michiko Shinjo, was working as a midwife. When I went to her house, she met me at the door and asked where I was going. I told her Kadena Air Base to get a job. She told me to come inside and, to my surprise, there was Ha-chan. Michiko was so busy with her midwife job that Ha-Chan was living with her and doing the housework. Michiko said that she could help me get a job right in Ishikawa at a Rest Center for American officers and their families.

Working for the Americans

Michiko went to the Rest Center with me and I was hired. Also, I was provided a room of my own so that I might live right at the Rest Center. My job was to sell soda pop, beer, and a few incidentals in a small Post Exchange that occupied one corner of the large dining room and adjoining kitchen. An American Army captain was in charge of the Rest Center and had a staff of several soldiers. A few Okinawans who had lived in Hawaii played very important roles. One man was the interpreter and administrative go-between for the Americans and Okinawan workers. Another was responsible for all the baking, and his wife was in charge of the kitchen and dining room. The beach at the Rest Center was clean and very nice. It was surprising that such a peaceful scene could be found amid Okinawa’s devastation, disruption, and poverty. When I saw the American women in their swimsuits, it seemed to me that they all were beautiful. I was fascinated with the different hair colors of the American women.

My pay, even by the standards of that time, was poor, but I was proud of my job and worked very hard. Though I didn’t speak English, I managed to learn the names of the few things I sold and was able to receive payment and make change. When my little PX wasn’t busy, I helped in the kitchen. Most of the officers and families came to the Rest Center toward the end of the week or on weekends, so then we were exceptionally busy. At those times, when I was able, I also helped wait tables in the dining room. Once a young officer’s wife asked me to bring something to her table. I don’t remember now exactly what it was, but whatever I brought her was wrong. When she saw that, she broke out laughing and all the people at her table and nearby tables began laughing loudly. I stood there in the crowded dining room, humiliated, not understanding the joke but knowing I was the cause of it. Right there I made up my mind to learn English. For the next six months, I spent all of my spare time studying English with a woman working at the Rest Center who was from Hawaii. I began to be able to carry on a conversation. Soon, Mrs. Ishihara, who was in charge of the kitchen and dining room, made me her assistant.

I enjoyed working at the Rest Center in Ishikawa. For the first time, I felt safe and at peace with myself. After I had been there about two years, I had a message from Michiko who was still working as a midwife. She wanted me to visit. I took time from my job and went to her house. There she introduced me to an older Okinawan gentleman who hoped to form an all-female group of Okinawan dancers originally from Tsuji, the entertainment district in Naha. Knowing of the years of classical dance training I had as a child, Michiko had recommended me highly. The last thing I wanted, however, was to return to anything associated with my former life. As politely as I could, I declined. In the following weeks, Michiko called me back to her house five times, insisting that I join the dance group. Still I refused, and she became very upset. When she had been Yoshiko, my older sister, and then as a midwife with a different name, Michiko had always been helpful and kind to me, so it wasn’t easy to keep telling her no. This ended our friendship, but I was determined to continue with my new way of life.

A few months later, the woman in charge of the kitchen and dining room, Mrs. Ishihara, told me that our Army captain who oversaw the Ishikawa Rest Center had been tasked with establishing another Rest Center much farther to the north. Mrs. Ishihara asked me to go with her to help set up the kitchen and dining areas. As we traveled the dusty coastal road, there were forested hills and mountains to our right and turquoise waters to our left. I was amazed at the beautiful scenery. We passed many small villages before we reached Hentona, the village that was our destination. The new Rest Center was to be constructed on a nearby point of land called Okuma.

The proposed rest center site was rough and was covered in very tall, wild grass. As the Okinawan laborers cleared the land and began excavations, they caught many poisonous snakes, the Okinawan habu. I am deathly afraid of snakes, and we were sleeping in tents with all of our work being done outside. Soon I began to regret having come to this desolate place.

In addition to the few soldiers, there were Okinawan workers, and all had to be fed. Because the kitchen had not yet been built, we cooked on charcoal in barrels that had been cut in half out in the open. I remember holding an umbrella at times as I cooked. Within a few months, however, a kitchen, dining hall, and lounge had been constructed, as well as rooms for us to live in and cabins for the Rest Center guests. Though the military officers and their families had not yet starting to come to the Okuma Rest Center, there were the center’s startup staff, plus Okinawan laborers, and a few soldiers to feed. In the new kitchen, cooking became enjoyable once more.

One new staff member was Mr. Yamada who was from California. He and his wife often invited me to visit them in their quarters. During one of these visits, some leaflets were lying on the table. As I looked through the leaflets, one in particular caught my eye. I could not read the leaflets, of course, but I inquired about them and Mr. Yamada said that his family in Los Angeles had sent them. I asked if I might keep the one that so attracted me. He said that he would be pleased for me to have it and explained its religious significance. It immediately became, and remains to this day, a treasure to me, and I feel that in a way it watches over my family and me.

Things had been going smoothly for a while, with the Rest Center in full operation, when Mrs. Ishihara got sick and had me take over her responsibilities. She would come to the kitchen from time to time to help out because we had many officers and their families, especially on weekends. Under her guidance, I soon gained confidence in my ability to manage the kitchen. Before long, Mrs. Ishihara, as well as the American Army captain who had overseen the construction, left Okuma to return to the Ishikawa Beach Rest Center. I was put in complete charge of the kitchen and dining hall with a staff of eleven people. This was a high point in my life. I had received recognition for my ability and hard work, and things were going wonderfully. Or so I thought.

