Brushing With Authority: The Life and Art of Tomiyama Taeko

Nobuko TANAKA

Introduction by Laura Hein

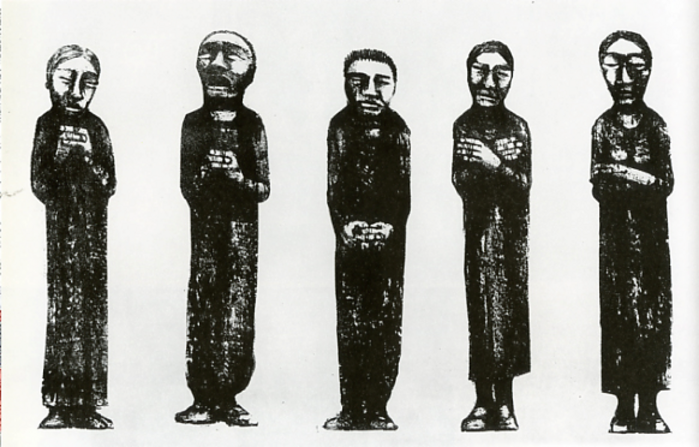

Like the reporter Nobuko Tanaka, whose 2010 interview with artist Tomiyama Taeko is published below, I vividly remember my first encounter with Tomiyama’s art. That was in 1984, when I visited the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum to see Maruki Iri and Toshi’s newly completed mural of the Battle of Okinawa, on display before travelling to its permanent home at the Sakima Museum in Ginowan, Okinawa (link). The adjacent room held a linked exhibit of Tomiyama’s black-and-white lithographs depicting Japan’s coal miners, including Koreans who had been forced to work in Japan’s wartime mines. I was just then writing about the history of labor relations in Japan’s coal industry, including the horrific treatment of Korean and Chinese slave workers during the war.1 Tomiyama’s images, such as “Sending off the Spirits of the Dead,” which evoked not only the Koreans who disappeared into the mines but also the families they left behind, impressed me as both social and aesthetic creations.

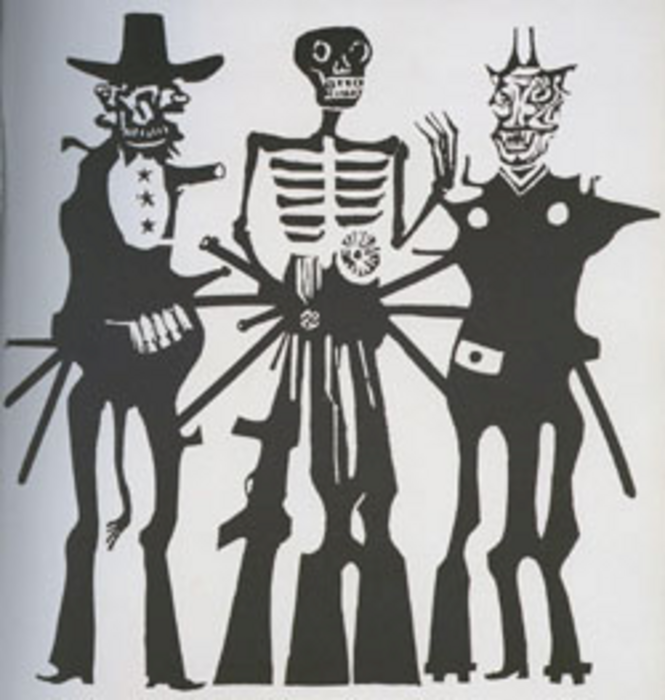

This artist had obviously thought deeply and creatively about how to depict the difficult subject of coerced labor. She forthrightly acknowledged colonial violence, something that was much less common in Japan at that time than it became in the 1990s. She was also clearly familiar with the international oeuvre of modern printmaking and its use as a medium of social protest, particularly early twentieth-century German prints. (Both the bold lines and savage irony of “Security Treaty,” reproduced below, for example, recall Otto Dix.) The images were hauntingly beautiful and stayed with me for a very long time.

Tomiyama’s goal is to bring back into view people who were systematically undervalued: for example, several works highlight the ways that modern societies accept the fact that women so often are cruelly used and discarded without any acknowledgement of, let alone opportunity to pursue, their own hopes and dreams. Her series of serigraphs called “Sold off to the continent” recalls both eighteenth-century woodblock prints and the remarkable extent to which both the modern Japanese state and ordinary families raised funds by sending young women to brothels at home and abroad.

The oil painting, “Let’s Go to Japan,” pictured below, brings this story full circle, now that young Southeast Asian women are trafficked into Japan. It is witty energetic, and hopeful, yet still conveys the artist’s scathing criticism of the limited set of choices these women face.

