Gaijin Hanzai Magazine and Hate Speech in Japan:

The newfound power of Japan‘s international residents

Arudou Debito

A recent event making headlines worldwide was the publication of GAIJIN HANZAI URA FAIRU (The Underground Files of Gaijin Crime). This magazine, which went on sale at major Japanese bookstores and convenience stores nationwide, depicts foreigners as “dangerous” and “evil”. Despite Japan‘s lack of a legal framework, or a civil society capable of curbing hate speech, activists managed to have the magazine removed from stores and put out of circulation. This report shows how non-Japanese residents in Japan (a disparate group with few things in common–not even a language) successfully pushed for their rights in a case ignored by the Japanese media. Utilizing the power of the Internet to organize a boycott of magazine outlets, “Newcomer” [1] residents and immigrants demonstrated their strength as a consumer bloc for what is probably the first time in Japan‘s history. This is the report of a participant observer.

Publication of “Gaijin Hanzai”

In the last week of January 2007, Eichi Publishing Inc of Shibuya, Tokyo, a middle-tier publisher specializing in popular culture (including Korean drama stars and hip hop music) and pornography, released a 128-page “mook” (magazine-book) entitled “GAIJIN HANZAI URA FAIRU” (The Underground Files of Gaijin Crime). Printed in full color on high-quality glossy paper, the content of Gaijin Hanzai warrants close examination (scanned and available in full online , as its sensational treatment of foreigners made this issue [2] into a case of hate speech.

As defined under United Nations treaties to which Japan is signatory (emphases added):

- [States parties] (a) Shall declare an offence punishable by law all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin, and also the provision of any assistance to racist activities, including the financing thereof. (International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Article 4. Effected by Japan in 1996.)

- “Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law” (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 20. Effected by Japan in 1979.)[3]

However, Japan still has no laws or official guidelines regarding “hate speech”, particularly towards Japan‘s ethnic minorities and international residents. As the Japanese government stated to the United Nations (October 2001):

“[T]he concept provided by Article 4 may include extremely wide-ranging acts both in various scenes and of various modes. Therefore, to regulate all of them by penal statute exceeding the existing legislation is liable to conflict with guarantees provided by the Constitution of Japan such as freedom of expression, which severely requires both necessity and rationality of the constraint, and the principle of the legality of crimes and punishment, which requests both concreteness and definiteness of the scope of punishment. For this reason, Japan decided to put reservation [sic] on Article 4 (a) and (b) [of the ICERD].”[4]

In other words, Japan has opted out of implementing the treaty due to Constitutional concerns about freedom of expression and the difficulty of assessing punishment. This means that Gaijin Hanzai, as long as it did not target people by name as individuals (tokutei no kojin–falling foul of civil laws governing defamation of character (meiyo kison) [5]) could be published without legal reprisal. However, it would clearly test the boundaries of language inciting discrimination, hostility, and hatred.

Gaijin Hanzai’s Contents

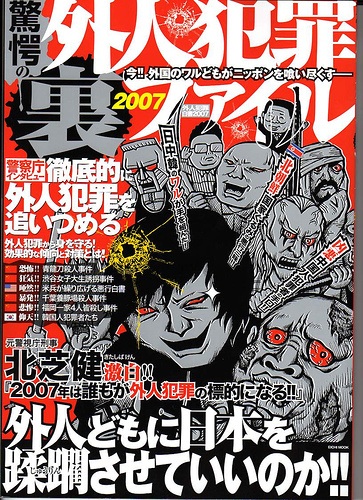

From the very cover, Gaijin Hanzai‘s first impression is indelible: Crazed-looking faces of killers, shooting bullet holes in the cover, drawn with ethnic caricature. Center stage is what appears to be a slitty-eyed member of the Chinese Mafia, followed by a Jihadist, then generic white and black people, with caricatures of both North and South Korean leadership bringing up the rear. These characters face the reader, carry weapons, and are in attack mode.

Cover of Gaijin Hanzai Ura Fairu

Along with a sidebar listing criminality by country (flags included), the cover headlines interviews with the National Police Agency (“thoroughly cornering down gaijin crime”: tettei teki ni gaijin hanzai o oitsumeru), and with ex-police officer and “crime expert” Kitashiba Ken (“Everyone will become a target of ‘gaijin crime’ in 2007!!” (2007 nen wa dare mo ga gaijin hanzai no hyouteki ni naru!!)) The take-home message at the bottom: “SHOULD WE LET THE GAIJIN VIOLATE JAPAN??”(gaijin domo ni nihon o juurin sasete ii no ka!!)

This is clearly aiming to incite alarm in the readership towards non-Japanese, as if “gaijin crime” is the main element of crime in Japan (according to NPA statistics, it is not [6]). Moreover, the use of the word gaijin (a housou kinshi kotoba, or word not permitted for official broadcast in the media) already shapes the debate. Whenever official NPA statistics for foreign crime are quoted within the mook, the official word for it (gaikokujin hanzai) is used. But whenever there is any analysis or comment, gaijin generally becomes the rhetorical currency.

