The San Francisco Peace Treaty and Frontier Problems in the Regional Order in East Asia: A Sixty Year Perspective*

Kimie Hara

Sixty years have passed since the signing and enactment of the San Francisco Peace Treaty.1 This post-World War II settlement with Japan, prepared and signed against the background of the intensifying Cold War, sowed seeds of frontier problems that continue to challenge regional security in East Asia. Taking the “San Francisco System” as its conceptual grounding, this article examines these problems in the context of the post-World War II regional international order and its transformation. In light of their multilateral origins, particularly the unresolved territorial problems involving Japan and its neighbors, the article explores ideas for multilateral settlements that could lead East Asia toward greater regional cooperation and community building.

The San Francisco System and the Cold War Frontiers in East Asia

The emergence of the Cold War was a process in which the character of Soviet-US relations was transformed from cooperation to confrontation. With respect to the international order in East Asia, the Yalta blueprint was transformed into the “San Francisco System.” The US-UK-USSR Yalta Agreement of February 1945 became the basis for the post-World War II order in Europe. Following a series of East-West tensions, notably the communization of Eastern Europe and the division of Germany, the Yalta System was consolidated in Europe, and the status quo received international recognition in the 1975 Helsinki agreement. By the early 1990s, however, the Yalta System had collapsed, accompanied by significant changes such as the democratization of Eastern Europe, the independence of the Baltic states, the reunification of Germany, and the demise of the Soviet Union. Since then, many have viewed “collapse of the Yalta System” as synonymous with the “end of the Cold War.”

The Yalta System, however, was never established as an international order in East Asia. The postwar international order was discussed, and some secret agreements affecting Japan were concluded at Yalta. The terms “Yalta System” and “East Asian Yalta System” are sometimes used to refer to a regional postwar order based on those agreements,2 but it was a “blueprint” that would have taken effect only if such agreements had been implemented. By 1951, when the peace treaty with Japan was signed, the premises of the Yalta agreement in East Asia were in shambles. Under the new circumstances of escalating East-West confrontation that had begun in Europe, postwar East Asia took a profoundly different path from that originally planned.

The San Francisco Peace Treaty is an international agreement that in significant ways shaped the post-World War II international order in East Asia With its associated security arrangements, it laid the foundation for the regional structure of Cold War confrontation: the “San Francisco System,” fully reflected the policy priorities of the peace conference’s host nation, the United States (Hara 1999, 517-518).

|

The Signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty |

Along with political and military conflicts, significant elements within the Cold War structure in East Asia are regional conflicts among its major players. Confrontation over national boundaries and territorial sovereignty emerged from the disposition of the defeated Axis countries. Whereas Germany was the only divided nation in Europe, several Cold War frontiers emerged to divide nations and peoples in East Asia. The San Francisco Peace Treaty played a critical role in creating or mounting many of these frontier problems. Vast territories, extending from the Kurile Islands to Antarctica and from Micronesia to the Spratlys, were disposed of in the treaty. The treaty, however, specified neither their final devolution nor their precise limits (see the Appendix at the end of this article), thereby sowing the seeds of various “unresolved problems” in the region.

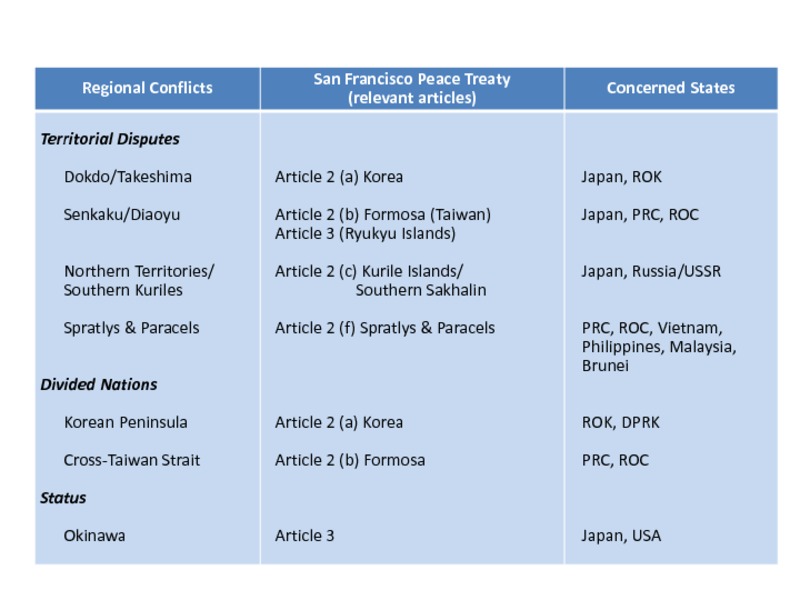

Table 1 shows relations between the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the existing regional conflicts in East Asia, indicating the concerned states in these conflicts. The regional conflicts derived from the postwar territorial dispositions of the former Japanese empire can be classified into three kinds: (1) territorial disputes such as those pertaining to the Northern Territories/Southern Kuriles, Dokdo/Takeshima, Senkaku/Diaoyu, Spratly/Nansha and Paracel/Xisha; (2) divided nations as seen in the Cross-Taiwan Strait problem and the Korean Peninsula;3 and (3) status of territory as seen in the “Okinawa problem.”4 These problems did not necessarily originate solely in the San Francisco Peace Treaty. For example, a secret agreement to transfer the Kuriles and Southern Sakhalin from Japan to the USSR was reached at the Yalta Conference in 1945. However, the problem emerged or received formal expression at San Francisco, since the peace treaty specified neither recipients nor boundaries of these territories. These problems tend to be treated separately or as unrelated. For reasons such as limitations on access to government records and the different ways in which the Cold War and the disputes developed in the region, their important common foundation in the early postwar arrangement has long been forgotten.

|

Table 1. The San Francisco Peace Treaty and Regional Conflicts in East Asia |

Creating “Unresolved Problems”

Close examination of the Allies’ documents, particularly those of the United States, the main drafter of the peace treaty, reveals key links between the regional Cold War and equivocal wording about designation of territory, and suggests the necessity for a multilateral approach that goes beyond the framework of the current disputant states as a key to understanding the origins, and conceptualizing approaches conducive to future resolution of these problems (Hara 2007).