Much of Tomiyama’s work, as Tanaka explains here, depicts Japan’s colonial empire, its destructive wars in Asia, and the emotional and social legacies left by both war and empire after 1945. World War II brought suffering to all Japanese, but these memories trouble Tomiyama less today than does the knowledge that she participated as a school girl in the Japanese colonial system, and that her own government blighted the lives of others in her name. Perhaps Tomiyama’s greatest accomplishment is her honesty with herself about such issues. The recent international “memoir boom” and vast wave of books on remembrance of terrible historical events has centered on victims’ testimony to the trauma that has marked their own lives. Yet by expressing her empathy for others whose miseries she did nothing to prevent, Tomiyama is challenging the rest of us to change our behavior too. She has something important to say—the first and most crucial ingredient to powerful expression—and has found a sophisticated and imaginative visual way to convey it.

Tomiyama has been involved in leftwing politics since the early postwar years. For her, as for so many others, political community and creative practice are mutually constitutive and continually interactive. She is not quite as alone in this stance as she often feels, or as Tanaka’s interview suggests. For example, the Marukis were close friends for many decades, as the 1984 joint exhibit suggests. Tomiyama also worked with the late Matsui Yayori to build the Asian Women’s Association, which fostered dialogue among women in Japan and other Asian countries about human trafficking, sexual violence, and war responsibility. That organization later led to the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery in Tokyo in 2000. Her long-term efforts, and those of other Japanese like her, contributed to moving the subject of Japanese responsibility for war and empire to the forefront of debate after 1989. Tomiyama has also long been active in global peace and justice movements, such as support for the Korean democracy movement led by Amnesty International in the 1970s. Such transnational contacts have consistently sparked Tomiyama’s imaginative breakthroughs over the years, revealing the extent to which her creativity relies on breaking free from the confines of nationalism.

The clarity of her vision is reminiscent of Howard Zinn (1922-2010), her exact contemporary, who also came out of World War II with a burning conviction that wars produce no heroes, no moral purity, and much sorrow. Like Zinn, Tomiyama spoke for her generation’s lived experience that war both blinds people to their own ethical responsibility and encourages governments to oppress their own people. Like Zinn, too, she has been able to reframe this insight to capture the experience of younger generations time and again. Both individuals began reaching much larger audiences in their eighth decade of life. Tanaka Nobuko expresses her surprise here when she discovered that Tomiyama was a half-century older than she had expected, precisely because the art so beautifully captured the moral dilemmas of today. I discovered the same power to reach people of different ages, and in places far from Japan, when I organized an exhibit of Tomiyama’s work at my university’s student gallery in 2006.

Tomiyama’s appeal remains fresh because her thinking has evolved as she absorbed the implications of the social justice movements in which she participated. Most importantly she developed both an increasingly sharp critique of imperialism and a feminist vision. These issues for her are linked to each other and are also deeply personal. The experience of growing up in Manchuria contributed to Tomiyama’s sense of being neither fully an insider nor an outsider in Japanese society just as did the experience of growing up female. Like other colonial settlers, she enjoyed privileges compared to colonial subjects but also seemed discernibly foreign to inhabitants of the Japanese home islands. Tomiyama’s early frustration with the Tokyo political and art establishments in part reflects the alienation of a colonial settler returned to the metropole. After the war, that settler experience was suppressed from the Japanese postcolonial cultural imaginary, and Tomiyama rarely discussed it until decades later. This is a common experience for former settlers, both in Japan and elsewhere.2

Indeed, Tomiyama did not find ways to bring these life experiences into her art and into contemporary Japanese consciousness until the 1980s, when her art production became both more prolific and more profound. The vehicle that liberated her imagination was feminism, which provided a new grammar with which to articulate the meanings of both her own life and Japanese society. While creative work is always inherently autobiographical, feminism made this link more explicit to Tomiyama and provided new narratives to make sense of her life, ones that soon showed up as new interpretive strategies within her art. Feminism inspired her return to oil painting and also gave her the courage to fill very large canvasses, such as the brightly colored work, The Night of the Festival of Garugan [Galungan], a portion of which is reproduced below. Tomiyama’s images have gradually become less literal. She developed the metaphor of traffic between the world of humans and that of spirits in order to comment on relations of power within human society. Her work is populated with sly foxes, witty puppets, and the enigmatic shaman, an often female figure in much Asian folklore, who commands powers that are neither good nor evil. For example, the large gold canvas, Adrift II, shown below, was inspired by the December 2004 Asian tsunami. In her vision, by rending apart the natural order, the tsunami briefly allowed the creatures of the deep to come to the surface. These include fish but also the best features of local human cultures, cast off by contemporary Asians who no longer value their own creativity.

