Gyokusai or “Shattering like a Jewel”: Reflection on the Pacific War

Hiroaki Sato

This past fall I was thinking once again about the intractability of

The examiner, if he was thinking at all, took an action as improbable as the war itself. Yes,

With the annihilation of its 2,500-man force on

Japanese soldiers killed in what is thought

to have been their final charge on

In that light, you might say that the Battle of Iwo Jima (February 19 to mid-March 1945 [5]), about which Clint Eastwood recently made twin films, one from the perspective of the defenders, did not create more deaths among Japanese forces than the Battle of Saipan only because the sulfuric island, one third the size of Manhattan, could not sustain more soldiers. The gyokusai there claimed 21,000 lives (1,000 surviving).

Gen. Kuribayashi Tadamichi, Commander of Japanese forces, Iwo Jima.

Photo touched up to show him as a full general, the rank to which

he was promoted following the gyokusai. When he died, he was

a lieutenant general. For a related article about him, click here.

As a matter of fact, more than a year before the

Prime Minister Gen. Tojo Hideki

The

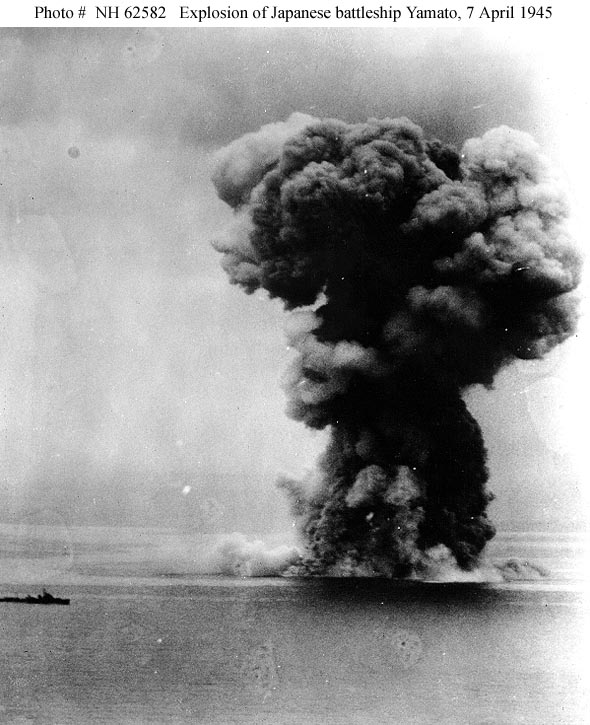

The so-called kamikaze tactic [7] was put into practice during the Battle of Leyte Gulf (October 23-25, 1944).[8] Less than half a year later, when Vice Adm. Ito Seiichi showed reluctance to lead Japan’s last sizable naval sortie, without air cover, to Okinawa on a similar suicidal mission, he was told, “You are requested to die gallantly in advance of the 100-million gyokusai.”[9]

Battleship Yamato running trials

Yamato exploding with Ito on board

Not that the Japanese high command was as callous or as irrational as that from the outset. When they learned of

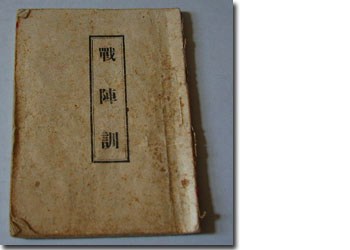

That one notion behind gyokusai, in any event, had to be that of the injunction, “Die, rather than become a POW,” in the Senjinkun, “The Code of Conduct on the Battlefield” – was not exactly what I was thinking when I heard the news of the Okinawan protest rally, but just then I happened to be looking at the injunction and the code, in puzzlement and wonderment.

Tojo Hideki as a young army officer

Issued in January 1941 in the name of Tojo Hideki, then minister of the army, the Senjinkun is known today virtually for that command alone. Because of that, I was doubly surprised when I read the code, along with an account of how it came into being. First, I learned that the Japanese army prepared it in an attempt to counter the widespread collapse of military discipline on the Chinese front: “violence against superior officers, desertions, rape, arson, pillage” – the kind of criminal acts “not seen on the battlefields during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars,” wrote Shirane Takayuki, one of the small group of officers tasked to write it.[12] Shirane was no more than a cavalry lieutenant in the spring of 1939 when he was pulled from the unit confronting Chiang Kai-shek’s army to work on the code, but he had studied philosophy and education at the Imperial University of Kyushu. By then, evidently, the Imperial Rescript to the Soldiers, issued in 1882, had lost its hold. What came to be known as the Nanjing Massacre was just one heinous manifestation of the loss of military discipline and order. So, most of the Senjinkun was devoted to reminding the soldiers, in much greater detail than the rescript, of the importance of upholding the honor of Imperial soldiers. Don’t get drunk, don’t get carried away by lust, do treat non-combatants with kindness, and so on.

