Recent Developments in Korean-Japanese Historical Reconciliation

[Japanese and Korean language texts available below]

The Hankyoreh and William Underwood

Following through on a pledge made in early 2010, the Japanese government in late March supplied the South Korean government with a list of 175,000 Koreans forced to work for private companies in Japan during World War Two. The long-sought records include details about the 278 million yen (about $3 million, unadjusted for interest or inflation) in wages the workers earned but never received. The funds reside in Japan’s national treasury today; the government has never indicated what it intends to do with the money. The data will enable authorities in Seoul to verify the forced labor experience of individuals listed in the records, and to finally compensate them under a South Korean program set up in 2007.

|

After decades of rebuffing requests for such information, Japan on March 26 provided South Korea with payroll records for Korean labor conscripts whose wages are now held by the Bank of Japan. (Yonhap News Agency) |

South Korea took that step in response to domestic political pressure that began building in 2005, when the state made public all of its diplomatic records related to the 1965 Basic Treaty that normalized relations with Japan and provided South Korea with $800 million in grants and loans. Those records show that the Park Chung-hee administration rejected a Japanese proposal to directly compensate wartime workers, while claiming for itself the responsibility of distributing funds received from Japan to individual Koreans harmed by forced labor and other colonial injustices. In fact, nearly all the money went toward economic development and national infrastructure projects instead. Courts in both nations have since concluded that the bilateral accord waived the right of South Korean citizens to press claims against the Japanese state and corporations.

Reparations questions were rekindled in March, however, when it became known that Japan once understood the treaty very differently. The same year the treaty was signed, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) interpreted the claims waiver language as being “legally separate from the individual’s own right to seek damages.” Japan’s 1965 stance was outlined in internal MOFA documents made public in 2008, in response to ongoing legal efforts by Japanese citizens to obtain information about the treaty negotiations. The documents were cited by Japanese lawyers representing Korean ex-conscripts in a case decided in March 2010 by the Nagoya High Court, which rejected the plaintiffs’ demands for compensation despite finding that involuntary, unpaid labor had occurred.

Apparently seeking to preserve legal options for its own citizens, the Japanese government has similarly claimed that neither the 1951 treaty it signed with the Allied nations nor the 1956 treaty it signed with the Soviet Union extinguished the right of individuals to pursue redress for war-related damages. But in the many dozens of lawsuits against Japan brought by citizens of its wartime enemies and former colonies, the government has consistently argued that its postwar treaties did extinguish the individual right to file claims. Compensation lawsuits by Korean, Chinese and Allied POW victims of forced labor all have ultimately failed on these grounds.

Last fall Nishimatsu Construction Corp. agreed to voluntarily compensate former Chinese workers, following the Japan Supreme Court’s ruling three years ago that the 1972 treaty between China and Japan barred legal claims against the company or Japanese state. Negotiations concerning a second settlement between Nishimatsu and a different group of Chinese plaintiffs have reached an acrimonious impasse due to disagreements over the amount of compensation and the company’s expression of responsibility. Other Japanese companies, now effectively protected by legal immunity, have indicated their willingness to settle Chinese forced labor claims on the condition that the Japanese government participates in the process.

The MOFA documents “will not change the Japanese government’s stance or influence court decisions,” according to Choi Bong-tae, a Korean attorney involved in the continuing wave of litigation. “But they will serve as valuable resources in demanding the Japanese government and businesses make voluntary compensation.” The most successful cases within the global trend toward righting historical wrongs tend to be legislative in nature, although decades of lawsuits in various countries targeting Japanese war misconduct have been invaluable in terms of truth telling and mobilizing international opinion.

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak is attempting to engage Japan on historical issues in a less confrontational manner than his predecessors, but the past remains ever-present in this centennial year of Japan’s 1910 annexation of the Korean peninsula. In the wake of the revelation that Japan once considered only state-level claims to have been waived, South Korean officials suggested that the “comfort women” injustice remains uniquely in need of a more sincere response from Japan. Former President Roh Moo-hyun asserted in 2005 that the Basic Treaty did not legally apply to the “comfort women,” Korean victims of the atomic bombings, or Koreans stranded on Russia’s Sakhalin Island after the war.

In late March, however, it was reported that Japan considers the redress rights of Korean former forced laborers repatriated from Sakhalin to have been waived by the 1965 pact – even though they returned home and obtained South Korean citizenship in the 1990s. This prompted Seoul to reiterate that the Sakhalin Koreans were not covered by the treaty and should be compensated by Japan. Meanwhile, basic facts about the forced labor system continue to emerge, with a South Korean truth commission announcing in February that most of the 6,000 Korean conscripts mobilized to Micronesia between 1939 and 1941 died before war’s end.