Tomiyama’s work is crammed with deceptively pleasant images that simultaneously lull and disturb viewers, who sense the malice implied just beyond the frame. One visitor to the 2006 exhibit wrote that “the pictures draw you into a world of shadows & nameless figures. It was an eerie feeling—like floating from one picture to the other. I cried, yet felt numb.” Another commented “This was beautiful. I could feel my own Asian history thriving in your images. The pains and torment of war;” while a third noted, “These images are wonderful, beautiful and frightening all at once. When I looked at them, I felt trapped in a sea of memories—and although they aren’t mine, I felt like I’d lived through them once too. So moving and effective!” Somehow, Tomiyama’s intensity came through to these young Americans 8,000 miles away.

Nonetheless, while these visitors admired her images, they often missed much of Tomiyama’s specific social commentary. Tomiyama draws on many Japanese and pan-Asian folk symbols and historical references, whose meaning are not immediately apparent to people unfamiliar with modern Asian history and culture. Her foxes may look cute but they are dangerous. When I showed her paintings to my students, the more I explained, the more they were engaged by what they saw. As I read through the visitors’ book in the exhibit, I found only a single entry that cut to the heart of Tomiyama’s visual symbolism, but that one comment rocked me back on my heels. “I am a survivor of torture. Thank you for your work. Telling the truth exposes the foxes.” Because of that visitor’s words, together with my students’ reactions, I decided to introduce Tomiyama more fully to English-speaking audiences through an edited book (with Rebecca Jennison),3 a website of Tomiyama’s work hosted at Northwestern University Library, and now this lively and engaging interview with Tanaka Nobuko of the Japan Times.

“Adrift II,” a 2008 oil painting by Tomiyama Taeko (trimmed). COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

Brushing With Authority: The Life and Art of Tomiyama Taeko

Sidelined in Japan, but respected the world over, Tomiyama Taeko explains what has inspired her art for more than 60 years

Nobuko TANAKA

I will never forget the day I went to a show titled “Embracing Asia: Tomiyama Taeko Retrospective 1950-2009,” which was one of 370 art exhibits by creators from 40 countries comprising the fourth Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial staged over 50 days last autumn at locations across a huge area of rural Niigata Prefecture.

Undimmed flame: Tomiyama Taeko pictured in the studio in her Tokyo home, with two of her oils on the walls behind, during the recent interview she gave The Japan Times.

“Normally people think negative things about getting old,” she observed with a smile, “but I enjoy my glorious 80s and, as I am an artist, I don’t have a retirement age and can just carry on working.”

Though virtually unknown at home, Tomiyama has, over her long career, had many excellent reviews for her exhibitions outside Japan, notably in London, Berlin, Paris, New York, Bangkok and Melbourne.

|

In 1995, she was invited to exhibit as a Special Guest at the first Kwangju Biennial Art Festival in South Korea, in honor of her many artworks based on the bloody, prodemocracy Kwangju Uprising there in 1980. Then, in 1998, she received the Women’s Human Rights Special Award from The Foundation for Human Rights in Asia. YOSHIAKI MIURA PHOTO |

Entering the exhibition’s venue, a disused but bright and airy elementary school in the village of Nakasato, beside the picturesque Kiyotsu Gorge, was in some ways like stepping into a modern-day but decidedly Asian Hieronymous Bosch festival. Among more than 200 of Tomiyama’s artworks on display were astonishing and stunning surprises at every turn — from woodcuts that brought to mind Fernand Leger or Pablo Picasso to surreal Asian histories in oils, silkscreens and graphically politically technicolor collages the like of which I’d never seen before. Never seen, especially in Japan, as the powerful, detailed and frequently comical, erotic or ironic content of many of the pieces spoke directly to issues so rarely if ever openly addressed in this country.

Surrounded by such a wealth of creative energy, my eyes were riveted to the displays. It was as if I’d stumbled into an artistic Aladdin’s Cave.

To my great surprise, I soon discovered that Tomiyama, the creator of these beautiful but clear and direct political and social messages — addressing festering sores such as Japan’s war guilt and countless global contradictions — was not a thrusting thirtysomething but a thrusting artistic agent provocateuse now in her 89th year. She was also someone I definitely wanted to meet.

Born in Kobe in 1921, Tomiyama was an only child who says she started to draw for want of having any playmates, but also because her mother loved doing beautiful embroidery. Her father drew cartoons as his hobby and sometimes invited friends who were professional suibokuga (Indian ink) artists to stay over.

When Tomiyama was 10, however, the family moved to Manchuria when her businessman father was transfered there by his company, the English-based Dunlop Tyre Corp. So it was that for the next six years, at an impressionable stage in her life, she lived in Dalian and Harbin — “witnessing both the conquering and conquered sides” in the puppet-state dependency that militarized Japan called Manchukuo.

But then, at age 16, Tomiyama moved alone to Tokyo to attend the Woman’s School of Fine Arts, later joining the Japanese branch of of the German-based Bauhaus School of art. Before long, Japan was at war, and by the time hostilities ended in 1945, Tomiyama was a “very poor,” divorced mother of two little girls.

Then, in the mid-1950s, when she returned to visit an area in Miyagi Prefecture in northern Japan where she’d been evacuated to during the war, Tomiyama was powerfully struck by the bare mountains swathed in black dust and smoke from the area’s coalmines. It was a sight that fired her artistic spirit and led not only to a series of writings and stark pictures on that brutal industry but to a turning point in her life that set her focus thereafter on social issues — something that even today many artists in Japan tend not to address head on.

Before long Tomiyama was off to South America on a shoestring budget to document the Japanese miners driven by poverty to emigrate there. Next she visited Cuba, then later, in search of her Asian roots, Central, West and South Asia. In the 1970s, deeply affected by the democracy movement in South Korea, she went to that country in turmoil and created a storied series of lithographs themed on the antigovernment poet Kim Chi Ha. That experience also fostered her continuing interest in and artistic focus on Japan’s annexation of Korea from 1910-45 — involving issues such as Japan’s many thousands of Korean “comfort women” (wartime sex slaves), her homeland’s largely ignored war guilt, and the present conditions of Asian women in general.

Yet though she is held in high regard and exhibited around the world, Tomiyama is virtually ignored in Japan — where the authorities ensure art and politics mix like oil and water — and her works are rarely shown even at small venues.

It was against this background that Kitagawa Fram, general art director of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, booked Tomiya’s show last autumn in that disused school. As he wrote in a review of her autobiography, “Embracing Asia,” published last year, Kitagawa did so simply because he believes Tomiyama “will in the future be seen as one of the best artists in Japan in this period.”

When I visited her home in Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward recently, Tomiyama put down her paintbrush, smiled warmly, and there in her sunny living room we started our conversation.

What’s this painting you are working on?

I am painting a landscape of Afghanistan, where I spent three months in the autumn of 1967. It is part of my latest series about the Eurasian continent.

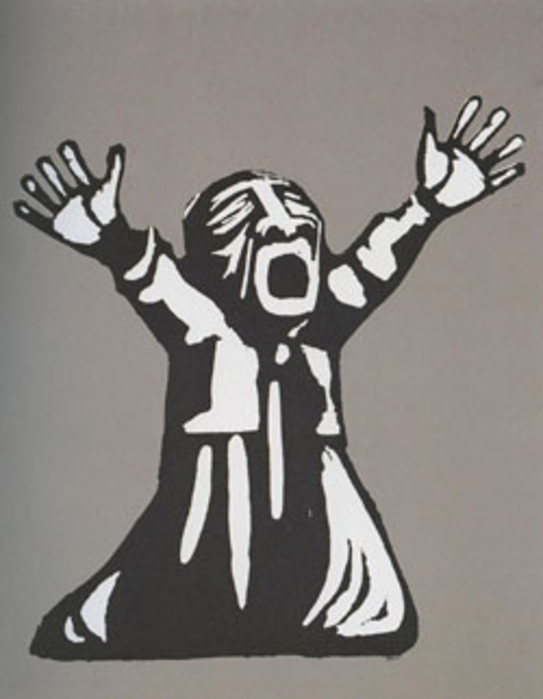

“Mother of Kwangju” (above) and “Security Treaty,” two (trimmed) 1980 Lithographs by Tomiyama Taeko referring to the bloody, prodemocracy Kawangju Uprising in South Korea in May 1980, and to 1960’s Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

When I went to Afghanistan there were no tourists at all, but there were those enormous ancient Buddha figures carved from the cliffs in the Bamiyan Valley. I remember I felt that there, somehow, was the indescribable origin of Japan, and also there I heard the local wedding music, and I thought it was very similar to the sanbaso music in Japan’s noh theater.

The Silk Road ran through Afghanistan, and that area was an ancient link between East and West. Alexander the Great went there from the West, and Buddhist culture also flourished there. So, with my Asian roots, I felt somehow nostalgic there though I’d never been before.

