The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War

Kim Dong choon

The Other War: Korean War Massacres

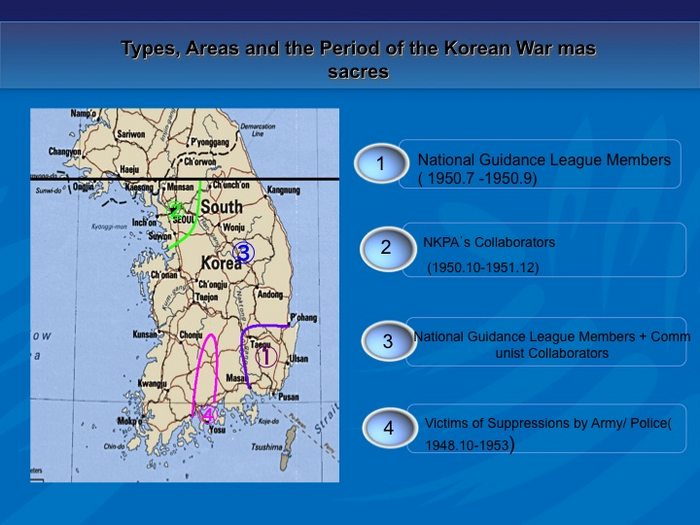

More than 2 million people were killed during the Korean War. The casualties included not only military personnel but also innocent civilians. Few are aware that the Korean authorities as well as US and allied forces massacred hundreds of thousands of South Korean civilians at the dawn of the Korean War on June 25, 1950. The official records of government, military and police, as well as survivor testimonies, reveal that mass killings committed by South Korean and U.N forces occurred before and during the Korean War (June 1950 to July 1953). These incidents may be categorized into four types.

The first category involves summary executions of civilians and political prisoners suspected of opposing or posing a threat to the ROK (Republic of Korea) regime. Under orders to carry out “preventive detention,” the authorities arrested the victims shortly after North Korea’s attack.[1] Most of the detainees were political prisoners including members of the Bodoyeonmang (National Guidance League or NGL), a government‐established organization whose purpose was to control and monitor former and converted communists.

Although NGL membership was declared voluntary, the authorities registered former communists or anti‐government activists to monitor their activities and location. Over time, membership expanded to include villagers who participated in anti‐government organizations. The Police Bureau, moreover, ordered regional police chiefs to fill specific quotas for NGL membership. These chiefs, lacking information in many cases, arbitrarily targeted individuals for membership. Thus, some NGL members were villagers with no political ideology or ties to anti‐government organizations.

In 1950, at the outbreak of the war, there were approximately 30,000 political prisoners imprisoned in South Korea. Many were detained for violating the National Security Law. Most of these prisoners would later “disappear” after the outbreak of war. The evidence the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) has uncovered suggests that a majority of them were secretly executed along with NGL members between July and August of 1950. The killing of NGL members surpassed other atrocities of the Korean War in its sheer size and brutality.

The second category involves the arrest and execution of suspected North Korean collaborators by the ROK police and rightist youth groups. Both North and South Korean forces conducted executions to prevent people from supporting their opponents. As South Korean forces advanced to recapture lost territory, they and local rightists began eliminating suspected “collaborators” without judicial proceedings. This occurred shortly after retreating North Korean soldiers conducted large scale massacres as they fled the advancing US and ROK forces.[2]

The third category includes killings conducted during ROK counterinsurgency operations against communist guerillas. The victims primarily resided near areas with active guerillas in the Southern Mountains. Witnesses residing in the targeted areas described the tactics used as brutal. The ROK employed a three-all policy (kill‐all, burn‐all, loot‐all), which was a scorched earth policy used by Japanese Imperial forces while suppressing anti‐Japanese forces in China.

The remains of 110 victims of the mass executions of political prisoners in 1950 in Cheongwon, Chungbuk, south of Seoul. August 2007 photo, TRC

Counterinsurgency atrocities also occurred in North Korean occupied territory. As the ROK police and rightist youth groups followed the U.S. military across the 38th parallel, they encountered people they suspected to be communists and collaborators. A typical massacre occurred in Sinchon (a county located in southern North Korea). North Korea accused American troops of killing 35,380 civilians, but newly released documents disclose that right‐wing civilian security police, assisted by a youth group, perpetrated the massacre. [3]

The fourth category involves civilian and refugee deaths from bombings and shootings in U.S. combat operations. Under the mandate of “maintaining and restoring international peace,” the U.S. deployed soldiers to the Korean Peninsula after North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. The Eighth U.S. Army, which was stationed in Japan, landed in Korea in July 1950, but proved ill‐prepared to repel the communist forces. Due to confusion and panic, American forces killed a number of civilians in the largest single massacre, the No Gun Ri Incident.