The one-hundredth anniversary on March 26 of the execution by Japan of Ahn Jung-geun, a Korean patriot and early pan-Asianist, underscored history’s impact on contemporary international relations and geopolitics. In 1909 Ahn assassinated Ito Hirobumi, the first Japanese governor-general of Korea, in Harbin, China, to protest Japanese rule. He was hanged in Dalian the following year. Viewed as a martyr and a visionary by many Koreans, and particularly by proponents of Korean reunification and East Asian unity, Ahn is considered a hero by some in China (but presumably a terrorist by some in Japan). On the anniversary of his death, the Chinese government temporarily closed the Harbin train station where Ito was killed to allow Ahn’s own death to be commemorated at the site.

Ahn’s final wish was that he someday be buried in a free Korea, but the location of his body remains unknown. Japan was criticized last month for not doing more to help track down the body, and even for concealing records that could assist the effort, although Seoul’s own commitment to the quest has also been questioned. An inter-Korean team searched for the burial site in Dalian in 2006, while South Koreans excavated in the area for a month in 2008 without success. A new high-level push to bring home Ahn’s bones has been announced.

Also last month the second Japan-South Korea joint historical study group released a 2,000-page report that was three years in the making. Regarding the colonial era of 1910-45, one Korean newspaper opined in an editorial called “Still Poles Apart” that the two countries have a “very long way to go before reaching even a semblance of common concepts on their shared history.” Yet alongside the frequent state-level friction, reparations work is steadily bearing fruit at the level of transnational civil society. Last August, during a month when Japanese media annually recall the nation’s own wartime suffering, a leading news program highlighted a Korean documentary about an apology by an elderly Kumamoto physician for the 1895 murder of Korea’s last ruling empress.

|

Kawano Datsumi (right), a grandson of Empress Myeongseong’s assassin Kunimoto Shigeyaki, apologizes to Yi Chung-gil, a grandson of Emperor Gojong at Hongneung, the royal couple’s tomb, in Namyangju, Gyeonggi Province, in May 2005. (Chosun Ilbo) |

The 84-year-old man, the grandson of the leader of the team of Japanese ultranationalists who assassinated the empress, traveled to Seoul with a group called the “People’s Meeting in Memory of Myeongseong” and tearfully asked for forgiveness at the royal tomb. The murder of the empress was cited by Ahn Jung-geun as one reason for assassinating Ito Hirobumi a decade later. “Hizendo,” the sword used to kill Myeongseong, has been located at a prominent shrine in downtown Fukuoka. Last month a committee of Korean cultural and religious leaders began working to have the sword destroyed or sent to Korea; Hizendo’s days at the Japanese shrine are likely numbered.

The package below consists of six articles from The Hankyoreh. Parts four, five and six of the South Korean newspaper’s “Traces of Forced Mobilization” series discuss Japan’s museum for kamikaze pilots, Koreans convicted of war crimes while serving in the Japanese military, and efforts to fill in historical gaps concerning civilian conscription. A related article describes the recent repatriation to Korea from Japan of 94 sets of civilian conscript remains, part of an ongoing community-level project. Then a Hankyoreh news story and an editorial connect Ahn’s legacy to the unfinished business of Korean reunification and peace building in East Asia based on his vision of post-nationalism. -William Underwood

Traces of Forced Mobilization – Part Four – February 16, 2010

English / Korean / Japanese

“Peace” Museum Glorifies Young Conscripted Korean Kamikaze Pilots

The exhibit includes 11 Koreans on display, including officers who were 17 years old at the time of their death

Kim Hyo Soon

On Jan. 20, I paid a visit to the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots in Chiran, southern Kyushu’s Kagoshima Prefecture. Among the various types of special forces under the command of the Japanese military, the Chiran kamikaze pilots were a suicide squad that would fly a small fighter plane into enemy vessels carrying 250 kilograms of explosives. “Chiran” has now become synonymous with the kamikaze pilots. The museum currently displays notes, diaries and letters left behind by those who died in battle, as well as photographs showing the squad members’ daily lives and real examples and restored models of the fighter planes that were used.

The atmosphere was strange from the moment I made the preliminary request to investigate the story. When I informed them of my plans via e-mail and fax, they sent me an application form. In addition to requests asking for the goals and methods of the investigation and the name of the person who would be handling it, there was another request in their note. It stated that it was forbidden to insult the squad members who died in combat or their family members, and that taking photographs within the museum is prohibited.