Conclusion: From the very cover, there is no attempt to strike a balance or avoid targeting, alarmism, or sensationalism. The rest of the book continues in this vein

Glossy Photos of Blood and Violence Organized by Nationality

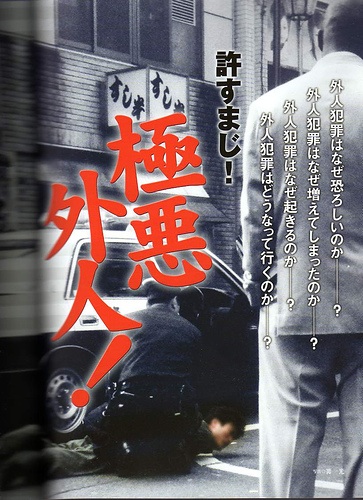

From page one, the magazine accepts and promotes the assumption that foreigners cause more crime than Japanese: “Why is gaijin crime frightening? Why is it rising? [7] Why is it happening?” The text is illustrated with a photo of a gaijin splayed out on the sidewalk by police. The headline, in blood-red: “EVIL FOREIGNER! (gokuaku gaijin!), followed by, “WE CANNOT ALLOW THIS TO HAPPEN!”(yurusu maji!)

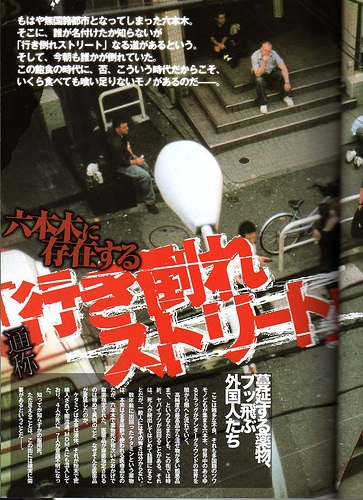

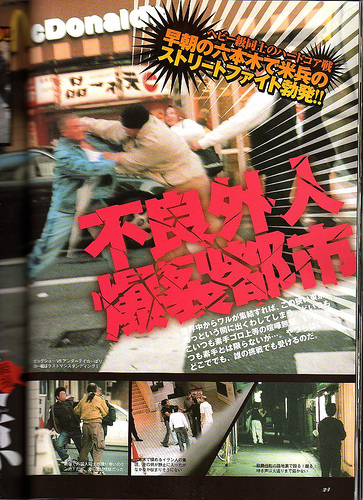

The next pages develop a case for Tokyo as a “Lawless Zone” (fuhou chitai, but the words denjarazu zon in katakana are also included in the headline), listing up the allegedly anarchic areas of Shibuya, Shinjuku, and Roppongi. Often categorized by country or race (China, South Korea, Iran, Brazil, Philippines, black people…) and crime (stabbing, smuggling, kidnapping, attempted murder, assault, petty theft, gangland whacks, youth gangs…), Gaijin Hanzai contains captions creatively interpreting the full-color scenes of blood and violence:

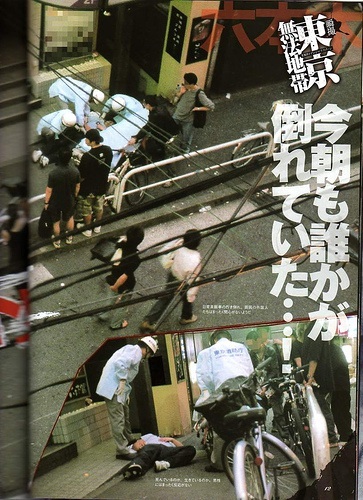

A photo showing a stabbed “exchange student” (pages 4-5) has captions speculating on what might have happened: “Is this a struggle between foreign crime groups?” A person found unconscious on a Roppongi sidewalk, receiving medical attention from officials while gaijin and Japanese rubberneck, is interpreted (page 12) as “the surrounding foreigners look as though they have no concern whatsoever” (shuui no gaikokujin tachi wa mattaku kanshin ga nai you da). Roppongi is explicitly portrayed as “a city without nationality” (mukokuseki toshi) where, as the conjoined article stresses, only the fittest survive.

Nowhere mentioned are the yakuza domestic crime syndicates, with a much longer history of committing the same types of crimes in this area. Since Gaijin Hanzai is about foreign crime, no comparisons are offered with Japanese criminality (the overwhelming majority of all crime in Japan [8]).

The bias is also visual. Photos that show mixed-nationality scenes have the Japanese faces blurred out. The gaijin faces, however, are mostly left intact, regardless of privacy concerns. When asked about this (see below), the editor claimed it necessary for “the illustrative power of the image”, so readers could “recognize [the criminal] as foreign.” This, however, amounts to targeting foreigners because they look foreign, even if they are bystanders in a scene and not the suspected miscreants.

Gaijin Hanzai then gives extensive case studies on foreign criminality, depicting crime as something committed by nationalities, not individuals.

There is an interview (pages 32-33) with an Instructor at Nihon University School of International Relations named Oizumi Youichi. He shares his insights into the general gaijin criminal mind through his studies of criminality in Spain. The article’s point is to demonstrate that the Japanese police and soft Japanese society lack the mettle to deal with more hardened foreign criminals.

Pages 34-37 depict China as a breeding ground for hardened criminality. South Korea is similarly depicted (pages 38-39) but fortified further by hatred for Japan. This is followed by a more sympathetic section about Nikkei Brazilians (pages 40-41), who, given their hardships overseas, would understandably want to re-emigrate back to their homeland; unfortunately, they have been corrupted by foreign habits, including criminality.

This is followed by a write-up on the US military (pages 42-43), whose crimes are “too small” (bag snatching, shoplifting, petty theft, bilking taxi drivers…), yet still cast doubt on their ability to “keep peace in the Far East”.

Pages 44-45 offers a write-up on foreign laborers in general (“now 700,000 people!!”) with some background on their situation. This too focuses more on the social damage they allegedly cause than on their possible benefit to Japan (such as how cheap foreign labor has helped make Toyota the world’s number two automaker [9]).