While some of the victims were left leaning or sympathetic to North Korea, the majority consisted of innocent civilians. The U.S. and South Korean authorities suppressed this incident, arguing that disclosure of information would threaten the ROK’s constitutional order and national security. As a result, it remains unknown even to many who lived through the war. Considering the severity and number of massacres, these incidents may be called “the other war.” In order to prevent similar tragedies from reoccurring in the future and ensure peace on the Korean Peninsula, the truth must be investigated and publicized.

A History of Silencing Bereaved Families and Oppressing Memories of Atrocities

After the 1960 student uprising toppled the U.S.‐supported Rhee Syngman government, bereaved families initiated a series of demonstrations to demand investigation into mass killings during the war. They established an organization, the National Association of Bereaved Families of Korean War Victims, which exhumed and properly buried the victims’ remains in a joint cemetery they built to honor the dead.

In response to the large number of petitions from bereaved families, the National Assembly quickly organized the Special Committee on the Fact‐finding of Massacres. However, after the May 16 Coup in 1961, the new military government disrupted these efforts by arresting and prosecuting the leaders of the association and demolishing the joint cemetery. These actions sent a clear message that any person attempting to raise the issue of truth verification on deaths during the Korean War would be regarded as a communist and considered a threat to the state.

For 27 years (1961‐1987), under the military dictatorship, all sympathetic discourse on raising awareness of massacres was subject to prosecution. The bereaved families suffered severe discrimination as authorities systematically marginalized them from civil society and politics and placed them under police and Korea Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) surveillance.

Frantic anti-communism paralleled the rise of McCarthyism in the U.S., heavily influencing South Korea’s political atmosphere from 1953 onward and resulting in society’s collective amnesia over the mass killings committed by ROK and U.S. troops. Politicians and major media outlets under the authoritarian regime were reluctant to cover or even mention the incidents. This attitude continued down to today as authorities and the media repeatedly ignore investigations and the pleas of heartbroken victims. Instead, journalists copy foreign‐based news sources whenever relevant material surfaces such as the Associated Press story on the No Gun Ri Incident. The Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade never officially commented on the U.S. “No Gun Ri Report” which held that the mass killings had occurred in the midst of combat operations and the dead were therefore deemed collateral damage.[4]

This whitewash led to the widely‐held view that the South Korean authorities killed the victims three times; first, their lives were taken in the massacres (1948‐1953); second, they were killed again when authorities disregarded their bereaved families’ requests for investigation; and finally, they were killed a third time when their family members were branded as “communists” due to guilt by association and the charges of massacre suppressed.

The systematic repression of these bereaved families lasted until the late 1980s. Just as the denial of the Holocaust is painful to Holocaust victims and their families, Korea’s bereaved families suffered similar pain as the state disavowed the incidents and previous authoritarian regimes discredited and repressed those considered “guilty by association”. This tactic was effectively used to exclude alleged political opponents.

The forced amnesia under successive military dictatorships silenced the survivors and the victims’ families, preventing them from revealing their long untold stories. After half a century, these survivors have yet to completely recover from their trauma. The inhumane treatment the survivors experienced continues to haunt them, and the memories of the events remain deeply etched into their hearts.

Public negligence and silence in both the United States and Korea are not just the result of the passage of time; they are also due to the collective amnesia imposed on society by the state. While scholars and journalists have raised awareness of such issues as Korean War massacres, it was essential that an official institution be given appropriate authority to investigate and verify these cases, and inform the public. This was the mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Only after the Commission completes the truth verification process can people begin to restore the honor of the victims and conduct memorial services for the dead.

From Isolated Cases of Dealing with the Past to Comprehensive Redress

After the demise of the military regime (1987), bereaved families of Korean War massacres were able to give voice to long-repressed grievances. The victims’ families of the Guchang and Jeju April 3 massacres initiated the practice of revealing their suffering on the platform of political democratization.