It takes about one hour and twenty minutes by bus to go from Kagoshima Central Station to the museum, which is located in the Chiran-cho neighborhood of Minamikyushu City. When I informed the information bureau of my business, an old man named Matsumoto Junro came out to meet with me. The job title listed on his business card was “advisor,” and he was 82 years old. He told me that two of his classmates from middle school had joined the suicide squad and died in combat, and he spoke about the museum’s exhibits like some kind of walking encyclopedia. On the right-hand wall inside the entrance were photographs or portraits of 1,036 people, along with brief personal information about them. I was told they were arranged according to date of death and squad.

Matsumoto pointed to one of the many photographs and began his explanation. The individual’s Japanese name was Okawa Masaaki, with the Korean name Park Dong-hun. He had come from Hamju County in South Hamgyong Province. He died on Mar. 29, 1945, in the 15th class of the Youth Pilot Training School. He was the earliest casualty of the 11 Koreans shown in the exhibit, 17 years old and with a rank of second lieutenant. Matsumoto asked how it was possible for a 17-year-old to become a second lieutenant and then answered his own question. Students who completed the Youth Pilot Training School curriculum were given the grade of staff sergeant, a noncommissioned officer position. As a rule, the Japanese Empire gave a special two-grade promotion to people who had died participating in the special forces. However, Park was made into a second lieutenant, perhaps out of the notion that a military hero would require an officer’s rank. Matsumoto said, “The surviving family members of those from South Korea do visit the museum, but there is almost no contact with the families of those from North Korea.” Three of the Koreans on the wall are listed only by their Japanese names, as their Korean names have not been found.

The history of Chiran as a kamikaze village started in late December 1941, just after the Pearl Harbor attack, when the Tachiarai campus of the Youth Pilot Training School was established. The students, who had been training with the “Akadonbo,” or “red dragonfly,” were sent into suicide attacks when the tide of the war turned against Japan. The museum commemorates the casualties among the army special forces unit members who took part in the Battle of Okinawa from late March to early July 1945. Located around the site are sanctuaries for the soldiers with images of the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy, who is said to turn nightmares into pleasant dreams. Also present are shrines dedicated to patriots and memorial stones erected for the different “graduating classes” by surviving classmates. Listed among the names of those erecting monuments are Koizumi Junichiro, the man who insisted on worshipping at the Yasukuni Shrine while serving as prime minister and Ishihara Shintaro, the current Mayor of Tokyo who has not shied away from making extreme right-wing remarks.

|

A statue glorifying the kamikaze special forces is located at the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots. (Hankyoreh) |

Inside the museum hangs a large chart showing the numbers of casualties by region of origin. It starts with Hokkaido in the north and travels down to Kagoshima, passing through Okinawa and Karafuto (Sakhalin Island) before arriving, at the very end, at Korea. A Japanese person looked carefully at the chart before remarking to a companion, “Oh, there are Koreans on there, too.” There is no explanation anywhere in the exhibit for why Korean names are listed among the fatalities, nor can one find any comment on the misguided measures of the Japanese leadership in hurling young Japanese men into an abyss of tragic death. When asked what he thought about critics’ charges about the glorification of a misguided war, Matsumoto responded, “That is something for each individual to view and feel for himself.” It was impossible to erase the overall impression that the site was enjoying tourism benefits by selling the souls of young men who died absurdly tragic deaths. Matsumoto said that some 500 thousand people visit every year, through school trips and other means. On my way back, the use of the English name “peace museum” weighed heavily on my mind.

Young university and flight school students were selected for kamikaze runs based on their dispensability

Kil Yoon-hyung

The suicide squads that we refer to as “kamikaze” squads first came into the Japanese military in October 1944, when the Imperial Japanese Navy’s First Air Fleet, whose headquarters were located in the Philippines, formed a special forces unit called “Shinpu Tokubetsu Kogekitai.” (“Shinpu” and “kamikaze” indicate the same Japanese characters, the former pronounced in the Sino-Japanese “on” reading and the latter in the indigenous Japanese “kun” reading.) After this squad carried out attacks on U.S. vessels at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, it became an emblem of the “kamikaze pilots” carrying out suicide attacks on the enemy with their own bodies.

The kamikaze pilots did not have the possibility of living or dying depending on their outcome. Their tactics were based on dying, and so while the forces adopted the process of “volunteering,” this was essentially no different from coercion. Since Japan could not use for such “one-time-only tactics” the kind of professional soldiers who had come out of military schools and received a long period of training, student soldiers whose enrollment had been cut short and young men in their late teens were selected, taught how to pilot an airplane, and then sent to their deaths.

Among the routes for selecting participants in kamikaze squads were the Youth Pilot Training School, which gave young men in their late teens a little over a year and a half of training in piloting techniques, and the Special Flight Officer Training School, which provided flight training to anticipated graduates from universities and professional schools and sent them into battle with officer status. Of the sixteen Korean kamikaze pilot fatalities confirmed to date, eight were from the Youth Pilot Training School and five were from the Special Flight Officer Training School, while only one, Choi Jeong-geun, came out of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy.

