|

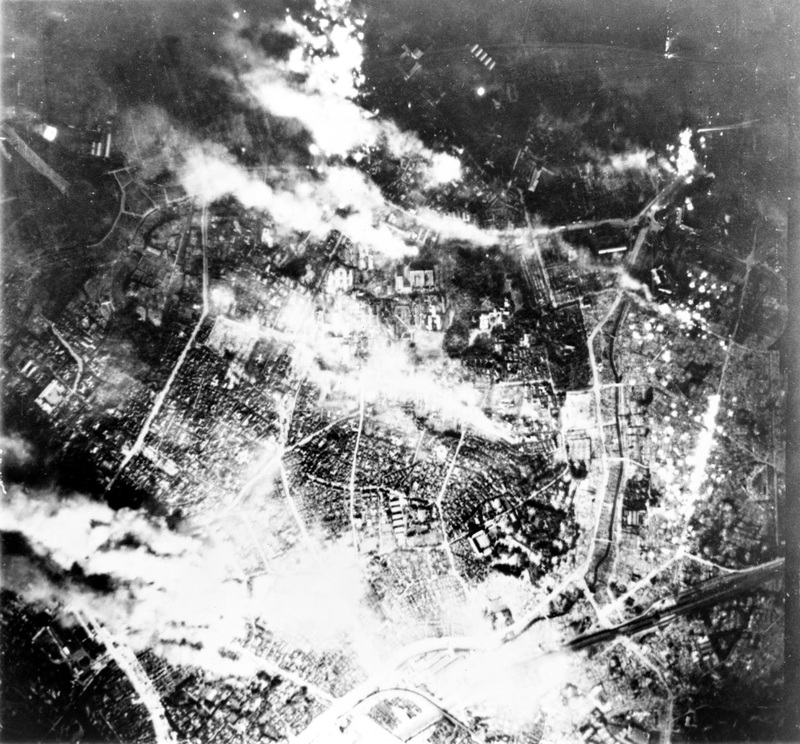

Tokyo in flames following the B-29 firebombing raid, May 25-26, 1945 |

May 25th is the 70th anniversary of the Great Yamanote Air Raid. This was the fifth and final low-altitude night incendiary raid on urban areas of Tokyo by the US Army Air Forces. The first of these five massive firebombing raids was the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10, 1945. On that night, 279 B-29s dropped 1,665 tons of incendiaries on the Shitamachi district of the capital. By dawn, more than 100,000 people were dead, over a million were homeless, and 15.8 square miles of Tokyo had been burned to the ground.

The number of bombers and incendiaries used in the final firebombing raid far exceeded those on March 10. On the night of May 25-26, 464 B-29s dropped 3,258 tons of incendiaries on the Yamanote district in the heart of Tokyo. 3,242 people were killed, 559,683 people were made homeless, and 16.8 square miles of Tokyo were incinerated. The area burned out that night was one square mile more than that of the devastating March 10 firebombing raid. After the Great Yamanote Air Raid, a total of 56.8 square miles of Tokyo had been destroyed. There were no “strategic targets” left.

The death toll of 3,242 people seems very low compared with the more than 100,000 who perished in the Shitamachi firebombing. In many places, the hilly topography of the Yamanote district slowed the progress of the fires, while the open spaces made it much easier for people to escape. In one place, however, the fires burned with a speed and intensity as great as any of those on March 10.

Those who are familiar with Tokyo may be surprised to learn that this place was the Omotesando, the splendid tree-lined avenue stretching from Aoyama-dori to the entrance to Meiji Shrine. Often referred to as the “Champs-Élysées of Tokyo,” the Omotesando is famous for its fashionable boutiques and popular restaurants. The 30-meter wide avenue was completed in 1920 as the frontal approach to the Meiji Shrine. The magnificent stone lanterns that remain on each side of the entrance to the street testify to its original purpose.

|

The Omotesando as it looks today |

On the night of May 25-26, the B-29s poured incendiary bombs over the whole surrounding area, turning it into a sea of fire. The tall zelkova trees on both sides of the Omotesando and the elevated buildings behind them created a wind-tunnel effect that generated a firestorm of terrifying speed and intensity. Of the 201 trees lining the avenue, only 10 survived the inferno. The zelkova trees on today’s Omotesando were planted three years after the end of the war.