Prior to the final draft of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which was completed in 1951, six years after the Japanese surrender, several treaty drafts were prepared. Early drafts were, on the whole, based on US wartime studies, and were consistent with the Yalta spirit of inter-Allied cooperation. They were long and detailed, providing clear border demarcations and specifying the names of small islands near the borders of post-war Japan, such as Takeshima, Habomai, and Shikotan, specifically to avoid future territorial conflicts. However, against the background of the intensifying Cold War, particularly with the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, the peace terms with Japan changed in such a way as to reflect new strategic interests of the United States, the main drafter of the treaty. Specifically, Japan and the Philippines, soon to be the most important US allies in East Asia, had to be secured for the non-communist West, whereas the communist states were to be contained.

In this context, drafts of the Japanese peace treaty went through various changes and eventually became simplified. Countries that were intended to receive such islands as Formosa (Taiwan), the Kuriles, and other territories disappeared from the text, leaving various “unresolved problems” among the regional neighbors. The equivocal wording of the peace treaty was the result neither of inadvertence nor error; issues were deliberately left unresolved. It is no coincidence that the territorial disputes derived from the San Francisco Peace Treaty – the Northern Territories/Southern Kuriles, Takeshima/Dokdo, Senkaku/Diaoyu (Okinawa5), Spratly/Nansha, and Paracel/Xisha problems – all line up along the “Acheson Line,” the US Cold War defense line of the western Pacific announced in January 1950.

With the outbreak of the Korean War, the United States altered its policy toward Korea and China, which it had once written off as “lost” or “abandoned,” and intervened in their civil wars. However, in order to avoid further escalation of these regional wars, which could possibly lead to a nuclear war or the next total war, the containment line came to be fixed at the thirty-eighth parallel and Taiwan Strait, respectively. These containment frontiers could be perceived as double wedges from the viewpoint of Japanese defense, together with Takeshima and Senkaku/Okinawa islands. On the other hand, viewed from the perspective of US China policy, China’s ocean frontier problems of Senkaku/Okinawa, the Spratlys, and the Paracels may be seen as wedges of containment, together with Taiwan.

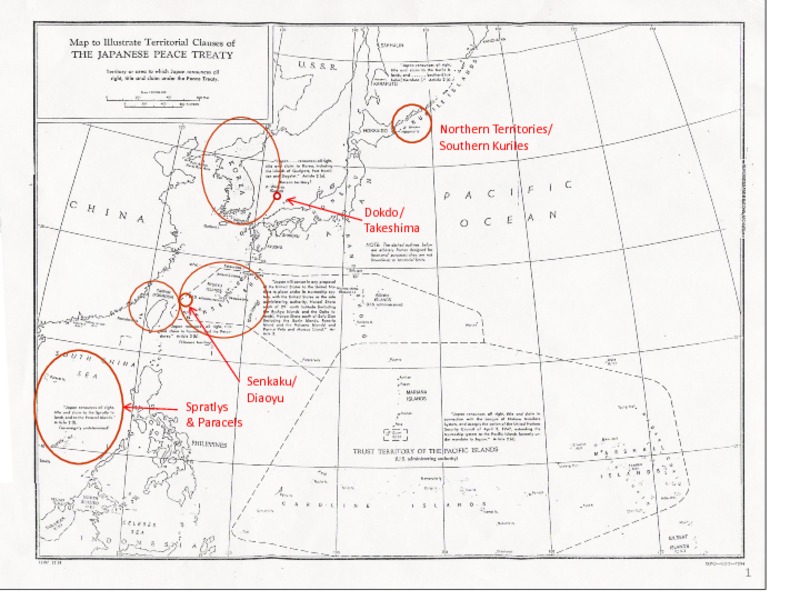

|

Map to Illustrate Territorial Clauses of the Japanese Peace Treaty (Source: United States, 82nd session, SENATE, Executive Report No.2, Japanese Peace Treaty and Other Treaties relating to Security in the Pacific/Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations on Executives, A, B, C and D. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), with related regional conflicts in East Asia marked in red by K. Hara. |

The Spratlys and Paracels disposed of in Article 2 (f) of the peace treaty and located in the South China Sea at the southwest end of the Acheson Line, may be viewed as wedges to defend the Philippines, which was the core of US Cold War strategy in Southeast Asia. Although there were differences of degree, Chinese ownership was considered for these territories in US wartime preparations for a postwar settlement. Their final designation was not specified in the San Francisco Treaty, not simply because it was unclear, but more importantly to make sure that none of them would fall into the hands of China. Disputes over the sovereignty of these islands in the South China Sea existed before the war. However, the pre- and postwar disputes differ in terms of the countries involved and the nature of the disputes—that is, pre-war colonial frontiers reborn as Cold War frontiers in Southeast Asia.6

Multilateral Linkage

These postwar territorial dispositions of the former Japanese empire were closely linked in US government studies and negotiations with the other Allies prior to the peace conference. For example, the Kurile Islands were used as a bargaining chip not only to secure US occupation of the southern half of the Korean peninsula, but also to assure exclusive US control of Micronesia and Okinawa. The deletion of “China” as the designated recipient of Taiwan in the 1950 and subsequent US drafts eventually was extended to all the territorial clauses: that is, no designation or ownership of any of the territories was specified. (Hara, 2007)

With regard to the regional conflicts that stemmed from the Japanese peace settlement, it is noteworthy that there was no consensus among the states directly concerned with these conflicts. The San Francisco Peace Treaty was prepared and signed multilaterally, making the forty-nine signatories the “concerned states.” Except for Japan, however, the major states involved in the conflicts did not participate in the treaty. Neither of the governments of Korea (ROK/DPRK) nor of China (PRC/ROC) was invited to the peace conference. The Soviet Union participated in the peace conference, but chose not to sign the treaty. The result was to bequeath multiple unresolved conflicts to the countries directly concerned and to the region.