It would not be too much to say that the kamikaze pilots had practically no tactical value. After the initial shock of their existence wore off, the U.S. fleet’s response capabilities increased, and the success rate of attacks ended up at just around 6 percent. Lee Hyang-chul, professor of Japanese economies at the Kwangwoon University College of Northeast Asia, said that the kamikaze pilots represent a “tragedy unprecedented in human history, where in order to prevent the depletion of professional soldiers, the best and brightest from the era’s universities and young men in their teens were used as disposable ‘human bombs.’”

Traces of Forced Mobilization – Part Five – February 24, 2010

English / Korean / Japanese

Remaining Korean War Criminals Struggle to Find Their Way in Society

Conscripted soldiers who were convicted of war crimes faced hardship following their release from prison with no place to go

Kil Yoon-hyung

Kim Seok-gi, 89, met with the reporting team amid some far-off chaos. Kim said, “We built a palm tree house. Didn’t I say to watch them since you have a sword? Oh my. That we do not know now. Since things have turned out this way, I do not know exactly.”

Kim, who seemed to be trying to explain something, closed his mouth as he frowned. What he was trying to convey could not be put into language, and the interview ended in this manner. His wife Jeong In-sun, 73, who was sitting beside him, wiped his brow, and explained that since a stroke three years ago, he has good and bad days, and it is difficult at times for him control his behavior.

Kim is the only Class B/C war criminal still alive in Korea. He was tried as a war criminal and sentenced to seven years in prison for beating prisoners of war (POWs) at the Makassar Plantation POW camp on the island of Java during the Pacific War in what is known today as Indonesia, then a Dutch colony. In Japan, there are several surviving members of the group founded for and by Korean Class B/C war criminals to live well through mutual assistance, the Dongjinhoe (moving forward together). But with the exception of Kim, all of those who returned to Korea have passed away.

Kim was born in Deokgok-ri, Jinbuk-myeon, Changwon-gun, Gyeongsangnam Province in 1921, the youngest of four brothers and three sisters. In May 1942, at the age of 20, he passed a recruiting test to serve as a camp sentry to watch over the roughly 261 thousand Allied POWs that resulted from Japan’s thrust into Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. Since they knew they would eventually be conscripted into the war and because they wanted to try new experiences, in addition to a monthly wage of 50 yen per month for two years, some 3,223 colonized youth like Kim passed the test. For two months starting in June 1942, they underwent training at a temporary Japanese army boot camp in Seo-myeon, Busan (now the former location of Camp Hialeah), and on Aug. 19, 1942, they boarded a boat for Southeast Asia.

Kim was deployed to the Makassar Plantation on Java. There he was forced to watch over British, Australian and Dutch soldiers captured by the Japanese. With help from the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under the Japanese Imperialism, the Hankyoreh was able to obtain trial records written by a Dutch soldier of the Java war crimes court. We confirmed that Kim, then using the Japanese name Kanemura Tekki, was sentenced on May 4, 1948, to seven years in prison on charges of beating POWs with fists, a heavy bamboo club, the butt plate of a gun and sticks. Kim pleaded that there were four Kanemuras in his unit, and that he was just a cook, but the court did not accept this. His wife said that he said several times that he had struggled to survive. Some 148 Koreans were found guilty of war crimes like Kim, and of these, 129 (including 14 who were executed) were also POW camp guards like Kim.

After serving time for his prison sentence at Indonesia’s Tjipinang Prison, Kim was moved on Jan 23, 1950, to Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison, which housed war criminals. On Sept 12, 1950, he was released. What awaited those who were released was terrible hardship. Unable to endure the difficulties, two took their own lives. Those with a place to go in Japan stayed, but those with had no place to go chose to return to their homeland, then one of the poorest countries in the world, to endure a social cold shoulder for being “pro-Japanese.”

|

Kim Seok-ki, left, and his wife. Kim is the only convicted Class B/C war criminal still alive in Korea. (Hankyoreh) |

The war criminals that returned to Korea chose silence. Kim’s eldest daughter, 47, said she did not know until recently that her father was a war criminal. When she thinks about it, she sees that her father was a mysterious man. What really frightened her was his habit of sleeping with his eyes open. He would say things in his sleep like, “If you do not do it, you will die.” At the time, she did not know what he was talking about. One time, while they were living in Jinhae, a thief who broke into the house ran off after seeing her father sleeping with his eyes open.