The following morning, charred bodies lay strewn along the whole length of the Omotesando (about one kilometer). Those who witnessed the scene near the Jingumae crossroads at Aoyama-dori would never forget it. Countless corpses were piled on top of each other at the entrance to the subway station and in front of the nearby Yasuda Bank (now Mizuho Bank). According to several witnesses, black stains left by the oil from these bodies remained on the wall of the bank and the pavement for a long time afterwards. The damage caused by falling incendiaries to the stone lantern on that side of the road is still visible at its base.

Although hundreds of people died in the inferno on the Omotesando in the early hours of May 26, 1945, it took 63 years for a memorial to the dead to be erected. This was thanks to the efforts of a group of local citizens who submitted a petition to Minato ward in 2005. The memorial stone is located on the pavement a few meters from Mizuho Bank. Its inscription reads as follows:

Praying for Peace

In May 1945, towards the end of the Pacific War, the great Yamanote air raid reduced most of the Akasaka and Aoyama districts to ashes. The zelkova trees on the Omotesando burned and many people, with no place to escape to, perished in a firestorm near the crossroads at Aoyama-dori. While consoling the spirits of those who died, we pray with all our heart for a peaceful world without war.

|

Memorial to the victims of the Great Yamanote Air Raid outside Mizuho Bank at the Jingumae (Omotesando) crossroads |

The following remarkable account of the inferno on the Omotesando was published in 1973 in Volume 2 of the Tokyo Air Raid Damage Records. Among the 150 accounts of the May 25-26 air raid in that volume, it is the only detailed record of what actually happened at the Jingumae crossroads. A thrilling description of a miraculous escape, it is also eloquent testimony to the plight of ordinary civilians in Tokyo who were caught between the iron grip of military authorities that cared little for their lives or property and the relentless firebombing campaign conducted by the US Army Air Forces.

Escaping by Bicycle

Kanayama Misao, national railway worker, 24

At the time of the air raid, I was living in a bungalow in Harajuku with four fellow national railway engineers – Nakazato, Terakado, Nakamura and Okuda. In our mid-twenties, we were full of energy and got on very well. In the evenings we took turns to prepare dinner on a kerosene cooking stove. The almost daily air raids were steadily reducing Tokyo to ashes, but our high spirits helped to dispel the gloom.

Usually three of us were at home while the other two worked on night duty, but on the night of May 25 it was just Nakamura and me. We heard the familiar wail of the air-raid alert siren at around 10.00 p.m., followed by a radio announcement: “Enemy formations approaching the mainland over the sea from the south.” Now that there was hardly anywhere left in Tokyo to burn, we had an unpleasant feeling they were coming for us tonight. We still had time to get ready before they arrived, so we packed the futons and filled our rucksacks with food and other essentials. We put on coats over our railway uniforms and attached our pocket watches – an engineer’s most prized possession – to our trousers. Then we strapped our steel helmets to our backs, put on our gaiters, tied gas masks to our shoulders with cord, and filled the buckets with water. Our preparations were complete. At around that time, the air-raid warning sounded. They had come at last!

We went outside to look. Beams of light from searchlights were probing the sky for enemy planes. Illuminated by the searchlights, they were coming in lower than ever before. I was used to seeing B-29s flying high above the clouds, but I didn’t feel afraid unless they were directly overhead. Tonight was different. With their silver wings and glistening bodies, they even looked beautiful. Anti-aircraft shells flashed as they exploded in the air. About ten B-29s flew over, then twenty, then another ten. There was no end to them. The rotating searchlights picked them up one after another, as if counting them.