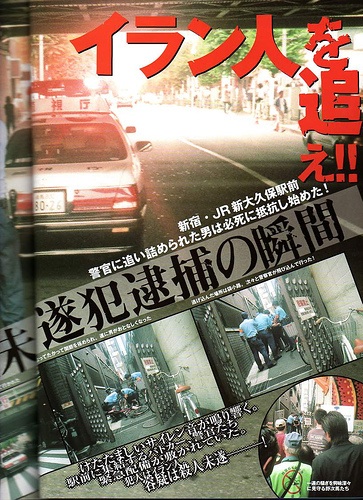

Finally, the NPA (headline: “These are the days which try the strength of the police”, pages 46-47) is selectively quoted to make the case that they are understaffed and need more money. A final page covers the rest of the sundry criminal gaijin: Iranians, Russians, Central and South Americans, Malaysians, and other “global foreign crime gangs”.

“Gaijin Crime” Case Studies

The remainder of this book is devoted to graphic storytelling. The next section (pages 49-59) leads with a Top Ten of Foreign Crime Cases (subtitled in English “ALIEN CRIMINAL WORST 10”). Each gets a full page. The majority are murders. North Korea then gets its due, over six pages, making the case that “FOR THE DPRK, CRIME IS BUSINESS”.

This section finishes with a screed on page 64 on how Japanese criminals may be taking refuge in the cruelty of foreign crime: In recent incidents, cut-up corpses have been disposed of in areas with high foreign populations, allegedly to throw the authorities and the media off the scent. Point: Foreigners are raising the bar.

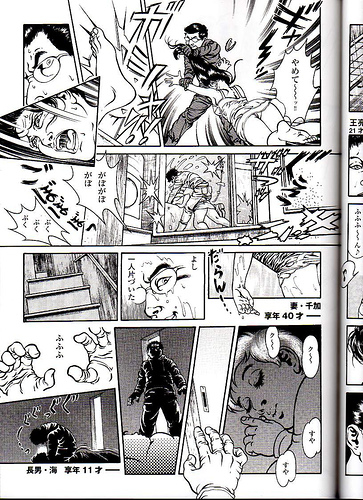

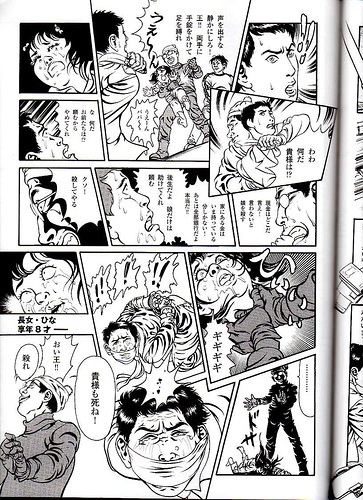

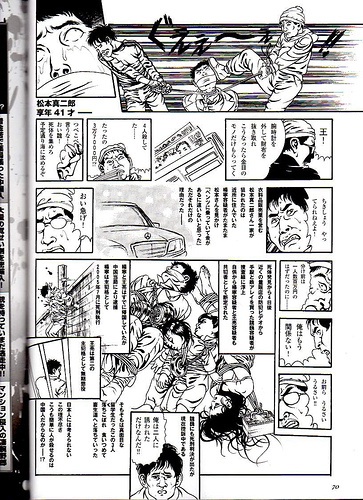

The coup de grace surely belongs to a six-page manga (pages 65 to 70) recreating the 2003 murders of a Fukuoka family by three Chinese “exchange students”. After the Chinese break into the premises, one drowns the wife (who is in a state of undress, drawn titillatingly) in the bath, then smiles (saying, “Good, that’s one out of the way.” (yoshi, hitori katazuita)). Then he strangles her nearby sleeping son.

After they ransack the house for money and unhurriedly vacuum it clean of clues, the husband of the house shows up at the front door. He finds the Chinese threatening to knife his daughter in the genkan unless he reveals where all their money is kept. When he says that all he has is on his person, they strangle her in cold blood before his eyes (dropping her to the floor with a smile).

Then two of them strangle him by pulling a rope between them taut (one putting his foot on the victim’s head for leverage; even though the press has reported he was strangled with a necktie [10]). All this for the 37,000 yen he has in his wallet. The final panel displays the corpses found in a Fukuoka harbor with weights attached. Two of the murderers then escape overseas scot-free.

Looking beyond the shock value and into logic, one wonders how the artists knew what went on in the house during the crime–such as strangulations with a smile? The final caption makes a racist argument: “Nihonjin ni wa kangaerarenai kono rifujin sa. Koumo kantan ni hito ga korosareru no wa chuugokujin da kara na no ka?” “The unreasonable of this is unthinkable to Japanese. Does killing come so easily because these people are Chinese?”

Not really. Japanese people are equally capable of this kind of murder, as history demonstrates. A quick list of famous cases: the Kodaira Yoshio Murders of 1946, the Teigin Poisoning/Bank Robbery of 1948, the Yoshinobu-chan Child Murder of 1963, the Ohkubo Kiyoshi Serial Killings of 1971, the Miyazaki Tsutomu Child Serial Killings of 1988, the Hayashi Masumi Curry Rice Poisonings of 1998, the Mihashi Kaori Wine Bottle Murder in December 2006…

Enough

There is more, but in the interest of brevity [11], let us skip to page 102-103, where the book most clearly crosses the line into “hate speech”. Mentioned are things that are not crimes.