The Guchang incident of February 6-9, 1951, was one of many massacres that occurred early in the Korean War.[5] Shortly after the massacre, the events surrounding it were disclosed by Jung‐mok Shin, a National Assembly member representing Guchang, who risked his life to reveal the facts. The Rhee government responded to public outrage at the massacre of civilians by ‘gesturing’ toward punishing the commanders responsible. However, they were released immediately and received amnesty within just two years, while the victims were not rehabilitated and the truth of the incident remained concealed. After President Rhee resigned following the April 19, 1960 Student Uprising, the surviving families assembled to reveal the facts and identify the local police and officials who had collaborated with the military.

Under such democratic conditions, many more survivors and family members of Korean War victims began to demand settlement of their grievances. They called on the government to prosecute the perpetrators and investigate the massacres. The National Assembly quickly organized a special committee to probe the incident and later issued a report. They also called on the Assembly to enact a law to comprehensively investigate the incidents and reconcile the victims’ families and survivors. However, these efforts abruptly ended on May 16, 1961, when the military staged a coup. The National Assembly’s investigation immediately ended and leading social movement figures were arrested as pro-communist agitators. Their call for full clarification of the massacres and relief to the survivors’ suffering was silenced.

The Jeju April 3 incident of 1948 occurred shortly before the first general election, and was unique in the number of victims, and the lasting effect on the Jeju Island. [6] Embedded in a strong collective regional identity, the Jeju people’s tragedy became a popular theme for novels and poems. While the victims’ families fought alone to settle the Guchang incident, the Jeju Incident succeeded in drawing the active support of intellectuals and activists and received wide local media attention. Its historical importance in the road to the establishment of the divided governments in the Korean peninsula and the strong sense of collective victimization of Jeju people contributed to making it a national agenda after democratization. The transformation of the political and ideological landscape conditioned by democratization, along with supporters petitioning for reconciliation, emboldened the surviving families to divulge their stories. Scholars and journalists have confirmed that most of the victims of the Incident were innocent civilians, whose stories are now told in the April 3 Peace Park and Memorial Museum which opened in 2008.

Prayers at the wall inscribing the names of the estimated 30,000 Jeju victims in the Jeju Peace Memorial Park

Over the opposition of right‐wing forces, civilian governments under Kim Young‐Sam and Kim Dae‐jung, eventually passed several laws to settle these two unresolved historical cases. The Guchang Special Law was passed in 1996 with the objective of restoring the honor of the victims. This was followed by the Jeju Special law, Special Act for Investigating the Jeju April 3 Incident and Recovering the Honor of Victims (2000). The final law, Restoring the Honor of the Victims, was enacted to investigate the facts and restore the honor of victims who had long been branded communists.

The two special committees tasked with investigating and restoring the honor of the victims, faced difficult assignments. In accord with the Guchang Special Law, the tasks of restoring the honor of victims and establishing a memorial are nearly complete, and the victims’ families are currently demanding reparations. The Jeju committee also completed its investigation and began preparing for reconciliation. However, doubts remain as to whether the Jeju committee can fully reveal the truth of the Jeju Massacres and and identities of the victims. The most sensitive investigation has involved the role of the U.S. military during counterinsurgency operations against rebel forces. While the final report failed to confirm or spell out a U.S. role, it concluded that 86% of the 14,373 deaths reported were committed by security forces including the National Guard, National Police, and rightist groups.[7]

President Roh Mu‐hyun visited Jeju on April 3, 2006 and officially apologized for the abuses perpetrated by the previous government and expressed his condolences to the Jeju April 3 victims. The report officially changed the existing name of the incident from the April 3 Jeju Rebellion Incident, to the “Jeju April 3 Incident”. The official name change from ‘Rebellion Incident’ to ‘Incident’ signified a re-understanding of history. Under successive dictatorships, the South Korean government had highlighted the aspect of guerilla rebellion against the U.S designed state-building in a divided Korea while neglecting the civilian casualties through the suppression policy. While controversy continues over the name and nature of the events, the Korean government’s official recognition of the Jeju April 3 Incident civilian victims is a crucial step on the road of historical settlement of Korean War massacres. The recognition makes it possible for most victims and their bereaved families who were long stigmatized as ‘communist rioters’ to restore their honor.

The Associated Press’s reports on the No Gun Ri Massacre of some 300 civilians by U.S. forces in July 1950, and the release of reports concerning similar incidents, attracted public concern about mass killings by U.S. forces. After the publication of the U.S. Army’s report, President Bill Clinton ordered an official investigation and issued a statement of ‘regret’ for the killing of Korean refugees, but this failed to satisfy many Koreans who expected a formal apology.[8] The U.S. made a gesture toward the victims by offering one million dollars to erect a monument and created a $750,000 scholarship fund. However, the U.S. provided no restitution to the victims and made no judgment on charges that the massacre was committed under direct orders by U.S. officers. The No Gun Ri victims’ families rejected the U.S. gesture, above all because it included no official apology, but also because the small scholarship fund was meant to cover all U.S.-inflicted civilian casualties that occurred during the Korean War. A No Gun Ri Peace Park is now under construction by the Korean government.