Jeong, Kim’s wife, was an elite woman for the 1950s who graduated from Seongji Girl’s High School in Masan. Waiting for a good catch, she thought about several offers of marriage, and at the age of 25, rather late for marriage at that time, she met Kim through a relative. She received permission from her parents to marry him after he said he planned to return to Japan after getting married. Those plans did not work out, however, and life became a struggle. Jeong said he initially said they were nine years apart in age, but after their first child was born, she learned the difference was actually 15.

Having spent such a long time abroad, Kim could hardly speak Korean. As a result, he could not find a stable job. He supported his family by wandering from construction site to construction site. Only in the late 60s did he finally get a job with Daelim, but he retired in 1978. Kim’s son-in-law, Jang Gyeong-seong, said he did not know why his father-in-law could not return to Japan. He said, however, in light of Kim’s remarks that he had participated in a number of demonstrations, it seemed that the Japanese government may have considered him a radical wounded veteran.

Kim was a youth, just 21, when he left his homeland, and returned to Korea at age 39 after 19 years of bitter wandering. In 1962, the following year, he married and his eldest daughter was born. Now recognized as a victim of Japanese forced mobilization, he receives 800 thousand Won ($692 USD) per year from the government as a health subsidy. Kim’s wife said he still had a lot of unresolved anger. Long ago, Kim used to talk about how he suffered, but she did not listen closely to the circumstances of his suffering, and for this she was most sorry. Jeong said she sometimes cries even now, thinking about how miserable and pathetic the lives of she and her husband have been.

Traces of Forced Mobilization – Part Six – March 10, 2010

English / Korean / Japanese

Temple Death Registries in Japan Evidence of Conscripted Labor

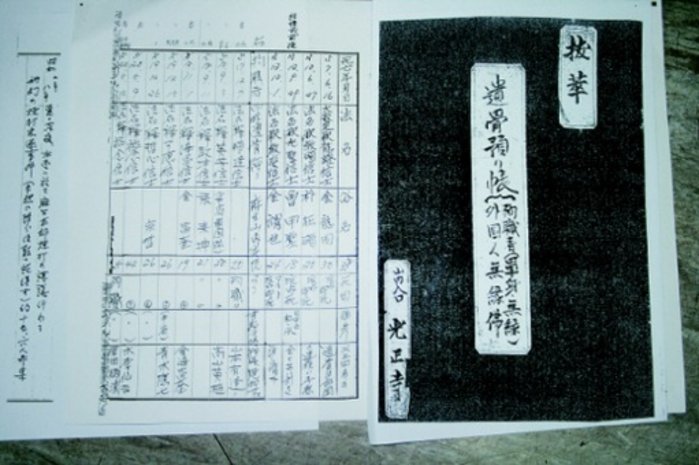

The registries are significant documents since the Japanese government and businesses destroyed or concealed related documents in the immediate wake of the nation’s defeat

Iizuka is the central city of the Chikuho region on the Japanese island of Kyushu. For decades from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, it prospered as a mining city, and it is home to the stately mansion of the Aso family. This structure may be seen as a glimpse into the time when three to four generations of former prime minister Aso Taro’s ancestors reigned as lords of the region, using the money they earned from mining development to expand their work into railroads, cement, banks and hospitals. The mansion was nearly burned down once by angry Korean workers.

The record of the workers’ arson plot against the Aso mansion lies not in a document from the Tokko, police officers that dealt with political offenders during the Japanese Empire, or from one of the Aso businesses, but in a temple document. At the entrance to the Sannai Mine, one of seven managed by the Aso family in the Chikuho area, is the Goshoji Temple. The reference to the arson plan was included in a Goshoji human remains interment document obtained by the Hankyoreh. It says, “Summer of Showa Year 7 (1932), conspiracy to commit arson against Aso residence was committed at night at the main temple.” This is followed by the words, “Arson uncompleted, around 15 to 16 individuals took part, head monk attempted to dissuade them beforehand.”

Did the arson plot really happen? The document’s writer was Fujioka Seijun, then the head monk. His record seems to fit the circumstances at the time. An economic depression had continued in the wake of the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929, and the cold winds hit the mines of Chikuho as well. Having previously withstood the conglomerate mining companies through low wages and subcontracting, the Aso family began closing some of its shafts and dismissing workers, starting with the elderly and Koreans. As the interests of the Japan Coal Miners’ Union, which was attempting to organize Korean workers, coincided with those of Korean miners who wanted improved treatment, a general strike took place in the Iizuka area in August 1932. Police, youth associations and officials in charge of Korean labor used violence to brutally repress the strike, but the Korean workers scattered to shrines and temples, where they continued the struggle for another three weeks.