Transformation and Contemporary Manifestation of the San Francisco System

During the sixty years since the San Francisco agreement, East Asia has undergone significant transformations. After periods of East-West tension and then their relaxation, such as the Cold War thaw of the 1950s and the détente of the 1970s, the Cold War was widely believed to have ended by the early 1990s. These changes also affected relations among neighboring countries in East Asia, with important consequences (but not solutions) for some lingering territorial problems.

Détente and Cold War Frontiers

In 1955, two years after the signing of the Korean War armistice, peace negotiations began between Japan and the Soviet Union against the background of the Cold War thaw and the new emphasis on “peaceful coexistence”. The following year the two countries restored diplomatic relations and agreed, in a Joint Declaration, to the transfer of the two island groups of Shikotan and Habomai to Japan following conclusion of a peace treaty. Japan, however, was pressed by the United States to demand the return of all four island groups in its so-called Northern Territories. Indeed, the US warned that Okinawa would not be returned to Japan if it abandoned its claims to Kunashiri and Etorofu. US support for the four-island-return formula was made with full knowledge that it would be unacceptable to the Soviet Union (Wada 1999, 255), thus preventing Japan from achieving rapprochement with the Soviet and the communist bloc. Perceiving “détente” as temporary and working to the Soviet Union’s strategic advantage, the US feared that a Japan-Soviet peace treaty would lead to normalization of relations between Japan and communist China. Furthermore, if Japan settled the Northern Territories problem with the Soviet Union, there would be considerable pressure on the United States to vacate Okinawa, whose importance had significantly increased with the US Cold War strategy in Asia especially during the Korean War.

|

The Signing of the Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration (1956) |

The four-island-return policy also reflected Cold War premises in Japan’s domestic politics. It originated as a negotiation strategy devised by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to elicit the two-island concession from the Soviet Union. However, when the two conservative parties, the Liberals and the Democrats, merged in 1955 to form a large ruling party in opposition to the then-strengthening socialist parties, Prime Minister Hatoyama Ichiro accepted the four-island claim as a core policy of the new Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). That claim solidified as enduring government policy throughout the long period of LDP hegemony.

In East Asia, the Cold War developed differently from the bi-polar system in the Euro-Atlantic region. A tri-polar system, US-China-USSR, emerged following the Sino-Soviet split. China had been targeted by the US containment strategy since its intervention in the Korean War. With its nuclear development in 1964, China came to occupy the central position in the Asian Cold War. Considering that the emergence of nuclear weapons fundamentally changed the nature of post–World War II international relations and became the biggest factor for the Cold War, the US-China confrontation became truly “Cold War” in that they did not have a direct military clash. They fought surrogate wars in their satellite states instead.

Sino-Soviet confrontation, on the other hand, while bitter, was initially confined to oral and written communications. However, it escalated into military clashes along the border, especially over ownership of Damansky Island on the Ussuri River in 1969. This Sino-Soviet frontier problem did not derive, and was therefore different, from those conflicts that emerged out of the postwar disposition of Japan. Nevertheless, it came to symbolize the height of Sino-Soviet confrontation that defined the Cold War in East Asia, setting the stage for the dramatic structural transformation of the early 1970s when Sino-US rapprochement occurred. Japan also established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) at that time and terminated its official ties with the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan.

During the détente of the 1970s, Okinawa was returned to Japan, and the focus of the Sino-Japanese territorial dispute shifted to the Senkaku islands, where resource nationalism was accented by the new energy potential discovered in the vicinity of those islands. On the reversion of Okinawa, the US government took “no position on sovereignty” over the Senkakus; it merely returned “administrative rights” to Japan, leaving the dispute to Japan and China. Both Chinese governments (PRC and ROC) then and since have claimed that the islands are part of Taiwan. For Japan, however, because the Senkakus had never been in dispute before, it was a “problem that emerged suddenly” as described in a government pamphlet published in 1972 (Gaimusho johobunka-kyoku, Senkaku-retto ni tsuite, 1972). The ROC government in Taiwan, moreover, held the position that Okinawa was not Japanese territory and opposed its reversion to Japan.

|

Ceremony commemorating Okinawa’s reversion to Japan (1972, Okinawa) |

The Nixon administration entered office with its top diplomatic agenda to normalize relations with China. Inheriting the previous administration’s promise to return Okinawa to Japan, Nixon adopted a policy of “strategic ambiguity” on the Senkaku issue, despite the fact that the US had administered the islands as part of Okinawa (Hara 2007). The rapprochement with China represented US recognition of the political status quo—a shift to an engagement policy rather than an end to the Cold War. Under Nixon, communist China continued to be perceived as a threat to US interests in East Asia and the Pacific, and US bases in Okinawa had to be maintained. The territorial dispute with China helped justify the bases, especially in Japan. Thus, leaving the dispute unsettled, not taking the side of any disputants, and keeping the wedges among the neighboring states met US interests in retaining its presence and influence in the region. Just as the wedge of the Northern Territories problem was set in place with the four-island-return claim between Japan and the Soviet Union during the Cold War thaw of the 1950s, the Senkaku issue was another wedge set in place between Japan and China.7