The activities on behalf of the victims of Jeju and No Gun Ri attracted national attention and encouraged leaders of other bereaved family associations to petition the National Assembly to settle their grievances. However, recognizing the injustice of settling isolated incidents while ignoring hundreds of other cases, they called for the enactment of the Special Act on Unveiling the Truth of the Massacres of Civilians in order to “correct the distorted history.”

After over half a century, social movements have emerged in response to the outcry of the bereaved families to campaign for the restoration of honor to the victims and survivors by rectifying the distorted history that buried the truth. Civil rights activists, sympathetic lawmakers, and the Roh Mu‐hyun government concluded that a special law with comprehensive measures should be enacted to address the many outstanding issues of massacres. After both the public and government approved of this, the Framework Act for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was drafted and passed.

The Petitions 55 Years Later

The death of the head of a family brought total ruin to a house. In order to survive, many widows remarried, resulting in a situation in which some children became virtually orphans who were cared for by grandparents or relatives. A lack of education, property, and social welfare reduced them to the lowest status of Korean society.

Victims and bereaved families deserve to be informed of the truth of illegal killings and receive official recognition by government and society. The families also deserve sympathy and compensation for their losses. The primary stimulus for the government to initiate past settlement has been the bereaved families’ petitions. The victims’ families’ persistent demand for truth‐confirmation and official recognition of victimization finally culminated in 2005 in the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and has influenced its work.

As the voices of the bereaved families opens the way for Korean society to confront its tragic past, the primary objective for the families is to restore their family members’ dignity. The scope of their concern is usually restricted to familial problems. The families’ long period of suffering and estrangement from society prevented them from trusting nonfamily relationships. While desiring official recognition of their parents’ illegal execution and government abuse, many struggled with a dilemma. Should they demand settlement from the same state that condoned or even ordered the killings? Although the government perpetrated the massacre and discriminated against families, the bereaved families’ only option was to appeal to the same state for grievance settlement. The change of regime from dictatorship to democracy emboldened many to appeal.

Since the Commission’s inception, bereaved families have submitted petitions for truth verification. More than five decades since many of the victims’ executions occurred, the government prepared to receive petitions from bereaved families. In some cases all of the family members were killed in the incident, or the remaining members had either passed away or relocated. Without survivors or witnesses, the exact details of the victimization remained unknown. The fifty-year lapse of time and the social dislocation of the era limited the number of petitioners. For many families, it was too late to apply for truth verification, which is why they did not petition after the Commission called for applications.

Some families, who were well aware of the Commission’s work, were reluctant to apply, remembering the oppression and abuse they suffered under the military government in 1961 and their subsequent estrangement from society. These traumatic experiences prevented many from submitting petitions.

People who had reached high socioeconomic status also refrained from applying based on the fear that truth‐confirmation could undermine their status. For Koreans, the welfare of the child is most significant and they forgo the restoration of dignity through truth verification due to the threat it poses to the descendants’ happiness. Thus, the act of petitioning for the most part has involved the disadvantaged among victimized families.

The experience of segregation, ignorance, and suffering led to avoidance or resignation by the victims’ families. This demonstrates the extent of their trauma. It is estimated that the 7,800 applications received by the Commission represent only ten percent of the total number of victims.

Investigation and Confirmation by the Commission

The basic questions raised by the victims’ family members concern the identity of the killer, the circumstances, time, and motive for the killing. The Commission must answer questions beyond individual cases and also investigate a second type of truth – the historical and societal truth that includes the background, cause, situation, perpetrators, mechanism of killing, death toll, identification of victims, and legal responsibilities of the governments involved. While the Commission can confirm the legal, political, or moral responsibility of the government and chain of command, the law includes no provisions for punishing the perpetrators. The law does stipulate that “for a perpetrator actively cooperating with the Commission by confessing his/her crime during the investigation, and his/her confession is consistent with the facts of the investigation, the TRC may recommend to the relevant institution that immunity be granted or punishment be minimized during criminal investigation or trial procedure.” But this article is meaningless since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has no authority to punish perpetrators.

