Vietnamese Agent Orange Victims Sue Dow and Monsanto in US Court

By Ngoc Nguyen and Aaron Glantz

[The American war in Southeast Asia featured the most widespread use of chemical warfare since World War I. Earlier, the British had resorted to chemicals in their colonies, Italy did so in Ethiopia, and Japan in China in the 1930s and 1940s. These were lethal chemicals where the Americans thought theirs were not. Iraq in the 1980s made the largest-scale known use of lethal chemical weapons in its Iran war and against its Kurdish minority. But two elements distinguished the U.S. effort in Vietnam. First, massive quantities of these chemicals were used, as the below article makes clear. The amounts cited are equivalent to roughly 60,000 tons of chemical agent. By comparison, in the 1972 Christmas Bombing of North Vietnam, which some hold to be the decisive air campaign of the war, and including both B-52 bombers and tactical aircraft, the Nixon administration loosed some 36,000 tons of munitions over Hanoi and its environs.

The Christmas Bombing of Hanoi

Second, the Americans resorted to chemicals with poorly understood effects. The main defoliants utilized by the U.S. in the Vietnam War, Agents Purple, Blue—and, best known—Agent Orange, contained ingredients found to be carcinogenic in studies by the U.S. National Cancer Institute in 1969 and subsequently banned from use in the United States.

There were two main propagating methods for the defoliant chemicals used in the Vietnam War. Operation Ranch Hand, which has garnered the most attention, was an aerial spraying initiative begun on an experimental basis in January 1962 and continued until January 7, 1971, though in its last years on a greatly reduced basis. In 1967, its peak year, Ranch Hand defoliated 1.2 million acres of land and dispensed 4.8 million gallons of chemicals. The other technique used vehicles and manual dispensers to defoliate land surrounding military bases, villages, and roads.

Aerial defoliation with Agent Orange

Manufacturers of these chemicals in the U.S. acknowledge no responsibility, but reached an out-of-court settlement with American veterans’ groups as long ago as 1984, and the Veterans Administration in the United States awards disability status for validated claims of Agent Orange exposure. No doubt it is due to the huge liabilities that might flow from a successful claim that the chemical companies have so long resisted Vietnamese efforts to obtain similar redress. In the article here, Ngoc Nguyen and Aaron Glantz show some of the personal and societal consequences of the chemical war in Vietnam. ~John Prados]

ROK troops rally on behalf of claims

for compensation for Agent Orange exposure

HANOI – Vietnam, which is bidding for World Trade Organization membership and is already signatory to a trade deal with its former nemesis in Washington, is still grappling with the huge social and economic consequences of its military conflict with the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

The legacy of the United States’ use of Agent Orange tops that list. From 1962 to 1971, the US military dumped an estimated 83 million liters of highly toxic herbicides, including Agent Orange, mostly over Vietnam but also Laos and Cambodia, in an attempt to flush out jungle-covered guerrilla fighters. Agent Orange contained trace amounts of dioxin, a toxic substance known to cause cancer in humans at high doses.

A group of alleged Vietnamese victims are the first to seek legal redress and compensation from the US companies, namely Dow Chemical and Monsanto Corp, that then manufactured the chemical. In their complaint filed in New York, they claimed the defoliant had caused widespread birth defects, miscarriages, diabetes and cancer, and should be considered a war crime against millions of Vietnamese.

The chemical companies, for their part, have maintained that no such scientific link has ever been proved, and that the US government, not the companies, should be held responsible for how the chemical was deployed.

A US judge this month threw out the case against the companies, ruling that there was no legal basis for the alleged victims’ claims. The court had come under heavy lobbying from the US Justice Department to rule against the plaintiffs, because of Washington’s fears of the legal precedent it would set in other countries ravaged by US military interventions.

The Vietnamese veterans’ association has appealed the ruling, and hearings in that appeal are to commence next month.

The case is widely viewed as an important expression for Vietnam’s still small but increasingly assertive grassroots movements. In Hanoi, an international conference this month examined the social impacts of the wartime herbicide – a meeting that probably wouldn’t have been possible without government support just a few years ago. Until now, research on the effects of the chemical has focused primarily on science that proves a link between dioxin exposure and numerous diseases.