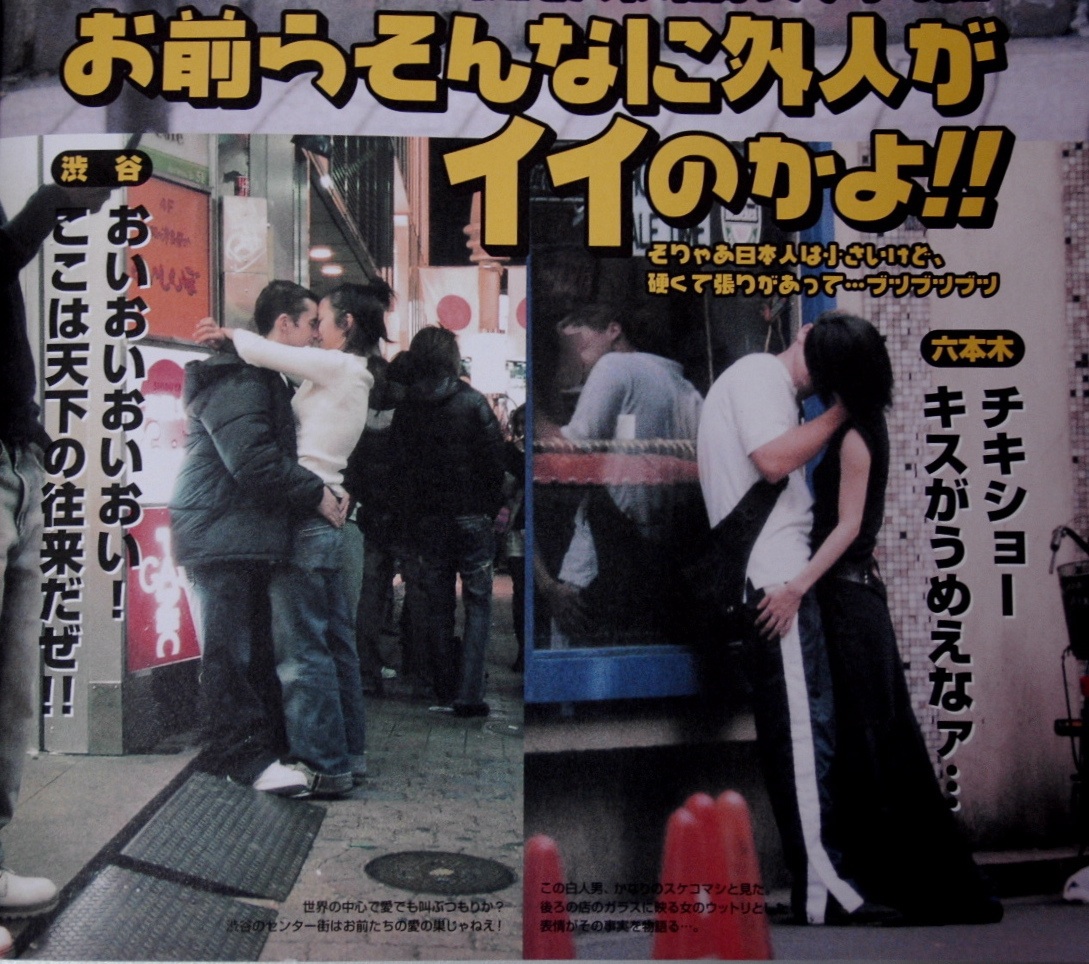

These are the most-cited pages in the book: Photos displaying international couples engaging in public displays of affection and heavy petting on the streets of Roppongi, Shibuya, Shinjuku, and Ikebukuro. The title: “You bitches!! Are gaijin really all that good??” (omaera sonna ni gaijin ga ii no ka yo!!), with a snide comment about the allegedly small size of Japanese genitalia (soryaa nihonjin wa chiisai kedo…).

The captions are vitriolic: “Oi nigger!! Get your hand off that Japanese girl’s ass!! (oi nigaa!! nihon fujoshi no ketsu sawatte n ja nee!!) “Hey hey hey hey! None of that tit rubbing on the street!!” (kora kora kora kora! rojou de nama chichi momi wa nee darou!!). “Hang on! Quit fingering her snatch in the street!” (chotto, chotto chotto! rojou de teman wa yamete kureru?) “This is Japan! Go back to your own countries if you want to do that!” (koko wa nihon nan da yo! temee no kuni ni kaette yari na!)

I am aware this kind of language diverges from the academic tone of Japan Focus. However, the hatefulness is precisely the point. Moreover, as these acts are clearly consensual (as opposed to the chikan mashing that frequently happens on Japanese public transport, to the degree that many Tokyo subway lines now have “Women Only” coaches during morning rush hour), including these photographs in a book on foreign crime is ironic.

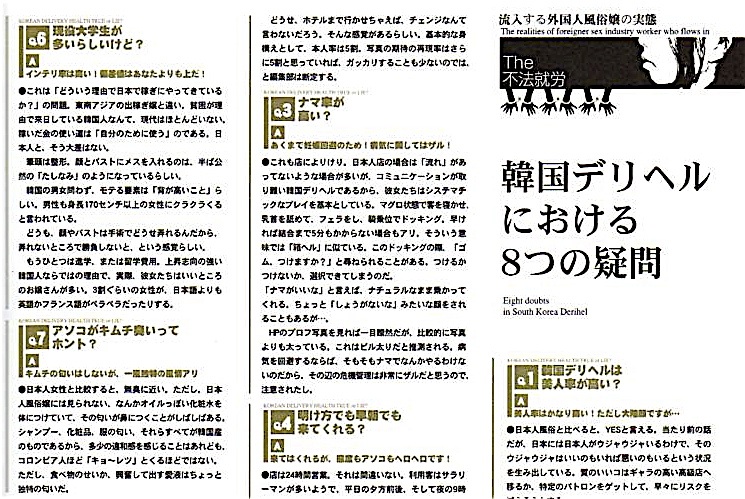

On pages 108 to 112 is a long section on the foreigner sex industry in Japan (focusing on supply, not demand). Gaijin Hanzai provides great detail on how to deal with foreign prostitutes, particularly how to procure them (with a market price listed). Page 112 has a Q&A section on “Delivery Health” Korean professionals, with Question 7 wondering if Korean female pudenda smell of kimchee.