Incendiary bombs started raining down over the nearby Meguro district. Falling like red shooting stars, they suddenly burst into flames. Small at first, the flames expanded as they fell until they were like giant sparklers. Wherever they dropped, the ground turned bright red and pillars of flame shot up. Although they were not yet above us, the sky was filled with sounds of explosions, anti-aircraft fire, and the bombers’ engines. The flames were still in the distance, yet it seemed like we were gradually being surrounded. Each B-29 seemed to have its own target.

I knew we would be in great danger unless we escaped quickly from that ring of fire, but I kept this thought to myself. Apart from children and old people, both men and women were expected to stay put and fight the fires. Those who ran were likely to be called traitors. Since I thought the same way, I hesitated to suggest escaping, even to a good friend like Nakamura. “Look! There’s a Gekko night fighter!” he shouted, pointing up at the sky. I saw red bullets streaming into the fuselage of a B-29 that had just dropped its load and was flying up diagonally away from us. The accuracy of this burst of machine-gun fire and its beautiful color made a pretty picture. Moments later, a flame appeared on the enemy plane’s fuselage and gradually grew larger. “They’ve got one over there too!” cried one of our neighbors. There were quite a few Japanese planes up there firing at the B-29s. So these were Japan’s famous night fighters! I had never seen them put up such fierce resistance.

Suddenly we heard an explosion nearby, a strange scraping sound like someone sweeping sand. I looked round and saw a huge red ball of fire falling from the sky. “Incendiary bombs! Look out!” I screamed and ducked behind a telegraph pole. As they came down, they sounded like hundreds of empty cans rolling on the ground. The upper floor about five houses down the road was on fire. I took a bucket of water and ran up the stairs of the burning house. The eight-tatami mat room was already filled with flames. Stuck to the tatami like melted rubber, an incendiary stick was spitting out fire. This wasn’t something I could put out with a single bucket of water. Shouting “Get the pump!” I jumped back out of the room, but I’d forgotten I was on the second floor and tumbled backwards down the stairs. It was a shock but I didn’t feel any pain.

“Nakamura, get the pump!” I shouted again, but now four or five neighbors were outside the house with the hand pump. Holding the tip of the hose I climbed back up to the second floor, but it was already engulfed in flames. The house had been hit by two or three incendiary bombs and the fires were unstoppable. Even so, we carried on spraying water at the ceiling from the first floor, clinging to the central beam when more bombs fell and turning the hose on ourselves when the heat became unbearable. The fires soon filled the second-floor room and started to spread outside from the eaves. The water pressure in the hose weakened. Nakamura called up to me, “Kanayama, it’s no use. Everyone’s gone. Let’s get out of here!” I threw down the hose and ran outside. The surrounding houses were in flames and some were on the verge of burning down. The people who had been carrying the pump were now taking futons out of their houses and soaking them with water. Incendiaries continued to rain down and the fires had whipped up a fierce wind.

Nakamura and I ran back to our bungalow. Miraculously it was not yet on fire. There was no time to lose. “We’ve got to bury the food,” I said. We dug a hole in a corner of the garden and threw rice, soybeans, and canned foods into it. Then we took out the futons and put them down next to the bicycle. At that moment there was an explosion like a hundred claps of thunder as countless incendiary sticks burst out from their parent bomb.

The sounds of explosions, falling firebombs, and burning houses mingled with a howling wind that blew smoke in our eyes. Now the eight-mat room at the back of our bungalow was on fire. An incendiary bomb had fallen in through the roof. We picked up buckets and were just about to go in when there was a deafening explosion, a white flash and a rush of wind. We both shouted “Get down!” and threw ourselves into the drainage ditch at our feet. I heard a scream. A torrent of incendiaries had fallen all around us. Someone was crying for help but we couldn’t even look round. I was pressing my face so hard against the bottom of the ditch that it hurt. I felt dizzy and my throat was dry. Sweat was streaming down my back. About two meters away from us, globs of flame were shooting out of an incendiary stick. It was like something from another world. “Damned if I’m going to die like this!” I muttered to myself.