In the meantime, the “unresolved problems” that shared a common foundation in the San Francisco Peace Treaty continued to fester. In addition to divided China, the newly independent countries—(South) Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei—joined the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. With Taiwan and South Korea not lost to the West, however, the Cold War nature of the Takeshima/Dokdo, Senkaku/Diaoyu, and South China Sea disputes came to be overlaid by other issues, such as nationalism and competition over maritime resources. Furthermore, introduction of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), particularly its rules governing Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and the continental shelf, greatly contributed to complicating these territorial problems, since ownership of the disputed territories could determine the location of the EEZ boundaries.8

|

Competing Claims in the South China Sea (Source) |

Remaining Regional Cold War Structure

In the subsequent period of global détente, from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, the Cold War was widely believed to have ended. Both US-Soviet and Sino-Soviet rapprochement were achieved, and a remarkable relaxation of tension occurred in East Asia where expectations soared for solution of some of the most intractable frontier problems. In the late 1980s, serious deliberations began in Sino-Soviet/Russian border negotiations. The two countries finally completed their border demarcation by making mutual concessions in the 2000s. However, none of the frontier problems that share the foundation of the San Francisco Peace Treaty reached a fundamental settlement. In fact, compared to the Euro-Atlantic region where the wall dividing East and West completely collapsed, the changes that took place in East Asia left intact fundamental divisions. Except for the demise of the Soviet Union, the regional Cold War structure of confrontation basically continued. As of today, twenty years hence and sixty years after San Francisco, in addition to the above-mentioned territorial problems, China and Korea are still divided, with their communist or authoritarian parts still perceived as threats by their neighbors. Accordingly, the US military presence through its hub-and-spokes security arrangements with regional allies, known as the “San Francisco Alliance System,” and associated issues, such as the “Okinawa problem”, continue in this region. Whereas the Warsaw Treaty Organization disappeared and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) lost its anti-communist focus when it accepted formerly communist countries in Eastern Europe as members, there are no indications that the remaining San Francisco Alliance System will embrace North Korea or China.

Nevertheless, in some disputing states, where epoch-making changes associated with the “end of the Cold War” took place, notable policy shifts have occurred. In the Soviet Union (later Russia), the government position on the Southern Kuriles/Northern Territories, once so rigid as to deny that a problem even existed, softened in the 1990s to the extent of recognizing the possibility of the two-island-transfer promised in the 1956 Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration. In Taiwan, as democratization progressed, public opinion and national policies toward the one-China principle diversified. This may be seen in the establishment of the non-Kuomintang (KMT) pro-independence government in 2000 and the return to power of the KMT in 2008, supported by people who favoured a deepening of PRC-ROC economic ties and cooling tensions with the mainland China. However, no fundamental policy change has occurred in the other regional conflicts, particularly the territorial disputes. Each country has solidified its position as a policy norm while constantly repeating the same claim with the result that the issue has become one of face and prestige for the respective governments.

In the sense that the fundamental structure of confrontation remains, the dramatic relaxation seen in East Asia since the late 1980s can be viewed more appropriately as similar to détente rather than the “end” of the Cold War. The relaxation of tension seen in the Cold War thaw in the 1950s and détente in the 1970s in both instances gave way to deterioration of East-West relations. Similar phenomena have been observed in East Asia, such as US-China conflicts after the Tiananmen incident of 1989, military tensions across the Taiwan Strait and in the Korean Peninsula, disruption of negotiations between Japan and North Korea to normalize their diplomatic relations, and political tensions involving Japan and its neighbors over territorial disputes and interpretation of history. Nonetheless, considering that the 1975 Helsinki Accords recognised the status quo of the (then) existing borders in Europe, the political status quo in East Asia, where disputes over national borders continue, may not have reached the level of the 1970s détente in Europe.9

Deepening Interdependence in Economic and Other Relations

Whereas countries and peoples in East Asia have been divided by politics, history, and unsettled borders, they nevertheless have become closely connected and have deepened their interdependence in economic, cultural, and other relations. With China’s economic reform, it may be possible to consider that regional Cold War confrontation began to dissolve partially in the late 1970s.10 The economic recovery and transformation of East Asian countries for the last sixty years from the ruins of war are in fact remarkable. Beginning with Japan in the 1950s, followed by the so-called newly industrializing economies (NIEs)11 in the 1970s and 1980s, and now with China’s rise, East Asia, with the exception of North Korea, has become the most expansive center in the world economy. Economy is indeed the glue connecting the regional states.

Economic-driven multilateral cooperation and institution building have also developed notably in East Asia with the creation of multiple institutions, especially since the 1990s. A broad regional framework has emerged in the Asia-Pacific, building on such foundation as the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). In the wake of the global-scale economic crises of 1997 and 2008, additional multilateral forums involving China (PRC), Japan, and South Korea (ROK) have emerged, such as ASEAN+3 (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations plus the PRC, Japan, and the ROK) and the PRC-Japan-ROK Trilateral Summit, adding new dimensions to an emerging regionalism. In the meantime, Russia, which joined APEC in 1998, is also increasing its presence by enlarging its investment in its Far East region and deepening its economic ties with its neighboring states in East Asia. Vladivostok is hosting APEC meetings in 2012, which may further facilitate strengthening Russia position in the region.

Along with strengthening economic ties, more wide-ranging areas of cooperation are developing among East Asian countries. Ken Coates points out that universities have the potential to be a key force for regional integration. “The emergence of East Asian power is, at least in part, the result of thirty years of investment and commitment to universities, colleges and research” (Coates 2010, 305). In the past, Western countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom were major foreign destinations for Asian students to learn advanced knowledge and technologies. Statistics on international student mobility show much greater movement within East Asia in recent years. The increasing exchange of students and intellectual communities has the potential to reduce barriers in the region and accelerate the process of East Asian integration.

Expanded regional cooperation and increased interaction have paved the way for confidence-building measures (CBMs) among neighboring states. Progress in CBMs since the 1990s at both governmental and nongovernmental levels constitutes a leap beyond the Cold War era, particularly in non-traditional security areas such as the environment, food, energy, terrorism, and natural disasters. There have also been significant developments in conflict management or cooperation concerning disputed areas such as fishery and continental shelf, as well as hotline agreements. Multilateral cooperation has been actively pursued in diplomatic and security dialogues using forums such as APEC, the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), ASEAN+3, the Six Party Talks, the East Asian Summit, and the PRC-Japan-ROK Trilateral meetings. Nevertheless, while activities have multiplied, the depth of integration pales compared with those of Europe. While the European Community (EC) of the Cold War era has long since evolved into the European Union (EU), even the idea of an “East Asian Community” (not an “East Asian Union”) is still a future aspiration. As yet, the East Asian countries do not have relations of sufficient mutual trust. Their countries and peoples are strongly connected economically, but they remain divided politically, and are still in dispute over “unresolved problems”, including those over territorial sovereignty and borders.

Thus, even though global waves of “post–Cold War” transformations in international relations such as globalization and regionalism have reached East Asia, they do not necessarily deny the remaining structure of confrontation founded in San Francisco in 1951. The end of the Cold War is not yet history, but is yet to come in East Asia.

Envisioning a Multilateral Settlement

The Cold War has sometimes been called the period of “long peace” inasmuch as the balance of power was relatively well maintained and international relations were rather stable (Gaddis 1987). Such was the case in the US-Soviet and European context, but in East Asia many regional conflicts emerged, and international relations became highly unstable. These unstable circumstances continue today, even though relations between neighbors may have improved. Many possibilities exist for the resurgence of conflicts. Although efforts to enhance CBMs and prevent the escalation of conflicts are certainly important, CBMs alone do not lead to fundamental solutions. The road to peace ultimately requires removal of principal sources of conflict. Yet is it really possible to solve the problems that have been ongoing for such a long time? If so, different and more creative approaches may be necessary. Such may be found in multilateral efforts that reflect the historical experience and new reality of international relations. This section explores some ideas for the future resolution of the frontier problems, particularly the territorial disputes between Japan and its neighbors.

Why Multilateral?

Historical experience suggests that it is extremely difficult to solve long-running problems bilaterally or through negotiations confined to the nations directly involved in the disputes. This may be particularly true of contentious territorial issues. In fact, some, if not all, of these issues may be insoluble as long as they remain within such traditional bilateral frameworks. Having been mutually linked and multilaterally disposed of in the context of the post–World War II settlement, it seems worthwhile to return to their common origin and consider their solution within a multilateral framework.

In a multilateral framework, mutually acceptable solutions not achievable within a bilateral framework may be found by creatively combining mutual concessions. Such an approach might avoid the impression of a clear win-lose situation and an international loss of face. Furthermore, multilateral international agreements tend to be more durable than bilateral ones. The more participating states there are, the stronger restraint tends to be, and the greater the possibility that a country in breach will be internationally isolated. Obtaining wide international recognition for settlements is, therefore, desirable.

In the recent context of regionalism, multilateral problem solving may contribute to regional community building and integration, namely toward building an East Asian Community and possibly even a regional union. Resolution of long-standing issues will not only help remove political barriers to regional integration, but may also help promote the growth of regional identity, thereby reducing the relative importance of borders. Resolution of the territorial disputes may be sought in this broader context as well.

Possible Frameworks: ICJ, Trilateral, Four Party, or Six Party?

What kind of multilateral framework is appropriate for dealing with these regional conflicts in East Asia? Today the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is available for dealing with international disputes. Bringing cases to the ICJ, if disputes arise, was also suggested in the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Japan, in fact, proposed in 1954 and 1962 that the case of Takeshima/Dokdo be brought to the ICJ, but South Korea refused. Bringing individual cases into such a multilateral framework is certainly extremely difficult. Through over half a century of disputes, the positions of all parties are widely known and mutually exclusive. Any settlement produced by an international organization, even within a multilateral framework, could be viewed as a win-lose situation, with a danger of international loss of face. Third-party arbitration runs the same risk of a win-lose situation and potential loss of face—if cases are dealt with individually.

However, if at least some of these issues were examined or negotiated together within a multilateral framework, or along with a number of other outstanding issues, the circumstances might be different. An existing framework may be used, or a new framework may be created. For example, Japan’s territorial and maritime disputes with its neighbors—Russia, Korea, and China—may be brought to the ICJ together for joint examination and collective settlements. If not the ICJ, some existing regional framework may be used. For example, the Japan-ROK-PRC trilateral meetings since the December 2008 Dazaifu summit may have potential for conflict resolution. This trilateral group might add Russia, creating a four-party framework that would consist of Japan and its dispute counterparts that were not signatories to the San Francisco Peace Treaty. This framework would include Russia and China, the two powers that successfully negotiated and achieved demarcation of the world’s longest border.

The Six Party Talks, with the United States and the DPRK added to the four parties mentioned above, offer another potentially useful framework. US participation may make sense, considering its role in preparing the San Francisco Peace Treaty as well as its continuing presence and influence in the region. The Six Party Talks have been the particular forum for negotiating issues surrounding the North Korean nuclear crisis. This issue is essentially about survival of the North Korean regime, which has been trying to obtain cooperation and assurances from the United States and neighboring countries. Originally, this problem developed from the question to which country or government Japan renounced “Korea”. Like Takeshima/Dokdo and other conflicts in East Asia, it was an “unresolved problem” originating from the postwar territorial disposition of Japan. The Six Party framework, although stalled since 2008, may also have the potential to develop into a major regional security organization in the North Pacific in the future.

When it comes to detailing the conditions or concrete adjustments necessary for a settlement, multilateral negotiations may be supplemented by parallel discussions in a bilateral framework. If initiating such negotiations at the formal governmental (Track I) level is difficult, they may be started from, or combined with, more informal (Track II) level.

In considering such negotiation frameworks, a key question to be addressed may be whether US involvement would work positively or negatively for the solution of these conflicts. If the United States perceives their settlement as inimical to its strategic interests, its involvement would become detrimental. Historically, US Cold War strategy in the San Francisco Peace Treaty gave rise to various conflicts among regional neighbors. The United States also intervened in the Soviet-Japanese peace negotiations to prevent rapprochement in the mid-1950s. In the post–Cold War world, where the Soviet Union no longer exists and China has become a large capitalist country, however, the Cold War strategy to contain communism no longer seems valid.