The interment form included a long list of people who died in accidents at the mines and had no surviving family. They are listed according to the format of date of death, followed by legal name, real name, age, cause of death, and additional comments. The names of Koreans jump out on the list of victims. There are also cases where a Japanese name is written alongside, or where only a Japanese name is recorded. The ages range from the teens to the forties. Many causes of death are listed as ‘instantaneous death within the shaft’ or ‘died while on duty.’ The implication of ‘died while on duty’ is scarcely different from accidental death.

Noh Gap-seong, who died at the age of eighteen in a mining accident on Sept. 29, 1939, is the youngest person on the list, apart from some small children. A note next to his entry reads ‘eve of marriage.’ This seems to reflect the troubled emotions of Fujioka about the Korean bachelor from Baekgu Township in Gimje County in Korea, who suffered a tragic death just a day before his wedding. The real name of another Korean, who had been entered on the interment form only by his Japanese name and was affiliated with the Hokoku Tai labor corps, was uncovered through the efforts of Japanese civic groups and the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization Under the Japanese Imperialism. According to an investigation of newspaper reports and cremation approval forms, twenty-eight-year-old Choi Yeong-sik was born in Seosan, South Chungcheong Province, and met his tragic death on Sept. 3, 1943, while attempting to rescue a Japanese miner trapped by a cave-in.

|

The Goshoji human remains interment document. On the upper left side, there is a reference to the arson plot against the Aso family’s mansion. (Hankyoreh) |

The interment form contains numerous pieces of such information. Another temple document with more detailed information is the death register. This register, installed in every Japanese temple since the early 17th century, basically contains the Buddhist name, real name, date of death and age at death of the deceased. Depending on the temple, information such as cause of death, status, and lifetime activities may also be included, and there are also family records spanning several generations. In modern terms, it could be called a database of personal information. The reason death registers have such significance for determining the circumstances of conscription and verifying the deceased is because the Japanese government and businesses destroyed or concealed related documents in the immediate wake of the nation’s defeat. Some overseas Korean researchers in Japan like Kim Gwang-yeol have been traveling around the temples of Chikuho for decades asking the head monks to allow them to read the death registers. The painstakingly collected details have been published in a number of research papers.

Currently, however, reading the death registers is prohibited as a rule. The justification given for the strict prohibition is the protection of private lives, in light of Japanese discrimination against burakumin. This term is used to refer to the lowest class of the population, which was previously also called hinin, meaning ‘non-human.’ Reportedly, there were many instances in the past in which private detective agencies were commissioned to examine death registers in order to check family histories for new employees or prospective marriage partners.

The understanding of the relationship between the remains of Korean workers and the reading of death registers varies widely between orders and temples in Japan. Bridging that gap will require restoring communication and trust between Buddhist groups in both countries, but the reality is a different story. Experts unanimously state that there is not enough expression of interest at the order level or systematic activity, as interested monks in Korea generally pursue separate contacts.

Article – March 11, 2010

English / Korean / Japanese

Private Group Repatriates Remains of Korean Conscripted Laborers

More remains are expected to be repatriated in 2010, which marks the 100th anniversary of Japan’s forcible annexation of Korea

“I feel comfort in being able to bring home all of you who were so lonely there in a foreign land. May you rest in peace …”

Eighty-two-year-old Gu Yong-seo’s voice trembled as he stood before the small granite marker bearing the words “Burial Site for the Remains of Koreans in Japan without Surviving Relatives.” Gu is currently serving as an adviser for the Committee for the Repatriation of the Remains of Koreans in Shimizu, which formed in March of 2008 to repatriate the remains of 94 Koreans stored at the Enshrinement Hall for the Remains of Koreans in the city of Shimizu in Japan’s Shizuoka Prefecture.

The committee brought the remains back from Japan on March 8 and held a repatriation ceremony Wednesday morning at the National Mang-Hyang Cemetery in Cheonan, South Chungcheong Province. A party of twelve individuals from the committee, which is made up of leaders from the Shimizu chapters of the Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan) and the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon), placed a white chrysanthemum above the stone and observed a moment of silence. The edges of the grave were covered with the previous night’s fall of March snow.

Previously, three repatriations of the remains of soldiers and civilian military workers interred at the Yutenji Temple in Tokyo were carried out at the government level following the launch of the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization Under the Japanese Imperialism (Gangje) in 2005. But the March 8 repatriation marked the first time the remains of people believed to be company laborers were repatriated by a private group since the large-scale repatriation of remains in the 1970s and 1980s. The committee itself also paid the expenses, without any support from the South Korean government.

In the port city of Shimizu, where the remains had previously been kept, there were reportedly as many as 3,000 Korean workers at one point performing physical labor at sites such as shipyards and cargo bases. After the war, Inou, the head monk at the Kokai Temple in Shimizu’s Kitayabe area, collected the remains of Koreans who were spread out among 34 nearby temples and notified Koreans from the local community. When the temple was closed down in 1956, Chongryon’s Shimizu chapter petitioned city authorities to create an interment site for the remains. When the facilities became decrepit, the city of Shimizu respectfully accepted a May 1991 petition by Chongryon and Mindan and built a new interment site.

Seventy-two-year-old Haruda Michisaburo, who was serving as head of the Shimizu City Council at the time, said, “There were no voices of objection to building an interment site for those who died in a foreign country.” Haruda added, “I am happy that the hopes of all those people who have worked for decades to bring these people home have come to fruition.”

|

Members of Chongryon and Mindan hold a repatriation ceremony for the return of the remains of Korean conscripted laborers on March 10 at Mang-Hyang Cemetary, located along Mang-Hyang Hill (Nostalgia Hill) in Cheonan City, South Chungcheong Province. (Hankyoreh) |

The repatriation process was not simple, as it was essentially impossible to find any relatives of the deceased. Of the 94 individuals repatriated on Wednesday, twenty-nine, or less than a third, have been identified by name, while addresses, which provide the decisive clue for tracking down relatives, are extant for only ten of the deceased. Additional identity confirmation required the cooperation of the companies where the individuals worked, but the companies involved, including Nippon Kokan and Nippon Light Metal, refused to provide the information. In the end, the repatriation committee obtained the help of Gangje and was able to confirm the surviving family for two individuals, Lee Mal-sik (born in 1917) and Ra Gyeong-ho (born in 1911), but it was forced to give up tracking identities for the remaining 92.

For 2010, which marks the 100th anniversary of Japan’s forcible annexation of Korea, the South Korean government plans to pursue the repatriation of 219 deceased soldiers and civilian military workers currently stored at the Yutenji Temple in May, and of a currently confirmed 2,601 private workers in the latter half of the year. Jeong Hye-gyeong, director of Gangje’s second investigation bureau, said, “The Shimizu case is a meaningful instance in which Mindan, Chongnyon and a Japanese local government joined forces to bring about the repatriation of remains.”

Jeong added, “The government is also carrying out discussions with the Japanese government from various angles to enable the rapid repatriation of the remains of our ancestors who passed away after lives spent in suffering.”

Article – March 27, 2010

English / Korean / Japanese

Koreans Come Together to Memorialize Ahn Jung-geun

Participants from North Korea and South Korea to honor the 100-year anniversary of Ahn’s martyrdom

“Today we carry Ahn in our hearts. The hearts of 80 million Koreans, North and South, are Ahn’s tomb.”

On Friday, 100 years after Ahn Jung-geun met his death in an imperial Japanese execution ground, his ancestors from North Korea and South Korea put aside their tensions for a moment as they met for a memorial mass at a hotel in Dalian, where the former Lushun Prison was located. The Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Society, led by Father Ham Se-ung, and the Korean Council of Religionists from North Korea led by Chairperson Jang Jae-un, held the first North Korea-South Korea memorial ceremony after a long period of preparation.

The priests, including Ham, wore red vestments and lit a red candle on the altar, honoring Ahn as a martyr. In the last moment of his life as he was heading towards the execution grounds, Ahn read a will to his two brothers, mother and wife. “Even if I shall go to heaven, I will strive for Korea’s independence. If news of Korea’s independence reaches heaven, I shall dance and cry mansei in celebration.”

In his address, Ham said that while we cannot find Ahn’s body, what is important is that 80 million Koreans in North Korea and South Korea remember his spirit and meaning, live as he did and work so that they become a new generation of Ahn Jung-geuns. He prayed for unity and reconciliation between North Korea and South Korea. Jang Jae-un, the chairperson of the Korean Council of Religionists from North Korea, said a century ago, Ahn sacrificed his precious life as if it was a bit of straw to recover Korean independence, in order to recover the national sovereignty that was taken away by the invading Japanese imperialists, and build a prosperous country. He called on North Korea and South Korea to rise up and, like their joint commemoration of Ahn, overcome ideology and work for independent unification.

|

Father Ham Se-ung, Catholic priest of South Korea, left, and Jang Jae-un, chairperson of Korean Council of Religionists from North Korea shake hands in front of the bust statue of Ahn Jung-geun at Lushun Prison in China, March 26. (Hankyoreh) |

After this, the group headed to Lushun Prison, where Ahn was martyred. It was raining the entire day 100 years ago on Ahn’s last day, but today clear skies met the procession. At Lushun Prison, a South Korean parliamentary memorial team led by Lawmaker Park Jin and the Lushun Ahn Jung-geun Research Society and Dalian Catholic Church held ceremonies respectively.