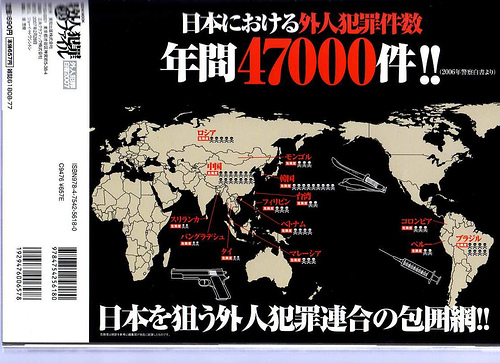

The book closes with a calendar of gaijin crime–187 cases over 2006 organized by month stretched over 12 pages. The back page reads, “Gaijin Crime in Japan–47,000 cases per year”, with a world map (surrounded by guns, knives, and syringes) bearing skull-and-crossbones danger ratings for 14 countries that are “targeting Japan” (nihon o nerau).

The Reaction

On January 31, Gaijin Hanzai went on sale in neighborhood convenience stores and high-volume bookstores nationwide, including Kinokuniya and Amazon Japan. According to The Japan Times (February 23), 30,000 copies were produced, with about half on the shelves of FamilyMart, Japan‘s third-largest convenience store.

The reaction was immediate. On January 31, an Internet blogger named Steve scanned and translated the contentious bits, then notified several Internet mailing lists. Soon dozens of Japan-related blogs and bulletin boards (including Japan Probe, Big Daikon, Trans-Pacific Radio, Mutant Frog, Gaijin Pot, Ikeld, Joi Ito, Ejovi, Fukumimi, Japanjin, Japundit, ESLCafe, and Debito.org.) were buzzing with opinion and outrage. Bloggers sent lists of stores and cellphone videos of where they found the mook, and posters pondered what to do about it.

On February 2, Japan Probe proposed an official boycott of Gaijin Hanzai stockers, particularly FamilyMart. Emails went to their domestic and overseas offices, asking if they would dare sell books like this in other societies. The first newspaper, The Guardian (Manchester), carried a story citing the author: “[Gaijin Hanzai] goes beyond being puerile and into the realm of encouraging hatred of foreigners.”

Within 24 hours, apologies from distributors began coming in. On February 3, FamilyMart’s US subsidiary Famima promised to take the book off the shelves “within seven days” (bloggers pointed out that this was not much of a promise, as a week is probably the mook’s shelf life). Other convenience stores, including Circle K/Sunkus and AM/PM, followed suit. The author went to two stores himself, showed the manager the “nigger” image and “vaginal kimchee” section, and the mook was immediately removed. “We stocked this unaware of the contents,” one apologized.

On the evening of February 3, Debito.org put up a bilingual letter (the pdf version alone was downloaded 1156 times by the end of February) spelling out why the bearer would refuse to shop again at the store unless the mook were immediately returned to the publisher.

By February 5, The Times (London) and Reuters had run stories, as did other media outlets (Australia‘s ABC News and China‘s People’s Daily February 6; Bloomberg, South China Morning Post and IPCJapan (Spain) February 7; finally The Japan Times February 23). The author began including Gaijin Hanzai‘s images in speeches to Japan’s NGOs and human rights groups nationwide, which got visible empathy and outrage (albeit no visible action on the issue). However, with the exception of bilingual bloggers, no Japanese press outlet (including Kyodo News) picked up the story for domestic consumption.

On February 5, FamilyMart, which according to The Japan Times had only sold 1000 mooks, ordered every copy collected and returned to Eichi Publishing. Amazon Japan, however, ignored the boycott, responding with freedom of speech arguments comparing Gaijin Hanzai to Mein Kampf. However, Amazon soon sold out of copies and did not offer any more for sale.

By February 9, Gaijin Hanzai had become a collector’s item. Even Eichi Publishing noted that Gaijin Hanzai was “out of stock”, and Amazon Japan was offering the mook (list price 690 yen) at 20,000 yen (within a week 40,000 yen on eBay). Within a few days, no record would even exist on Eichi’s website that they had ever sold the book. Even with no apparent domestic pressure from Japanese consumers or longstanding domestic human rights groups, victory was total for the Newcomer bloggers.

Eichi’s Defence

On February 16, Gaijin Hanzai’s editor, Mr. Saka Shigeki offered an exceptional and spirited defense of his mook, published both on Japan Today and in Metropolis magazine.

Saka refused to apologize, claiming that he had become a victim of a campaign of harassment, censorship, emotional overreaction, and distortion by an “army of bloggers”. He claimed that these puroshimin (“professional citizens”, best translated as “do-gooders”) had unfairly targeted him even though the only intention was to open a frank discussion on the “taboo” subject of foreign crime. He claimed, “This is not a racist book, because it is based upon established fact,” with “no lies, distortion or racist sentiments.”