The Commission is assigned the task of responding to the bereaved families and Korean society’s questions concerning past incidents. By verifying the truth of historical events, the Commission seeks to foster reconciliation between victims and perpetrators. It is also entitled to offer recommendations to reinstate the honor of the victims, to promote reconciliation between confessed perpetrators and victims, revise policies in order to prevent similar atrocities from reoccurrence, and establish truth‐finding research institutes. Although these duties are critical, the chief task of the Commission is truth confirmation and these results are published in a bi‐annual report.

The verification of most petitions filed at the Commission has been difficult and protracted. This is partially due to the time passed since the incidents occurred. Despite the Commission’s careful approach to evidence, there remained constant doubts as to whether the truth could be verified without strong authority to investigate alleged perpetrators. Since most concerned figures and witnesses have already passed away, and many related documents have been systematically destroyed or disappeared, it is almost impossible to reconstruct many events from fifty to sixty years ago. This has not prevented the Commission from acquiring some crucial testimonies and documents from the government, and this has contributed to the reconstruction of the country’s uncovered history.[9]

Thorough listening to the bereaved families’ statements proved to be a crucial initial step towards healing. The investigators’ visits to victim families were often the government’s first acknowledgement of the petitions. Some petitioners confided that they hadn’t told their families’ tragic stories to anyone including their children in more than 50 years. When final confirmation of the truth regarding the petitioner’s parents is issued by the Commission, and it is confirmed that innocent parents were killed by the state, the Commission found that there was a great sense of relief from the burden of repressed trauma. This was clear in the mood and voices of the bereaved families during official memorial service following the Commission’s decision.

According to the Commission, the truth is expected to be decided through deliberation and discussion among the commissioners. The commissioners are expected to represent the different social sectors of Korean society including judicial, religious, and academic circles. The investigators conduct research on the cases or incidents and submit a final report after investigating the petitioners’ statements, witnesses’ testimonies, and related documents. While most human rights abuses cases are investigated on the basis of individual petitions, massacre cases are generally divided into several big incidents such as the National Guidance League Incident, U.S bombing- related incidents, or the collaboration incidents. Afterwards, the sub‐commission examines the results before transferring the case to the Commission.

The resolution of the Commission is reached after long discussions and disputes during meetings. The Commission’s final decision is then issued and is entitled to be regarded as the official verdict. Although verification follows a rigorous process to ensure fairness, each party concerned may still reject it. While most petitioners accept the verdict, some dismiss it as incomplete, for example for the failure to name responsible official perpetrators, whether Korean or American. Perpetrators who are military officials and police officers, for their part, often blame the Commission for tarnishing their honor since they have long officially enjoyed the position of national heroes in fighting against the North Korean communists. In one case, a group of extreme rightists filed a lawsuit against the president of the Commission accusing him of betraying the truth and defaming their honor. However, the truth confirmed by the Commission should be valued because of its careful investigation and deliberation.

Remaining Tasks

The Commission may not be the only path for settlement of historical grievances, but its truth‐confirmation activities constitute a cornerstone. The Commission must complete its remaining tasks, and achieve closure by revealing suppressed stories, thereby leading toward reconciliation. Upon successfully completing its mission, the Commission will assist in building a more unified nation and provide a model for other nations that choose to pursue truth‐seeking activities.

Subsequent measures are to be implemented by the Recommendations Follow‐up Board under the Ministry of Public Administration and Security. However, little progress has been made toward establishment of a truth‐finding research institute. A specific example of the importance of creating such an institute is the 54 cases of civilian deaths from U.S. Air Force bombings (ten incidents). Recommendations from the TRC include an official state-sponsored memorial event, as well as efforts seeking compensation for the victims through negotiations with the U.S. government. Some measures like sponsoring memorial services have been taken. Both the South Korean and U.S. governments [10], however, have failed to respond to other recommendations of the Commission.

On January 24 of 2008, President Roh Mu‐hyun publicly apologized for the government’s illegal exercise of public power in the case of the Ulsan National Guidance League victims and families. President Roh expressed the government’s position regarding the settlement of historical issues and officially recognized the illegal exercise of power by past governments. This official recognition and presidential apology to the Ulsan victims, however, was only a symbolic expression before finishing his term and did not stipulate any following-up measures for the following government. The Commission also needs to plan the enshrinement of the victims’ remains and prepare for future exhumation work by instituting regulations or laws and securing the necessary finances and procurement measures. Documentation of investigative records including biannual reports to the National Assembly and the president and the utilization of these materials are essential for future academic research and public promotion of the issues. Relevant laws and systems must also be supplemented, and all documented reports from the Commission’s investigations should be systematically categorized, filed, and stored at an institute such as the National Archives.