An elderly woman dressed in a hanbok laid flowers sent from Korea in front of a statue of Ahn at the prison’s memorial for anti-Japanese martyrs. The woman was Shin Dong-suk, 81, the wife of the late Do Ye-jong, a unification activist who was unjustly executed during the Inhyeokdang Incident of 1975 under Park Jung-hee’s military dictatorship. She said she believed the spirits of Ahn, who died for Korean independence, and her husband, who died wishing for unification, were the same. Laying the flowers, she said she wishes for the Korean people to receive Ahn’s will and move forward with one heart, and that her late husband would also be with the people as well. Yang Yu-gyeong, who brought his three children along for the journey for the memorial ceremony, said he brought them because he wanted them to know Ahn’s spirit and history.

At the memorial hall on the execution grounds where Ahn was killed, the North Korean and South Korean participants sang “Our Wish is Unification.” North Korea’s Jang said he had visited several times before, but today was quite different because North Koreans and South Koreans were participating in the ceremony together. On this day, North Korea and South Korea became one in the spirit of Ahn.

Editorial – March 27, 2010

English / Korean / Japanese

Pursuing Martyr Ahn Jung-geun’s Wish for East Asian Peace

A variety of memorial events were held throughout the country and overseas yesterday to mark the 100th anniversary of the martyrdom of Ahn Jung-geun. In Seoul, a central memorial ceremony was held with Ahn’s descendants, Prime Minister Chung Un-chan and other government figures, and members of the Kwangbokhoe in attendance. Lushun Prison in China, where Ahn died, North Korea and South Korea held a joint memorial.

But even amid these many memorial events, it is difficult to suppress a sense of shame in one corner of the mind. Even today, one hundred years after Ahn was put to death for assassinating then-Japanese prime minister Hirobumi Ito, one of the key figures who masterminded Japan’s colonization of Korea, to achieve independence for the Korean people and peace in East Asia, we have been unable even to locate his remains. The government must work to prevent the people from suffering this shame any longer by working with Japan, which possesses records regarding Ahn, and China, where his remains are buried, to disinter and enshrine his remains as soon as possible.

It is also every bit as important that Ahn’s spirit be carried on. His heroic deeds were not simply intended for the independence of the Korean people. Behind his efforts in the independence movement against Japan, and his assassination of Ito Hirobumi, was an idea of peace, pursuing the equality and coexistence of humankind.

|

The Korean Army unveils a conference room for high-ranking officers under a new name, the Gen. Ahn Jung-geun (1879-1910) Main Conference Room, on March 25 at Army headquarters in Gyeryongdae, South Chungcheong. (JoongAng Daily/Cho Yong-chul) |

In his essay “On Peace in East Asia,” Ahn precisely pinpointed the problems spawned by imperialist competition, writing, “In today’s world, East and West are divided, the races are all different, and we compete as a matter of course, as we train youths and push them out into the battlefield, and countless precious lives are abandoned like sacrificial objects, the blood becomes a flowing stream and the corpses form mountains.” He explained that at this time of sorrow with Western occupation of the East, the “best measure would be for Eastern people to unite as one for defense.” But because Japan ignored this trend and instead planned its own imperialist aggression against China and Korea, he assassinated Ito out of the judgment that there was no choice but to start a “righteous war for Eastern peace.”

Ahn’s view of peace in East Asia shines even brighter in the reality of today a century later. Capitalist competition has become more extreme, and the division of the Korean people, which has lasted for more than half a century, is threatening peace in East Asia. The recent rise in calls for a “Northeast Asian community” bears some connection with this situation. In that sense, it is undesirable to refer to Ahn as a general, which the Defense Ministry has tried to call him, since it may appear to drag the meaning of his deeds for Eastern peace down to the level of mere nationalism. The most important thing in the praise of Ahn Jung-geun is to carry on his convictions regarding peace.

The above articles appeared in The Hankyoreh on the respective dates indicated in February and March, 2010. William Underwood’s introduction was written for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Posted at The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus on April 26, 2010.

Recommended citation: The Hankyoreh and William Underwood, “Recent Developments in Korean-Japanese Historical Reconciliation,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 17-3-10, April 26, 2010.

See also:

Kim Hyo Soon and Kil Yun Hyung, “Remembering and Redressing the Forced Mobilization of Korean Laborers by Imperial Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 7-3-10, February 15, 2010.

Kang Jian, Arimitsu Ken and William Underwood, Assessing the Nishimatsu Corporate Approach to Redressing Chinese Forced Labor in Wartime Japan

William Underwood, New Era for Japan-Korea History Issues: Forced Labor Redress Efforts Begin to Bear Fruit