He added that translating nigaa as “nigger” was “unfair”, as the term is merely Japanese street slang, with “none of the emotive power in Japanese that the N-word does in English”. Moreover, Japanese have also been victims of racial slurs in the past (citing epithets as far back as World War II), so what was the problem?

He concluded by saying that discussing “the issue of foreign crime in Japan, we will have the opportunity to address our own problems as well… [B]y having a conversation about violent and illegal behavior, we’re really talking about ourselves–not as ‘Japanese’ or ‘foreigners’, but as human beings.”

The overwhelming number of respondents, visible on blogs and the Japan Today website, were not convinced–expressing amazement at Saka’s apparent obliviousness and incoherence. Some pointed out that the book was not talking about “violent and illegal behavior” in general–it was focusing on the foreign element, separating people into “Japanese” and “foreigners” from the very title. The author also posted a paragraph-by-paragraph rebuttal of every argument Saka made in his defense. My conclusion: “If this is the best argument the bigots in Japan can muster, then Japan’s imminent transition to an international, multicultural society will go smoother than expected.”

Why This Case Matters

This is not the first time this has happened. Non-Japanese residents have often decried public sentiments deemed disparaging, unfair, or even racist–sometimes successfully: Anchorman Kume Hiroshi’s “Gaijin should speak broken Japanese” 1996 gaffe on national TV (which ended with Kume apologizing for the comment a decade later [12]); the 2003 “Tamachan” Sealion Residency Certificate Demo; the 2002 NTT DoCoMo “Gaijin Deposit” Boycott (which ended with NTT repealing the tariff by 2006), the Mandom “Rastafarian Monkey” ad campaign, NPA “foreign crime” notices and posters in 2002, anti-discrimination lawsuits such as the Ana Bortz, Steve McGowan, and Otaru Onsen cases, and many others are discussed at the Debito.org website.

Behind all of these movements has been the power of the Internet. Correspondents and advocates were linked worldwide as never before, to inform, network, and campaign effectively enough to be noticed by authorities, major public outlets and opinion makers. Their tactics included letter campaigns, media exposure, public shame, face-to-face negotiations, demonstrations, and humor. It gave non-Japanese (especially the “Newcomer” immigrants, who have anti-defamation leagues nowhere nearly as powerful as the longstanding “Oldcomer” Zainichi organizations) unprecedented power.

What made the Gaijin Hanzai case special, even historical, is that the mook was removed from the shelves without any involvement whatsoever from the domestic media or long-established domestic NGOs. As the author wrote in his rebuttal to Saka:

“In conclusion, the reason why the mook should not go back on the shelves:

“In my view, when one publishes something, there are of course limits to freedom of speech. Although Japanese laws are grey on this, the rules of thumb for most societies are you must not libel individuals with lies, maliciously promote hate and spread innuendo and fear against a people, and not willfully incite people to panic and violence. The classic example is thou must not lie and shout ‘fire’ in a crowded theater. But my general rule is that you must not make the debate arena unconducive to free and calm, reasoned debate.

“Gaijin Hanzai fails the test because it a) willfully spreads hate, fear, and innuendo against a segment of the population, b) fortifies that by lacking any sort of balance in data or presentation, and c) offers sensationalized propaganda in the name of “constructive debate”. Dialog is not promoted by fearmongering.

“Even then, we as demonstrators never asked for the law, such as it is, to get involved. We just notified distributors of the qualms we had with this book, and they agreed that this was inappropriate material for their sales outlets. We backed that up by proposing a boycott, which is our inviolable right (probably the non-Japanese residents’ only inviolable right) to choose where to spend our money as consumers. We proposed no violence. Only the strength of our argument and conviction.”

Gaijin Hanzai editor Saka himself assumed that non-Japanese would either be unable to read the mook in Japanese, or, despite his express desire for free and open debate throughout Japan, would not be included as part of the audience. As he stated in his February 7 interview with ipcdigital.com:

ipcdigital.com: What is your opinion on the reaction of the public about your magazine?

Saka Shigeki: I don’t understand it yet well. There are a lot of questions from foreign press [outlets] as Reuters or Bloomberg. I know there are a lot of complaints. But that depends on how you receive this stuff. In principle it is a magazine written in Japanese and sold in Japan. Then, it’s for Japanese people to read. Besides, in the magazine there are not any discriminatory claims, though I imagine that foreigners who are always discriminated are a little bit more sensitive…

ipcdigital.com: Don’t you think the way the photographs are used is tendentious?

Saka Shigeki: If you read the magazine you will understand it. Maybe foreigners can’t read the articles in there and they only see the pictures of the discriminated. [emphases added]

This blind spot, which appears surprisingly often in the Japanese media, assumes that non-Japanese residents, particularly those typically classified as gaijin (the Newcomers), simply “don’t count”; that they haven’t any real voice in Japanese society, and have little power to stop things they might not like. Or even have the ability to read. This has obviously not been the case, especially since earlier public appeals to shame and logic have enlisted the domestic media in changing the course of many a policy. However, as the Gaijin Hanzai Case demonstrates, the power of non-Japanese as a consumer bloc alone for the first time became a force to be reckoned with.

The Invisible Hand Behind the Mook

One unanswered question remains: Who produced this publication? The “publisher” (hakkousha) listed on the binding is a Mr. “Joey H. Washington”, who does not exist. Despite repeated requests, Saka refuses to reveal his patron.