Suddenly everything went quiet. We pricked up our ears. We weren’t imagining it – the bombing had ended. There was no time to lose. We loaded the futons onto the bicycle and set off, Nakamura at the front and me pushing from behind. First we made for the more open space of the Omotesando road leading to Meiji Shrine. Looking around as we ran, I noticed that nobody else was escaping carrying futons or other belongings. We came across a group of men who were still madly dashing about with buckets of water. For a moment I felt ashamed that we were running away. As we turned the first corner at great speed, one of them jeered, “Escaping, are you?” and three of them started walking purposefully in our direction. “Run for it!” I shouted and we both got behind the bicycle and ran for all we were worth. They threw the water in their buckets over our heads, drenching both of us. “You scum!” we heard them shouting behind us, but we didn’t look back. It was strange. A moment earlier I had felt guilty that we were escaping while they risked their lives, but now those feelings had gone.

We still had about 150 meters to go to the Omotesando road. The smoke was getting thicker and pieces of wood and tinplate were flying about in the wind. But the road we thought would be safe was full of sparks whipped up by the wind and smoke swirling under the roadside trees. It was crowded with people like us who had given up trying to fight the fires. In the howling wind, we heard the muffled sound of explosions. They had started bombing again. Looking up in the direction of Meiji Shrine, we saw a whirlwind of flames at the bottom of the hill and sparks dancing in the air behind it. “This is hopeless. We can’t go to the shrine now. Look, they’re all coming back from there,” I said to Nakamura. “It’s no good going down there, is it?” I asked a woman passing nearby. “The people trying to get through to the shrine got caught in the fires,” she replied. We gave up on Meiji Shrine and decided to make for Aoyama instead. Someone in the returning crowds shouted, “We must get to Aoyama Cemetery! It’s the only place left.” We weren’t sure about it, but decided to join the flow of people making for the cemetery. Once people join a group and start walking together, they seem to behave quite strangely. Everyone becomes obsessed with not falling behind and walks faster and faster. Without time to look up at the sky any more, we cast in our lot with the fickle crowd.

As we were approaching the Jingumae crossroads, the whole area lit up as if the sun had come out. Torrents of incendiaries were falling and bursting into flames as they hit the ground. We got behind a telegraph pole for cover. Four or five people were clinging to each pole. The road filled with smoke and a foul smell. When we returned to our senses and looked around, several people were lying on the road, but it was all we could do to save ourselves. At the sound of explosions or falling incendiaries, people crouched on the ground, hugged telegraph poles, or cowered behind others. Even then they hung on to their belongings or carried on pulling their handcarts as they continued the desperate rush to Aoyama Cemetery. Everyone seemed to think they would be safe if they could get to the graveyard. Nakamura and I were still pushing the bicycle with our futons on it. Each time we crouched down on the ground we pushed it aside, then picked it up again and continued on our way. It may seem ironic that people trying to stay alive were escaping to a place for the dead, but in no time the road to the cemetery was full of people. Although fires were already burning on both sides of the road, they seemed oblivious and walked around or stepped over bodies on the ground without apparent concern. We must have been walking through the flames, smoke and hot wind for about five minutes when the people at the front came to a sudden halt. Soon they had turned round and were coming back towards us. In their shock, people around us cried out and tried to stem the reverse flow. Somebody shouted, “Aoyama Cemetery is a sea of fire!”

What were we to do? When the returning crowd got back to the Jingumae crossroads, we collided with another stream of people who had fled up the road from Shibuya Bridge, forming a swirling mass of humanity in front of Jingumae subway station. By now we all knew we were in mortal danger. Amid the explosions, fierce wind and raging flames, everything burnable was starting to catch fire. Hundreds of people were swarming around more and more frantically. Should we stay with them or try to break away? For the time being, we let ourselves be pulled along by the crowd.