One afternoon Anmaa showed up. I couldn’t believe she had come; there were no buses, and traveling from place to place was still very difficult. She demanded that I return to Naha with her because she still owned me. She said that all of the other madams had their girls back, and I must go with her. I apologized, but told her that I was not going with her. She left in a fury. The following week she came back, insisting that I must go with her because she owned me. When I refused, we argued, and she went away, after warning me that she would continue coming back until I went with her. I realized that I had to find a way to buy my freedom from Anmaa.

Luckily, at about this time, an Okinawan woman asked me if I would save the kitchen’s bacon grease and sell it to her so I started collecting it in large cans. On one occasion, in the haste and confusion of preparing breakfast for a full dining room of officers and their families, I spilled a can of hot bacon grease on my arm. It burned so badly from the elbow down that I ran cold water on it, but there was no relief from the pain. I was taken to the dispensary where medicine and a bandage were applied. When my arm healed, there was no scar, and my respect for American medical treatment went up because as a child I had a similar burn on my leg and still bore the scar.

It took me well over a year to save one thousand yen from my bacon grease sales and my pay. This money I would use to buy my freedom, but as I didn’t trust Anmaa, I needed a witness to the transaction. For this, I asked the help of my biological older sister. She was my senior by about twenty years, and I hardly knew her. After the war, she and her husband with their children had returned to Okinawa from Japan and they now lived in Imadomari. She agreed to help me, and together we went to where Anmaa was staying with her brother. When we went into the house, I put one thousand yen on the table in front of Anmaa and said that this settled my debt to her. Then I bowed and thanked her. She was not pleased but told me that, because I refused to go with her, she would accept the money and set me free. When we left Anmaa, I could not stop crying. My freedom had become possible because of the help of many people and, of course, because of bacon grease. At that time, I did not know God but, if I had, I would have seen His hand over me and would have thanked Jesus.

Next, my sister and I went to our parents’ home to share the good news. My father was speechless. But he was not happy for me; he was upset over my having given my money to Anmaa. The following day I returned to Okuma, knowing almost overwhelming relief that I had shed my great burden. As a child and teenager, I went many times to the Naminoue shrine and prayed for escape from Tsuji by the time I was twenty-one. The horrors of war and the help of Americans had made it possible for my prayers to be answered. I had always daydreamed a lot and cried when I saw a wedding because such a life had not seemed possible for me. Now, though, I was free, and I hoped that I could marry someday like an ordinary person.

At some point during my work at the Rest Centers, I received a message from home. My older brother, Motoichi, was getting married. The wedding was to be at my family’s house and they needed my help. They wanted to build a house to replace the shack that had been put together when we were released from the refugee camp at the end of the war. I was able to buy lumber and send it by truck to Imadomari. They then constructed a house with a large front room, a smaller room behind, and a kitchen. The small room was for the bride and groom.

At the Okuma Rest Center, a new Army captain arrived to take charge. He turned out to be a considerate, well liked, boss. The center was becoming very busy, and soldiers were added to the staff, one sergeant even serving as cook. By the standards of that time and place, my wages were good. I was saving money and had managed to get some decent clothes. Then, one night someone entered the compound where we Okinawan women slept and stole most of our belongings. The Okinawan police came but were unable to determine who was responsible. We had lost almost everything, and nothing was recovered. My clothes were gone as were my other possessions. The captain did have some surplus replacement items for us, and at least I still had my job.

Steve Rabson is Professor Emeritus of East Asian Studies, Brown University, and a Japan Focus Associate. His other books are Okinawa: Two Postwar Novellas (Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley, 1989, reprinted 1996), Righteous Cause or Tragic Folly: Changing Views of War in Modern Japanese Poetry (Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 1998), and Southern Exposure: Modern Japanese Literature from Okinawa, co-edited with Michael Molasky (University of Hawaii Press, 2000). Islands of Resistance: Japanese Literature from Okinawa, co-edited with Davinder Bhowmik, is forthcoming from University of Hawaii Press.

Recommended citation: Masako Shinjo Summers Robinson with an introduction by Steve Rabson, “My Story: A Daughter Recalls the Battle of Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 7, No. 1, February 23, 2015.

http://japanfocus.org/site/view/4286

Steve Rabson is Professor Emeritus, Brown University and an Asia-Pacific Journal Contributing Editor. His latest book is

The Okinawan Diaspora in Japan: Crossing the Borders Within,University of Hawaii Press.

Related articles:

• The Ryukyu Shimpo, Ota Masahide, Mark Ealey and Alastair McLauchlan, Descent Into Hell: The Battle of Okinawa

• Michael Bradley, “Banzai!” The Compulsory Mass Suicide of Kerama Islanders in the Battle of Okinawa

• Sarah Bird with Steve Rabson, Above the East China Sea: Okinawa During the Battle and Today

• Yoshiko Sakumoto Crandell, Surviving the Battle of Okinawa: Memories of a Schoolgirl

• Aniya Masaaki, Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy