A My Lai a Month: How the

Nick Turse

A helicopter gunship pulls out of an attack in the Mekong Delta during Speedy Express, January 1969. AP/MCINERNEY

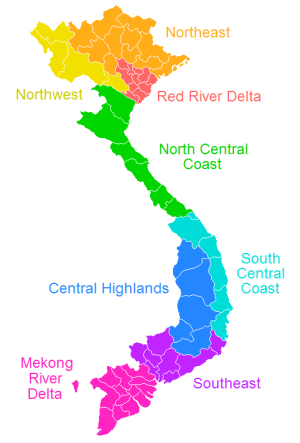

By the mid-1960s, the Mekong Delta, with its verdant paddies and canal-side hamlets, was the rice bowl of

Vietnam Regions

Yet in late 1968, as peace talks in

In late 1969 Seymour Hersh broke the story of the 1968 My Lai massacre, during which

Mylai victims

I uncovered that letter and two others, each unsigned or signed only “Concerned Sergeant,” in the National Archives in 2002, in a collection of files about the sergeant’s case that had been declassified but forgotten, launching what became a years-long investigation. Records show that his allegations–of helicopter gunships mowing down noncombatants, of airstrikes on villages, of farmers gunned down in their fields while commanders pressed relentlessly for high body counts–were a source of high-level concern.

A review of the letter by a Pentagon expert found his claims to be extremely plausible, and military officials tentatively identified the letter writer as George Lewis, a Purple Heart recipient who served with the Ninth Division in the Delta from June 1968 through May 1969. Yet there is no record that investigators ever contacted him. Now, through my own investigation–using material from four major collections of archival and personal papers, including confidential letters, accounts of secret Pentagon briefings, unpublished interviews with Vietnamese survivors and military officials conducted in the 1970s by Newsweek reporters, as well as fresh interviews with Ninth Division officers and enlisted personnel–I have been able to corroborate the sergeant’s horrific claims. The investigation paints a disturbing picture of civilian slaughter on a scale that indeed dwarfs

The Mekong Delta, the rice basket of

The Concerned Sergeant

An inkling that something terrible had taken place in the Mekong Delta appeared in a most unlikely source–a formerly confidential September 1969 Senior Officer Debriefing Report by none other than the commander of the Ninth Division, then Maj. Gen. Julian Ewell, who came to be known inside the military as “the Butcher of the Delta” because of his single-minded fixation on body count. In the report, copies of which were sent to Westmoreland’s office and to other high-ranking officials, Ewell candidly noted that while the Ninth Division stressed the “discriminate and selective use of firepower,” in some areas of the Delta “where this emphasis wasn’t applied or wasn’t feasible, the countryside looked like the Verdun battlefields,” the site of a notoriously bloody World War I battle.

Col. David Hackworth briefs Gen. Julian Ewell (right)

That December, a document produced by the National Liberation Front sharpened the picture. It reported that between December 1, 1968, and April 1, 1969, primarily in the Delta provinces of Kien Hoa and Dinh Tuong, the “9th Division launched an ‘express raid'” and “mopped up many areas, slaughtering 3,000 people, mostly old folks, women and children, and destroying thousands of houses, hundreds of hectares of fields and orchards.” But like most NLF reports of civilian atrocities, this one was almost certainly dismissed as propaganda by US officials. A United Press International report that same month, in which

Then, in May 1970, the Concerned Sergeant’s ten-page letter arrived in Westmoreland’s office, charging that he had “information about things as bad as My Lay” and laying out, in detail, the human cost of Operation Speedy Express.

In that first letter, the sergeant wrote not of a handful of massacres but of official command policies that had led to the killings of thousands of innocents:

Sir, the 9th Division did nothing to prevent the killing, and by pushing the body the count so hard, we were “told” to kill many times more Vietnamese than at My Lay, and very few per cents of them did we know were enemy….

In case you don’t think I mean lots of Vietnamese got killed this way, I can give you some idea how many. A batalion would kill maybe 15 to 20 a day. With 4 batalions in the Brigade that would be maybe 40 to 50 a day or 1200 to 1500 a month, easy. (One batalion claimed almost 1000 body counts one month!) If I am only 10% right, and believe me its lots more, then I am trying to tell you about 120-150 murders, or a My Lay each month for over a year….

The snipers would get 5 or 10 a day, and I think all 4 batalions had sniper teams. Thats 20 a day or at least 600 each month. Again, if I am 10% right then the snipers [alone] were a My Lay every other month.

In this letter, and two more sent the following year to other high-ranking generals, the sergeant reported that artillery, airstrikes and helicopter gunships had wreaked havoc on populated areas. All it would take, he said, were a few shots from a village or a nearby tree line and troops would “always call for artillery or gunships or airstrikes.” “Lots of times,” he wrote, “it would get called for even if we didn’t get shot at. And then when [we would] get in the village there would be women and kids crying and sometimes hurt or dead.” The attacks were excused, he said, because the areas were deemed free-fire zones.

The sergeant wrote that the unit’s policy was to shoot not only guerrilla fighters (whom US troops called Vietcong or VC) but anyone who ran. This was the “Number one killer” of unarmed civilians, he wrote, explaining that helicopters “would hover over a guy in the fields till he got scared and run and they’d zap him” and that the Ninth Division’s snipers gunned down farmers from long range to increase the body count. He reported that it was common to detain unarmed civilians and force them to walk in front of a unit’s point man in order to trip enemy booby traps. “None [of] us wanted to get blown away,” he wrote, “but it wasn’t right to use…civilians to set the mines off.” He also explained the pitifully low weapons ratio:

“Compare them [body count records] with the number of weapons we got. Not the cashays [caches], or the weapons we found after a big fight with the hard cores, but a dead VC with a weapon. The General just had to know about the wrong killings over the weapons. If we reported weapons we had to turn them in, so we would say that the weapons was destroyed by bullets or dropped in a canal or pad[d]y. In the dry season, before the monsoons, there was places where lots of the canals was dry and all the pad[dies] were. The General must have known this was made up.”

According to the Concerned Sergeant, these killings all took place for one reason: “the General in charge and all the commanders, riding us all the time to get a big body count.” He noted, “Nobody ever gave direct orders to ‘shoot civilians’ that I know of, but the results didn’t show any different than if…they had ordered it. The Vietnamese were dead, victims of the body count pressure and nobody cared enough to try to stop it.”

The Butcher of the Delta and Rice Paddy Daddy

During Ewell’s time commanding the Ninth Division, from February 1968 to April 1969, his units achieved remarkably high kill ratios. While the historical

“Hunt, who was our Brigade Commander for awhile and then was an assistant general…used to holler and curse over the radio and talk about the goddamn gooks, and tell the gunships to shoot the sonofabitches, this is a free fire zone,” wrote the Concerned Sergeant. Hunt, he said, “didn’t care about the Vietnamese or us, he just wanted the most of everything, including body count”; “Hunt was…always cussing and screaming over the radio from his C and See [Command and Control helicopter] to the GIs or the gunships to shoot some Vietnamese he saw running when he didn’t know if they had a weapon or was women or what.”

The sergeant wrote that his unit’s artillery forward observer (FO) “would tell my company commander he couldn’t shoot in the village because it was in the population overlay.” The battalion commander would then “get mad and cuss over the radio at my company commander and…declare a contact [with the enemy] so the FO would shoot anyway. I was there, and we wasn’t in contact but my company commander and the FO would do anything to get the

In a 2006 interview I conducted with Deborah Nelson, then a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, Ira Hunt claimed that the Ninth Division did not fire artillery near villages. He also denied any knowledge of the Concerned Sergeant’s allegations and argued against the notion that a command emphasis on body count led to the mass killing of civilians. “No one’s going to say that innocent civilians aren’t killed in wartime, but we try to keep it down to the absolute minimum,” he said. “The civilian deaths are anathema, but we did our best to protect civilians. I find it unbelievable that people would go out and shoot innocent civilians just to increase a body count.” But interviews with several participants in Speedy Express, together with public testimony and published accounts, strongly confirm the allegations in the sergeant’s letters.

The Concerned Sergeant’s battalion commander, referred to in the letters, was the late David Hackworth, who took command of the Ninth Division’s 4/39th Infantry in January 1969. In a 2002 memoir, Steel My Soldiers’ Hearts, he echoed the sergeant’s allegations about the overwhelming pressure to produce high body counts. “A lot of innocent Vietnamese civilians got slaughtered because of the Ewell-Hunt drive to have the highest count in the land,” he wrote. He also noted that when Hunt submitted a recommendation for a citation, citing a huge kill ratio, he left out the uncomfortable fact that “the 9th Division had the lowest weapons-captured-to-enemy-killed ratio in

During Speedy Express, Maj. William Taylor Jr. saw Hunt in action, too, and in a September interview he echoed the Concerned Sergeant’s assessment. Now a retired colonel and senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies,

Like Hackworth,

In August I spoke with Gary Nordstrom, a combat medic with the Ninth Division’s Company C, 2/39th Infantry, during Speedy Express, who described how the body count emphasis filtered down to the field. “For all enlisted people, that was the mentality,” he recalled. “Get the body count. Get the body count. Get the body count. It was prevalent everywhere. I think it was the mind-set of the officer corps from the top down.” In multiple instances, his unit fired on Vietnamese for no other reason than that they were running. “On at least one occasion,” he said, “I went and confirmed that they were dead.”

In recent months, I spoke with two Ninth Division officers who feuded with Ewell over division policies. Retired Lt. Gen. Robert Gard, who commanded the division’s five artillery battalions during his 1968-69 tour, spoke to me of Ewell’s heavy emphasis on body count and said he was never apprised of any restrictions about firing in or near villages. “There isn’t any question that our operations resulted in civilian casualties,” he told me in July. Gard recalled arguing with Ewell once about firing artillery on a village after receiving mortar fire from it. “I told him no, I thought it was unwise to do that,” he said in a 2006 interview with me and Deborah Nelson. “We had a confrontation on the issue.” Gard also served with Hunt, whom he succeeded as division chief of staff. When asked if Hunt, too, pressed for a large body count, Gard responded, “Big time.” “Jim Hunt dubbed himself ‘Rice Paddy Daddy,'” Gard recalled, referring to Hunt’s radio call sign. “He went berserk.”

Maj. Edwin Deagle served in the division from July 1968 until June 1969, first as an aide to Ewell and Hunt and then as executive officer (XO) of the division’s 2/60th Infantry during Speedy Express. In September he spoke to me about “the tremendous amount of pressure that Ewell put on all of the combat unit operations, including artillery, which tended to create circumstances under which the number of civilian casualties would rise.” Concerned specifically that pressure on artillery units had eroded most safeguards on firing near villages, he confronted his commander. “We’ll end up killing a lot of civilians,” he told Ewell.

Deagle further recalled an incident after he took over as XO when he was listening on the radio as one of his units stumbled into an ambush and lost its company commander, leaving a junior officer in charge. Confused and unable to outmaneuver the enemy forces, the lieutenant called in a helicopter strike with imprecise instructions. “They fired a tremendous amount of 2.75 [mm rockets] into the town,” Deagle recalled, “and that killed a total of about 145 family members or Vietnamese civilians.”

Deagle undertook extensive statistical analysis of the division and found that the 2/60th, one of ten infantry battalions, accounted for a disproportionate 40 percent of the weapons captured. Yet even in his atypical battalion, a body count mind-set prevailed, according to combat medic Wayne Smith, who arrived in the last days of Speedy Express and ultimately served with the 2/60th. “It was all about body count,” he recalled in June. When it came to free-fire zones, “Anyone there was fair game,” Smith said. “That’s how [it] went down. Sometimes they may have had weapons. Other times not. But if they were in an area, we damn sure would try to kill them.”

Another American to witness the carnage was John Paul Vann, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who became the chief of US pacification efforts in the Mekong Delta in February 1969. He flew along on some of the Ninth Division’s night-time helicopter operations. According to notes from an unpublished 1975 interview with New York Times Vietnam War correspondent Neil Sheehan, Vann’s deputy, Col. David Farnham, said Vann found that troops used early night-vision devices to target any and all people, homes or water buffalo they spotted. No attempt was made to determine whether the people were civilians or enemies, and a large number of noncombatants were killed or wounded as a result.

Louis Janowski, who served as an adviser in the Delta during Speedy Express, saw much of the same and was scathing in an internal 1970 end-of-tour report. In it, he called other Delta helicopter operations, known as the Phantom program, a form of “non selective terrorism.” “I have flown Phantom III missions and have medivaced [helicopter evacuated] enough elderly people and children to firmly believe that the percentage of Viet Cong killed by support assets is roughly equal to the percentage of Viet Cong in the population,” he wrote, indicating a pattern of completely indiscriminate killing. “That is, if 8% of the population [of] an area is VC about 8% of the people we kill are VC.”

An adviser in another Delta province, Jeffrey Record, also witnessed the carnage visited on civilians by the Phantom program during Speedy Express. In a 1971 Washington Monthly article, Record recalled watching as helicopter gunships strafed a herd of water buffalo and the six or seven children tending them. Seconds later, the tranquil paddy had been “transformed into a bloody ooze littered with bits of mangled flesh,” Record wrote. “The dead boys and the water buffalo were added to the official body count of the Viet Cong.”

The Cover-Up

In April 1969 Ewell was promoted to head II Field Force,

In the spring of 1970, as Ewell was readying to leave

It is common knowledge that an officer’s career can be made or destroyed in

…. Under such circumstances–and especially if such incentives as stand-downs, R&R [rest and relaxation] allocations, and decorations are tied to body count figures–the pressure to kill indiscriminately, or at least report every Vietnamese casualty as an enemy casualty, would seem to be practically irresistible. Vietnam

In June 1970 Webster sent a memo, with the review, to Resor, recommending that he confer with Westmoreland and Creighton Abrams, by then the top commander in

News of the atrocities in the Delta was already leaking into public view. That winter, veterans of Speedy Express spoke out about the killing of civilians at the National Veterans’ Inquiry in

Within days, Robert Komer, formerly a deputy to Westmoreland and chief of pacification efforts in

By this time, Ira Hunt had returned from

The lack of public exposure allowed the military to paper over the allegations. In August 1971, well over a year after the sergeant’s first letter to Westmoreland, an Army memo noted that the Criminal Investigation Division was finally attempting to identify and locate the letter writer–not to investigate his claims but “to prevent his complaints [from] reaching Mr. Dellums.” In September Westmoreland’s office directed CID to identify the Concerned Sergeant and to “assure him the Army is beginning investigation of his allegations”; within days, CID reported that the division had “tentatively identified” him and would seek an interview. But on the same day as that CID report, a Westmoreland aide wrote a memo stating that the general had sought the advice of Thaddeus Beal, an Army under secretary and civilian lawyer, who counseled that since the Concerned Sergeant’s letters were written anonymously, the Army could legitimately discount them. In the memo, the aide summarized Westmoreland’s thoughts by saying, “We have done as much as we can do on this case,” and “he again reiterated he was not so sure we should send anything out to the field on this matter of general war crimes allegations.” Shortly thereafter, at a late September meeting between CID officials and top Army personnel, the investigation that had barely been launched was officially killed.

Burying the Story

In 1971, something caught the eye of Alex Shimkin, a Newsweek stringer fluent in Vietnamese, as he pored over documents issued by the US Military Assistance Command,

They interviewed US civilian and military officials at all levels, combed through civilian hospital records and traveled into areas of the Delta hardest hit by Speedy Express to talk to Vietnamese survivors. What they learned–much of it documented in unpublished interviews and notes that I recently obtained from Buckley–echoed exactly what the Concerned Sergeant confided to Westmoreland and the other top generals. Their sources all assured them there was no shortage of arms among the enemy to account for the gross kills-to-weapons disparity. The only explanation for the ratio, they discovered, was that a great many of the dead were civilians. Huge numbers of air strikes had decimated the countryside. Withering artillery and mortar barrages were carried out around the clock. Many, if not most, kills were logged by helicopters and occurred at night.

“The horror was worse than

My Lai ,” one American official familiar with the Ninth Infantry Division’s operations in the Delta told Buckley. “But with the 9th, the civilian casualties came in dribbles and were pieced out over a long time. And most of them were inflicted from the air and at night. Also, they were sanctioned by the command’s insistence on high body counts.” Another quantified the matter, stating that as many as 5,000 of those killed during the operation were civilians.

Accounts from Vietnamese survivors in Kien Hoa and Dinh Tuong echoed the scenarios related by the Concerned Sergeant. Buckley and Shimkin spoke to a group of village elders who knew of thirty civilians who were killed when

Another older man from Kien Hoa, Mr. Ba, recalled, “When the Americans came in early 1969 there was artillery fire on the village every night and several B-52 strikes which plowed up the earth.” Not only did MACV records show bombings in the exact area of the village; the account was confirmed by interviews with a local Vietcong medic who later joined the US-allied South Vietnamese forces. He told them that “hundreds of artillery rounds landed in the village, causing many casualties.” He continued, “I worked for a [National Liberation] Front doctor and he often operated on forty or more people a day. His hospital took care of at least a thousand people from four villages in early 1969.”

Buckley and Shimkin found records showing that during Speedy Express, 76 percent of the 1,882 war-injured civilians treated in the Ben Tre provincial hospital in Kien Hoa–which served only one tiny area of the vast Delta–were wounded by US firepower. And even this large number was likely an undercount of casualties. “Many people who were wounded died on their way to hospitals,” said one US official. “Many others were treated at home, or in hospitals run by the VC, or in small dispensaries operated by the [South Vietnamese Army]. The people who got to Ben Tre were lucky.”

In November 1971 Buckley sent a letter to MACV that echoed the Concerned Sergeant’s claims of mass carnage during Speedy Express. Citing the lopsided kills-to-weapons ratio, Buckley wrote, “Research in the area by Newsweek indicates that a considerable proportion of those people killed were non-combatant civilians.” On December 2 MACV confirmed the ratio and many of Buckley’s details: “A high percentage of casualties were inflicted at night”; “A high percentage of the casualties were inflicted by the Air Cavalry and Army Aviation [helicopter] units”; but with caveats and the insistence that MACV was unable to substantiate the “claim that a considerable proportion of the casualties were non-combatant civilians.” Instead, MACV contended that many of the dead were unarmed guerrillas. In response to Buckley’s request to interview MACV commander Creighton Abrams, MACV stated that Abrams, who had been briefed on the Concerned Sergeant’s allegations the year before, had “no additional information.” Most of Buckley’s follow-up questions, sent in December, went unanswered.

But according to Neil Sheehan’s interview with Colonel Farnham, who served as deputy to Vann, by then the third-most-powerful American serving in

In the end, Buckley and Shimkin’s nearly 5,000-word investigation, including a compelling sidebar of eyewitness testimony from Vietnamese survivors, was nixed by Newsweek’s top editors, who expressed concern that such a piece would constitute a “gratuitous” attack on the Nixon administration [see “The Vietnam Exposé That Wasn’t,” below, which discusses Buckley and Shimkin’s investigation of atrocities, including one by a Navy SEAL team led by future Senator Bob Kerrey]. Buckley argued in a cable that the piece was more than an atrocity exposé. “It is to say,” Buckley wrote in late January 1972, “that day in and day out that [the Ninth] Division killed non combatants with firepower that was anything but indiscriminate. The application of firepower was based on the judgment that anybody who ran was an enemy and indeed, that anyone who lived in the area could be killed.” A truncated, 1,800-word piece finally ran in June 1972, but many key facts, eyewitness interviews, even mention of Julian Ewell’s name, were left on the cutting-room floor. In its eviscerated form, the article resulted in only a ripple of interest.

Days before the story appeared, Vann died in a helicopter crash in

Ewell retired from the Army in 1973 as a lieutenant general but was invited by the Army chief of staff to work with Ira Hunt in detailing their methods to aid in developing “future operational concepts.” Until now, Ewell and Hunt had the final word on Operation Speedy Express, in their 1974 Army Vietnam Studies book Sharpening the Combat Edge. While the name of the operation is absent from the text, they lauded both the results and the brutal techniques decried by the Concerned Sergeant, including nighttime helicopter operations and the aggressive use of snipers. In the book’s final pages, they made oblique reference to the allegations that erupted in 1970 only to be quashed by Westmoreland. “The 9th Infantry Division and II Field

Ewell now lives in

George Lewis, the man tentatively identified by the Army as the Concerned Sergeant, hailed from

To this day, Vietnamese civilians in the Mekong Delta recall the horrors of Operation Speedy Express and the countless civilians killed to drive up body count. Army records indicate that no Ninth Infantry Division troops, let alone commanders, were ever court-martialed for killing civilians during the operation.

Addendum:

The

Although he was the son of a military man, Alex Shimkin went to

Buckley, now a contributing editor at Playboy and adjunct professor at

“Pacification’s Deadly Price,” a joint investigation into the slaughter of Vietnamese civilians by US troops during Operation Speedy Express [see “A My Lai a Month,” The Nation, December 1, 2008], was the crowning achievement of the two men’s working partnership. But the potentially explosive story was held for months and finally published only in gutted form on June 19, 1972. Further undermining their investigation’s impact, Newsweek allowed a former top US official in Vietnam, who had secretly learned of the existence of “hundreds” of examples of the very kinds of killings Buckley and Shimkin sought to expose, to critique the story in its own pages, without allowing for a full rebuttal. Recently, Buckley shared with me the unexpurgated version of the story and subsequent drafts, along with his and Shimkin’s original notes.

Although a

Buckley and Shimkin’s investigation revealed that the grossly disproportionate kills-to-weapons-recovered ratio of 14.5 to 1 achieved by the Ninth Infantry Division during Speedy Express was not due to a lack of weapons among the guerrillas, but the fact that thousands of civilians were killed. They learned that most of these deaths were the day-to-day result of civilians, individually or in small clusters, being fired upon at night and from the air. They uncovered multiple mass killings as well. Shimkin’s notes show that he found evidence of one massacre by US forces in February 1969 that left forty to fifty Vietnamese, mostly women and children, injured or dead. Interviewing an injured survivor as well as a woman who had lost her mother in the bloodbath, Shimkin learned that US troops had ambushed a flotilla of civilian sampans near the border of the Delta provinces of Kien Phong and Dinh Tuong.

In their analysis of disproportionate kill ratios, Buckley and Shimkin came across other atrocities, one of which would finally make waves some thirty years later. Shimkin’s review of official MACV documents found that on February 11, 1969, Ninth Infantry Division troops engaged three motorized sampans, reportedly killing twenty-one enemies, without any

That last mission came to prominence when it was revealed that future Senator Bob Kerrey led the SEALs on that February 26 operation into the

In 1998 Newsweek killed a story about that massacre, by reporter Gregory Vistica. As Vistica wrote in his 2003 book, The Education of Lieutenant Kerrey, when Kerrey bowed out of the upcoming presidential race, a top editor at the magazine told him that publishing “a piece on Kerrey’s actions in Vietnam…would unfairly be piling on.” The massacre would remain Kerrey’s secret until Vistica, having left Newsweek, published an exposé in The New York Times Magazine in 2001.

