“Little Citizens” and “Star Pupils”:

Translated and adapted by Adam Lebowitz

Translator’s Introduction: On 17 July, 2006, The Asahi Shinbun began a daily feature entitled Shashin ga Kataru Senso (The war as photos tell it) based on photos taken during World War II by the newspaper’s cameramen. Stored in an

If considered as an editorial statement, the explanation is important because it counters the logic of denial. This is because researchers and politicians who argue against Imperial Army responsibility for atrocities point to lack of material evidence in the form either of official orders or visible proof: nothing is “left behind”. The Asahi’s feature in contrast provides visual evidence that is “left behind” (nokosarete-iru) to illustrate the violence and coerciveness of the wartime regime.

The coercive nature of primary and secondary education during the war was the subject of the 8 July, 2007 edition featuring military boarding middle schools (rikugun yonen gakko). It is not difficult to see how such an issue has current relevance beyond historical debate. Recent Japan Focus articles on changes to Japan’s education curriculum (Japan’s Education Law Reform and the Hearts of Children and Hammering Down the Educational Nail: Abe Revises the Fundamental law of Education) have noted the renewed emphasis on patriotism and “morality”. As the photos and interviews in the As ahi article show, given certain conditions a patriotic education can easily convince children that the only “just death” (isagiyoi-shi) is self-sacrifice for the nation. A.L.

Believing in the Righteousness of a Noble Death

In the 1930’s as the military strengthened its position in the highest echelon of government, children’s lives became more colored by wartime ideology. In 1934 the first directive ordering schools to train students “psychologically and physically” was iss ued. This was followed by the Education Edict of March 1941 that renamed primary schools ko kumin gakko (schools for national citizenry). The goal was to provide primary-level education in the imperial way and to polish and perfect (rensei) the individual’s sense of national duty. Martial arts, formation drills, model recitations, and ritualized displays of respect for the Emperor became part of the regular curriculum. Pre- and primary-school age children were called sho-kokumin (literally “little citizens”).

As

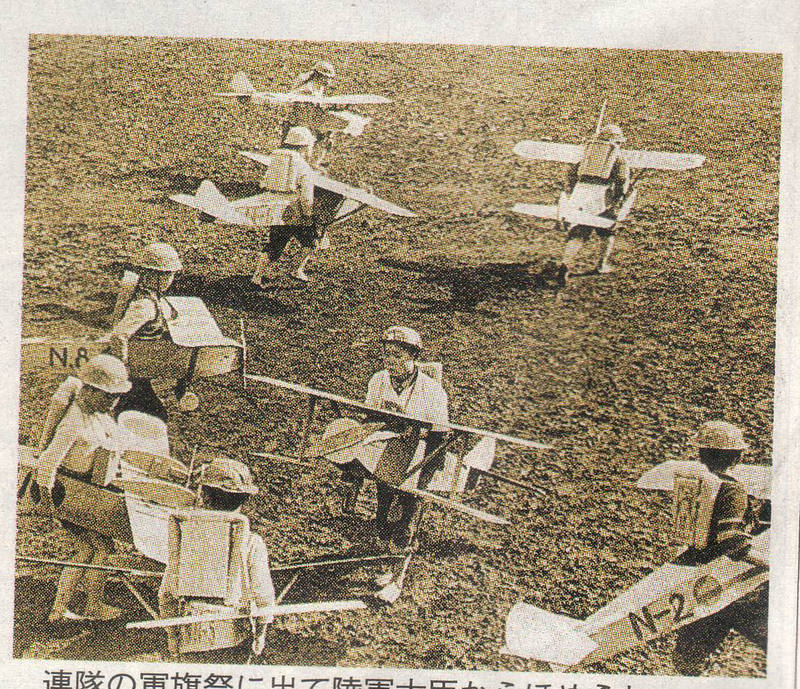

During the war all children devoted their time outside of school to the national

defense by participating in air raid drills and collecting metal. Playtime was senso-gokko, “make-believe warfare”, such as making toy guns or engaging in battles. Children’s magazines dedicated themselves to the promotion of militaristic mentality through articles celebrating the military and pictorials of tanks, battleships, and other weapons. The Asahi Shinbun and the major publishing house Kodansha also p roduced their own weeklies for “little citizens.”

