Painters of Juche Life? Art from Pyongyang

A Berlin exposition challenges expectations, offers insights on North Korea

Jan Creutzenberg

(For additional images see The Gallery Pyongyang website.)

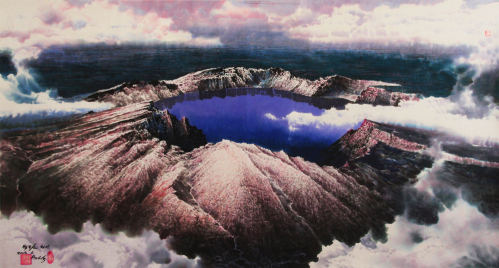

“Mt. Baekdu in June” by Kim Myong-un, 2006

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

Starving children, collapsing nuclear plants, a leader wearing sunglasses and a jump suit — when it comes to North Korea, the choice of imagery in the press is limited. Several coffee table books, illustrated travel accounts and even a graphic novel present impressions of empty boulevards, monumental statues, workers with a smile on their face and the colorful Arirang Mass Games.

But what about the image North Korea draws of itself? Recently a catalogue of propaganda posters presents a rather grim face with slogans ranging from “Death to US imperialists, our sworn enemy!” to “Let’s extensively raise goats in all families!”

The exhibition “Art from Pyongyang,” currently on display at the Art Center Berlin, shows different pictures: the “Hermit Kingdom” appears less industrialized and militarized, but rather idyllic. No wonder — for it is the first time North Korea’s Ministry of Culture officially held an exhibition abroad.

This is one of the few opportunities to catch a glimpse of North Korean paintings in the Western world. And it is also an opportunity for art afficionados willing to pay: Most of the works are up for sale, with prices ranging from 300 euros for prints to 10,000 euros for the ink drawings like “Sentiment of Autumn” by People’s Artist (the highest merit in the DPRK) Jong Chang-mo.

There certainly is a market for this rather unexplored region of the global art market. When British collector David Heather showed a number of works in a London gallery earlier this year, people were standing in line for hand-painted propaganda posters. In China, however, North Korean paintings can be bought in local galleries without much difficulty.

That is where Choi Sang-kyun, initiator of the exhibition and middleman for the North Korean officials, comes into play. Since he visited North Korea for the first time in 1990 (carrying an American passport), he got interested into the art production of what he calls “the northern part of my mother-country.” Will fine art from North Korea be the “next big thing”?

“I certainly hope so,” Choi says.

In cooperation with the German-Korean entrepreneur Inhee Chu-Mauer, he runs the Gallery Pyongyang that sells works by North Korean artists without a detour through China. Until now, this gallery existed “only in virtual reality,” but for some weeks it found a temporary home at the Art Center. The International Delphic Council, a non-profit organisation that reintroduced the artistic equivalent to the Olympic Games (the Delphic Games) in the 90s, gave the initiative for this event, in the hope of a peaceful dialogue with the world’s most secluded country.

So much for the complicated background of the exhibition. But what can we actually see there? Large ink drawings, many of them in color, show mostly landscapes, animals or plants: Torrents, canyons, mountain lakes, cherry blossoms, eagles and a swarm of shrimps. In fact, these light subjects were “allowed” by Kim Jong-il only in the 70s.

“Shrimps” by Choi Gye-keun

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

Some pictures feature traditional East Asian drawing techniques that can be found in historical and contemporary works from Japan, China and — of course — Korea. These are bordering on abstractionism, while other paintings are reminiscent of the dramatic cliffs and glowing skies depicted by romanticist painters like Caspar David Friedrich or postcardish impressionism, a few even look like hyperrealistic computer animations — images from a non-existent place?

Whether or not these pictures represent North Korean reality is obviously not the question here. It is rather our own expectations that come to the fore: Where are the children, the peasants, the workers and the soldiers? Where is the Socialist realism? Where are the traitors of the people and the “Mi-je,” the American imperialists?

Is this really purely decorative art — “Art without Kim,” as a leading German newspaper called it? For a number of reasons, I do not think so.

First, many of the seemingly apolitical subjects have specific ideological implications. For example, Mount Baekdu, the worshipped site of Korea’s mythical foundation, can be seen in numerous pictures, in varying styles and from different perspectives. According to his official biography, however, Mount Baekdu is also the birthplace of Kim Jong-il.

“Eagle of Mt. Baekdu” by Kim Sang-jik, 2008

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

“Lake of Mt. Baekdu” by Bang In-su, 2008

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

“Mt. Baekdu in May” by Choi Chang-ho, 2008

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

In this context a splendidly depicted landscape turns into an indirect celebration of the “Dear Leader.” Even some innocent plants hail to the glory of the Kims: Cho Won Du depicts “Kimilsungia” and “Kimiljongia,” elevating these cultivated hybrids to the ranks of the classical subjects for flower drawing.