Everywhere, too, there was a kind of illusory surrealism, and the place was covered in liver-colored sands. I’m painting this from black-and-white photos I took then, and also from recent pictures, so I am creating an illusory image mixing ancient sights and ones from today. (Pausing as if struck by an urgent thought, Tomiyama then turned back to her canvas and painted some sheep on it without any hesitation at all.)

I notice that you can paint very speedily.

Now, in my 80s, I can paint much faster and more enthusiastically. I have much less hesitation to use my brush than before. When I was young, it took much longer to finish a work as I worried about many different things to do with my themes and their purpose. But now I am quite clear about many things, so I can work quickly. For example, if I took a year to finish a work in my 30s, now I could finish it in two months. There’s no point living for a long time unless at least some things improve, is there? (laughs) Normally people think negative things about getting old, but I enjoy my glorious 80s and, as I am an artist, I don’t have a retirement age and can just carry on working.

As for the subjects of my artworks, they have always come to me in a stream, such as the Gwangju Democratization Movement in Korea (1980) and 9/11 in New York (2001). So as long as I am ready to react to such matters instantly, I never need to worry about finding my themes and I feel free and relaxed to express my thoughts in my artworks.

When I went to the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial in the Niigata countryside last September, I thought I’d never seen such pictures as yours by a Japanese artist, as they obviously had such strong political messages.

Hmm, it’s been taboo for ages in Japan. It’s a tacit unspoken understanding in the Japanese art world to steer clear of politics because artists fear being branded as antiauthoritarian by the powers that be. That’s because those authorities are quite capable of ostracizing their work due to their groundless fears and lack of imagination.

Furthermore, commercial art galleries are hesitant to show such political and social works, as it may cause problems for their business, while the younger people who might want to plan such shows at public art spaces can’t get their bosses’ authorization, as they are afraid of causing controversy.

So do you mean there are certain taboos in art in today’s Japan?

In Japan, artists can’t indicate their political concepts clearly in their works, so normally they only allude to things in ambiguous ways.

For example, there is an unfathomable fog between citizens and the Imperial family in Japan. The Imperial family has never said that people shouldn’t make mention of its war guilt, but there is a certain unspoken agreement about not talking about war guilt in our society.

It would be something sensational, for instance, if celebrities were to talk about their memories of their experience in Harbin, Manchuria or Korea during the wartime period. Talking about Japan’s colonies is such a sensitive taboo in this country. I think it’s so weird. Of course, there is no problem if they just talk about their nostalgic, fun recollections, and it’s OK to praise the Imperial family. But once artists put critical or sarcastic messages about such things as war responsibility into their works, then it becomes quite unacceptable.

Unfortunately, artists are generally not well supported financially in Japan, so they tend to impose self-restraint in the interests of making a living. The same thing happens in the media, including television and newspapers.

Consequently, most of my exhibitions have been held in European countries, the United States and South Korea, because in those places there were no problems at all in showing my social-issue paintings and prints.

|

“The Night of the Festival of Garugan” (1988), an oil by Tomiyama Taeko (trimmed). NOBUKO TANAKA PHOTO |

In Japan, have you encountered any obstructions to doing your artwork?

We heard the news that the (left-leaning) Nikkyoso (Japan Teachers’ Union) annual meeting was canceled last year by a hotel due to a threat from rightwing groups. I’ve never heard of any other advanced country in which citizens can’t freely have such a meeting. As well, teachers are punished and can lose their jobs if they don’t stand up and sing “Kimigayo” (the national anthem) at school events.

There is collusion with the powerful, for example with the police, everywhere in this country, and citizens despair at that condition.

There were several threats from a rightwing group to the (left-leaning) Asahi Shimbun newspaper in the late 1980s, and since then the media has stayed away from troublesome matters as much as possible.

It’s all in line with that old proverb, “Don’t go asking for trouble,” and it applies equally to company workers, for instance, who normally worry about their long-term housing loans — so they don’t go asking for trouble.

In the 60 years since the war, such acquiescence to those with power has become so rooted in society without people really being aware of it.

Personally, I have always had pressures from rightwing groups against me holding exhibitions in this country. They don’t bother so much if I have a show at a university, as only a closed segment of people will see it, and they know it’s too immoral to rush onto a campus and start bellowing through loudspeakers at the students.

Funnily enough, though, those kinds of people don’t bother much about works of literature, because it takes time to read them carefully. But they can see paintings in a moment, so they can more easily target the fine arts.

|

“Let’s go to Japan” (1991), an oil by Taeko Tomiyama (trimmed). COURTESY OF THE ARTIST |

I wonder how much such largely unseen power pressures have destroyed the development of modern Japanese culture. Certainly, everybody knows it’s there, but as an artist I can’t just accept it in silence. However, artists have to think how to present their message cleverly under such conditions. That’s why the title of my exhibition at the Echigo Tsumari Art Triennial last autumn was the deliberately vague “Ajia wo Idaite” (“Embracing Asia”). So rightwing groups didn’t get there at all.