Military Middle Boarding Schools

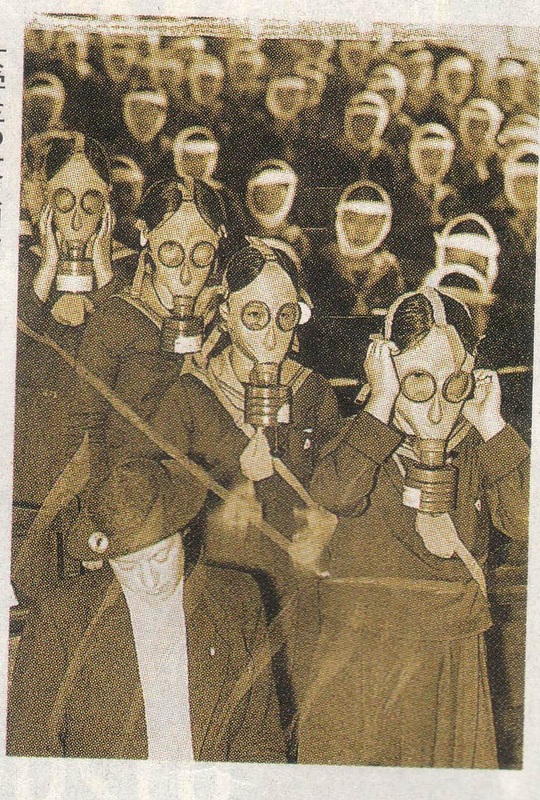

Students at a girls’ middle school practice wearing gas masks, Osaka, September, 1937 |

On April 1, 1940 – “Year 2600” in the imperial reign calendar adopted by the government linking the modern nation of

By the beginning of the twentieth century six primary schools for training officers had been established across

The Asahi Shinbun covered the school twice in the 1940s in articles entitled “Nurturing the Spirit of the Imperial Army” and “Even as they learn history and math, all materials have but one objective.” The three-year course did not differ significantly from the standard jun ior high school education with a special emphasis on “cultivating a warrior spirit.” All students slept in barracks and woke at 6 a.m. to reveille. Then they dressed in uniform, stood in formation, bowed in the direction of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, recited from a military primer, and had their rifles inspected. Students were taught how to handle the katana sword, imperial history, army regulations, military music, and kendo and weapons training.