Even in those days, the Omotesando was a modern road about thirty meters wide. On the right in the direction of Meiji Shrine were the Aoyama Dojunkai Apartments, a large ferroconcrete apartment complex. On the left, above the stone wall, stood the imposing houses of wealthy residents, looking down contemptuously on the common people below. Starting about 100 meters from the Jingumae crossroads in the direction of the shrine was the steep hill descending to the Shibuya River. Once fires had started along the roadside, the high buildings on both sides formed a tunnel that drew up the wind from the bottom of the hill and stoked the fires. Whipped by the wind, the flames multiplied to create an inferno across the whole road. These fires blocked the path of the people trying to escape along the Omotesando road to the woods around Meiji Shrine. Some still tried to break through to the other side, but they were swallowed up in the raging flames before our eyes.

The smoke was so thick that we could no longer see our feet. It was getting harder to breathe and we had to stop many times to clear our throats. My cheeks were scorched and stinging. The man walking next to me suddenly lurched forwards and sank to the ground. The smoke found its way through the wet towel over my face, getting into my eyes and throat. People were collapsing all around me. I was no longer aware of the sound of bombing or flames from the incendiaries, only my immediate surroundings.

Somehow we managed to extricate ourselves from the crowd and stagger across to the side of the road under the trees where we had left the bicycle. We slumped down on the ground next to it. Now it was hard to see the crowds through the smoke. I could hardly breathe and was starting to feel dizzy and confused. Was I going to burn to death? Tears rolled down my cheeks as I thought how my mother and father, elder brother and his wife would have no idea I was in this plight. I saw the faces of my parents in the countryside, my brother and his wife smiling, my little niece playing. Then came the happy childhood memories, as if they were passing before my eyes. I saw the smiling face of my wife, who had gone to stay with my folks. She seemed to be saying something. I remember thinking it odd that dying should feel so pleasant and peaceful.

With a start, I realized that Nakamura was gripping my hand and speaking to me. I don’t know what I said in reply but I remember reaching out and grabbing something on his back. I tried to shout, “The gas masks! Nakamura, the gas masks!” The words didn’t come out, but Nakamura understood from my gestures. With our last ounces of strength, we put on our gas masks and slumped down on our backs facing upwards. We must have been on the verge of suffocating. I don’t know how long we lay there, but at some point I became aware I was breathing. Groping with our hands, we edged further to the side of the road. We did not catch fire thanks to our thick overcoats which we had earlier soaked with water. Remembering the gas masks at the last moment had saved our lives.

By now the raging fires were consuming the roadside trees and telegraph poles. Not only the buildings but also the empty spaces between them had turned into a sheet of fire, and every time the sheet swirled round the number of bodies on the road increased. I thought hell must be something like this. Many people were running without noticing that their clothes were on fire. From the side of the road, we could only see their blurred shapes through our gas masks. We were breathing more easily now, but the shadow of death was approaching. Sparks were blowing over us and entering through the gaps in the towels around our necks. It was too hot to stay there, but where could we go? We pulled aside our gas masks and spoke quickly.

“What should we do, Nakamura? We’ll die if we stay here.”

“There’s no way out. We can’t escape these fires.”

“Don’t panic. If we panic, we’re dead.”