What surprised me equally was the command in question, Part II, Article 8. As Shirane put it, after

So I asked my erudite friend at

Commander of the Attu Garrison Col. Yamazaki Yasuyo, in any event, knew exactly what the article meant when he cited it in his wire, on May 29, 1943:

Under ferocious attack by enemy land, sea, and air, the two battalions to the fore were both almost smashed. We have barely been able to sustain this day. I arranged so the wounded and the ill in the field hospital were disposed of, the light ones by themselves, the serious ones by the medics. I made the civilian employees who were noncombatants each take up a weapon, form a unit, both army and navy combined, and follow the attack unit. We had them make a resolve [to die], lest we together suffer the shame of being taken prisoner while alive. It is not that there is no other way; I simply did not wish to sully the soldiers’ last moments. We will carry out a charge with the heroic spirits [of those killed in battle]. [13]

Other than

When seagoing, we might become watery corpses,

mountain-going, corpses for grasses to grow from.

Our wish is to die by our Sovereign’s side

with no looking back.[14]

This song, which was often sung in gatherings to send soldiers off to the front, went on to be known as a “semi-national anthem.”[15]

Another song, which is said to have become the most popular, was also composed in 1937. It said, in its first stanza,

For victory, I pledged,

and gallantly left the country.

Without exploits, I can’t die. . . .

and in the third,

My father, appearing in a dream,

urged me, “Come home in death.”

“Come home in death” (Shinde kaere), to paraphrase, means, “Fight with resolve to die on the battlefield and come home only as a soul.” These words are from “The Song of Bivouac” (Roei no Uta [16]). The lyrics were selected from those submitted by ordinary people in a 1937 newspaper contest. It was the year in which the Nanjing Massacre occurred.

There was another factor. Despite the Geneva Convention, “take no prisoners” was the prevailing practice at the time – not just in the Japanese but in the Chinese military as well. The

“We of course do not expect to return alive” (Seira motoyori seikan o gosezu) – so vowed Ebashi Shinshiro, representing all 25,000 university students, on October 21, 1943, at the ceremony in the Meiji Jingu Gaien stadium, in Tokyo, to send them off to the military.[17] Earlier that year, the Tojo cabinet had raised the eligible draft age to 45 and then abolished draft exemptions for university students. Ebashi was a student at the Faculty of Literature of the Imperial University of Tokyo. Prime Minister Tojo himself gave the farewell speech.

Tojo Hideki was forced out as prime minister following the defeat at

“The mass suicides by deliberate drowning or by rushing futilely against an overwhelming force, were, from the evidence, due to hysteria and despair [rather than “fanatic militarism”],” Helen Mears, in her 1948 book Mirror for Americans: Japan, concluded after cataloguing the myths being created and perpetuated by the New York Times editorialists and others even as their own reporters were saying different things. “There is strong reason to believe that the chief motive in many of the mass suicides was fear of what we would do to them should they surrender,” she went on to note. “Japanese propaganda against us (like ours against them) emphasized our savagery and ruthlessness as a foe. It is significant that we responded to such propaganda by killing more Japanese.”[18]

This brings us to the Battle of Okinawa, the biggest gyokusai as far as the military clashes to which the term is applied are concerned. To quash the Japanese forces defending the fragile archipelago, the

Island people called the American assault “an iron storm” – a series of “shock and awe,” if you will, that lasted for three months. The government structure quickly disintegrated [20], the military command system rapidly splintered. With the idea of death over retreat or surrender prevailing, it would have been a miracle had no Japanese soldiers forced civilians to kill themselves or killed them outright in that chaos and madness.