Twenty-six years before its editors killed Vistica’s article, Newsweek held, and then eviscerated, Buckley and Shimkin’s story on much the same logic. In January 1972, Buckley cabled the first draft of his and Shimkin’s article from Saigon to

The inside word, at MACV and the Pentagon, was that the military was deeply concerned about Buckley and Shimkin’s findings. But instead of rushing the story into print, Newsweek pushed back on the piece, with New York editors objecting to Buckley’s linking of My Lai and Speedy Express; claiming that articles about civilians killed by “indiscriminate” fire were nothing new; and requesting that the draft be radically shortened. Buckley–in heretofore private cables–responded by pointing out that the military was afraid specifically because the article dealt with command policies. “[D]ay in and day out,” Buckley wrote, the Ninth Division “killed non combatants with firepower that was anything but discriminate.”

Shimkin headed back into the Delta for further reporting, where he turned up more Vietnamese witnesses, and Buckley rewrote the article striving to get the piece into print before his scheduled departure from

Buckley handed over the reins of the bureau and took a long vacation with the article still in limbo. When he returned to

The story of Speedy Express should have been more explosive than Seymour Hersh’s expose of

“The facts which are readily available suggest answers to many of Newsweek’s questions. And the answers suggest that ‘Speedy Express’ was a success at a criminal price. [MACV] said that if Newsweek could provide information to indicate civilians were killed in large numbers ‘the command would like the opportunity to follow up on it.’ It has that opportunity now.”

“Pacification’s Deadly Price,” was devastated by editing that excised much of Buckley and Shimkin’s reporting, including an entire sidebar of Vietnamese witnesses. In the end, military officials were never pressed on the findings of the investigation and were able to ride out the minor flurry of interest it generated. Had the Army been called to account; had a major official investigation, akin to the Peers Commission that unraveled the details of the

That never happened.

John Paul Vann, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who became a high-ranking civilian official in Vietnam, ducked Buckley and Shimkin as they investigated Speedy Express, and he died in a helicopter crash days before their story was published. His Newsweek obituary, with a laudatory quote from Robert Komer, the former

About a month after Vann was buried, Alex Shimkin accidentally crossed North Vietnamese Army lines in

A week later, Newsweek published a letter by Robert Komer that critiqued “Pacification’s Deadly Price” on the grounds that Speedy Express was, in his eyes, “not part of the ‘pacification’ program,” as Buckley contended, while largely disregarding, in Komer’s words, “whatever the U.S. Ninth Division allegedly did.” Although it was well known that military and pacification efforts were inseparably linked, Komer accused the magazine of tying Speedy Express to such efforts “to get a striking headline,” and he even invoked Vann’s name to paint the piece as a “slur” on “American pacification workers.”

Buckley later told Knightley, “I pressed Newsweek to run a second piece. I wanted to expose the Pentagon’s defense and demolish [Komer’s letter]. But Newsweek refused to carry a second article and I was allowed only a tiny rebuttal to Komer.” Neither Buckley nor Newsweek knew that more than a year earlier, in April 1971, Komer had written a personal note to Vann about allegations of civilian slaughter by US helicopters in the Delta in which he confided that the reports sounded “all too true.” And in May 1971, Vann, who that month became the third most powerful American serving in

Research support for this article was provided by the Investigative Fund of The Nation Institute. Research assistance was provided by George Schulz of the Center for Investigative Reporting, Sousan Hammad and Sophie Ragsdale.

Nick Turse is the associate editor and research director of Tomdispatch.com. He is the author of The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives and a forthcoming history of

This two-part article appeared in the December 1, 2008 edition of The Nation and on line on November 13, 2008.It was posted at Japan Focus on November 21, 2008

Recommended Citation: Nick Turse, “A My Lai a Month: How the