As we were desperately thinking how to escape, we noticed that the futons next to the bicycle were on fire. We pulled the bicycle away and got to our feet. Now we needed to make a life-or-death decision. Nakamura pulled aside his gas mask again and said, “Kanayama, we’ve got to go for the shrine. There’s nowhere else.” “But how can we get through the fires?” I had almost given up hope, but I wanted to live. I had an idea: “How about both of us riding the bicycle with the wet coats over our heads?” “Okay. I’ll get on at the front and you sit on the rack and hold down my coat. We can freewheel down the hill to the Shibuya River and jump in! If we don’t make it to the river, that’s too bad.” “All right, let’s go!” I replied. Even this brief exchange was hard for us. We were pulling aside our gas masks and wildly gesturing through fits of coughing. But we were desperate to survive. First we splashed water from a nearby cistern over our coats and caps and thoroughly soaked ourselves, then I got onto the rack and covered us with the coats. Nakamura held the handlebar and pedaled out into the middle of the road. We set off with a sinking feeling and were prepared for the worst. The bicycle quickly picked up speed. I couldn’t see anything, but felt the fierce wind beating against the coat on top of me. As we sped along, we were enveloped in smoke and flames. The heat was becoming unbearable. From time to time I felt us bumping hard against a moving object. We seemed to be hitting other people trying to flee from the fires. I silently begged their forgiveness, but there was no way we could stop now. We were breaking through the wall of fire. Just a little further!

I raised my head from Nakamura’s back and looked out from under the coat. At that moment, a burning house above the stone wall on the left started to collapse into the road in front of us. “Look out!” I cried as we slammed into something and the bicycle rolled onto its side. I have no recollection how we managed to escape from under the debris. The next thing I knew we were rolling in the Shibuya River putting out the fires on our clothes. Then we just sat in a daze in the shallow water until we recovered our senses. I had painful burns on my ears and nose. Both Nakamura’s hands were badly burned from holding onto the handlebars. We saw several people splashing through the water, beating out the flames on their clothes. But even the river was not safe – burning planks and timber were falling in from both sides. We had to get to the woods around Meiji Shrine.

Shaking off the urge to fall asleep in the river, we crawled up the bank and staggered along the road towards the shrine. To get to the entrance we had to cross Jingubashi Bridge over the Yamanote railway line. The whole area behind the bridge was now a raging inferno and on the other side where the shrine stood the air was full of swirling smoke. All we could see were the rails of the railway line glistening in the dark. We crossed the bridge and ran into the woods beyond. We’d made it! Exhausted, we slumped down at the foot of a tree. It seemed like a dream that we were here. Everywhere we looked, the surrounding area was enveloped in fire and smoke. The spacious Yoyogi parade ground was burning brightly, and even among the dense trees surrounding the shrine the tips of flames were visible.

Now we realized how meticulously the Americans had planned their cruel bombing strategy. Knowing that the only places of escape were the Aoyama Cemetery, the Yoyogi parade ground, and the woods around Meiji Shrine, they created a sea of fire. Now the woods were the only refuge left, but surprisingly few people had made it this far. It wasn’t just that we couldn’t see them for the trees and smoke. It seemed that the only people around were old folks and children who must have come straight here when the air-raid alert sounded, or who were fortunate enough to live nearby.

Smoke hung thick over the woods but it wasn’t suffocating. When we took off our gas masks, the air smelled sweet. Overjoyed to be alive, we felt weak at the knees. But what if the enemy firebombed the woods? Stray incendiaries had already fallen nearby and the fires outside might spread to the trees at any moment. Mostly elderly women and children, the other people we saw were cowering in fear around the trees near the shrine entrance. We had to go deeper into the woods. Our close brush with death had left both of us in a very agitated state. We got to our feet and Nakamura strode into the woods. I was just about to follow him when I heard a voice behind me crying “Uncle, help us!” Two little girls ran up to me, each grasping an arm. They were from our neighborhood, though I’ve forgotten their names now. Even at a time when so many children and old people were being forced to evacuate from the capital, here were two girls of about seven together with two elderly women in their sixties. I recalled that they were from a big family, and perhaps for that reason they had an unusually large air-raid shelter in their garden. The parents were in their mid-forties. When the girls grabbed my arms, I turned round and saw the two old ladies standing there looking at me, bleary eyed and exhausted. The wise parents must have told them all to go to the shrine when the air-raid alert sounded.