Nevertheless, the United States may perceive regional instability as beneficial to its strategy, as long as it is manageable and does not escalate into large-scale war. It is precisely “manageable instability” that helps justify a continued large US military presence in the region, not only enabling the United States to maintain its regional influence, but also contributing to operations farther afield, such as in the Middle East. A solution to East Asian regional conflicts would alter the regional security balance and accordingly influence regional security arrangements, particularly the San Francisco Alliance System. Just as was the case during the Cold War détente and after the so-called “end of the Cold War”, considerable pressure would arise for the United States to withdraw from, or reduce its military presence in, the region. This would very likely affect its bases in Okinawa, which currently remains the most contentious issue in US-Japan relations. Although an accommodation between Japan and its neighbors is preferable for regional stability, it would not be viewed as beneficial by US strategists if it was perceived as likely to reduce or exclude US influence. Thus, continued conflicts among regional countries may still be seen as meeting US interests.

On the other hand, if the United States perceives the resolution of disputes as being beneficial, its constructive involvement would become a strong factor in ending them. How might the United States benefit from resolving these disputes? A peaceful and stable East Asia, a region in which the United States is heavily involved in economic development, trade, culture, and other arenas, surely is a significant US interest. Reduction of its military presence would contribute to cutting US defense spending at a time of heavy budget pressure. US leaders may also be convinced of the value of conflict resolution if it can maintain its influence and presence through security arrangements—for example, a multilateral security organization based on the Six Party or other frameworks. The continuing presence and expanded mission of NATO since the Cold War and after the establishment of the EU may present a notable precedent.

Settlement Formula: Mutual Concessions and Collective Gains

What kinds of concrete settlements can be envisioned in a multilateral framework? A workable settlement formula would include mutual concessions and collective gains. Each party would have to make concessions, but the gains would potentially be far greater than what they conceded if the region is viewed as a whole.

The following are preliminary considerations with hypothetical examples that may be used as bases for further deliberation. In the trilateral framework, Japan might, for example, make a concession to Korea with respect to Dokdo/Takeshima, while China might make a concession to Japan over Senkaku and Okinawa.12 Then, in exchange for these, Korea might offer concessions over the naming issues of its surrounding seas by withdrawing its claim for “East Sea,” “West Sea,” and “South Sea” and accepting “Sea of Japan,” “Yellow Sea,” and “East China Sea,” respectively, as their names.

In the four-party framework, with Russia added to these three countries, Japan and Russia might make mutual concessions and return to the two-island transfer of the 1956 Joint Declaration—an international agreement ratified at the time by their legislatures. This might appear as a win-lose situation in a bilateral framework, but such an impression would be softened by combining the agreement with other territorial settlements and additional conditions. These are basically recognition of the status quo, except for the Russia-Japan islands transfer. Accomplishing that much would at least bring the situation up to the level of the 1975 Helsinki Accords in Europe.

These arrangements may also be combined with mutual concessions in maritime border negotiations, including EEZ delimitations. As mentioned earlier, introduction of UNCLOS has greatly contributed to complicating territorial problems. Yet it may provide opportunities for dispute settlement by opening up more options for a combination of concessions. For example, instead of using Dokdo (Korea) and Oki (Japan) as base points to draw the EEZ line, Dokdo could be used as the base point for both Korea and Japan, and their median line could be drawn along the 12-nautical-mile territorial waters of Dokdo. The logic here is that the median line would be drawn in ways favorable to Japan in exchange for its recognition of Takeshima/Dokdo as Korean territory. A similar arrangement may be made for Senkaku/Diaoyu, with the islands used as the base point of both Japan and China for their EEZ. Furthermore, it may be possible to link these problems with other “settlements of the past”, including non-conventional security issues. Such mutual concession could pave the way for reducing tensions and greater cooperation in multiple areas with mutual benefits for all parties.

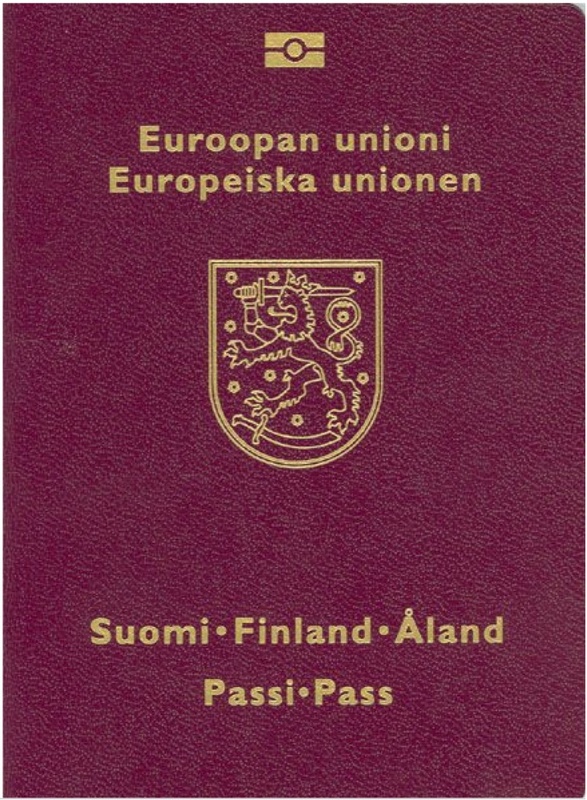

Other settlements might include the demilitarization, international autonomy, or joint development of disputed islands. For those, a historical precedent of conflict resolution in northern Europe—the 1921 settlement of the Åland islands dispute—provides useful lessons, particularly for the Northern Territories/Southern Kuriles where consideration should be given to the residents of the islands (Hara and Jukes 2009). The Åland Settlement, which was achieved in a multilateral framework under the League of Nations, featured settlement of a border dispute through mutual concessions and collective gains. The formula was so mixed that the decision on the islands’ ownership could not be interpreted in the usual win-lose terms. The settlement was also positive-sum for all parties, including the residents of the islands. Finland received sovereignty over the islands, Åland residents were granted autonomy combined with guarantees for the preservation of their heritage, and Sweden received guarantees that Åland would not constitute a military threat. The settlement also contributed to the peace and stability of northern Europe as a whole. The majority of Ålanders originally wanted to reunite with Sweden, and thus were dissatisfied with the settlement. However, as a result of the settlement, Ålanders enjoyed various benefits and special international status, including passports with inscription “European Union—Finland—Åland.” If these innovative arrangements had not been made and Åland had been returned to Sweden, it might well have become merely a run-down and depressed border region, or a military frontier area—quite a different situation from today. The Åland Settlement presents an attractive model of conflict resolution.