The veterans’ group points to thousands of documented cases of birth defects. Consider the case of Nguyen Thi Thuy, who left her village when she was 22 to help build roads for the North Vietnamese Army during the war. She remembers crawling into tunnels during the day and covering her mouth with a wet rag when the US military sprayed the landscape with defoliant.

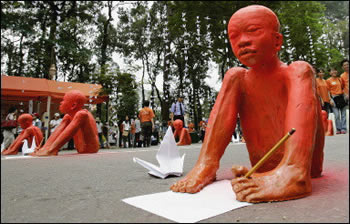

Sculpture by Vietnamese students of

disabled child victims of Agent Orange

”I didn’t know what it was then, but it was white,” she recalled. ”The sky and earth were scorched. The earth had lost all its greenery. We didn’t know it was Agent Orange at that time.”

Thuy returned home in 1975 and started a family. ”When my daughter was born, everyone could see through her stomach,” said Thuy. ”It was like looking through translucent paper. You could see her intestines and liver. She died several hours later.”

Thuy had two more children – one was normal and the other developmentally disabled – but she would keep her guilt, shame and pain to herself until 2002. At a gathering of female veterans of the Vietnam War, she met others who had suffered miscarriages and had given birth to malformed babies.

Thuy is one of the lucky ones. Most Vietnamese people exposed to Agent Orange receive little or no specialized health care from the government. Thuy is one of only a hundred victims receiving treatment at Friendship Village, a clinic 20 kilometers outside Hanoi funded by American and other foreign veterans of the war.

The Vietnamese government, which for decades publicly documented the impact of Agent Orange on civilian populations at its War Crimes Museum in Hanoi, recently toned down the exhibition in line with a warming trend in relations with Washington.

War Crimes Museum, Hanoi

However, where the Vietnamese government has gone quiet, grassroots movements are taking up the cause with renewed vigor. In 2004, the Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange sued 36 US companies that manufactured and supplied the defoliant during the war.

Thuy’s story resembles many of the personal stories documented by researchers at the Center for Gender, Family and Environment in Development. The grassroots group is working to bring more and more people’s stories out of the war’s shadow. ”Nowadays, people talk more about Agent Orange, because we have the lawsuit,” said Pham Kim Ngoc, deputy director of the non-governmental group, which organized last month’s two-day conference.

Environmental scientist Vo Quy, a consultant on the lawsuit who traveled to central and south Vietnam in 1970 and 1974 to study the impacts of Agent Orange, said he found victims suffering silently. ”In Vietnam, people with deformed children [fear] that neighbors [would] believe the family did something immoral in order to have deformed children – to have compassion for children, they didn’t tell anyone,” said Quy.

Quy continued: ”If they say their children were exposed to Agent Orange, then the stigma will transfer to children and they would not be able to get married, so they hid it. The government did not want to publicize it, because the victims had suffered enough. If people knew about Agent Orange-related illnesses, later the victims would suffer more stigma and shame.”

Tran Thi Hoa served from 1973 to 1976 and spent one year in Laos. After her service, she returned home, but never married. The 51-year-old seamstress said she always thought about work and never thought about finding a husband. Now, she’s afraid she’ll have no one to care for her when her parents die.

”After I was discharged, I was healthy,” recalled Hoa tearfully. ”It wasn’t until 27 years later that I started to get sick and my hands and feet started to curl outward and shrivel up. Before, my hands and feet were not like this. I was able to work, but now I can’t. I can’t even take care of myself.”

As more Vietnamese become aware of the consequences of Agent Orange, they are voicing their experiences and expressing their expectations and needs through global channels.

Hoa said she’d like to receive compensation so she can hire an attendant to take care of her for the rest of her life. Thuy, meanwhile, wants to know who will take care of her disabled children when she’s gone. And there are tens of thousands of other questions Vietnamese are just now finding the voice to ask their former US adversaries.

This article appeared in Asia Times on March 20, 2006 and at Japan Focus on May 16, 2006.

Aaron Glantz is a reporter for Pacific Radio and author of How America Lost Iraq.

John Prados is a senior analyst with the National Security Archive. His recent books are Hoodwinked: The Documents that Show How Bush Sold Us a War and Inside the Pentagon Papers.