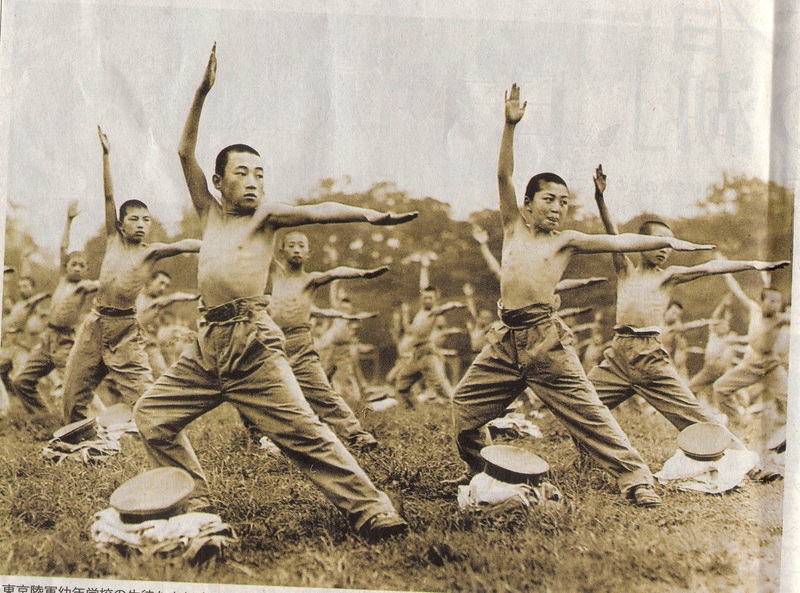

Morning calisthenics at the Tokyo Infantry Middle School, 1943. |

Physical education included mountain climbing, swimming, and formation drilling. Before going to sleep there was silent contemplation. Psychologist and writer Nada Inada (78) was 14 when he entered the

Uwajima Middle School students receive anti-aircraft gun training on the City Hall roof, September 1936. |

A number of A-Class war criminals graduated from these schools including former Prime Minister Tojo Hideki and Army General Itagaki Seishiro. According to

After

Daily Schedule of the

6:00 Reveille, role-call, paying respects to Emperor, calisthenics, washing-up, weapons inspection

6:45 Prayers and breakfast

7:15 Study

7:45 Uniform inspection

8:00 Classes

10:50 Rest, exercise

11:05 Classes

12:10 Lunch, rest, health inspection

13:00 Classes or study

14:05 Training and practice (tutoring, exercise, kendo, military psychology, etc.)

16:00 Extra-curricular activity

16:50 Weapons cleaning, bathing, dinner, one hour of study

19:50 Second hour of study

20:50 Silent contemplation

21:00 Roll call

21:30 Lights out

For additional reports on wartime children, see:

- Owen Griffiths, Militarizing Japan: Patriotism, Profit, and Children’s Print Media, 1894-1925

- Takahashi Akihiro, Ground Zero 1945. A Schoolboy’s Story

Adam Lebowitz teaches at the University of Tsukuba. A Japan Focus associate, he has contributed a chapter in the forthcoming Global Oriental publication The Power of Memory in Modern Japan. His Japanese poetry appears in the literary monthly Shi to Shiso (Poetry and Thought). He wrote this article for Japan Focus.

Posted on October 13, 2007.

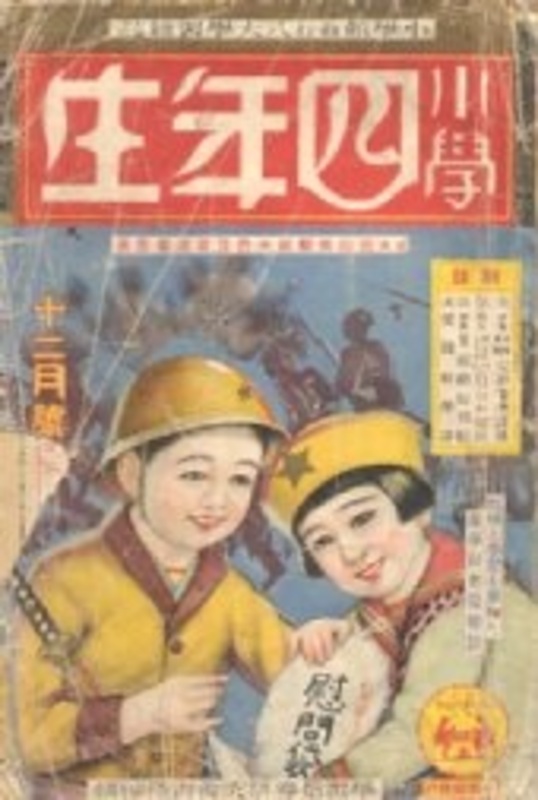

Covers from two wartime children’s magazines showing imonbukuro “care packages” prepared for the troops (note the sword carried by the boy in the lefthand cover). The cover of Kinderbook (right) has the subtitle “Thank you, soldiers.” Kinderbook celebrates its 80th anniversary in 2007, but from 1942-45 it was called “Mikuni no Kodomo” (Children of the Beautiful Country).