“Kimjongilia” and “Kimilsungia” by Cho Won-du, 2008

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

Second, the paintings are representative of the production process, which in turn is embedded in the social system of the Juche state. In North Korea artists are primarily workers: Their ateliers are located in factory-like workshops, complete with monthly salaries and output-quotas, and if the employer — that is the state — is not satisfied, corrections have to be made.

Theoretically, the concept of the painter as laborer is completely at odds with any notions of artistic genius. This is not visible, however, in the hanging and labeling of the pictures that resemble common gallery standards. While there are no solo exhibitions in North Korea, the most famous painters, several of which are represented in Berlin, are highly merited. Some even were allowed to travel abroad on the occasion of this exhibition.

Third, the selection of pictures may tell even more about the current policy than the pictures themselves. Most of the artists featured have earned high titles and have won prizes. It is not only the arts that rely on veterans in North Korea, a situation not uncommon in revolutionary states’ coming-of-age.

Neither is the strategy to present the more bucolic sides of the national art production to the outside world, while sparing the more suggestive imagery for its own citizens. Still, the complete absence of anti-American slogans is astonishing. In the light of an anticipated regime-change on the other side of the Pacific, maybe this is an indication of a more conciliatory attitude towards the “sworn enemy.”

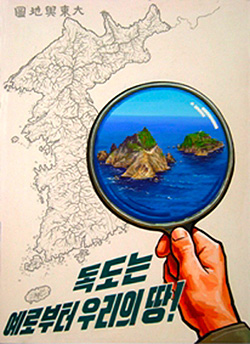

The few more explicitly political works are shown in two cabinets and tend to be rather mellow. There are two posters that use the style reserved for propaganda. One celebrates Kim Dae-jung’s and Kim Jong-il’s Joint Declaration of June 15, 2000 with colorfully dressed children (“We want to live in a re-unified fatherland”). The other one declares that “since the old days Dokdo belongs to our territory” — more than a few South Koreans might agree.

“Dokdo is our territory since the ancient time!” by Kim Gwang-nam

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

A large-sized oil painting shows a nurse vaccinating children in the countryside. Under her white lab coat she is wearing the party’s uniform. In the background villagers bid farewell to a tank. It looks like Russian or Chinese illustrations of respective governmental programs in the style of Socialist Realism from the 60s or 70s. However, the paint may still be wet, as Jong Myong-il finished his work only last year: it is dated “Juche 96,” which means 2007, counting from Kim Il-sung’s birth in 1912. Art history is ticking slowly in North Korea.

“The new looks of An-byon” by Ri Song-hak, Juche 95 (= 2006)

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

“Day of vaccination” by Jong Myong-il, Juche 96 (= 2007)

©2008 Gallery Pyongyang

The most interesting work, however, is “The new looks of An-byon” by Ri Song-hak, a panoramic view on harvest festivities in a rural town. Dancers, musicians and acrobats, dressed in colorful costumes, join uniformed communists who give rice as a present to the people. All over the place are banners featuring, clearly legible, most of the classical Juche slogans: “Long live the glorious Worker’s Party of Korea!” “Ten million soldiers, united like a single heart,” “Rice equals Socialism.”

Content-wise, traditional performance practices and Communist Agitprop (a term meaning revolutionary agitation and propaganda) intermingle on the village square. But the picture also combines different styles to a more or less harmonious whole. The miniature people are drawn “realistically,” while the mountains and fields in the background and especially the tree full of fruit that cuts into the foreground are clearly reminiscent of the “traditional” drawing mentioned earlier.

The Opening (left to right): Choi Sang-kyun (curator), Christian Kirsch (Int. Delphic Council), Hong Chang-li (ambassador DPRK), Inhee Chu-Mauer (sponsor), Kim Dae-hi (Ministry of Culture, DPRK)

©2008 Choi Sang Kyun

This may be an artistic representation of the combined Nationalism and Communism that characterizes the art of Socialist Realism as well as Juche ideology. It is rarely known that not only Stalin and Mao coined this claim. Kim Il-sung, author of several treatises on the arts, also joined the chorus.

In summary, his exhibition definitely is haunted by the Kims. And while the “Dear Leader” makes himself scarce in real life these days, he was present at the opening ceremony on Sept. 1, alongside his father — as paintings on the wall. Next to them Hong Chang-li, ambassador of the DPRK in Berlin, held a speech and Choi Sang-kyun, a trained opera singer, performed a North Korean song. The pictures of the Kims were removed later, maybe as an invitational gesture to the South Korean ambassador who did not attend.

This article appeared at OhmyNews on September 25, 2008 and was posted at Japan Focus on September 27, 2008. The website of the Gallery Pyongyang is available here.

Jan Creutzenberg writes on Korean arts, literature and film for Ohmy News.

Notes

The exhibition is on display until Sept. 30, for more information see the Web site of the Art Center Berlin.

The Web site of the Gallery Pyongyang.

An introduction to North Korean propaganda posters can be found here.

Jane Portal gives an overview on various aspects of the artistic production in the DPRK in her monograph “Art Under Control in North Korea”, published by Reaktion Books in 2005.