Editor’s Note:

This is the third article in a three-part special issue titled “Pacific Islands, Extreme Environments” edited by Andrea E. Murray. Murray’s review of a documentary film about the present-day consequences of climate change in Papua New Guinea provides an ethnographic complement to the other two articles in the series: Ilan Kelman’s piece on the challenges of multi-scalar governance in Small Island Developing States, and Tarique Niazi’s inquiry into the fate of so-called “climate refugees” in the Asia-Pacific. In this review, Murray argues for the power and urgency of multimedia research and reporting in places most immediately affected by rising sea levels. The author also questions the pervasive belief that certain dwindling human populations and cultural practices can be “saved” by relocation to a more densely populated mainland.

“What if your community had to decide whether to leave its homeland forever?”

The documentary film There Once Was an Island: Te Henua e Nnoho (On the Level Productions 2010) asks this universal and archetypally complex question of its subjects and its audience. An all too real story about sustainable ecological heritage and cultural continuity is played out on a tiny Pacific atoll called Takū (pronounced Tau’u’u, also known as The Mortlocks). Residents of Takū live on a very small island located 250km northeast of Bougainville Island, an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea (PNG).

Filmmakers Briar March (director) and Lyn Collie (producer) follow the lives and decision-making processes of three people who have grown up on Takū and are struggling to reconcile themselves to the likelihood that their entire Polynesian community of 400 people will be forced to relocate to Melanesian Bougainville, the nearest seat of government. Satty, Endar, and Tēlō each take a different position on the joint problems of relocation and cultural preservation. The film highlights the interplay of post-colonial PNG politics and the expertise of scientist outsiders, showing how this dynamic influences these three individuals’ unique and occasionally conflicting perspectives.http://web.archive.org/web/20200726074428if_/https://player.vimeo.com/video/11017386

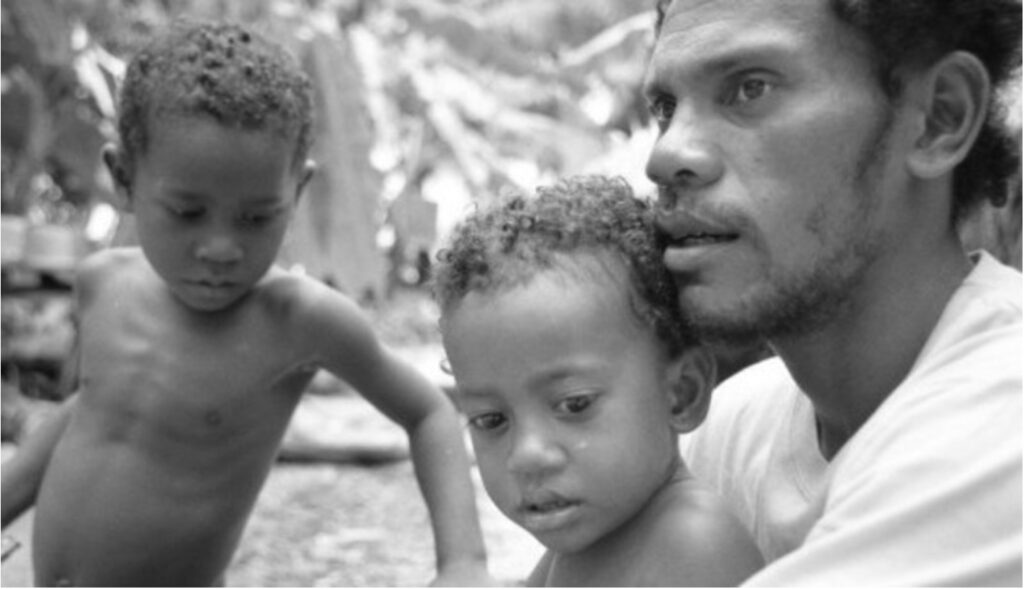

Satty is a thirty-year-old fisherman, farmer, and father of five. Endar is a businesswoman in her late forties who lives fulltime with her husband in the PNG capital of Port Moresby. She returns to Takū, more than thirty years after she first “brought the gospel to this place,” to care for her ailing father. Tēlō is a taro farmer with six children, who describes himself as “a man who’s very keen in my traditions.”

At first glance, it is difficult to imagine a more isolated place in the twenty-first century than Takū: shops, electricity, and regular boat service do not exist here. The Sankamap, a boat that supplies food to the island, comes just two to three times per year and only on short notice. Initially in the documentary, such isolation is presented as a positive thing for cultural and religious continuity:

Separation has helped them retain an egalitarian culture where resources are shared equally, as well as a traditional Polynesian religion which they are the last in the world to practice.

However, themes of change and integration quickly become apparent as the film unfolds. The filmmakers use subtitles because those interviewed speak a mixture of English and the Takū language. The three main protagonists each move fluidly between the two languages, shifting and mixing their words to allow for maximum flexibility in meaning, nuance, and intonation. This linguistic fluidity, combined with community members’ frequent references to Christianity, ongoing island proselytization, and Endar’s discussion of her frequent international business trips, all serve to remind us that the very notion of “isolation” is a myth not held sacred in Takū.

The film is available in two editions: a 60-minute PBS television version and a full-length 80-minute cinema version. The latter is particularly powerful because it provides the space for the filmmakers to explore religious politics related to climate change, as well as the controversial and divisive spread of Christianity on Takū. Vivid scenes of community meetings organized to discuss whether and when to begin the relocation process include the emphatic voices of the faithful. In resistance to calls to evacuate the island a man called Kokoto cries out in English, “God is in control! Hallelujah!” Meanwhile, Endar is shown preaching the Bible to other women and strongly encouraging her own family members to join her in leaving Takū permanently.

The film’s most significant inquiry into the threat of displacement occurs when Endar spearheads an invitation for two New Zealand scientists to board the Sankamap and visit Takū. The Bougainville government hires an oceanographer and a geomorphologist to conduct an extended consultation about the problems residents are experiencing related to rising sea levels. The scientists arrive wearing shorts and t-shirts to begin surveying the island. The researchers canoe out to Tēlō’s giant taro garden, donning extreme mosquito-proofing gear in order to examine the saltwater pollution that is yellowing the farmer’s beloved plants. The cinematography in this sequence is intimate; one hears the piercing, nasal hum of the insects and might even begin to itch.

Later in the film, the scientists appear on a veranda still wearing their college t-shirts on top, but sporting colorful sarongs in lieu of their shorts. Two white foreign scientists offer their knowledge of the island’s topography: They are shown lecturing to the community on erosion and the counter-productiveness of the hand-built sea walls (which impede the natural ability of the shoreline to bolster itself and regenerate) that have been in place for twenty years. An HIV/AIDS public service announcement poster looms in the background as the experts point on a map to the highest ground on the island. This scene reveals the presence of both slow and fast change1 in Takū, foreshadowing just a few of the social problems likely to be magnified by relocation to Bougainville.

One of the most complex and daunting changes faced by community members becomes clear when Satty tells his children: “You will have to learn to work for money.” Outsiders might easily overlook such a fundamental shift in social orientation and economic organization, but for residents of Takū the idea of being paid for their labor is an alien concept. The filmmakers emphasize these kinds of cultural anxieties (what environmental studies scholar Rob Nixon might call “unspectacular” fears)2 against more immediate fears of extreme weather. The film’s exploration of such fears explains why leaving seems so impossible for village elders and even some younger fishermen.

There Once Was an Island documents more than two years of everyday life on Takū. During the second half of filming a major storm sweeps across Papua New Guinea. While the scientists recommend thorough preparations for the approaching waves, little can prevent massive flooding across the island. When the village’s only school floods, one community member laments: “Well, that’s the end of us. No school.” The camera pans symbolically to a waterlogged textbook floating on the school floor, entitled “Government and the People.” Residents repeatedly express their concerns over government inaction: “The government does not do anything!” becomes the post-storm refrain. The Takū people’s widespread disappointment in Bougainville’s inability to support them through this most recent natural disaster, let alone a mass relocation, returns the film’s focus abruptly to the issue of separation and disconnection from mainland PNG.

By the end of the documentary, Satty has decided to stay with his family on Takū. Endar has already left. Tēlō confesses that the storm has changed his mind about staying, and declares that he will now plan to relocate. The film concludes with further commentary about the government’s inaction–a narrative not at all satisfying to the hopeful viewer seeking a happy (or at least happier) ending; but one all too familiar to climate change activists and others faced with rising waters and other extreme weather events in the Pacific Islands and beyond.

Climate change documentaries such as An Inconvenient Truth (2006) provide sweeping global overviews of the effects and long-term implications of rising sea levels and changes in extreme weather patterns across the globe. The Island President (2011) demonstrates the political strategizing and determination necessary to save a low-lying country such as the Maldives (see also Niazi’s article “Ground Zero of Climate Change: Coastal and Island Nations of the Asia-Pacific” in this issue). In contrast, by focusing on three residents of an already disappearing island, There Once Was an Island portrays the complex emotional and spiritual lives of people deciding whether and how to join the diverse population that many anthropologists and environmental scientists have collectively labeled “climate change refugees.” They are confronted with the most important decision of their lives: whether to embrace major geographic, economic, and social change and upheaval for the sake of maintaining some hope of community continuity in a new place. It is a decision that seems foregone among all

The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21 November 30-December 11, 2015) has declared a goal of keeping global warming within the limit of two degrees Celsius compared with the pre-industrial era (c. 1850) at a time of growing international recognition that this will be an impossible feat. COP21 further aims to mobilize 100 billion USD for developing countries by 2020. However, these goals are to be achieved only by consensus among the 196 signatories (195 states and the European Union). While There Once Was an Island has already received the critical acclaim of the Raindance Film Festival and the Jameson Cinefest, the film warrants a second, closer look now that the shortcomings of previous UN Framework Convention on Climate Change meetings have another chance for progress in Paris.

Papua New Guinea has submitted its newest climate action plan for the twenty-first UN session. There Once Was an Island offers a crucial ethnographic reminder that the needs of PNG and other Small Island Developing States for actionable global outcomes continue to rise.

Related APJ:JF Articles

– Andre Vltchek, The Cook Islands and the Pacific Island Nations: Will the Last Person Leaving Please Turn Off the Lights?

– Andre Vltchek, Sinking. Tuvalu and the Pacific Islands in an Age of Global Warming

1 See Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP (2011).

2 Ibid.

3 cf. “The Babushkas of Chernobyl” (2015)