How did you come to be invited to participate in the Triennial?

The event’s general director, Kitagawa Fram, had been asking me for ages to stage an exhibition, and we had been waiting for the right opportunity. Then fortunately that closed elementary school became available as a venue. Also, although Niigata is traditionally regarded as quite a conservative area, I felt that the times have changed a bit these days — as we saw with the change of government in August after more than half a century of virtual one-party rule.

However, I don’t think there is any extreme message or propaganda in my paintings; they are quite normal, I believe. (laughs) In fact the school’s former principal came to see my exhibition and he enjoyed it so much.

Why do artists appear to behave so passively in the face of authority in this country?

In the long run, the arts have been ruled by the Emperor. The major art prizes, such as the Bunka Kunsho (Order of Culture) and the Nihon Geijutsuin Sho (Japan Art Academy Award), are bestowed by the Emperor, so inevitably they don’t go to people critical of the Imperial Family. And as artists awarded the Bunka Kunsho, for instance, can receive a special pension of ¥3.5 million a year, it’s to their financial benefit to stay eligible. Japan may not be a militarist country anymore, so anti- establishment artists aren’t locked up, but they just get ignored instead.

In my case, I’ve never received any form of official support, and as I am an outsider in the Japanese art world, you won’t find my name in art magazines.

In 1995, when an exhibition of my works titled “Tomiyama Taeko; Tokyo and Seoul Exhibition” was shown at Tama Art University as part of an art project commemorating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, a French staffer and a Japanese announcer from (national broadcaster) NHK interviewed me and made a program about my show. However, it was broadcast at 5 a.m. on a national holiday (Constitution Day), so nobody saw it or even knew it was on. Then I heard that those two people were transferred to regional offices soon afterward.

In the same year, that exhibition was also staged in Seoul with lots of local corporate support. In Korea, of course, the end of the war was their liberation from Japanese colonial rule, so most of the media covered the exhibition. A correspondent for the Asahi Shimbun also covered the show and sent a report to Tokyo, but it never appeared in the paper. In fact only Shukan Kinyobi (Weekly Friday), which is an independent magazine, ran a story about it here, but they didn’t mention it on the cover. . . .

|

Grand design: Taeko Tomiyama adds a few sheep to her work-in-progress, a landscape of Afghanistan, that will be part of a series about the Eurasian YOSHIAKI MIURA PHOTO |

Anyhow, after that business with NHK, I fully realized that only a few people would be ever able to see my works, so I now put together slide shows of them accompanied with beautiful music by Takahashi Yuji and it’s easy to take that anywhere and present a show, even in small community halls or wherever.

What were the reactions to your exhibition at the Triennial?

I personally was so shocked that there was such a huge response. There was a book at the reception desk where visitors were free to write their comments, and so many did — from small children to old people. Mostly they praised my works and many wrote long and earnest comments there.

In total, about 7,000 people visited the remote school to see my exhibition of about 200 artworks, so the festival organizers, too, were so surprised and delighted.

I am not entirely surprised, because that was quite a rare chance to see your works in Japan.

Certainly, I’ve rarely held any exhibitions in Japan in the last 10 years, and though it’s hard to present oil canvases overseas, friends in foreign countries have made tours with my screenprints, collages and slide shows.

Also, in 2004, an exhibition of mine, titled “Kioku to Wakai” (“Remembrance and Reconciliation”) was held in Philadelphia. It then moved to the Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, in 2005, and went from there to Northwestern University near Chicago in 2006, where it was especially well received. Consequently, a team at Northwestern led by Laura Hein, a professor in the History Department, is now making a Web site to show my works.

Do you think you will ever gain such prominence in Japan?

Well, even though Japan is changing slowly these days, it will probably take another 20 years before there is real change. (laughs)

Another reason I am overlooked in the Japanese art world is definitely because I am a woman. If I were a man, they couldn’t ignore me as they do — but it’s hardly surprising because I’ve heard its said many times by male artists that they don’t think women should discuss the society, and it shows an impertinent attitude if they do. They believe women should paint flowers, or Marie Laurencin- type graceful pictures. Feminist art only started in the ’80s in Japan.

How do you see the postwar development of Japanese art?