|

Front cover of a biometric passport issued to Ålanders. The words “European Union”, “Finland” and “Passport” are written both in Finnish and Swedish, but Åland is only in Swedish (Finish: Ahvenanmaa). |

The Åland model, however, cannot be applied to the Northern Territories/Southern Kuriles dispute or any other regional conflicts in East Asia “as is.” The model must be creatively modified to be applicable. For example, the Northern Territories/Southern Kuriles, Dokdo/Takeshima, and Diaoyu/Senkaku might all be demilitarized. Also, rather than placing them under a local government jurisdiction, some or all of these territories could become a special administrative region with autonomy in politics, economy, culture, and environment. Moreover, such arrangements may be guaranteed not only by the governments directly concerned, but also in a wider international framework.13

Preparing Ideas for the Future

The San Francisco Peace Treaty was, after all, a war settlement with Japan. Therefore, it may make sense for Japan to take the initiative in solving the “unresolved problems” derived from that treaty. Final settlement will require political decisions. Unless politics, and not bureaucracy, can predominate in policymaking, the territorial problems will remain deadlocked. At present, however, political conditions may not be so favorable for resolving these disputes. Given the criticism that political leaders face, any concession by Japan or the disputant countries is likely to be seen as a humiliating setback. No Japanese politician seems strong enough to withstand such criticism. Yet, as with many international disputes, time may again present opportunities for solutions.

Togo Kazuhiko, a former senior diplomat of Japan who played a leading role in the negotiations with the USSR/Russia from the late 1980s to 2001, identified five opportunities to settle the Northern Territories problem (Togo 2007). Yet none of the proposals presented then was mutually acceptable to both Japan and Russia. Scholars may be able to contribute to such diplomatic efforts by providing ideas and information, to prepare for the time when an opportunity does present itself again.

The years 2011 and 2012 mark the sixtieth anniversary since the signing and the enactment of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. In East Asia, a span of sixty years has special meaning, signifying the end of one historical cycle and the beginning of a new spirit and a new era. It may be a good opportunity to remember the early post–World War II arrangements and re-examine the policies or policy norms that were solidified during the Cold War period.

Kimie Hara (email) is the Director of East Asian Studies at Renison University College, the Renison Research Professor and a management team member of the Japan Futures Initiative at the University of Waterloo (Canada), and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. Her books include Northern Territories, Asia-Pacific Regional Conflicts and the Aland Experience: Untying the Kurillian Knot (with Geoffrey Jukes), “Zaigai” nihonjin kenkyusha ga mita nihon gaiko (Japanese Diplomacy through the Eyes of Japanese Scholars Overseas), Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific: Divided Territories in the San Francisco System, Japanese-Soviet/Russian Relations since 1945: A Difficult Peace.

* This study builds on the author’s earlier research and publications, and accordingly contains some overlapping contents. The author would like to thank the Japan Foundation, the Northeast Asian History Foundation, the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University, and the International Institute for Asian Studies, for grants and fellowships that supported relevant research, as well as the following individuals for valuable suggestions; Mark Selden, Yongshik Bong, Kazuhiko Togo, Lezek Buszynski, Rouben Azizian, John Swenson-Wright, Charles Armstrong, Linus Hagström, and Marie Söderberg.

Recommended citation: Hara, Kimie, “The San Francisco Peace Treaty and Frontier Problems in The Regional Order in East Asia A Sixty Year Perspective,” The Asia- Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 17, No. 1, April 23, 2012.

APPENDIX:

Excerpt from the San Francisco Peace Treaty

CHAPTER II: Territory

Article 2

(a) Japan, recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title and claim to Korea, including the islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton and Dagelet.

(b) Japan renounces all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores.

(c) Japan renounces all right, title and claim to the Kurile Islands, and to that portion of Sakhalin and the islands adjacent to it over which Japan acquired sovereignty as a consequence of the Treaty of Portsmouth of September 5, 1905.

(d) Japan renounces all right, title and claim in connection with the League of Nations Mandate System, and accepts the action of the United Nations Security Council of April 2, 1947, extending the trusteeship system to the Pacific Islands formerly under mandate to Japan.

(e) Japan renounces all claim to any right or title to or interest in connection with any part of the Antarctic area, whether deriving from the activities of Japanese nationals or otherwise.

(f) Japan renounces all right, title and claim to the Spratly Islands and to the Paracel Islands.

Article 3

Japan will concur in any proposal of the United States to the United Nations to place under its trusteeship system, with the United States as the sole administering authority, Nansei Shoto south of 29º north latitude (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands), Nanpo Shoto south of Sofu Gan (including the Bonin Islands, Rosario Island and the Volcano Islands) and Parece Vela and Marcus Island. Pending the making of such a proposal and affirmative action thereon, the United States will have the right to exercise all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction over the territory and inhabitants of these islands, including their territorial waters.

Source: Conference for the Conclusion and Signature of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, San Francisco, California, September 4–8, 1951, Record of Proceedings, Department of State Publication 4392, International Organization and Conference Series II, Far Eastern 3, December 1951, Division of Publications, Office of Public Affairs, p. 314.

References

Coates, Ken. 2010. “The East Asian University Revolution: Post-Secondary Education and Regional Transformation.” In Kimie Hara, ed., Shifting Regional Order in East Asia—Proceedings. Keiko and Charles Belair Centre for East Asian Studies, Renison University College, University of Waterloo, Pandora Press, workshop, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, pp. 305–331.

Gaddis, John Lewis. 1987. The Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2000. The United States and the Origins of the Cold War. New York: Columbia University Press. First edition, 1971.

Gaimusho johobunka-kyoku, Senkaku-retto ni tsuite (The Public Information and Cultural Affairs Bureau, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, About the Senkaku Islands), 1972. At www.worldtimes.co.jp/gv/data/senkaku/main.html.