What is clear is that whoever funded this is rich and powerful. There are no advertisements whatsoever within Gaijin Hanzai, yet, according to a source in the publishing world, it would cost at least US$250,000 to print something of this quality and volume. Moreover, this patron is powerful enough to convince Saka, who was scheduled to appear at a luncheon press conference with the United Nations at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan (FCCJ) on February 26, to cancel his appearance.[13]

Allow me to speculate. I believe the National Police Agency, or some police branch, was behind it. Here are my arguments behind that belief:

First, I mentioned deep pockets; what deeper pockets are there than tax monies (which the NPA, and particularly the National Public Safety Commission (kokka kouan iinkai) with their secret budgets and a clear mandate to monitor foreigner activity [14], have ample access to)?

Another clue is the degree of information and access to the police. No fewer than three articles quote the NPA or ex-police officers, and the last pages have masterful summaries of foreign crimes that would be most easily collated from police databases. Even Saka admitted in his abovementioned ipcdigital.com interview that, “We have spoken with Japanese police in order to write each article. For them this issue is serious and they have provided the data.” [Emphasis added]. It is remarkable that police would cooperate to this degree with Eichi Shuppan, a mid-tier pornography publisher, given the borderline legality and threat to “public morals” (fuuki) the sex trades pose within Japan.

The photos are a giveaway. Either the photographer has the patience of Ansel Adams and the ability to be everywhere at once, or the mook includes camerawork of crime scenes from the police. Police officers feature prominently in several photographs, and given how sensitive Japanese cops are to being photographed (I have received many reports from angry photographers, told by police to delete their photos on site, wondering if the NPA has even the right to demand this in a public place), the photographer must be wearing an invisibility cloak.

He must also own a hang glider, since some of the shots (pages 12-13, 22-23) are “eye in the sky”, at just the right angle to be from police surveillance cameras. These spy cameras, by the way, are proliferating throughout certain regions of Tokyo (such as Roppongi and Kabukicho) precisely because they have a high foreign population.

Most indicative is the location of the photos: The foreign crowd scenes are coincidentally caught in places with those surveillance cameras. For a book cataloging foreign crime throughout Japan (given that many other places, such as towns in Shizuoka and Gifu Prefectures, have higher percentages of non-Japanese residents), there is an odd visual focus on Tokyo. Finally, there is data in this book that only the police or Immigration would have access to, such as the passport photo of a suspect (page 19).

If the police are not financially behind the mook, they are certainly supplying data and analysis. This is unsurprising. As I wrote in Japanese Only (pages 196-209), a sea change in police attitudes towards foreigners occurred after the founding of the “Policy Committee Against Internationalization (kokusaika taisaku iinkai) in May 1999. Based upon the White Paper outlining the goals of this organization, the NPA would see foreigners and the internationalization they would cause as a source of crime, something necessitating public policy.[15]

This policy shift was apparent less than a year later, with Tokyo Governor Ishihara’s famous “Sangokujin Speech” of April 9, 2000. Ishihara called upon the Self-Defense Forces to fill in the gaps in Japan’s police forces in the event of a natural disaster, since foreigners would allegedly riot. Since then, the Tokyo Government (the current vice-governor is a former policeman), the Koizumi Administration, the media, and local police agencies have made concerted efforts to create and disperse public-service information regarding the threat to public safety and stability (such as “infectious diseases and terrorism” [16]) which foreigners allegedly pose [17].

This has reached a degree where criminologists have concluded: “[T]he Japanese public’s fear of crime is not in proportion to the likelihood of being victimized. What is different is the scale of this mismatch. While Japan has one of the lowest victimization rates, the International Crime Victim Surveys indicate that it has among the highest levels of fear of crime…” [18]. The authors go on to say, “[T]he Japanese press… is presenting a partial and inaccurate picture of current crime trends.” Another academic concurs, to say that in media coverage, “crimes by foreigners were 4.87 times more likely to be covered than crimes by Japanese.” [19]

Given that the NPA gives regular biannual reports to the media, apprising them specifically of the rise in foreign crime rates (and decline, although sometimes the Japanese media refuses to report it [20]), the NPA supplying this publisher with information is in this author’s opinion neither unprecedented nor out of character. Not to mention that in this age of terrorism, whipping up public fear has proven a very effective measure for loosening public purse strings [21]. Placed on every convenience store in Japan, Gaijin Hanzai is to the author akin to making a public service announcement.

Conclusion

Gaijin Hanzai qualified in many people’s view as “hate speech”, in that it concertedly and maliciously attempted to encourage fear and loathing of an entire segment of Japan‘s population–the “gaijin”. Not only were they singled out for a negative image campaign, they were not even supposed to be part of the audience. Nobody targeted was supposed to care, or be able to do anything about it.

A significant contrast is a recent case of hate speech in the United States. On February 23, AsianWeek published a column by Kenneth Eng entitled “Why I Hate Blacks“. Within it he made allegations justifying “why we should discriminate against blacks”: their racist attitudes towards Asians, their weak constitution (“the only race that has been enslaved for 300 years”), their lack of intelligence, and their Christianity.

Within days, several ethnic anti-defamation leagues and news media were reporting and demanding apologies and retractions; even Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi issued a public condemnation [22]. Eng lost his job. Civil society kicked into action, debated the issue, and shouted the author down. Hate speech has hardly disappeared in the United States, but egregious cases cannot escape the attention of the media, civil organizations and the state.

In Japan, however, the domestic press ignored and continues to ignore the issues surrounding Gaijin Hanzai. Coincidentally, prominent politicians (including Education Minister Ibuki Bunmei) instead dismissed the notion of focusing on human rights at all as “like eating too much butter, resulting in ‘Human Rights Metabolic Syndrome’” –demonstrating the expressly low regard that even people in policymaking positions have for expanding constitutional protections to Japan’s international residents.