The work of the Commission has been focused on these two strong requests from the bereaved families and civil groups. However, the Commission’s efforts to achieve these goals has encountered resistance as a result of the present government’s strong influence on major media outlets. The petitioners are now asking for substantial, visible results of the Commission’s mandates, and the need to respond to those demands remains the duty of Korean law makers and society.

Kim Dong-choon is a former Standing Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, ROK, and professor of sociology, SungKongHoe University, Seoul.

He served the Korean government as a standing commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from December 1, 2005 to December 10, 2009 As a commissioner, he directed the first government investigation of the Korean War massacres since the incidents.

His book, The Unending Korean War, has been translated into German, Japanese, and English. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Kim Dong-choon, “The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 9-5-10, March 1, 2010.

|

This article is part of a series commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the Korean War. Other articles on the sixtieth anniversary of the US-Korean War outbreak are: • Mark Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War. • Steven Lee, The United States, the United Nations, and the Second Occupation of Korea, 1950-1951. • Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas. • Han Kyung-koo, Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On.

Additional articles on the US-Korean War include: • Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism. • Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War. • Sheila • Tim Beal, Korean • Wada Haruki, From • Nan Kim |

Notes

[1] ‘Bodo’ (保道) literally means “caring and guiding.” South Korea’s National Guidance League drew on approaches pioneered under Japanese rule, notably “The League for Servicing the State”, to reeducate and rehabilitate released Korean political dissidents. Later, South Korean prosecutors who had been trained under Japanese rule thought that such an organization would be useful for controlling left-affiliated political dissidents so as to “preserve national security and maintain law and order.”

[2] North Korean troops killed many POWs and rightists when they retreated northward. Paramilitary youth groups and civilians committed state-sponsored political or personal reprisals. Oftentimes, when a family member was killed in a village by a band of paramilitary youths under the authority of occupying forces, relatives would avenge a family member’s death by killing the entire family of their enemy when the attackers eventually retreated. This sort of revenge occurred in every corner of the Korean peninsula during the war.

[3] Some reporters argued that the American CIC ordered the massacre, but this has not been confirmed (Hangeore21).

[4] On the question of U.S. military involvement in Korean civilian massacres see Charles J. Hanley and Martha Mendoza, The Massacre at No Gun Ri: Army Letter reveals U.S. intent; Bruce Cumings, The South Korean Massacre at Taejon: New Evidence on US Responsibility and Coverup. Charles J. Hanley, Sang-hun Choe and Martha Mendoza, The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War (New York: Henry Holt, 2001).

[5] From February 6-9, 1951, when the ROK army’s Eleventh Division was conducting suppression operations against guerrilla remnants in mountainous areas of South Keongsang Province, more than 700 unarmed civilians, including children, women, and elderly, were killed after being suspected of assisting the guerillas. The Guchang incident, was officially recognized by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission among numerous mass killings. See Dong-Choon Kim, The Unending Korean War.

[6] The April 3 Incident was a series of events in which thousands of islanders were killed in clashes between guerilla and government forces. The Jeju branch of the South Korean Labor Party organized an uprising against the American-sponsored rightist government. During the suppression of leftists and guerrillas, nearly 30,000 civilians were killed by National Police, Northwest youth and National Guard. Since the incident occurred during the period of US military government, the operation, which resulted in numerous civilian deaths, was conducted under the sponsorship of U.S forces.

[7] See, “Summary of the Report’s Conclusion”.

[8] The final U.S. Army report on No Gun Ri is available here.The President’s statement is available at The White House statement is on the Web here. Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen’s press conference of January 11, 2001 on the issues is here. Cohen stated, “As a symbol of our deep regret over the tragedy, the United States will erect a memorial in the vicinity of No Gun Ri, which will be dedicated to the innocent Korean civilians who lost their lives during the struggle to preserve the independence of their country.”

[9] The investigation has been repeatedly hampered by lack of cooperation by some government organizations.

[10] Some U.S veterans were angered by the AP report. They retorted, “Every combat veterans knows that the only law during war is to kill or be killed…Not one single American who served in South Korea owes the people of that country an apology for anything” (Lynnita Brown, “The Anguish of U.S Veterans – No Gun Ri”, Korea Herald, October 16,1999).