This substantially expanded version of his column, “Fatal deliverance from an ‘iron storm,’” which appeared in The Japan Times on October 29, 2007, was written for Japan Focus. Posted at

Hiroaki Sato is a translator and essayist in

For other articles on the Battle of Okinawa, gyokusai and Japanese historical memory see

1. Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy,

Aniya Masaaki, The Okinawa Times, and Asahi Shinbun. Translated by Kyoko Selden

2. Shattering Jewels: 110,000 Okinawans Protest Japanese State Censorship of Compulsory Group Suicides, Kamata Satoshi, Shukan Kinyobi translated by Steve Rabson.

Notes:

[1] Hiroaki Sato, “Foreseeing the future – and ignoring it,” Japan Times, January 26, 2004.

[2] Most such words

[3] The Daihon’ei (Imperial Headquarters) announcement cited in the Japanese Wikipedia article on gyokusai, as well as this site on the Attu gyokusai.

[4] Dates of battles and numbers of casualties here are mostly taken from Wikipedia (Japanese and English) and other readily available sources. They can differ from site to site, from one account to another.

[5] Robert Sharrod, reporting from

[6] Ooka Shohei’s Leyte Senki (Chuo Koron Sha, 1974), Vol. 3, p. 288. Ooka, a survivor of the

[7] The proper term was “special attack force” (tokubetsu kogekitai, abbr. tokkotai). The Navy’s initial unit was named Shimpu, the sinified reading of a set of two Chinese characters (Chinese: Shenfeng), but the news accounts soon started giving it in its Japanese reading, Kamikaze, which stuck.

[8] Referring to Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo’s decision to abandon the battle in the Leyte Gulf midway, Ooka observed: “. . . when you really think about it, [Kurita’s failure to follow through the operation plans] corresponds to the inability of Japan as a whole to carry out, in August 1945, the [government’s call for] 100-million gyokusai.”

[9] The words of Vice Adm. Kusaka Ryunosuke, chief-of-staff of the Combined Fleet. See, for example, Yoshida Mitsuru’s life of Ito Seiichi, Teitoku Ito Seiichi no Shogai (Bungei Shunju, 1977), p. 161. Chapter 11 of his book is an attempt to puzzle out the “irrationality” of the action. Yoshida, a survivor of the sinking of the Yamato, wrote Requiem for Battleship Yamato.

[10] Hayashi Shigeru, Taiheiyo Senso (Chuo Koron Sha, 1967; Vol. 25 of Nihon no Rekishi), pp. 340-342. His Majesty’s Aide-de-Camp Jo Eiichiro’s diary records the Showa Emperor’s concern about the fate of

[11] In Bowers’ talk at JETRO New York in the fall of 1995 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of

[12] Senjinkun and Shirane Takayuki’s account cited in full in Hando Kazutoshi’s Showa-shi Tansaku, Vol. 5, pp.143-157.

[13] The Internet site on the Attu gyokusai cited in note 3 carries Yamazaki’s wireless message in its entirety (with a couple of orthographic errors). If the message cited here reproduces the original, Hayashi, quoting it, p. 341, toned it down considerably. His Majesty’s Aide-de-Camp Jo (see note 10), noting the gyokusai in his entry on May 30, 1943, added a parenthetical remark: “In recent times, ‘moving stories’ from the frontline, in many cases, appear [intended] to make up for operational deficiencies.” Jo was killed in battle as captain of the aircraft carrier Chiyoda on October 25, 1944 during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. In his oral recollections of the war, Ooka Shohei said that the Imperial Guard Infantry Regiment, to which he was assigned after being drafted at age 35, despised the Senjinkun in general and Article 8, Part II, in particular. Ooka, Senso (Iwanami Shoten, 2007; originally 1970), p. 60.

[14] Hiroaki Sato, Legends of the Samurai (Overlook Press, 1995), pp. 17-18. Umi Yukaba can readily be heard on the Internet. Click here for a youtube video.

[15] Technically,

[16] Shigure Otowa’s Nihon Kayoshu (Shakai Shiso Sha, 1963). p. 295. Roei no Uta can also be heard on the Internet. Click here for a youtube video.

[17] Hando’s Showa-shi Tansaku, Vol. 6, pp. 257-259.

[18] Helen Mears, Mirror for Americans:

[19] Mears, p. 88.

[20] The daylong bombing involving 1,300 aircraft on October 10, 1944 destroyed 90% of