After the war, the dominant trends were abstract and fine art, as well as early homegrown Surrealism. And as artists were not inspired by Soviet-led Socialist Realism, they didn’t go that way. The upshot was that the majority of artists skipped over taking political and social subjects as their themes.

|

YOSHIAKI MIURA PHOTO |

When Japanese artists — usually men — take up the theme of the war, their works are always from the point of view of Japan’s victimhood and its sorrow and pain, not from an offender’s position. Most of the works show atomic bombs, Siberia or air strikes around Japan, but in terms of social responsibility I think we have to examine the offender’s side. And before they became nostalgic, I would like to ask them to think again why all those men needed to join the war. However, it’s taboo to represent our offender’s view, so when I painted pictures themed on Korean “comfort women,” I was attacked by many different groups.

Though we killed 20 million Asian people during the war, we never examine that history. There’s something wrong. It comes from people’s ignorance, but that’s hardly surprising because in the government’s school curriculum the modern history of Japan is just skated over, so young people don’t have that basic knowledge.

It’s all different in the world of theater, which can’t exist without social awareness. So there has been a social movement in postwar Japanese theater, and also in literature, but artists could escape into abstract expression.

What has motivated you to continue making your artworks even though you have been overlooked for so long?

My connection and friendship with foreign supporters has given me a great sense of purpose to continue. Also, there is no Emperor factor to deal with outside of Japan, so everything goes so smoothly.

When I wanted to hold an exhibition in a small Tokyo gallery in the ’70s related to Korean social issues (a lithograph series inspired by the Korean poet and thinker, Kim Chi Ha, who was jailed in 1975 for 5 1/2 years as a subversive by the then military government), the owner told me his gallery would lose dignity if he had that Korean-themed exhibition. He also said, in all seriousness, that he didn’t want to have Korean customers at his high-grade gallery. Maybe many people now can’t believe that, as there is a big Korean boom these days, but it was taboo to mention Korea or any of Japan’s other former colonies in the ’70s.

What do you think now drives today’s painters in Japan?

Well, if you asked them, most would probably say, “I like to paint pictures.” (laughs) But of course nobody asks artists here why they are doing what they do. Teachers never think about it, so they don’t ask their students.

|

Field studies: Taeko Tomiyama sketches on a spoil heap at a coalmine in the Kyushu city of Chikuho, Fukuoka Prefecture, in the mid-1950s. Her visit there and to other mines around Japan moved her to produce a series of writings and stark images depicting the harsh conditions that workers in the mining industry were made to endure. Those experiences were also a turning point in her life, as she afterward fixed her creative focus firmly on social TOMIYAMA TAEKO PHOTO |

In many ways, the quality of arts has gone down drastically since the end of the Edo Period (1603-1867). The works of many ukiyo-e artists stand comparison worldwide, and many artists early in the Meiji Era that followed were jailed for what they did or believed. They were real artists and artisans.

Then, once Western arts came to Japan after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, artists here just followed their lead. Now they generally accept the authorities’ evaluation without question. What caused such a decline after the brilliance of artworks in the Edo Period? When we lost the war, we had a great chance to revise our wrong direction, but we missed that chance and just closed our eyes. Nobody cared about the former colonies, and Japanese just made money from the Korean War procurement boom in the early ’50s. Then they got carried away by the ’80s bubble economy, when Japanese traveled around the world and spent money. What ridiculous nonsense.

Anyhow, I feel I’m not 100 percent Japanese — probably I’m half-Japanese. (laughs) I grew up in Dalian and Harbin, in the middle of the Asian continent, so I have always been watching Japan from the outside.

I suppose you met lots of young people at the Triennial. What did you think about them?

Two groups of young people planned tours to Niigata and went to see my exhibition. One was a feminist study group and the other one was a group studying the issue of wartime “comfort women.” The members of the former group didn’t know much about history; those in the latter group hadn’t much of a clue about art.

In contrast, in Germany the arts exist everywhere at citizens’ sides, so naturally ordinary people comprehend such concepts without any special effort. It’s the same in New York. So art in these places inevitably coexists with people’s awareness of social issues. Japan is in a period of transition in this respect: Artistic people normally know little of politics and social issues, and ideological people know little about the arts. At present, these two fields have not blended together.

Would you even tar the baby boomers in Japan who fought against the authorities as student activists in the ’70s with the same brush?

Those people are now close to retirement, and I know some of them are ready to do something good for the society in their extra free time. I think we may soon see grassroots activities involving such people rather than any large-scale movements. That’s probably the only hope for the future of Japan, because the official politics are hopeless.