Gallichio, Marc S. 1988. The Cold War Begins in Asia: American East Asian Policy and the Fall of the Japanese Empire. New York: Columbia University Press.

Halliday, Fred. 1983. The Making of the Second Cold War. London: Verso.

Hara, Kimie. 1998. Japanese-Russian/Soviet Relations Since 1945: A Difficult Peace. London: Routledge.

———. 1999, “Rethinking the ‘Cold War’ in the Asia-Pacific”, The Pacific Review, Vol.12, No.4, pp. 515-536.

———. “50 years from San Francisco: Re-examining the Peace Treaty and Japan’s Territorial Problems”, Pacific Affairs, Fall 2001, pp. 361-382.

———. 2006. “Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific: The Troubling Legacy of the San Francisco Treaty.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, September, at http://japanfocus.org.

———. 2007. Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific: Divided Territories in the San Francisco System. New York: Routledge.

———. and Geoffrey Jukes, eds. 2009. Northern Territories, Asia-Pacific Regional Conflicts and the Aland Experience: Untying the Kurillian Knot. New York: Routledge.

Hosoya, Chihiro. 1984. Sanfuranshisuko kowa eno michi (The Road to the San Francisco Peace). Tokyo: Chuokoron-sha.

Iriye, Akira. 1974. The Cold War in Asia: A Historical Introduction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nagai, Yonosuke. 1978. Reisen no kigen: sengo ajia no kokusai kankyo (Origin of the Cold War: International Environment of Postwar Asia). Tokyo: Chuokoron-sha.

Soeya, Yoshihide. 1995. Nihon gaiko to chugoku 1945–1972 (Japanese Diplomacy and China 1945–1972). Tokyo: keiko gijuku daigaku shippan-kai.

Togo, Kazuhiko. 2007. Hoppo ryodo kosho hiroku: ushinawareta gotabi no kitai (The Secret Record of Northern Territories Negotiations: Five Missed Opportunities). Tokyo: Shincho-sha.

Wada, Haruki. 1999. Hoppo ryodo mondai: rekishi to mirai (The Northern Territories Problem: History and Future). Tokyo: Asahishimbun-sha, 1999.

Notes

1 The Treaty of Peace with Japan (commonly known as the San Francisco Peace Treaty) was officially signed on September 8, 1951 in San Francisco, and came into force on April 28, 1952.

2 For example, see Iriye 1974, 93–97, and Soeya 1995, 33–38.

3 With regard to the treatment of Formosa (Taiwan), the peace treaty alone did not divide China. However, by leaving the status of the island undecided, it left various options open for its future, including possession by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or the Republic of China (ROC), or even its independence. The peace treaty also left the final designation of “Korea” unclear. Although “Korea” was renounced and its independence recognized in the treaty, no reference was made to the existence of two governments in the divided peninsula, then at war with each other. There was then, and still is, no state or country called “Korea”, but two states, the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north.

4 Okinawa (the Ryukyus), together with other Japanese islands in the Pacific, were disposed of in the Treaty’s Article 3 (See APPENDIX). This article neither confirmed nor denied Japanese sovereignty, but guaranteed sole US control — until such time that the US would propose and affirm a UN trusteeship arrangement — over these islands. “Administrative rights”, if not full sovereignty, of all the territories specified in this article were returned to Japan by the early 1970s, without having been placed in UN trusteeship. Yet long after the “return”, the majority of US forces and bases in Japan remain concentrated in Okinawa.

5 The territorial problem between Japan and China was originally over Okinawa. Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China (ROC), representing “China” at the UN, demanded the “recovery” of Ryukyu/Okinawa in the early postwar years. Meanwhile, the US leadership saw possibility of ROC to be “lost” to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as reflected in the Acheson Line of January 1950 excluding Taiwan from the US defense area. Through ROC agency, therefore, the peace treaty left the dispute between Japan and “China,” whose continental territory had become communist. On the other hand, the PRC, soon after its establishment in 1949, supported Okinawa’s reversion to Japan, which was, however, nothing but political propaganda. The PRC was pursuing policy priority of the time, i.e., removal of US military bases from Okinawa to “liberate” neighboring Taiwan, and friendly relations with (i.e., expansion of communist influence to) Japan. For the PRC, if all those areas could fall into the communist sphere of influence, it mattered little to which country they belonged. Reversion to the ROC’s, or China’s traditional, position on Okinawa was a problem that could be dealt with after recovering Taiwan. (This occurred to North Vietnam, which inherited South’s claim for the Spratlys and the Paracels after their reunification in the 1970s.) At this point, the US removal from Okinawa was simply more important than ownership of the islands.

6 Before World War II the countries in dispute in the South China Sea were China and two colonial powers, Japan and France. After the war Japan and France withdraw, and the islands came to be disputed by the two Chinas and the newly independent neighboring Southeast Asian countries. For details on the disposition of the Spratlys and Paracels in the San Francisco Peace Treaty, see Hara 2007, Chapter 6.

7 A second Japan-USSR summit meeting held in 1973, after an interval of seventeen years, also failed to resolve the territorial problem or a final peace treaty. Meanwhile, the US military continued to stay in Okinawa.

8 See United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea, Agreement Relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention, in particular Part V for EEZ and Part IV for continental shelf.

9 One exception to this may be the Korean Peninsula. Both North and South Korea joined the United Nations in 1991, as had both East and West Germany in 1973. While the Cold War status quo was receiving international recognition on the Korean Peninsula in East Asia, German reunification, symbolizing the end of the Cold War in Europe, had already taken place in 1990.

10 However, there was then no general recognition that only the US-China Cold War ended and the US-Soviet Cold War continued.

11 These are South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, also called the Four Asian Tigers.

12 Since the ROC government in Taiwan has not formally withdrawn its claim to Okinawa/Ryukyu, the PRC could disavow it or promise not to revive it.

13 For details, see Hara and Jukes 2009, pp. 119–124.