This put us in terrible dilemma. Nakamura and I had managed to escape from the raging fires thanks to our youth, the spiritual strength forged through our military training, our strong teamwork, and a fair amount of good fortune. We had fought desperately to survive, abandoning others along the way. If it were just the two of us, I felt sure we would somehow make it out of there alive even if the woods came under direct attack. If that happened, with two little girls and a couple of old ladies to look after, we wouldn’t have a chance. Should we take them with us? Surely it would be better to pull my hands away and follow Nakamura into the woods to ensure that we survived. But how could I abandon them? My legs started trembling as the inner struggle continued. As if sensing my indecision, the little girls looked up at me imploringly, their eyes shining under their air-raid hoods. The old ladies were staggering along beside them, each holding one of the girls’ hands.

Now Nakamura was coming back. He gave a start when he saw the five of us but when he got close he stood silently looking me in the eye. Was he trying to read my mind or did he feel as torn as I did? We stood there looking at each other for a while. Finally, without saying a word, Nakamura took one of the girls from me and held out his other hand to one of the old ladies. As we hurried into the woods, I thought to myself: “We’d certainly have a much better chance of surviving just by ourselves, but we couldn’t just abandon these little girls. They’ve been looking after the exhausted old ladies, but we are men! If we die because of it, so be it. We will have no regrets.”

Holding hands, the six of us ran from tree to tree in the spacious woods around the shrine, hiding in the undergrowth and cowering under an embankment until morning came. We saw a piece of wreckage of a B-29 stuck in the trunk of a large tree. It felt as if the lost occult powers of Meiji Shrine still lay deep in these woods hidden from the burning skies, but this was no time for such thoughts. There was one sight I will never forget. Separate from the groups of people escaping through the woods, as if trying to avoid them, I saw two people running from tree to tree – an army officer in uniform and a woman who appeared to be his newly-wed wife. Against the dark backdrop of the woods, the collar ensign of a military man who had lost his authority, the woman’s kimono and the white towel covering her face left an indelible impression on me.

Dawn finally broke. Running from place to place in the dark woods, we had lost all track of time. Everything was quiet now. They had not firebombed the woods around the shrine after all. Relieved but exhausted, the six of us slumped down against a nearby embankment. How long did we lie there? Eventually we came to our senses and got to our feet. Water was trickling from a severed water pipe nearby, forming a puddle on the ground. I soaked my hand towel in the water and wiped the bloodshot eyes of the children and old women. The little girls suddenly seemed lovable. I cupped their heads in my hands and said, “We’ve made it!”, and they smiled for the first time. I shuddered as I recalled how we might have abandoned them. According to my watch it was eight in the morning. What had happened to their parents during the night? We hoped they had escaped from the fires, but we couldn’t be sure. We had to go back and find out what had become of them and our neighborhood. Taking the children’s hands again, we left the woods and crossed Jingubashi Bridge.

The whole of Shibuya had been reduced to burnt-out ruins. A shroud of thin white smoke and the distinctive smell of burned flesh hung in the air. People with blackened faces and bloodshot eyes stood in the ruins staring into space. Filled with anger, sadness and despair, they staggered about gazing at what remained of the neighborhood where they had lived until the night before. But there were very few of them, perhaps thirty at most. What had become of all the people who were here last night?

Then we saw them. Beside the blackened telegraph poles and burnt debris of wooden houses, charred corpses were lying in the road. Near the Shibuya River were a dozen or so bodies that looked more like burned logs. Their hair and clothes had been completely burned off and their faces were like used charcoal. Soon there were so many bodies at our feet that we had to take care not to tread on them. Among them were the corpses of three mothers still holding their children. Another was lying face upwards with the charred remains of a newborn baby between her legs. She must have given birth in agony amid the flames and smoke. Was her husband away fighting at the front? How helpless she must have been, all alone and with nowhere to evacuate to. For the sakes of their husbands and their children, these mothers must have prayed for peace more fervently than anyone. At the feet of trees, at the roadside, and in the middle of the road, the whole width of the Omotesando was covered with hundreds of bodies. Some were charred black, barely retaining their original form. Others were intact, but their hair and clothes had been burned off and they were swollen to twice their normal size.