Japan‘s lack of regulations, or a developed civil society capable of dealing with hate speech and defamation of entire segments of society, allows publications like Gaijin Hanzai to appear in bookstores without constraint or even comment. It is not the only Japanese publication of its ilk. One book still in print compares foreign penis sizes, and warns its intended female audience that having relations with foreigners is problematic because “they don’t have money”, “their temperament is too strong”, “they want a lot of sex”, and “there are a lot of junkies” [23]. Other recent manga give reasons for hating Koreans, and depict Chinese as cannibals [24]. These still remain on sale, in the name of freedom of expression. In many other societies signatory to the same treaties as Japan, they probably would not be, or if they were, controversy would likely erupt.

So who fought the good fight this time? Civil society, in the form of “Newcomer” activists in Japan, succeeded in taking Gaijin Hanzai off the market. The so-called gaijin are learning how to fight for their rights. In this case, they did it completely by themselves for the first time in Japanese history–showing that they indeed “do count”.

This article was written for Japan Focus and posted on March 19, 2007.

Update:

According to an April 5, 2007 report from Teikoku Databank, Eichi Shuppan, the publisher of Gaijin Hanzai, has gone bankrupt with outstanding debts of 2.3 billion yen.

Arudou Debito is a naturalized Japanese citizen, activist, and an associate professor at Hokkaido Information University. He is the author of JAPANESE ONLY–The Otaru Hot Springs Case and Racial Discrimination in Japan and co-author of the forthcoming GUIDEBOOK for Newcomers (bilingual, Akashi Shoten Inc. 2007). His website, blog and newsletters may be found here; email at [email protected]. His publications, interviews, and speeches are downloadable here. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted March 19, 2007.

See also a Japan Times article on this controversy : “Family Mart Cans Sales” By Masami Ito, Staff Writer. The Japan Times, Friday Feb.23, 2007.

Endnotes

[1] Gaining currency in Japan‘s human-rights circles are the terms orudocamaa and nyuukamaa. For the purposes of this report, “Newcomers” refer to those who have moved to Japan, the immigrant residents. “Oldcomers” refer to “foreigners” who have been born and raised in Japan but, even after up to five generations, do not have Japanese citizenship: the Zainichi ethnic generational foreigners (Koreans, Chinese, etc.).

[2] Full discussion and archive on the Gaiji Hanzai Case at the Debito.org blog, see here.

[3] Recent UN Human Rights Council discussions wrestling with issues of “hate speech”: A/HRC/2/6 dated 20 September 2006, downloadable from here.

[4] Response to the United Nations’ response to Japan‘s First and Second periodical report to the ICERD Committee, October 2001, available here.

[5] For an example of how Japan‘s libel laws work (or rather, do not), refer to the Arudou vs. Nishimura 2-Channel BBS lawsuit.

[6] More context and comparison of foreign crime with Japanese crime (2004), with breakdown by nationality, see here.

[7] Foreign crime in fact fell in 2006, according to the NPA. See The Japan Times/Kyodo News February 9, 2007.

[8] cf. Footnote 5

[9] See Weekly Diamond, June 5, 2004.

[10] “Family slaying accomplice’s death penalty upheld”. The Japan Times March 9, 2007,

[11] See the pages left out here.

[12] “Newscaster regrets anti-foreigner quip”, IHT/Asahi Dec. 21, 2006.

[13] The author appeared in Saka’s stead. Transcript of the event here.

[14] Arudou, Debito, JAPANESE ONLY, The Otaru Hot Springs Case and Racial Discrimination in Japan. Akashi Shoten Inc. 2006, pages 261-265.

[15]”In our country, one of the most serious topics concerning public order is dealing with foreign crime… In May 1999, to plan the promotion of policies which will tackle crimes connected to foreigners… the National Police Agency has established the kokusai taisaku iinkai… which will undertake suitable policies and laws against foreign crime for provincial police agencies, and strengthen their investigative organs.” NPA White Paper 2002: “The State of Crimes by Foreigners Coming to Japan“, Chapter 2, from Japanese Only page 206-207.

[16] Quote the Embassy of Japan in Washington DC.

[17] There are many websites on this, but a few examples: www.debito.org/opportunism.html, www.debito.org/foreigncrimeputsch.html, and “Time to Come Clean on Foreign Crime Wave“, The Japan Times October 7, 2005.

[18] Thomas Ellis & HAMAI Koichi, “Crime and Punishment in Japan: From Re-integrative Shaming to Popular Punitivism.” on Japan Focus website.

[19] MABUCHI Ryougo of Nara University, as reported in the IHT/Asahi Shinbun December 14-15, 2002.

[20] “Upping the fear factor–There is a disturbing gap between actual crime in Japan and public worry over it.“ The Japan Times February 20, 2007.

[21] Examples of this worldwide are plentiful enough to not need further substantiation, but a good example of this phenomenon in Japan was the “anti-hooligan” policy pushes during the World Cup 2002. See more here.

[22] “Asian Week Suspends Writer Of Racist Column.” NBC TV San Francisco, February 28, 2007.

[23] Joshi Gakusei Raraku Manual. Hikou Mondai Kenkyuukai, December 1995, particularly pages 72-75. ISBN 4887183453. Available at Amazon Japan.

[24] Manga Kenkanryuu. August 2005 (1) and sequel February 2007. Respective ISBNs: 488380478X and 4883805166. Manga Chuugoku Nyuumon: Yakkai na Rinjin no Kenkyuu: AKIYAMA George and OH Fumio. August 2005. ISBN 487031682X. Both available at Amazon Japan.