What have you learned most from your experience in other countries?

|

Home comforts: Standing in the shadows in this family photo from the mid-1920s, Taeko Tomiyama poses at home in Kobe with her mother (left), father and an aunt. TAEKO TOMIYAMA PHOTO |

I was in Latin America for a year in the early ’60s and I felt so comfortable to be in multiracial societies. I feel rather out of place in monoracial Japan. When I went to New York in 1976 for my exhibition titled “Dedicated to Pablo Neruda and Kim Chi Ha” (a Chilean poet/politician and the Korean poet/thinker, respectively), I met and saw many student activists, people into women’s liberation and the “black is beautiful” movements. Previously, I had been so sympathetic with the student activism that happened in many places in the world in the late ’60s, and that had been one of the biggest influences in my life.

When I became an artist, I was one of the few woman members of the Jiyu Bijutsuka Kyokai (Free Artists Association) in Japan (one of the more liberal-leaning groups that at this point still dominated the country’s artistic landscape), but I came to think it was absurd to stay in such a closed arty society, feeling like a frog in a well, after I experienced those social movements in foreign countries. So I left that association and then found I had a lot more chances to meet like-minded people from different fields of the arts and other parts of society. One of those is the musician Takahashi Yuji, who has written accompaniments for my slide works. We have been working together for more than 30 years so far.

What turned me away from that association, too, was the way the male artists never accepted me as an artistic equal. They became very angry if I, as a woman, criticized their paintings. I was also so shocked when I saw how they treated their wives and the junior artists. I think Japanese men still want to hang on to the kuruwa bunka (red-light district culture) of the Edo Period.

I had such bitter experiences in that male-dominated society where, for example, the men would openly say such things as, “What do women and children know about anything?”

Who are the artists who have influenced you most?

That’s always changed depending on my age. First, when I was young, I liked Vincent van Gogh. Then I loved pictures by Marc Chagall, as they reminded me of things I saw in Harbin. Afterward, I went to an art college which followed the Bauhaus School in in Germany, so then I especially liked Paul Klee and Fernand Leger. I have also felt strong empathy with early 19th-century Surrealism, and from the postwar period I liked the German artist Anselm Kiefer and was hugely influenced by Russian avant-garde arts.

Just now I am keen on Inuit art from Canada. They observe nature and birds and other animals so carefully and put that into their art. They are fantastic.

Have you set any life target for yourself?

Nothing. (laughs)

I would like there to be as many memories of the war in my works as possible.

I can’t be so active as before, to be honest . . . so now I am painting this series on the Eurasia continent at home.

I’d also like to be a bridge between artistic people, who only know about the arts, and ideological people, who don’t care about the arts. So I occasionally go out to talk about such things from my experience and show my works in small seminars.

Tomiyama Taeko’s autobiography, “Asia wo Idaku” (“Embracing Asia”), was published by Iwanami Publisher in 2009. To learn more about her and her work, visit this site.

Nobuko Tanaka’s theatre blog is available here.

Nobuko Tanaka is a staff writer for The Japan Times. The original Japan Times story is here.

Laura Hein teaches Japanese history at Northwestern University and works on democratization in postwar Japan in a variety of institutional settings. She is an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator. This essay extends the analysis in the introduction to Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds. Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, forthcoming fall 2010. Link.

Nobuko Tanaka’s interview is reprinted from The Japan Times. Laura Hein wrote the introduction to this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Laura Hein and Nobuko TANAKA, “Brushing With Authority: The Life and Art of Tomiyama Taeko,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 13-3-10, March 29, 2010.

On related subjects see

Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka, Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States

elin o’Hara slavick, Hiroshima: A Visual Record

Jan Creutzenberg, Painters of Juche Life? Art from Pyongyang. A Berlin exposition challenges expectations, offers insights on North Korea

John O’Brian, The Nuclear Family of Man

Shinya Watanabe, Into the Atomic Sunshine: Shinya Watanabe’s New York and Tokyo Exhibition on Post-War Art Under Article 9

Nakazawa Keiji, Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

John W. Dower, Ground Zero 1945: Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors

Ken Rodgers, Cartoons for Peace: The Global Art of Satire

Notes

1 For a recent publication of photographs taken in 1945 of Chinese forced mine workers, see Carolyn Peter, A Letter from Japan: The Photographs of John Swope, Los Angeles: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts: 2006.

2 See Watt, “Imperial Remnants,” and other essays in Caroline Elkins and Susan Pederson ed. Settler Colonialism in the Twentieth Century, New York and London, Routledge, 2005. Mariko Asano Tamanoi, “War Responsibility and Japanese Civilian Victims of Japanese Biological Warfare in China,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 32.3 (July-September 2000): 13-22.

3 Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds. Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, forthcoming fall 2010.