We reached the turning to the street where we lived. What had happened to all those people around the Jingumae crossroads? We left the children at the roadside and went to look. To our horror, we found countless bodies piled up on top of each other in front of the entrance of the subway station. Resembling black logs or sticks of charcoal, most of them were no longer recognizable as human beings. To whom could we protest about this barbaric atrocity? How cruel war is! It is always the people at the bottom who pay the ultimate price. At around noon a military truck would come to pick up this heap of charred corpses and carry them to Ueno Park. Knowing how close we had come to being among them, Nakamura and I just stood silently and stared.

After a while, Nakamura said, “Kanayama, we’ve got to go back to our neighborhood.” With the little strength we had left, we trudged away. Then we saw her: a woman walking among the charred corpses. One by one, she was covering the bodies with tinplate or pieces of board from the debris. Most of the dead were women. The faces of those who had died of asphyxiation were pale, as if they were just sleeping. Some of them had had all their clothes burned off but were otherwise unmarked. The haggard survivors were in no state to show curiosity in these bodies, but this woman could not bear to leave them exposed. She walked from body to body, covering each one, women and men. She looked like someone from our neighborhood – the wife of the doctor next door? We stood for a while and watched this guardian angel as she went about her work.

We entered the narrow side street from which we had escaped the night before. All we could see was burnt-out ruins. What had happened to those men who poured water over us? We went to the place where we had last seen them. The three men were lying dead on the ground, their bodies scorched red. They had apparently been hit directly by incendiary bombs. I no longer felt any resentment towards them. With tears streaming down my face, I muttered “You idiots! Why didn’t you escape? If you had, you might have survived.” We put our hands together in prayer and went on our way.

When we reached our neighborhood, the two little girls and their parents came running up to us through the ruins. Their mother and father had survived! All thoughts of the desperate struggle of the previous night evaporated with that happy reunion. The children were clinging to our legs like puppies. Seeing how happy they were to be alive, Nakamura and I smiled at each other through our tears.

On the road to the shrine, the housewife from our neighborhood continued to cover the bodies of the dead. May all those hundreds of souls rest in peace.

Richard Sams is a professional translator living in Tokyo. Since translating The Great Tokyo Air Raid a year ago, he has been researching the Tokyo air raids. His article on US bombing strategy appeared in the Japanese journal Kushu Tsushin (Air Raid Report). He is currently editing a book (“Voices from the Ashes”) with Cary Karacas on the firebombing of Tokyo from the viewpoint of the victims. He has an M.A. in history from Cambridge University.

Recommended citation, Richard Sams, “Inferno on the Omotesando: The Great Yamanote Air Raid”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 21, No. 1, May 25, 2015.

Related articles

• Richard Sams, Saotome Katsumoto and the Firebombing of Tokyo: Introducing The Great Tokyo Air Raid

• Robert Jacobs, The Radiation That Makes People Invisible: A Global Hibakusha Perspective

• Bret Fisk and Cary Karacas, The Firebombing of Tokyo and Its Legacy: Introduction

• Robert Jacobs, 24 Hours After Hiroshima: National Geographic Channel Takes Up the Bomb

• Asahi Shimbun, The Great Tokyo Air Raid and the Bombing of Civilians in World War II

• Yuki Tanaka and Richard Falk, The Atomic Bombing, The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and the Shimoda Case: Lessons for Anti-Nuclear Legal Movements

• Marilyn B. Young, Bombing Civilians: An American Tradition

• Mark Selden, A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq

• Yuki Tanaka, Indiscriminate Bombing and the Enola Gay Legacy